Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine sex differences across years in performance of runners in ultra-marathons lasting from 6 h to 10 days (i.e. 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 144, and 240 h). Data of 32,187 finishers competing between 1975 and 2013 with 93,109 finishes were analysed using multiple linear regression analyses. With increasing age, the sex gap for all race durations increased. Across calendar years, the gap between women and men decreased in 6, 72, 144 and 240 h, but increased in 24 and 48 h. The men-to-women ratio differed among age groups, where a higher ratio was observed in the older age groups, and this relationship varied by distance. In all durations of ultra-marathon, the participation of women and men varied by age (p < 0.001), indicating a relatively low participation of women in the older age groups. In summary, between 1975 and 2013, women were able to reduce the gap to men for most of timed ultra-marathons and for those age groups where they had relatively high participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The comparison of endurance performance between sexes has been a main topic of scientific research for decades (Lepers et al. 2013; Parnell 1954; Pate and Kriska 1984). Nowadays, women compete in the same endurance and ultra-endurance sports disciplines as men. However, this was not always the case. For example, women were considered too weak to compete in running competitions in the Olympic Games well into the twentieth century (www.olympic.org). When Kathrine Switzer competed in 1967 in the ‘Boston Marathon’ as the first woman ever to run an official marathon, she pretended to be a man to be able to run in the race (www.baa.org). Although she finished the race in 4:20 h:min well ahead of many men, the organizer of ‘Boston Marathon’ tried to remove her from the race. Only in 1972, women were officially accepted to compete in the ‘Boston Marathon’ (www.baa.org).

Once women were admitted to marathon running, the comparison of sex differences in marathon running started to attract scientific interest. Whipp and Ward (1992) and Tatem et al. (2004) especially focused on running results and both predicted that women would outrun men in the future. Whipp and Ward (1992) predicted that women would outrun men in marathon running in 1998 while Tatem et al. (2004) extrapolated 100 m Olympic running sprints results from 1904 to 2004 and projected women to overtake men in 100 m sprint in the 2156 Olympic Games. Since women entered the professional running world more than half a century later than men their improvements in performance were higher than in men in the first 30 years (Tatem et al. 2004; Whipp and Ward 1992). This triggered the conclusion that women would outrun men at some point as in 1998 (Whipp and Ward 1992) or in 2156 (Tatem et al. 2004). While women were be able to reduce the sex difference in performance in the second half of the twentieth century in running from 100 m to the marathon distance (Tatem et al. 2004; Whipp and Ward 1992), Holden (2004) found a newer trend of an increasing sex difference between 1989 and 2004. In the Olympic Games, in seven out of eight disciplines in running from 100 m to the marathon distance, the mean sex difference in performance increased from 10.4 to 11.0 %, with an exception of Paula Radcliffe’s world record in marathon running in 2003 (www.iaaf.org/home). It is worth to mention that the sex difference in world records in marathon running increased since then from 8.4 % in 2003 to 9.5 % in 2013 (www.iaaf.org/home).

The occasions where women were able to beat men in long-distance running events were very rare exceptions and happened only on recreational competitions, but never on professional competitions (Knechtle et al. 2008). Therefore, it seemed that women would, if at all, outrun men first in ultra-marathons as Pamela Reed did in the 2002 and 2003 ‘Badwater’ (www.badwater.com) or Hiroko Okiyama in the 2007 ‘Deutschlandlauf’ (www.deutschlandlauf.com). Although ultra-marathons are held all over the world, official World Championships exist only for 100 km ultra-marathons (www.iaaf.org/home). Therefore, the world’s elite in ultra-running may not compete in a single race where women might outrun men. In running races up to the marathon distance, results of World Championships, Olympic Games or a World Major Series can be compared among each other. In ultra-marathons, however, race results cannot be compared because races are not standardized due to different environmental conditions such as differences in race courses and differences in changes in altitude. Generally, events over different distances with different altitude gain or differences in course profiles cannot be compared properly. Therefore, in our opinion, the best possibility to investigate trends in ultra-marathon running performance with sex difference needs to include all existing races over a certain distance or duration.

