Abstract

Background

This study was conducted to investigate effect of exogenous melatonin on the development of mouse mature oocytes after cryopreservation.

Results

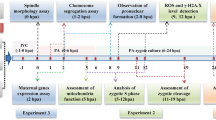

First, mouse metaphase II (MII) oocytes were vitrified in the open-pulled straws (OPS). After warming, they were cultured for 1 h in M2 medium containing melatonin at different concentrations (0, 10−9, 10−7, 10−5, 10−3 mol/L). Then the oocytes were used to detect reactive oxygen species (ROS) and glutathione (GSH) levels (fluorescence microscopy), and the developmental potential after parthenogenetic activation. The experimental results showed that the ROS level and cleavage rate in 10−3 mol/L melatonin group was significantly lower than that in melatonin-free group (control). The GSH levels and blastocyst rates in all melatonin-treated groups were similar to that in control. Based on the above results, we detected the expression of gene Hsp90aa1, Hsf1, Hspa1b, Nrf2 and Bcl-x1 with qRT-PCR in oocytes treated with 10−7, or 10−3 mol/L melatonin and untreated control. After warming and culture for 1 h, the oocytes showed higher Hsp90aa1 expression in 10−7 mol/L melatonin-treated group than in the control (P < 0.05); the Hsf1, Hsp90aa1 and Bcl-x1 expression were significantly decreased in 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group when compared to the control. Based on the above results and previous research, we detected the development of vitrified-warmed oocytes treated with either 10−7 or 0 mol/L melatonin by in vitro fertilization. No difference was observed between them.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the supplementation of melatonin (10−9 to 10−3 mol/L) in culture medium and incubation for 1 h did not improve the subsequent developmental potential of vitrified-warmed mouse MII oocytes, even if there were alteration in gene expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as a part of normal cellular metabolism and as a consequence of exogenous administered molecules [1], play an important role as second messengers in cellular functions through activation of cell signaling cascades, such as those involving in mitogen-activated protein kinases and regulation of transcription factors. Excessive ROS, however, are highly reactive with complex cellular molecules (proteins, lipids, and DNA) and may change their functions [2]. This may lead to serious consequences, for instance, enzymatic inactivation, DNA fragmentation, and ultimately cell death [3–6]. Glutathione (GSH) is a major antioxidant acting as a free radical scavenger that protects the cell from ROS. The balance between ROS and GSH had been considered in controlling the oocyte maturation and the normal development of zygotes [7, 8]. During cryopreservation, oocytes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress because of the high level of lipid, generating large amount of ROS [9], which influence the balance between the oxidation–reduction reactions and the intracellular antioxidative system. An imbalance in this system in the favor of oxidation significantly reduced cell viability [10].

Transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2) participates in the transcription regulation of enzyme which was involved in the GSH synthesis metabolism [11], consequently regulating the balance of ROS/GSH [12]. Transcription factor Hsf1 (heat shock factor 1) was involved in both the regulation of the balance of ROS/GSH and the transcription of Hsp90 and Hsp70. Heat shock proteins (HSP), a set of proteins generated under stress, were associated with RNA processing, RNP assembly, and chromatin remodeling [13], and among them, maternal Hsp90 and Hsp70 were required for the embryonic development [14–17]. Transcription factors Hsf1 and Nrf2 engaged in crosstalk for cytoprotection by sharing overlapping transcriptional targets, such as HSP70 [11]. After oocytes cryopreservation, the expression of Hsp70 [18] and Hsp90β [19] was significantly decreased, potentially influencing their subsequent development potential.

