Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has been one of the most common chronic diseases that create great impacts on both morbidities and mortalities. Many patients who suffering from this disease seek for complementary and alternative medicine. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and related factors of herbal and dietary supplement (HDS) use in patients with DM type 2 at a single university hospital in Thailand.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed in 200 type 2 DM patients via face-to-face structured interviews using developed questionnaires comprised of demographic data, diabetes-specific information, details on HDS use, and medical adherence.

Results

From the endocrinology clinic, 61% of total patients reported HDS exposure and 28% were currently consuming. More than two-thirds of HDS users did not notify their physicians, mainly because of a lack of doctor concern; 73% of cases had no awareness of potential drug-herb interaction. The use of drumstick tree, turmeric and bitter gourd and holy mushroom were most frequently reported. The main reasons for HDS use were friend and relative suggestions and social media. Comparisons of demographic characteristics, medical adherence, and hemoglobin A1c among these non-HDS users, as well as current and former users, were not statistically significantly different.

Conclusions

This study revealed a great number of DM patients interested in HDS use. The use of HDS for glycemic control is an emerging public health concern given the potential adverse effects, drug interactions and benefits associated with its use. Health care professionals should aware of HDS use and hence incorporate this aspect into the clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to various types of medical practices and products apart from currently considered conventional medicine [1]. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the U.S. government’s lead agency for scientific research on CAM, classifies CAM into three subgroups: natural products, mind and body practices, and other approaches such as Ayurvedic medicine and traditional Chinese medicine [1]. The overall use of CAM in the United States has been studied for over a decade by the National Health Interview Survey and has shown a dramatic increase with a maximum of 35% in 2007 [2, 3]. A prevalence of CAM use in diabetes has been analyzed in several studies, and the results were within a range of 34–57% in the United States [4,5,6,7]. The prevalence of CAM use was even as high as 76% in South Asians [8]. Adults who have chronic diseases including diabetes mellitus (DM) tend to use CAM more than healthy people [9,10,11]. In fact, a previous survey reported that adults with diabetes were 1.6 times more likely to use CAM than the non-diabetes population [12]. Biologically based practices such as consumption of herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) were the most widely used modalities of CAM [2, 6, 9, 12]. Previous studies revealed that female gender, higher educational status, duration of disease, and the elderly has a significant association with CAM use in both Western and Asian countries [7, 8, 13]. The major purposes of CAM use were to improve health and well-being or to alleviate undesired symptoms from chronic illness [14, 15]. Interestingly, recommendation by family or friend was the most common reason for CAM use in Thailand [16,17,18]. Many scientific studies have shown the effectiveness of herbal remedies in lowering plasma glucose both in vitro and in vivo [19,20,21]. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial indicated the efficacy of curcumin extract in preventing a progression from prediabetic state to type 2 DM [22]. Despite the growing use of HDS, a well-designed long-term clinical trial on safety and adverse effects has not been established yet [19]. Furthermore, the issue of drug interaction is also unclear [23].

The purpose of the study was to determine the prevalence and pattern of HDS use in type 2 diabetic patients. Demographic characteristics, reasons for HDS usage, frequency of revealed HDS use to physicians, and the relationship between glycemic status and conventional medical adherence with HDS use were extensively explored in this study.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from July through October 2015 using face-to-face structured interviews at the Endocrine Clinic in Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital.

The questionnaire design was developed following a comprehensive literature review of related studies. An initial pilot study was applied to 20 subjects to determine understanding of the questions and validity. The final version of the questionnaire comprised four domains: demographic data, diabetes-specific information, details on HDS use, and conventional anti-diabetic medication adherence (see Additinal file 1). Demographic characteristics included age, gender, hometown, education, employment status, marital status, religion, family type, personal income, exercise, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Diabetes-specific information included duration of DM, presence of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), diabetes- related complications and hospitalizations, other comorbidities, types of conventional anti-diabetic medication, last fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and serum creatinine. HDS usage consisted of type of HDS use, medical purpose, dosage form, duration of HDS use, influencing factors and reasons for HDS use, access to HDS, expense of HDS in Thai bath per month, perception of both positive and negative effect of HDS, awareness of interaction between HDS and conventional medication and disclosure of HDS use to their physicians. The last section assessed the conventional anti-diabetic medication adherence by using the Thai version of the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) in patients with type 2 DM [24]. Respondents were considered as high, medium and low adherence according to an MMAS-8 score of 8, 6 to <8 and <6 points, respectively.

