Abstract

A lack of convenient and reliable biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis is a common challenge for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Recent advancement in ultrasensitive protein assays has allowed the quantification of tau and phosphorylated tau proteins in peripheral plasma. Here we identified 66 eligible studies reporting quantification of plasma tau and phosphorylated tau 181 (ptau181) using four ultrasensitive methods. Meta-analysis of these studies confirmed that the AD patients had significantly higher plasma tau and ptau181 levels compared with controls, and that the plasma tau and ptau181 could predict AD with high-accuracy area under curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic. Therefore, plasma tau and plasma ptau181 can be considered as biomarkers for AD diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The lack of early diagnostic biomarkers for selecting prodromal or early-stage patients is one of the roadblocks in clinical trials. The National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) has recently proposed a research framework for AD and specified the importance of amyloid-beta (Aβ), tau, and neurodegeneration [AT(N)] in the biological definition of AD [1]. Although the Aβ- or tau-positron emission tomography (PET) has been developed, it is yet to be globally available, making the NIA-AA research framework challenging to put into practice. Therefore, it is urgent to discover convenient biomarkers with early-diagnostic significance.

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein localized primarily in neurons. It is also a primary component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), a pathological hallmark in AD [2]. The loss of normal functions and the gain of toxic functions of Tau have been linked with the pathogenesis of AD [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Mounting evidence has suggested that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of tau and phosphorylated tau are linearly associated with symptom severity of AD [8,9,10,11], suggesting tau as a promising biomarker for early diagnosis and prognostic prediction. However, clinical application of CSF biomarkers has been hindered by high cost, invasiveness, and side effects of lumbar punctures, such as positional headache [12].

The detection of tau in plasma has been limited due to its low abundance until recent technical development of ultrasensitive assays. The plasma tau or phosphorylated tau levels in the healthy population and diseased patients have been assessed using different technologies such as Single-molecule Array (Simoa) [13], ImmunoMagnetic Reduction (IMR) [14], enhanced immunoassay using multi-arrayed fiber optics conjugated with rolling circle amplification (a-EIMAF) [15] and Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) [16]. However, the plasma tau or phosphorylated tau levels vary among studies, and there is no cut-off threshold between AD and normal elderly. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we set out to determine the normal range of plasma tau and phosphorylated tau 181 (ptau181) levels in healthy populations stratified by age and sex, and investigate the cut-off thresholds of plasma tau and ptau181 between AD patients and controls.

Methods

Literature search

Literature search was performed in databases Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar by the date of January 21st, 2021, according to the methodology suggested by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17], using the following terms: Alzheimer disease, AD, dementia, Parkinson disease, PD, traumatic brain injury, TBI, plasma tau, plasma total tau, plasma phosphorylated tau, Simoa IMR, EIMAF, a-EIMAF, and MSD. Papers published in an online-first and ahead-of-print manner were included in the analysis. The protocol of the overarching project has been published (PROSPERO registration No. CRD42020151852).

Study selection

The analysis involved three questions. For Question 1, i.e., the normal range of plasma tau/ptau181 in healthy populations, the following criteria were applied: (1) full-text publications in English; and (2) plasma tau and/or ptau181 levels were measured by Simoa, IMR, EIMAF/a-EIMAF, or MSD. Studies were excluded if: (1) without sufficient data to allow for the extraction of plasma tau/ptau181 levels, or (2) the mean age of cohorts in the studies was < 18 years.

For Question 2, i.e., the differences of plasma tau/ptau181 between AD patients and controls, the following selection criteria were applied: (1) full-text publications in English; (2) plasma tau and/or ptau181 levels were measured by Simoa, IMR, EIMAF/a-EIMAF, or MSD; and (3) AD was diagnosed according to the 2011 core clinical NIA-AA [18] or the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association [19] guidelines. Studies were excluded if: (1) studies without sufficient data to allow for the extraction of plasma tau/ptau181 levels, (2) the mean age of cohorts in the studies was < 18 years, or (3) patients employed in the studies had other cognitive disorders (e.g., mild cognitive impairment [MCI], vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia).

Question 3 is to calculate the diagnostic accuracy of plasma tau/ptau181 for AD. For this, we analyzed all publications selected for Question 2, if the reported plasma tau/ptau181 were used for AD diagnosis in the original publications.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (XLD and STZ) performed the study assessment independently, and data were reported following the PRISMA statement [17]. Any discrepancy would be discussed with additional reviewers (LJJ and LW). Study quality was assessed using the modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [20]. A score of up to 8 points was assigned to each study based on the quality of population selection, the comparability between groups, and assessment of exposure. For studies with diagnostic tests, we assessed the quality of selected literature by checking items of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 tool (QUADAS-2) [21].

