Abstract

Background

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is a major clinical problem in tertiary hospitals in Tanzania and jeopardizes the life of neonates in critical care units (CCUs). To better understand methods for prevention of MDR infections, this study aimed to determine, among other factors, the role of MDR-Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) contaminating neonatal cots and hands of mothers as possible role in transmission of bacteremia at Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), Mwanza, Tanzania.

Methods

This cross-sectional, hospital-based study was conducted among neonates and their mothers in a neonatal intensive care unit and a neonatology unit at BMC from December 2018 to April 2019. Blood specimens (n = 200) were sub-cultured on 5% sheep blood agar (SBA) and MacConkey agar (MCA) plates. Other specimens (200 neonatal rectal swabs, 200 maternal hand swabs and 200 neonatal cot swabs) were directly inoculated on MCA plates supplemented with 2 μg/ml cefotaxime (MCA-C) for screening of GNB resistant to third generation cephalosporins, r-3GCs. Conventional biochemical tests, Kirby-Bauer technique and resistance to cefoxitin 30 μg were used for identification of bacteria, antibiotic susceptibility testing and detection of MDR-GNB and screening of potential Amp-C beta lactamase producing GNB, respectively.

Results

The prevalence of culture confirmed bacteremia was 34.5% of which 85.5% were GNB. Fifty-five (93.2%) of GNB isolated from neonatal blood specimens were r-3GCs. On the other hand; 43% of neonates were colonized with GNB r-3GCs, 32% of cots were contaminated with GNB r-3GCs and 18.5% of hands of neonates’ mothers were contaminated with GNB r-3GCs. The prevalences of MDR-GNB isolated from blood culture and GNB r-3GCs isolated from neonatal colonization, cots and mothers’ hands were 96.6, 100, 100 and 94.6%, respectively. Significantly, cyanosis (OR[95%CI]: 3.13[1.51–6.51], p = 0.002), jaundice (OR[95%CI]: 2.10[1.07–4.14], p = 0.031), number of invasive devices (OR[95%CI]: 2.52[1.08–5.85], p = 0.031) and contaminated cot (OR[95%CI]: 2.39[1.26–4.55], p = 0.008) were associated with bacteremia due to GNB. Use of tap water only (OR[95%CI]: 2.12[0.88–5.09], p = 0.040) was protective for bacteremia due to GNB.

Conclusion

High prevalence of MDR-GNB bacteremia and intestinal colonization, and MDR-GNB contaminating cots and mothers’ hands was observed. Improved cots decontamination strategies is crucial to limit the spread of MDR-GNB. Further, clinical presentations and water use should be considered in administration of empirical therapy whilst awaiting culture results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is defined as acquired resistance to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes [1,2,3]. MDR is a growing global concern which is estimated to cause 10 million deaths and cost US$100 trillion annually by 2050 [4, 5]. Improper use of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine, counterfeit antibiotics and non-compliant use of rationally prescribed antibiotics are among factors driving the emergence and spread of MDR bacteria [6]. High antibiotic pressure (empirically prescribed and administered) in the critical care units (intensive care units and neonatology units) results in the selection and emergence of MDR bacteria [7, 8]. The spread of MDR bacteria in healthcare settings presents a challenge, as treating infected patients becomes increasingly difficult with poorer outcomes [6]. MDR Gram-negative bacteria (MDR-GNB) such as beta-lactamase (extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), Amp-C beta-lactamase and carbapenemases) producing Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are frequently reported, causing infections in critical care units globally [9,10,11,12]. These organisms are responsible for bloodstream infections (BSIs), urinary tract infections (UTIs), pneumonia, and skin and soft tissue infections, resulting in high morbidity and mortality [13].

In critical care units, infections due to MDR-GNB bacteria may be acquired endogenously or exogenously [14]. Endogenous acquisition occurs from the patient’s own body flora colonizing a certain body surface, for example, MDR-GNB colonizing patient’s gastrointestinal tract (such as MDR-E. coli) may cause an extra-intestinal infection (e.g., BSI and UTI) which may even result to mortality from treatment failure [14, 15]. Exogenous acquisition occurs due to contact with other people e.g., healthcare workers (HCWs), patients or care givers (CGs) i.e., mothers; and/or contaminated surfaces, such as ventilators, beds, side tables and infusion stands, and water sources [14, 16]. Contaminated patients’ environments with MDR-GNB increases the risk of exogenous acquire of healthcare associate infections (HCAIs) from MDR-GNB which are mostly cross-transmitted by contaminated hands of HCWs and CGs [17]. Hands of HCWs and CGs become contaminated when touching contaminated surfaces and even colonized patients during provision of medical care [18].

