Abstract

With the emergence of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 since December 2019, more than 65 million cases have been reported worldwide. This virus has shown high infectivity and severe symptoms in some cases, leading to over 1.5 million deaths globally. Despite the collaborative and concerted research efforts that have been made, no effective medication for COVID-19 (coronavirus disease-2019) is currently available. SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as an initial mediator for viral attachment and host cell invasion. ACE2 is widely distributed in the human tissues including the cell surface of lung cells which represent the primary site of the infection. Inhibiting or reducing cell surface availability of ACE2 represents a promising therapy for tackling COVID-19. In this context, most ACE2–based therapeutic strategies have aimed to tackle the virus through the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or neutralizing the virus by exogenous administration of ACE2, which does not directly aim to reduce its membrane availability. However, through this review, we present a different perspective focusing on the subcellular localization and trafficking of ACE2. Membrane targeting of ACE2, and shedding and cellular trafficking pathways including the internalization are not well elucidated in literature. Therefore, we hereby present an overview of the fate of newly synthesized ACE2, its post translational modifications, and what is known of its trafficking pathways. In addition, we highlight the possibility that some of the identified ACE2 missense variants might affect its trafficking efficiency and localization and hence may explain some of the observed variable severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Moreover, an extensive understanding of these processes is necessarily required to evaluate the potential use of ACE2 as a credible therapeutic target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following the discovery of renin- and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [1, 2], the understanding of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been greatly improved by the uncovering of associated receptors, enzymes, and protein complexes. Twenty years ago, in an approach of searching for human ACE homolog, two independent groups have identified angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) that shares a common ancestor with ACE, with 42% sequence identity [3, 4]. ACE2 expression disruption studies have identified ACE2 as an important regulator of the blood pressure and cardiovascular functions through its role in the renin-angiotensin system that counteracts ACE functions [5].

With the emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), significant attention has been given to ACE2 due to its involvement as the host’s cellular receptor that mediates the initiation of the viral infection. Consequently, since 2002, approximately 4000 ACE2–related articles have been published where the majority corresponds to 2020 as revealed by a PubMed database search. In 2019, a novel coronavirus has emerged, known as SARS-CoV-2, causing the new coronavirus disease 2019 (termed COVID-19) and leading to unprecedented economic and health burden world-wide. Similar to its predecessor SARS-CoV and unlike MERS-CoV, the spike S protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates the viral attachment and entry into the host cell by binding to its target primary receptor, the ACE2 [6, 7]. To facilitate viral fusion and entry, SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is proteolytically cleaved via cellular proteases into two subunits, S1 responsible for viral binding through its receptor-binding domain and S2 facilitating viral fusion and entry to the cell membrane [6]. Moreover, aside from ACE2, other alternative receptors/co-receptors and cellular proteases were also implicated in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Among these identified receptors are, CD147, known as the basic immunoglobulin or Basigin [8, 9], neuropilin-1 (NRP1) [10], the MERS-CoV receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) [11, 12], angiotensin II receptor type 2 (AGTR2) [13], alanyl aminopeptidase (ANPEP) [14], and glutamyl aminopeptidase (ENPEP) [14]. Furthermore, the classical viral entry through the ACE2 receptor remains the extensively studied model. Consequently, the accumulated acquired knowledge of ACE2 has led to several therapeutic interventions to date such as the introduction of recombinant ACE2 protein as a hypertensive therapeutic target in 2009 [15] and a potent therapeutic target for SARS-related viruses [16,17,18]. However, some discrepancies and unknowns still exist, and further investigations are therefore required. In this context, throughout this review, we will present and discuss what is currently known about ACE2 biogenesis, regulation, and polymorphism with the emphasis on the gaps in our understanding of its intracellular trafficking and the potential of its use as a therapeutic target for COVID-19.

Evolutionary history of ACE2 and its relation to coronaviruses

Controlling and preventing the infectious diseases in humans highly demand understanding and tracking their zoonotic origin. Earlier studies have suggested that coronavirus family, including both SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, are able to infect different species [19]. Coronaviruses were shown to infect humans either directly or indirectly through intermediate species. Phylogenic profiling has shown that bats represent the likely natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV [20, 21]. Of interest, intermediate species like the palm civets and camels were identified to be major transmission sources from animals to humans [22, 23]. Molecular evolution studies and phylogenic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 strongly suggest that SARS-CoV-2 might have crossed the species-specific barrier, with pangolins representing an intermediate species and bat as the main reservoir [24, 25]. ACE2 profiling and pattern conservation analysis have displayed that it is highly conserved within vertebrates, noting that this conservation shows high divergence as the evolutionary distance increases from Homo sapiens [26]. In addition, molecular characterization and sequence alignment analysis of ACE2 show that human and non-human primates display a low evolution rate with high similarity across species except for chicken [27]. Different studies suggested that this observed pattern of human ACE2 utilization might be explained by ancestral recombination events of viruses leading to different strains of the virus and enabling its transmission to humans and across species [28, 29]. Although MERS and SARS coronaviruses infect cells via different receptors, studies display a regulatory and interactive relationship between ACE2 and the MERS-CoV receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) [12, 30]. Similarly, evolutionary studies of DPP-4 show that it has undergone an adaptive evolution that has consequently allowed the transmission of MERS-CoV across species [31]. In addition to its receptor role, DPP-4 represents a T lymphocyte surface marker [32] that is involved in activating the immune response during infections. A combination therapy inhibiting DPP-4 and reducing ACE2 expression was hypothesized to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection via regulating the associated inflammatory reaction [33]. Interestingly, in a single cell RNA-seq analysis of 13 human tissues, DPP-4 has displayed a highly significant co-expression pattern with ACE2 [14]. Additionally, and like ACE2, DPP-4 can either be membrane-bound or shed into a soluble form. Similar to what happens during MERS-CoV infections, soluble circulating level of DPP-4 (sDPP-4) was detected at a reduced level in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 symptoms [30]. It is worth noting that Amati et al. have recently shown that in addition to ACE2, DPP-4 might represent a genomic biomarker that displays an increased expression profile in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs [34]. Altogether, these data provide evidence about the possibility of DPP-4 to act as a co-receptor for SARS-CoV-2; moreover, further understanding of ACE2 characteristics and interactions with the virus and other possibly co-receptors in different species would provide useful insights into the genetic susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and address reasonable tracing of the viral zoonotic origin.

ACE2 structure, tissue distribution, and multiple functions

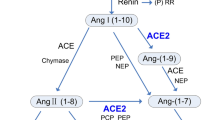

ACE2 gene, mapped to chromosome Xp22 and 40 kb in size, constitutes 22 introns and 18 exons with a remarkable resemblance to ACE’s first 17 exons [4]. ACE2 gene encodes a 120-KDa typical zinc-metalloproteinase type 1 transmembrane protein composed of 805 amino acids. ACE2 protein possesses a unique N-terminal catalytic domain on the extracellular surface and a C-terminal domain serving as a membrane anchor. Despite the considerable similarity between them, ACE and ACE2 do not function similarly and significant differences in their substrate specificities have been observed (Fig. 1). Structural protein studies have shown that both proteins exhibit a highly conserved catalytic domain and share a similar mechanism of action with a different substituted amino acid in the binding pocket [35, 36]. This substitution sterically hinders the access of the substrates to the ACE2 binding site leading to the elimination of ACE-like dipeptidase activity. Like carboxypeptidases, ACE removes C-terminal dipeptide to yield Ang II with injurious effects whereas ACE2 removes only one amino acid residue to produce Ang (1–7) and Ang (1–9) counterbalancing Ang II sequels [5]. Unexpectedly, the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of ACE2 has high homology with the renal protein, collectrin, mapped on chromosome Xp22 as well, which acts as a molecular chaperone that binds to amino acid transporters, like the neutral amino acid transporter B0AT1, and regulates the trafficking of amino acids in the proximal tubules [37,38,39]. ACE2 was later shown to resemble a similar chaperone function. It heterodimerizes with B0AT1 in a tissue-specific manner and regulates membrane trafficking in the intestine where collectrin is absent [40,41,42].