Statistical analysis and heterogeneity exploration

For the normal range of plasma tau or ptau181, the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the Random-effect model, which was used to presume that the true effect size varied among studies [21]. Subgroup analysis was performed according to age and sex ratio. For the diagnostic value of plasma tau or ptau181, the weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% CI was calculated between AD patients and controls with a random-effects model. To evaluate the diagnostic test accuracy, we used the diagnostic accuracy studies module [22] to calculate main outcome measures, including sensitivity and specificity, and the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). We then fitted a hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) model using a bivariate regression approach to visualize the relationship between sensitivity and specificity and calculated the area under curve (AUC). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 index. According to the Cochrane handbook, the heterogeneity was classified as low (I2 index 0%–40%), moderate (30%–60%), substantial (50%–90%), and considerable (75%–100%) [23, 24]. For heterogeneity exploration, meta-regression analysis was performed to evaluate the potential bias factors, while age, sample size, sex ratio, and region were included as four covariates. Furthermore, the results of meta-analyses were assessed by funnel plots and Egger’s test [25]. All calculations were carried out using statistical softwares provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (RevMan 5.1) and Stata14.1 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Study inclusions and quality assessment

The search strategy identified 4230 studies without duplication, and 2999 studies were excluded after abstract screening. Of the left 85 studies with full-text content, 19 studies were excluded as they were not a clinical study or lacked a clinical outcome description. Finally 66 studies were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Based on the modified NOS criteria [20], 53 studies were classified as high-quality, and 13 studies as medium-quality (Table S1). The revised QUADAS-2 [26] determined that the overall quality of studies included was robust. Most studies ranked as low bias and low applicability concern (Fig. S1).

The characteristics, including number of subjects, average age, male percentage, and plasma tau/ptau181 levels of the 66 studies are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Forty-one studies using Simoa (15,490 healthy controls), 15 studies using IMR (727 healthy controls), and two studies using a-EIMAF (189 healthy controls) were included for plasma tau studies. Twenty-two studies focused on AD, comprising 1456 patients with AD and 1973 controls. Only studies using Simoa (13 studies, 1189 AD patients and 1611 controls) and IMR (9 studies, 267 AD patients and 362 controls) were included for analysis since there were insufficient data for a-EIMAF. For ptau181, six studies using the Simoa - Karikari method (not the commercial p-tau181 version) (1424 healthy controls) and three using MSD (440 healthy controls) were included for the normal range analysis. Four studies using Simoa (392 AD patients and 773 controls) and three studies using MSD (231 AD patients and 440 controls) were identified for analysis related to AD diagnosis.

Plasma tau and ptau181 levels in healthy cohorts

Subgroup analysis was performed according to age and sex ratio, among studies using Simoa, IMR, a-EIMAF, and MSD, respectively. Based on the data retrieved, the average age of cohort stratification was classified as young (< 40 years old), middle-aged (40–60 years old), and old (> 60 years). The sex ratio was defined as low (less than 40% male), middle (40%–60% male), and high (over 60% male).

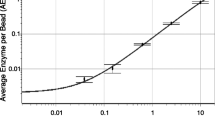

Among the 66 studies, 58 studies that used Simoa, IMR, or a-EIMAF were included for the analysis of normal range of plasma tau, as the MSD studies focused on CSF tau. Forty-one publications, reporting 42 cohorts, were retrieved using the Simoa technology [8, 27,28,29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, 46,47,48,49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, 91,92,93]. Our results indicated that the average plasma tau level in healthy populations was 3.07 pg/ml (95% CI 2.72–3.41, I2 = 99.7%, P < 0.0001). The plasma tau levels in the young, middle-aged, and old groups were 2.96 pg/ml (95% CI 2.20–3.72), 2.85 pg/ml (95% CI 2.22–3.47), and 3.23 pg/ml (95% CI 2.84–3.62), respectively (Fig. 2a), without significant differences (P = 0.099). However, significant differences were identified in the subgroup analysis by sex ratio (4.15 pg/ml vs 2.64 pg/ml vs 3.24 pg/ml; P < 0.0001; Fig. S2). Fifteen publications [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] reporting 20 cohorts were retrieved using IMR and two publications [82, 83] reporting four cohorts were retrieved using a-EIMAF. The effect sizes (ESs) for plasma tau levels were 16.30 pg/ml (95% CI 14.61–17.99, I2 = 92.7%, P < 0.0001, Fig. S3) and 76.14 fg/ml (95% CI 72.34–79.93, I2 = 88.8%, P < 0.0001, Fig. S4), respectively.

The levels of plasma tau and ptau181 in healthy people detected by the Simoa method. Meta-analysis of studies calculating plasma tau levels (a) and plasma ptau181 levels (b) of different age groups in the healthy population. In ptau181 studies, the average age in Rodriguez et al. was considerably higher; the control cohort used in Suarez-Calvet et al. comprised ‘middle-aged’ adults; the TRIAD cohort in Karikari et al. included young individuals; all of which may have contributed to the heterogeneity

Nine studies that used Simoa or MSD methods were included for the analysis of normal range of plasma ptau181. Six publications, reporting seven cohorts, were retrieved using the Simoa technology [45, 84,85,86,87,88], including 1424 healthy subjects. The ES for plasma ptau181 levels in healthy populations was 11.18 pg/ml (95% CI 9.68–12.68, I2 = 95.9%, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2b). There were no significant differences in plasma ptau181 level in the subgroup analysis concerning age (P = 0.181) or the sex ratio (P = 0.168, Fig. S2). Three publications [60, 89, 90] reporting five cohorts using the MSD method, including 440 healthy subjects who could not be grouped by age or sex ratio, were identified. The ES for plasma ptau181 levels measured by MSD was 2.48 pg/ml (95% CI 1.57–3.37, I2 = 97.0%, P < 0.0001; Fig. S4).

