Abstract

The periodic reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are announced each time by a strategic document in the form of a Communication by the European Commission (EC). The content of the last Communication differs from previous ones, which raises the questions of what frames the EC has employed with respect to its CAP reforms and how these frames have been modified over the past 26 years (from 1991 to 2017) in order to legitimise the preservation of the CAP. This paper tries to fill the gap in the research of frames in the main strategic documents on the CAP by employing comparative historical framing analysis. The results show consistent use of five frames: the policy mechanism frame, farmers’ economic frame, foreign trade frame, budgetary frame, and the societal concerns frame. While they have all remained in use, most have been changed significantly over the years. Throughout the analysed period, the farmers’ economic frame has retained its primacy and continuity, demonstrating the power of the farmers’ lobbies and conservative member states. If in the initial Communications the environment was barely present within the societal concerns frame, it has gained importance in the recent Communications, in addition to other general societal issues, such as climate change, food security and quality, health, digitalisation, innovation, and even migration. By marginalising the policy mechanism frame and replacing it with the implementation model and increasingly emphasising the societal concerns frame with social justifications of the CAP, the EC is trying to legitimise the CAP after 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since every policy issue has numerous aspects, the process of selecting and highlighting a particular feature of an issue, i.e. framing, is a key process in policy debate, as stated by framing theory (Baumgartner and Mahoney 2008; Daviter 2009; Eising et al. 2015). Political actors involved in the European Union (EU) policy debates change terms of the debates and ultimately affect legislative outcomes by framing proposals strategically (Ringe 2005, 2010; Daviter 2011). Policy proposals are a result of strategic decisions based on choices of frames presented in policy debates by interest groups that deliberately highlight certain aspects of policy proposals in order to gain advantage (Klüver et al. 2015). Since the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one of the most complex and controversial EU policies and one that comprises a significant share of the total EU budget, it is crucial to systematically study what frames the EC constructs with respect to its CAP reforms in order to legitimise its preservation.

In line with established practice, each reform of the CAP is announced by a strategic document in the form of a Communication published by the European Commission (EC), setting out the content of the reform. As the Communications represent strategic documents of the CAP, it is important to examine how they have been framed over time. Historically, the CAP has shifted its focus away from market price and production support, which resulted in trade distortions and subsequent conflicts in international trade, and controversies related to excessive budgetary spending and to societal concerns, such as environmental protection, food and public health concerns, and climate change (Garzon et al. 2006; Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2011).

Frame analysis is a useful tool for the analysis of policy proposals (Ringe 2005, 2010; Daviter 2009, 2011; Eising et al. 2015; Klüver et al. 2015)—in our case, the EC’s Communications—to answer the research question: What are the transformations of frames throughout the history of CAP reforms? Analysis of the EC’s CAP Communications over the past 26 years (from 1991 to 2017) can identify the crucial reform processes and interest group frames that have affected the CAP. We postulate that the frames of EC’s Communications on the CAP have remained the same over the years, but that most of them have undergone changes in content and priorities.

Many authors (e.g. Clock 1996; Liepins and Brandshaw 1999; Potter and Tilzey 2005; Potter 2006; Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Erjavec and Erjavec 2009; Erjavec and Erjavec 2015) have applied textual analysis in examining the argumentation of the CAP. However, to our knowledge, no researchers have carried out frame analysis, in particular a historical and comparative analysis involving all basic strategic documents, to examine the (dis)continuity of the EC’s CAP Communications. This paper attempts to fill this gap by employing frame analysis of the CAP Communications from the first radical reform of the CAP in 1991 to the last Communication at the end of 2017. The study has two goals: it tries to reveal what frames the EC has used in relation to its CAP reforms and how these frames have been modified during the analysed period to legitimise the maintenance of the CAP (and its budget).

Framing in the EU policy and its legitimization

According to the pioneer of framing theory Goffman, frames are “schemata of interpretation” that enable individuals to understand certain events and “to locate, perceive, identify and label” occurrences (1974, 21-22). Gamson and Modigliani (1989) defined a frame as “a central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning to an unfolding strip of events” (p. 143). Robert Entman argued that “frames define problems – determine what a causal agent is doing with what costs and benefits, usually measured in terms of common cultural values; diagnose causes – identify the forces creating the problem; make moral judgements – evaluate causal agents and their effects; and suggest remedies – offer and justify treatments for the problems and predict their likely effects” (Entman 1993, 52). He added that “to frame is to select some aspect of perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (1993, 52). A frame is a kind of filter through which people perceive the world and provides the structure of a message that is intended to activate a particular interpretation of the world. For political purposes, texts, such as political documents or political speeches, reinforce a certain representation of political reality and a certain emotion towards it by choosing some key words, strategic phrases, catchphrases, slogans, and images and by leaving out other elements that might suggest a different perspective or create a different sentiment (D’Angelo 2002).

As in other political decision-making processes, framing plays an important role in EU policy debates. Ringe (2005, 2010) showed how structural factors, such as ideology, shape policy preferences to the extent that the EU legislative actors successfully link them to specific policy proposals by providing strategic frames that draw attention to certain aspects of a legislative proposal and thus shape the prevailing interpretation of its content and consequences. This interpretation affects both policy preferences at individual level and policy outcomes.