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), a derivative of tryptophan mainly produced in the pineal gland of vertebrates [20, 21], is a potent free radical scavenger and antioxidant [22, 23]. Melatonin and its metabolites could directly scavenge ROS, stimulate antioxidative enzymes, increase the levels of GSH, inhibit the pro-oxidative enzymes in cells and organs [24–26], and promote the expression of antiapoptotic gene Bcl-xl [27]. When melatonin was added to semen extender or culture medium, the sperm viability, oocyte competence and blastocyst development in vitro were significantly improved (reviewed by [23]). However, it is still unclear whether or not the oocyte development could be improved by the addition of melatonin to the medium for in vitro culture of vitrified-warmed mouse metaphase II (MII) oocytes.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effect of melatonin on developmental potential of vitrified mouse oocytes, including detecting ROS and GSH levels, expressions of apoptosis related genes (Hsp90aa1, Hsf1, Hspa1b, Nrf2 and Bcl-x1), subsequent embryonic development after parthenogenetic activation and in vitro fertilization.

Materials and methods

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All animals were maintained and handled in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the China Agricultural University.

Oocyte collection

Outbred female Kun Ming mice (different from the typical inbred strains [28]) (China Experimental Animal Center of Military Medical Sciences, China) aged 6 wk were kept in a room with the temperature controlled at 20–22 °C under a 14:10 light/dark cycle (light on at 06:00 h). After a week of acclimation, female mice were induced to superovulate by an intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin initially, and 48 h later, 10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) was injected to trigger ovulation, as described previously [29]. Cumulus–oocyte complexes were collected from oviducts at 14 h after hCG treatment and recovered in M2 medium [30] supplemented with 3 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. Cumulus cells were dispersed with 300 IU/mL hyaluronidase.

Vitrification and warming of oocytes

The open-pulled straws (OPS) were made according to the method as described previously [31, 32] with some modifications. Briefly, the straws (250 mL; IMV, L’Aigle, France) were heat-softened and pulled manually to get a straw of approximately 2 to 3 cm in length, 0.10 mm in inner diameter, and 0.15 mm in outer diameter.

Oocytes were vitrified using an OPS method. Oocytes were first equilibrated in 10 % ethylene glycol (EG) + 10 % dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) containing 20 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone; Gibco BRL, Paisley, Scotland, UK) for 30 s, then loaded into the narrow end of OPS with EDFS30 solution which consisted of DPBS medium containing 300 g/L Ficoll, 0.5 mol/L sucrose, and 20 % FBS, 15 % (v/v) EG and 15 % (v/v) DMSO, for 25 s. Finally, the straws containing oocytes (10 oocytes per OPS) were plunged into liquid nitrogen. When warming, oocytes were rinsed in 0.5 mol/L sucrose for 5 min, then washed 3 times in M2 medium and incubated in a CO2 incubator for 1 h in M2 medium with different concentration of melatonin. All manipulations were performed at 37 °C on a warming stage fixed on the stereomicroscope, and the ambient atmosphere was air-conditioned at a temperature of 25 ± 0.5 °C. Oocytes were pooled and randomly distributed to each group.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species and glutathione levels

Mouse MII oocytes were sampled to determine the intracellular ROS and GSH levels according to the method described in previous study [33]. To measure intracellular ROS level, more than 15 oocytes from each treatment group were incubated (in the dark) in M2 supplemented with 1 mmol/L 20,70-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) for 20 min at 37 °C, washed three times with DPBS containing 0.1 % (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol, and then placed into 50 mL droplets. The fluorescence was measured under an epifluorescence microscope with a filter at 460-nm excitation, and fluorescence images were recorded as TIFF files using a cooled CCD camera (DP72, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The recorded fluorescence intensities were quantified by EZ-C1 Free Viewer software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The level of GSH in each oocyte was measured with 10 μmol/L 4-chloromethyl-6.8-difluoro-7-hydroxycoumarin (Cell-Tracker Blue) with a filter at 370-nm excitation. The experimental procedure was the same as the ROS measurement described above.

