Abstract

The concept of social resilience thrives in studies and policies of fisheries and marine conservation. Associated with the ability of communities to adapt to change, it has spurred debates on social organisation for resilience. Considering its proliferation in maritime studies, the concept of social resilience requires a critical reflection on the ontological assumptions of ‘social’ and ‘community’ that undergirds the concept, in particular the idea that communities are place-based. Following a relational ontological approach, this article proposes to explore community as performative network of human and non-human relations acted out in practice. Drawing on insights from ethnographic research in a coastal region in Indonesia, I illustrate the performance of community networks beyond the local scale and how they sustain through the association of social and material elements. These trans-local communities have resisted conservationists’ attempts to create resilient (place-based) fishing communities in the region to impede illegal fishing. The case illustrates how a relational approach helps to illuminate what social resilience in a maritime context means in practice. The article aims to contribute to critical social resilience scholarship in maritime studies by drawing out how we may think and explore ‘social’ and ‘community’ otherwise and the implications this has for how we look for resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At first sight, Pantai Bakau appeared as a remote fishing village. The majority of homes consisted of simple stilt houses made of palm leaves and wood from the forest behind the village. Most houses faced seawards, and some were even built over water. The mangrove forest covering most of the coastline was spotted with small wooden fishing boats, ready for take off to sea at high tide. Situated at the curve of a shallow bay, the little village seemed to be literally the end of the road. The palm-flanked sandy pathway connecting the houses came to an end at a creaking village jetty. Only boats would take one further south.

I reached the village for the first time in 2009, after an exhausting eight-hour drive from Tanjung Redeb, the capital town of the Berau Regency in East Kalimantan. At the time, Pantai Bakau was one of the target villages for the community-building efforts of the Joint Program, a regency-based conservation platform in which WWF (World Wildlife Fund) and TNC (The Nature Conservancy) collaborated to bring about marine conservation and sustainable fishing in Berau’s coastal waters. The Joint Program intended to stimulate local community participation in marine conservation and to help (village-based) communities organise to protect their fishing grounds from illegal fishing (Wirjawan et al. 2005). Since 2005 the coastal zone of the Berau Regency had been designated as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) (Kusumawati and Visser 2014). In the Joint Program’s policies, marine conservation was combined with community development programs-such as microcredit schemes, alternative livelihoods, and village-based surveillance (Gunawan 2012; Soekirman et al. 2009). It was hoped that these combined efforts would lead to a seascape that was socially and ecologically resilient (IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas IUCN-WCPA 2008: 93; Wilson et al. 2010: 4).

Nevertheless, at the time of research, conservation measures in Berau did not meet the desired support among the local population, and destructive and illegal fishing was still widely practiced (Gunawan and Visser 2012; Pauwelussen 2015). My fieldwork in Pantai Bakau was motivated by the wish to understand how local forms of social organisation and marine resource management in coastal Berau related to the interventions by the Joint Program to enhance social (community) resilience for the ultimate goal of marine conservation.

Yet, as is shown further on, shortly after starting the fieldwork in Pantai Bakau I had to reconsider the idea of the village as a local community. Whenever I made an effort to explore historical and present relations of community in the village, I soon found myself transported to another place. ‘Village’ turned out to be only one of different ways in which community was acted out. Although prominent in the organisation of community-outreach, other (trans-local) forms of community appeared more persistent in fishing and trade practices, yet were at odds with the local ‘village’ community envisioned by the Joined Program. To investigate social resilience of (the) community, the research therefore shifted to exploring how and where community-and social resilience-was performed in the first place. This article is informed by this ethnographic exploration of what community comes to be in different practices, which led to a critical reflection on the ontological basis of social resilience.

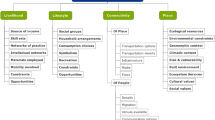

The concept of social resilience has thrived in studies and policies of fisheries and marine conservation. It has been applied mostly in institutional perspectives of social organisation, in which resilience has come to refer to the strength and social cohesion of coastal or fishing communities (Adger et al. 2002; Cinner et al. 2009; Healey 2009; Pitchon 2011). It has been argued that effective marine conservation and fisheries regulations requires resilient communities, with a strong ‘sense of community’ (Jentoft 2000), as this enhances local capacity to act collectively towards external threats to local marine resource bases (Pinkerton 2009). The resilience concept was adapted from the social-ecological resilience framework, prevalent in ecosystem analysis, that considers ecosystems and human societies as dynamically intertwined (Adger 2000; Berkes et al. 2003). Dealing with change and adaptation, resilience thinking has inspired debates on how maritime communities (can) buffer or adapt to social-ecological change related to (for example) coastal development, climate change or unsustainable fishing (Adger et al. 2005; López-Marrero and Tschakert 2011; Ratner and Allison 2012) and has cross-fertilized with studies of vulnerability and wellbeing in fisheries (Béné et al. 2014; Coulthard 2012).

Despite the recent proliferation of social resilience studies in a fisheries context, the concept of social resilience itself remains weakly theorized (Fabinyi et al. 2014). As a theoretical model, it lacks a thorough consideration of what ‘social’ and ‘community’ mean, and how their resilience comes about. Cote and Nightingale (2011) have argued that, influenced by a ‘modelling culture’, resilience scholarship has used rather unspecified notions of ‘social’ in institutional frameworks, without a proper grounding of the concepts in qualitative, empirical research. Ongoing empirical grounding is needed to keep such concepts in touch with the dynamic ways in which people organise, and how this comes about. Also, it facilitates the critical reflection on the biases undergirding (social) resilience models and policy frameworks (Fabinyi et al. 2014).

Bush and Marschke (2014) have pointed out that despite attempts to connect the social and the ecological in resilience thinking, a truly integrated and interdisciplinary understanding of social resilience has been hampered by the tendency of resilience scholarship to fit the social within the epistemological and ontological boundaries of systems thinking. Critical social scientists have addressed these conceptual limitations by formulating new notions of social resilience that take into account concerns of power, agency and social diversity (Béné et al. 2014; Fabinyi et al. 2014). Human intentionality has been taken in to acknowledge the ability of people (individuals and collectives) to affect their circumstances to enhance their resilience (Berkes and Ross 2013; Bohle et al. 2009), also in the fisheries context (Broch 2013; Coulthard 2012). Yet, although critical resilience scholarship is growing, still the idea of there being something (a realm or quality) distinctively social is often taken for granted. This shows in the frequent use of the word social as a pronoun-such as “social fabric” (Béné et al. 2014) without explanation of what it refers to, yet used to explain resilience. As the notion of community/social resilience wins terrain in debates in maritime research and policy, it is expedient that the ontological basis of ‘social’ and ‘community’ is critically reflected on.

