Abstract

Background

In the Republic of Congo, with two massive outbreaks of chikungunya observed this decade, little is known about the insecticide resistance profile of the two major arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Here, we established the resistance profile of both species to insecticides and explored the resistance mechanisms to help Congo to better prepare for future outbreaks.

Methods

Immature stages of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus were sampled in May 2017 in eight cities of the Republic of the Congo and reared to adult stage. Larval and adult bioassays, and synergist (piperonyl butoxide [PBO]) assays were carried out according to WHO guidelines. F1534C mutation was genotyped in field collected adults in both species and the polymorphism of the sodium channel gene assessed in Ae. aegypti.

Results

All tested populations were susceptible to temephos after larval bioassays. A high resistance level was observed to 4% DDT in both species countrywide (21.9–88.3% mortality). All but one population (Ae. aegypti from Ngo) exhibited resistance to type I pyrethroid, permethrin, but showed a full susceptibility to type II pyrethroid (deltamethrin) in almost all locations. Resistance was also reported to 1% propoxur in Ae. aegypti likewise in two Ae. albopictus populations (Owando and Ouesso), and the remaining were fully susceptible. All populations of both species were fully susceptible to 1% fenitrothion. A full recovery of susceptibility was observed in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus when pre-exposed to PBO and then to propoxur and permethrin respectively. The F1534C kdr mutation was not detected in either species. The high genetic variability of the portion of sodium channel spanning the F1534C in Ae. aegypti further supported that knockdown resistance probably play no role in the permethrin resistance.

Conclusions

Our study showed that both Aedes species were susceptible to organophosphates (temephos and fenitrothion), while for other insecticide classes tested the profile of resistance vary according to the population origin. These findings could help to implement better and efficient strategies to control these species in the Congo in the advent of future arbovirus outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue virus (DENV), Zika virus (ZIKV), yellow fever virus (YFV) and chikungunya virus (CHIKV) are Aedes-borne viruses of medical concern in tropical and subtropical regions. During the last two decades, diseases caused by these viruses are increasingly reported in several regions of the world including in Central Africa [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] where the epidemics were formerly considered as scarce (apart for YFV). These diseases are transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito belonging to the Aedes genus. Both urban vectors, Aedes aegypti Linnaeus 1762 and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) 1894 are well established in Africa where Ae. aegypti is native [11]. Ae albopictus, which originated from South-East Asia forests, was reported for the first time in Central Africa in the early 2000s in Cameroon [12] and has since progressively colonized almost all countries in the region including the Republic of the Congo where it tends to supplant the resident species Ae. aegypti in sympatric areas [13,14,15,16]. During the chikungunya outbreak reported in the Republic of the Congo in 2011 with more than 11 000 cases, CHIKV was detected in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus [6, 17]. Aedes albopictus was suspected as the main vector during the recent chikungunya outbreak reported in 2019 in the Republic of the Congo [7]. It was demonstrated that both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus from Brazzaville (Congo) are able to transmit YFV [18].

In the absence of effective vaccines (apart for YFV) and specific treatments against these viruses, vector control remains the cornerstone to prevent and control outbreaks. Existing vector control strategies include destruction of breeding sites and insecticide-based interventions. Indeed, the use of larvicides to treat water storage containers such as barrels and space spraying of adulticides in emergency situations can help to reduce the density of Aedes mosquitoes [19, 20]. Unfortunately, the emergence of insecticide resistance significantly hampers the efficacy of insecticides to control pests. Thus, many vector control programmes are facing the challenge from the development of insecticide resistance in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Both major vectors have been found to be resistant to several classes of insecticides in different regions across the world with significant variation according to the population’s origin and the insecticide class including pyrethroids, organophosphates and organochlorines [21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes is primarily associated with two major mechanisms: enhanced expression of detoxification enzymes (metabolic resistance) and insensitivity of target sites (target-site resistance) [28, 29]. Target site resistance is caused by mutations in target genes such as the acetylcholinesterase (Ace-1), the GABA receptor and the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) causing knockdown resistance (kdr). One of the most important target site resistance for mosquitoes is VGSC as it confers resistance to both pyrethroids and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). To date, 11 kdr mutations in VGSC domain I–IV have been identified in Ae. aegypti around the world and the association between F1534C, V1016G, I1011M and V410 L mutations and pyrethroid resistance has been established [27, 30, 31]. In Africa only 1534 and 1016 mutations have been previously reported in Burkina-Faso [31] and Ghana [24] in Ae. aegypti. For Ae. albopictus, four VGSC mutations have been found with only the F1534S variant been shown to be moderately associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids [27]. On the other hand, metabolic resistance through overexpression of detoxification genes is a common resistance mechanism in both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. The three primary enzyme families responsible for insecticide resistance in mosquitoes are the monooxygenases (cytochrome P450s), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and carboxylesterases (COEs) [29, 32]. In Central Africa, data on insecticide resistance in Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus are very scarce apart from a preliminary studies performed in Cameroon [21, 23] and Central African Republic [22]. Unfortunately, no data in this regard is available in the Republic of the Congo although the country has experienced two major chikungunya outbreaks in this decade. To fill this important knowledge gap, we established the insecticide resistance profile of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus from different locations in the country and explored the potential resistance mechanisms involved to prepare the Republic of the Congo to better respond in the advent of future outbreaks.