Oocyte activation and embryo culture

All treated oocytes were allowed to recover in a CO2 incubator for 1 h before activation. The activation medium used was Ca2+-free human tubal fluid (HTF) [34] supplemented with 10 mmol/L SrCl2 [35]. After being washed thrice in activation medium, oocytes were incubated first in activation medium for 2.5 h and then in regular HTF without SrCl2 for 3.5 h at 37.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2 in air. Both the activation medium and HTF for subsequent short culture of oocytes were supplemented with 2 μg/mL cytochalasin D. Six h after the onset of activation, oocytes were removed from the medium and cultured in KSOM-AA (simplex optimized medium contained K ions supplemented with amino acids) medium [36] (Millipore) for 4 d. Embryos at the two cell and blastocyst stages were examined and recorded at 24, and 96 h after start of culture in KSOM-AA medium, respectively.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction(Q-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from 50 mouse oocytes for each group by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA(cDNA) using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA); then, the cDNA was quantified by Q-PCR using a SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) under standard conditions. The cycle threshold (Ct) value used to calculate the relative expression was the average of three replicates and was normalized against that of the reference gene (GAPDH). The primer information was summarized in Table 1. The mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2-△△Ct method [37].

In vitro fertilization (IVF)

The fresh and vitrified-warmed oocytes were first individually placed into 70 μL drops of human tubal fluid (HTF) medium (Millipore) under mineral oil, then 10 μL of capacitated sperm, which had been incubated for 1–1.5 h in HTF medium in a CO2 incubator, was added to the oocytes. The final concentration was 2.0-6.0 × 106 sperm/mL. Five h after IVF, the oocytes were removed from the fertilization drops, washed in KSOM-AA medium (Millipore) 3 times, and cultured in 70 μL drops of KSOM-AA medium. Embryos at the two-cell and blastocyst stages were examined and recorded at 24, and 96 h after start of culture in KSOM-AA medium, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test using SPSS statistical software (IBM, IL, USA). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of melatonin on redox state in vitrified-warmed mouse mature oocytes

After warming, mouse MII oocytes were cultured for 1 h in M2 medium containing different concentrations (0, 10−9, 10−7, 10−5, 10−3 mol/L) of melatonin, respectively. Then the oocytes were used for detection of ROS and GSH levels. As shown in Fig. 1, the ROS level was lower (P < 0.05) in 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group than in melatonin-free group (control), and the GSH level in melatonin-treated groups showed no significant difference (P > 0.05) when compared with control group.

Effects of melatonin on intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and glutathione (GSH) in vitrified-warmed mouse oocytes. Fluorescence intensities were correlated with intracellular levels of ROS and GSH. Number of Oocytes in each group (n). a and b denote significant differences (P < 0.05)

Effect of melatonin on parthenogenetic development of vitrified-warmed mouse metaphase II oocytes

As shown in Table 2, when vitrified-warmed mouse MII oocytes were cultured for 1 h in M2 medium with different concentrations (0, 10−9, 10−7, 10−5, 10−3 mol/L) of melatonin, respectively, followed by parthenogenetic activation, the cleavage rate decreased significantly in 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group when compared with control group, but the blastocyst rate in all melatonin-treated groups was similar to (P > 0.05) that in control group.

Effect of melatonin on genes expression in vitrified-warmed mouse metaphase II oocytes

As shown in Fig. 2, when vitrified-warmed mouse MII oocytes were cultured for 1 h in M2 medium with different concentrations (0, 10−7, 10−3 mol/L) of melatonin, respectively, the expressions of Hsp90aa1, Hsf1, Hspa1b, Nrf2 and Bcl-x1 were decreased in the 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group when compared with the other two groups. But the expressions of Hsf1, Hsp90aa1 and Bcl-x1 in the 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group were lower than those in the melatonin-free group (P < 0.05). Compared with the melatonin-free group, the 10−7 mol/L melatonin-treated group showed decreased expressions in genes Hsf1 and Hspa1b, increased expression in genes Hsp90aa1, Nrf2 and Bcl-x1, and significantly increased (P < 0.05) expression in gene Hsp90aa1 .

Effect of melatonin on subsequent embryonic development after IVF

As shown in Table 3, when vitrified-warmed mouse MII oocytes were cultured for 1 h in M2 medium with different concentrations (0 and 10−7 mol/L) of melatonin, respectively, followed by IVF. The fresh mouse MII oocytes were used as control. Either the cleavage or the blastocyst rates in both the melatonin-treated and melatonin-free groups were similar, but they were significantly lower (P < 0.05) when compared with the fresh control group.