When policy-makers launch a legislative initiative that affects the policy concerns of interest groups, they have an incentive to shape the outcome of the policy debate in their favour (Klüver et al. 2015). This applies to any policy, especially of the CAP, which affects many people and provides relatively large financial resources (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015). The way interest groups frame a debate has an impact on the policy options considered by decision makers and on the final outcome of a legislative debate (Mahoney and Baumgartner 2008; Baumgartner et al. 2009; Klüver et al. 2015). Since many citizen groups do not have massive lobbying budgets, framing is their only available tool. Based on a novel dataset on framing strategies of more than 3000 interest groups in 44 EU policy debates included in the policy proposals adopted by the EC, Klüver et al. (2015) shed light on the determinants of frame selection in the policy formulation phase when the EC drafts its policy proposals; they showed that frame selection systematically varies across interest group type and institutional venues. Using the contextual approach to EU legislative lobbying and analysing a set of 125 legislative proposals submitted by the EC between 2008 and 2010, Klüver, Braun and Beyers (2015, 54) demonstrated “the inherently multi-faceted nature of interest representation and that the policy and institutional context significantly affects the role interest groups play in the EU”. Eising et al. (2015) analysed not only variation across and within policy areas, but also across the EU and national levels, as well as across four member states (MS). They found that both contexts and strategies have a significant influence on the number and type of frames in EU policy debates and that the more actors become involved in the policy debates, the more frame competition intensifies.

We have not found any study in the existing literature on how frames have changed historically or on the use of framing to legitimise an established policy such as the CAP. Namely, legitimization is a principal and intrinsic goal sought by political actors, whose aim is to maintain their hegemonic power through different means, and, in particular, by emphasising certain meanings (Capone 2010; Reyes 2011). It deserves special attention in political analysis because it is from this speech that political actors justify their political agenda in order to influence the direction of policy (Reyes 2011). Therefore, this study examines changing frames as a means of legitimising the CAP.

CAP reforms (1992–2017)

The CAP was introduced in 1962 to translate the objectives defined in the Treaty of Rome (1957) into policy terms. Since then, it has undergone several reforms. In the initial period (1962–1992), it was founded on market price and production support in the form of import duties, export subsidies, and internal market support measures, using the last two to remove surplus products from the domestic market (Garzon 2006).

Production-coupled support (1992–2003)

The second period, marked by the introduction of direct support (1992–2003), was announced by the Communication “The Development and Future of the CAP” (European Commission 1991). Known as the “MacSharry reform”, it introduced the first significant policy changes towards constraining trade distortions and curbing the growth of the CAP’s budgetary costs (Tracy 1993; Moyer and Josling 2002; Garzon 2006). The reform was a result of extensive negotiations in the GATT Uruguay Round of multi-lateral trade negotiations, in which trading partners, primarily the USA, exerted extreme pressure on the EC to liberalise agri-food trade, demanding a significant decrease in tariffs and abolishment of export subsidies (Josling et al. 1996; Swinbank 1999). The proposal for significant CAP reform was presented by the Commissioner for Agriculture Ray MacSharry to the Council of Ministers, accompanied by strong criticism from conservative Member states (MS) and fierce protests by farmers’ organisations throughout Europe (Fennell, 2002). This first significant CAP reform reduced market-price support and introduced “compensatory (coupled) payments”, specifically for the production of grain, oilseeds, beef, and small ruminants, which were determined according to past production and market-price support levels (Josling et al. 1996; Grant 1997).

The next Communication “Agenda 2000: For a stronger and wider Union” (European Commission 1997) initiated the next step of the reform process, usually described as a continuation of the MacSharry reform. The main decision-making process took place in the Council of Ministers and the European Council (Garzon 2006). The conflict among MS revolved mainly around the distribution of resources and further liberalisation of the market, especially on dairy (Lynggaard and Nedergaard 2009). The reform altered intervention prices for some key products, such as grains, lowering them to world market-price levels, and widened the scope of direct support accordingly, as well as upgraded the structural measures, integrating them into the CAP Rural development policy (Buckwell and Tangermann 1999; Swinbank 1999; Moyer and Josling 2002; Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2004; Garzon 2006; Erjavec and Lovec 2017).

Historical decoupled support (2003–2020)

Historical decoupled support

The second observed period started with the “Fischler reform” in 2003, which was introduced by the Communication “Mid-Term Review of the Common Agricultural Policy” (European Commission 2002) attempting to introduce “new content” into an essentially unchanged (Erjavec and Erjavec, 2009) policy, while continuing its liberalisation (Garzon 2006; Swinnen 2008). The process of reform took place in light of expectations of further pressure on trade negotiations (WTO Doha Round), the EU’s enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe, and growing budgetary concerns of pro-reform MS (UK, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark) (Potter and Tilzey 2005; Potter 2006). Additionally, societal pressures increased to integrate new elements into agricultural policy, such as strengthening environmental aspects and providing a higher degree of food safety (due to food scandals). A key actor was Commissioner for Agriculture Franz Fischler, who introduced a relatively radical proposal that entailed decoupling direct payments and further market liberalisation while maintaining the agricultural budget (Swinnen 2008).