In Mwanza, Tanzania, 10.5 to 49% of bacteremia cases due to GNB are caused by MDR-GNB with mortality rate ranging from 34.4 to 52% as compared to mortality with none MDR-GNB which ranging from 16.2 to 25% [11, 19, 20]. Rectal colonization of neonates with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) is common (25.4 to 54.6%) [19, 20], as is contamination of the hospital’s inanimate surfaces (33.5%) [21]. In Tanzania, it is common that, mothers play an important role in feeding and caring for hospitalized neonates. To date, their role in infection transmission or prevention has not been considered. To reduce the incidence and improve the management of MDR-GNB cases in the neonatal ICU and neonatology unit at BMC, we explored exogenous and endogenous risk factors for neonatal MDR-GNB sepsis, including potential exogenous exposures in the household of origin, in the hospital or from mothers, and endogenous exposure (neonatal carriage). Results can be used to inform case management, and to target infection prevention and control measures to reduce case incidence.

Methods

The aim, design and setting of the study

A cross-sectional hospital-based study was conducted between December 2018 and July 2019 aimed to determine, among other factors, the role of MDR-Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) contaminating neonatal cots and hands of mothers as possible role in transmission of bacteremia among neonates admitted to the neonatal ICU (NICU) and neonatology unit at Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC is a tertiary, teaching, consultancy and zonal referral hospital with an estimated 1000-bed capacity, serving Lake Zone regions (Mwanza, Simiyu, Kagera, Shinyanga, Musoma, Tabora, Geita and Kigoma) and a catchment population of 13 million people (https://www.bugandomedicalcentre.go.tz/index.php). The NICU was equipped with 15 neonatal cots (with no walking space between cots), 15 trained nurses and 2 pediatricians. In the neonatology unit, there were 36 cots about 0.5 m apart, 11 trained nurses and 4 pediatricians. When operating at or above capacity, two neonates may share a cot (in both units). In both units, the cots are irregularly disinfected before new occupancy by using 1:50 Dettol in water.

Sample size calculation and selection criteria

A minimum sample size for this study was 144 participants, which was calculated using Kish Leslie formula of 1965 [22], using an MDR-GNB prevalence of 10.5% [20]. Neonates admitted to NICU and neonatology unit with signs and symptoms of infections as previous reported by “WHO Young infants Study group” [23] and their mothers were enrolled in this study. Neonates with signs and symptoms of infection but either missing socio-demographic information or a complete set of specimens were excluded from the final analysis (n = 15). Participants (neonates and mothers) moving between the neonatal ICU and neonatology units were not re-enrolled.

Data and specimen collection

Structured questionnaires were used to obtain socio-demographic and clinical information from study participants after the mother or guardian consented to participation. Neonatal blood samples, neonatal rectal swabs, cot swabs and maternal hand swabs were collected. About 1 ml of venous blood was collected into an in-house made tryptone soy broth (TSB, 10 ml) by paediatrician; rectal swabs were collected by a trained medical doctor; and bed swabs (in every new occupancy) and mothers’ hand swabs specimens were collected. All swab samples were collected using sterile cotton swabs pre-moistened in sterile 0.85% physiological saline. All swab specimens were transported to the laboratory in Amies transport media (Amies, UK). In total, 800 specimens (200 blood, 200 rectal swabs, 200 bed swabs and 200 mothers’ hands swabs) were collected. All specimens were sent to the microbiology laboratory of the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences for isolation, identification, antibiotic susceptibility testing and detection of MDR-GNB following in-house standard operating procedures and international guidelines such as Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI, 2018) [24].

Definitions

In this study, GNB isolated from blood with resistance to ceftriaxone and/or ceftazidime and GNB isolated from rectal, bed and hand swabs grown on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with 2 μg/ml cefotaxime (MCA-C) were considered resistant to third generation cephalosporins (r-3GCs) [11]. All GNB isolated from neonates’ blood, rectal, cots and mothers’ hands swab specimens showing resistance to at least one antibiotic agent in three different classes of antibiotics i.e., penicillins: ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin/clavulanate (AMC), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP); third generation cephalosporins (3GCs): ceftriaxone (CRO), ceftazidime (CAZ) and/or isolated on MCA-C; carbapenems: meropenem (MEM); trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT); aminoglycosides: gentamicin (CN), amikacin (AK); fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin (CIP); tetracyclines: tetracycline (TET); and /or polymyxins: colistin (CT), were termed as MDR-GNB as previously reported [1, 2]. In this paper, isolates exhibiting intermediate activities against antibiotics were also termed as resistant.

Laboratory procedures

Bacterial isolation, identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing

Clinical specimens (blood): Blood specimens in TSB bottles were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18–24 h upon receipt in the laboratory, and before being inoculated onto in-house prepared 5% sheep blood agar (SBA) and MacConkey agar (MCA) plates (Oxoid, UK). SBA and MCA plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18–24 h. However isolation of Gram positive bacteria was not the objective of this study, we purposely isolated and identified them and their antibiotic susceptibility testing were performed to guide rational antibiotic therapy for proper patients’ management only.