Discussion

Mammalian oocytes with complicated subcellular structure are sensitive to the temperature and osmotic pressure changes [38]. During cryopreservation, changes could occur in the microenvironment of the oocytes, such as the formation and release of large amounts of ROS [9], consequently influencing the quality of oocytes [39]. The excessive ROS production due to oocyte cryopreservation could disturb the balance between the oxidation-reduction reaction and the antioxidant system, and would lead to reduced cell viability [10]. Nakano and his coworkers found that overproduction of ROS can be removed by adding melatonin into oocytes culture medium [40], and the development of oocytes could be improved [41, 42]. In the present study, the excessive ROS production in mouse oocytes due to cryopreservation could also be decreased by addition of melatonin to the culture medium. The mechanism of melatonin scavenging ROS is consistent with that of other antioxidants [43, 44].

Only when the melatonin concentration was within proper limits can it promote the development of oocyte and embryo either by scavenging the excessive ROS as described above, or by regulating gene expression through transcriptional factor Nrf2 [45]. Glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit (Gclm) could be regulated by Nrf2, and when expression of gene Gclm changes in oocytes, the GSH synthesis will be influenced. The decreased GSH level in oocytes [8] as well as the deficiency of the Nrf2 and Nrf1 transcription factors could result in early embryonic lethality [46]. In the present study, no significant change was observed in either the Nrf2 expression or the GSH level after melatonin addition into the culture medium. Similarly the blastocyst rate of vitrified-warmed mouse oocytes after parthenogenetic activation was not affected by melatonin treatment.

However, when the melatonin concentration in the culture medium was beyond the proper limits, it may not show positive effect on the development of oocyte and embryo. In mouse, melatonin increased the IVF rate significantly at a concentration between 10−6 and 10−4 mol/L [47]; while at 10−3 mol/L, it significantly retarded the blastocyst rate [48]. In bovine, most effective melatonin concentrations ranged from 10−9 to 10−7 mol/L; while at 10−5 mol/L, it showed similar rates of cleavage and blastocyst to the control [49]. Similar results have been obtained in this study; when 10−3 mol/L melatonin was added into the culture medium, the cleavage rate of vitrified-warmed mouse mature oocytes after parthenogenetic activation, the expression of Hsf1, Hsp90 and Bcl-x1 was significantly decreased, but the blastocyst rate was similar to the control. In a word, it seemed that the melatonin has different effects on the development of embryos, depending on the concentrations [42, 50] and culture conditions [40, 51]. The length of time that oocytes were exposed to exogenous melatonin could also influence the development of embryos [27, 51]. Addition of melatonin into the medium in the whole process of culture, for instance, showed a positive effect on embryonic development in mice [47], sheep and goat [52, 53], pigs [27] and buffalo [54]. In the present study, the incubation time for culture of vitrified-warmed mouse oocytes in M2 medium with melatonin was only 1 h. In such a short period of time, the melatonin at the concentration range of 10−5-10−9 mol/L could not improve the rates of cleavage and blastocyst. It seemed that the culture time in M2 medium with melatonin should be prolonged.

Conclusion

To sum up, ROS level was significantly decreased in 10−3 mol/L melatonin-treated group compared with the other concentration and groups, and the expression of Hsp90aa1 increased significantly in 10−7 mol/L melatonin-treated group. GSH level, rates of cleavage and blastocyst development of oocytes after parthenogenetic activation and IVF were similar between the melatonin-treated and melatonin-free groups. Therefore, the addition of melatonin into the culture medium in the present study showed no positive effect on the subsequent development of vitrified-warmed mouse MII oocytes, even if there were alteration in gene expression.

Abbreviations

- 10 % EG + 10 % DMSO:

-

10 % (v/v) ethylene glycol and 10 % (v/v) Dimethyl Sulphoxide in DPBS

- EFS30:

-

DPBS medium containing 30 % (v/v) ethylene glycol, 21 % (w/v) Ficoll 70, and 0.35 mol/L sucrose

- IVF:

-

in vitro fertilization

- V:

-

Volume

References

Fujimoto VY, Bloom MS, Huddleston HG, Shelley WB, Ocque AJ, Browne RW. Correlations of follicular fluid oxidative stress biomarkers and enzyme activities with embryo morphology parameters during in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(6):1357–61. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.032.