Methods

Mosquito collection

Immature stages of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus were sampled in May 2017 corresponding to the long rainy season in eight localities of the Republic of the Congo (Fig. 1): Brazzaville (S 4°15′36″ E 15°17′23″), Lefini (S 2°54′58“ E 15°37’56”), Ngo (S 2°29′14“ E 15°45’00”), Gamboma (S 1°52′27“ E 15°52’25”), Owando (S 0°29′42“ E 15°54’41”), Makoua (S 0°00′23“ E 19°37’33”) and Ouesso (N 1°36′35“ E 16°02’58”). Detailed characteristics of each collection site are presented in previous studies [13]. In each location, mosquitoes were collected in peri-urban and downtown at a minimum of 20 containers per site. Larvae/pupae of Aedes mosquitoes were transported to an insectary and pooled together according to the city and maintained until they emerged as adults before morphological identification using a suitable taxonomic key [33]. Adult mosquitoes were pooled according to location and species, and reared in controlled conditions at 28 ± 1 °C under 12 h dark:12 h light cycle and 80 ± 10% relative humidity until G1/G2 generation. Three reference susceptible strains were used as controls: the Ae. aegypti New Orleans strain, Ae. aegypti Benin strain and the Ae. albopictus susceptible strain from the Malaysia Vector Control Research Unit (VCRU).

Insecticides susceptibility tests

Larval bioassays

Larval bioassays were performed according to standard WHO guidelines [34, 35] using F1/F2 larvae. The susceptibility of larvae was evaluated against technical-grade temephos (97.3%; Sigma Aldrich-Pestanal®, Germany). First, stock solutions and serial dilutions were prepared in 95% ethanol and stored at 4 °C. Five doses of concentration ranging from 0.0025 to 0.006 mg/L have been used for the assay. Eighty to 100 larvae per concentration (with three to four replicates, depending on the sample and the number of larvae available) were tested. Third late instar larvae of each species were placed in plastic cups containing 99 ml of tap water, and 1 ml of insecticide solution at the required concentration was added. Control groups were run systematically with larvae exposed to 1 ml of ethanol. No food was provided to larvae during the bioassays, which were run at 28 ± 2 °C and 80 ± 10% relative humidity. Mortality was scored after 24 h of exposure to the insecticide. Mortality rates were corrected with Abbott’s formula [36] when the mortality of controls was > 5%.

All data were analysed with Win DL v. 2.0 software [37]. Lethal concentrations (LC50 and LC95) were estimated with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Resistance ratios (RR50 and RR95) were calculated by comparing the LC50 and LC95 for each species with those of susceptible strain, as RR50 = LC50 of studied population/LC50 susceptible strain and RR95 = LC95 of studied population/LC95 reference strain. A mosquito population was considered susceptible when RR50 was less than 2, potentially resistant when RR50 was between 2 and 5, and resistant when RR50 was over 5 [23].

Adult bioassays

Insecticide susceptibility bioassays were performed with 3 to 5 day old unfed Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes according to the standard WHO guideline [35]. Six Ae. albopictus populations and two Ae. aegypti populations were used for the assays. Four replicates of 20 to 25 mosquitoes from G1/G2 generation per tubes were tested to five insecticides: 4% DDT (organochlorine), 1% propoxur (carbamate), 1% fenitrothion (organophosphate), 0.05% deltamethrin and 0.025% permethrin (pyrethroids). Insecticide-impregnated papers were supplied by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Mortality was recorded 24 h later and mosquitoes alive and dead after exposure 24 h were stored in RNAlater (Sigma, Netherland) and silica gel respectively.