ACE, ACE2 and Collectrin chromosomal location and cellular localizations. The 3 type I transmembrane proteins ACE, ACE2, and collectrin located in the plasma membrane with activity differences. ACE acts as a dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase with 2 catalytic active sites for angiotensin I (Ang I) and angiotensin (1–9) (Ang (1–9)), whereas ACE2 acts as a monocarboxypeptidase possessing one active site that cleaves Ang I and angiotensin II (Ang II). However, collectrin lacks a catalytic activity in its extracellular domain. ACE2 and collectrin gene (CLTRN) are both mapped to chromosome Xp22.2 where ACE is located on chromosome 17q23.3

Moreover, two human ACE2 forms have been reported, the larger form corresponding to the full-length ACE2 with 18 exons and 805 amino acids and the shorter one corresponding to the soluble form of ACE2 (sACE2) which is 555 amino acids in size. sACE2 is obtained by shedding of the protein mainly through a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17) which is demonstrated to maintain its enzymatic activity and play a role in partially attenuating viral entry to the cells [43]. 3D structure analysis of ACE2 reveals a signal peptide sequence composed of 18 amino acids, an extracellular sequence (18-740) which contains the active carboxypeptidase domain, a transmembrane domain (741–761) and a cytoplasmic domain (762–805) which together the latter two form the collectrin homology domain (Fig. 2).

ACE2 3D-structure and isoforms. a 3D structure of ACE2 adopted from Towler et al. [36] and drawn in iCn3D using PBD ID: 1R4L. The structure was modified based on the newly identified N-glycosylation sites labeled in black. b ACE2 exists in 4 different isoforms along with a soluble form cleaved at residues 716–741 and constitutes 555 amino acids lacking the transmembrane collectrin homology domain. ACE2 isoform 2 shows a truncation of the full-length ACE2 with 100% homology in the 786 residues. ACE2 isoform 3 displays deletions in the transmembrane and collectrin homology domains leading to 95% similarity with ACE2 represented by gradient color in the corresponding domains. The fourth isoform with shorter N-terminus, lacking the carboxypeptidase activity and inability to bind to SARS-CoV-2. SP signal peptide

In addition, to date, 6 different transcript variants of human ACE2 are available in the GeneBank (transcript variant 1: NM_001371415.1, transcript variant 2: NM_021804.3, transcript variant 3: NM_001386259.1, transcript variant 4: NM_00138260.1, transcript variant 5: NM_001388425.1, and transcript variant 6: NM_001389402.1) corresponding to four ACE2 isoforms, other than sACE2, illustrated in Fig. 2b. Aside from the full-length isoform (805 amino acids) that is coded by transcript variants 1 and 2, three others have been reported. Transcript variant 3 encodes ACE2 isoform 2 that is a 786 amino acid protein. Based on blast sequence alignment, it is 100% identical with the full-length ACE2, where it is truncated at the cytoplasmic domain and lacks a collectrin homology domain, whereas the third ACE2 isoform (isoform 3) is generated by transcript variants 4 and 6 and is composed of 694 amino acids with 95% similarity with the full-length ACE2, where these transcripts lack some exons in the 3′UTR region and some deletions occur in the collectrin homology domain. It is worth noting that the role of these two isoforms in the SARS viral infections remains unidentified yet. However, a fourth isoform, known as dACE2 or MIRb-ACE2 has been identified, it lacks the carboxypeptidase activity and cannot bind to SARS-CoV-2. MIRb-ACE2 is a tissue-specific isoform and unstable truncated product. It has a shorter N-terminus with different 5′UTR and 5′ coding region compared to full-length ACE2 [44, 45].

ACE2 belongs to a family of transmembrane proteins that has wide tissue distribution. The observed difference in the cytoplasmic C-terminal sequence between ACE and ACE2 could explain the preferential localization of ACE2 on the apical membrane of polarized cells whilst ACE being localized on both the apical and basolateral membrane of epithelial cells [46]. Initial analysis has indicated that ACE2 expression is mainly in the rodent’s heart [3] and more precisely in cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts [47, 48]. However, in 2002, a detailed transcriptional profiling of ACE2 using real-time PCR has shown that transcribed ACE2 is expressed in 72 human tissues with higher expression in cardiovascular and renal systems [49]. Recently, bioinformatic analysis of publicly available data from human samples has generated extensive information about ACE2 distribution in tissues and cell types. Hikmet et al. have reported the expression pattern of ACE2 in more than 150 cell types, where the highest expression was observed mainly in the enterocytes, cardiomyocytes, and renal tubules and expression in the lungs was only limited to few subsets of cells [50]. Analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data has shown that ACE2 mRNA transcript is mostly detected in the alveolar type 2 cells of the lungs [51, 52]. The ACE2 expression profile was rarely investigated in COVID-19 patients, except for a study that displays an increased expression of mRNA in the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, with no data about its protein expression [34]. Furthermore, protein expression of ACE2 was initially identified in the heart, kidney, and testis [3,4,5], where immunolocalization studies have later demonstrated that it also exists on the surface of cells that are in contact with the cellular environment like the lung’s alveolar epithelial cells and the small intestine’s enterocytes [53]. ACE2 expression profiles were also affected in response to diseases. ACE2 protein expression analyzed by immunohistochemistry in bronchial and alveolar samples displayed a significant increase in type 2 diabetic subjects compared to controls, unlike its mRNA expression that was detected indifferent analyzed by RT-PCR [54]. In addition, ACE2 was also localized in the brain [55], islets of Langerhans of the pancreatic tissue [56] and bone [57] with no significant expression in the lymphatic system and lymphoid organs [53, 58].

ACE2 polymorphic footprint in health and disease

In order to find an association with diseases, genetic variable signature has been extensively studied in different populations through single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). There are different factors, like age and ethnicity that affect the occurrence of SNPs and might consequently contribute to significant phenotypic changes and diseases’ outcomes. In this setting, ACE2 polymorphism and its association with hypertension were reported in different populations including the Chinese population with three major ACE2 variants (rs4830542, rs4240157, and rs4646155) [59], the Canadian population with another three different variants (rs233575, rs2074192, and rs2158083) [60], the Brazilian population with ACE2 G8790A mutation in combination with ACE I/D [61], and the Indian population with the ACE2 rs2106809 mutant [62]. It is not fully elucidated to date whether all these hypertension-related mutations affect the susceptibility/severity during SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, ACE2 rs2285666 was significantly correlated to lower infection rate in the Indian population [63] and ACE2 rs2074192 was significantly associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes in obese male smokers of age greater than 50 [64].

