Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical outcome of tibial pilon fractures treated with arthroscopy and assisted reduction with an external fixator.

Methods

Thirteen patients with tibial pilon fractures underwent assisted reduction for limited lower internal fixation with an external fixator under arthroscopic guidance. The weight-bearing time was decided on the basis of repeat radiography of the tibia 3 months after surgery. Postoperative ankle function was evaluated according to the Mazur scoring system.

Results

Healing of fractures was achieved in all cases, with no complications such as severe infection, skin necrosis, or an exposed plate. There were 9 excellent, 2 good, and 2 poor outcomes, scored according to the Mazur system. The acceptance rate was 85%.

Conclusion

Arthroscopy and external fixator-assisted reduction for the minimally invasive treatment of tibial pilon fractures not only produced less trauma but also protected the soft tissues and blood supply surrounding the fractures. External fixation could indirectly provide reduction and effective operative space for arthroscopic implantation, especially for AO type B fractures and partial AO type C1 fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tibial pilon fractures affect weight-loading on the articular surface and metaphysis; these severe injuries comprise about 5–10% of all lower limb fractures, and have high complication rates (range 11.4–54%) (McFerran et al. 1992). The characteristics of pilon fractures include a variable degree of metaphyseal compression, comminution, unstable fracture height, and primary injury of the articular cartilage; pilon fractures are caused by high-energy injuries and sometimes occur in combination with a severe soft tissue injury (Watson et al. 2000; Huebner et al. 2014; Schweigkofler et al. 2015; Klaue and Cronier 2015, Krettek and Bachmann 2015a, b). Pilon fractures are usually the result of combined compressive and shear forces, and may result in instability of the metaphysis. The complexity of the injury, lack of muscle cover, and poor vascularity make these fractures difficult to treat. The risk of complications was reported to be as high as 37–54% with open reduction techniques (Teeny and Wiss 1993). Surgical treatment of pilon fractures includes several options: intramedullary nailing, external fixation, and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO). The management of tibial pilon fractures with MIPO enables the preservation of soft tissue and the remaining blood supply.

The surgical fixation method is determined according to the extent of the fracture and displaced articular surface, as well as the condition of the soft tissue. For the treatment of pilon fractures, Watson emphasized that minimally invasive separation of soft tissue not only protects the blood supply of the fractured bone but also provides indirect reduction. Watson suggested choosing the surgical approach on the basis of the condition of the injured soft tissue, and recommended the use of limited exposure and stabilization with small wire circular external fixators.

Thirteen patients with tibial pilon fractures underwent definitive treatment with limited open reduction and internal fixation with external fixators under arthroscopic guidance at our hospital from November 2010 to December 2013. All 13 patients reported satisfaction with the clinical outcome.

Methods

General data

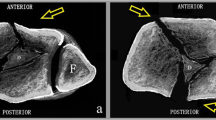

Thirteen patients were enrolled in this study, including 9 males and 4 females. Six patients experienced a fall from a high place, and 7 were injured in a traffic accident. Patient age ranged from 19 to 54 years. All had closed injuries (AO type B2 or C1); Fig. 1 lists the classic cases. The mean time from injury to surgery was about 10 days.

Preoperative preparation

Physical examination was conducted in detail before surgery to determine overall status. Fractures of the femoral neck and spinal cord and closed injuries of the chest, abdomen, and brain were excluded. The ankle joint and surrounding soft tissue were evaluated for vascular status (especially the dorsalis pedis pulse) and neurologic injury. Radiological examination of the ankle and tibiofibular joints was performed routinely. The unaffected contralateral areas were also photographed as controls. Computed tomography with three-dimensional evaluation of the ankle joint was performed to determine the position of the fracture, the position and number of cortical bones, the degree of comminution, and the extent of fracture compression and displacement. Longitudinal traction was performed to restore the ankle axes as soon as possible, followed by ankle joint fixation with a plaster slab; tuberis calcanei traction was performed on patients with severe soft tissue injury. Intravenous mannitol and dexamethasone were used before surgery to alleviate local soft tissue edema and inflammation. Blisters were aspirated with a sterile syringe. Surgery was performed 7–14 days after the injury when soft tissue had healed or swelling had dissipated.