Inclusion criteria were adults aged above 18 years with a previous diagnosis of type 2 DM according to American Diabetes Association criteria [25]. Exclusion criteria were an inability to communicate or give consent, or not currently taking conventional anti-diabetic medication. All included patients were randomly approached to explain the purpose of the study, the procedure and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The participants were given assurance of confidentiality of survey data. Informed consent was obtained from each of the eligible patients. Two authors of this study (P.P. and W.S.), both trained physicians, conducted the face-to-face structured interviews, with an average duration of 15–20 min. Medical records were reviewed in order to validate diabetes-specific information and laboratory investigation results.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk NY, USA). Descriptive analysis was applied to assess prevalence and data related to HDS usage. Data were presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range, IQR), depending on the normality of data. Chi-square tests and ANOVA were used to chart comparisons of demographic data among three assigned subgroups according to HDS use (i.e. never, current and former use). A p-value of 0.05 or less determined statistical significance.

Results

A total of 212 patients were invited to participate in the study. Five patients did not give their consent due to insufficient time, and 7 patients were excluded because of incomplete data. A total of 200 participants were included in the final analysis, 118 (59%) were females. The median age (IQR) was 65 (58–73) years. Among the participants, 69.5% lived in Bangkok and vicinity, 66.5% were retired, 71.5% were married and 93.5% were Buddhist.

Socio-demographic and disease-specific characteristics are displayed in Table 1, which classifies subjects into three groups according to their HDS use, i.e. non-HDS, current and former HDS users. Prevalence of HDS use in this study population was 61%; 56 patients (28%) were currently using HDS. There were no statistically significant differences among these three groups regarding sex, body mass index, education, occupation, monthly income, marital status, family type, smoking and alcohol drinking status. Furthermore, diabetes specific data - including duration of DM, diabetes-related complications, hospitalization due to diabetic emergency, conventional anti-diabetic treatment, SMBG, FPG, HbA1c, serum creatinine and medication adherence – revealed no statistically significant factors associated with HDS use.

Of the 122 patients exposed to HDS, 84 (69%) reported using HDS continuously. The median (IQR) duration of HDS use was 6 (2–12) months. Processed herbs in capsule, tablet or potion form (41.9%) was the most common mode of HDS use. Other forms of HDS use were dried herbs and tea (34.3%) and raw unprocessed herbs (23.8%). As many as 248 types of HDS were found among the 122 patients who reported HDS use. Moringa oleifera Lam. (drumstick tree, 6.9%), Curcuma longa L. (turmeric, 4.9%), Momordica charantia L. (bitter gourd, 4.0%) and Ganoderma lucidum (holy mushroom, 3.6%) were the most commonly used herbs. Table 2 describes the frequency of HDS use among these patients. Surprisingly, nearly 8% of HDS were unknown, as patients were not aware of the ingredients in their HDS products.

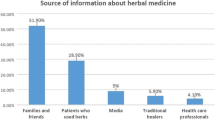

Reasons for HDS use and sources of HDS are shown in Table 3. Friend/family recommendation was the greatest motivation for HDS use, which accounted for nearly 50%. In addition, 13.9% reported that their friends and family also provided HDS for them. Information from the internet and media such as television, radio and social network (21.1%) was the second most influential factor regarding HDS use. Other motives were treatment of a chronic condition (11.2%), perception that HDS were safer than conventional medications (5.6%), disappointment from conventional medicine (4.4%), and promotion of general health and well-being (4.4%). Only 1.2% reported that a health care provider’s recommendation was their reason for HDS use. The majority of patients obtained HDS from a drug store and/or folk remedy shop (36.1%). Markets (17.2%), direct selling (16.4%), and collecting from their own garden were other source of HDS.

