Abstract

Background

Preclinical and clinical evidence supports the concept of bidirectional brain-gut microbiome interactions. We aimed to determine if subgroups of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) subjects can be identified based on differences in gut microbial composition, and if there are correlations between gut microbial measures and structural brain signatures in IBS.

Methods

Behavioral measures, stool samples, and structural brain images were collected from 29 adult IBS and 23 healthy control subjects (HCs). 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing was used to profile stool microbial communities, and various multivariate analysis approaches were used to quantitate microbial composition, abundance, and diversity. The metagenomic content of samples was inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequence data using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt). T1-weighted brain images were acquired on a Siemens Allegra 3T scanner, and morphological measures were computed for 165 brain regions.

Results

Using unweighted Unifrac distances with hierarchical clustering on microbial data, samples were clustered into two IBS subgroups within the IBS population (IBS1 (n = 13) and HC-like IBS (n = 16)) and HCs (n = 23) (AUROC = 0.96, sensitivity 0.95, specificity 0.67). A Random Forest classifier provided further support for the differentiation of IBS1 and HC groups. Microbes belonging to the genera Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Bacteroides contributed to this subclassification. Clinical features distinguishing the groups included a history of early life trauma and duration of symptoms (greater in IBS1), but not self-reported bowel habits, anxiety, depression, or medication use. Gut microbial composition correlated with structural measures of brain regions including sensory- and salience-related regions, and with a history of early life trauma.

Conclusions

The results confirm previous reports of gut microbiome-based IBS subgroups and identify for the first time brain structural alterations associated with these subgroups. They provide preliminary evidence for the involvement of specific microbes and their predicted metabolites in these correlations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alterations in gut microbial composition or “dysbiosis” have been implicated in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [1,2,3]. IBS is the most common chronic visceral pain syndrome. In the absence of agreed upon biomarkers, the syndrome is defined by symptom criteria which include the presence of chronically recurrent abdominal pain associated with alterations in bowel habits [4]. This hypothesis has been based on the reported findings of gut microbial differences between healthy control subjects (HCs) and IBS patients, on findings in rodent models of IBS, and on the theoretical appeal of such a hypothesis to explain various clinical observations. These include the observations in some patients that antibiotic treatment can both trigger and attenuate IBS symptoms [2], the development of IBS-like symptoms following gastroenteritis in a small percentage of patients [5], and the beneficial effects of the fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) elimination diet and probiotic ingestion [2]. In addition, the well described interactions between the gut microbiota with the brain and the gut-based immune system provide plausible mechanisms consistent with a role of altered gut microbiota in IBS [6]. However, to date, few consistent differences have been identified in the gut microbiota between HCs and IBS. This may be in part related to the clinical (age, sex, medications) and physiological (intestinal transit, history of early adverse life events [EALs], stress reactivity) heterogeneity of patients selected solely by symptom criteria. One exception is an increased ratio between the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (F-B ratio) which has been reported by several investigators [7,8,9,10]. A recent study provided evidence for subgroups of IBS patients based on gut microbial composition, which were independent of predominant bowel habits and established symptoms criteria [10].

There is a growing consensus that alterations in the bidirectional interactions of the central nervous system with the gut (brain-gut axis) play an important role in IBS pathophysiology (reviewed in [6]). In animal models, early adverse life events have been shown to be associated with stress-induced alterations in intestinal transit (indexed by increased fecal pellet output, [11] and in the composition of the gut microbiota [12, 13]. In addition to a growing list of abnormalities described by different investigators in the different components of the peripheral gut connectome [14, 15], both structural and functional alterations of the brain have been identified in IBS subjects [16]. Recent analyses have identified widespread gray and white matter alterations in the brain of IBS patients, including extensive changes in the somatosensory system (thalamus, basal ganglia, S1, and M1). A history of early adversity has also been shown to be correlated with brain structural changes [17]. A recent study showed cross sectional correlations between brain structure and gut microbial composition [18]. The fact that functional activity in some of the same regions (somatosensory regions, basal ganglia) was increased when healthy women consumed a probiotic mix over 4 weeks [19] suggests the possibility of a link between gut microbial composition and sensory processing and integration in the brain, both in healthy control subjects (HCs) and in a subgroup of IBS patients.

By studying a group of well phenotyped IBS subjects and HCs, we aimed to address three questions related to gut microbiota, clinical parameters, and brain signatures: 1. Can gut microbial composition be used to classify IBS patients and to identify subgroups with different clinical and behavioral symptoms, as recently suggested? 2. Is there an association between a history of early adverse life events (EALs) and gut microbial composition? 3. Is there a relationship between gut microbial composition and IBS-related brain biomarkers? Based on past clinical literature and brain regions altered in IBS, we expected to see a relationship between microbiota and emotion-related (amygdala, hippocampus) and sensory brain regions (basal ganglia, posterior insula, and primary sensory and motor regions).

Methods

Participants

Stool samples were collected at UCLA from 29 right-handed adult IBS patients (22 females) and 23 HCs (14 females), who also underwent multimodal brain imaging studies at UCLA. IBS subjects met Rome III symptom criteria for IBS [20]. A gastroenterologist or nurse practitioner obtained a medical history and physical exam to confirm the IBS diagnosis. IBS patients with any bowel habit were included. With regard to IBS diagnostic subtypes, 11 subjects had IBS-constipation, 10 subjects had IBS-diarrhea, and 8 subjects had either alternating (1), mixed (5), or unspecified (2) bowel habits. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview was used to identify past or current psychiatric illness [21].

Exclusionary criteria for all subjects included (1) serious medical conditions or were taking medications which could compromise interpretation of the brain imaging; (2) ongoing major psychiatric diagnoses or use of psychotropic medications in the past 6 months (subjects were not excluded for lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorders or for intake of low-dose tricyclic antidepressants for non-psychiatric indications); (3) use of antibiotics in the past 3 months, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opioids; and (4) excessive physical exercise (e.g., marathon runners). All procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at our institution. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Questionnaires

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADs] [22] and the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 [PHQ] were obtained to assess mood [23]. The Early Traumatic Inventory–Self Report (ETI-SR) [24] was used to access histories of childhood traumatic and adverse life events that occurred before the age of 18 years old and covers four domains: general trauma (31 items), physical (9 items), emotional (7 items), and sexual abuse (15 items) [24]. The Catastrophizing subscale from the Coping Strategies Questionnaire was administered to assess levels of catastrophizing [25]. The degree to which subject viewed situations as stressful in the past month was measured by the Perceived Stress Scale [26]. Medication usage was defined by endorsement of any of the following: antispasmodic, laxatives, stool_softener, fiber supplement, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, acetaminophen, thyroid medications, antihistamine, or proton pump inhibitors.