Latour (2005) has made a distinction between a ‘sociology of the social’ in which the term ‘social’ is used to explain other processes and phenomena and a ‘sociology of associations’ that explores instead how the social is assembled. Rather than assuming a social fabric to exist ‘out there’ holding the community together, a sociology of associations traces how the ‘social fabric’ is itself woven in practice, possibly from unexpected threads. Latour’s ‘sociology of associations’ is based on a relational and performative ontological approach identified with (among others) Actor-Network Theory (ANT) (Callon 1986; Latour 2005; Law 2009), and the ‘ontological turn’ in anthropology (Blaser 2009; Viveiros de Castro, E. 2003). Although still marginal in mainstream maritime studies, a fair variety of accounts on fisheries, fish farming and marine conservation has emerged from such a relational ontological approach (e.g., Bear 2012; Blanco et al. 2015; Eden and Bear 2012; Law and Lien 2013; Pauwelussen and GE Verschoor Forthcoming). These accounts have in common that they make no prior distinction between a ‘social’ and ‘ecological’ realm, but instead follow and describe relations between a wide array of elements (such as fish, sounds, spirits, vaccines and slippery surfaces) to explore how maritime networks (or worlds, assemblages) of relations come about, persist, or are resisted. Dwiartama and Rosin (2014) have indicated the relevance of a relational (ANT) approach to the reconceptualisation of resilience: It allows for empirically exploring how networked forms of resilience come about and what kind of (human or non-human) actors participate in the process.

Continuing along this line of thought, this article employs a relational ontological approach to explore the enactment of community as a performative network. ‘Performative’ here refers to the premise that the network is continuously enacted in practice, and therefore a contingent accomplishment. I take inspiration from ANT to acknowledge that as a performative network, community relations also rely on the enrolment of material components to become or stay resilient. ‘Network’ is used here not as an alternative definition of community, but as an analytical metaphor to explore relational enactment. It is my primary objective to discuss, and illustrate with ethnographic material, how such relational approach to the social is helpful in illuminating what social resilience in a maritime context means in practice. The article thereby aims to contribute to the critical literature on resilience thinking, in maritime issues in particular, by drawing out how we may think and explore resilience otherwise.

In the next section I scrutinise the assumptions of the bounded community (‘community-as-container’) in resilience scholarship, and subsequently discuss how a relational concept of community (‘community-as-network’) can complement the study of social resilience in a maritime context. In section three I draw on insights from fieldwork in and beyond the coastal village Pantai Bakau to illustrate what different views on community, place and resilience a performative network-approach generates. The ethnography shows the enactment of trans-local, sea-based forms of community as resilient networks-involving kinship, trade and patron-client relations. Next, I link these insights to recent efforts of conservation organisations to enhance (village-based) community resilience along Berau’s coast to impede illegal fishing. In the conclusion I reflect on what a relational ontological approach to the social contributes to the study and conceptualisation of social resilience.

The ethnographic data on which this article is based was collected during 3 months of fieldwork in 2009, followed by 18 months of fieldwork in 2011–2013, and two shorter visits in between. The primary methods were informal interviewing, participant observation and the writing of field notesFootnote 1.

Community: container or network?

Community as container

Fabinyi et al. (2014) have identified several biases that remain influential in how resilience scholarship has conceptualised the social. Among these are the tendency to homogenise social diversity and the common association of resilience with positive outcomes. Bush and Marschke (2014) have linked these biases to the systems ontology in resilience thinking, in which power and social complexity don’t get due attention. Rather, the social is framed as organised social units (communities) that fit an institutional design, in which consensus and homogeneity are emphasised over contestation and difference (Cote and Nightingale 2011; Fabinyi et al. 2014).

How we frame our units of analysis affects how and where we look for resilience. The preoccupation in the resilience paradigm with how communities should be to fit institutional designs for social resilience (Pinkerton 2009) should not overshadow empirical investigations of how resilient communities come about, where, and who benefits (or not). For example, Coulthard (2012) has shown how enhancing resilience of a fishing community may actually be at the expense of individual wellbeing (see also Béné et al. 2014). Bohle et al. (2009) have shown that through a systems-oriented approach resilience can be seen differently than from a people-centered perspective. Interventions to enhance resilience of a social-ecological system may significantly reduce the resilience of those whose livelihoods are affected. Conversely, what certain groups may regard as ‘good’ resilience (e.g., the lucrative trade in sea turtle eggs (Kusumawati 2014)) can be considered ‘bad’ resilience for the social-ecological system.

The current critique on social resilience and attempts to reconceptualise it to account for dilemmas of power and social differentiation resonates with earlier discussions in anthropology and critical development literature (cf Fabinyi et al. 2014). In this body of literature the idea of communities as egalitarian, homogeneous and spatially bounded groups has been extensively scrutinised (Brosius et al. 2005; Li 1996). Agrawal and Gibson (1999) have stressed the importance of power differences in communities for conservation outcomes, and pointed out how shared norms may actually support overexploitation of resources. They have proposed a shift in focus from communities to institutions. However, when institutions are viewed as structures that link local communities (640), the fallacy of assuming (local) social units re-emerges.

Indeed, one may observe that the spatial bias (and land-bias) in thinking community is persistent. Perhaps so much so, that it has become ubiquitous, making even critical social scientists sometimes unreflective of why a sense of belonging together, or support, should be place-based. Despite the mobility and trans-locality inherent in most sea-based livelihoods, it is often implicitly assumed that maritime communities are confined to terrestrial places, that they are of a local scale, and/or that they coincide with village boundaries (Cinner et al. 2009; IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas IUCN-WCPA 2008; Jentoft 2000; Johnson 2001; Pinkerton 2009).

St. Martin and Hall-Arber (2008) have written about the prevalence of the 'container vision' in maritime studies: the notion of the coastal or fishing community as a social unit tied to the shore that contains cohesion-like glue-within. The ‘container’ notion comes with certain limitations. It ontologically derives the existence of social cohesion or sense of community from a land-b(i)ased demarcation; whether is it is a place of residence, ethnic roots or administrative divisions. A place-based or administrative notion of community is not ‘wrong’. Certainly, the village can be an important way in which a maritime community is enacted (e.g., Broch 2013). Yet it should not keep us from exploring other ways in/along which communities (or, indeed, institutions) are enacted.

This is particularly relevant for maritime societies in which sea-based and trans-local movement characterises how people associate. In Southeast Asia in particular, with its history of maritime trade and sea-nomadic people (Sather 2002; Tagliacozzo 2009; Warren 2007), sea-based and mobile communities of practice and kinship co-exist and cross-cut with place-based notions of belonging together (Chou 2003; Lowe 2003; Stacey 2007). Earlier research in East Kalimantan has shown that coastal people in this region often maintain strong kinship, trade and patron-client relations extending across the sea (Kusumawati et al. 2013), also beyond national boundaries (Visser and Adhuri 2010). It is therefore important to explore such trans-local and sea-based relations of belonging, support and material exchanges, and not confine the study of resilience to place-based communities.

