Abstract

This study sought to determine the diagnostic utility of perfusion parameters derived from dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) perfusion MRI with a short acquisition time (approximately 3.5 min) in patients with glioma, brain metastasis, and primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL).

Twenty-six patients with 29 lesions (4 low-grade glioma, 13 high-grade glioma, 7 metastasis, and 5 PCNSL) underwent DCE-MRI in a 3 T scanner. A ROI was placed on the hotspot of each tumor in maps for volume transfer contrast K trans, extravascular extracellular volume V e , and fractional plasma volume V p . We analyzed differences in parameters between tumors using the Mann–Whitney U test. We calculated sensitivity and specificity using receiver operating characteristics analysis.

Mean K trans values of LGG, HGG, metastasis and PCNSL were 0.034, 0.31, 0.38, 0.44, respectively. Mean Ve values of each tumors was 0.036, 0.57, 0.47, 0.96, and mean Vp value of each tumors was 0.070, 0.086, 0.26, 0.17, respectively. Compared with other tumor types, low-grade glioma showed lower K trans (P < 0.01, sensitivity = 88%, specificity = 100%) and lower V e (P < 0.01, sensitivity = 96%, specificity = 100%). PCNSL showed higher V e (P < 0.01, sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 88%), but the other perfusion parameters overlapped with those of different histology.

Kinetic parameters derived from DCE-MRI with short acquisition time provide useful information for the differential diagnosis of brain tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The differential diagnosis of brain tumor is critical to determining optimal therapy and estimating prognosis (DeAngelis 2001). High grade glioma, brain metastasis, and primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) are common types of brain malignancies in adults and can sometimes present similar results on conventional MR imaging (Ma et al. 2010). Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging, which allows for noninvasive evaluation of tumor vascularity, has been widely used to assess the physiology of brain tumor vascularity (Tofts 1996; Tofts et al. 1999).

Dynamic acquisition of images during contrast enhancement allows for the specific descriptive parameters related to local microvasculature characteristics to be calculated. Both relaxivity (T1)- and susceptibility (T2*)-based approaches have demonstrated good potential for measuring the characteristics of tumor vasculature (Quarles et al. 2012). Methods to assess changes in tissue T1 following contrast agent injection are commonly termed DCE-MRI and have been widely performed to assess microvascular permeability (Tofts 1996; Tofts et al. 1999). In DCE-MRI, the signal intensity change can be measured with sufficient temporal resolution and is related to tissue contrast agent concentration.

The pharmacokinetic (PK) model introduced by Tofts et al. can also be used to calculate volume transfer contrast K trans, volume of extravascular extracellular space V e , and fractional plasma volume V p (Tofts 1996; Tofts et al. 1999). As such, DCE-MRI can provide information on the blood microcirculation of tumors that cannot be acquired from conventional MRI (Tofts 1996; Tofts et al. 1999; Patankar et al. 2005; Xyda et al. 2012; Sorensen et al. 2009; Bisdas et al. 2011; Mills et al. 2006). In the brain, previous studies have used these kinetic parameters to evaluate glioma grade (Patankar et al. 2005), differential diagnosis (Xyda et al. 2012), treatment effects in primary brain tumors (Sorensen et al. 2009), diagnosing recurrence from radiation injury (Bisdas et al. 2011) and predicting prognosis (Mills et al. 2006).