A 1-month qualitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III)1 was used to collect information on participants’ eating patterns. The FFQ data was processed using the National Cancer Institute’s Diet*Calc software (Diet*Calc Analysis Program, Version 1.4.3. National Cancer Institute, Applied Research Program. November 2005.), which provides estimates of energy and nutrient intake [27]. A participant’s total animal fat intake was calculated by summing the total fat (in grams) of foods containing animal sources of fat (Additional file 1: Table S1). Combination foods such as soups and casseroles were excluded due to inability to differentiate animal and plant fat sources. Using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), the mean intake of animal fat was calculated for each group and compared across the three groups using univariate analysis of variance.

Neuroimaging, segmentation, and parcellation

T1-weighted images were acquired on a Siemens Allegra 3 Tesla scanner, repetition time = 2200 ms, echo time = 2.85 s, inversion time = 750 ms, flip angle = 20°, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, resolution = 256 × 256, slices per volume = 176, slice thickness = 1 mm, voxel size = 0.86 × 0.86 × 1 mm. T1-image segmentation and regional parcellation were conducted using FreeSurfer [28,29,30] following the nomenclature described in the Destrieux and Harvard-Oxford subcortical atlas [31, 32]. For each cerebral hemisphere, a set of 74 cortical structures were labeled in addition to 7 subcortical structures and to the cerebellum. One additional midline structure (the brain stem) was also included, for a complete set of 165 parcellations for the entire brain. Four representative but distinct morphological measures were computed for each cortical parcellation: gray matter volume, surface area, cortical thickness, and mean curvature. A list of all the regions is provided in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Microbial analysis

Intestinal microbial composition: stool collection, processing, and analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing data

Stool specimens were stored in an RNA stabilizing reagent (RNALater) at −80 °C following collection at UCLA. They were later placed in cryo-containers and shipped to the Texas Children’s Microbiome Center. Bacterial DNA from the self-collected stool specimens was extracted, amplified, and sequenced, as previously described.[9, 33,34,35] Briefly, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequence libraries were generated using the V3-V5 (357F/926R) primer region [9, 36] and sequenced on the 454 platform (Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA). The sequence libraries were parsed by barcode and quality filtered using the Genboree Microbiome Toolset [35], where sequences shorter than 200 bp, having average quality scores <20, containing ambiguous base calls, or including mismatches to barcode or sequencing primer were culled. After quality filtering and the removal of barcode and primer sequences, all remaining sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity level using QIIME (Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology, v1.3.0) [37]. OTUs were clustered using the CD-Hit algorithm [38], and reads were screened for chimeras using ChimeraSlayer [39]. All potential chimeras were excluded from further analysis. OTU identities were assigned using the Ribosomal Database Project Classifier [40] with the Greengenes reference database (version 12-10) and confidence scores ≥80%. To accommodate for variance in sequencing depth, all sequence libraries were randomly sub-sampled to a depth of 1355 sequences, the size of the smallest quality filtered sequence library, prior to downstream analysis. Bacterial community profiles were analyzed by global parameters (described below) including determination of diversity, evenness, richness, and relative abundance of the bacteria identified in each sample. Output sequences were classified at the domain, phylum, family, genus, and species levels where possible, depending on the depth of reliable classifier assignments [41].

Diversity analysis

Alpha-diversity metrics (i.e., bacterial diversity within a sample) were computed and included Faith’s phylogenetic diversity metric, chao1 richness estimator, Shannon’s entropy, and counts of observed OTUs [42, 43]. Between-group differences in alpha diversity were evaluated using a nonparametric t test, and 1000 Monte Carlo permutations were used to calculate the nonparametric p value. In addition, for each group, alpha-diversity curves were generated for each diversity metric at different rarefaction depths.

Determining relationships among samples

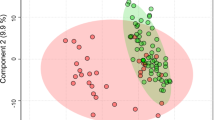

A phylogenetically informed distance matrix was computed using the unweighted UniFrac metric [44]. Hierarchical clustering using average linkage was performed to visualize relationships among the samples based on similarity of microbial composition. As recommended by Navas-Molina et al. [42], principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to evaluate the presence of clusters or groupings in the data. PCoA provides information regarding the largest source of variation in the data and allows the observation of similarities and differences between samples. Pearson correlations of OTU relative abundance versus principal coordinate axis scores were used to identify taxa contributing to the separation of samples in PCoA space. PCoA indicated the presence of three groups having similar microbial profiles, and these are labeled as HCs, HC-like IBS, and IBS1 throughout the manuscript.

Adonis analysis, a permutational analysis of variance, was performed to test for differences between groups in overall microbial composition [45].

Random forest analysis was used to evaluate the degree to which fecal communities could classify group and identify features differentiating IBS microbial communities from controls. The caret package (version 6.0-73) for R [46] was used with repeated cross-validation (10-fold, five repeats). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the ROC (AUROC) were calculated using the pROC package for R (version 1.8) [47]. Any OTU occurring in fewer than 10% of subjects was filtered prior to implementing the random forest algorithm.

Group differences in taxonomic abundance and clinical metadata

Group differences in relative abundance at each taxonomic level (phylum, class, order, family, genus, and OTUs/“species”) and the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes were tested using the nonparametric Kruskal Wallis test correcting for multiple comparisons with the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure and confirmed using pairwise comparisons. FDR correct p values (q) are reported. Independent sample t tests were used to test for group differences in groups on symptom severity, mood, and emotional trauma scores.

Association between brain structure and microbiota

Using Matlab, partial correlational analysis controlling for total gray matter volume was used to examine the association between the relative abundance of the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes showing group differences and all 165 brain volumes in IBS (n = 29). We also tested for differences in the brain morphometry of somatosensory-, motor-, and emotional-related regions between the microbiota-derived clusters, IBS1, HC-like IBS, and HC using contrast analysis within the framework of the general linear model. Group was specified as a factor, and total gray matter volume was specified as a covariate. Somatosensory and motor regions included the basal ganglia (putamen, caudate nucleus, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus), primary sensory (postcentral gyrus, postcentral sulcus, central sulcus), secondary sensory (subcentral gyrus (central operculum) and sulci), motor (precentral gyrus, inferior part of the precentral sulcus, superior part of the precentral sulcus), and mid and posterior insula (long insular gyrus and central sulcus of the insula, inferior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula, posterior ramus of the lateral sulcus) regions. Emotional-related regions included the amygdala and the hippocampus. Analyses examining the relationship between brain structure and microbiota analyses were considered exploratory and important for future hypotheses generation. We report uncorrected p values as Type II error control and is equally important in exploratory research. We caution against reliance on significance testing and instead emphasize interpretation of effect sizes of brain-microbiota associations for future studies.