If patients take a combination of conventional medication and HDS, awareness of drug-herb interaction and revealing their use to a physician are crucial. Nevertheless, only 7 patients (5.7%) reported an awareness of drug-herb interaction (Table 4). The majority of patients (73%), including both current and former HDS users were unaware of drug-herb interaction. Moreover, 85 out of 122 patients exposed to HDS (69.7%) did not inform their physicians about their use of HDS. The most common reason for their undisclosed use of HDS was that their doctor did not ask (47.1%). Additionally, 32.9% believed that there was no need to inform their physician, and 20% were afraid that their doctor would be against their HDS use.

Sixty-six patients out of a total of 122 patients (54.1%) who were exposed to HDS experienced positive effects from their HDS use. These positive effects were strengthening of the body, improved psychological condition, or relief of severe symptoms. A group of 47 patients (38.5%) reported no change in their health, however, 17 of these patients were continuing to use HDS. In addition, 9 patients (7.4%) suffered from negative effects, including worsening of physical psychological condition. The expense of HDS varied extensively, from obtaining HDS for no cost to spending up to 60,000 Thai baht (approximately 1690 USD; 1 USD = 35.5 Baht). The median (IQR) expenditure for HDS was 300 (100–700) baht.

A comparison between current and former HDS users found that former users were significantly aware of drug- herb interaction compared with current users (X 2 = 6.66, p = 0.036). Additionally, self-reported HDS effects (i.e. no change, positive and negative effects) were significantly difference within those two groups (X 2 = 10.25, p = 0.037). Other comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences.

Discussion

The study showed that 61% of participating DM patients reported exposure to HDS since the time of first diagnosis with DM. This finding was higher than in a previous survey in Thai patients with chronic kidney disease, which found a prevalence of HDS use of 45% [17]. The prevalence of HDS use in other Asian countries, e.g. Sri Lanka (76%), India (67.7%) and Singapore (76%) was estimated to be greater than in the present survey [8, 26, 27]. In contrast, there was less frequent HDS use found in European countries as well as the United States [4,5,6,7, 28, 29]. For example, a survey in Norway reported only 33% HDS use in DM patients [28]. The reason for more commonly use HDS in Asian countries could be due to cultural perception of HDS.

These study findings revealed extremely varied types of HDS use. The most frequently used are Moringa oleifera Lam (6.9%), Curcuma longa L. (4.9%) and Momordica charantia L. (4%). Moringa oleifera was proved anti-hyperglycemic properties by lowering FPG and HbA1c in both animal studies [30, 31] and human studies [32, 33]. Curcuma longa L., generally known as turmeric, is also an abundantly used HDS. Several studies reported anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperglycemic effects of Curcuma longa L. by down-regulating inflammatory cytokines [34,35,36]. Furthermore, it also prevents development of DM in prediabetic individuals [22]. Nevertheless, there have been only a limited numbers of studies on the adverse effects and toxicities of these herbs, thus demanding an urgent need to explore the safety issues [37].

From our study, processed herbs in capsule, tablet or potion form was the most frequent mode of HDS use (41.9%). Qualified preparation processes of these products are uncertain. Therefore, contamination and adulteration are of immense concern, as many studies have reported [38,39,40]. Dust, pollen, microbes, pesticides, toxic heavy metals and even prescription drugs were found in herbal medicinal products and caused adverse reactions [40]. In addition, of the 248 types of HDS, 19 (7.7%) were noted as unknown kinds of herbs, which leads to difficulty in monitoring toxicity and interaction between herbs and conventional medicine.

Recommendation by friends and family had the most influence (49%) on HDS use in our study. This finding is comparable with previous studies, which showed a significant impact from friends and families on HDS use [17, 18, 41]. As the internet and social media have become easy accessible nowadays, this inevitably affects the perception and knowledge of patients about disease and management [42, 43]. We found that 21.1% of the reported reasons for HDS use was information from media and the internet. We believe that the internet will become an even more extensive source of information for chronic disease patients especially DM [43]. Hence, there should be a policy for providing scientific evidence-based health information on the internet. Moreover, health care providers, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists and dietitians should update their clinical knowledge about HDS, as well as be prepared to discuss HDS effects and acknowledge adverse effects with patients.