DCE data measured with sufficient temporal resolution and acquisition time can provide useful results in PK model analysis (Tofts 1996; Larsson et al. 2013). Acquisition times of over 5 min have been used for the diagnosis of brain tumors in recent years (Bisdas et al. 2011; Aref et al. 2008; Awasthi et al. 2012; Bagher-Ebadian et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2012) and are recommended to maintain reliability (Larsson et al. 2013). But due to practical time limitations for an MRI examination, a DCE sequence with a short acquisition time and high diagnostic performance is required. Although DCE sequences with short acquisition times result in overestimated K trans and underestimated V e and V p , the resultant error is not so large at acquisition times of 3–4 min. Further, when using the same DCE protocol for different tumor types, parametric errors occur in the same direction, so their resulting distributions could be unchanged and diagnostic utility is preserved. In fact, there have been investigations on brain, head and neck, and breast neoplasms using DCE sequences of less than 5 min and the Tofts model (Awasthi et al. 2012; El Khouli et al. 2011; Shukla-Dave et al. 2012). Additionally, for use in clinical practice, reduced operation time is important and can be achieved with automated post-processing and fixed T1 method (Haacke et al. 2007), which uses preselected T1 value as a precontrast T1 value (T10) of the target organ to reduce the noise derived from T1 map and to reduce total acquisition time.

Against this background, the main purpose of this study was to investigate the diagnostic utility of DCE-MRI in diagnosing glioma, metastasis, and PCNSL tumors using a relatively short acquisition time and to reduce operation time using automated post-processing and a fixed T1 method.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the university hospital of Tokushima clinical trial center for developmental therapeutics, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment.

Patients

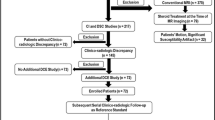

Fifty-two consecutive patients who underwent contrast-enhanced MRI for diagnosing suspected brain tumor between December 2012 and December 2013 were eligible for this study. From this group, those with glioma, metastasis, and PCNSL were included in the analysis. Diagnosis was made histologically or clinicoradiologically. Clinicoradiological diagnosis was made by consensus of two experienced neuroradiologists. Metastases were defined as newly emerging nodules in cancer patients; and recurrence of glioma were defined as a steady increase in contrast enhanced T1-weighted images. MRI follow-up was performed at 2-month intervals or sooner. Twenty-six patients (17 men and 9 women; mean age 61 years, age range 35–84,years; 29 lesions) were included in the analysis. The time from examination to diagnosis was recorded. We divided tumors into four groups: low grade glioma (LGG), high grade glioma (HGG), metastasis, and PCNSL. Table 1 summarizes the patient information.

Imaging protocol

Examinations were performed with a 3 T MR scanner (Discovery 750, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) using a standard eight-channel head coil. Pre-contrast T1-weighted images, T2-weighted images, diffusion-weighted images, arterial spin labeling images, and MR spectroscopy were acquired. Subsequently, DCE-MRI and post-contrast T1-weighted images were acquired with contrast agent (Gd-DTPA, 0.1 mmol/kg; Magnevist, Bayer HealthCare, Berlin, Germany). We performed 3D T2*-weighted angiography and DTI in selected patients.

DCE-MRI was acquired using a 3D fast spoiled gradient echo sequence with TR = 4.4 ms, TE = 1 ms, flip angle = 12°, field of view = 300 × 210 mm, matrix = 128 × 90, slice thickness = 8 mm, and number of slices = 16, consisting of 64 phases with a temporal spacing of 3.3 s. We chose TR, TE, and flip angle in accordance with those of an ordinary spoiled gradient echo sequence. Total scan time was 3 min and 31 s. A gadolinium-contrast agent was injected with a power injector (Medrad, Indianola, PA) at a rate of 2.5 ml/s after two cycles of dynamic scan. Immediately afterward, 20 ml of saline was injected at the same rate.

Image analysis

All imaging data were transferred from the scanner to a workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.6, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). We analyzed DCE data using the Tofts model implemented in the commercially available software GenIQ (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). We used 3-dimensional, rigid motion correction, which conduct a combination of rotational movement and translation in all cases. Referring to the temporal changes of the signal intensity of all voxel, the software automatically extracts the pixels that considered to arteries and veins. In the analysis, we used fixed T1 method (Haacke et al. 2007) and default T10 value (T10 = 1000 ms).