Operative treatment

Surgical treatment was successfully used for open fractures, compartment syndrome, step-off height from the joint surface >2 mm, and tibial pilon fractures in which the angle of any plane surface was >10°. The aim of surgery was to restore the function of the bone and soft tissues, perform anatomical reduction of the joint surface, and provide stability of the fracture to allow return to functional exercise as early as possible. In selecting treatment, the extent of soft tissue injury should be considered. For a classic AO type C1 pilon fracture, we selected a minimally invasive treatment (Fig. 1). The fibula was plated and the tibial side was stabilized with a locking plate and screws. Surgical treatment was performed in multiple steps, including restoration of lower limb length, restoration of the metaphyseal outline, bone grafting, and metaphyseal reduction and fixation.

The first step restored the length of the fibula. Posterolateral incision over the fibula was performed to expose the broken end under direct vision, followed by anatomical plate fixation after reduction. The second step involved placement of external fixators for the reduction of the distal tibia. Two screws traversed the tibia and one screw traversed the tuberis calcanei; the two sides of the distal tibia were slowly unfolded. Indirect reduction with external fixators was then performed, with an increase in soft tissue tension and recovery of limb length and alignment. The unfolding tibial reduction expanded the space in the ankle joint available for implantation and arthroscopic surgery, and allowed direct observation of the status of the reduction. The third step involved percutaneous reduction by leverage under arthroscopic guidance; this achieved planarization of the joint surface as confirmed with imaging during surgery (Fig. 2). First, two small incisions were made at the front of the ankle; then, the arthroscopic camera and instruments (Stryker Corporation, USA) were smoothly inserted into the ankle through these portals for observation and reduction of the fracture (Figs. 3, 4). The anterolateral approach was located at the outside articular line of the extensor digitorum pedis longus tendon. The anteromedial approach was located at the inside articular line of the anterior tibial tendon. Blood clots and bone scraps were cleared under arthroscopy, and the condition of fracture displacement was observed. Common fractures were directly treated with percutaneous reduction by leverage. Articular surfaces were restored to smoothness through picking with a hook. For comminuted metaphyseal fractures, a 3–4-cm longitudinal incision was made over the tibia near the joint surface; blunt dissection was then performed to reach the fracture point, and the broken bone in front of the metaphyseal fracture was exposed. A fascia stripper was used to perform percutaneous reduction by leverage of the exposed fracture pieces under arthroscopy. When the step-off height of the joint surface was <2 mm, a 1.5-mm Kirschner wire was used to temporarily fix the fracture. The fourth step involved bone grafting of the tibial metaphysis. Autogenic ilium packing traction and reduction were performed through the anterior tibial incision. The remaining bone defect in the metaphysis was subjected to adequate bone grafting. The fifth step involved tibial internal or anterior plate fixation. The use of anterior or internal anatomical plates depended on the type of fracture. A minimally invasive plate was placed between the fascia and periosteum, and 3–4 screws were used to fix the two ends of the fractures. Lag screws were needed for patients with an accompanying fracture of the posterior malleolus.

For postoperative management, antibiotics were used for 3 days to prevent infection, and the affected limb was elevated. If tolerated, the patients performed bed exercises. To determine weight-bearing time, radiography of the ankle joint was repeated at 3 months after surgery.

Results

Sutures were removed at 2 weeks after surgery in all patients. There were no complications such as severe infection, skin necrosis, or an exposed plate (Table 1; Fig. 5). The postoperative radiographs showed good fracture reduction and position of the internal fixators (Fig. 6). All patients were followed. Radiographic examination was performed at 3 and 6 months after surgery. The longest follow-up time was 1 year. After 6 months, the radiographic results showed good fracture union without malunion, and good callus growth in the grafted region. The fracture healing time ranged from 8 to 16 weeks (mean, 12 weeks), and no disunion occurred. The efficacy of surgery was evaluated by using the Mazur grading system, with 9 cases scored as excellent, 2 as good, and 2 as poor (Mazur et al. 1979). The satisfaction rate was 85%. The 2 patients with poor outcomes developed slight traumatic arthritis and experienced slight pain during walking.

Discussion

The surgical treatment of tibial pilon fractures includes open reduction and internal fixation, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation, minimally invasive treatment, and fusion of the ankle joint. According to the type of fracture and extent of soft tissue and open injury, early or delayed open reduction and internal fixation are chosen to reduce the occurrence of complications. Ankle arthroscopy may be used, along with open techniques of fracture repair. This can help to ensure normal alignment of bone and cartilage, and may also be used during fracture repair to look for cartilage injuries inside the ankle.