Plasma total tau and ptau181 in AD patients and controls

We then compared plasma tau and ptau181 between AD and controls. The random-effects model of meta-analysis with subgroup analysis was performed according to age and sex ratio. Among the 66 studies, 22 studies that used Simoa and IMR were included for the analysis of difference of plasma tau between AD and controls, and the number of studies that used other technologies was insufficient for analysis. For the Simoa method, 13 papers, reporting 14 cohorts [44, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], were retrieved with a total of 1189 AD patients with 1611 controls. Our analysis revealed a significantly higher plasma tau level in patients with AD, with an average WMD value of 0.61 (95% CI 0.36–0.86, I2 = 75.8%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3a). The WMDs for subgroups divided by different male compositions were 0.48 (< 40% male, 95% CI − 0.18–1.14), 0.99 (40%–60% male, 95% CI 0.54–1.44) and 1.30 (> 60% male, 95% CI 0.39–2.21), respectively, indicating a strong effect of sex on plasma tau levels in AD patients (Fig. S5). Meta-regression analysis identified that only the sample size significantly contributed to the high heterogeneity (P = 0.027, Table S2). The funnel plots and the Egger’s test suggested no publication bias (P = 0.133) (Fig. S6). Similarly, 9 papers [72,73,74, 76,77,78,79,80,81] reporting 11 cohorts using the IMR method (362 controls and 267 patients) were identified (Fig. S5), showing an average WMD value of 24.83 (95% CI 15.70–33.96, I2 = 98.9%, P < 0.0001). There was no publication bias (P = 0.175, Fig. S6), but the year of publication (P = 0.013) may influence the heterogeneity (Table S2).

Comparison of plasma tau or ptau181 between AD and healthy controls. Meta-analysis of studies comparing plasma tau (a) and ptau181 (b) levels between AD and healthy controls, detected by the Simoa method. In ptau181 studies, the study of O’connor et al. was a familial AD study; the average age in the study of Rodriguez et al. was considerably higher; the control cohort used in the study of Suarez-Calvet et al. comprised ‘middle-aged’ adults; the TRIAD cohort in Karikari et al. included young individuals, all of which may have contributed to the heterogeneity. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; WMD, weighted mean difference

Seven studies that used Simoa and MSD were included for the analysis of the plasma ptau181 difference between AD and controls. Four publications reporting five cohorts [45, 86,87,88] using the Simoa technology were retrieved, resulting in a total of 773 controls and 392 patients. The plasma ptau181 levels were significantly elevated in AD patients, with an average WMD value of 11.68 (95% CI 9.60–13.76, I2 = 64.9%, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3b). The funnel plots suggested no publication bias for plasma ptau181 (P = 0.635, Fig. S6). Similar results were found based on three papers reporting five cohorts [60, 89, 90] using the MSD method (440 controls and 231 patients), with a WMD of 3.53 (95% CI 1.97–5.09, I2 = 93.0%, P < 0.0001, Fig. S5). There was also no publication bias (P = 0.055, Fig. S6).

The diagnostic accuracy of plasma tau/ptau181 for AD

Among the 66 studies, four studies reporting five cohorts [44, 61, 64, 65] were pooled for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of plasma tau using the Simoa method. The estimate values of diagnostic accuracy are summarized in Table S3. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of plasma tau to predict AD were 0.75 (95% CI 0.60–0.86) and 0.69 (95% CI 0.57–0.79), respectively (Fig. 4a). The DOR was 6.16 (95% CI 3.02–12.53), and the AUC of the HSROC curve was 0.77 (95% CI 0.74–0.81) (Fig. 4b). Fagan’s nomogram showed that the probability of AD increased from 25% (pre-test probability) to 45% (post-test probability) when plasma tau level was above the threshold, while the probability of AD decreased to as low as 11% when plasma tau level was below the threshold (Fig. 4c).

Diagnostic accuracy of plasma tau and ptau181. a–c Forest plots of pooled sensitivity and specificity (a), HSROC curve (b), and Fagan’s nomogram (c) to estimate the clinical utility of plasma tau detected by the Simoa method. d–f The forest plots of pooled sensitivity and specificity (d), HSROC curve (e) and Fagan’s nomogram (f) to estimate the clinical utility of plasma ptau181 detected by the Simoa method

Four studies using the Simoa method reporting five cohorts [45, 86,87,88] were pooled for meta-analysis to test the diagnostic accuracy of plasma ptau181. The estimate values of diagnostic accuracy are summarized in Table S3. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of ptau181 were 0.89 (95% CI 0.81–0.93) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.79–0.91), respectively (Fig. 4d). The DOR was 46 (95% CI 18–123), and the AUC of the HSROC curve was 0.93 (95% CI 0.91–0.95) (Fig. 4e). The probability of AD increased from 25% (pre-test probability) to 67% (post-test probability) when plasma ptau181 level was above the threshold and decreased to as low as 4% when plasma ptau181 level below the threshold (Fig. 4f). Consistently, two studies using the MSD method reporting four cohorts [89, 90] were pooled for meta-analysis. The estimate values of diagnostic accuracy are summarized in Table S3. The pooled sensitivity of ptau181 was 0.87 (95% CI 0.78–0.92), and the pooled specificity was 0.79 (95% CI 0.73–0.83, Fig. S7). The DOR was 23.98 (95% CI 10.14–56.69), and the AUC of the HSROC curve was 0.86 (95% CI 0.83–0.89, Fig. S7). The probability of AD increased from 25% (pre-test probability) to 58% (post-test probability) when plasma ptau181 level was above the threshold, and decreased to 5% when plasma ptau181 level was below the threshold (Fig. S7).