A study including the longest ultra-marathons events held up to 10 days is required to evaluate the ongoing question whether women would outrun men in ultra-marathons. In this context, the aim of the present study was to examine sex differences across time in runners of ultra-marathons varying from 6 h to 10 days with the hypothesis that women would reduce the gap to men in the last decades.

Methods

Ethics

All procedures used in the study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanton St. Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent of the participants given the fact that the study involved the analysis of publicly available data.

Data sampling and data analysis

The data set for this study was obtained from the race website of the ‘Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung’ (DUV) (www.ultra-marathon.org). This website records all race results of all ultra-marathons held worldwide. Data of all competitors who ever participated in a 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 h, 6 days (144 h) and 10 days (240 h) ultra-marathon held worldwide between 1975 and 2013 were analysed. In time-limited races, athletes perform laps which are counted by lap counters or electronically. Any competitor is listed in the rankings as soon as she/he has completed one lap as minimum distance.

Statistical analysis

We used a multiple linear regression to analyse the gap between men and women (Table 1). To explore which variables may be accounted for, regression distances were graphically displayed against the variables (Fig. 1a, b). Due to the large amount of observations we used smoothing methods (i.e. loess if number of observations <1000 otherwise splines both implemented in the statistical software). The 95 % confidence regions are displayed and the polynomial fit for each ultra-marathon (UM) was added. We included the following variables in the model: sex, age at performance and calendar year of performance. To consider finishers who performed several races we included finisher as random variable in the model, although 48.9 % of the finishers in the data have only one finish. We justified including finisher as random variable by comparing the graphics of distance against age of the finisher with only one known finish with the finishers who have at least five finishes. Both graphs showed similar tendencies (graphs not shown). Visual inspection of Fig. 1a, b suggests using a cubic, quadratic and a cubic relation for age and year. To study the effect of sex we included also interactions. We also considered the heterogeneous variance of each UM-level. The final method was selected by Akaike information criterion (AIC) and visual inspection of the fitted values (Fig. 2a, b).

The final mixed model (1) was:

Distance is in km, ID is the identification number of the finisher, age is centered with 46 years (mean) and calendar year with 2007 (mean). Reference levels are for ultra-marathon 6 h and for sex male. To study the effect of sex according to age, years, and ultra-marathon we used estimated coefficient which has a p < 0.05 and computed the percentage difference of achieved km between man and women for each ultra-marathon, age and calendar year (Table 2). In addition, a Chi square test examined the variation of finishes of women and men by age group. The magnitude of the association between sex and age group was evaluated by Cramer’s V, which was interpreted as very low (less than 0.20), low (0.20–0.39), modest (0.40–0.69), high (0.70–0.89) or very high association (0.90–1.00) (Bryman and Cramer 2011). The statistical analysis and graphical outputs were performed using the statistical software R, version 3.1.2 (R Development Core Team 2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, ISBN 3-900051-07-0, www.R-project.org.

Results

Data of 32,187 finishers with 93,109 finishes were available. After excluding finishers with missing age, a total of 27,430 finishers and 86,508 finishes were available corresponding to a reduction of 14.8 and 7.1 %, respectively. Sex of one finisher was corrected in the case of a runner who had three runs, twice as female and one as male, assuming that she was female. Each finish should reach a minimum distance of 8, 11, 16, 22, 27, 38, and 49 km for 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 144, and 240 h, respectively, to be included in the analysis sample, which was the case for all finishes.

Overall, 20.7 % of the finishes were performed by women and 79.3 % by men. Among all finishers, 21.7 % were women and 78.3 % were men. A total of 48.9 % of the finishers performed only one finish, 19.0 % performed two finishes and the rest of the finishers achieved three or more successful finishes during the whole period of observation (Table 3). Across calendar years, the number of finishes increased for both women and men for all events. For both women and men, most of the finishes were achieved at the age of 30–50 years (Figs. 3, 4).