In an attempt to discover the association between COVID-19 and ACE2 polymorphic variations, being its major host cellular receptor, Cao and colleagues have investigated 1700 ACE2 coding variants collected from the China Metabolic Analytics Project and 1000 Genome Project databases. Their results demonstrated that no natural resistance mutations for SARS-CoV-2 S binding protein were detected in the studied populations. In addition, 32 variants were identified to potentially affect the amino acid sequence of ACE2 with 7 major variations unevenly distributed in different populations (Lys26Arg, Ile468Val, Ala627Val, Asn638Ser, Ser692Pro, Asn720Asp, and Leu731Ile/Leu731Phe) [65]. Notably, in another large population study, authors have identified natural ACE2 variants that might affect host susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, they have also demonstrated that some variants potentially enhance susceptibility while others showed reduced binding to SARS-CoV-2 [66]. Among the ones that enhanced ACE2 affinity for the S protein is the Lys26Arg missense mutation. Lys26Arg along with another mutation, the Asn720Asp, were characterized by Al-Mulla and colleagues, in a preprint, as the most frequent missense variants of ACE2 in different global datasets [67]. Conversely, these results do not apply to an Italian COVID-19-positive population, where Novelli and colleagues have shown that no significant association is present between ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 severity, speculating that susceptibility-related variants might be located in the non-coding region and contributing to the regulation of ACE2 activity [68]. Major ACE2 missense mutants involved in hypertension and COVID-19 are listed in Table 1. Of interest, none of these mutations has been clinically validated, where Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD Professional 2020.3) displays only two reported ACE2 missense/nonsense mutations that are phenotypically related to autism spectrum disorder [69] and west syndrome [70].

Epigenetic variation of ACE2

The localization of the ACE2 gene on the X chromosome raises the question of balance in the expression profiles between genders. Various studies have shown significant differences between males and females in ACE2 expression [81,82,83,84]. These findings were explained by identifying ACE2 as an escapee gene that undergoes incomplete X inactivation and shows a heterogenous sex-bias profile that is often shared across tissues [85]. X chromosome inactivation was shown to be greatly affected by epigenetic variations like the DNA-methylation that also affects the ACE2 expression profile [86].

Modifications in the DNA and chromatin structures are marked as epigenetic variations that were shown to play an important role in several human diseases like cardiovascular ones [87, 88]. Interestingly, recent studies have suggested that ACE2 production rate is controlled by its epigenetic modifications, where methylation of ACE2 gene near the transcription start site is found to be associated with the age- and gender-dependent variations of ACE2 with the lowest rate of methylation in the lungs and the highest in neurons where ACE2 protein is not detected [89]. Along these findings, ACE2 profiles were also shown to display a significant correlation with histone modification-related genes in the human lungs [90]. Additionally, the results of another study have previously demonstrated that ACE2 promoter was hypermethylated in hypertensive patients with a significant difference between males and females [91], where COVID-19 patients as well have displayed differential methylation pattern in ACE2 of blood samples [92] which further requires testing in the respiratory samples.

Aside from the pre-transcriptional regulation, the ACE2 mRNA level displays an epigenetic signature through the putative short non-coding micro-RNA regulation network. Several studies have reported new miRNAs that are involved with ACE2 expression either via hampering its translation or through degrading its corresponding protein. A recent bioinformatic study has identified 1954 miRNAs involved in the ACE2 regulating network [93]. miRNAs were either directly regulating ACE2 like miR-421, miR-125b, and miR-483-3p via having a putative site in its 3′UTR region [88, 94,95,96] or indirectly affecting ACE2 expressions like miR-181a and miR-4262 through affecting RAS components and target proteins (apoptotic Bcl2), respectively [97, 98]. A list of the microRNAs that target ACE2 is displayed in Table 2.

In addition, other factors like smoking and sex hormone can also induce epigenetic modifications in the genome. Several studies conducted on the sex hormone have shown a correlation with ACE2 expression level which could also contribute to the sex-biased susceptibility of COVID-19. The female sex steroid 17β-estradiol (E2) was shown to regulate ACE2 expression, where it induces downregulation in the kidney and the differentiated airway epithelial cells [83, 106]. Conversely, in the atrial heart tissue, ACE2 expression was upregulated through the E2-estrogen receptor alpha-activated pathway [107]. In addition, another study on the male hormone, testosterone, was reported to upregulate ACE2 expression [108]. Furthermore, cigarette smoking was demonstrated to enhance ACE2 expression which also presented a risk factor for the progression of COVID-19 with more severe complications [109, 110].

Subcellular localization and intracellular trafficking of ACE2

Among the 10% proteins that are destined to the plasma membrane [111], nascently biosynthesized ACE2 traffics to its intended location in the cell via a highly regulated machinery that includes different subcellular compartments. Translated proteins are inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) via their signal peptides, where they undergo folding into their correct conformations. Post-translational modifications of the proteins, such as attaching carbohydrate moieties, a process named glycosylation which is a common modification of secretory pathway targeted proteins, is initiated in the ER. In order to exit the ER, proteins need to be fully folded and assembled (in case of multi-subunit complexes) before they are allowed to exit the ER. Misfolded proteins and orphaned subunits of protein complexes are retained in the ER and transported to the cytosol where they are degraded by the proteasome through ERAD (endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation) degradation process [112, 113]. At the ER exist sites, folded proteins are transported from the ER by transport vesicles into the Golgi apparatus through the cis Golgi network. Proteins are further processed in the Golgi including carbohydrate remodeling, sulfation, proteolysis, and phosphorylation. Processed proteins are then sorted and exit the Golgi through the trans-Golgi network via the secretory pathway in which they are secreted or targeted to subcellular compartments such as the plasma membrane [114].

Generally, proteins composed of more than 100 amino acids, including ACE2, undergo co-translational translocation into the ER while being translated. Unlike the small proteins that cross the ER membrane, newly synthesized ACE2 is targeted to the translocon (ER membrane channel) via its 17 amino acid N-terminal signal sequence. As translation proceeds, ACE2 binds to the channel and passes to the ER membrane where the ribosome is dissociated [115]. Once ACE2 is well folded and N-glycosylated in the ER, it exits through transport vesicles and enters the Golgi apparatus through its cis face. In the Golgi, ACE2 undergoes further modifications and packaging and is then transported to the plasma membrane by vesicular transport (Fig. 3a) [116]. As mentioned previously, the intracellular localization of a protein to the plasma membrane is a highly regulated machinery that requires interaction with accessory proteins. Unfortunately, ACE2 accessory proteins are not yet investigated, except for the actin-bundling protein fascin-1 that has displayed differential interaction with ACE2 in the HEK293T cell model in an Ang II-dependent manner [117]. Characterizing these interactors and deciphering their role during intracellular trafficking might represent a promising therapeutic tool to decrease ACE2 availability at the cellular membrane.