Sirkin et al. (2004) used open reduction and internal fixation to treat high-energy tibial fractures in a two-stage protocol according to the characteristics of the soft tissue injury. This protocol consisted of immediate open reduction and internal fixation of the fibular fracture at the early stage of injury, with simultaneous fixation of the tibial fracture using external fixators to span the ankle joint; then, anatomical reduction of the distal tibial articular surface and internal fixation were conducted after the repair of local soft tissue, to reduce the incidence of wound complications. Pollak et al. (2003) considered limited internal fixation combined with the use of external fixators to be optimal for treatment of patients with severe skeletal and soft tissue injuries; however, no advantage was shown over other methods in the treatment of patients without soft tissue injury. Japjec et al. (2013) treated 15 patients with pilon fractures (AO types C2 and C3) with fixation using external fixators and limited open reduction and internal fixation, and concluded that compared with formal open reduction and plate internal fixation, this method resulted in fewer wound complications and better ankle function.

Minimally invasive methods have been used to treat fractures according to the principles of biological osteosynthesis. Minimally invasive technology uses indirect reduction to reduce unnecessary exposure, and focuses on the management of surrounding soft tissue to protect the broken end of the fractures and surrounding blood supply, and thus improve the capacity for bony healing. Minimally invasive fixation includes percutaneous plate osteosynthesis, closed reduction and internal fixation with percutaneous cannulated screws, and arthroscopy-assisted reduction and internal fixation with percutaneous screws (Stasikelis et al. 1993; Müller and Sommer 2012; Puha et al. 2012; Tong et al. 2012; Ortmaier et al. 2015). Paluvadi et al. (2014) and Vidovic et al. (2015) used MIPO to treat distal tibial fractures, and reported good outcomes. Syed and Panchbhavi (2004) treated 7 patients with closed pilon fractures by using closed reduction and internal fixation with percutaneous cannulated screws, and reported excellent outcomes. The postoperative mean follow-up was 30.6 months, and the average score for ankle joint function was 90.8/100.

Joint fusion is rarely used in the initial treatment of fractures. It is only performed in patients with severe bone and soft tissue injury, especially those with ischemia, hypotension, multiple trauma, and serious neurological injuries (Crawford et al. 2014).

Arthroscopy and external fixators are used for the treatment of tibial pilon fractures, including AO type B and type C1-2 fractures. Cetik et al. (2007) treated a 42-year-old male patient with a tibial pilon fracture caused by high-energy trauma, with an arthroscopy-assisted unilateral external fixator and minimally invasive internal osteosynthesis. In this treatment, arthroscopy was used to reposition the fracture fragments and restore the joint surface, and the fracture fragments were fixed with screws immediately after being repositioned. The author believed that arthroscopy-assisted surgery combined with external fixator use and minimally invasive internal fixation was the optimal treatment for tibial pilon fractures, because external fixation could improve fracture alignment, arthroscopy could help restore the joint surface, and minimally invasive screws ensure fragment stability. Kralinger et al. (2003) also reported a case of closed distal tibial fracture (AO, C3) treated successfully with arthroscopy-assisted minimally invasive reduction and percutaneous screw fixation, and obtained a good outcome.

Atesok et al. (2011) published an investigation indicating that arthroscopy-assisted techniques in intra-articular fracture fixation are minimally invasive and have high accuracy, and have been successfully used for the treatment of fractures of the tibial plateau, tibial intercondylar eminence, tibial pilon, calcaneus, femoral head, glenoid, greater tuberosity, distal clavicle, radial head, coronoid, distal radius, and scaphoid. The main disadvantages of these techniques were the time-consuming and technically demanding nature of the procedures and the prolonged learning curve.

We believe that the major advantages of arthroscopy-assisted minimally invasive reduction with use of external fixators include a small wound, reduction under direct vision, and protection of the soft tissue and blood supply to the fractures. An external fixator provides indirect reduction and an effective operating space for arthroscopic implantation, especially for AO type B fractures and partial C1 fractures. This method has not been proven to be effective in the treatment of B3 and C3 fractures in clinical practice.

This study still has some limitations; for example, this method has not been compared with other traditional internal fixation methods, and few cases of tibial pilon fractures have been treated with arthroscopy-assisted minimally invasive reduction with the use of external fixators.