Discussion

With a growing interest in plasma tau detection during the last 10 years, heterogeneity between studies has been consistently presented. Besides, given the inconsistency between publications regarding the plasma tau levels in AD (compared to control), it is difficult to determine the suitability of plasma tau/ptau181 to predict AD. In this meta-analysis, we found that both plasma tau and ptau181 have diagnostic values, and both of them are significantly higher in AD patients than in controls. We also established the average plasma tau and ptau181 levels based on the current literature, which may be used as a reference point in future research.

Currently, there are four ultrasensitive assays that can be used for plasma tau and ptau detection. In this meta-analysis, we examined them independently. Despite the differences in absolute values of plasma tau and ptau, results from all assays support the notion that both plasma tau and ptau181 are elevated in AD compared with healthy controls. Based on the available publications of each method, we have been able to calculate the sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy for AD of studies using Simoa (tau AUC: 0.77; ptau181 AUC: 0.93), and MSD methods (ptau181 AUC: 0.86), while the other two methods had limited applications in AD research.

Both Aβ and tau can now be visualized in the brain using PET and be measured in the CSF. Although medical history and cognitive and neurologic examinations remain the most important diagnostic tool in the clinic [94], these new techniques can assist the diagnosis of AD [1]. However, the associated cost and infrastructure requirements have limited their use, especially in developing countries. It is critical to accurately measure AD-associated proteins in plasma and determine their relationships with brain and CSF contents. Proteins in plasma may reflect protein levels in the brain and CSF, especially in the state of illness. For example, the correlation between CSF and plasma ptau181 is significant in PET Aβ-positive cases, even without cognitive impairment [90]. Higher ptau181 is associated with increased standardized uptake value ratio of tau PET in Braak I–IV regions of interest [89]. Furthermore, our meta-analysis results reflected the high diagnostic accuracy of plasma tau (AUC 0.77, 95% CI 0.74–0.81) and ptau181 (AUC 0.93, 95% CI 0.91–0.95), similar to the diagnostic accuracy of tau PET (AUC 0.98, 95% CI 0.94–1.00) and CSF ptau181 (AUC 0.97, 95% CI 0.92–1.00) [90]. In contrast, there is only a weak association between CSF and plasma tau, as confirmed by two independent studies [46, 65], suggesting that they may go through different metabolism. There are no significant differences in plasma or serum Aβ between AD and controls, and plasma Aβ may reflect peripheral Aβ generation instead of brain pathology [95].

In addition, the current meta-analysis supports plasma ptau181 as a better predictive biomarker than plasma tau for AD. The difference in plasma ptau181 between AD and controls was greater than plasma tau in our analysis (WMD: 11.68 pg/ml vs 0.83 pg/ml), and the pooled diagnostic accuracy of ptau181 was also higher (AUC: 0.93 vs 0.77). These are consistent with a previous report that the plasma ptau181 is more strongly associated with both Aβ and tau PET than plasma tau [60], and can differentiate AD from non-AD pathologies with high accuracy (AUC 97.4, 95% CI 94.1%–100%) eight years before death [87], collectively highlighting the potential of ptau181 as a biomarker for AD pathology.

We also found a higher level of plasma ptau181 compared to total tau in the meta-analysis. Phosphorylation is a post-translational modification of the protein, and theoretically, ptau181 should be a portion of total tau in any given tissue [96]. However, according to our analysis of publications based on the Simoa method, the mean level of ptau181 was higher than total tau (11.18 pg/ml vs 3.07 pg/ml). There could be differences in calibration standard, and at this stage, it is not feasible to compare the calculated values of tau and ptau181.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The ultrasensitive measurement of plasma tau has yet to be extensively tested, leading to high heterogeneity in the results. Meta-regression analyses suggested that the heterogeneity was partly explained by the sample size of studies included. In addition, most of the studies included in the current analysis used clinical diagnostic guidelines rather than gold-standard autopsy-confirmed AD, which can induce heterogeneity. One study [57] on neuropathologically confirmed autopsy cases has revealed a greater change in plasma tau (WMD 5.81), compared to the results from the clinically diagnosed cases (WMD 0.83), highlighting the potential error induced by diagnosis. Even the diagnosis is correct, AD itself can be heterogenetic. For example, familial cohorts [86] may lead to different results from sporadic cohorts.

On the other hand, due to the lack of information on ApoE4 status, we could not measure the impact of ApoE on plasma tau and ptau, leading to potential heterogeneity. We have considered age as a factor for heterogeneity, but due to the limited data, we can only analyze the effect of age in healthy populations, where we found no effect of age on plasma tau. Future analysis should be performed when there are more studies on early-onset AD.

We excluded a few publications for analysis. Two using the Simoa platform were excluded as the methods used in those studies had not been validated in multiple cohorts or studies [97], or were specifically validated for CSF (not plasma) [61]. Although results of the two studies are consistent with our findings, it is challenging to combine them with those using the commercialized plasma tau detection kit developed by Quanterix. A few other studies were focused on the serum tau or ptau [98, 99], and were also excluded from our analysis.