Goud AP, Goud PT, Diamond MP, Gonik B, Abu-Soud HM. Reactive oxygen species and oocyte aging: Role of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(7):1295–304. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.014.

Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3(28):1–21.

Favetta LA, St John EJ, King WA, Betts DH. High levels of p66shc and intracellular ROS in permanently arrested early embryos. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(8):1201–10. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.018.

Banerjee J, Maitra D, Diamond MP, Abu-Soud HM. Melatonin prevents hypochlorous acid-induced alterations in microtubule and chromosomal structure in metaphase-II mouse oocytes. J Pineal Res. 2012;53(2):122–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00977.x.

Khalil WA, Marei WFA, Khalid M. Protective effects of antioxidants on linoleic acid–treated bovine oocytes during maturation and subsequent embryo development. Theriogenology. 2013;80(2):161–8. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.04.008.

Luberda Z. The role of glutathione in mammalian gametes. Reprod Biol. 2005;5(1):5–17.

Nakamura BN, Fielder TJ, Hoang YD, Lim J, McConnachie LA, Kavanagh TJ, et al. Lack of maternal glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit (Gclm) decreases oocyte glutathione concentrations and disrupts preimplantation development in mice. Endocrinology. 2011;152(7):2806–15.

Somfai T, Ozawa M, Noguchi J, Kaneko H, Kuriani Karja NW, Farhudin M, et al. Developmental competence of in vitro-fertilized porcine oocytes after in vitro maturation and solid surface vitrification: Effect of cryopreservation on oocyte antioxidative system and cell cycle stage. Cryobiology. 2007;55(2):115–26.

De Leon PMM, Campos VF, Corcini CD, Santos ECS, Rambo G, Lucia Jr T, et al. Cryopreservation of immature equine oocytes, comparing a solid surface vitrification process with open pulled straws and the use of a synthetic ice blocker. Theriogenology. 2012;77(1):21–7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.07.008.

Naidu SD, Kostov RV, Dinkova-Kostova AT. Transcription factors Hsf1 and Nrf2 engage in crosstalk for cytoprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(1):6–14.

Amin A, Gad A, Salilew‐Wondim D, Prastowo S, Held E, Hoelker M, et al. Bovine embryo survival under oxidative‐stress conditions is associated with activity of the NRF2‐mediated oxidative‐stress‐response pathway. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81(6):497–513.

Hartson SD, Matts RL. Approaches for defining the Hsp90-dependent proteome. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular. Cell Res. 2012;1823(3):656–67.

Metchat A, Åkerfelt M, Bierkamp C, Delsinne V, Sistonen L, Alexandre H, et al. Mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for oocyte meiosis and directly regulates Hsp90α expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9521–8.

Audouard C, Le Masson F, Charry C, Li Z, Christians ES. Oocyte–Targeted Deletion Reveals That Hsp90b1 Is Needed for the Completion of First Mitosis in Mouse Zygotes. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17109.

Christians E, Davis A, Thomas S, Benjamin I. Embryonic development: maternal effect of Hsf1 on reproductive success. Nature. 2000;407(6805):693–4.

Le Masson F, Christians E. HSFs and regulation of Hsp70. 1 (Hspa1b) in oocytes and preimplantation embryos: new insights brought by transgenic and knockout mouse models. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2011;16(3):275–85.

Jahromi ZK, Amidi F, Mugehe SMHN, Sobhani A, Mehrannia K, Abbasi M, et al. Expression of heat shock protein (HSP A1A) and MnSOD genes following vitrification of mouse MII oocytes with cryotop method. Yakhteh Med J. 2010;12(1):113–9.

Succu S, Bebbere D, Bogliolo L, Ariu F, Fois S, Leoni GG, et al. Vitrification of in vitro matured ovine oocytes affects in vitro pre‐implantation development and mRNA abundance. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75(3):538–46.