The reform replaced coupled support with direct payments based on historical rights and decoupled from current production. The interests of farmers’ groups, which were strongly involved in the debate at both the national and multi-national level (Garzon 2006), were taken into account by implementing historical payments (retention of the extent of payments on the farm). Apart from historical schemes, the EU (MS) could also apply regional and hybrid schemes (static or dynamic). Payments were henceforth conditional upon cross-compliance—following a number of regulations and keeping land in “good agricultural and environmental condition”. Through the mechanism of “modulation”, part of the largest individual payments was transferred to Pillar II (Erjavec and Lovec 2017). An important element of the reform was the strengthening of rural development policy as a legally and policy consistent, independent part of CAP (Pillar II) with its own system of strategic planning and set of measures.

In 2008, with the CAP “Health check” (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2011), based on the Communication “Preparing for the ‘Health Check’ of the CAP reform” (European Commission 2007), the Council of the European Union went a step further along the lines of the Fischler reform by agreeing to abandon milk quotas in 2015, continuing to decouple support, increasing the scope of modulation (including through “degressive capping”), and strengthening member states’ flexibility in policy implementation (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2011). The main actors were the same as in the previous period, although due to only minor changes in agricultural policy there were no sharp confrontations between them (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2011).

New societal concerns

After 2010, the new debate on CAP reform started, during which environmental (greening) concerns were given more attention, at least declaratively (European Commission 2010). Since there was no radical change in the agricultural policy, it is considered to be more a continuation of the change initiated in 2002 than a genuine reform (Swinnen 2018). The period began with the Communication “The CAP towards 2020: Meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future” (European Commission 2010), followed by the 2013 agreement on the “Greening” of the CAP, which, apart from further liberalising some elements of the policy, attempted to re-orient it towards new, mostly environmental objectives. The decision-making process was characterised by an increased number of involved interest groups (new networks of environmental NGOs) and changes in the adoption process—the Lisbon Treaty had given the European parliament (EP) the status of full co-legislator in the co-decision procedure (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015).

Before the formal legislative process, a wide public debate was launched. In addition to many farmer interest groups, it also included a number of environmental groups. Their expectations regarding the outcome of the negotiations were not fulfilled, as the final round of negotiation in the Council and the EP rather weakened the concept of reform (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015). In the field of market measures, the reform removed sugar quotas and strengthened the safety net logic in the management of markets and crises (Swinnen 2018). It shifted existing Pillar I direct support towards per-area payments, with increasing convergence both between and within MS. A “green component” was introduced into the direct payment schemes, accounting for 30% of the payment and conditional upon certain environmental actions. MS were able to implement simplified schemes and flexible options, which included switching part of the funds between Pillars I and II, granting more flexibility to MS with below-average payment levels.

At the time of writing of this paper, EU institutions and interest groups are at the end of negotiations on a new CAP reform to determine the policy after 2021, introduced by the EC Communication “The Future of Food and Farming” (European Commission 2017a). The key proposals maintain the basic principles of the CAP while strengthening the societal concerns introduced by a previous strategy highlighting the environment, but also introducing new topic like food health issue. There is again a special focus on the environment, including the proposal to incorporate more result-oriented measures. The fundamental change proposed by the EC is the introduction of CAP Strategic plans, in which MS will have to justify and define the specific needs, objectives, and measures of their respective agricultural policies on the basis of strategic guidelines provided by the common legislative framework (Mathews, 2018). The Communication thus proposes to devolve more decision-making power to the MS level, presumably yielding a CAP that is better suited to local conditions.

The new agricultural policy is shaped by the same actors as in the adoption of policies for the period 2014–2020. Due to increased support in the public debate, the influence of the environmental organisations, which are drawing attention to accountability-related deficiencies of the proposal, has increased (Erjavec et al. 2018). Even more than in the previous reform processes, the role of the European parliament is strengthening. In addition to the Committee for agriculture, the Committee for the environment has been given formal competences regarding the CAP, reflecting the rising societal concerns for agricultural policy (Erjavec et al. 2018).

The five frames of CAP reform

Five frames might be identified from the highlights of the CAP reforms (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Henning, 2009; Cunha and Swinbank 2011; Swinnen 2018). In all reforms, the foreign trade frame, which was pushed by multi-national trade negotiations (GATT/WTO) and especially the USA in the 1990s, might be identified. Farmer groups influenced the CAP reforms by lobbying at the national and multi-national levels, using farmers’ economic interest frames. The European Council was primarily focused on the distribution of financial resources according to MS priorities and constructed a budgetary frame. The environmental NGO network was focused on the societal concerns frame, especially on the environment, food safety, and quality. The policy mechanisms frame was highlighted by the Commission through its right to propose legal changes. This frame is primarily designed in the EU decision-making process that includes the Council of European Union (agricultural ministers) and also the European parliament after 2010. The question arises how these frames were reflected in the EC’s Communications throughout the history of CAP reforms and how the EC used them to legitimise the CAP.