Community as performative network

Exploring community as a (performative) network allows for an open-ended and empirical approach. A performative notion of network, based on a relational ontology (Latour 2005; Law 2009) differs from the way network is commonly used in institutional and systems approaches, in which network refers to the interconnection of (predetermined) communities, institutions and scales (Janssen et al. 2006; Marín and Berkes 2010). In a relational ontology, the social has no reality outside practice (Law 2009), and in practice any thing potentially is, belongs to, contains or partially connects to other networks. Any form of community as a sense of belonging together and mutual support exists-or rather comes into existence-and endures by way of enactment. This is not to say that community cannot be real. In practice, communities can be made real, but they offer no a-priori framework of explanation. This also means that the spatial scale of community is an effect of association, not a delineation of it. A community-as-network associates various elements or ‘actors’ that relate to, but are not confined to, places. Resisting the assumption of community boundaries beforehand clears the way for exploring how, where and when community-as-network is performed. Importantly, in such an approach community-as-container is a performance too, and probably a very resilient one considering its persistence in conservation and development practicesFootnote 2.

A relational ontology includes non-human actors as participants in the enactment of reality. According to Latour, “no science of the social can even begin if the question of who and what participates in the action is not first of all thoroughly explored, even though it might mean letting elements in which, for lack of a better term, we would call nonhumans” (Latour 2005: 72). For example, Callon (1986), Law and Lien (2013) and Moore (2012) have shown how the choreographies of human-animal interactions are formative of how fisheries and aquaculture are performed. According to Dwiartama and Rosin (2014), extending agency to ‘nonhumans’ allows for understanding (social) resilience as the result of the contingent and unpatterned interactions among humans and the material components that make human relationality possible, and durable. Taking in this insight, a study of community resilience becomes an exploration of how (human and non-human) actors associate into community-networks that endure. Yet, as communities are continuously enacted in practices of association, such resilience is a conditional and temporary accomplishment.

Considering communities as networks enacted in practices means that their performance can be described in ethnographic research, by engaging in different life worlds, joining practices and following relations, by which the fieldworker inevitably becomes partly immersed in the associations under study.

Enacting community in practice

Moving associations

Soon after arrival in Pantai Bakau, it occurred to me that the village population was travelling around a lot beyond the village, as it was common that people (men, women, children) stayed periods of time in other places, for work, study, support, gossip, celebration, fishing, or… just for the sake of it. Such visits ranged from a ten-minute walk to the next village to journeys to islands or settlements hundreds of kilometres away. Fishers and traders could be gone for days or weeks, staying in their boats or sleeping in coastal or island homes of friends and family. Soon I took part in this merry-go-round myself, joining fishing trips out at sea, following traders moving valuables to and from the village and coming along to visit people’s ‘close’ family in faraway places. Along the way, people often pointed out who and what was close to them (relatives, fishing spots, or the palm trees they owned), and who or what was from ‘elsewhere’ (not related, other). Meanwhile, these movements involved a ceaseless interchange of food, fish, vessels, wishes and stories that were brought along but also appeared to guide where and when to go. The more I delved into the village, the more the ‘local’ place turned inside out; into a hub of lines extending far beyond the village. It appeared that Pantai Bakau was woven together by interlacing lines of social and material exchanges that were not reducible to the geographical-administrative boundaries of the village.

From a land-based view, Pantai Bakau may seem like a typical out-of-the-way place; far away from the administrative centre and hard to reach due to poor infrastructure. Yet, from a sea-based perspective it appears as an entry point for migration (from the sea toward the land) and as a centre of primarily sea-oriented trade. From Pantai Bakau, fish, wood and coconuts were exported by boat to harbours along the west coast of Sulawesi, Sabah and East Kalimantan. ‘Market’ boats, with their home base in overseas towns passed by the village on a regular basis, selling rice, vegetables and fruits from Sulawesi’s highlands, as well as cosmetics, clothes and kitchen utensils. As a tiny sea gate Pantai Bakau’s jetty was the place where new products, stories, opportunities and future husbands arrived in the village.

According to the stories of residents, Pantai Bakau village was founded in the first quarter of the 20th century, by migrants from different ethnic backgrounds and oversees places who came to the Berau coast in search of fishing grounds, jobs in logging and trade or just a peaceful place to live. The majority of these migrants were seafaring Buginese and Mandar people from Sulawesi and semi-nomadic Bajau from Northern Borneo (Sabah, Malaysia) and the Southern Philippines. Pantai Bakau residents thus commonly traced their life- and family-histories to overseas places.

Illustrative of this is the story of YurniaFootnote 3 (Fig. 1), who often hosted me during fieldwork. Yurniah’s father had left his BajauFootnote 4 village in Semporna (in Sabah, present-day Malaysia-then a British colony) in search of work when he was still a young man. He joined a boat southwards across (what is now) the Malaysian-Indonesian border, thereby following the tracks of his siblings. He ended up staying with relatives on islands in the Berau coastal area, which was under Dutch rule at the time. From there, he traded hardwood from the Berau coast to Tawau (Sabah) by boat. After marriage he continued further south to Sarang Island, in Berau. By the 1940’s, a thriving fish trade had emerged there, attracting fishers and maritime traders from far and wide. In the early post-colonial years, pirate attacks caused part of Sarang’s population (including Yurniah’s parents) to flee to the relative safety of Berau’s mangrove-covered coast. Some people stayed there in a new Bajau settlement (Teluk Indah). Yurniah’s parents however moved to a neighbouring village populated by Mandar and Buginese diaspora: Pantai Bakau. Yurniah’s parents acquired a stretch of land in Pantai Bakau, planted palm trees on it, and raised their children until some took off to work or settle elsewhere (just as their parents had done). Yurniah’s father became a well-respected man in the village, who even was in the position of village head for several years. Before he died, he divided the land and trees among his children, but only some of them were still living in the village.

This short version of Yurniah’s family history illustrates how a ‘local’ woman, living in a seemingly remote fishing community, relates her ancestry to faraway places in a seascape. Her story suggests that it would be unsound to assume a-priori that her sense of belonging to people and places was contained by a local scale, or firmly attached to the coastal village. Although Yurniah had lived most of her life on her father’s land in Pantai Bakau, she also strongly identified with affective relations overseas. Another example is Yurniah’s husband Anton, who was born near Manado (Sulawesi) and raised in Surabaya (Java). From the age of 16 until marriage, Anton had lived a sailor’s life for more than 15 years, alternating erratic associations and romances in different ports with much longer phases at sea, crossing borders to transfer all kinds of cargo to faraway places, like Jakarta, Singapore, Bangkok (Fig. 1). And he was no exception in the family; Anton's siblings and cousins had become dispersed over different Indonesian and Malaysian islands and coastal towns.

The stories of Yurniah and Anton are typical of the trans-local and mobile character of maritime societies in Southeast Asia (Tagliacozzo 2009; Warren 2007). Ethnic groups such as the Bajau (Sather 1997), the Buginese (Pelras 2000), Makassarese (Adhuri 2013) and Mandar (Zerner 2003) are renowned for sustaining communication, trade and exchange relationships over vast distances across the sea, often following real or ‘fictive’ kinship ties (Acciaioli 2000). Practices of maritime trade, seafaring and open-sea fishing are long-established traditions cultivated among the Buginese, Makassarese and Mandar in Indonesian waters. The Bajau (Sama-Bajau) are also known for their sea-nomadic lifestyles, yet nowadays their majority combines living in coastal and island settlements with seasonal migration for fishing, trade and family visits (Gaynor 2005; Lowe 2003; Stacey 2007).