We have to mention that some studies on ptau181 were recently published during the final revision of the manuscript, and were not included. These latest studies have investigated the dynamic changes of plasma ptau181 across the AD spectrum [100] and the relationship between polygenic risk scores for AD and plasma ptau181 [101]. They have also compared performance of ptau181 with other biomarkers in AD and MCI prediction [102] or amyloid PET status prediction [103]. In addition, ptau217 [104] and ptau231 (Ashton et al. in press) have been reported recently to differentiate AD from other neurodegenerative disorders and be associated with tau pathology in the brain. The plasma ptau217 may out-perform ptau181 with a higher AUC and stronger correlations with the tau PET [9, 104]. However, here we did not include plasma ptau217 and ptau231 studies in our meta-analysis, due to the limited number of publications.

Conclusion

In summary, the results presented provide preliminary evidence of plasma tau and its phosphorylated form ptau181 as potential biomarkers for neurological diseases, especially for AD diagnosis, which may facilitate drug discovery of these diseases by selecting correct patients for clinical trials.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ptau181:

-

Phosphorylated tau 181

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- NIA-AA:

-

National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s Association

- Aß:

-

Amyloid-beta

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- NFT:

-

Neurofibrillary tangle

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- Simoa:

-

Single-molecule Array

- IMR:

-

ImmunoMagnetic Reduction

- a-EIMAF:

-

multi-arrayed fiber optics conjugated with rolling circle amplification

- MSD:

-

Meso Scale Discovery

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- QUADAS-2:

-

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 tool

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference

- DOR:

-

Diagnostic odds ratio

- HSROC:

-

Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic

References

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Guo T, Zhang D, Zeng Y, Huang TY, Xu H, Zhao Y. Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2020;15(1):40.

Lei P, Ayton S, Finkelstein DI, Spoerri L, Ciccotosto GD, Wright DK, et al. Tau deficiency induces parkinsonism with dementia by impairing APP-mediated iron export. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):291–5.

Lei P, Ayton S, Moon S, Zhang Q, Volitakis I, Finkelstein DI, et al. Motor and cognitive deficits in aged tau knockout mice in two background strains. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9(1):29.

Lei P, Ayton S, Appukuttan AT, Moon S, Duce JA, Volitakis I, et al. Lithium suppression of tau induces brain iron accumulation and neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(3):396–406.

Tuo QZ, Lei P, Jackman KA, Li XL, Xiong H, Li XL, et al. Tau-mediated iron export prevents ferroptotic damage after ischemic stroke. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(11):1520–30.

Shen LL, Manucat-Tan NB, Gao SH, Li WW, Zeng F, Zhu C, et al. The ProNGF/p75NTR pathway induces tau pathology and is a therapeutic target for FTLD-tau. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(8):1813–24.

Dage JL, Wennberg AMV, Airey DC, Hagen CE, Knopman DS, Machulda MM, et al. Levels of tau protein in plasma are associated with neurodegeneration and cognitive function in a population-based elderly cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(12):1226–34.

Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Smith R, Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Airey DC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid p-tau217 performs better than p-tau181 as a biomarker of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1683.

Barthélemy NR, Li Y, Joseph-Mathurin N, Gordon BA, Hassenstab J, Benzinger TLS, et al. A soluble phosphorylated tau signature links tau, amyloid and the evolution of stages of dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):398–407.

Karikari TK, Emeršič A, Vrillon A, Lantero-Rodriguez J, Ashton NJ, Kramberger MG, et al. Head-to-head comparison of clinical performance of CSF phospho-tau T181 and T217 biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12236.

Meng J, Lei P. Plasma pTau181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. MedComm. 2020;1(1):74–6.

Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, Howes SC, Fournier DR, Song L, et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(6):595–9.

Hong CY, Wu CC, Chiu YC, Yang SY, Horng HE, Yang HC. Magnetic susceptibility reduction method for magnetically labeled immunoassay. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;88(21):62.

Rubenstein R, Chang B, Davies P, Wagner AK, Robertson CS, Wang KK. A novel, ultrasensitive assay for tau: potential for assessing traumatic brain injury in tissues and biofluids. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(5):342–52.

Zu YB, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence. 66. The role of direct coreactant oxidation in the ruthenium tris (2,2 ')bipyridyl/tripropylamine system and the effect of halide ions on the emission intensity. Anal Chem. 2000;72(14):3223–32.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. In: 3rd Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics: July 3-5 2000. Oxford; 2000.

van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2002;21(4):589–624.

Harbord RM, Whiting P. Metandi: meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy using hierarchical logistic regression. Stata J. 2009;9(2):211–29.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Sterne JA. Meta-analysis in Stata: an updated collection from the Stata journal. StataCorp LP; 2009.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Shahim P, Tegner Y, Wilson DH, Randall J, Skillback T, Pazooki D, et al. Blood biomarkers for brain injury in concussed professional ice hockey players. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(6):684–92.

Bogoslovsky T, Wilson D, Chen Y, Hanlon D, Gill J, Jeromin A, et al. Increases of plasma levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein, tau, and amyloid beta up to 90 days after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(1):66–73.

Olivera A, Lejbman N, Jeromin A, French LM, Kim HS, Cashion A, et al. Peripheral total tau in military personnel who sustain traumatic brain injuries during deployment. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(10):1109–16.

Oliver JM, Jones MT, Anzalone AJ, Kirk KM, Gable DA, Repshas JT, et al. A season of American football is not associated with changes in plasma tau. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(23):3295–300.