Although the prevalence of HDS use is high, as few as 30% of patients revealed their HDS use to physicians. The primary reason for undisclosed HDS use was unawareness of this concern. Additionally, over 70% of participants exposed to HDS had no awareness of drug-herb interactions [44]. As HDS use becomes more popular, physicians should consider HDS intake to be equally as important as that of conventional medication. Our study found no statistically significant difference in any of demographic characteristic, so it may be impossible to predict the use of HDS. Thus, physicians should routinely obtain a patient’s history use of HDS, as well as screen for potential adverse effects [45].

There are a number of limitations in our study. First of all, the present study was based on patient-reported information; therefore, recall bias could occur. Secondly, this study was conducted in a specialty clinic and thus may not represent the general population, including individuals with no access to conventional medicine. Further studies should be conducted in order to estimate the impact of HDS on a national level. Continued research regarding the efficacy and safety of HDS is needed.

Conclusions

The prevalence of HDS use in DM patients is high and can be underestimated by physicians due to undisclosed use. DM patients obtained information about HDS from their friends and family as well as the internet and other media. There should be some interventions to guide the way for evidence-based and safe HDS use. Importantly, physicians should seriously consider HDS use in DM patients and always take a complete history of HDS use.

References

National Center for Complementary and Integrative health, National Institutes of Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's In a Name? 2016. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health. Accessed 24 May 2017.

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States. Natl Health Stat Report. 2002-2012;2015:1–16.

Wu CH, Wang CC, Tsai MT, Huang WT, Kennedy J. Trend and pattern of herb and supplement use in the United States: results from the 2002, 2007, and 2012 national health interview surveys. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:872320.

Bell RA, Suerken CK, Grzywacz JG, Lang W, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults with diabetes in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 2006;12:16–22.

Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among persons with diabetes mellitus: results of a national survey. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1648–52.

Garrow D, Egede LE. National patterns and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use in adults with diabetes. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:895–902.

Garrow D, Egede LE. Association between complementary and alternative medicine use, preventive care practices, and use of conventional medical services among adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:15–9.

Medagama AB, Bandara R, Abeysekera RA, Imbulpitiya B, Pushpakumari T. Use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) among type 2 diabetes patients in Sri Lanka: a cross sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14

Saydah SH, Eberhardt MS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:805–12.

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75.

Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–53.

Egede LE, Ye X, Zheng D, Silverstein MD. The prevalence and pattern of complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:324–9.

Ceylan S, Azal O, Taslipinar A, Turker T, Acikel CH, Gulec M. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Turkish diabetes patients. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17:78–83.

McCaffrey AM, Pugh GF, O'Connor BB. Understanding patient preference for integrative medical care: results from patient focus groups. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1500–5.

Nahin RL, Byrd-Clark D, Stussman BJ, Kalyanaraman N. Disease severity is associated with the use of complementary medicine to treat or manage type-2 diabetes: data from the 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:193.

Moolasarn S, Sripa S, Kuessirikiet V, Sutawee K, Huasary J, Chaisila C, et al. Usage of and cost of complementary/alternative medicine in diabetic patients. J Med Assoc Thail. 2005;88:1630–7.

Tangkiatkumjai M, Boardman H, Praditpornsilpa K, Walker DM. Prevalence of herbal and dietary supplement usage in Thai outpatients with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:153.

Tangkiatkumjai M, Boardman H, Praditpornsilpa K, Walker DM. Reasons why Thai patients with chronic kidney disease use or do not use herbal and dietary supplements. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:473.

Medagama AB, Bandara R. The use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: is continued use safe and effective? Nutr J. 2014;13:102.

Al-Malki AL, El Rabey HA. The antidiabetic effect of low doses of Moringa oleifera Lam seeds on streptozotocin induced diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in male rats. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:381040.