Methodology

Method

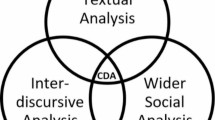

This study based on a qualitative content analysis of the frames used in the EC’s Communications over the past 26 years (from 1991 to 2017). The identification of frames requires that the researcher knows “how” to search for frames and “what” to look for when identifying frames. The “how” of frame identification is based on the ongoing comparative technique of Wimmer and Dominick (2006, 117-118): comparative assignment of incidents to frames, elaboration and refinement of frames, search for relationships and topics between frames, and simplification and integration of data into a coherent theoretical structure. The “what” of identifying frames implies that the researcher examines the text for “symbolic devices” or “framing devices” that are located within texts. The framing devices are manifest elements in a document that act as verifiable indicators of the frame. Most commonly, keywords, catchwords, argumentative structures, and strategic phrases are used to summarise the message on the main topic and visual images. There are also other framing devices, such as metaphors, information sources, page placement, figures, and photos (Pan and Kosicki, 1993; Van Gorp and van der Goot 2012).

Sample

In order to gain comprehensive insight into the changes of frames, all six of the EC’s communications from 1991 to 2017 (Table 1) were included in the study (European Commission, 1991, 1997, 2002, 2007, 2010, 2017a) and four subject areas were analysed: drivers of changes, objectives with priorities, proposed measures and mechanisms, and the CAP budget (Hill 2018).

Coding and analysis

In the analysis, we followed the process of inductive analysis—where frames emerge as the research progresses—primarily developed by Van Gorp (2010; 2012) and upgraded by Touri and Koteyko (2015). Van Gorp’s method, which uses the frame matrix, is one of the most systematic qualitative approaches to frame analysis (Touri and Koteyko 2015, 606).

In a first step, the Communications were generally read several times and descriptive notes were made about the content. Then, a second reading was performed to code the data, i.e. to highlight phrases or sentences and to add shorthand or codes to describe their content. Then, we identified patterns among the codes, combined similar codes into an abstract single theme. We reviewed the themes by returning to the documents and checking whether the themes represented the content of Communications. We named the themes with a concise and easily understandable name. The documents analysed consisted of five main coherent themes (policy mechanism, farmers’ economics, foreign trade, societal concerns, budgetary). Then, we identified concepts describing the themes based on the ongoing comparison technique described above. The identified concepts or main ideas had identifiable conceptual characteristics and could be reliably distinguished from the concept of other frames. In the next steps, we analysed the documents for “symbolic devices” or manifested framing devices that could contribute to the public’s interpretation of the Communications. We used the usual framework devices, i.e. keywords and strategic phrases. We identified similarities, differences, and contrasts between the keywords and connect them to concepts. We created frame packages by identifying a logical chain of keywords that convey a coherent main idea or concept. We integrated keywords, concepts and examples into the frame matrix construction.

In addition, we advanced a step from current framing analysis by conducting a comparative historical analysis of the identified frames. We looked for similarities, differences, and contrasts between the frames between the individual EC’s Communications and identified their coherence and discrepancy. The next step was to examine the structure of the specific Communications to determine the predominance of a particular frame and how they intertwine: it dominates in the document—“very important” frame, it covers a large part of the text—“important” frame, and it covers a small part of the document—“less important” frame. In the end, we have formed the frame matrix in three historical periods, which also show how the importance of frames with corresponding keywords has changed. Both authors conducted coding independently, with regular discussion of the coding process to limit possible inconsistencies.

Results

Five frames were distinguished in the Communications and thus constitute the answer to the first research question. Alternative frames are conceivable, but these five presented themselves most prominently during the analysis. Below is a presentation of the results of our comparative historical analysis of the frames, which answers the second question of how the frames were modified in the analysed period in order to legitimise the preservation of the CAP. This was determined by taking into account the focus and special preference of the frames in the respective Communications. Three tables describing the five frames were constructed, demonstrating their development in each subsequent period: “Production-coupled support” (1992–2003), “Historical decoupled support” (2004–2013), and “New societal objectives” (2013–).

Policy mechanism frame

The first frame is constructed around the concept of implementation of the CAP’s reform objectives and was initially primarily focused on elaborating and describing policy measures. A historical comparative analysis of the frames shows that measures were clearly and broadly incorporated in all the analysed Communications except in the last one (European Communication 2017a), where they are only implied. In most of the analysed documents, this was one of the dominant frames in terms of priority and scope, since it comprises a considerable part (about a quarter) of the documents. While in the first observed periods, measures were specified in the Communications and pertained to specific sectors (e.g. cereals, livestock, milk), latter documents focussed more on objectives (European Commission 2010).

This frame was formed by neologistic jargon, composed of technical keywords that are difficult to understand for laymen, such as “single farm payments”, “voluntary coupled support”, “cross compliance”, and “dairy quotas”, implying professionalism and thus the sensibility of implementing the proposed measures (Table 2). This primarily pertains to the “first pillar” of the CAP (market-price policy), where measures were mostly not precisely defined, but merely included as a result of path dependency and subject to political bargaining between decision makers.

In the last Communication (European Commission 2017a), there is also no detailed proposal of policy measures like in the previous strategic documents. The Communication from 2017 has also constructed this frame with implementation in mind, although in a completely different way: by proposing a new “delivery model of the CAP”, in which the EU would only set the basic policy parameters, leaving the details of implementation to MS. This would give MS more autonomy, but they would bear greater responsibility and be more accountable as to how they meet the objectives and achieve agreed-upon targets. Instead of the EC, MS were defined as the main actors to determine the content and implementation of the policy through their own strategic plans. The document did not define a framework for the strategic planning, nor a role of EC’s control system. Thus, the policy mechanism has been reframed in the last Communication in terms of the implementation of reform and in terms of its placement: it is no longer central to the document. The main keywords, such as “implementation of policy” and “policy instruments”, have also been included in the last Communication, but the frame is no longer constructed using narrowly professional words. Instead, a new and more strategic vocabulary is included, using words such as “strategic plan” and “a new delivery model” (Table 3).