References

Atesok K, Doral MN, Whipple T, Mann G, Mei-Dan O, Atay OA, Beer Y, Lowe J, Soudry M, Schemitsch EH (2011) Arthroscopy-assisted fracture fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:320–329

Cetik O, Cift H, Ari M, Comert B (2007) Arthroscopy-assisted combined external and internal fixation of a pilon fracture of the tibia. Hong Kong Med J 13:403–405

Crawford B, Watson JT, Jackman J, Fissel B, Karges DE (2014) End-stage hindfoot arthrosis: outcomes of tibiocalcaneal fusion using internal and Ilizarov fixation. J Foot Ankle Surg 53:609–614

Huebner EJ, Iblher N, Kubosch DC, Suedkamp NP, Strohm PC (2014) Distal tibial fractures and pilon fractures. J Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 81:167–176

Japjec M, Staresinić M, Culjak V, Vrgoc G, Sebecić B (2013) The role of external fixation in displaced pilon fractures of distal tibia. Acta Clin Croat 52:478–484

Klaue K, Cronier P (2015) Pilon fractures. Unfallchirurg 118:795–801

Kralinger F, Lutz M, Wambacher M, Smekal V, Golser K (2003) Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction and percutaneous screw fixation of a Pilon tibial fracture. Arthroscopy 19:E45

Krettek C, Bachmann S (2015a) Pilon fractures. Part 1: Diagnostics, treatment strategies and approaches. Chirurg 86:87–101

Krettek C, Bachmann S (2015b) Pilon fractures. Part 2: Repositioning and stabilization technique and complication management. Chirurg 86:187–201

Mazur JM, Schwartz E, Simon SR (1979) Ankle arthrodesis. Long-term follow-up with gait analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 61:964–975

McFerran MA, Smith SW, Boulas HJ, Schwartz HS (1992) Complications encountered in the treatment of pilon fractures. J Ortop Trauma 6:195–200

Müller TS, Sommer C (2012) Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis of the distal tibia. Oper Orthop Traumatol 24:354–367

Ortmaier R, Filzmaier V, Hitzl W, Bogner R, Neubauer T, Resch H, Auffarth A (2015) Comparison between minimally invasive, percutaneous osteosynthesis and locking plate osteosynthesis in 3-and 4-part proximal humerus fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16:297

Paluvadi SV, Lal H, Mittal D, Vidyarthi K (2014) Management of fractures of the distal third tibia by minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis—a prospective series of 50 patients. J Clin Orthop Trauma 5:129–136

Pollak AN, McCarthy ML, Bess RS, Agel J, Swiontkowski MF (2003) Outcomes after treatment of high energy tibial piafond fractrures. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 85-A:1893–1900

Puha B, Veliceasa B, Alexa O (2012) Minimally invasive percutaneous screws osteosynthesis indications in tibial pilon fractures. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 116:532–535

Schweigkofler U, Benner S, Hoffmann R (2015) Pilon fractures. Z Orthop Unfall 153:335–354

Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr (2004) A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of comples pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 18:S32–S38

Stasikelis PJ, Calhoun JH, Ledbetter BR, Anger DM, Mader JT (1993) Treatment of infected pilon nonunions with small pin fixators. J Foot Ankle 14:373–379

Syed MA, Panchbhavi VK (2004) Fixation of tibial pilon fractures with percutaneous cannulated screws. J Injury 35:284–289

Teeny SM, Wiss DA (1993) Open reduction and internal fixation of tibial plafond fractures. Variables contributing to poor results and complications. Clin Ortop 292:108–117

Tong D, Ji F, Zhang H, Ding W, Wang Y, Cheng P, Liu H, Cai X (2012) Two-stage procedure protocol for minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis technique in the treatment of the complex pilon fracture. Int Orthop 36:833–837

Vidović D, Matejčić A, Ivica M, Jurišić D, Elabjer E, Bakota B (2015) Minimally-invasive plate osteosynthesis in distal tibial fractures: results and complications. Injury 46:S96–S99

Watson JT, Moed BR, Karges DE, Cramer KE (2000) Pilon fractures. Treatment protocol based on severity of soft tissue injury. J Clin Orthop Relat Res 375:78–90

Authors’ contributions

HSL and LBC were the major contributors, and were responsible for article design, operative procedures, case collection, efficacy assessment after surgery, and drafting of the manuscript. KBL, SMP, JZ, and YY performed associated procedures, provided data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

All authors participated in this study, entitled “Minimally invasive treatment of tibial pilon fractures through arthroscopy and external fixator-assisted reduction.”

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Consent for publication

All patients consent to publish patient identifiable information and data was obtained.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Wuhan University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, H., Chen, L., Liu, K. et al. Minimally invasive treatment of tibial pilon fractures through arthroscopy and external fixator-assisted reduction. SpringerPlus 5, 1923 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3601-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3601-7