The average distance for men in 2007 with five finishes and an age of 46 years was 55.7, 90.1, 143, 222, 275, 519, and 833 km for 6, 12, 24, 72, 144, and 240 h, respectively (Table 2). With increasing age, the sex gap for all race durations increased (Table 2, negative values mean less distance achieved than men whereas positive values mean more distance). Across calendar years, the gap between women and men decreased in 6, 72, 144 and 240 h, but increased in 24 and 48 h (Table 2). For the 1997 and 2007 calendar year at age 46 in the 48 h UM women performed better than men (+3.7 and 3.3 %).

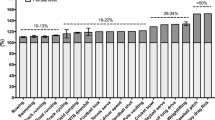

The men-to-women ratio was calculated for each age group for all races (Table 4; Fig. 5). A Chi square test was performed to examine the relationship between sex and age group, i.e. whether men-to-women ratio varied by age, for each race duration. The relationship between these variables was significant for all race durations: χ2 = 193.2, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.09 in 6 h, χ2 = 166.3, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.09 in 12 h, χ2 = 133.8, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.06 in 24 h, χ2 = 61.2, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.11 in 48 h, χ2 = 35.1, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.26 in 72 h, χ2 = 68.5, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.15 in 144 h, χ2 = 31.7, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.29 in 240 h. According to evaluation of Cramer’s V, the magnitude of the relationship between sex and age group was very low in 6, 12, 24, 48 and 144 h and low in 72 and 240 h. That was, the men-to-women ratio differed among age groups, where a higher ratio was observed in the older age groups, and this relationship varied by distance.

Discussion

This study intended to examine the sex difference for ultra-marathons held from 6 h to 10 days with the hypothesis that women would reduce the gap to men in the last decades. The most important findings were that (1) men were faster than women for all race durations, (2) the sex gap for all race durations increased with increasing age and (3) the gap between women and men decreased in 6, 72, 144 and 240 h, but increased in 24 and 48 h between 1975 and 2013.

Women were not able to narrow the gap to men with increasing race duration

A first important finding was that men were faster than women. The differences between women and men were between 0.2 and 10.0 % for all durations for calendar year 2007 (Table 2). However, these differences were lower than the general sex difference of 11–12 % reported for endurance and ultra-endurance performance (Cheuvront et al. 2005; Coast et al. 2004; Lepers and Cattagni 2012).

An approach of supporting the assumption of women outrunning men was reported by Speechly et al. (1996) comparing performances of both sexes in 90 km events, while matching marathon times of female and male runners. They found that women performed better than men in a 90 km event. Addressing the assumption of Speechly et al. (1996), Hoffman (2008) matched both sexes for running times in 50, 80 and 161 km in the same year and found no difference in running speed. It is important to mention that the runners investigated by Speechly et al. (1996) and Hoffman (2008) were matched for the running speed in shorter races. Therefore, the conclusion that women were as fast as men in ultra-marathon running is only partly true as no women exist who can be matched with the fastest men in the shorter running distances.

Sex differences in running performance have been shown to vary by race’s distance. For instance, Cheuvront et al. (2005) reported a sex difference of 8–14 % for running distances from 1500 m to 42 km, Lepers and Cattagni (2012) a sex difference of ~11 % in the ‘New York City Marathon’ from 1980 to 2009 and Coast et al. (2004) a sex difference of ~12.4 % in running distances from 100 m to 200 km. Across all these distances the sex difference in performance seemed rather to increase than to decrease with increasing race distance. The 240 h races belong to the longest races held worldwide (www.ultra-marathon.org) and therefore serve well for the statement that women will not outrun men in ultra-running distances.