An obvious result of such migratory life trajectories is that families spread out across seas, regions and states. In colonial and pre-colonial times, the coastal areas surrounding the island of Borneo were an operating field for maritime contact, with the sea as a “living conduit” connecting different ethnicities into a swirling maelstrom of trade and travel (Tagliacozzo 2009: 100–1). “Separated by wide expanses of sea, they nevertheless felt a sense of community with other maritime societies scattered throughout the region, usually more so than with their own neighboring hinterlands” (100). As one of the primary satellite homes for maritime communities in and around the island of Borneo, Berau has been involved in a continuous flux of arrivals from overseas, while others have moved on elsewhere away from Berau instead.

Such historical migration patterns are significant for how one thinks of belonging and place: At the time of research no one in Pantai Bakau identified with indigenous ties to Berau. Instead, tracing family ties and life trajectories of Pantai Bakau residents resembled a following of lines that strung out oversees. These lines of identification were rather fluid and mobile. One person could refer to different places as home, origin or community, referring to the village as ‘home’, while also expressing strong connections with other overseas places. Yurniah, for example, was from Pantai Bakau (where she lived), from Teluk Indah (where she was born), from Sarang Island (where she claimed to own palm trees), and from Semporna (where her father was born), or-sometimes she would say-just ‘from the sea’ or a ‘sea person’. Yurniah explained her ‘ownership’ of palm trees as having a family privilege and duty to take care of the trees on a regular basis, while the trees also took care of her family (by giving coconuts and leaves). Among the Bajau in Berau, a strong attachment was also expressed to ancestral graves, which were in most cases dispersed over different islands and coastal places. They considered such graves as constituted of vibrant spiritual-material components connecting the Bajau to their ancestral spirits. In addition, some Bajau fishers and seafarers in Berau regarded their boat as ‘mobile home’, as they spend days, weeks or months on board at sea, often taking along wife and kids.

According to Grillo and Mazzucato (2008), ambiguity in feelings of belonging is a common way migrants are doubly engaged with their place of residence while simultaneously maintaining significant social and economic ties to places of origin. However, the idea of belonging and place of origin as static and land-tied hardly applies to the fluid mobile and sea-based associations of Berau’s maritime population. We, therefore, need to depart here from the preoccupation with land-based communities and geographies, to include (other) maritime community relations and their seascapes (cf Malkki 1992).

Enactment

Throughout maritime South-East Asia, relations of affection, solidarity and interest are commonly classified and qualified by means of kinship terms, and references to the more general notion of ‘family’ (Acciaioli 2000; Pelras 2000; Sather 1997). In Berau, saying that a person is family (keluarga) was a common way to say he/she/it is ‘one of us’, or: ‘we belong together’ (which may include ancestral spirits, boats and palm trees).

Despite this prevalent ordering of social belonging through kinship, still such kinship and family ties require enactment. Through repeated visits and reciprocal exchanges, the family-as-community was performed in practice. Without such association practice, kin became ‘far’ instead of ‘close’, became ‘other people’ instead of ‘us’. For example, to Yurniah, ‘near’ (‘dekat’) relatives were those she sustained relations of interaction and exchange with while kin in a neighbouring village could be referred to as ‘far’ (‘jauh’) if they were not part of such reciprocal exchanges. ‘Near’ kin was visited, brought souvenirs (oleh-oleh) or sent a share of fish or rice. A return of visits and generosity was expected. Important were also the various ceremonial get-togethers, for example for a wedding, a circumcision or the commemoration of a deceased relative. For some of these get-togethers, Yurniah travelled for days over land or sea, staying with ‘near’ people along the way. In this enactment of family, social cohesion or a ‘sense of community’ emerges that is mobile and trans-local, and in which proximity is performed as a relational matter.

A shared ancestry, ethnic background or trade interest may be significant for how community associations take form. However, staying true to a ‘sociology of associations’ means refraining from seeing such qualities as determining how and where people, vessels, valuables and ideas move and associate. As I have shown elsewhere (Pauwelussen 2015) for informal fish trade networks in Berau, past travels and exchanges have formed ‘pathways’ along which subsequent exchanges and moves have been patterned yet not prescribed. The continuity of such patterns is only partly explained by the ‘social’ gossip sessions and phone calls, debt relations and exchanges among people. Boats, ice blocks, microbes, mobile phone signals, inscriptions and sea currents all participated in making these trade relations possible, in turn also mobilising humans to move and associate. It is this enacted interrelation of social and material elements that allows such webs and routes of trade relations to stabilise, however contingently, and affect future associations (cf also Law 1986).

This also applies to the historical migration routes of people to and from Berau. Fish have drawn people along their migration routes. The seasonal visits of different fish species in Berau’s coastal waters have attracted fishers, boats and gear specialised in hunting them down. Also, the thriving trade in hardwood logs from Kalimantan’s interior has mobilised Bajau entrepreneurs such as Yurniah’s father across the Indonesian-Malaysian border. Palm trees have affected people’s moves differently: Trees growing on islands have offered coconut refreshments to passing fishers, while those with permanent caretakers (such as in Pantai Bakau) have influenced people’s decision to stay put.

So far, I have illustrated some ways in which maritime community-networks in Berau were enacted in the relations, movements and exchanges between various human and non-human actors, along lines extending in different directions, yet patterned by the tracks of earlier journeys. What, then, can we make of resilience? What happened in times of crisis?

Contraction

At one time during fieldwork, Yurniah’s (resident) younger brother died unexpectedly. For three days in a row, a stream of people arrived at the house of Yurniah and Anton. Fish, mangoes, rice crackers, chickens and stories from other places accompanied the visitors in their cars, boats and bags. The first arrivals came from villages in the district. As high tide set in, boats arrived at the beach in front of the house, bringing people from Sarang Island and other offshore places. Four-wheel drives defied Berau’s muddy roads to bring relatives and friends from coastal towns up north to Pantai Bakau, followed by those who had to take an airplane to Berau first. The number of attending relatives (it must have been far over a hundred people) was impressive, all dwelling in and around the house, cooking, talking, eating, chasing chickens and playing dominoes. Even more overwhelming was the number of plates, pastries and stories. Piles of food were assembled from different places to feed everyone. While women cooked, young men went hunting for deer in the woods, and befriended and related fishermen brought shares of the day’s catch. Grief was ritualised by the joint performance of ceremonies - headed by Yurniah’s oldest brother-and the eating of sanctified food. At night, people all slept close to each other, side-by-side on rugs on the floor, while Yurniah’s sisters sang Koran verses in the kitchen. Men took turns for the nightly vigil, which turned out to be a night of storytelling, political discussions, and making new business arrangements.