ACE2 synthesis, trafficking, proteolysis, and internalization. a Synthesis of ACE2 protein and its translocation to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through Golgi apparatus towards the plasma membrane via transport vesicles. Red stars correspond to post-translational modifications. b Truncation of ACE2 by ADAM17 and the release of soluble ACE2 (sACE2) into the extracellular environment. c Internalization of ACE2 in response to increased angiotensin II (Ang II) via ubiquitylation of ACE2 and interaction with angiotensin type I receptor (AT1R). The latter complex is endocytosed where ACE2 is degraded by the lysosome and AT1R is recycled and transported back to the membrane. d ACE2 internalization in response to SARS-CoV-2 binding via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. ACE2 is recycled and transported to the membrane and SARS-CoV-2 is replicated inside the host cell

To date, several glycosylation sites have been identified on ACE2. In fact, seven asparagine residues were detected to undergo N-glycosylation in human ACE2 (N53, N90, N103, N322, N432, N546, and N690) (Fig. 2a) [118]. The same study has suggested that glycosylation of ACE2 had no effect on its binding affinity with the S protein of SARS-CoV-2. However, these data contradict other studies that have reported N90 and N322 glycosylation to be interfering with the binding and contributing significantly to the infectivity of the virus [119, 120]. Proper N-glycosylation is expected to be important for the efficient trafficking of the receptor to the plasma membrane. However, a study by Zhao and colleagues showed that inhibiting ER-resident glucosidases, responsible for trimming sugars prior to protein folding, altered the glycan structure of ACE2. This alteration did not affect neither ACE2 cellular expression nor its binding to SARS-CoV, but it showed impaired ability in the viral-induced membrane fusion [121]. Similarly, in the context of glycosylation, a study by Vincent and colleagues have demonstrated that effective doses’ treatments of chloroquine and NH4CL, not only affected the viral proteins, but also induced impaired terminal glycosylation of ACE2 and increased intracellular mobility in the ER and the Golgi. However, these modifications displayed no effect on ACE2 localization to the cellular surface [122]. Moreover, modifications other than glycosylation like methylation have also been identified on human ACE2 at different sites, unlike phosphorylation and acetylation post translational modifications that were not detected [118].

Type I transmembrane proteins are subjected to shedding, also known as proteolytic cleavage, where the protein’s ectodomain is cleaved by a protease and is released extracellularly in order to control the protein’s expression and function [123]. ACE2 is catalytically cleaved by ADAM17, a metalloprotease family member, near the transmembrane domain, between the residues 716 and 741, leading to an enzymatically active soluble ACE2 (Fig. 3b) [43, 124]. Interestingly, a mutation at the 584 residues has inhibited the shedding activity but did not affect the trafficking of the mutant ACE2 to the cell surface, noting that several mutations at different residues have displayed no effect (580, 581, 582, 583, and 604) neither on ACE2 shedding nor surface targeting [43]. The shedding event of ACE2 is regulated by different stimuli. Increased soluble ACE2 levels have been reported in cardiovascular diseases contributing to higher blood pressure [125]. In addition, spike protein binding to the ACE2 receptor induces its cleavage; however, it does not augment the viral infectivity [126]. TMPRSS2, type II transmembrane serine protease, was demonstrated to have a competitive cleavage activity that removes a C-terminal fragment of ACE2 and contributes to further virulence during SARS-CoV infections [126,127,128].

Furthermore, ACE2 was shown to display an internalization pattern under different stimulations. During hypertension, decreased ACE2 protein expression level contributed to an internalization compensatory mechanism in response to increased Ang II, mediated through the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1R) [129]. ACE2 displayed enhanced ubiquitination and interacted with AT1R, where the latter is recycled and transported back to the membrane via endosomes, whereas ACE2 was degraded in the lysosome (Fig. 3c). In addition, ACE2 was also internalized during SAR-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 infections via a clathrin-mediated endocytosis [130, 131] in which it was suggested that ACE2 is recycled back to the cell surface and the virus is further replicated in the cell (Fig. 3d) [130].

ACE2 as a therapeutic target

Given the protective effect that it displays, ACE2 represents a potent therapeutic target to prevent and treat several cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension. Strategies that aim to enhance the protective role of ACE2 like ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB) have shown effectiveness in treating high blood pressure and some other cardiovascular issues. In this context, treatments were based on activating ACE2. However, researchers have developed a new strategy based on exogenous administration of ACE2 in which recombinant human ACE2 (rhACE2) was used and demonstrated encouraging cardioprotective, anti-fibrotic effects, and protection against lung injury [15, 132, 133].

Paradoxically, ACE2 acts as a double-edged sword where this protective effect is abolished in the presence of SARS viral infections. Conversely, therapeutic strategies could aim to decrease ACE2 expression or alter its binding affinity to SARS S protein and consequently reduce the viral entry to host cells. Pharmacologic RAS inhibition through ACE inhibitors or ARBs was hypothesized to upregulate ACE2 in diabetic and hypertensive patients which will subsequently amplify the viral infection [134]. However, the concerns regarding the potential harmful effect of ACE inhibitors and ARBs were not confirmed to be true. A study by Peng and colleagues has shown that the use of ACEI/ARBs does not affect the mortality rate in cardiovascular patients infected with COVID-19 [135]. Furthermore, another study has demonstrated that RAS inhibition significantly contributes to lower virulence [136]. Interestingly, the administration of rhACE2 to SARS-CoV-2 patients could display a positive approach due to its hypothetical dual function. Increasing ACE2 availability could contribute to slowing down viral entry through its competitive binding to the viral S protein and could protect the lung against the subsequent injury through its classical protective role [137]. Monteil and colleagues have previously demonstrated that soluble rhACE2 was able to alter the early infection stages of SARS-CoV-2 in engineered human kidney organoids [138]. Noting that it was not tested in any animal model [139], the use of recombinant human ACE2 was remarkably tolerated at different doses in healthy human subjects and patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome [16, 17]. To date, rhACE2 (APN01) is being assessed as a treatment for patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Currently, the pilot clinical study has 200 participants and is in phase 2 clinical trial [18]. In this context, genetically modified mouse models have been proposed to enhance preclinical studies in COVID-19 research [140].

Additionally, in a new nanotechnology approach, it was suggested that ACE2 nanoparticles applied to the protective personal equipment (masks, gloves, and clothes) could present an effective strategy in tackling the virus and preventing its entry to the host cells [141]. Moreover, none of these strategies has been approved yet and further studies are still required.

Discussion

Given the multifunction, complexity, and dynamic nature of ACE2, the present understanding of its structure and function represents the beginning of guidance into therapeutic solutions. The presence of conflicting data highlights the importance of systems biology studies of the viral infections that include different variables to provide a holistic perspective of how our system interacts and responds to SARS-CoV-2 infection, noting its wide distribution in human tissues [49, 50]. Reductionist studies of ACE2 have led to a massive accumulation of data; however, unfortunately, no effective medication for COVID-19 is available to date. After its synthesis, ACE2 is subjected to different interactions and regulations that might be occurring simultaneously and not separately, affecting its cellular trafficking, localization, and expression. These interactions might differ between individuals based on their genetic signature and consequently may lead to variable virulence and infectivity.