Data analysis

We selected enhanced lesions with a minor axis of more than twice the slice thickness (16 mm) and include them in the following analysis. In each map, we set an ROI of approximately 100 mm2 at the hot spot of the tumor. We measured average K trans, V e , and V p in each tumor. We then assessed the correlation of PK model parameters with different parametric maps and tumor histology.

Statistical analysis

We first calculated correlations between the DCE parameters K trans, V e , and V p using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. We then assessed the correlation between DCE parameters and tumor histology. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical difference between tumors was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Finally, we assessed the utility of K trans, V e , and V p in diagnosis of the brain tumors. From the results of this analysis, we selected a group of tumors with distinct PK parameters. We performed receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis for selected tumors to evaluate the optimal cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity.

All statistical analysis was performed using Excel Statistics 2012 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with Excel 2010 (Microsoft Co., Redmond, WA).

Results

The time from examination to diagnosis was 5 days (3 and 12 days: 25th and 75th percentiles). Data transfer and post-processing took approximately 10–12 min.

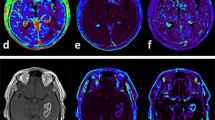

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging for a representative glioblastoma case (Figure 1) showed increased K trans, V e , and V p . There was an intermediate correlation between K trans and V e (R 2 = 0.41), while V p showed relatively weak correlations with K trans and V e (R 2 = 0.17 and 0.18, respectively)

Magnetic resonance imaging of a glioblastoma. A, Axial post-contrast T1-weighted image shows a ringed enhanced lesion in the left thalamus and subtle enhancement in the right thalamus. B, C, and D, Three kinetic parametric maps show increased vascular permeability (B; K trans map), leakage space (C; V e map), and plasma volume (D; V p map) corresponding to the enhanced area on the contrast-enhanced MRI.

LGG showed lower K trans and V e than the other malignant tumor types (P < 0.01). Among the other tumor types, K trans values overlapped. Lymphoma showed extremely high V e (P < 0.01), but V e for HGG and metastasis overlapped. No statistical differences were found for V p (Figure 2).

Area under the ROC curve for differentiating LGG and PCNSL was highest for V e (LGG: 0.97, PCNSL: 0.95). A cutoff value of K trans = 0.0848 for diagnosis of LGG provided the best good combination of sensitivity and specificity (0.88 and 1.0, respectively). A cutoff value of V e = 0.18 for diagnosis of LGG provided the best good combination of sensitivity and specificity (0.96 and 1.0, respectively). A cutoff value of V e = 0.912 for diagnosis of PCNSL provided the best combination of sensitivity and specificity (1.00 and 0.88, respectively).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that kinetic parameters acquired from DCE perfusion study with short acquisition time supplement conventional imaging in predicting tumor histology. This method takes only about 15 min (scan time of 3.5 min plus post-processing time of 10–12 min) and is not subject to operator-dependent bias, making it highly feasible in clinical settings.

K trans and V e demonstrated modest correlation with each other. V e was the most useful parameter in diagnosing LGG and PCNSL, while K trans was effective in differentiating LGG from the other tumors. V p failed to prove useful in differentiating brain tumor types in this study group.

Although the utility of the two-compartment PK model methods in brain tumor diagnosis has been reported (Patankar et al. 2005; Xyda et al. 2012; Sorensen et al. 2009; Bisdas et al. 2011; Aref et al. 2008; Awasthi et al. 2012; Bagher-Ebadian et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2012), it has not extended to clinical practice. One of the reasons for this is the long acquisition time. In the present study, we confirmed that the diagnostic performance of DCE analysis using a short acquisition time is comparable to that of methods in previous studies. We believe, therefore, that this method provides new and useful performance improvements for tumor diagnosis.