Besides the act of collective mourning and support, critical events like a funeral also provide an opportunity to exchange information, valuables and food, to strengthen relationships and to start new plans for the future. For example, Anton discussed with relatives from Berau’s capital city how they could collaborate in order to profit from a planned road project. Also, while cooking, women shared their knowledge about recent marriage arrangements, deaths and births in the family as well as information about prices for fish, cloths and rice in different places. Importantly, the concentration of support involved being together, performing rituals and sharing ideas and emotions, but it also very much entailed the gathering of vessels, animals, sleeping rugs, stories, songs, cash money, and cutlery. The assembling, dispersal and consumption of animal protein was indispensable to this funeral event, as was the mobilisation of vehicles and vessels to take people and things safely to and from the village over land and sea. The very mobilisation of all these elements to gather in and around one household was in itself an achievement, especially considering the fact that there was no phone signal in the village (not to mention internet). This mobilisation of the ‘family’ involved youngsters driving their motorcycle to a nearby village in search of phone signal to call other relatives, who would then call others (etc.), and ‘mouth-to-ear’ transfer of the message by people travelling by all sorts of transport.

Describing how community is acted out as a ‘performative network’ that enrols and mobilises both social and material elements allows one to explore what (social) resilience possibly means in situated practices. To Yurniah and her family, the funeral described above was a financially costly event, however the gathering also provided for a strengthening of affiliations and a thriving exchange of both material and non-material valuables. In the funeral event, a form of community resilience took shape in the informal and pulsating network that the people called ‘family’; a contracting and expanding relational space that for a moment concentrated on Yurniah and Anton’s household.

Patron-client relations

Another way such networked coherence takes form in maritime Southeast-Asia is the patron-client relationship, in which notions of kinship or affinity are translated into business interests and vice versa (Acciaioli 2000; Meereboer 1998; Pelras 2000). This business/kinship convergence shows in how coastal fisheries in East Kalimantan are commonly organised along patron-client arrangements (Gunawan 2012; Kusumawati et al. 2013). The terms often used in Berau are ‘bos’ for patron and ‘anak buah’ (a fluid term used for (a merging of) ‘vessel crew’, ‘subordinate’, or ‘part of the family’) for the clientsFootnote 5. While patrons preferred to recruit their anak buah through relations of blood or marriage, prospective anak buah from ‘outside’ could also be adopted as kin, thereby entering this fluid negotiable realm of ‘family’.

Patrons provided (capital-poor) fishers with boats, gear or credit for fishing. In return these fishers (the clients) were obliged to sell (part of) their catch to their patron for a low price. Generally speaking, patrons could keep this price low because dependent fishers were obliged to sell their fish to them to pay off debt. Fish patrons functioned as middlemen (or middlewomen: Pauwelussen 2015) in the fish trade; they sold fish to buyers and markets elsewhere in Indonesia or beyond. In my observation, also independent fishers often engaged with patrons to link up with markets and buyers. Usually, women were actively involved in the performance of patron-client relations, as they were often in charge of credit loans and the recruitment of new anak buah (Schwerdtner Máñez and Pauwelussen 2016).

In Berau, patron-client relations are mostly lifetime or even trans-generational commitments, and options to step out are limited. Obviously, the inequality intrinsic to these relations and the fact that clients are (almost) always ‘in debt’ makes it a potent source of exploitation (Acciaioli 2000; Gaynor 2005). However, these arrangements can also be seen as mutually beneficial (Fabinyi 2013; Ferse et al. 2012). Especially in areas where public services are lacking and rules of law are ambiguous, a patron’s status, support, and resources can safeguard fishers in times of hardship, while the access to credit and fishing appliances offers the means to initiate new income generating activities. Patrons in turn also need their fishers, as the latter form a steady support base for political aspirations as well as a source for cheap labour and resources for the patrons’ businesses (Meereboer 1998). For example, the support by one of Pantai Bakau’s boat-owning patrons for his fishers was returned with support for him to become the new head of the village.

Seeing the act of fishing as mediated through patron-client arrangements places fishing practice in enacted trans-local relations of solidarity and interdependency while also involving exchanges of fish, credit, fuel, tools and daughters in marriage. Maritime patron-client relations often involve inter-island networks of loyalty and debt (Meereboer 1998), and usually extend beyond geographical and administrative boundaries (Adhuri 2013; Visser and Adhuri 2010; Stacey 2007). Their resilience is co-constituted in the association and mobilisation of various elements, such as passports, fish, ice-factories and fish bombs (Pauwelussen 2015). They perform as resilient communities in which (provisional) lines are drawn between ‘us’ and ‘them’, yet stand in an uneasy relation to the community as contained in a village.

‘Community-as-container’ and illegal fishing

As indicated in the introduction, the conservationist alliance in Berau (the Joint Program and the regional fisheries department) aimed to apply a participatory form of marine conservation, in which local communities would be actively involved in conservation practices, to establish a resilient social-ecological seascape. Their programme and practices and to what extent these can be regarded as participatory has been discussed elsewhere (Kusumawati 2014; Kusumawati and Visser 2014), and lies beyond the scope of this article. Here, I indicate first how a ‘container’ version of community translated into the Joint Program's community outreach programme. Secondly, I show how the enactment of the ‘container’ version of community in a community surveillance program was effectively resisted by trans-local community networks.

In the outreach policies of the Joint Program, communities were considered as villages, or a group of villages (Soekirman et al. 2009; Wirjawan et al. 2005). Programmes for community organisation, alternative livelihoods, and enhancing local involvement in conservation practices were thus directed at a community as administrative unit. This affected how outreach practices were organised. During the fieldwork in 2009, Joint Program field staff in Berau carried out field trips and held meetings in coastal villages, including Pantai Bakau. Invitations and organisation for these meetings were run through village government apparatus (as usual - and officially required-in Indonesia). Those occupying a prominent role in village administration, union or public group were commonly present, while fishers, women and patrons were often poorly representedFootnote 6. On their visits to Pantai Bakau, Joint Program staff took along and introduced maps, laws, fingerlings, technologies and ideas to help perform and strengthen the village as a socially resilient community that would act collectively for conservation and against illegal and destructive fishing. To that end, meetings were held to (for example) explain conservation rules, train women how to run microcredit schemes, and establish fish farming in the village as an alternative to fishing.

In the policies and practices of the Joint Program one can observe the enactment of community as primarily based on village administration and geographical position. Pantai Bakau residents (particularly those holding official public positions) recognised and in several ways also participated in this enactment. For example, in my observation (2009–2013) Pantai Bakau village performed as a community in times of elections, during soccer matches, and recently (2013) in formally deciding upon a no-take zone in local waters. In other instances, the village’s internal cohesion and collaboration disassembled into different factions, families and interests, leaving the village’s administrative structure rather bare-boned. This has been particularly the case in the organisation of fishing and fish trade.