Rungseesantivanon S, Thenchaisri N, Ruangvejvorachai P, Patumraj S. Curcumin supplementation could improve diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction associated with decreased vascular superoxide production and PKC inhibition. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:57.

Chuengsamarn S, Rattanamongkolgul S, Luechapudiporn R, Phisalaphong C, Jirawatnotai S. Curcumin extract for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2121–7.

Prabhakar PK, Kumar A, Doble M. Combination therapy: a new strategy to manage diabetes and its complications. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:123–30.

Sakthong P, Chabunthom R, Charoenvisuthiwongs R. Psychometric properties of the Thai version of the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:950–7.

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S11-S24.

Kumar D, Bajaj S, Mehrotra R. Knowledge, attitude and practice of complementary and alternative medicines for diabetes. Public Health. 2006;120:705–11.

Lim MK, Sadarangani P, Chan HL, Heng JY. Complementary and alternative medicine use in multiracial Singapore. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13:16–24.

Kristoffersen AE, Stub T, Salamonsen A, Musial F, Hamberg K. Gender differences in prevalence and associations for use of CAM in a large population study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:463.

Weidenhammer W, Lacruz ME, Emeny RT, Linde K, Peters A, Thorand B, et al. Prevalence of use and level of awareness of CAM in older people - results from the KORA-age study. Forsch Komplementmed. 2014;21:294–301.

Abdull Razis AF, Ibrahim MD, Kntayya SB. Health benefits of Moringa Oleifera. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8571–6.

Kar A, Choudhary BK, Bandyopadhyay NG. Comparative evaluation of hypoglycaemic activity of some Indian medicinal plants in alloxan diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:105–8.

Stohs SJ, Hartman MJ. Review of the safety and efficacy of Moringa Oleifera. Phytother Res. 2015;29:796–804.

Mbikay M. Therapeutic potential of Moringa Oleifera leaves in chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:24.

Maradana MR, Thomas R, O'Sullivan BJ. Targeted delivery of curcumin for treating type 2 diabetes. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:1550–6.

Lao CD, Ruffin MT 4th, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM, et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:10.

Srinivasan M. Effect of curcumin on blood sugar as seen in a diabetic subject. Indian J Med Sci. 1972;26:269–70.

Fischer FH, Lewith G, Witt CM, Linde K, von Ammon K, Cardini F, et al. High prevalence but limited evidence in complementary and alternative medicine: guidelines for future research. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:46.

Ching CK, Lam YH, Chan AY, Mak TW. Adulteration of herbal antidiabetic products with undeclared pharmaceuticals: a case series in Hong Kong. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:795–800.

Ernst E. Adulteration of Chinese herbal medicines with synthetic drugs: a systematic review. J Intern Med. 2002;252:107–13.

Posadzki P, Watson L, Ernst E. Contamination and adulteration of herbal medicinal products (HMPs): an overview of systematic reviews. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:295–307.

Naja F, Mousa D, Alameddine M, Shoaib H, Itani L, Mourad Y. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use among diabetic patients in Beirut. Lebanon: a cross-sectional study BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:185.

Chretien KC, Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;127:1413–21.

Greene JA, Choudhry NK, Kilabuk E, Shrank WH. Online social networking by patients with diabetes: a qualitative evaluation of communication with Facebook. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:287–92.

Zablocka-Slowinska K, Dzielska E, Gryszkin I, Grajeta H. Dietary supplementation during diabetes therapy and the potential risk of interactions. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2014;23:939–46.

Frenkel MA, Borkan JM. An approach for integrating complementary-alternative medicine into primary care. Fam Pract. 2003;20:324–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor Supanee Thanakun, Department of Oral Medicine and Periodontology, Faculty of Dentistry, Mahidol University, for valuable help with data analysis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study. PP and WS gathered and analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Herbal and dietary supplements use in DM: Questionnaires. (DOCX 507 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Putthapiban, P., Sukhumthammarat, W. & Sriphrapradang, C. Concealed use of herbal and dietary supplements among Thai patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord 16, 36 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0317-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0317-3