Reiter R. Tan D-x, Osuna C, Gitto E. Actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7(6):444–58. doi:10.1007/BF02253360.

Siu AW, Maldonado M, Sanchez‐Hidalgo M, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Protective effects of melatonin in experimental free radical‐related ocular diseases. J Pineal Res. 2006;40(2):101–9.

Reiter RJ. Melatonin: Lowering the high price of free radicals. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15:246–50.

Cruz MHC, Leal CLV, da Cruz JF, Tan D-X, Reiter RJ. Role of melatonin on production and preservation of gametes and embryos: a brief review. Anim Reprod Sci. 2014;145(3):150–60.

Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin as a natural ally against oxidative stress: a physicochemical examination. J Pineal Res. 2011;51(1):1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00916.x.

Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin's metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J Pineal Res. 2013;54(3):245–57. doi:10.1111/jpi.12010.

Hardeland R. Melatonin and the theories of aging: a critical appraisal of melatonin's role in antiaging mechanisms. J Pineal Res. 2013;55(4):325–56.

Rodriguez-Osorio N, Kim IJ, Wang H, Kaya A, Memili E. Melatonin increases cleavage rate of porcine preimplantation embryos in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2007;43(3):283–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00475.x.

Zhang X, Zhu Z, Huang Z, Tan P, Ma RZ. Microsatellite genotyping for four expected inbred mouse strains from KM mice. J Gen Genom. 2007;34(3):214–22.

Wang L, Liu J, Zhou G-B, Hou Y-P, Li J-J, Zhu S-E. Quantitative investigations on the effects of exposure durations to the combined cryoprotective agents on mouse oocyte vitrification procedures. Biol Reprod. 2011;85(5):884–94.

Whittingham D. Culture of mouse ova. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1971;14:7–21.

Vajta G, Kuwayama M, Holm P, Booth P, Jacobsen H, Greve T, et al. A new way to avoid cryoinjuries of mammalian ova and embryos: the OPS vitrification. Mol Reprod Dev. 1998;51(1):53–8.

Yan C-L, Fu X-W, Zhou G-B, Zhao X-M, Suo L, Zhu S-E. Mitochondrial behaviors in the vitrified mouse oocyte and its parthenogenetic embryo: effect of Taxol pretreatment and relationship to competence. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):959–66.

Wu GQ, Jia BY, Li JJ, Fu XW, Zhou GB, Hou YP, et al. L-carnitine enhances oocyte maturation and development of parthenogenetic embryos in pigs. Theriogenology. 2011;76(5):785–93. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.04.011.

Quinn P, Kerin J, Warnes G. Improved pregnancy rate in human in vitro fertilization with the use of a medium based on the composition of human tubal fluid. Fertil Steril. 1985;44(4):493–8.

Carbone M, Tatone C. Alterations in the protein kinase C signaling activated by a parthenogenetic agent in oocytes from reproductively old mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76(2):122–31.

Ho Y, Wigglesworth K, Eppig JJ, Schultz RM. Preimplantation development of mouse embryos in KSOM: augmentation by amino acids and analysis of gene expression. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;41(2):232–8.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8.

Vajta G, Kuwayama M. Improving cryopreservation systems. Theriogenology. 2006;65(1):236–44.

Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Korkmaz A, Manchester LC, Tan D-X, Sugino N, et al. Melatonin and the ovary: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(1):328–43. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.016.

Nakano M, Kato Y, Tsunoda Y. Effect of melatonin treatment on the developmental potential of parthenogenetic and somatic cell nuclear-transferred porcine oocytes in vitro. Zygote. 2012;20(2):199–207.

Kang J-T, Koo O-J, Kwon D-K, Park H-J, Jang G, Kang S-K, et al. Effects of melatonin on in vitro maturation of porcine oocyte and expression of melatonin receptor RNA in cumulus and granulosa cells. J Pineal Res. 2009;46(1):22–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00602.x.