The interference of different enactments of solidarity and cohesion in the context of fishing is illustrated by the example of the community-based surveillance (Kelompok Masyarakat untuk Pengawasan Sumberdaya Perikanan dan Kelautan-POKMASWAS) that was set up by the governmental fisheries department in Berau's coastal villages to create a grass-roots network to assist the district government to combat illegal and destructive fishing (Gunawan 2012; Gunawan and Visser 2012). POKMASWAS members (about eight per village) were expected to report to the police and fisheries department any illegal fishing activities they observed at sea while fishing. From the fisheries office, all POKMASWAS groups received tools and technology to carry out this task, among which: binoculars, GPS tracking tools, maps and office supplies to write reports. In Pantai Bakau (as in most villages, in my observation) the programme did not work out as planned: Almost no reports were sent, illegal fishing continued, and the donated tools soon ‘disappeared’. The POKMASWAS members I interviewed found themselves in an awkward position. Some officials to whom the POKMASWAS had to report were known to collaborate with the patrons that ran illegal fishing operations. Also, they themselves had relatives in or outside the village involved in illegal activities. Reporting on family was for most people out of the question. Meanwhile, binoculars and GPS tools had been confiscated by patrons and were used in blast- and cyanide fishing, making these practices more effective and resistant against law enforcement. As Gunawan and Visser (2012) have also pointed out, the POKMASWAS system has been ineffective in combating illegal fishing in Berau, as it cannot cope with a situation in which boundaries of us/them and legal/illegal are permeable and fluid.

The Joint Program’s community outreach and the POKMASWAS programme resonate with common assumptions of local (fishing) communities in institutional approaches to social resilience. Basically, the idea is that local communities need to be strengthened, i.e., made more ‘resilient’, in situ to protect their livelihoods against outside influences. In case fishers engage in illegal fishing, robust and clear institutional arrangements within and among communities should stop the free riders from destroying the common good. Often, illegal fishing is associated with fishers and entrepreneurs from ‘outside’, at the expense of local fishers’ livelihoods, which is reflected in how community surveillance is set up in Berau. The POKMASWAS case shows that how we define ‘social’ units of analysis matters for how marine protection is put into practice, and how this can be ineffective. This particularly applies to cases of marine fishing in which informal distinctions between ‘illegal outsider’ and ‘familiar fisher’ follow relations of sea-based collaboration (St. Martin and Hall-Arber 2008) or the relations of family and debt mentioned earlier. In and around Pantai Bakau blast and cyanide fishers from other villages could claim access to local fishing grounds, provided that ties of familiarity to string-pulling bosses and policemen were actively sustained. The securing of illegal fishing operations through close collaboration with security forces and government officials is significant in this, and observed elsewhere in the region (Adhuri 1998; Fabinyi 2013; Ferse et al. 2012).

Despite high yields, in Berau the use of fish bombs and cyanide rendered many fishers loyal as well as severely indebted to their bosses. Making them change their fishing strategy at sea requires an approach that considers illegal fishing as an enactment of multiple relations that extend beyond village boundaries and simplistic legal/illegal dichotomies. Tracing the lines along which fishing is organised makes clear that an insular approach, focused on local community only, is bound to fail. If definitions of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ are dynamic, relationally constituted and not confined to place, we have to reconsider the idea that local communities need to be made resilient towards external threats, and that external intervention can effectively do so.

Can we perceive of patron-client relations as (community) formations in which social resilience takes form? Yes, clearly. They involve enduring webs of relations, both in terms of providing support and in sustaining inequity (Casson and Obidzinski 2002), while they are contingent on being performed in relational practice. As Broch (2013) has shown in a fisheries context, social resilience requires a certain relational flexibility that extends through different settings. Patron-client networks are particularly elastic and adaptive, shifting to different places, resources and political alignments. They involve senses of belonging, mutual dependency and trust, and as a form of organisation have resisted social-political and economic crises for decades (Acciaioli 2000; Pelras 2000). In connection with illegal and destructive fishing, we can see how they are ‘hard to beat’ for conservationists.

Conclusion

According to John Law (2009), “[M]any sociologies have little sense of how the social is done or holds together” (148). This reflects my concern with how social resilience is conceptualised and applied in the field of fisheries and marine conservation. Working with institutional models of social systems, resilience scholarship has often defined the principles of resilient communities in advance and tested these ‘on the ground’ (Cote and Nightingale 2011). The risk is that if the (modelled) community is not found resilient, one may conclude from an institutional perspective that the community lacks organisational capacity, and should be organised ‘better’ (Cinner et al. 2009; Pinkerton 2009), thereby slipping into a normative mode (Cote and Nightingale 2011). In such cases, practices and relations that do perform resilience are likely overlooked or concealed.

I have therefore proposed to explore and think of communities as performative networks, thereby following a relational ontology associated with ANT, among others. It assumes the social to be an effect of relational practices, by which ‘social’ becomes a dynamic and contingent association of heterogeneous elements. Seeing community as a performative network instead of as a container, resilience is understood as the elasticity or adherence of the (web of) relations rather than the capacity of the container to spring back in shape. I have used the word network as a metaphor that served my purpose to indicate a different way of thinking about social resilience, in which resilience or ‘elasticity’ of community associations is a momentary accomplishment, an outcome of a continuous process of assembling and disassembling relations instead of a property of internal functioning and a buffering capacity against external threats. Tracing communities as performative networks allows for an open-ended, empirical approach that can foreground how, where and in what constellation communities perform in potentially unexpected ways. The study of resilience can then be explored ethnographically by describing how different elements and relations associate into networks that endure.

The point is not that such performative, networked notion of resilience is somehow ‘better’ than a systems perspective. Nor do I wish to argue that a ‘network-community’ is somehow more ‘accurate’ than a ‘container-community’. Instead, I have attempted to point out and illustrate how a different ontological and epistemological approach can complement, and provide critical reflection on, current resilience scholarship. A relational ontological approach, combined with ethnographic fieldwork, can provide vital insights in human-non-human associations that have often remained elusive or beyond the scope of established paradigms.

Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork in the Berau coastal region, I have illustrated how in and beyond the village Pantai Bakau different versions of community were enacted, and how various elements participated in shaping, moving, performing or resisting these. Discussing insights from fieldwork, I have shown how relations of belonging, interdependency, affection and solidarity appeared trans-local, dynamic and sea-oriented rather than confined by geographical or administrative boundaries. Exploring how, where and when maritime communities are enacted allows for a critical reflection on the idea of community as a container of social relations.

Precisely because this container version of community has proven so durable in maritime studies, we need to be critical and sensitive regarding what it can and can’t do in terms of analysis, and what kind of research and policy performances it induces. How we think and conceptualise the social in science and policy has consequences. A preoccupation in (marine) conservation research and policy with the community as village or ‘container’ can lead to a systematic disregard, or even exclusion, of other performances of community, for example those sustaining illegal and destructive fishing and patron-client arrangements. They should not be excluded from empirical investigation just because scientists and policy-makers consider them undesirable. They require attention, because in maritime regions such as in Southeast Asia they form the modus operandi of how fisheries and coastal communities work in practice, and they have successfully resisted interventions for marine conservation.