Predicted metagenomics analysis

The metagenomic content of samples was inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequence data using PICRUSt 1.0 and the KEGG database, which includes 6909 bacterial genes (i.e., metagenes) annotated in reference genomes [48]. The data were filtered to remove metagenes present in less than five samples or with an overall abundance less than 10−6. Group differences in predicted metagenes were identified using DESeq2 in R, which employs an empirical Bayesian approach to shrink dispersion and fit non-rarified count data to a negative binomial model [49]. P values were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure. DESeq2 was also employed to identify metagenes with a statistically significant association with brain structural features that differed among the three microbial clusters. Selected metagenes associated with brain morphometry and microbiome clusters were further analyzed with FishTaco (http://borenstein-lab.github.io/fishtaco) [50]. This method uses a permutation approach and Shapley value analysis to quantitate the contribution of individual taxa to shifts in metagene abundance between two clusters (https://borenstein-lab.github.io/fishtaco/). Bioinformatics is available as Additional file 3.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The means and standard deviation for descriptive data describing the samples can be found in Table 1. The average ages for IBS (n = 29, females = 21) and HCs (n = 23, females = 14) were similar, 26.1 years (SD = ±5.72 and 26.0 years (±6.5), respectively. Average symptom duration in IBS subjects was 11.3 (±13.2) years. Even though IBS subjects as a group had significantly greater level of anxiety (p = .03) but not depression symptoms, the anxiety levels for the majority of subjects were within the normal range. However, six IBS subjects (HAD score range 12–17) and one HC (HAD score 13) had scores greater than 11, indicating a probable level of clinical anxiety. Compared to HCs, IBS reported greater levels of perceived stress (p = .02) and higher levels of catastrophizing (p = .02). No group differences were observed in total emotional trauma history scores, but there was a trend for a greater history of emotional trauma in IBS (p = .09). Moderate to high levels of early life trauma (4–5) on the emotional subscale were reported by 36% IBS subjects while no healthy control subjects showed such scores. IBS subjects reported average of overall symptoms in the past week of 9.3 (±4.3) on a 21-point numeric rating scale (0 = no pain, 20 = the most intense symptoms imaginable). Distribution of bowel habit was 11 constipation (37.9%), 10 diarrhea (34.5%), 1 alternating (3.4%), 5 mixed (17.2%), and 2 unspecified (6.9%].

No statistically significant differences in dietary patterns were observed between groups. IBS1 showed slightly higher BMI than HC-like IBS (p = .047) although both groups had an average body weight within the normal range.

IBS subgroup identified based on a microbiome signature

Hierarchical clustering using average linkage and PCoA analysis on unweighted Unifrac distances are depicted in Fig. 1a, b and Additional file 4: Figure S1. Together, these analyses indicated that microbial signatures could be used to group patients and to discriminate among samples. Based on the PCOA and hierarchical clustering, the samples were labeled as IBS1 (IBS patients with microbial profiles distinct from HCs; n = 13), HC-like IBS (IBS patients with similar microbial composition as HCs; n = 16) and HCs (n = 23). One IBS subject clustered with IBS1 in the PCoA but clustered with HCs in the hierarchical clustering. This subject was labeled as HC-like IBS subject. We tested whether this group assignment changed group difference or correlation results but it did not. Adonis analysis [45] of the unweighted Unifrac distances indicated that a significant proportion of the variance could be explained by IBS1–HC differences F(1,51) = 5.79, p = .004, R 2 = .10. The variance accounted for other group contrasts was not statistically significant (HC-like IBS-IBS1, F(1,51) = 2.2, p = .073, R 2 = .04; HC-like IBS-HCs, F(1,51) = 1.23, p = .25, R 2 = .02).

16s rRNA gene data revealed two distinct IBS subgroups, one indistinguishable from healthy controls. a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) on the unweighted Unifrac distance matrix from the rarefied data was used to evaluate the presence of clusters or groupings based upon operational taxonomic unit (OTU)-level microbial features. b Hierarchical clustering using average linkage was performed to visualize relationships among the samples based on similarity of microbial composition. Both procedures operate on a phylogenetically informed distance matrix computed using the unweighted UniFrac metric

OTUs contributing to the variation in microbial signatures along the 3rd axis of the PCoA plot (i.e., that which captured the separation of the IBS1 communities from the HC and HC-like IBS communities) were identified using correlation analysis. Those whose relative abundances correlated most strongly with the location along this axis are provided in Additional file 5: Table S3 and included members of the genera Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, and Blautia.

Random forest analysis provided further support for the differentiation of IBS1 and HC groups. This analysis identified an OTU-based signature which correctly distinguished the majority of IBS1 subjects from HC subjects. Using 10-fold cross-validation, the resulting model had an AUROC of 0.96, sensitivity of 0.95, and specificity of 0.67 (Additional file 6: Figure S2). OTUs contributing to the differentiation of IBS1 and HC gut communities, according to their random forest importance (i.e., mean decrease in accuracy) scores, included members of the genera Blautia, Streptococcus, Faecalibacterium, and Bacteroides (see Additional file 7: Table S4).

Diversity analyses and comparison of bacterial relative abundances among IBS subgroups

Alpha diversity by groups (HC, IBS) and subgroups (IBS1, HC-like IBS, HC) were calculated, and results are depicted in Additional file 8: Figure S3. Comparison of Faith’s phylogenetic diversity indices with nonparametric t tests indicated that as a group, all IBS subjects (n = 29) showed significantly greater diversity than HCs, t(50) = 2.83, p = .007. Examining the IBS subgroups indicated this was largely due to the fact that the IBS1 community was more diverse than the HC-like IBS patients, t(27) = 3.33, p = .012, and HCs, t(36) = 3.80, p = .003. There were no differences observed between the HC-like IBS subjects and HCs, t = .90, p = .99. Similar results were observed for the other diversity measures: chao1 richness estimator, Shannon’s entropy, and number of observed OTUs.

Figures 2 and 3 depict the microbial composition of each group and individual at the phylum and class levels. The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F-B ratio) was significantly higher in the IBS1 subgroup compared to HCs (q = .02). The F-B ratio in the HC-like IBS group did not differ significantly from either group (Fig. 4a).