The presence of genetic variations in the host cellular receptor could greatly contribute to the observed variable susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Their occurrence in the promoter region of the ACE2 gene could consequently lead to decreasing its cellular expression. Moreover, the presence of these variants in the coding region would probably lead to altering its amino acid sequence that might modify its structure and alter its plasma membrane targeting and as a result reduce the interaction with SARS-CoV-2 S protein. The latter has been also shown in a study by Guo et al. where different missense mutations were shown to affect ACE2 secondary structure and weaken its activity [79]. A recently published study that investigates the impact of ACE2 mutants on COVID-19 susceptibility shows that ACE2 SNPs could greatly influence its folding, its expression, and its interacting miRNA and consequently affecting the viral susceptibility [80]. Compared to ACE2, a point mutation on the 1069 residue of ACE, located in the C-terminal domain, is reported to be responsible for autosomal renal tubular dysgenesis (RTD) disease. This mutation has led to retaining ACE in the ER and increased its degradation leading consequently to its decreased cell surface localization [142]. Besides, ACE was reported to interact with immunoglobulin-binding protein (BiP) chaperone that resides in the ER, its overexpression leads to the retention of ACE in the ER and decreases its cell surface expression which suggests transient interaction with BiP for optimal transport. This study has demonstrated that BiP affects exclusively the transport of ACE rather than its synthesis [143]. Moreover, the use of pharmacological chaperones and proteasome inhibitors prevented intracellular degradation and rescued mutant ACE to the plasma membrane [144]. Additionally, in the context of RTD, several mutations at different residues were evaluated. Missense (at 594 and 828 residues) and truncated mutants (at 1136 and 1145 residues) were also retained in ER and displayed no plasma membrane expression, where another mutant at 1180 has displayed partial ER retention and delayed cell surface expression compared to wild type-ACE [145]. Whether the different identified mutations and isoforms of ACE2 could modify its trafficking and lead to cellular retention is not tested yet. Recently, Gurumurthy et al. have proposed different genetically engineered mouse models that can be used to engineer the different ACE2 identified mutations in vivo and assess their effects [140]. In addition, a combination of these mutants could also occur together leading to a further decreased ACE2 membrane expression. In a deep mutagenesis study involving the soluble ACE2, combining different engineered single mutations together showed higher binding to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [146]. Understanding the trafficking and secretory pathways of classical and mutated ACE2 shall provide potential trafficking modulators that can be targeted to improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, “in every angel a demon hides and in every demon an angel strides.” The angelic protective role of ACE2 is interchanged with the emergence of SARS viral infections and the evil ACE2 as a host cellular receptor can potently be reciprocated and act as a therapeutic target to treat COVID-19 patients. Through this review, we highlight the importance of further mutational screening, trafficking assessment, and systems biology studies of ACE2 and their role in the generation of a unique individual fingerprint that might explain why some people are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 and others are not. Consequently, this could help us understand the downstream mechanism of ACE2-mediated infection and possibly characterize novel therapeutic strategies for tackling COVID-19.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme Inhibitor

- ADAM17:

-

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17

- Ang II:

-

Angiotensin II

- Ang(1–7):

-

Angiotensin (1–7)

- Ang(1–9):

-

Angiotensin (1–9)

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- AT1R:

-

Angiotensin II type I receptor

- B0AT1:

-

Neutral amino acid transporter

- BiP:

-

Binding immunoglobulin protein

- CLTRN:

-

Collectrin

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-2019

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- I/D:

-

Insertion/deletion

- RAS:

-

Renin-angiotensin system

- rhACE2:

-

Recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- RTD:

-

Renal tubular dysgenesis

- sACE2:

-

Soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome - coronavirus 2

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SP:

-

Signal peptide

- TMPRSS2:

-

Type II transmembrane serine protease

References

Tigerstedt R, Bergman PQ. Niere und Kreislauf1. Skand Arch Für Physiol. 1898;8:223–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1898.tb00272.x.

Skeggs LT, Kahn JR, Shumway NP. The preparation and function of the hypertensin-converting enzyme. J Exp Med. 1956;103:295–9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2136590/. Accessed 24 Oct 2020.

Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. 2000;87:E1–9.

Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33238–43.

Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00786.

Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:562–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y.

Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7.

Wang K, Chen W, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Lian J-Q, Du P, et al. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x.

Ulrich H, Pillat MM. CD147 as a target for COVID-19 treatment: suggested effects of azithromycin and stem cell engagement. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16:434–40.

Daly JL, Simonetti B, Klein K, Chen K-E, Williamson MK, Antón-Plágaro C, et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science. 2020;370:861–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3072.

Li Y, Zhang Z, Yang L, Lian X, Xie Y, Li S, et al. The MERS-CoV receptor DPP4 as a candidate binding target of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. iScience. 2020;23:101160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101160.

Vankadari N, Wilce JA. Emerging COVID-19 coronavirus: glycan shield and structure prediction of spike glycoprotein and its interaction with human CD26. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:601–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1739565.

Cui C, Huang C, Zhou W, Ji X, Zhang F, Wang L, Zhou Y, Cui Q. AGTR2, one possible novel key gene for the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into human cells. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2020.3009099.

Qi F, Qian S, Zhang S, Zhang Z. Single cell RNA sequencing of 13 human tissues identify cell types and receptors of human coronaviruses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;526:135–40.

Wysocki J, Ye M, Rodriguez E, González-Pacheco FR, Barrios C, Evora K, et al. Targeting the degradation of angiotensin II with recombinant ACE2: prevention of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:90–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138420.

Haschke M, Schuster M, Poglitsch M, Loibner H, Salzberg M, Bruggisser M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in healthy human subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52:783–92.

Khan A, Benthin C, Zeno B, Albertson TE, Boyd J, Christie JD, et al. A pilot clinical trial of recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2017;21:234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1823-x.

LI Y. A Randomized, Open Label, Controlled clinical study to evaluate the recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (rhACE2) in adult patients with COVID-19. Clinical trial registration.clinicaltrials.gov; 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04287686. Accessed 6 Dec 2020.

Masters PS. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. In: Advances in Virus Research: Academic Press; 2006. p. 193–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3.

Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–9.

Ithete NL, Stoffberg S, Corman VM, Cottontail VM, Richards LR, Schoeman MC, et al. Close relative of human middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat. South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1697–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1910.130946.

Wang M, Yan M, Xu H, Liang W, Kan B, Zheng B, et al. SARS-CoV infection in a restaurant from palm civet. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1860–5. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1112.041293.

Hemida MG, Chu DKW, Poon LLM, Perera RAPM, Alhammadi MA, Ng H-Y, et al. MERS coronavirus in dromedary camel herd. Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1231–4.

Lopes LR, de Mattos CG, Paiva PB. Molecular evolution and phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and hosts ACE2 protein suggest Malayan pangolin as intermediary host. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:1593–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-020-00321-1.

Wong G, Bi Y-H, Wang Q-H, Chen X-W, Zhang Z-G, Yao Y-G. Zoonotic origins of human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19/SARS-CoV-2): why is this work important? Zool Res. 2020;41:213–9. https://doi.org/10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.031.

Braun M, Sharon E, Unterman I, Miller M, Shtern AM, Benenson S, et al. ACE2 co-evolutionary pattern suggests targets for pharmaceutical intervention in the COVID-19 pandemic. iScience. 2020;23:101384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101384.

Li R, Qiao S, Zhang G. Analysis of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) from different species sheds some light on cross-species receptor usage of a novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV. J Infect. 2020;80:469–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.013.

Wells HL, Letko M, Lasso G, Ssebide B, Nziza J, Byarugaba DK, et al. The evolutionary history of ACE2 usage within the coronavirus subgenus Sarbecovirus. bioRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.07.190546.

Li X, Giorgi EE, Marichannegowda MH, Foley B, Xiao C, Kong X-P, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabb9153. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb9153.