Implications of a relational approach to community extend beyond the case of illegal fishing. In this article, non-humans were mentioned as merely supporting or constraining the performance of human communities. Another, more symmetric, focus would foreground (for example) the intimate and interdependent relations that fishers sustain with fish or sea spirits (and vice versa) as an enactment of community, or sociality, that transcends human/nature and social/ecological dichotomies, and takes seriously how non-humans continuously affect maritime life.

Ethnographic research, with its rather open-ended approach to navigate complexity can play a vital role in both ontological reflection and empirical grounding of sociological concepts such as community and social resilience. Acknowledging complexity does not necessarily lead to a conclusion that everything is ‘just very complicated’ and leave it at that. On the contrary, by describing practices of relating, moving, interacting, etc., one can show how communities take form, how they sustain or become institutionalised, and how/what participates or interferes. By shifting the focus from how resilient communities should behave, to describing what forms resilient communities do take, ethnographic research can contribute to our understanding of social or community resilience in maritime settings, and beyond.

Notes

Fieldwork was done in Pantai Bakau and beyond, following informants to different places. I also conducted formal and informal interviews with staff of governmental departments, and conservation organisations in Berau, complemented by joining conservation practices and outreach. All names are pseudonyms, including the name of the village.

Thanks to one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing that out.

Based on several conversations with Yurniah throughout the research.

‘Bajau’ is a collective term referring to several marine-oriented and/or sea dwelling ethnic-linguistic groups in South-East Asia (Sather 1997).

In other parts of Indonesia, a difference is made between bos as an intermediate marketer and punggawa as a patron (Acciaioli 2000), however such distinction was not clearly made in Berau.

The Joint Program field staff was aware of this, and at times deliberately invited fish patrons, women and fishers to attend. This attendance should be seen in a context in which women and ‘poor fishers’ are often not expected to join formal/public discussion and decision-making. Perhaps a critical issue here is the very assumption that fisheries is a public matter, whereas fishing and fish trade is often practiced and organised through informal relations.

References

Acciaioli, G. 2000. Kinship and debt: the social organisation of Bugis migration and fish marketing at Lake Lindu, Central Sulawesi. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 156(3): 588–617.

Adger, W.N. 2000. Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Progress in Human Geography 24(3): 347–364.

Adger, W.N., P.M. Kelly, A. Winkels, L.Q. Huy, and C. Locke. 2002. Migration. Remittances, livelihood trajectories, and social resilience. Ambio 31(4): 358–366.

Adger, W.N., T.P. Hughes, C. Folke, S.R. Carpenter, and J. Rockstrom. 2005. Social-ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 209(5737): 1036–1039.

Adhuri, D.S. 1998. Who can challenge them? lessons learned from attempting to curb cyanide fishing in Maluku, Indonesia. SPC Live Reef Fish Information Bulletin 4: 12–17.

Adhuri, D.S. 2013. Traditional and ‘modern’ trepang fisheries on the border of Indonesian and Australian fishing zones. In Makassan history and heritage: journeys, encounters and influences, ed. M.A. Clark and S.K. May, 183–203. Canberra: Anu E Press.

Agrawal, A., and C.C. Gibson. 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development 27(4): 629–649.

Bear, C. 2012. Assembling the Sea: materiality, movement and regulatory practices in the Cardigan Bay scallop fishery. Cultural Geographies 20(1): 21–41.

Béné, C., A. Newsham, M. Davies, M. Ulrichs, and R. Godfrey-Wood. 2014. Review article: resilience, poverty and development. Journal of International Development 26: 598–623.

Berkes, F., and H. Ross. 2013. Community resilience: towards and integrated approach. Society and Natural Resources 26(1): 5–20.

Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke. 2003. Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blanco, G., A. Arce, and E. Fisher. 2015. Becoming a region, becoming global, becoming imperceptible: territorialising salmon in Chilean Patagonia. Journal of Rural Studies 42: 179–190.

Blaser, M. 2009. The threat of the Yrmo: the political ontology of a sustainable hunting program. American Anthropologist. 101(1): 10–20.

Bohle, H.G., B. Etzold, and M. Keck. 2009. Resilience as agency. International Human Dimension Programme Update 2: 8–13.

Broch, H.B. 2013. Social resilience: local responses to changes in social and natural environments. Maritime Studies. doi:10.1186/2212-9790-12-6.

Brosius, J.P., A. Tsing, and C. Zerner. 2005. Communities and conservation: histories and politics of community-based natural resource management. Lanham: Altamira Press.

Callon, M. 1986. Some elements on the sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St. Brieux Bay. In Power, action and belief: a new sociology of knowledge? Sociological review monograph, ed. J. Law, 196–229. London: Routledge.

Casson, A., and K. Obidzinski. 2002. From New Order to regional autonomy: shifting dynamics of “illegal” logging in Kalimantan, Indonesia. World Development 30(12): 2133–2151.

Chou, C. 2003. Indonesian sea nomads: money, magic and fear of the Orang Suku Laut. London: Routledge Curzon.

Cinner, J., M.M.P.B. Fuentes, and H. Randriamahazo. 2009. Exploring resilience in Madagascar's marine protected areas. Ecology and Society 14(1): 41. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art41/.

Cote, M., and A.J. Nightingale. 2011. Resilience thinking meets social theory: situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research. Progress in Human Geography 36(4): 475–489.

Coulthard, S. 2012. Can we be both resilient and well, and what choices do people have? Incorporating agency into the resilience debate from a fisheries perspective. Ecology and Society 17(1): 4. doi:10.5751/ES-04483-170104.

Dwiartama, A., and C. Rosin. 2014. Exploring agency beyond humans: the compatibility of actor-network theory (ANT) and resilience thinking. Ecology and Society 19(3): 28. doi:10.5751/ES-06805-190328.

Eden, S., and C. Bear. 2012. The good, the bad and the hands-on: constructs of public participation, anglers and lay management of water environments. Environment & Planning A 44: 1200–1240.

Fabinyi, M. 2013. Social relations and commodity chains: the live reef fish for food trade. Anthropological Forum 23(1): 36–57.

Fabinyi, M., L. Evans, and S.J. Foale. 2014. Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power: insights from anthropology and political ecology. Ecology and Society 19(4): 28. doi:10.5751/ES-07029-190428.

Ferse, S., L. Knittweis, G. Krause, A. Maddusila, and M. Glaser. 2012. Livelihoods of ornamental coral fishermen in South Sulawesi/Indonesia: implications for management. Coastal Management 40(5): 525–555.

Gaynor, J. 2005. The decline of small-scale fishing and the reorganisation of livelihood practices among Sama people in Eastern Indonesia. Michigan Discussions in Anthropology 15: 90–149.

Grillo, R., and V. Mazzucato. 2008. Africa<>Europe: a double engagement. Journal or Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(2): 175–198.

Gunawan, B.I. 2012. Shrimp fisheries and aquaculture: making a living in the coastal frontier of Berau, Indonesia, PhD thesis. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Gunawan, B.I., and L.E. Visser. 2012. Permeable boundaries: outsiders and access to fishing grounds in the Berau marine protected area. Anthropological Forum 22(2): 187–207.