The most important differences between women and men regarding running performance are differences in physiology and anthropometry. Women have more body fat than men in both elite (Vernillo et al. 2013) and recreational (Hoffman et al. 2010a, b) athletes. In elite runners both sexes are considerably leaner than recreational runners (Hetland et al. 1999). In both elite and recreational runners the percentage of body fat is higher in women compared to men (Blaak 2001). It could be argued that fatty tissue may be used as an energy reserve and this could be an advantage for ultra-distances since runners tend to lose body fat during multi-hours running competitions (Karstoft et al. 2013; Schütz et al. 2013). Women might benefit from their higher percentage of body fat since both sexes lose a similar amount of fat during an ultra-endurance performance such as a 100 km ultra-marathon (Knechtle et al. 2010a, b, 2012a, b). Another sex difference in anthropometry is the percentage of skeletal muscle mass (Holden 2004). In ultra-marathoners, both sexes have a lower body fat percentage and the percentage of skeletal muscle tissue is higher (Knechtle et al. 2010a, b, 2012a, b) than in recreational runners. However, body fat and training characteristics, not skeletal muscle mass, were associated with running times in half-marathoners, marathoners, and ultra-marathoners (Knechtle et al. 2012a, b).

Considering physiological aspects, maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) was considered as the most significant predictor of athletic performance (Bassett and Howley 2000). While elite male athletes reach a VO2max of ~85 ml min−1 kg−1 (Saltin and Astrand 1967), VO2max is lower in elite women with a maximum of ~70 ml min−1 kg−1 (Ridout et al. 2010). VO2max is mainly dependent from the heart’s performance and the lung capacity (Steding et al. 2010). The maximal cardiac output (Fomin et al. 2012) and the maximal lung capacity (Guenette et al. 2007) are higher in elite male compared to elite female athletes. VO2max depends directly from both maximal cardiac output and lung capacity and is therefore larger in men than in women (Steding et al. 2010).

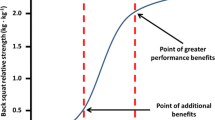

Another important aspect for running performance is running economy (Anderson 1996; Piacentini et al. 2013). Running economy is defined as the necessary effort to transport 1 kg of weight for 1 m (Morgan et al. 1989). Although there is a significant difference in running economy between elite and recreational runners, sexes show no difference (Morgan et al. 1989). Bassett and Howley (2000) found VO2max, body fat and running economy as the major three factors contributing and predicting running performance. Therefore, women are disadvantaged in two out of three factors and have no chance to outrun men.

The sex gap for all race durations increased with increasing age

A second important finding was that the sex differences in performance were larger in the older runners. This discrepancy among age groups should be attributed to the men-to-women ratio in each age group. This ratio increased consistently with increasing age for most of the race durations, i.e. a relatively lower number of women participated in the older age groups compared to men. An increase in sex difference in age group athletes has already been reported for athletes competing in shorter race distances. For age group pool swimmers and marathon runners, the sex difference increased with age. However, the increase in sex difference was lower in running compared to swimming (Senefeld et al. 2016). The increase in sex difference in these ultra-marathoners was due to the lower number of women in older age groups. This finding has already been reported for runners in short distances. For marathoners, the increase in sex difference with increasing age was explained by the lower number of women compared to men (Hunter and Stevens 2013).

The gap between women and men across calendar years

A third important finding was that the gap between the sexes decreased for certain ultra-marathons (i.e. 6, 72, 144 and 240 h) across years but increased for others (i.e. 24 and 48 h). Findings for a decrease in sex difference were reported over a large variety of distances as in 100 m sprints (Tatem et al. 2004), marathons (Whipp and Ward 1992) and ultra-marathons (Da Fonseca-Engelhardt et al. 2013; Eichenberger et al. 2012). Promoters of the theory that women would outrun men favoured linear models in performance to support their theory (Tatem et al. 2004; Whipp and Ward 1992). The use of linear models was, however, controversially discussed (Reinboud 2004) but mainly found to be worse than non-linear models.