Farmers’ economic frame

The second frame is the most typical of CAP reform, consistently included in all the analysed Communications. It is based on farmers’ interests: of providing farmers with a sufficient and stable income, ensuring quality of life on small farms, generation renewal, reducing structural inequalities in agricultural development among members, and maintaining a social balance. By emphasising farmers’ incomes and their distribution, the frame reflects a conservative segment of the CAP reforms. The pressure to maintain the income support nature of the CAP has been constant throughout the studied period and has resulted from the influence of farmers’ professional associations at the national and multi-national levels and the EU agricultural ministers (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Henning 2009; Cunha and Swinbank 2011; Swinnen 2018).

Comparative historical analysis of this frame also shows that a new focus, namely the farmer’s position in the value chain, has appeared in the last Communication. The analysis of keywords shows that in all Communications, phrases such as “stability of farm incomes”, “ageing of farmers”, “social balance”, and “fair standard of living”, constructed this frame. Additionally, in the last Communication, the frame was also constructed by the new phrase “resilient agriculture”. These are again farmers’ interests in a new guise: farmers should be supported in order to be risk-tolerant. Although the keyword “risk” also appeared in previous Communications, it has gained in importance in the last document by being assigned to “management” and by referring to the use of more modern approaches to risk reduction, such as “the use of indexes to calculate farm income losses, reducing red tape and costs”, exchange of views between farmers, authorities, and stakeholders to share experience and best practices in “risk management” and “the development of an integrated and coherent approach to risk prevention, management and resilience”. Hence, this frame’s construction has remained roughly equal, and it has remained in the same preferential position—neither the most nor the least important—in all Communications; in the last one, the keywords were only modernised to better legitimise retaining the CAP.

Foreign trade frame

The third frame is used to highlight market and trade orientation, as well as efficiency and global and domestic competitiveness. It features prominently in most of the analysed documents, but is no longer crucial in the 2017 Communication. Trade issues and a growing market orientation were treated as an important subject in the first Communications (1991, 1997, and 2002) as a result of the then-ongoing multi-lateral trade negotiations, yet later significantly decreased in importance (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Henning 2009; Cunha and Swinbank 2011; Swinnen 2018).

In the last Communication, this frame, which was based on the elements of liberal ideology, is constructed with the justifications that “Maintaining the market-orientation of the EU agri-food sector and the compatibility of CAP measures with international trade law will also allow the EU to retain its leading role in international bodies such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), …” and “Foster a smart agriculture to strengthen overall competitiveness of the agricultural sector”. While the Communications in the 1990s and the last one included only a few keywords belonging to this frame, the frame constructed in the Communications from 2002 to 2007 consisted of many keywords, such as “market orientation”, “competitiveness”, “reduction of price supports”, and “domestic prices close to world market” (Table 4). Thus, this frame, which was preferred in most of the analysed Communications, has remained in the last Communication, but its relevance has become much smaller.

Policy budgetary frame

The fourth frame in the studied material is constructed around the CAP budget and contains the scope of the budget, distribution between MS, the share of budget allocated to each pillar, and justification of the CAP. Comparative historical analysis of this frame has shown that the budget was highlighted in different ways—both as elaboration of expenditure and as a justification of the CAP.

Firstly, the Communications from 1997 and 2002 included an elaboration of the budget for the CAP with detailed financial expenditure, including typical budgetary keywords such as “budget”, “expenditure”, “ceilings”, “pillars”, “budgetary stabilization”, “financial framework”, and “budgetary balance”, indicating the proposal for the distribution of financial resources. Conversely, the Communications from 2017, 2010, and 1991 did not include a financial framework at all; in these years, the budgetary strategy was provided separately within the proposals for the multi-annual financial frameworks.

Secondly, most of the Communications also included justification of the budget as an objective, which is most evidently formulated in the 2002 Communication, where the EC explicitly stated “justification of support through the provision of services that the public expects farmers to provide” (European Commission 2002) as an objective, using key phrases such as “justification of support” and “justification of the CAP”. In the last Communication, the legitimization of the financial distribution of the CAP was presented in the introduction to the Communication, where the justification of the CAP budget referred to consumer concerns in relation to the CAP. The EC stated that agriculture should provide “a wide variety of food that carries broader benefits for society” and places a “stronger focus on the provision of public goods”. Surprisingly, the word budget was not explicitly mentioned in the context of the CAP, only in connection with the EU budget. Thus, in the Communications from 2002 and 1997, the CAP budget was presented in detail, while in the last Communication it was excluded from the documents and only implicitly incorporated as a justification for the distribution of the EU agricultural budget. Thus, this frame, which was in the focus in the initial Communications both as an elaboration of expenditure and justification of the CAP as an objective, was reframed as the justification of budgetary expenditure by emphasising the benefit for society in the 2017 Communication.