Healey, M. 2009. Resilient salmon, resilient fisheries for British Columbia, Canada. Ecology and Society 14(1):2. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art2/.

IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (IUCN-WCPA). 2008. Establishing resilient marine protected area networks: making it happen. Washington D.C.: IUCN-WCPA.

Janssen, M.A., Ö. Bodin, J.M. Anderies, T. Elmqvist, H. Ernstson, R.R.J. Mcallister, P. Olsson, and P. Ryan. 2006. Toward a network perspective of the study of resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 11(1): 15. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art15/.

Jentoft, S. 2000. The community: a missing link of fisheries management. Marine Policy 24: 53–59.

Johnson, C. 2001. Community formation and fisheries conservation in Southern Thailand. Development and Change 32: 951–974.

Kusumawati, R. 2014. Networks and knowledge at the interface: governing the coast of East Kalimantan, Indonesia, PhD Thesis. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Kusumawati, R., and L.E. Visser. 2014. Collaboration or contention? Decentralised marine governance in Berau. Anthropological Forum 24(1): 21–46.

Kusumawati, R., S.R. Bush, and L.E. Visser. 2013. Can patrons be bypassed? Frictions between local and global regulatory networks over shrimp aquaculture in East Kalimantan. Society & Natural Resources 26(8): 898–911.

Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Law, J. 1986. On the methods of long distance control: vessels, navigation, and the Portuguese route to India. In Power, action and belief: a new sociology of knowledge? Sociological review monograph, ed. J. Law, 234–263. London: Routledge.

Law, J. 2009. Actor network theory and material semiotics. In The New Blackwell companion to social theory, ed. B.S. Turner, 141–158. Chicester: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Law, J., and M. Lien. 2013. Slippery: field notes in empirical ontology. Social Studies of Science 43: 363–378.

Li, T. 1996. Images of community: discourse and strategy in property relations. Development and Change 27(3): 501–527.

López-Marrero, T., and P. Tschakert. 2011. From theory to practice: enhancing resilience to floods in exposed communities. Environment and Urbanization 23: 1–21.

Lowe, C. 2003. The magic of place: Sama at Sea and on land in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159(1): 109–133.

Malkki, L. 1992. National geographic: the rooting of peoples and the territorialization of national identity among scholars and refugees. Cultural Anthropology 7(1): 24–44.

Marín, A., and F. Berkes. 2010. Network approach for understanding small-scale fisheries governance: the case of the Chilean coastal co-management system. Marine Policy 34(5): 851–858.

Meereboer, M.T. 1998. Fishing for credit: patronage and debt relations in the Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. In Living through histories: culture, history and social life in South Sulawesi, ed. K. Robinson and M. Paeni, 249–276. Canberra: ANU/RSPAS.

Moore, A. 2012. The aquatic invaders: marine management figuring fishermen, fisheries, and lionfish in the Bahamas. Cultural Anthropology 27(4): 667–688.

Pauwelussen, A.P. 2015. The moves of a Bajau middlewomen: understanding the disparity between trade networks and marine conservation. Anthropological Forum 25(4): 329–349.

Pelras, C. 2000. Patron-client ties among the Bugis and Makassarese of South Sulawesi. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 156(3): 393–432.

Pinkerton, E. 2009. Coastal marine systems: conserving fish and sustaining community livelihoods with co-management. In Principles of ecosystem stewardship, ed. F.S. Chapin, G.P. Kofinas, and C. Folke, 241–257. New York: Springer.

Pitchon, A. 2011. Sea hunters or sea farmers? Transitions in Chilean fisheries. Human Organisation 70(2): 200–209.

Ratner, B.D., and E.H. Allison. 2012. Wealth, rights, and resilience: an agenda for governance reform in small-scale fisheries. Development Policy Review 30(4): 371–398.

Sather, C. 1997. The Bajau Laut. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sather, C. 2002. Commodity trade, gift exchange, and the history of maritime nomadism in Southeastern Sabah. Nomadic Peoples 6(1): 20–44.

Schwerdtner Máñez, K., and A.P. Pauwelussen. 2016. Fish is Women’s business too: looking at marine resource use through a gender lens. In Perspectives on oceans past: a handbook of marine environmental history, ed. K. Schwerdtner Máñez and B. Poulsen. New York: Springer Publishers.

Soekirman, T., E. Carter, H. Widodo, and M. Scherl. 2009. Community development and alternative livelihood initiatives at TNC-Coral Triangle Centre related sites. Bali: The Nature Conservancy.

St. Martin, K., and M. Hall-Arber. 2008. Creating a place for ‘community’ in New England fisheries. Human Ecology Review 15(2): 161–170.

Stacey, N. 2007. Boats to burn: Bajo fishing activity in the Australian fishing zone. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Tagliacozzo, E. 2009. Navigating communities: race, place, and travel in the history of maritime Southeast Asia. Asian Ethnicity 10(2): 97–120.

Visser, L.E., and D.S. Adhuri. 2010. Territorialization re-examined: transborder marine resources exploitation in Southeast Asia and Australia. In Transborder governance of forests, rivers and seas, ed. W. de Jong, D. Snelder, and N. Ishikawa, 83–98. London: Earthscan.

Viveiros de Castro, E. 2003. Manchester Papers in Social Anthropology 7. Speech given at the 5th Decennial Conference of the Association of Social Anthropologists of Great Britain and Commonwealth, 14 July 2003. https://sites.google.com/a/abaetenet.net/nansi/abaetextos/anthropology-and-science-e-viveiros-de-castro (consulted 20 January 2016).

Warren, J. 2007. The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast-Asian maritime state. 2nd ed. Singapore: NUS Press.

Wilson, J., P.J. Mous, B. Wirjawan, and L.M. DeVantier. 2010. Report on a rapid ecological assessment of the Derawan Islands, Berau district, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, October 2003. Bali: The Nature Conservancy.

Wirjawan, B., M. Khazali, and M. Knight. 2005. Menuju Kawasan Konservasi Laut Berau, Kalimantan Timur: Status Sumberdaya Pesisir dan Proses Pengembangan. Jakarta: Program Bersama Kelautan Berau TNC-WWF-Mitra Pesisir/CRMP II USAID.

Zerner, C. 2003. Sounding the Makassar Strait: the poetics and politics of an Indonesian marine environment. In Culture and the question of rights, ed. C. Zerner, 56–108. Durham: Duke University Press.

Acknowledgement

I gratefully acknowledge the valuable feedback and support of Leontine Visser for the writing of this paper and throughout the research process. Thanks also to Vincent de Rooij, Jacco Hupkens and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The research was partly funded by the Wageningen School of Social Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Authors’ information

Annet Pauwelussen is a PhD candidate at the Sociology of Development and Change group , Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pauwelussen, A. Community as network: exploring a relational approach to social resilience in coastal Indonesia. Maritime Studies 15, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-016-0041-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-016-0041-5