Alosco ML, Tripodis Y, Jarnagin J, Baugh CM, Martin B, Chaisson CE, et al. Repetitive head impact exposure and later-life plasma total tau in former National Football League players. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;7:33–40.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Wennberg AMV, Airey DC, Savica R, Knopman DS, et al. Association of plasma total tau level with cognitive decline and risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in the Mayo Clinic study on aging. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(9):1073–80.

Muller S, Preische O, Gopfert JC, Yanez VAC, Joos TO, Boecker H, et al. Tau plasma levels in subjective cognitive decline: results from the DELCODE study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9529.

Kasai T, Tatebe H, Kondo M, Ishii R, Ohmichi T, Yeung WTE, et al. Increased levels of plasma total tau in adult Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188802.

Foiani MS, Woollacott IO, Heller C, Bocchetta M, Heslegrave A, Dick KM, et al. Plasma tau is increased in frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(8):804–7.

Bergman L, Zetterberg H, Kaihola H, Hagberg H, Blennow K, Akerud H. Blood-based cerebral biomarkers in preeclampsia: plasma concentrations of NfL, tau, S100B and NSE during pregnancy in women who later develop preeclampsia - a nested case control study. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196025.

Lippa SM, Yeh PH, Gill J, French LM, Brickell TA, Lange RT. Plasma tau and amyloid are not reliably related to injury characteristics, neuropsychological performance, or white matter integrity in service members with a history of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(14):2190–9.

Verberk IMW, Slot RE, Verfaillie SCJ, Heijst H, Prins ND, van Berckel BNM, et al. Plasma amyloid as prescreener for the earliest Alzheimer pathological changes. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(5):648–58.

Shahim P, Tegner Y, Marklund N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Neurofilament light and tau as blood biomarkers for sports-related concussion. Neurology. 2018;90(20):e1780–8.

Wallace C, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, van Donkelaar P. No change in plasma tau and serum neurofilament light concentrations in adolescent athletes following sport-related concussion. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206466.

Motamedi V, Kanefsky R, Matsangas P, Mithani S, Jeromin A, Brock MS, et al. Elevated tau and interleukin-6 concentrations in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2018;43:71–6.

Fortea J, Carmona-Iragui M, Benejam B, Fernandez S, Videla L, Barroeta I, et al. Plasma and CSF biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in adults with Down syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(10):860–9.

Zeitlberger AM, Thomas-Black G, Garcia-Moreno H, Foiani M, Heslegrave AJ, Zetterberg H, et al. Plasma markers of neurodegeneration are raised in Friedreich's ataxia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:366.

Shi M, Kovac A, Korff A, Cook TJ, Ginghina C, Bullock KM, et al. CNS tau efflux via exosomes is likely increased in Parkinson's disease but not in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(11):1125–31.

Karikari TK, Benedet AL, Ashton NJ, Lantero Rodriguez J, Snellman A, Suarez-Calvet M, et al. Diagnostic performance and prediction of clinical progression of plasma phospho-tau181 in the Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(2):429–42.

Pase MP, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, Satizabal CL, Aparicio HJ, DeCarli C, et al. Assessment of plasma total tau level as a predictive biomarker for dementia and related endophenotypes. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):598.

Korley FK, Yue JK, Wilson DH, Hrusovsky K, Diaz-Arrastia R, Ferguson AR, et al. Performance evaluation of a multiplex assay for simultaneous detection of four clinically relevant traumatic brain injury biomarkers. J Neurotrauma. 2018;36(1):182–7.

Kritikos M, Clouston SAP, Diminich ED, Deri Y, Yang X, Carr M, et al. Pathway analysis for plasma β-amyloid, tau and neurofilament light (ATN) in world trade center responders at midlife. Neurol Ther. 2020;9(1):159–71.

de Wolf F, Ghanbari M, Licher S, McRae-McKee K, Gras L, Weverling GJ, et al. Plasma tau, neurofilament light chain and amyloid-β levels and risk of dementia; a population-based cohort study. Brain. 2020;143(4):1220–32.

Verberk IMW, Hendriksen HMA, van Harten AC, Wesselman LMP, Verfaillie SCJ, van den Bosch KA, et al. Plasma amyloid is associated with the rate of cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly: the SCIENCe project. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;89:99–107.

Pattinson CL, Gill JM, Lippa SM, Brickell TA, French LM, Lange RT. Concurrent mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with elevated tau concentrations in peripheral blood plasma. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(4):546–54.

Romero JR, Demissie S, Beiser A, Himali JJ, DeCarli C, Levy D, et al. Relation of plasma β-amyloid, clusterin, and tau with cerebral microbleeds: Framingham heart study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(7):1083–91.

Petersen ME, Rafii MS, Zhang F, Hall J, Julovich D, Ances BM, et al. Plasma total-tau and neurofilament light chain as diagnostic biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults with Down syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;79(2):671–81.

Cantero JL, Atienza M, Ramos-Cejudo J, Fossati S, Wisniewski T, Osorio RS. Plasma tau predicts cerebral vulnerability in aging. Aging. 2020;12(21):21004–22.

Zetterberg H, Wilson D, Andreasson U, Minthon L, Blennow K, Randall J, et al. Plasma tau levels in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(2):9.

Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Janelidze S, Insel PS, Andreasson U, Stomrud EL, et al. Plasma tau in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1827–35.