Group differences in the relative abundance of microbiota. Bar graphs depict the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (a), the mean relative abundance for identifiable operational taxonomic units (b), and taxa demonstrating group differences at each taxonomic level (phylum, class, order, family, and genus (c-f)). Error bars represent standard deviations

The relative abundances of OTUs and the mean relative abundance for identifiable taxa demonstrating overall group differences at each taxonomic level (phylum, class, order, family, and genus) are depicted in Fig. 4. The means and standard deviations as well as Kruskall Wallis tests of significance can be found for identifiable and unidentified taxa and OTUs in Additional file 9: Table S5.

At the phylum level (Fig. 4c), the relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly greater in the IBS1 subjects compared to HCs (q = .002) but not the HC-like IBS subjects (q = .075). On the other hand, the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was significantly lower in IBS1 group compared to HCs (q = .003) but not in the HC-like IBS subjects (q = .12). For all comparisons, the HC-like IBS group did not differ from the HCs with respect to the relative abundance of either Firmicutes or Bacteroidetes. Furthermore, no differences were observed at the phylum level for the relative abundance of Actinobacteria (IBS1 .1%, HC-like IBS 0%, and HCs 0%) or Proteobacteria (1.3, .8, .4%).

At the class level (Fig. 4d), differences were observed in the Firmicutes classes, Bacilli and Clostridia. The relative abundance of members of Bacilli was greater in IBS1 compared to HC-like IBS (q = .001) and HCs (q = .005). For Clostridia, IBS1 showed greater abundances than HCs (q = .004) but not HC-like IBS (q = .14). IBS1 had lower abundances of Bacteroidetes class Bacteroidia compared to HCs (q = .002) but not HC-like IBS (q = .075).

At the order level (Fig. 4e), differences were observed with respect to the Bacilli order Lactobacillales with greater abundance observed for IBS1 compared to HC-Like IBS (q = .004) and HCs (q = .004). The relative abundance of Bacteroidales order was lower in IBS1 compared to HCs (q = .002) but not HC-like IBS (q = .075).

At the genus level (Fig. 4f), members of the Erysipelotrichaceae genus Holdemania were more abundant among IBS1 compared to HC-like IBS (q < .001) and HCs (q < .001). Members of the Porphyromonadaceae genus Parabacteroides were less abundant in IBS1 compared to HCs (q = .003) but not HC-like IBS (q = .097).

Mean differences in clinical metadata between IBS subgroups based on microbial clusters

Detailed clinical data for the subgroups of IBS based on microbial community profiles, IBS1 (9 females, 5 males) and HC-like IBS (12 females, 3 males), are available in Additional file 10: Table S6. IBS1 subjects reported a longer duration of symptoms than HC-like IBS (t(26) = 2.80, p = .01) as well as higher scores on the ETI emotional subscale, t(25) = 3.14, p = .004. Although overweight status (BMI >25.0) was not significantly different between the two IBS clusters, IBS1 [m(sd), 25.52 (5.68)] showed a trend (t(27) = 1,99, p = .057) toward greater BMI compared to HC-like IBS [20.99 (6.51)], Hedge’s effect size g (Cohen’s d corrected for small sample sizes) = .74. This was associated with a trend for higher dietary plant fat intake in the IBS1 group compared to HC-like IBS (p = .047) and HC (p = .017).

In contrast, microbial community clustering in IBS was not associated with sequencing depth, age, predominant bowel habit, symptoms of anxiety or depression, levels of catastrophizing, perceived stress, or medication usage.

Subgroup analysis in only females indicated that the mean differences in the duration of symptoms, t(19) = 2.72, p = .014, and emotional ETI scores remained significant as did the trend for greater BMI (t(19) 1.80, p = .08 in IBS.

Associations between clinical metadata and microbiota taxa differentiating IBS1 from HC-like IBS and HCs

Order level taxa

In IBS subjects, Lactobacillales, which had significantly higher abundance in IBS1, had a moderately positive correlation with ETI total score (r = .51, p = .008), as well as sexual (r = .59, p = .001), physical (r = .51, p = .007), and emotional (r = .42, p = .028) subscores. No correlations were observed for Bacteroidales. Examining correlations in female IBS only revealed that Bacteroidales positively correlated with overall symptom severity (r = .423, p = .056). Correlations with the ETI total score (r = .56, p = .01), and its physical (r = .53, p = .013), emotional (r = .52, p = .02), and sexual (r = .58, p = .008) subscores persisted.

Genus level taxa

Abundance of Parabacteroides was positively associated with bloating r = .48 p = .03. Because Holdemania was not identified in any group but IBS1, associations with this genus were not examined.

Across all subjects (n = 48), the relative abundance of the Firmicutes-associated class Bacilli was positively correlated with ETI total score (r = .34, p = .018) as well as with sexual (r = .43, p = .002) and emotional (r = .38, p = .007) subscores. No correlations with EALs were found for the Firmicutes-associated class Clostridia or the Bacteroidetes-associated class Bacteroidia. IBS1 had greater scores on the emotional scale of the ETI than HC-like IBS (p = .004) and HCs (p = .001), while no differences were observed between IBS and HCs as a group for this score.

Association between brain structure and discriminative microbiota in IBS subjects

Table 2 shows the results of the correlations between the relative abundance of classes of bacteria associated with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes that discriminated the microbial subgroups (Fig. 4d) and the parcellated 165 regional brain volumes for all IBS (n = 29). Moderately sized correlations were observed for the Clostridia belonging to phylum Firmicutes (higher in IBS1), and for the Bacteroidia belonging to phylum Bacteroidetes (lower in IBS1) with several sensory integration regions including the thalamus, basal ganglia (caudate nucleus, putamen, pallidum, nucleus accumbens), and the superior part of the precentral gyrus (motor cortex). Similar correlations were found for the anterior insula and ventral prefrontal regions.

Based on the relative abundance of these classes of bacteria, volumes in the sensory brain regions were increased, while volumes of insula and prefrontal cortices were decreased in IBS1 compared to HC-like IBS. Very few correlations were observed for the parietal, occipital, and temporal regions. The abundance of the Bacilli belonging to phylum Firmicutes showed correlations with the volume of fewer regions including the nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortices, and ventral posterior cingulate cortex.

As can be seen in Table 3, compared to HC-like IBS and HCs, IBS1 had smaller cortical thickness and larger surface area in the anterior insula. Compared to HC-like IBS, IBS1 also showed greater volume and surface area in the posterior insula, right globus pallidum, and lower cortical thickness and surface area of motor cortex. Finally, compared to HCs, IBS has greater volume in the mid/posterior insula.