Synergist assay

In order to investigate the potential role of oxidases in the metabolic resistance mechanism, synergist assay was performed when the number of mosquitoes permitted using 4% piperonyl butoxide (PBO). Three–five day-old adults were pre-exposed for 1 h to PBO-impregnated papers and after that immediately exposed to the selected insecticide. Mortality was scored 24 h later and compared to the results obtained with each insecticide without synergist according to the WHO standards [35].

Investigating of F1534C mutation using allele specific PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from around 30 individuals (G0) of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus per populations using the Livak protocol ([38]. These DNA were used to genotype the F1534C mutation which was found mostly widespread across the world in Ae. aegypti and associated with type I pyrethroid resistance and DDT resistance. Experiments were performed using allele specific (AS) PCR assays previously described [39]. As the genomic sequence of the sodium channel gene spanning the IIIS6 segment between both species is highly conserved, we employed the same AS-PCR previously designed for the F1534C variation in Ae. aegypti [39] also for Ae. albopictus. Each PCR was performed using a Gene Touch thermal cycler (Bulldog Bio, Portsmouth, USA) in a 15 μl volume containing: 1 μl of DNA sample, 0.4 units of Kapa Taq DNA polymerase, 0.12 μl of 25 mmol/L dNTPs (0.2 mmol/L), 0.75 μl of 25 mmol/L MgCl2 (1.5 mmol/L), 1.5 μl of 10 × PCR buffer (1×), 0.51 μl of each primers (0.34 mmol/L). The amplification consisted of 95 °C for a 5 min heat activation step, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C (60 °C for Ae. albopictus) for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s with a 10 min final extension step at 72 °C. PCR products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis in Tris-Acid-EDTA buffer (TAE). The 3% gel was prepared with Midori green, staining dye, and visualized with the aid of UV light.

Polymorphism of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) gene in Ae. aegypti

To assess the polymorphism of the VGSC gene and detect possible signatures of selection, a fragment of this gene spanning the F1534C mutation (a part of segment 6 of Domain III) was amplified and sequenced in 30 G0 field collected mosquitoes from three locations in the Republic of the Congo. PCR reactions were carried out using 10 pmol of each primer (aegSCF7: GAGAACTCGCCGATGAACTT and aegSCR7: GACGACGAAATCGAACAGGT) and 20 ng of genomic DNA as template in 15 μl reactions containing 1 × Kapa Taq buffer, 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 U Kapa Taq (Kapa biosystems). The cycle conditions were 95 °C for 5 min and 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. The samples were purified using Exo-SAP (New England Biolab, UK) protocol according to manufacturer recommendations and sent for sequencing in Centre for Genomic Research at the University of Liverpool. The sequences were visualized and corrected when necessary using BioEdit software version 7.0.5.3 and aligned using ClustalW [40]. DnaSP v5.10 [41] was used to define the haplotype phase and the genetic parameters including number of haplotypes (h), the number of polymorphism sites (S), haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π). The statistical tests of Tajima [42], Fu and Li [43] were estimated with DnaSP in order to establish non-neutral evolution and deviation from mutation-drift equilibrium. A haplotype network was built using the TCS program [44] to further assess the potential connection between haplotypes. A maximum likelihood tree of the sequences obtained and reference sequences from Brazil and Thailand was constructed using MEGA 7.0 [45].

Results

Larval bioassay

Due to the limited number of larvae available, larval bioassays were performed for two Ae. aegypti populations from Ngo and Brazzaville, and one Ae. albopictus population from Brazzaville. Analysis revealed that for both Aedes species and populations tested, RR50 and RR95 were less than 2 suggesting that Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus of these locations are susceptible to temephos (Table 1).

Insecticide resistance profile in adults Aedes

Assays performed with laboratory susceptible strains confirmed that Ae. albopictus (VCRU), Ae. aegypti (New Orleans) and Ae. aegypti (Benin) were totally susceptible to insecticides tested except to DDT for which 80.68% (VCRU strain) and 98.75% (New Orleans strain) mortality rates were found, respectively. The mortality rate in controls was less than 5%.