A potential explanation for the increase in sex difference could be the participation in ultra-marathons. Several studies reported an increase in the percentage of female ultra-marathoners (Da Fonseca-Engelhardt et al. 2013; Hoffman et al. 2010a, b; Zingg et al. 2013). The first women officially ran a marathon in 1967 (www.baa.org). Forty-six years ago, the percentage of female overall finishers started to increase at the ‘Boston Marathon’ from less than 1 to 39.5 % (www.baa.org) as well as in other marathons (www.worldmarathonmajors.com). In ultra-marathons such as the ‘Western State 100 Mile Endurance Run’, the percentage of female finishers increased from virtually none in the late 1970s to nearly 20 % since 2004 (Hoffman et al. 2010a, b). Therefore, the density of both elite and recreational female finishers increased. Nevertheless, the density of the world’s fastest runners is still lower in women than in men (Deaner 2013). This leaves a possibility of a further decrease in the sex difference in ultra-running performance in case the number of female finishers will match with the number of male finishers.

The change in sex difference in performance differed between different distances (Bam et al. 1997; Tatem et al. 2004; Whipp and Ward 1992) as well as between elite and recreational runners (Hunter et al. 2011). As short and middle distance races up to 10,000 m have been held longer for both sexes in the Olympic Games, the first Olympic marathon for women was held in 1984 (www.olympic.org). Even later, women started to compete in ultra-marathons (www.ultra-marathon.org; Hoffman et al. 2010a, b). Therefore, the improvement of female performance would be faster in the first years than the improvement in men. While the sex difference in performance stabilized in running distances up to the marathon distance (Hunter et al. 2011), the sex difference in performance still decreased in ultra-marathons (Hoffman et al. 2010a, b).

Strength, weakness, limitations and implications for future research

The strength of the study is the inclusion of all athletes competing in ultra-marathons in duration between 6 h and 10 days. Furthermore, multiple finishes per athlete were included since the aspect of previous experience seems very important in ultra-marathon running (Hoffman and Parise 2015; Knechtle et al. 2009, 2011a, b). To the best of our knowledge, the data set is the most extensive for ultra-running in time-limited ultra-marathons so far. A possible weakness could be that some events from 6 h to 10 days were not recorded in the data base and therefore were not included in the data set. Furthermore, the study is limited since variables such as anthropometric characteristics (Knechtle et al. 2009, 2010a, b, 2011a, b), training data (Hagan et al. 1981), nutrition (Maughan and Shirreffs 2012; Rodriguez et al. 2009), fluid intake (Williams et al. 2012), exercise-associated hyponatremia (Hoffman et al. 2013), physiological parameters (Billat et al. 2001), and environmental conditions (Ely et al. 2007) were not considered. These variables may have had an influence on race outcome. Future studies may investigate the sex difference for all running distances from 60 m to 3100 miles for the world fastest women and men.

Practical applications

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study would have important practical implications for both researchers and practitioners working with long-distance runners. Since the analysed data were the most extensive ever studied in time-limited ultra-marathons and covered a large period (~40 years), the findings might be used in future studies as reference. Moreover, runners and practitioners working with them (e.g. fitness trainers) should consider the identified sex differences in the present study in order to develop sex-tailored training programs.

Conclusions

In time-limited races held during the 1975–2013 period, men were faster than women for all race durations, the sex gap for all race durations increased with increasing age and the sex gap decreased in 6, 72, 144 and 240 h, but increased in 24 and 48 h. Female ultra-marathoners seemed to be able to narrow the gap to men in some ultra-marathon race durations in the last 40 years. The men-to-women ratio differed among age groups, where a higher ratio was observed in the older age groups, and this relationship varied by distance.

References

Anderson T (1996) Biomechanics and running economy. Sports Med 22:76–89

Bam J, Noakes TD, Juritz J, Dennis SC (1997) Could women outrun men in ultramarathon races? Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:244–247

Bassett DR Jr, Howley ET (2000) Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:70–84

Billat VL, Demarle A, Slawinski J, Paiva M, Koralsztein JP (2001) Physical and training characteristics of top-class marathon runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33:2089–2097

Blaak E (2001) Gender differences in fat metabolism. Cur Opin Clin Nutr Metabol Care 4:499–502

Bryman A, Cramer D (2011) Quantitative data analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19—a guide for social scientists east sussex. Routdedge, UK

Cheuvront SN, Carter Iii R, Deruisseau KC, Moffatt RJ (2005) Running performance differences between men and women: an update. Sports Med 35:1017–1024