Kovacs GG, Andreasson U, Liman V, Regelsberger G, Lutz MI, Danics K, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid tau and neurofilament concentrations in rapidly progressive neurological syndromes: a neuropathology-based cohort. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(11):1326–e77.

Deters KD, Risacher SL, Kim S, Nho K, West JD, Blennow K, et al. Plasma tau association with brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(4):1245–54.

Chen J, Yu JT, Wojta K, Wang HF, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies MAPT locus influencing human plasma tau levels. Neurology. 2017;88(7):669–76.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Xu J, Chai X, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, et al. Plasma phospho-tau181 increases with Alzheimer's disease clinical severity and is associated with tau- and amyloid-positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(8):989–97.

Park JC, Han SH, Yi D, Byun MS, Lee JH, Jang S, et al. Plasma tau/amyloid-beta1-42 ratio predicts brain tau deposition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2019;142(3):771–86.

Li WW, Shen YY, Tian DY, Bu XL, Zeng F, Liu YH, et al. Brain amyloid-beta deposition and blood biomarkers in patients with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69(1):169–78.

Startin CM, Ashton NJ, Hamburg S, Hithersay R, Wiseman FK, Mok KY, et al. Plasma biomarkers for amyloid, tau, and cytokines in Down syndrome and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):26.

Sugarman MA, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Tripodis Y, McKee AC, Stein TD, et al. A longitudinal examination of plasma neurofilament light and total tau for the clinical detection and monitoring of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;94:60–70.

Fossati S, Ramos Cejudo J, Debure L, Pirraglia E, Sone JY, Li Y, et al. Plasma tau complements CSF tau and P-tau in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2019;11:483–92.

Deniz K, Ho CCG, Malphrus KG, Reddy JS, Nguyen T, Carnwath TP, et al. Plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease in African Americans. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;79(1):323–34.

Lin CH, Yang SY, Horng HE, Yang CC, Chieh JJ, Chen HH, et al. Plasma biomarkers differentiate Parkinson's disease from atypical parkinsonism syndromes. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:123.

Chi NF, Chao SP, Huang LK, Chan L, Chen YR, Chiou HY, et al. Plasma amyloid beta and tau levels are predictors of post-stroke cognitive impairment: a longitudinal study. Front Neurol. 2019;10:715.

Chen TB, Lee YJ, Lin SY, Chen JP, Hu CJ, Wang PN, et al. Plasma Aβ42 and total tau predict cognitive decline in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13984.

Chen NC, Chen HL, Li SH, Chang YH, Chen MH, Tsai NW, et al. Plasma levels of α-synuclein, Aβ-40 and T-tau as biomarkers to predict cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:112.

Fang WQ, Hwu WL, Chien YH, Yang SY, Chieh JJ, Chang LM, et al. Composite scores of plasma tau and β-amyloids correlate with dementia in Down syndrome. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(2):191–6.

Chiu MJ, Fan LY, Chen TF, Chen YF, Chieh JJ, Horng HE. Plasma tau levels in cognitively normal middle-aged and older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:51.

Chiu MJ, Chen YF, Chen TF, Yang SY, Yang FP, Tseng TW, et al. Plasma tau as a window to the brain-negative associations with brain volume and memory function in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(7):3132–42.

Tzen KY, Yang SY, Chen TF, Cheng TW, Horng HE, Wen HP, et al. Plasma Abeta but not tau is related to brain PiB retention in early Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(9):830–6.

Yang SY, Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Lin CH, Jeng JS, Tang SC, et al. Analytical performance of reagent for assaying tau protein in human plasma and feasibility study screening neurodegenerative diseases. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9304.

Lee NC, Yang SY, Chieh JJ, Huang PT, Chang LM, Chiu YN, et al. Blood beta-amyloid and tau in Down syndrome: a comparison with Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:316.

Lue LF, Sabbagh MN, Chiu MJ, Jing N, Snyder NL, Schmitz C, et al. Plasma levels of Aβ42 and tau identified probable Alzheimer’s dementia: findings in two cohorts. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:226.

Yang CC, Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Chang HL, Liu BH, Yang SY. Assay of plasma phosphorylated tau protein (threonine 181) and total tau protein in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61(4):1323–32.

Chiu MJ, Lue LF, Sabbagh MN, Chen TF, Chen HH, Yang SY. Long-term storage effects on stability of Abeta1-40, Abeta1-42, and total tau proteins in human plasma samples measured with immunomagnetic reduction assays. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2019;9(1):77–86.

Jiao F, Yi F, Wang Y, Zhang S, Guo Y, Du W, et al. The validation of multifactor model of plasma Aβ (42) and total-tau in combination with MoCA for diagnosing probable Alzheimer disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:212.

Liu HC, Chiu MJ, Lin CH, Yang SY. Stability of plasma amyloid-β 1-40, amyloid-β 1-42, and total tau protein over repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2020;10(1):46–55.

Rubenstein R, Chang B, Yue JK, Chiu A, Winkler EA, Puccio AM, et al. Comparing plasma phospho tau, total tau, and phospho tau-total tau ratio as acute and chronic traumatic brain injury biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(9):1063–72.

Gardner RC, Rubenstein R, Wang KKW, Korley FK, Yue JK, Yuh EL, et al. Age-related differences in diagnostic accuracy of plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein and tau for identifying acute intracranial trauma on computed tomography: a TRACK-TBI study. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(20):2341–50.