Resistance pattern for Ae. aegypti

Two Ae. aegypti populations from Brazzaville (the major city of the country) and Ngo were tested for resistance to five insecticides (Fig. 2). In Brazzaville population, resistance was observed against the organochlorine DDT with a low mortality rate of 41.2%. Resistance was also observed against pyrethroids, notably permethrin (type I) with 71.0% mortality registered whereas mortality was higher (95.3%) for deltamethrin (Type II). Noticeably, this Ae. aegypti population of Brazzaville is resistant to carbamates with 69.0% mortality for propoxur. However, full susceptibility to the organophosphate fenitrothion was reported in this population in line with the susceptibility observed at the larval stage against the other organophosphate, temephos. The other population from Ngo displayed a moderate resistance level to DDT (88.3%) and a probable resistance to propoxur (91.0%). In contrast to Brazzaville, the Ngo population was fully susceptible to both types of pyrethroids highlighting a variation of susceptibility profile of Ae. aegypti across Congo. It also exhibited a full susceptibility toward the organophosphate fenitrothion (Additional file 1).

Resistance pattern for Ae. albopictus

For Ae. albopictus, six populations were analysed: Brazzaville, Lefini, Ouesso, Gamboma, Makoua and Owando (Fig. 3). Analysis revealed that all the populations tested were resistant to DDT with the mortality rate ranging from 21.9% in Owando to 88.3% in Gamboma. A similar pattern was observed for type I pyrethroid permethrin with mortality rates varying from 40.5% in Owando population to 92.8% in Ouesso. However, for the type II pyrethroid deltamethrin, a probable resistance was reported in Lefini with a mortality rate of 94.4% whereas the other five populations were found susceptible with mortality rates ranging from 98.0% (Makoua, Gamboma and Owando) to 100.0% (Brazzaville and Ouesso). A moderate resistance was detected against the carbamate propoxur in Owando (90.0% mortality) and Ouesso (95.5%) whereas the remaining populations were fully susceptible. As for Ae. aegypti populations, a full susceptibility to the organophosphate fenitrothion was reported in all populations (Additional file 1).

Mortality rates of adult Aedes albopictus from the Republic of the Congo 24 h after exposure to insecticides alone or with 1 h pre-exposure to synergist. a, Brazzaville; b, Makoua; c, Ouesso; d, Leffini; e, Owando; f, Gamboma. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. DDT, Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. PBO, Piperonyl butoxide

Synergist assay with PBO

Results from the synergist assay in the Ae. albopictus population from Brazzaville resistant to permethrin showed a full recovery of susceptibility after PBO pre-exposure (81.5 ± 3.3% mortality without PBO pre-exposure vs 100 ± 0.0% mortality after PBO pre-exposure, P < 0.001) suggesting that cytochrome P450 enzymes play a major role in permethrin resistance in this population.

Similar analysis for the Ae. aegypti population from Brazzaville showed a full recovery of susceptibility after PBO pre-exposure for the propoxur (69.0 ± 6.1% mortality without pre-exposure versus 100 ± 0.0% mortality after PBO pre-exposure, P < 0.001) suggesting that cytochrome P450 enzymes also play a major role in carbamate (propoxur) resistance in this population (Fig. 3).

F1534 genotyping

After genotyping 64 specimens of Ae. aegypti from three locations and 136 specimens of Ae. albopictus from six locations no resistant individual was detected in both species with 100% homozygote F1534 mosquitoes detected.

Genetic diversity of VGSC gene in Ae. aegypti

Twenty seven field collected Ae. aegypti from three locations were successfully sequenced for an 198 bp fragment of the VGSC gene spanning the codon 1534. Analysis confirmed the absence of F1534 mutation. Overall, a high genetic diversity is observed for this fragment with 10 polymorphic sites, 12 haplotypes, eight synonymous and two non-synonymous mutations associated with a high haplotype diversity (0.823) and relatively low nucleotide diversity (0.008) (Table 2). This high diversity is also supported by the pattern of TCS haplotype network with haplotypes separated with several mutational steps suggesting a lack of selection in this locus although three haplotypes are predominant. The predominant haplotype H4 is found in all three populations (Fig. 4a). A maximum likelihood (ML) tree of the sequences analysed confirms a high diversity with the potential three clusters (Fig. 4b). Overall, all the statistics estimated were negatives (D = − 0.79, Fs = − 3.82, and F* = − 0.19), but not statistically significant (Table 2). Negative values for these indices indicate an excess of rare polymorphisms in a population and suggest either population expansion or background selection [43].