Another method, first-pass pharmacokinetic model (FPPM) analysis, can be performed from DCE analysis data with an ultra-short acquisition time of about 1 min (Li et al. 2000). K trans and V p can also be calculated with this method and are comparable to the data obtained from conventional PK model analysis (Harrer et al. 2004). Since, in the FPPM method, tracer concentration in arterial blood plasma is assumed to be much larger than that in the extravascular extracellular component, V e cannot be calculated (Li et al. 2000). Although conventional PK model analysis requires a longer acquisition time than the FPPM method, we believe the utility of V e in the diagnosis of brain tumors justifies the longer acquisition time of conventional PK model analysis.

Permeability indices, including K trans, have been shown in a number of earlier studies to correlate with glioma grade and to overlap between HGG, metastasis and Lymphoma (Xyda et al. 2012; Awasthi et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012; Johnson et al. 2004). Our findings are consistent with these previous studies. Since, the noninvasive estimation of vascular permeability using DCE-perfusion analysis can be useful not only for the diagnosis of the brain tumor (Xyda et al. 2012) but also the malignant potential of the tumor (Patankar et al. 2005), response to biological therapy (Checkley et al. 2003; Keunen et al. 2011), and prognosis (Mills et al. 2006), DCE perfusion imaging with a short acquisition time would contribute greatly to various clinical situations.

Previous studies have revealed that V e correlates with glioma grade (Awasthi et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012), and V e of lymphoma was higher than that of HGG (Johnson et al. 2004). The present results are in agreement with these previous studies, with V e showing the highest sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of LGG and PCNSL.

The physiological meaning of V e is still unclear. V e has been defined as “leakage space” in an initial study (Tofts 1996) and as extravascular extracellular space or its volume in later studies (Tofts et al. 1999). Aref et al. and Aryal et al. reported that interstitial volume fraction measured by DCE-MRI correlated with histologically measured extracellular space fraction in mammary tumor(Aref et al. 2008) and cerebral glioma models (Aryal et al. 2014) in rats. However, Mills et al. and Arlinghaus et al. reported that V e did not correlate with apparent diffusion coefficient in patients with brain glioblastoma (Mills et al. 2010) and breast cancer (Arlinghaus et al. 2011). Since apparent diffusion coefficient inversely correlates with tumor cellularity (Guo et al. 2002), these results are thought to contradict the correlation between V e and cellularity.

Additionally, V e was very high in lymphoma in the present study, which indicates large extravascular extracellular space fraction and low tumor cell density. However, PCNSL is generally a tumor with a high degree of cellularity (Guo et al. 2002). This indicates V e provides independent information about the tumor microenvironment. Further investigation involving radiological-pathological correlation is needed to reveal the true physiological meaning of V e .

In this study, V p did not contribute to the diagnosis of the brain tumors, which is somewhat surprising because new blood vessel proliferation in malignant tumors results in increased vascular density. We hypothesized that the V p of malignant tumors (i.e., HGG, metastasis, and PCNSL) would be higher than LGG, but there was no statistical difference. This preliminary study included a small number of patients and thus statistical power to detect such difference was weak. Further study is needed to determine the meaning of V p in the diagnosis of brain tumors.

There were other limitations in addition to the small number of patients sampled. We used a DCE-MRI sequence with a short acquisition time and could not compare our results with those from a longer acquisition time. Therefore, we could not evaluate precision of the kinetic parameters themselves. Another limitation was the existence of post-processing software-dependent bias. Kinetic parameters vary between post-processing software (Heye et al. 2013), and our results may have differed if we were to use different software. Finally, the DCE sequence parameters, fixed T1 method, contrast agent, and injection rate also influenced the results. If we were to perform the same experiment with different settings, the results should show the same tendency as in the present study but the kinetic parameters would be different.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the utility of DCE-MRI with a short acquisition time in the differential diagnosis of brain tumors. Operation time was also reduced using automatic vascular function detection and a fixed T1 method. With shortened times for image acquisition, analysis, and operation, the described method shows high feasibility for clinical use.