Compared to HCs, HC-like IBS had greater cortical thickness in the sensory brain regions, including the left post central and central sulci and the right posterior insula.

Metagenes enriched in the IBS1 subgroup are associated with posterior insula morphometry

We investigated on an exploratory basis whether the distinct microbial composition of IBS1 compared to HC-IBS and HC was associated with a shift in the functional profile of the microbiome. This was motivated by the possibility that altered bacterial production of neuroactive metabolites could contribute to the association of microbial clusters with brain morphometric parameters. Counts of bacterial genes (metagenes) were predicted from the 16S rRNA gene sequence data using PICRUSt, which imputes gene content for each OTU based upon the phylogenetically closest reference genome. The resulting count data were fitted to negative binomial models using DESeq2 with microbial cluster as a predictor. In pairwise comparisons, 606 metagenes (i.e., bacterial genes predicted by PICRUSt) differed in abundance between the IBS1 subgroup and HC-IBS with adjusted p value <.05 and 1223 metagenes differed between IBS1 and HC. In contrast, there were no differential metagenes between HC-IBS and HC. In parallel analyses, the same methodology was used to identify metagenes associated with the 10 brain morphometric parameters (each analyzed separately) that differed among the three microbial clusters at p < .01 (Table 3). Twenty-seven metagenes were found that were significantly associated with both the IBS1 subgroup and with brain morphometric parameters, including 20 that were associated with the surface area of the right inferior segment of the inferior segment of the circular sulcus (a region of the posterior insula) (Additional file 11: Table S7). Of these, we focused on two metagenes enriched in IBS1 that are involved in neurotransmitter metabolism—4-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, which degrades γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), and glutamate dehydrogenase, which mediates glutamate synthesis/breakdown—and on two metagenes enriched in IBS1 that are involved in short chain fatty acid metabolism—acetate co-A transferase subunit B, which mediates the final step of butyrate synthesis, and propionate catabolism operon regulatory protein, which regulates an operon of propionate catabolism genes (Fig. 5a). The individual taxa that made the greatest contribution to the association of these metagenes with IBS1 were identified using FishTaco. This highlighted a prominent role for one particular taxon, an unclassified Peptostreptococcaceae, which had a trend toward significant correlation (p = .058) with the right inferior segment of the circular sulcus though it fell short of significance as compared to the metagene encoding 4-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (p = .008) (Fig. 5b).

Bacterial genes involved in the metabolism of neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids correlate with the surface area of the right inferior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula (R Inf Cir Ins). a Relative abundances in IBS1, HC-IBS, and HC are shown for four of the metagenes, e.g., genes predicted by PICRUSt associated with the surface area of the right inferior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula (R Inf Cir Ins). Statistical significance was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test; *p < .05, **p < .01. The contribution of individual taxa to the significance of metagene differential abundance between IBS1 and HC was evaluated using FishTaco. The positive and negative effects of taxa on significance are shown separately for taxa more abundant in IBS1 and those more abundant in HC. Taxa could influence significance either by carrying the predicted gene (marked by an asterisks) or by being correlated with other taxa carrying the gene. “Other” refers to the total effect of all other taxa (out of 363) included in the analysis. b Surface area of the R Inf Cir Ins is plotted against the relative abundances of K00043 and the Peptostreptococcaceae OTU accounting for the majority of the predicted differential abundance of this metagene. Linear regression trendlines are shown along with the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and p value

Discussion

This exploratory study aimed to identify possible correlations between gut microbial community structure and brain architecture. The main findings of the study were (1) The identification of IBS subgroups based on distinct microbial clusters with only one of these subgroups (IBS1) showing gut microbial and some behavioral and clinical differences; (2) The identification of differences in the abundance of certain microbial taxa between IBS1 and HCs; and (3) The correlation of microbial taxa and imputed metagenes with structural brain alterations primarily in sensory integration and salience network regions in IBS1. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating a correlation between the architectures of the brain and the gut microbiota in a distinct subgroup of IBS patients. These findings suggest a possible influence of the gut microbiota and their metabolites on specific brain structures which may play a role in the pathophysiology of altered sensory processing in IBS.

Identification of IBS subgroups, based on microbiome diversity and relative abundance of the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes

Both hierarchical clustering using average linkage and PCoA analysis on unweighted Unifrac distances indicated that microbial signatures can be used to identify two subgroups among the IBS subjects, one that has a microbial composition similar to HCs, and one that shows a distinct gut microbial signature. This differentiation was also supported by our Random Forest classifier. Identification of the subgroups was not associated with sequencing depth. As a group, all IBS subjects showed significantly greater alpha diversity and richness than HCs, a difference that was largely explained by the greater diversity within the IBS1 subgroup. Higher alpha diversity has previously been reported in an IBS subgroup [10], in patients with celiac disease [51], and with autism spectrum disorder [52], all syndromes which are often accompanied by IBS-like symptoms. Even though an increased microbial diversity has been associated with diets high in fruits, vegetables, and fiber [53], a detailed dietary analysis between the groups did not reveal significant differences in dietary intake.

Subjects within the IBS1, but not the HC-like group, differed from the HC group in the relative abundances of the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (F-B ratio). While the abundance of Firmicutes was significantly greater in IBS1, that of Bacteroidetes was lower. In contrast, the HC-like IBS group did not differ from the HC with respect to these relative abundances. The finding of gut microbiota-based IBS subgroups and some of their gut microbial composition is similar to findings recently reported by Jeffery et al. [10], even though they identified two IBS clusters that differed from HCs in addition to a subgroup similar to HC. The finding of IBS subgroups based on gut microbial composition that had identical clinical symptoms suggests that the difference in microbial architecture is either not necessary for symptom generation in IBS, or that identical clinical presentations can be caused by different underlying mechanisms, one involving gut microbial alterations. Similar to the current finding in the IBS1 subgroup, both clusters in Jeffrey’s study showed a greater abundance of Firmicutes and a lower abundance of Bacteroidetes. Altered F-B ratios have been reported in other chronic diseases [54], with increased F-B ratios reported in both preclinical and clinical studies of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and high fat intake [55,56,57].