Suárez-Calvet M, Karikari TK, Ashton NJ, Lantero Rodríguez J, Milà-Alomà M, Gispert JD, et al. Novel tau biomarkers phosphorylated at T181, T217 or T231 rise in the initial stages of the preclinical Alzheimer's continuum when only subtle changes in Aβ pathology are detected. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(12):e12921.

Moscoso A, Grothe MJ, Ashton NJ, Karikari TK, Lantero Rodríguez J, Snellman A, et al. Longitudinal associations of blood phosphorylated Tau181 and neurofilament light chain with neurodegeneration in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4986.

O'Connor A, Karikari TK, Poole T, Ashton NJ, Lantero Rodriguez J, Khatun A, et al. Plasma phospho-tau181 in presymptomatic and symptomatic familial Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0838-x.

Lantero Rodriguez J, Karikari TK, Suárez-Calvet M, Troakes C, King A, Emersic A, et al. Plasma p-tau181 accurately predicts Alzheimer's disease pathology at least 8 years prior to post-mortem and improves the clinical characterisation of cognitive decline. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(3):267–78.

Karikari TK, Pascoal TA, Ashton NJ, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, Rodriguez JL, et al. Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):422–33.

Thijssen EH, La Joie R, Wolf A, Strom A, Wang P, Iaccarino L, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):387–97.

Janelidze S, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, Smith R, Beach TG, Serrano GE, et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer's dementia. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):379–86.

Kitaguchi N, Tatebe H, Sakai K, Kawaguchi K, Matsunaga S, Kitajima T, et al. Influx of tau and amyloid-beta proteins into the blood during hemodialysis as a therapeutic extracorporeal blood amyloid-beta removal system for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69(3):687–707.

Oliver JM, Anzalone AJ, Stone JD, Turner SM, Blueitt D, Garrison JC, et al. Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. 2019;130(5):1655–62.

Shi Y, Lu X, Zhang L, Shu H, Gu L, Wang Z, et al. Potential value of plasma amyloid-beta, total tau, and neurofilament light for identification of early Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(8):3479–85.

Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589–99.

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Öhrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673–84.

Wang HY, Bakshi K, Frankfurt M, Stucky A, Goberdhan M, Shah SM, et al. Reducing amyloid-related Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis by a small molecule targeting filamin a. J Neurosci. 2012;32(29):9773–84.

Tatebe H, Kasai T, Ohmichi T, Kishi Y, Kakeya T, Waragai M, et al. Quantification of plasma phosphorylated tau to use as a biomarker for brain Alzheimer pathology: pilot case-control studies including patients with Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):63.

Benussi A, Karikari TK, Ashton N, Gazzina S, Premi E, Benussi L, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serum NfL and p-tau (181) in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(9):960–7.

Shekhar S, Kumar R, Rai N, Kumar V, Singh K, Upadhyay AD, et al. Estimation of tau and phosphorylated Tau181 in serum of Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159099.

Moscoso A, Grothe MJ, Ashton NJ, Karikari TK, Rodriguez JL, Snellman A, et al. Time course of phosphorylated-tau181 in blood across the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Brain. 2021;144(1):325–39.

Zettergren A, Lord J, Ashton NJ, Benedet AL, Karikari TK, Lantero Rodriguez J, et al. Association between polygenic risk score of Alzheimer's disease and plasma phosphorylated tau in individuals from the Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):17.

Simrén J, Leuzy A, Karikari TK, Hye A, Benedet AL, Lantero-Rodriguez J, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12283.

Keshavan A, Pannee J, Karikari TK, Rodriguez JL, Ashton NJ, Nicholas JM, et al. Population-based blood screening for preclinical Alzheimer's disease in a British birth cohort at age 70. Brain. 2021:awaa403. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa403.

Palmqvist S, Janelidze S, Quiroz YT, Zetterberg H, Lopera F, Stomrud E, et al. Discriminative accuracy of plasma phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer disease vs other neurodegenerative disorders. JAMA. 2020;324(8):772–81.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018YFC1312300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81722016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PL contributed to the conception, project design, and data interpretation. XLD and STZ performed literature research and drafted the manuscript. LW and LJJ helped to collect the data and performed statistical analyses. TL contributed to data interpretation. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ information

1 Department of Neurology and State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy/Collaborative Innovation Center for Biotherapy, National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; 2 Department of Neurology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; 3 Mental Health Center and West China Brain Research Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; 4 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional Files

Additional file 1 Table S1.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses. Table S2. Meta-regression results. Table S3. Summary of estimate values of diagnostic accuracy.

Additional file 2 Fig. S1.

Quality assessment results of included articles. Fig. S2. The levels of plasma tau and ptau181 in healthy people using Simoa in different subgroups. Fig. S3. The level of plasma tau in healthy people using IMR in different subgroups. Fig. S4. The levels of plasma tau and ptau181 in healthy people using EIMAF/a-EIMAF and MSD. Fig. S5. Comparison of plasma tau and ptau181 between AD and healthy controls using Simoa, IMR, and MSD. Fig. S6. Funnel plot of the random-effect analysis. Fig. S7. The diagnostic accuracy of plasma ptau181 using MSD.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, X., Zhang, S., Jiang, L. et al. Ultrasensitive assays for detection of plasma tau and phosphorylated tau 181 in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Neurodegener 10, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-021-00234-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-021-00234-5