Discussion

This study investigated for the first time the insecticide profile of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus in the Republic of the Congo and explored the resistance mechanism involved. Analysis of larval bioassays revealed that all Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus samples tested were susceptible to temephos. This result is consistent with the previous result obtained in Central Africa notably in Cameroon [23], Gabon [23] and Central African Republic [22]. Nonetheless, the resistance to this compound has been reported in several countries such as in Brazil [46, 47], Malaysia [48], Thailand [49] and Carpe Verde [50] for Ae. aegypti and in Greece [51], Malaysia [48] and Thailand [49] for Ae. albopictus. Selection of the resistance results from extensive and long-term use of the product incriminated, meanwhile in our knowledge, temephos had never been used in vector control programs in Central Africa which probably explains the full susceptibility reported in both species.

Both adult populations of Ae. aegypti tested were resistant to DDT. A similar pattern of resistance to DDT was shown in Ae. albopictus populations. A decreasing susceptibility of the Ae. aegypti population from Brazzaville towards DDT was already mentioned in 1970s [52], suggesting that this resistance may have resulted from a continuing selection pressure on Aedes populations as suggested previously [22]. DDT resistance has repeatedly been reported in Ae. aegypti [21, 22, 48, 53] and Ae. albopictus [21, 54,55,56]. Both species exhibited a significant level of resistance against the type I pyrethroid permethrin, loss of susceptibility to this insecticide was previously reported in neighbouring countries such as Cameroon [21]. However, the fact that one population of Ae. aegypti remains fully susceptible suggests that pyrethroid resistance has not yet spread nation-wide in the Republic of the Congo. On the other hand, for the type II pyrethroid, deltamethrin, no resistant population was found despite a reduced susceptibility reported in some populations in both species. The striking difference of the resistance pattern in both pyrethroids tested could be due to the fact diagnostic dose used for deltamethrin 0.05% is higher than 0.03% recommended for Aedes [35]. The reduced susceptibility to deltamethrin and resistance to permethrin observed in both species may poses a serious threat for vector control programmes, because pyrethroids are mainly recommended for the control of adult Aedes mosquitoes [57, 58]. A loss of susceptibility was reported also to propoxur with moderate level of resistance in Ae. aegypti population from Brazzaville. Similar patterns of insecticide resistance profile found in this study were reported in several countries in Africa such as Burkina-Faso [59], Central African Republic [22], and Cameroon [21]. The source of selection driving the observed resistance to DDT and permethrin as well as the reduced susceptibility to deltamethrin and propoxur in the Republic of the Congo as in other central African countries remains unclear notably as the use of insecticides against Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus is limited in the region [21, 23]. As suggested previously [21, 22], domestic used of insecticides through the indoor spraying and impregnating bed nets, and agriculture use could be the main source of resistance selection in Aedes vectors in Central Africa. The higher resistance level to DDT observed in Ae. aegypti in the Republic of the Congo would be probably a consequence of the intense DDT spraying in the 1950s and 1960s as part of the malaria elimination campaign as suggested previously [21]. Meanwhile, for Ae. albopictus which was first reported in the Republic of the Congo in 2011 during the chikungunya outbreak in Brazzaville [6], we cannot exclude the possibility that the invading populations possessed the resistance background, as suggested previously [22, 23].

A full recovery of susceptibility to permethrin and propoxur was reported in Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti from Brazzaville respectively after pre-exposure to PBO synergist. This result indicates that the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases are playing the main role in the observed resistance which is consistent with previous data from the sub-region [21, 22]. None of the specimens of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus genotyped possesses the 1534C allele suggesting this mutation is not currently involved in pyrethroid resistance in populations of both species in Congo. Nevertheless, this mutation known as most widely distributed in Aedes aegypti [27] has been detected in sample from West Africa in Ghana [24] and Burkina-Faso [59]. This mutation has also been detected in Ae. albopictus from several countries outside Africa like Brazil, India, Greece, Singapore and China [60]. The high genetic diversity of the VGSC portion spanning codon 1534 further supports the absence of kdr mutation in Ae. Aegypti in Congo as shown by the ML phylogenetic tree and TCS haplotype network. This is similar to the situation where kdr in absent as in Ae. albopictus population from Malaysia [48] or the malaria vector Anopheles funestus [61, 62]. It will be interesting to extend this work in other locations throughout the country, genotype other mutations such as 1016 and 410 which have been found implicated in kdr resistance in Ae. aegypti [27, 30, 31] and investigate the genes involved in metabolic resistance in both Aedes species.