References

Aref M, Chaudhari AR, Bailey KL, Aref S, Wiener EC (2008) Comparison of tumor histology to dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging-based physiological estimates. Magn Reson Imaging 26(9):1279–1293

Arlinghaus LR, Li X, Rahman AR, Welch EB, Xu L, Gore JC, Yankeelov TE (2011) On the relationship between the apparent diffusion coefficient and extravascular extracellular volume fraction in human breast cancer. Magn Reson Imaging 29(5):630–638

Aryal MP, Nagaraja TN, Keenan KA, Bagher-Ebadian H, Panda S, Brown SL, Cabral G, Fenstermacher JD, Ewing JR (2014) Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI parameters and tumor cellularity in a rat model of cerebral glioma at 7 T. Magn Reson Med 71(6):2206–2214

Awasthi R, Rathore RK, Soni P, Sahoo P, Awasthi A, Husain N, Behari S, Singh RK, Pandey CM, Gupta RK (2012) Discriminant analysis to classify glioma grading using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and immunohistochemical markers. Neuroradiol 54(3):205–213

Bagher-Ebadian H, Jain R, Nejad-Davarani SP, Mikkelsen T, Lu M, Jiang Q, Scarpace L, Arbab AS, Narang J, Soltanian-Zadeh H, Paudyal R, Ewing JR (2012) Model selection for DCE-T1 studies in glioblastoma. Magn Reson Med 68(1):241–251

Bisdas S, Naegele T, Ritz R, Dimostheni A, Pfannenberg C, Reimold M, Koh TS, Ernemann U (2011) Distinguishing recurrent high-grade gliomas from radiation injury: a pilot study using dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Acad Radiol 18(5):575–583

Checkley D, Tessier JJ, Kendrew J, Waterton JC, Wedge SR (2003) Use of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to evaluate acute treatment with ZD6474, a VEGF signalling inhibitor, in PC-3 prostate tumours. Br J Cancer 89(10):1889–1895

DeAngelis LM (2001) Brain tumors. N Engl J Med 344(2):114–123

El Khouli RH, Macura KJ, Kamel IR, Jacobs MA, Bluemke DA (2011) 3-T dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of the breast: pharmacokinetic parameters versus conventional kinetic curve analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 197(6):1498–1505

Guo AC, Cummings TJ, Dash RC, Provenzale JM (2002) Lymphomas and high-grade astrocytomas: comparison of water diffusibility and histologic characteristics. Radiol 224(1):177–183

Haacke EM, Filleti CL, Gattu R, Ciulla C, Al-Bashir A, Suryanarayanan K, Li M, Latif Z, DelProposto Z, Sehgal V, Li T, Torquato V, Kanaparti R, Jiang J, Neelavalli J (2007) New algorithm for quantifying vascular changes in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI independent of absolute T1 values. Magn Reson Med 58(3):463–472

Harrer JU, Parker GJ, Haroon HA, Buckley DL, Embelton K, Roberts C, Baleriaux D, Jackson A (2004) Comparative study of methods for determining vascular permeability and blood volume in human gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging 20(5):748–757

Heye T, Davenport MS, Horvath JJ, Feuerlein S, Breault SR, Bashir MR, Merkle EM, Boll DT (2013) Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Part I. Perfusion characteristics in the female pelvis by using multiple computer-aided diagnosis perfusion analysis solutions. Radiol 266(3):801–811

Jia Z, Geng D, Xie T, Zhang J, Liu Y (2012) Quantitative analysis of neovascular permeability in glioma by dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. J Clin Neurosci 19(6):820–823

Johnson G, Wetzel SG, Cha S, Babb J, Tofts PS (2004) Measuring blood volume and vascular transfer constant from dynamic, T(2)*-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med 51(5):961–968

Keunen O, Johansson M, Oudin A, Sanzey M, Rahim SA, Fack F, Thorsen F, Taxt T, Bartos M, Jirik R, Miletic H, Wang J, Stieber D, Stuhr L, Moen I, Rygh CB, Bjerkvig R, Niclou SP (2011) Anti-VEGF treatment reduces blood supply and increases tumor cell invasion in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(9):3749–3754