Shi J-M, Tian X-Z, Zhou G-B, Wang L, Gao C, Zhu S-E, et al. Melatonin exists in porcine follicular fluid and improves in vitro maturation and parthenogenetic development of porcine oocytes. J Pineal Res. 2009;47(4):318–23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00717.x.

Hardeland R. Atioxidative protection by melatonin. Endocrine. 2005;27(2):119–30. doi:10.1385/ENDO:27:2:119.

León J, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Escames G, Tan D-X, Reiter RJ. Melatonin mitigates mitochondrial malfunction. J Pineal Res. 2005;38(1):1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00181.x.

Korkmaz A, Rosales-Corral S, Reiter RJ. Gene regulation by melatonin linked to epigenetic phenomena. Gene. 2012;503(1):1–11. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.04.040.

Leung L, Kwong M, Hou S, Lee C, Chan JY. Deficiency of the Nrf1 and Nrf2 transcription factors results in early embryonic lethality and severe oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(48):48021–9.

Ishizuka B, Kuribayashi Y, Murai K, Amemiya A, Itoh MT. The effect of melatonin on in vitro fertilization and embryo development in mice. J Pineal Res. 2000;28(1):48–51. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079x.2000.280107.x.

Wang F, Tian XZ, Zhang L, Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Liu GS. Melatonin promotes the in vitro development of pronuclear embryos and increases the efficiency of blastocyst implantation in murine. J Pineal Res. 2013;55(3):267–74. doi:10.1111/jpi.12069.

Wang F, Tian X, Zhang L, Gao C, He C, Fu Y, et al. Beneficial effects of melatonin on in vitro bovine embryonic development are mediated by melatonin receptor 1. J Pineal Res. 2014;56(3):333–42. doi:10.1111/jpi.12126.

Manjunatha BM, Devaraj M, Gupta PSP, Ravindra JP, Nandi S. Effect of taurine and melatonin in the culture medium on buffalo in vitro embryo development. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44(1):12–6. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00982.x.

Kim MK, Park EA, Kim HJ, Choi WY, Cho JH, Lee WS, et al. Does supplementation of in-vitro culture medium with melatonin improve IVF outcome in PCOS? Reproductive Biomed Online. 2013;26(1):22–9. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.10.007.

Abecia JA, Forcada F, Zúñiga O. The effect of melatonin on the secretion of progesterone in sheep and on the development of ovine embryos in vitro. Vet Res Commun. 2002;26(2):151–8. doi:10.1023/A:1014099719034.

Berlinguer F, Leoni GG, Succu S, Spezzigu A, Madeddu M, Satta V, et al. Exogenous melatonin positively influences follicular dynamics, oocyte developmental competence and blastocyst output in a goat model. J Pineal Res. 2009;46(4):383–91. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00674.x.

Sampaio RV, Conceição S, Miranda MS, Sampaio Lde F, Ohashi OM. MT3 melatonin binding site, MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are present in oocyte, but only MT1 is present in bovine blastocyst produced in vitro. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:103.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National genetically modified organisms breeding major projects (Grant No. 2014ZX0800802B) and the fund for Backup Candidate of Academic Technology Leaders in Sichuan Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LW carried out the experiment (design), data interpretation and manuscript writing. CKR participated in the culture of oocytes and embryos. ZY participated in manuscript writing. MQG proofed the manuscript. ZSE participated in discussion. ZGB participated in data interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Li Wei1,4 is Master Degree Candidate of College of Animal Science and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University (Chengdu Campus). Keren Cheng2 is Ph.D candidate of College of Animal Science and Technology, China Agricultural University. Yue Zhang1 is Master Degree Candidate of College of Animal Science and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University (Chengdu Campus). Qinggang Meng3 is professor of Department of Animal, Dairy, and Veterinary Sciences, Utah State University, Logan, Utah. Shi-en Zhu2 is professor of Animal Science and Technology, China Agricultural University. Guangbin Zhou1,* is professor of College of Animal Science and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University (Chengdu Campus).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Cheng, K., Zhang, Y. et al. No effect of exogenous melatonin on development of cryopreserved metaphase II oocytes in mouse. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 6, 42 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-015-0041-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-015-0041-0