Schlicht K, Rohmann N, Geisler C, Hollstein T, Knappe C, Hartmann K, et al. Circulating levels of soluble dipeptidylpeptidase-4 are reduced in human subjects hospitalized for severe COVID-19 infections. Int J Obes. 2020;44:2335–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00689-y.

Cui J, Eden J-S, Holmes EC, Wang L-F. Adaptive evolution of bat dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (dpp4): implications for the origin and emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Virol J. 2013;10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-10-304.

Schön E, Demuth HU, Barth A, Ansorge S. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV of human lymphocytes. Evidence for specific hydrolysis of glycylproline p-nitroanilide in T-lymphocytes. Biochem J. 1984;223:255–8. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2230255.

Phyu Khin P, Cha S-H, Jun H-S, Lee JH. A potential therapeutic combination for treatment of COVID-19: synergistic effect of DPP4 and RAAS suppression. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110186.

Amati F, Vancheri C, Latini A, Colona VL, Grelli S, D’Apice MR, et al. Expression profiles of the SARS-CoV-2 host invasion genes in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05143.

Guy JL, Jackson RM, Acharya KR, Sturrock ED, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2): comparative modeling of the active site, specificity requirements, and chloride dependence. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13185–92.

Towler P, Staker B, Prasad SG, Menon S, Tang J, Parsons T, et al. ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17996–8007.

Zhang H, Wada J, Hida K, Tsuchiyama Y, Hiragushi K, Shikata K, et al. Collectrin, a collecting duct-specific transmembrane glycoprotein, is a novel homolog of ACE2 and is developmentally regulated in embryonic kidneys. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17132–9. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M006723200.

Danilczyk U, Sarao R, Remy C, Benabbas C, Stange G, Richter A, et al. Essential role for collectrin in renal amino acid transport. Nature. 2006;444:1088–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05475.

Malakauskas SM, Quan H, Fields TA, McCall SJ, Yu M-J, Kourany WM, et al. Aminoaciduria and altered renal expression of luminal amino acid transporters in mice lacking novel gene collectrin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F533–44.

Kowalczuk S, Bröer A, Tietze N, Vanslambrouck JM, Rasko JEJ, Bröer S. A protein complex in the brush-border membrane explains a Hartnup disorder allele. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2008;22:2880–7.

Camargo SMR, Singer D, Makrides V, Huggel K, Pos KM, Wagner CA, et al. Tissue-specific amino acid transporter partners ACE2 and collectrin differentially interact with hartnup mutations. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:872–82.

Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb2762.

Jia HP, Look DC, Tan P, Shi L, Hickey M, Gakhar L, et al. Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L84–96.

Onabajo OO, Banday AR, Stanifer ML, Yan W, Obajemu A, Santer DM, et al. Interferons and viruses induce a novel truncated ACE2 isoform and not the full-length SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1283–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00731-9.

Ng KW, Attig J, Bolland W, Young GR, Major J, Wrobel AG, et al. Tissue-specific and interferon-inducible expression of nonfunctional ACE2 through endogenous retroelement co-option. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1294–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00732-8.

Warner FJ, Lew RA, Smith AI, Lambert DW, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), but not ACE, is preferentially localized to the apical surface of polarized kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39353–62. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M508914200.

Burrell LM, Risvanis J, Kubota E, Dean RG, MacDonald PS, Lu S, et al. Myocardial infarction increases ACE2 expression in rat and humans. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:369–75 discussion 322-324.

Guy JL, Lambert DW, Turner AJ, Porter KE. Functional angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is expressed in human cardiac myofibroblasts. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:579–88. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040139.

Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, Clark KL. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:107–10.

Hikmet F, Méar L, Edvinsson Å, Micke P, Uhlén M, Lindskog C. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:e9610. https://doi.org/10.15252/msb.20209610.

Ortiz ME, Thurman A, Pezzulo AA, Leidinger MR, Klesney-Tait JA, Karp PH, et al. Heterogeneous expression of the SARS-Coronavirus-2 receptor ACE2 in the human respiratory tract. EBioMedicine. 2020;60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102976.

Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Ma Y, Zuo W. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:756–9. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE.

Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis M, Lely A, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1570.

Wijnant SRA, Jacobs M, Eeckhoutte HPV, Lapauw B, Joos GF, Bracke KR, et al. Expression of ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, in lung tissue of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2020;69:2691–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/db20-0669.

Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R373–81.

Niu M-J, Yang J-K, Lin S-S, Ji X-J, Guo L-M. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 leads to impaired glucose homeostasis in mice. Endocrine. 2008;34:56–61.

Queiroz-Junior CM, Santos ACPM, Galvão I, Souto GR, Mesquita RA, Sá MA, et al. The angiotensin converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas receptor axis as a key player in alveolar bone remodeling. Bone. 2019;128:115041.

Li J, Gao J, Xu Y, Zhou T, Jin Y, Lou J. Expression of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptors, ACE2 and CD209L in different organ derived microvascular endothelial cells. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:833–7.

Luo Y, Liu C, Guan T, Li Y, Lai Y, Li F, et al. Association of ACE2 genetic polymorphisms with hypertension-related target organ damages in south Xinjiang. Hypertens Res Off J Jpn Soc Hypertens. 2019;42:681–9.

Malard L, Kakinami L, O’Loughlin J, Roy-Gagnon M-H, Labbe A, Pilote L, et al. The association between the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 gene and blood pressure in a cohort study of adolescents. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-14-117.

Pinheiro DS, Santos RS, Jardim PCBV, Silva EG, Reis AAS, Pedrino GR, et al. The combination of ACE I/D and ACE2 G8790A polymorphisms revels susceptibility to hypertension: a genetic association study in Brazilian patients. PloS One. 2019;14:e0221248.

Patnaik M, Pati P, Swain SN, Mohapatra MK, Dwibedi B, Kar SK, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 gene polymorphisms with essential hypertension in the population of Odisha. India. Ann Hum Biol. 2014;41:145–52.

Srivastava A, Bandopadhyay A, Das D, Pandey RK, Singh V, Khanam N, et al. Genetic association of ACE2 rs2285666 polymorphism with COVID-19 spatial distribution in India. Front Genet. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.564741.

Hamet P, Pausova Z, Attaoua R, Hishmih C, Haloui M, Shin J, Paus T, Abrhamowicz M, Gaudet D, Santucci L, Kotchen TA, Cowley AW, Hussin J, Tremblay J. SARS-COV-2 RECEPTOR ACE2 GENE is associated with hypertension and SEVERity of COVID 19: interaction with sex, obesity and SMOKING. Am J Hypertens. 2021;hpaa223. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa223.

Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, Huang P, Sun X, et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell Discov. 2020;6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0147-1.

Stawiski EW, Diwanji D, Suryamohan K, Gupta R, Fellouse FA, Sathirapongsasuti JF, et al. Human ACE2 receptor polymorphisms predict SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. bioRxiv. 2020;:2020.04.07.024752. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.07.024752.

Al-Mulla F, Mohammad A, Madhoun AA, Haddad D, Ali H, Eaaswarkhanth M, et al. A comprehensive germline variant and expression analyses of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and SARS-CoV-2 activator FURIN genes from the Middle East: combating SARS-CoV-2 with precision medicine. bioRxiv. 2020:2020.05.16.099176. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.16.099176.