Societal concerns frame

Societal issues provide the last frame for communicating about CAP reforms. Predominantly, it is constructed from environmental protection, food safety and quality, and animal welfare and public health in the last period. Comparative historical analysis of this frame shows that the environmental objective has been included in all analysed Communications; however, its positioning in the documents and naming have been changed. In the first Communication, it was barely included, but later it became a dominant objective in terms of priority and scope, and this has intensified in the latest Communication (European Commission 2017a). The key difference appears to be in the keywords used. In the 1991 Communication, it was phrased as “to preserve the natural environment”, and in the 2002 Communication as “to support environmentally friendly products” and “cross-compliance to support the implementation of environmental, food safety, and animal health and welfare legislation”. In the 2010 Communication, the new phrase “environmental public goods” was included in the objective “to guarantee sustainable production practices and secure the enhanced provision of environmental public goods”. In the last Communication, it was phrased “to promote environmental care and climate action and to contribute to the environmental and climate goals of the EU”. The EC has been changing the keywords of environmental elements in line with societal changes and concerns to address a wider audience.

In the Communications published at the beginning of the century, it is food quality and safety that have become a key element of the societal concerns frame, and “food quality”, “high quality and wide choice of food products”, “food security”, “quality products”, and “local products” are the main keywords. Although the recent Communication also used keywords such as “food quality” and “food safety”, it understands them in a new or additional sense as a public health issue. Food quality and safety addressed the reduced use of pesticides and antibiotics in their production. For example, “The CAP should become more apt at addressing critical health issues, such as those related to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) caused by inappropriate use of antibiotics.” In addition, food quality and its availability were also linked to other important social health issues, such as obesity: promoting “healthier nutrition, helping to reduce the problem of obesity and malnutrition, making nutritious, valuable products such as fruits and vegetables easily available for EU citizens”. The concept “One Health”, which focuses equally on human and animal health, has been introduced as an additional health dimension. The last two Communications, especially the last one, also included innovation and digitalisation as prominent elements of this frame. These two keywords were also linked to other keywords, e.g. risk management, which gave the whole Communication a sense of timeliness and connection to the social process. Moreover, the last one also represents a turning point, as it includes a completely new, yet highly socially resonant element, i.e. migration, though not in the foreground. In the last Communication, this frame was focused on a combination of general societal issues, such as the environment, climate change, food quality, health, digitalisation, and migration, with those issues recurring throughout most of the Communisations gaining new or at least additional meaning. It was the dominant frame in terms of the priority and space it was given. Thus, by changing the main priorities of the frame and introducing new highlights, a new justification for the CAP was created by the EC.

Discussion and conclusion

The Communications on the CAP’s reforms are complex. In each reform, there have been various powerful interest groups that have influenced the debate and production of these strategic documents by the EC. The comparative historical framing analysis of EC's Communications on the reform of CAP from 1991 to 2017 identified the use of five frames that have remained essentially the same and can be recognised as long-term reform drivers of the CAP; however, most of them (budget, societal concerns, market, and trade) have been changed in content and priorities through the time. On the other hand, the policy mechanisms frame, which was a kind of result of the other four frames—since it determines how to implement the CAP objectives—has been changed significantly over the years.

A stable frame of the CAP in terms of priority and importance is the farmers’ economic frame, which is focused on farmers’ incomes. It is the essence of the CAP, which is slowing down reforms and introducing path dependency into agricultural policy (Kay 2011). This indicates the power of farm lobbies, which have historically strongly influenced the conservative MS and members of the EP. Many MS are strongly motivated to maintain the existing distribution of EU budgetary resources (Heinemann et al. 2010) and the rigidity of the CAP reform process is, therefore, a characteristic that plays in their favour.

The policy mechanism frame has been modified. In the initial Communications, the EC proposed extensive and precisely defined measures, especially for the “first pillar” of the CAP (market-price policy); the implementation of various forms of direct support as the dominant form of support followed. The frame has lost a part of its priority and has been reframed as a new mode of strategic planning, in which MS are responsible for the content and implementation of the agricultural policy. This might be a result of the complexity of societal concerns and probably also of the weakness of the EU institutions, especially the tensions between MS and EC, which is no longer politically able to define new reform orientations in detail, but only as a guide (Bickerton et al. 2014). Additionally, it might be a sign of a beginning of the CAP’s marginalisation. Other policy fields, such as security, public health, digitalisation, and the fiscal and monetary union, are gaining in importance (European Commission, 2018), and the power of agricultural actors may be weakened, especially considering the political changes in France, which has historically always supported the preservation of a strong and protectionist CAP (Roederer-Rynning 2002).

The foreign trade frame has continually been included in all analysed Communications, but its importance has decreased. This might be explained by the fact that after the CAP underwent liberalisation and the reduction of market-price support in its early reforms (Swinnen 2018), the pressure of multi-lateral trade negotiations halted and this fundamental driver lost its importance.