The reason for the increased F-B ratio found in this and in previous studies in IBS subjects [8, 9] remains unknown. F-B ratios in healthy individuals are highly variable, despite similarities in microbial function [58]. However, age [59] and diet [55, 57, 60] are important modulatory factors. For example, animal models of obesity, obese individuals, those with metabolic syndrome, and those on a Western diet with high animal fat content were found to have increased F-B ratios [55,56,57]. Fatty acids in high fat diets, such as in the typical North American diet, have been shown to increase the F-B ratio, and this increase has been associated with an increase in gut epithelial permeability and low grade inflammation [61]. It is intriguing to speculate that the increased F-B ratio in a subgroup of IBS patients is related to alterations in epithelial permeability and low grade inflammation which have been implicated as possible disease mechanisms in IBS [62]. Even though we observed trends for higher BMI and higher plant-derived fat intake in the IBS1 group, these differences did not reach statistical significance. Specific dietary habits, such as increased consumption of fat, have not been reported for IBS [63, 64]. No other dietary differences between the groups were identified.

In addition to the differences in relative abundances at the phylum level, several differences at lower taxonomic levels were also observed. The IBS1 group showed a greater relative abundance of several Firmicutes-related taxa, including members of Bacilli and Clostridia at the class level, of Bacilli-associated Lactobacillales at the order level, and of Holdemania at the genus level. The IBS-associated enrichment in Clostridia is particularly interesting in light of the finding that select spore-forming bacteria, dominated by Clostridia Cluster IV and XIVa, sufficiently induce serotonin biosynthesis by colonic enterochromaffin cells [65]. This aligns well with the reported links between intestinal serotonin dysregulation and IBS [66]. Holdemania are commonly found in the healthy gut, but there are few generalizable results for this genus. IBS1 differed in these relative abundances from both HC-like IBS and HCs, with the exception of differences in the abundance of Lactobacillales, which were only seen in comparison to HCs. This finding is surprising in view of the common recommendation of probiotics to treat IBS symptoms, the majority of which contain Lactobacilli. As acute laboratory stressors have been shown to decrease Lactobacilli in the stool in both clinical and preclinical studies, one would expect a reduction of Lactobacilli in a stress-sensitive disorder like IBS.

In addition to the increased abundance in some microbes, the IBS1 group had lower relative abundances of Bacteriodia at the class level, of Bacteroidales at the order level, and of Parabacteriodes at the genus level. All these differences were significant when compared to the HC group, but not the HC-like IBS group. The random forest analysis showed that OTUs contributing to the differentiation of IBS1 from HC gut communities included members of the genera Blautia, Streptococcus, Faecalibacterium, and Bacteroides.

The reasons that the group differences in relative abundance at lower taxonomic levels differed from those reported by others [9, 10, 67] are unknown, but may include differences in patient populations, diet, DNA extraction techniques, and the primers used for amplicon generation, as well as differences with respect to bioinformatic pipelines, data transformations, and the statistical approaches applied to the data.

Correlation of gut microbial composition with behavioral and clinical parameters

Similar to Jeffrey’s findings, we found few correlations between the gut microbial-based subgroups and clinical parameters such as IBS symptom severity, predominant bowel habit, or medication use, except for a moderate correlation with symptom duration. As subjective ratings of predominant bowel habits generally show poor correlations with colonic transit times, and the colonic transit times are normal in the majority of IBS patients regardless of reported predominant bowel habit, the observed lack of correlation of such ratings with microbial composition is not surprising. As commonly observed in clinical studies, IBS patients as a group had a significantly higher level of anxiety symptoms while IBS1 and HC-like IBS did not differ from each other. However, no correlations between anxiety (or depression) symptom scores and microbial parameters were observed.

Interestingly, IBS1 had significantly greater scores on the emotional scale of the ETI than both the HC-like IBS and HCs. While the relative abundance of the Firmicutes-associated class Bacilli was positively correlated with ETI total score, as well as with scores in the sexual and emotional subscales of the ETI, no correlations with EAL were found for the Firmicutes-associated class Clostridia, or the Bacteriodetes-associated class Bacteroidia. Even though the observed correlation between a history of ELAs and the microbiome needs to be confirmed in future studies, one may speculate that brain driven disturbances of the gut microbial environment in early life [12] may have a long lasting effect on gut microbial composition persisting throughout life, which in turn may lead to further changes in brain structure/function.

Correlation with brain structures

Moderate-sized correlations with brain structure were observed for certain Firmicutes- and Bacteroides-associated taxa. For example, the Firmicutes-associated Clostridia (higher in IBS1) and the Bacteroidetes-associated Bacteroidia (lower in IBS1) showed correlations with the volume of several subcortical brain regions involved in sensory integration and modulation and the motor cortex. For the majority of these regions, increased volumes were observed with decreases in Bacteroidia taxa and increases in the Clostridia taxa characterizing IBS1. On the other, decreased volumes of the anterior insula and ventral prefrontal regions were associated with the taxa profile of IBS1. Whether Clostridia-mediated modulation of peripheral serotonin levels [65] may be involved is unclear, increasing evidence reveals microbiome-mediated changes in neurochemical signaling and neurophysiology. The abundance of the Firmicutes-associated Bacilli (increased in IBS1) was related to only a few regional brain volumes including positive correlations with the right nucleus accumbens and subregions of the frontal gyrus, and negative correlations with other prefrontal cortices and the posterior cingulate cortex.

Previous structural and white matter studies have shown IBS-related alterations in some of the same regions, with IBS patients showing larger gray matter volumes [68] and altered white matter tracts in the thalamus and basal ganglia [69], and reduced gray matter volumes in insula and prefrontal cortices [68]. Several possible explanations for these structural brain changes have been proposed, including genetic and epigenetic factors, the effect of gut microbial metabolites, as well as the effect of longstanding increased sensory signaling from the periphery [6].

The biological mechanisms underlying the observed correlations remain to be determined. For the sensory brain regions, it is conceivable that neuroactive or proinflammatory metabolites generated by altered gut microbiota reach the brain, inducing neuroplastic changes. As most patients with IBS symptoms have a longstanding history of symptoms, often dating back to childhood, it is likely that such altered gut microbiota to brain signaling could have shaped the brain from early on in life. This view is also consistent with the observed correlation of microbial composition with EALs.

In support of this possibility, we found that the surface area of the posterior insula was associated with the predicted abundance of 20 bacterial genes increased in the IBS1 group. The posterior insula is considered the primary visceral cortex and was chosen a priori without corrections for type I error. The identified genes included two that influence synthesis/degradation of GHB and glutamate. GHB is a neurotransmitter found naturally at high levels in the intestine that inhibits intestinal peristalsis via GABAB receptors and has sedative effects in the CNS [70, 71]. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter in the enteric nervous system and in the brain where it also plays an important role in synaptic plasticity [72]. The posterior insula was also associated with abundance of a subunit of butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase, an enzyme used by intestinal bacteria such as Faecalibacterium in the final step of butyrate synthesis [73, 74]. Butyrate has histone deacetylase activity and signals through GRP43 and GRP109a (expressed by enterochromaffin cells, vagal afferents, and microglia), all potential mechanisms by which it could influence brain function or structure [75]. Interestingly, a positive regulator of proprionate catabolism operon was also associated with this region of the posterior insular, suggesting a shift in the short-chain fatty acid profile [76]. Association of these metagenes with IBS1 group was largely attributable to a single unclassified member of the Peptostreptococcaceae. It is unclear why this taxon bloomed in a subset of IBS patients, though diet or fiber supplementation are possibilities [77]. Mechanistic studies in rodent models are warranted to investigate these hypotheses.