Conclusions

Our study showed that both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus species were susceptible to organophosphates (temephos and fenitrothion), while for other insecticide classes tested the profile of resistance vary according to the population sampled. This first countrywide resistance profile to main insecticide classes in both Aedes vectors in the Republic of Congo should enable this country to quickly implement insecticide-based control interventions in the event of future outbreaks. The full susceptibility of both species to organophosphates at both larval and adult stages makes this insecticide class very suitable for control nation-wide.

Availability of data and materials

DNA sequences reported in this paper were deposited at GenBank (accession number MN823932-MN823943).

Abbreviations

- AS:

-

Allele specific

- DDT:

-

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic

- kdr:

-

Knockdown resistance

- LC:

-

Lethal concentration

- PBO:

-

Piperonyl butoxide

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RR:

-

Resistance ratio

- VCRU:

-

Vector control research unit

- VGSC :

-

Voltage-gated sodium channel

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Leroy EM, Nkoghe D, Ollomo B, Nze-Nkogue C, Becquart P, Grard G, et al. Concurrent chikungunya and dengue virus infections during simultaneous outbreaks, Gabon, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(4):591–3.

Grard G, Caron M, Mombo IM, Nkoghe D, Mboui Ondo S, Jiolle D, et al. Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa)-2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(2):e2681.

Peyrefitte CN, Rousset D, Pastorino BA, Pouillot R, Bessaud M, Tock F, et al. Chikungunya virus, Cameroon, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(5):768–71.

Peyrefitte CN, Bessaud M, Pastorino BA, Gravier P, Plumet S, Merle OL, et al. Circulation of Chikungunya virus in Gabon, 2006-2007. J Med Virol. 2008;80(3):430–3.

Pastorino B, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Bessaud M, Tock F, Tolou H, Durand JP, Peyrefitte CN, et al. Epidemic resurgence of chikungunya virus in democratic Republic of the Congo: identification of a new central African strain. J Med Virol. 2004;74(2):277–82.

Moyen N, Thiberville SD, Pastorino B, Nougairede A, Thirion L, Mombouli JV, et al. First reported chikungunya fever outbreak in the republic of Congo, 2011. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115938.

Fritz M, Taty Taty R, Portella C, Guimbi C, Mankou M, Leroy EM, Becquart P, et al. Re-emergence of chikungunya in the Republic of the Congo in 2019 associated with a possible vector-host switch. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;84:99–101.

Nemg Simo FB, Sado Yousseu FB, Evouna Mbarga A, Bigna JJ, Melong A, Ntoude A, et al. Investigation of an outbreak of dengue virus serotype 1 in a rural area of Kribi, South Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Intervirology. 2018;61(6):265–71.

Yousseu FBS, Nemg FBS, Ngouanet SA, Mekanda FMO, Demanou M. Detection and serotyping of dengue viruses in febrile patients consulting at the new-Bell District Hospital in Douala, Cameroon. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204143.

Kraemer MUG, Faria NR, Reiner RC Jr, Golding N, Nikolay B, Stasse S, et al. Spread of yellow fever virus outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2015-16: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(3):330–8.

Mattingly PF. Genetical aspects of the Aedes aegypti problem. I. Taxonom: and bionomics. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1957;51(4):392–408.

Fontenille D, Toto JC. Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse), a potential new dengue vector in southern Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(6):1066–7.

Kamgang B, Wilson-Bahun TA, Irving H, Kusimo MO, Lenga A, Wondji CS. Geographical distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) and genetic diversity of invading population of Ae. albopictus in the Republic of the Congo. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:79.

Tedjou AN, Kamgang B, Yougang AP, Njiokou F, Wondji CS. Update on the geographical distribution and prevalence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae), two major arbovirus vectors in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(3):e0007137.

Kamgang B, Ngoagouni C, Manirakiza A, Nakoune E, Paupy C, Kazanji M. Temporal patterns of abundance of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) and mitochondrial DNA analysis of Ae. albopictus in the Central African Republic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(12):e2590.