Our comparative historical framing analysis also shows that the societal concerns frame has changed and strengthening significantly. While the environment was barely present in the early Communications, it has become much more important in the recent Communications, in addition to other general societal issues, such as climate change, food quality, health, and even migration. This shows the increasingly important role of “cause groups” who fight for a public good (Klüver et al. 2015), such as the environmental and consumer NGOs and public in general (Enly and Skogerbø 2013), in setting the agenda of CAP (Medina and Potter 2017). It might also be explained by the increase in the power of MS in relation to the EU authorities, or so-called new intergovernmentalism (Bickerton et al. 2014). As EU integration took place in the absence of supranationalism, new institutions were created that have concentrated the powers and activities of national governments and national representatives. This process is manifested by the proposed new CAP implementation model in the latest EC’s Communication, which transfers a great responsibility for the formation and implementation of the CAP to MS.

How has the process of legitimising the CAP and its budget manifested itself in the analysed Communications? It is primarily reflected above all in the paradigmatic change in the last Communication, more precisely in the marginalisation of the policy mechanism frame and its reframing with the new implementation model, as well as in the increasing importance of the societal concerns frame with social justifications of the CAP. The upgrading of the environmental element within the societal concerns frame during the reforms can also be understood as a “hidden” struggle for the budget. The need for legitimization is primarily based on the expected reduction of the financial resources allocated to the CAP. The future budget of the European Union is under the pressure from a net contributor exit (UK) from the EU, as well as of new issues (related to security and governance of the single currency) and policies that will continue to weight on the EU budget (Begg 2017).

This study contributes to the relevant literature by presenting findings on the frames constructed by the EC in relation to the key influences over the years in all basic strategic documents and revealing a (dis)continuity of the EC’s Communications on the CAP. The study revealed relatively stable frames that are constantly, but very slowly changing, as they are the result of a complex political process and the power of interest groups, especially farmers’ groups. Nevertheless, the policy changes are also visible in the long term when examined from the historical perspective of EC’s Communications. However, it is a fact that the EU continues to pursue the CAP as a financially and politically strong EU policy, as shown by the results of the negotiations on the EU’s multi-annual financial framework in the European context, which were concluded in July 2020 (European Council, 2020a). Like all empirical studies, this study has some limitations. The main limitation is that it focuses only on the EC’s Communications. Future studies might integrate documents and statements of the main interest groups to determine their influence on the EC’s policy and the interactions between them.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used for the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

Common Agricultural Policy

- EC:

-

European Commission

- MS:

-

Member state

References

Baumgartner FR, Berry JM, Hojnacki M, Kimball DC, Leech BL (2009) Lobbying and policy change: who wins, who loses, and why. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Baumgartner FR, Mahoney C (2008) The two faces of framing – individual level framing and collective issue definition in the European Union. European Union Politics 9(3):435–449

Begg I (2017) The EU budget after 2020. SIEPS 9(1):1–9

Bickerton C, Hodson D, Puetter U (eds) (2014) The new intergovernmentalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Buckwell A, Tangermann S (1999) The CAP and Central and Eastern Europe. In: Ritson C, Harvey D R (eds) The Common Agricultural Policy. Oxford: CAB International; pp. 307–342

Capone A (2010) Barack Obama’s South Carolina speech. Journal of Pragmatics 42:2964–2977

Clock P (1996) Looking through European eyes? Sociologia Ruralis 36(4):305–330

Cunha A, Swinbank A (2011) An inside view of the CAP reform process. University Press Oxford, Oxford

D’Angelo P (2002) News framing as a multiparadigmatic research program: a response to Entman. Journal of Communication 52(4):870–888

Daugbjerg C, Swinbank A (2007) The politics of CAP reform. Journal of Common Market Studies 45(1):1–22

Daugbjerg C, Swinbank A (2011) Explaining the ‘Health Check’ of the common agricultural policy. Policy Studies 32(2):127–141

Daugbjerg C, Swinbank A (2004) The CAP and EU Enlargement: Prospects for an Alternative Strategy to Avoid the Lock-in of CAP Support. JCMS Journal of Common Market Studies 42(1):99–119

Daviter F (2009) Schattschneider in Brussels: how policy conflict reshaped the biotechnology agenda in the European Union. West European Politics 32(6):1118–1139

Daviter F (2011) Policy Framing in the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Eising R, Rasch D, Rozbicka P (2015) Institutions, policies, and arguments: context and strategy in EU policy framing. Journal of European Public Policy 22(4):516–533

Enly GS, Skogerbø E (2013) Personalized campaigns in party-centered politics. Information, Communication & Society 16(5):757–774

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Communication 43(1):51–58

Erjavec E, Lovec M (2017) Research of European Union's Common Agricultural Policy. European Review of Agricultural Economics 44(3):732–754

Erjavec E, Lovec M, Juvančič L, Šumrada T, Rac I (2018) Research forAGRICommittee–The CAP Strategic Plans beyond 2020. Brussels. Available via http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2018)617501. Accessed 31 Mar 2019

Erjavec K, Erjavec E (2009) Changing EU agricultural policy discourses? The discourse analysis of Commissioner's speeches 2000-2007. Food Policy 34(1):218–226

Erjavec K, Erjavec E (2015) Greening the CAP - just a fashionable justification? Food Policy 51(1):53–62

European Commission (1991) The development and future of the CAP. Brussels, 1 February 1991. Available via https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/cap-history/1992-reform/com91-100_en.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Commission (1997) Agenda 2000: For a stronger and wider Union. Brussels, 15 July 1997. Available via: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/cap-history/agenda-2000/com97-2000_en.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 1997