There are several limitations to this study. The sample was relatively small and composed of both male and female subjects and did not include measures of intestinal transit times. Self-ratings of bowel habits are known to have a poor correlation with intestinal transit time. All correlations with brain structure were cross sectional, and no conclusion about causality can be made from our results. The observed gut microbial changes could be secondary to altered autonomic nervous system output to the gut, changing the microbial environment [78]. Alternatively, the brain changes could be the consequence of altered signaling to the brain through microbial metabolites, or both mechanisms may be involved [6]. Sequencing depth of the microbiome may be a limitation as rare members of the microbiota may be undetected, and differences in sequencing depth may affect relative distributions of microbial taxa. Finally, predicted metagenomics analysis to impute potential metabolites involved in the observed structural brain differences is limited, and results need to be confirmed by metabolomics analyses.

Conclusions

In summary, this is to our knowledge the first report demonstrating an association of gut microbial composition and function with regional brain structural changes in IBS. Regardless of the causation underlying the observed associations, several intriguing conclusions can be made from this study. Both the correlations of abundance of certain microbial taxa with early adverse life events and with distinct brain structural changes previously reported in IBS suggest a possible role of gut microbes and their metabolites in the development and shaping of the gut-microbiota-brain axis early in life. Confirming results from a previous study [10], IBS subgroups can be identified based on gut microbial composition, which do not correlate with clinical findings such as bowel habits, or with psychological symptom scores. These findings suggest the possibility of a new classification of IBS patients based on gut microbial signatures (and eventually on metabolomics profiles) rather than on clinical characteristics. Furthermore, consistent with clinical observations, the findings suggest the possibility that treatments aimed at altered gut microbial composition with antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, and certain diets may only work in subgroups of patients with an altered gut microbiome. Not only could such subgroups explain the lack of response to such treatments in a significant proportion of patients but also the worsening of IBS symptoms in subsets of patients with intake of food, fiber supplementation, and even probiotics. Identifying IBS subgroups based on gut microbiota, their related metabolomic profiles and corresponding brain signatures is likely to play an important role in optimizing therapies in IBS.

References

Simren M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, Spiegel BM, Spiller RC, Vanner S, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62(1):159–76.

Mayer EA, Savidge T, Shulman RJ. Brain-gut microbiome interactions and functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(6):1500–12.

De Palma G, Collins SM, Bercik P. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(3):419–29.

Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterol. 2016. Feb 19. [Epub ahead of print]

Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1662–71.

Mayer EA, Labus JS, Tillisch K, Cole SW, Baldi P. Towards a systems view of IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(10):592–605.

Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Malinen E, Aarnikunnas J, Tuimala J, Paulin L, et al. Microbial community analysis reveals high level phylogenetic alterations in the overall gastrointestinal microbiota of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:95.

Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, Kajander K, Kekkonen RA, Tims S, et al. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1792–801.

Saulnier DM, Riehle K, Mistretta TA, Diaz MA, Mandal D, Raza S, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiome signatures of pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1782–91.

Jeffery IB, O’Toole PW, Ohman L, Claesson MJ, Deane J, Quigley EM, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(7):997–1006.

Coutinho SV, Plotsky PM, Sablad M, Miller JC, Zhou H, Bayati AI, et al. Neonatal maternal separation alters stress-induced responses to viscerosomatic nociceptive stimuli in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282(2):G307–16.

De Palma G, Blennerhassett P, Lu J, Deng Y, Park AJ, Green W, et al. Microbiota and host determinants of behavioural phenotype in maternally separated mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7735.

O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(3):263–7.

Bohorquez DV, Liddle RA. The gut connectome: making sense of what you eat. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(3):888–90.

Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):578–9.

Mayer EA, Gupta A, Kilpatrick LA, Hong JY. Imaging brain mechanisms in chronic visceral pain. Pain. 2015;156 Suppl 1:S50–63.

Teicher MH, Samson JA. Annual research review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):241–66.

Labus J, Oezguen N, Hollister EB, Tillisch K, Savidge T, Versalovic J, et al. Regional brain morphology is associated with gut microbial metabolites in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):S-142.

Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1394–401. 401 e1-4.

Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1377–90.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. quiz 4-57.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66.

Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. The early trauma inventory self report (ETI-SR). Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4):A340-A.

Robinson ME, Riley 3rd JL, Myers CD, Sadler IJ, Kvaal SA, Geisser ME, et al. The Coping Strategies Questionnaire: a large sample, item level factor analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(1):43–9.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Subar AF, Midthune D, Kulldorff M, Brown CC, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Evaluation of alternative approaches to assign nutrient values to food groups in food frequency questionnaires. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(3):279–86.

Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–55.

Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis - II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. NeuroImage. 1999;9(2):195–207.

Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis - I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage. 1999;9(2):179–94.

Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage. 2006;31(3):968–80.

Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. NeuroImage. 2010;53(1):1–15.

Methe BA, Nelson KE, Pop M, Creasy HH, Giglio MG, Huttenhower C, et al. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012;486(7402):215–21.

Aagaard K, Petrosino J, Keitel W, Watson M, Katancik J, Garcia N, et al. The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB J. 2013;27(3):1012–22.

Riehle K, Coarfa C, Jackson A, Ma J, Tandon A, Paithankar S, et al. The Genboree Microbiome Toolset and the analysis of 16S rRNA microbial sequences. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13 Suppl 13:S11.

Jumpstart Consortium Human Microbiome Project Data Generation Working G. Evaluation of 16S rDNA-based community profiling for human microbiome research. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39315.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–6.

Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–9.

Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21(3):494–504.

Wang XW, Zhang L, Jin LQ, Jin M, Shen ZQ, An S, et al. Development and application of an oligonucleotide microarray for the detection of food-borne bacterial pathogens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76(1):225–33.

Ramette A, Tiedje JM. Multiscale responses of microbial life to spatial distance and environmental heterogeneity in a patchy ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(8):2761–6.