Larsson C, Kleppesto M, Rasmussen I Jr, Salo R, Vardal J, Brandal P, Bjornerud A (2013) Sampling requirements in DCE-MRI based analysis of high grade gliomas: simulations and clinical results. J Magn Reson Imaging 37(4):818–829

Li KL, Zhu XP, Waterton J, Jackson A (2000) Improved 3D quantitative mapping of blood volume and endothelial permeability in brain tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging 12(2):347–357

Ma JH, Kim HS, Rim NJ, Kim SH, Cho KG (2010) Differentiation among glioblastoma multiforme, solitary metastatic tumor, and lymphoma using whole-tumor histogram analysis of the normalized cerebral blood volume in enhancing and perienhancing lesions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31(9):1699–1706

Mills SJ, Patankar TA, Haroon HA, Baleriaux D, Swindell R, Jackson A (2006) Do cerebral blood volume and contrast transfer coefficient predict prognosis in human glioma? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27(4):853–858

Mills SJ, Soh C, Rose CJ, Cheung S, Zhao S, Parker GJ, Jackson A (2010) Candidate biomarkers of extravascular extracellular space: a direct comparison of apparent diffusion coefficient and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging–derived measurement of the volume of the extravascular extracellular space in glioblastoma multiforme. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31(3):549–553

Patankar TF, Haroon HA, Mills SJ, Baleriaux D, Buckley DL, Parker GJ, Jackson A (2005) Is volume transfer coefficient (K(trans)) related to histologic grade in human gliomas? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26(10):2455–2465

Quarles CC, Gore JC, Xu L, Yankeelov TE (2012) Comparison of dual-echo DSC-MRI- and DCE-MRI-derived contrast agent kinetic parameters. Magn Reson Imaging 30(7):944–953

Shukla-Dave A, Lee NY, Jansen JF, Thaler HT, Stambuk HE, Fury MG, Patel SG, Moreira AL, Sherman E, Karimi S, Wang Y, Kraus D, Shah JP, Pfister DG, Koutcher JA (2012) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of outcome in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma patients with nodal metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82(5):1837–1844

Sorensen AG, Batchelor TT, Zhang WT, Chen PJ, Yeo P, Wang M, Jennings D, Wen PY, Lahdenranta J, Ancukiewicz M, di Tomaso E, Duda EG, Jain RK (2009) A "vascular normalization index" as potential mechanistic biomarker to predict survival after a single dose of cediranib in recurrent glioblastoma patients. Cancer Res 69(13):5296–5300

Tofts PS (1996) Optimal detection of blood–brain barrier defects with Gd-DTPA MRI-the influences of delayed imaging and optimised repetition time. Mag Reson Imaging 14(4):373–380

Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, Larsson HB, Lee TY, Mayr NA, Parker GJ, Port RE, Taylor J, Weisskoff RM (1999) Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging 10(3):223–232

Xyda A, Haberland U, Klotz E, Jung K, Bock HC, Schramm R, Knauth M, Schramm P (2012) Diagnostic performance of whole brain volume perfusion CT in intra-axial brain tumors: preoperative classification accuracy and histopathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol 81(12):4105–4111

Zhang N, Zhang L, Qiu B, Meng L, Wang X, Hou BL (2012) Correlation of volume transfer coefficient Ktrans with histopathologic grades of gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging 36(2):355–363

Acknowledgements

This study was supported with a grant from Bayer HealthCare, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TK, SN and MH conceived the study. YO, YM, KN, SI, YO, DK collected the data. TA and MM performed data analysis and interpretation. TA edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abe, T., Mizobuchi, Y., Nakajima, K. et al. Diagnosis of brain tumors using dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion imaging with a short acquisition time. SpringerPlus 4, 88 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0861-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0861-6