Novelli A, Biancolella M, Borgiani P, Cocciadiferro D, Colona VL, D’Apice MR, et al. Analysis of ACE2 genetic variants in 131 Italian SARS-CoV-2-positive patients. Hum Genomics. 2020;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-020-00279-z.

Al-Mubarak B, Abouelhoda M, Omar A, AlDhalaan H, Aldosari M, Nester M, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals inherited and de novo variants in autism spectrum disorder: a trio study from Saudi families. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5679. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06033-1.

Peng J, Wang Y, He F, Chen C, Wu L, Yang L, et al. Novel West syndrome candidate genes in a Chinese cohort. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:1196–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12860.

Fan Z, Wu G, Yue M, Ye J, Chen Y, Xu B, et al. Hypertension and hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy are associated with ACE2 genetic polymorphism. Life Sci. 2019;225:39–45.

Yang J-K, Zhou J-B, Xin Z, Zhao L, Yu M, Feng J-P, et al. Interactions among related genes of renin-angiotensin system associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2271–3.

Zhang Q, Cong M, Wang N, Li X, Zhang H, Zhang K, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene polymorphism and enzymatic activity with essential hypertension in different gender: a case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12917.

Pan Y, Wang T, Li Y, Guan T, Lai Y, Shen Y, et al. Association of ACE2 polymorphisms with susceptibility to essential hypertension and dyslipidemia in Xinjiang, China. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17:241.

Liu C, Li Y, Guan T, Lai Y, Shen Y, Zeyaweiding A, et al. ACE2 polymorphisms associated with cardiovascular risk in Uygurs with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:127.

He J, Lu Y-P, Li J, Li T-Y, Chen X, Liang X-J, et al. Fetal but not maternal angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)-2 gene Rs2074192 polymorphism is associated with increased risk of being a small for gestational age (SGA) newborn. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:1596–606.

Wu X, Zhu B, Zou S, Shi J. The association between ACE2 gene polymorphism and the stroke recurrence in Chinese population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc. 2018;27:2770–80.

Kumar A, Rani B, Sharma R, Kaur G, Prasad R, Bahl A, et al. ACE2, CALM3 and TNNI3K polymorphisms as potential disease modifiers in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018;438:167–74.

Guo X, Chen Z, Xia Y, Lin W, Li H. Investigation of the genetic variation in ACE2 on the structural recognition by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). J Transl Med. 2020;18:321. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02486-7.

Paniri A, Hosseini MM, Moballegh-Eslam M, Akhavan-Niaki H. Comprehensive in silico identification of impacts of ACE2 SNPs on COVID-19 susceptibility in different populations. Gene Rep. 2021;22:100979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100979.

Xudong X, Junzhu C, Xingxiang W, Furong Z, Yanrong L. Age- and gender-related difference of ACE2 expression in rat lung. Life Sci. 2006;78:2166–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.038.

Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Westwood BM, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC. Sex differences in circulating and renal angiotensins of hypertensive mRen(). Lewis but not normotensive Lewis rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H10–20. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01277.2007.

Liu J, Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, Zhu JJ, Arnold AP, et al. Sex differences in renal angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) activity are 17β-oestradiol-dependent and sex chromosome-independent. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2042-6410-1-6.

Chen J, Jiang Q, Xia X, Liu K, Yu Z, Tao W, et al. Individual variation of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 gene expression and regulation. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13168. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13168.

Tukiainen T, Villani A-C, Yen A, Rivas MA, Marshall JL, Satija R, et al. Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:244–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24265.

Sawalha AH, Zhao M, Coit P, Lu Q. Epigenetic dysregulation of ACE2 and interferon-regulated genes might suggest increased COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in lupus patients. Clin Immunol Orlando Fla. 2020;215:108410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108410.

Yamada Y, Nishida T, Horibe H, Oguri M, Kato K, Sawabe M. Identification of hypo- and hypermethylated genes related to atherosclerosis by a genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:1355–40. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2014.1692.

Xue S, Liu D, Zhu W, Su Z, Zhang L, Zhou C, et al. Circulating MiR-17-5p, MiR-126-5p and MiR-145-3p are novel biomarkers for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Front Physiol. 2019;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00123.

Corley MJ, Ndhlovu LC. DNA methylation analysis of the COVID-19 host cell receptor, angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 gene (ACE2) in the respiratory system reveal age and gender differences; 2020. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202003.0295.v1.

Pinto BGG, Oliveira AER, Singh Y, Jimenez L, Gonçalves ANA, Ogava RLT, et al. ACE2 expression is increased in the lungs of patients with comorbidities associated with severe COVID-19. J Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa332.

Fan R, Mao S-Q, Gu T-L, Zhong F-D, Gong M-L, Hao L-M, et al. Preliminary analysis of the association between methylation of the ACE2 promoter and essential hypertension. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:3905–11. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2017.6460.

Steyaert S, Trooskens G, Delanghe JR, Criekinge WV. Differential methylation as a mediator of COVID-19 susceptibility. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.08.14.251538. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.14.251538.

Wicik Z, Eyileten C, Jakubik D, Simões SN, Martins DC, Pavão R, et al. ACE2 interaction networks in COVID-19: a physiological framework for prediction of outcome in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.05.13.094714. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.13.094714.

Kemp JR, Unal H, Desnoyer R, Yue H, Bhatnagar A, Karnik SS. Angiotensin II-regulated microRNA 483-3p directly targets multiple components of the renin-angiotensin system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;75:25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.06.008.

Huang Y-F, Zhang Y, Liu C-X, Huang J, Ding G-H. microRNA-125b contributes to high glucose-induced reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis in HK-2 renal tubular epithelial cells by targeting angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:4055–62.

Lambert DW, Lambert LA, Clarke NE, Hooper NM, Porter KE, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is subject to post-transcriptional regulation by miR-421. Clin Sci Lond Engl. 2014;127:243–9.

Marques FZ, Campain AE, Maciej T, Ewa Z-S, Yang Yee Hwa J, Charchar Fadi J, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals renin mRNA overexpression in human hypertensive kidneys and a role for microRNAs. Hypertension. 2011;58:1093–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180729.

Bao H, Gao F, Xie G, Liu Z. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibits apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells during acute lung injury through suppressing MiR-4262. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:759–67. https://doi.org/10.1159/000430393.

Zhang C, Wang J, Ma X, Wang W, Zhao B, Chen Y, et al. ACE2-EPC-EXs protect ageing ECs against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury through the miR-18a/Nox2/ROS pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:1873–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13471.

Sun N-N, Yu C-H, Pan M-X, Zhang Y, Zheng B-J, Yang Q-J, et al. Mir-21 Mediates the inhibitory effect of Ang (1–7) on AngII-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation by targeting Spry1 in lung fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13305-3.

Liu Y, Afzal J, Vakrou S, Greenland GV, Talbot CC, Hebl VB, et al. Differences in microRNA-29 and pro-fibrotic gene expression in mouse and human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2019.00170.

Mallick B, Ghosh Z, Chakrabarti J. MicroRNome analysis unravels the molecular basis of SARS infection in bronchoalveolar stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007837.

B T, T I, C U, R F, M G. Circulating miR-421 targeting leucocytic angiotensin converting enzyme 2 is elevated in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephron. 2019;141. https://doi.org/10.1159/000493805.

Wang H-B, Yang J. The role of renin-angiotensin aldosterone system related micro-ribonucleic acids in hypertension. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1151–5. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.10.12458.