Coast JR, Blevins JS, Wilson BA (2004) Do gender differences in running performance disappear with distance? Can J Appl Physiol 29:139–145

Da Fonseca-Engelhardt K, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Lepers R, Rosemann T (2013) Participation and performance trends in ultra-endurance running races under extreme conditions—’Spartathlon’ versus ‘Badwater’. Extrem Physiol Med 2:1

Deaner RO (2013) Distance running as an ideal domain for showing a sex difference in competitiveness. Arch Sex Behav 42:413–428

Eichenberger E, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R (2012) Age and sex interactions in mountain ultramarathon running—the Swiss Alpine Marathon. Open Access J Sports Med 3:73–80

Ely MR, Cheuvront SN, Roberts WO, Montain SJ (2007) Impact of weather on marathon-running performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:487–493

Fomin Å, Ahlstrand M, Schill HG, Lund LH, Ståhlberg M, Manouras A, Gabrielsen A (2012) Sex differences in response to maximal exercise stress test in trained adolescents. BMC Pediatr 12:127

Guenette JA, Witt JD, McKenzie DC, Road JD, Sheel AW (2007) Respiratory mechanics during exercise in endurance-trained men and women. J Physiol 581:1309–1322

Hagan RD, Smith MG, Gettman LR (1981) Marathon performance in relation to maximal aerobic power and training indices. Med Sci Sports Exerc 13:185–189

Hetland ML, Haarbo J, Christiansen C (1999) Regional body composition determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry relation to training, sex hormones, and serum lipids in male long-distance runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports 8:102–108

Hoffman MD (2008) Ultramarathon trail running comparison of performance-matched men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:1681–1686

Hoffman MD, Parise CA (2015) Longitudinal assessment of the effect of age and experience on performance in 161-km ultramarathons. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 10:93–98

Hoffman MD, Lebus DK, Ganong AC, Casazza GA, Loan MV (2010a) Body composition of 161-km ultramarathoners. Int J Sports Med 31:106–109

Hoffman MD, Ong JC, Wang G (2010b) Historical analysis of participation in 161 km ultramarathons in North America. Int J Hist Sport 27:1877–1891

Hoffman MD, Fogard K, Winger J, Hew-Butler T, Stuempfle KJ (2013) Characteristics of 161-km ultramarathon finishers developing exercise-associated hyponatremia. Res Sports Med 21:164–175

Holden C (2004) An everlasting gender gap? Science 305:639–640

Hunter SK, Stevens AA (2013) Sex differences in marathon running with advanced age: physiology or participation? Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:148–156

Hunter SK, Stevens AA, Magennis K, Skelton KW, Fauth M (2011) Is there a sex difference in the age of elite marathon runners? Med Sci Sports Exerc 43:656–664

Karstoft K, Solomon TP, Laye MJ, Pedersen BK (2013) Daily marathon running for a week-the biochemical and body compositional effects of participation. J Strength Cond Res 27:2927–2933

Knechtle B, Duff B, Schulze I, Kohler G (2008) The effects of running 1,200 km within 17 days on body composition in a female ultrarunner—Deutschlandlauf 2007. Res Sports Med 16:167–188

Knechtle B, Wirth A, Knechtle P, Zimmermann K, Kohler G (2009) Personal best marathon performance is associated with performance in a 24-h run and not anthropometry or training volume. Br J Sports Med 43:836–839

Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Knechtle P, Lepers R (2010a) Predictor variables for a 100-km race time in male ultra-marathoners. Percept Motor Skills 111:681–693

Knechtle B, Senn O, Imoberdorf R, Joleska I, Wirth A, Knechtle P, Rosemann T (2010b) Maintained total body water content and serum sodium concentrations despite body mass loss in female ultra-runners drinking ad libitum during a 100 km race. Asia Pacif J Clin Nutr 19:83–90

Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Lepers R (2011a) Personal best marathon time and longest training run, not anthropometry, predict performance in recreational 24-hour ultrarunners. J Strength Cond Res 25:2212–2218

Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Senn O (2011b) What is associated with race performance in male 100-km ultra-marathoners anthropometry, training or marathon best time? J Sports Sci 29:571–577

Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Wirth A, Rüst CA, Rosemann T (2012a) A faster running speed is associated with a greater body weight loss in 100-km ultra-marathoners. J Sports Sci 30:1131–1140

Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Rosemann T (2012b) Does muscle mass affect running times in male long-distance master runners? Asian J Sports Med 3:247–256

Lepers R, Cattagni T (2012) Do older athletes reach limits in their performance during marathon running? Age 34:773–781

Lepers R, Knechtle B, Stapley PJ (2013) Trends in triathlon performance: effects of sex and age. Sports Med 43:851–863

Maughan RJ, Shirreffs SM (2012) Nutrition for sports performance: issues and opportunities. Proc Nutr Soc 71:112–119

Morgan DW, Martin PE, Krahenbuhl GS (1989) Factors affecting running economy. Sports Med 7:310–330

Parnell RW (1954) The relationship of masculine and feminine physical traits to academic and athletic performance. Br J Med Psychol 27:247–251

Pate RR, Kriska A (1984) Physiological basis of the sex difference in cardiorespiratory endurance sports medicine. Int J Appl Med Sci Sport Exerc 1:87–89

Piacentini MF, De Ioannon G, Comotto S, Spedicato A, Vernillo G, La Torre A (2013) Concurrent strength and endurance training effects on running economy in master endurance runners. J Strength Cond Res 27:2295–2303

Reinboud W (2004) Linear models can’t keep up with sport gender gap. Nature 432:147

Ridout SJ, Parker BA, Smithmyer SL, Gonzales JU, Beck KC, Proctor DN (2010) Age and sex influence the balance between maximal cardiac output and peripheral vascular reserve. J Appl Physiol 108:483–489

Rodriguez NR, Di Marco NM, Langley S (2009) American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41:709–731

Saltin B, Astrand PO (1967) Maximal oxygen uptake in athletes. J Appl Physiol 23:353–358

Schütz UHW, Billich C, König K, Würslin C, Wiedelbach H, Brambs HJ, Machann J (2013) Characteristics, changes and influence of body composition during a 4486 km transcontinental ultramarathon: results from the Transeurope Footrace mobile whole body MRI-project. BMC Med 11:1

Senefeld J, Joyner MJ, Stevens A, Hunter SK (2016) Sex differences in elite swimming with advanced age are less than marathon running. Scand J Med Sci Sports 26:17–28

Speechly DP, Taylor SR, Rogers GG (1996) Differences in ultra-endurance exercise in performance-matched male and female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28:359–365

Steding K, Engblom H, Buhre T, Carlsson M, Mosén H, Wohlfart B, Arheden H (2010) Relation between cardiac dimensions and peak oxygen uptake. J Cardiovasc Magnet Reson 12:1

Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Atkinson PM, Hay SI (2004) Momentous sprint at the 2156 Olympics? Nature 431:525

Vernillo G, Schena F, Berardelli C, Rosa G, Galvani C, Maggioni M, La Torre A (2013) Anthropometric characteristics of top-class Kenyan marathon runners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 53:403–408

Whipp BJ, Ward SA (1992) Will women soon outrun men? Nature 355:25

Williams J, Tzortziou-Brown V, Malliaras P, Perry M, Kipps C (2012) Hydration strategies of runners in the London marathon. Clin J Sport Med 22:152–156

Zingg MA, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R (2013) Analysis of participation and performance in athletes by age group in ultramarathons of more than 200 km in length. Int J Gen Med 6:209–220

Authors’ contributions

BK and MZ collected all data, BK, MZ and PN drafted the manuscript, FV and PN performed the statistical analyses, MZ, CR and TR participated in the design and coordination and helped drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Knechtle, B., Valeri, F., Nikolaidis, P.T. et al. Do women reduce the gap to men in ultra-marathon running?. SpringerPlus 5, 672 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2326-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2326-y