Navas-Molina JA, Peralta-Sanchez JM, Gonzalez A, McMurdie PJ, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Xu Z, et al. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol. 2013;531:371–444.

Faith DP. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol Conserv. 1992;61(1):1–10.

Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(12):8228–35.

Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26(1):32–46.

Kuhn M, Wing J, Weston S, Williams A, Keefer C, Engelhardt A, et al. caret: classification and regression training. R package. 6.0-73 ed. 2016.

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:77.

Langille MG, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):814–21.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550.

Manor O, Borenstein E. Systematic characterization and analysis of the taxonomic drivers of functional shifts in the human microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(2):254–67.

Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145(5):745–57.

Robinson CJ, Bohannan BJ, Young VB. From structure to function: the ecology of host-associated microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(3):453–76.

Cotillard A, Kennedy SP, Kong LC, Prifti E, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, et al. Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature. 2013;500(7464):585–8.

Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148(6):1258–70.

Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1022–3.

Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2126–32.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–31.

Backhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, Sanders ME, Sartor RB, Sherman PM, et al. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(5):611–22.

Mariat D, Firmesse O, Levenez F, Guimaraes V, Sokol H, Dore J, et al. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:123.

Albenberg LG, Wu GD. Diet and the intestinal microbiome: associations, functions, and implications for health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(6):1564–72.

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–72.

Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, Farmer AD, Fukudo S, Mayer EA, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16014.

Bohn L, Storsrud S, Simren M. Nutrient intake in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared with the general population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(1):23–30. e1.

Jarrett M, Heitkemper MM, Bond EF, Georges J. Comparison of diet composition in women with and without functional bowel disorder. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1994;16(6):253–8.

Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161(2):264–76.

Mawe GM, Hoffman JM. Serotonin signalling in the gut—functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(8):473–86.

Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salojarvi J, Salonen A, Immonen O, Garsed K, Kelly FM, et al. Faecal microbiota composition and host-microbe cross-talk following gastroenteritis and in postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2014;63(11):1737–45.

Labus JS, Dinov ID, Jiang Z, Ashe-McNalley C, Zamanyan A, Shi Y, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in female patients is associated with alterations in structural brain networks. Pain. 2014;155(1):137–49.

Ellingson BM, Mayer E, Harris RJ, Ashe-McNally C, Naliboff BD, Labus JS, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging detects microstructural reorganization in the brain associated with chronic irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2013;154(9):1528–41.

Carai MA, Agabio R, Lobina C, Reali R, Vacca G, Colombo G, et al. GABA(B)-receptor mediation of the inhibitory effect of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid on intestinal motility in mice. Life Sci. 2002;70(25):3059–67.

Tedeschi L, Carai MA, Frison G, Favretto D, Colombo G, Ferrara SD, et al. Endogenous gamma-hydroxybutyric acid is in the rat, mouse and human gastrointestinal tract. Life Sci. 2003;72(22):2481–8.

Seifi M, Swinny JD. Immunolocalization of AMPA receptor subunits within the enteric nervous system of the mouse colon and the effect of their activation on spontaneous colonic contractions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(5):705–20.

Louis P, Duncan SH, McCrae SI, Millar J, Jackson MS, Flint HJ. Restricted distribution of the butyrate kinase pathway among butyrate-producing bacteria from the human colon. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(7):2099–106.

Louis P, Flint HJ. Development of a semiquantitative degenerate real-time pcr-based assay for estimation of numbers of butyryl-coenzyme A (CoA) CoA transferase genes in complex bacterial samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):2009–12.

Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett. 2016;625:56–63.

Palacios S, Escalante-Semerena JC. prpR, ntrA, and ihf functions are required for expression of the prpBCDE operon, encoding enzymes that catabolize propionate in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(4):905–10.

Cox LM, Cho I, Young SA, Anderson WH, Waters BJ, Hung SC, et al. The nonfermentable dietary fiber hydroxypropyl methylcellulose modulates intestinal microbiota. FASEB J. 2013;27(2):692–702.

Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6(5):306–14.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the mathematical and technical support of Dr. Antonio Gonzalez, PhD in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable editorial services of Cathy Liu.

Funding

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P50 DK064539 (EAM).

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01 DK048351 (EAM).

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine R01 AT007137 (KT).

Availability of data and materials

Sequence data associated with this project have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive under BioProject accession PRJNA373876.

Authors’ contributions

JL and JJ contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis. EBH contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, and technical support. EH contributed to the interpretation of the data. KK contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. NO, KA, and RAL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and technical support. AG contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, technical support, and drafting of the manuscript. JA contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and data analysis. JV and TS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. KT contributed to the study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and study supervision and obtained funding. EAM contributed to the study concept and design, study supervision, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and obtained funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board, IRB#12-001802-CR-00004, IRB#12-000837-CR-00004.

Short summary

This article confirms previous reports that subgroups of irritable bowel syndrome subjects can be identified based on differences in gut microbial composition. It demonstrates for the first time an association of these subgroups with specific structural brain alterations.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

NHANES. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Cortical and subcortical brain regions. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 3:

Bioinformatics Workflow. (TXT 9.85 kb)

Additional file 4: Figure S1.

Two-dimensional plots of the principal coordinate analysis. The plot of principal component (PC) 3 versus PC 2 demonstrates presence of clusters or groupings based upon operational taxonomic unit (OTU)-level microbial features. IBS subjects are represented as blue squares. Healthy control subjects are represented by red circles. (PNG 36 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S3.

Relative abundances of observable taxonomic units (OTUs) correlated most strongly with the location along the 3rd axis of the principal coordinate analysis (r > .45). (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S2.

Faith’s phylogenetic alpha diversity curves depicting richness of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) as a function of sequencing depth. Rarefaction curves are a plot of the number of species as a function of the number of samples. (PNG 476 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S4.

OTUs contributing to the differentiation of IBS versus HC gut communities. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 8: Figure S3.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the operational taxonomic unit (OTU)-based Random Forest model which correctly distinguished the IBS1 subtype from HC and HC-IBS. AUROC: area under the ROC curve. (PNG 2134 kb)

Additional file 9: Table S5.

Relative abundance of operational taxonomic units and taxa showing significant group differences. (DOCX 20 kb)

Additional file 10: Table S6.

Mean difference in clinical metadata between IBS subgroups based on microbiota IBS subgroups. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 11: Table S7.

Metagene associations with brain morphometry and microbiota clusters. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Labus, J.S., Hollister, E.B., Jacobs, J. et al. Differences in gut microbial composition correlate with regional brain volumes in irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiome 5, 49 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0260-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0260-z