Pierce JB, Simion V, Icli B, Pérez-Cremades D, Cheng HS, Feinberg MW. Computational Analysis of Targeting SARS-CoV-2, Viral Entry Proteins ACE2 and TMPRSS2, and Interferon Genes by Host MicroRNAs. Genes (Basel). 2020;11(11):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111354.

Stelzig KE, Canepa-Escaro F, Schiliro M, Berdnikovs S, Prakash YS, Chiarella SE. Estrogen regulates the expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol - Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;318:L1280–1. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00153.2020.

Bukowska A, Spiller L, Wolke C, Lendeckel U, Weinert S, Hoffmann J, et al. Protective regulation of the ACE2/ACE gene expression by estrogen in human atrial tissue from elderly men. Exp Biol Med Maywood NJ. 2017;242:1412–23.

Kalidhindi RSR, Borkar NA, Ambhore NS, Pabelick CM, Prakash Y, Sathish V. Sex steroids skew ACE2 expression in human airway: a contributing factor to sex differences in COVID-19? Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00391.2020.

Patanavanich R, Glantz SA. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 progression: a meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa082.

Smith JC, Sausville EL, Girish V, Yuan ML, Vasudevan A, John KM, et al. cigarette smoke exposure and inflammatory signaling increase the expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the respiratory tract. Dev Cell. 2020;53:514–529.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.012.

Thul PJ, Åkesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Blal HA, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;356. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3321.

Ferris SP, Kodali VK, Kaufman RJ. Glycoprotein folding and quality-control mechanisms in protein-folding diseases. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:331. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.014589.

Ruggiano A, Foresti O, Carvalho P. Quality control: ER-associated degradation: protein quality control and beyond. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:869. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201312042.

Hua Z, Graham TR. The Golgi Apparatus. Landes Bioscience; 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6268/. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Lumangtad LA, Bell TW. The signal peptide as a new target for drug design. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30:127115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127115.

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Transport from the ER through the Golgi Apparatus. Mol Biol Cell 4th Ed. 2002; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26941/. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Ogunlade B, Guidry JJ, Mukerjee S, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E, Filipeanu CM. The actin bundling protein Fascin-1 as an ACE2-accessory protein. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-020-00951-x.

Sun Z, Ren K, Zhang X, Chen J, Jiang Z, Jiang J, et al. Mass spectrometry analysis of newly emerging coronavirus HCoV-19 spike protein and human ACE2 reveals camouflaging glycans and unique post-translational modifications. Eng Beijing China. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.07.014.

Li W, Zhang C, Sui J, Kuhn JH, Moore MJ, Luo S, et al. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005;24:1634–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600640.

Mehdipour AR, Hummer G. Dual nature of human ACE2 glycosylation in binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike. bioRxiv. 2020;:2020.07.09.193680. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.09.193680.

Zhao X, Guo F, Comunale MA, Mehta A, Sehgal M, Jain P, et al. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum-resident glucosidases impairs severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus NL63 spike protein-mediated entry by altering the glycan processing of angiotensin i-converting enzyme 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:206–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03999-14.

Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, Erickson BR, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-2-69.

Lichtenthaler SF, Lemberg MK, Fluhrer R. Proteolytic ectodomain shedding of membrane proteins in mammals—hardware, concepts, and recent developments. EMBO J. 2018;37. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201899456.

Lambert DW, Yarski M, Warner FJ, Thornhill P, Parkin ET, Smith AI, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30113–9. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M505111200.

Shaltout HA, Figueroa JP, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Alterations in circulatory and renal angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in fetal programmed hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:404–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124339.

Heurich A, Hofmann-Winkler H, Gierer S, Liepold T, Jahn O, Pöhlmann S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J Virol. 2014;88:1293–307. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02202-13.

Matsuyama S, Nagata N, Shirato K, Kawase M, Takeda M, Taguchi F. Efficient activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2. J Virol. 2010;84:12658–64.

Shulla A, Heald-Sargent T, Subramanya G, Zhao J, Perlman S, Gallagher T. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J Virol. 2011;85:873–82.

Deshotels MR, Huijing X, Srinivas S, Eric L, Filipeanu Catalin M. Angiotensin II mediates angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 internalization and degradation through an angiotensin ii type i receptor–dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2014;64:1368–75. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03743.

Wang H, Yang P, Liu K, Guo F, Zhang Y, Zhang G, et al. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008;18:290–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2008.15.

Bayati A, Kumar R, Francis V, McPherson PS. SARS-CoV-2 uses clathrin-mediated endocytosis to gain access into cells. bioRxiv. 2020;:2020.07.13.201509. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.201509.

Zhong J, Basu R, Guo D, Chow FL, Byrns S, Schuster M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 suppresses pathological hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2010;122:717–28 18 p following 728.

Parajuli N, Ramprasath T, Patel VB, Wang W, Putko B, Mori J, et al. Targeting angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as a new therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;92:558–65.

Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8.

Yudong P, Kai M, Hongquan G, Liang L, Ruirui Z, Boyuan W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 112 cardiovascular disease patients infected by 2019-nCoV. Chin J Cardiol. 2020;48:E004. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200220-00105.

Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, Channon KM, Tan PS, Harrison DA, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart. 2020;106:1503–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317393.

Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037.

Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkrüys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:905–913.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.004.

Lutz C, Maher L, Lee C, Kang W. COVID-19 preclinical models: human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Hum Genomics. 2020;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-020-00272-6.

Gurumurthy CB, Quadros RM, Richardson GP, Poluektova LY, Mansour SL, Ohtsuka M. Genetically modified mouse models to help fight COVID-19. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:3777–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-020-00403-2.

Aydemir D, Ulusu NN. Correspondence: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 coated nanoparticles containing respiratory masks, chewing gums and nasal filters may be used for protection against COVID-19 infection. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101697.

de Oliveira RM, Marijanovic Z, Carvalho F, Miltényi GM, Matos JE, Tenreiro S, et al. Impaired proteostasis contributes to renal tubular dysgenesis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020854.

Santhamma KR, Sen I. Specific cellular proteins associate with angiotensin-converting enzyme and regulate its intracellular transport and cleavage-secretion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23253–8.

Danilov SM, Kalinin S, Chen Z, Vinokour EI, Nesterovitch AB, Schwartz DE, et al. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme Gln1069Arg mutation impairs trafficking to the cell surface resulting in selective denaturation of the C-domain. PLoS ONE. 2010;5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010438.

Michaud A, Acharya KR, Masuyer G, Quenech’du N, Gribouval O, Morinière V, et al. Absence of cell surface expression of human ACE leads to perinatal death. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1479–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt535.

Chan KK, Dorosky D, Sharma P, Abbasi SA, Dye JM, Kranz DM, et al. Engineering human ACE2 to optimize binding to the spike protein of SARS coronavirus 2. Science. 2020;369:1261–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by the Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK) through the Abu Dhabi Award for Research Excellence (AARE-2019), United Arab Emirates. Grant number: AARE2019-086.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB conducted the literature and data base searches, wrote the manuscript draft, and prepared the diagrams. BA conceived the idea of the review, refined and edited drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Badawi, S., Ali, B.R. ACE2 Nascence, trafficking, and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: the saga continues. Hum Genomics 15, 8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-021-00304-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-021-00304-9