Ngoagouni C, Kamgang B, Nakoune E, Paupy C, Kazanji M. Invasion of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) into Central Africa: what consequences for emerging diseases? Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:191.

Mombouli JV, Bitsindou P, Elion DO, Grolla A, Feldmann H, Niama FR, et al. Chikungunya virus infection, Brazzaville, republic of Congo, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(9):1542–3.

Kamgang B, Vazeille M, Yougang AP, Tedjou AN, Wilson-Bahun TA, Mousson L, et al. Potential of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit yellow fever virus in urban areas in Central Africa. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):1636–41.

WHO. Vector control operations framework for Zika virus. Geneva: World Health Organization, WHO/ZIKV/VC/16.4; 2016.

Kroeger A, Lenhart A, Ochoa M, Villegas E, Levy M, Alexander N, McCall PJ. Effective control of dengue vectors with curtains and water container covers treated with insecticide in Mexico and Venezuela: cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7552):1247–52.

Kamgang B, Yougang AP, Tchoupo M, Riveron JM, Wondji C. Temporal distribution and insecticide resistance profile of two major arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Yaounde, the capital city of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10(1):469.

Ngoagouni C, Kamgang B, Brengues C, Yahouedo G, Paupy C, Nakoune E, et al. Susceptibility profile and metabolic mechanisms involved in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus resistant to DDT and deltamethrin in the Central African Republic. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):599.

Kamgang B, Marcombe S, Chandre F, Nchoutpouen E, Nwane P, Etang J, et al. Insecticide susceptibility of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Central Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:79.

Kawada H, Higa Y, Futami K, Muranami Y, Kawashima E, Osei JH, et al. Discovery of point mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel from African Aedes aegypti populations: potential phylogenetic reasons for gene introgression. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(6):e0004780.

Bharati M, Rai P, Saha D. Insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus Skuse from sub-Himalayan districts of West Bengal. India Acta Trop. 2019;192:104–11.

Bharati M, Saha D. Multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms in primary dengue vector, Aedes aegypti (Linn.) from dengue endemic districts of sub-Himalayan West Bengal, India. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203207.

Moyes CL, Vontas J, Martins AJ, Ng LC, Koou SY, Dusfour I, et al. Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(7):e0005625.

David JP, Ismail HM, Chandor-Proust A, Paine MJ. Role of cytochrome P450s in insecticide resistance: impact on the control of mosquito-borne diseases and use of insecticides on earth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1612):20120429.

Hemingway J, Hawkes NJ, McCarroll L, Ranson H. The molecular basis of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34(7):653–65.

Haddi K, Tome HVV, Du Y, Valbon WR, Nomura Y, Martins GF, et al. Detection of a new pyrethroid resistance mutation (V410L) in the sodium channel of Aedes aegypti: a potential challenge for mosquito control. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46549.

Sombie A, Saiki E, Yameogo F, Sakurai T, Shirozu T, Fukumoto S, et al. High frequencies of F1534C and V1016I kdr mutations and association with pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti from Somgande (Ouagadougou), Burkina Faso. Trop Med Health. 2019;47:2.

Perry T, Batterham P, Daborn PJ. The biology of insecticidal activity and resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41(7):411–22.

Jupp PG. Mosquitoes of southern Africa. Culicinae and Toxorhynchitinae. Hartebeespoort, South Africa: Ekogilde; 1996.

WHO. Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. Document WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/13. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

WHO. Monitoring and managing insecticide resistance in Aedes mosquito populations. Geneva: World Health Organization, WHO/ZIKV/VC/16.1; 2016.

Abott WS. A simple method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol. 1925;18:265–7.

Giner M, Vassal C, Kouaik Z, Chiroleu F, Vassal JM. Win DL version 2.0. (Paris: CIRAD-CA, U.R.B.I/M.A.B.I.S); 1999.

Livak KJ. Organization and mapping of a sequence on the Drosophila melanogaster X and Y chromosomes that is transcribed during spermatogenesis. Genetics. 1984;107(4):611–34.

Harris AF, Rajatileka S, Ranson H. Pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti from grand Cayman. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2):277–84.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–80.

Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–2.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123(3):585–95.

Fu YX, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133(3):693–709.

Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol Ecol. 2000;9(10):1657–9.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9.