European Commission (2002) Mid-Term Review of the Common Agricultural Policy. 10 July 2002. Available via http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52002DC0394. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Commission (2007) Preparing for the ‘Health Check’ of the CAP reform. 20 November 2007. Available via http://edepot.wur.nl/117130. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Commission (2010) The CAP towards 2020: meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future presented. 18 November 2010 Available via: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/cap-post-2013/communication/com2010-672_en.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Commission (2017a) The future of food and farming. Brussels, 29 November 2017. Available via https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/future-of-cap/future_of_food_and_farming_communication_en.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Commission (2018) 2018 EU budget: job, investment, migration challenge and security. Available via http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-4687_en.htm. Accessed 3 Dec. 2017

European Council (2020a) Available via https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/european-council/2020/07/17-21 Accessed 24 Aug 2020

Fennell R (2002) The Common Agricultural Policy: continuity and change. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gamson W A, Modigliani A (1989) Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95(1):1–37

Garzon I (2006) Reforming the CAP. History of a Paradigm Change. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK

Grant Wyn P (1997) The Common Agricultural Policy. Basingstoke: Macmillan

Heinemann F, Mohl P, Osterloh S (2010) Reforming the EU Budget. Journal of European Integration 32(1):59–76

Henning HCA (2009) Networks of power in the CAP system of the EU-15 and EU-27. J Public Pol 29(2):153–177

Hill B (2018) Farm incomes, wealth and agricultural policy. Routledge, New York

Josling TE, Tangermann S, Warley TK (1996) Agriculture in the GATT. Macmillan, London

Kay A (2011) Path dependency and the CAP. J Eur Public Pol 10(3):405–420

Klüver H, Braun C, Beyers J (2015) Legislative lobbying in context: towards a conceptual framework of interest group lobbying in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 22(4):447–461

Klüver H, MahoneyC OM (2015) Framing in context: how interest groups employ framing to lobby the European Commission. J Eur Public Pol 22(4):481–498

Liepins R, Brandshaw J (1999) Neo-liberal agricultural discourse in New Zeeland. Sociologia Ruralis 39(4):463–582

Lynggaard K, Nedergaard P (2009) The logic of policy development: lessons learned from reform and routine within the CAP 1980–2003. Journal of European Integration 31(3):291–309

Mahoney C, Baumgartner FR (2008) The two faces of framing: individual-level framing and collective issue definition in the European Union. Eur Union Politics 9(3):435–449

Mathews A (2018) Evaluating the legislative basis for the new CAP Strategic Plans. Available via http://capreform.eu/evaluating-the-legislative-basis-for-the-new-cap-strategic-plans/. Accessed 31 Mar 2019

Medina G, Potter C (2017) The nature and developments of the Common Agricultural Policy. J Eur Integration 39(4):373–388

Moyer W, Josling T (2002) Agricultural Policy Reform Politics and Process in the EU and US in the 1990s. Ashgate: Aldershot

Pan ZP, Kosicki GM (1993) Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Political Communication 10(1):55–75

Potter C (2006) Competing narratives for the future of European agriculture. The Geographical Journal 172(3):190–196

Potter C, Tilzey M (2005) Agricultural policy discourses in the European post-Fordist transition. Progress in Human Geography 29(5):581–600

Reyes A (2011) Strategies of legitimization in political discourse. Discourse Soc 22(6):781–807

Ringe N (2005) Policy preference formation in legislative politics: structures, actors and focal points. American Journal of Political Science 49(4):731–745

Ringe N (2010) Who decides, and how? Preferences, uncertainty, and policy choice in the European Parliament. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Roederer-Rynning, C. (2002) Farm Conflict in France and the Europeanisation of Agricultural Policy. West European Politics 25(3):105–124

Swinbank A (1999) EU agriculture, Agenda 2000 and the WTO commitments. World Economy 22(1):41–54

Swinnen JFM (2008) The perfect storm: the political economy of the Fischler Reforms of common agricultural policy. Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels

Swinnen JFM (2018) The political economy of agriculture and food policy. Palgrave McMillan, Basingstoke

Touri M, Koteyko N (2015) Using corpus linguistic software in the extraction of news frames: towards a dynamic process of frame analysis in journalistic texts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18(6):601–616

Tracy M (1993) Agricultural Policy in the European Union and Other Market Economies. La Hutte: Agricultural Policy Studies

Van Gorp B (2010) Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis. In: D’Angelo P, Kuypers J (eds) Doing news framing analysis: empirical and theoretical perspectives. Routledge, New York, pp 84–89

Van Gorp B, van der Goot M (2012) Sustainable food and agriculture: stakeholder’s frames. Communication, Culture & Critique 5(2):127–148

Wimmer RD, Dominick JR (2006) Mass media research. An introduction. (8thedition). Thomson Wadsworth, Canada

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors ‘contributions

KE conceived of the study, participated in the designing of the data collection instruments, collected the data, and performed the analysis. EE performed the analysis and provided comments on the draft manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Erjavec, K., Erjavec, E. Framing agricultural policy through the EC’s strategies on CAP reforms (1992–2017). Agric Econ 9, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-021-00178-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-021-00178-4