Valle D, Bellinato DF, Viana-Medeiros PF, Lima JBP, Martins Junior AJ. Resistance to temephos and deltamethrin in Aedes aegypti from Brazil between 1985 and 2017. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2019;114:e180544.

Macoris Mde L, Andrighetti MT, Takaku L, Glasser CM, Garbeloto VC, Bracco JE. Resistance of Aedes aegypti from the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, to organophosphates insecticides. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98(5):703–8.

Ishak IH, Jaal Z, Ranson H, Wondji CS. Contrasting patterns of insecticide resistance and knockdown resistance (kdr) in the dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:181.

Ponlawat A, Scott JG, Harrington LC. Insecticide susceptibility of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus across Thailand. J Med Entomol. 2005;42(5):821–5.

Rocha HD, Paiva MH, Silva NM, de Araujo AP, Camacho Ddos R, Moura AJ, et al. Susceptibility profile of Aedes aegypti from Santiago Island, Cabo Verde, to insecticides. Acta Trop. 2015;152:66–73.

Grigoraki L, Lagnel J, Kioulos I, Kampouraki A, Morou E, Labbe P, et al. Transcriptome profiling and genetic study reveal amplified carboxylesterase genes implicated in temephos resistance, in the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(5):e0003771.

Mouchet J, Cordellier R, Germain M, Carnevale P, Barathe J, Sannier C. Résistance aux insecticides D'aedes aegypti et Culex pipiens fatigans en Afrique Centrale. WHO/VBC/72/381, 12P. 1972.

Ayorinde A, Oboh B, Oduola A, Otubanjo O. The insecticide susceptibility status of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in farm and nonfarm sites of Lagos state, Nigeria. J Insect Sci. 2015;15:75.

Vontas J, Kioulos E, Pavlidi N, Morou E. Della Torre a, Ranson H. insecticide resistance in the major dengue vectors Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2012;104:126–31.

Marcombe S, Farajollahi A, Healy SP, Clark GG, Fonseca DM. Insecticide resistance status of United States populations of Aedes albopictus and mechanisms involved. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101992.

Demok S, Endersby-Harshman N, Vinit R, Timinao L, Robinson LJ, Susapu M, et al. Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):333.

Jirakanjanakit N, Rongnoparut P, Saengtharatip S, Chareonviriyaphap T, Duchon S, Bellec C, et al. Insecticide susceptible/resistance status in Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti and Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand during 2003-2005. J Econ Entomol. 2007;100(2):545–50.

Macoris M, Andrighella M, Wanderley D, Ribolla P. Impact of insecticide resistance on the field control of Aedes aegypti in the state of Sao Paulo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:573–8.

Badolo A, Sombie A, Pignatelli PM, Sanon A, Yameogo F, Wangrawa DW, et al. Insecticide resistance levels and mechanisms in Aedes aegypti populations in and around Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(5):e0007439.

Auteri M, La Russa F, Blanda V, Torina A. Insecticide resistance associated with kdr mutations in Aedes albopictus: an update on worldwide evidences. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3098575.

Irving H, Wondji CS. Investigating knockdown resistance (kdr) mechanism against pyrethroids/DDT in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Africa. BMC Genet. 2017;18(1):76.

Menze BD, Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Irving H, Antonio-Nkondjio C, Awono-Ambene PH, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus from northern Cameroon is mediated by metabolic resistance alongside potential target site insensitivity mutations. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0163261.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people living around all the sampling sites and the garage owners for their cooperation during the field investigations.

Funding

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust Training Fellowship in Public Health and Tropical Medicine (204862/Z/16/Z) awarded to BK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK and CSW conceived and designed the experiments. BK, TAW-B and CSW participated in mosquito collections. APY and TAW-B performed the bioassays. APY, TAW-B and BK carried out the data analyses. TAW-B and BK conducted the molecular analyses. BK, TAW-B and CSW wrote the paper. All authors read and approved final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary information

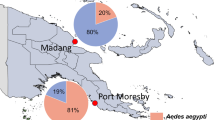

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Map of the Republic of Congo showing the resistance status of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus to insecticide. a, Aedes albopictus; b, Ae. aegypti.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamgang, B., Wilson-Bahun, T.A., Yougang, A.P. et al. Contrasting resistance patterns to type I and II pyrethroids in two major arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in the Republic of the Congo, Central Africa. Infect Dis Poverty 9, 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-0637-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-0637-2