Isolated bacteria were identified by in-house prepared conventional biochemical identification tests including sugars fermentation, CO2 gas production and sulfur production by triple sugar iron (TSI) test; sulfur production, indole production and motility by sulfur-indole-motility (SIM) test, urease production by urease test; utilization of citrate as the sole source of energy by Simmons’ citrate test; and oxidase production by oxidase test strips as reported previously [25]. Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method was used for antibiotics susceptibility testing (AST) on MHA plates [26]. Briefly, bacterial suspensions equivalent to 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard solution were prepared from a MacConkey subculture (arising from a cultured clinical specimen and one isolated colony from cefotaxime-supplemented MacConkey agar) into sterile 0.85% physiological saline and then swabbed on entire plates of MHA (Oxoid, UK). Ampicillin (AMP) 10 μg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) 25 μg, amikacin (AK) 30 μg, tetracycline (TE) 30 μg, piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) 110 μg, gentamicin (CN) 10 μg, ciprofloxacin (CIP) 5 μg, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC) 30 μg, ceftriaxone (CRO) 30 μg, ceftazidime (CAZ) 30 μg, meropenem (MEM) 10 μg and colistin sulfate (CT) 10 μg antibiotic discs (Oxoid, UK) were seeded onto inoculated MHA plates within 15 min. Interpretation of zones of inhibitions was done according to CLSI, 2018 [27]. Cefoxitin (FOX) 30 μg discs were also included in AST purposely for screening of potential Amp-C beta lactamase producing GNB. Isolates exhibiting zone diameters ≤18 mm were considered potential Amp-C beta lactamase producers as reported previous [28, 29]. Zone diameters for CT were interpreted as previous reported by Galani et al. 2008 [30].

Colonization and contamination specimens (rectal, cot and hand swabs): Immediately upon receipt of swab specimens in the laboratory, these were inoculated on MCA-C (Medochemie Ltd., Cyprus) for isolation of MDR-GNB. Plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18–24 h. Conventional biochemical identification tests were used for characterisation of isolates to species levels as described earlier. For AST, the antimicrobial panels and concentrations were as described above, but beta-lactam antibiotic discs were excluded as isolation of resistant GNB involved the use of cefotaxime (beta-lactam) 2 μg/ml supplemented MCA plates. CLSI (2018) [27] and Galani et al. 2008 [30] guidelines were used for interpretation of zones of inhibitions.

Statistical analysis

STATA software version 13.0 was used for data analysis. Continuous data were presented as median (interquartile range) whereby categorical data were presented as percentages and fractions. Logistic regression and a stepwise backwards model selection analysis was used to determine risk factors and clinical symptoms for neonatal bacteremia in critical care units. A p value less than 0.05 at 95% confidence interval was considered statistical significant.

Results

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of neonates admitted in neonatal ICU and neonatology unit at BMC

Two-hundred neonates with median age (interquartile range) of 1 (1–2) days were enrolled during this study period, including 52.5% males and 47.5% females. Just over half of the neonates (58%) were enrolled from the neonatology unit. The median duration (interquartile range) of a hospital stay was 7 (1–22.5) days. The majority of neonates (73%), were enrolled after > 48 h of admission and 87.5% were on antibiotic treatment at the time of clinical sampling and 24.5 and 84% had fever and invasive devices during enrolment, respectively. In-unit mortality was 9% in either unit (Table 1).

Culture results; blood, rectal, neonatal cots and mothers’ hands specimens

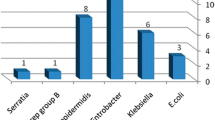

The prevalence of culture confirmed bacteremia was 34.5% of which 85.5% were GNB. About 93.2% of the GNB isolated from positive blood cultures were r-3GCs. The prevalence of GNB r-3GCs (grown MCA-C) colonizing neonates, contaminating neonates’ cots and mothers’ hands was 43, 32 and 18.5%, respectively. K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter spp., E. coli and C. freundii were frequently isolated from neonates’ blood and rectal swab specimens suggesting that rectal colonization may be the source of bacteremia. On the other hand, K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter spp. and E. aerogenes were frequently isolated from neonates’ cots and mothers’ hands suggesting possibilities of mothers’ hands get contaminated when touching contaminated neonates’ cots. The incidence of potential Amp-C beta lactamase producers was higher among isolates contaminating neonates’ cots and mothers’ hands, respectively (Table 2).

Percentage resistance of GNB isolated from blood culture and GNB r-3GCs isolated from rectal, cots and hands swabs specimens and respective magnitude of MDR-GNB

More than 90% of GNB isolated from blood exhibited resistance to AMP, SXT, AMC and CRO. Isolates colonizing neonates and contaminating their cots had similar frequencies of antibiotics resistance. Both exhibited more than 95 and 70% resistance to STX and TE, respectively. GNB contaminating mothers’ hands were highly resistant to SXT (> 90%) and CN (> 85%). GNB contaminating cots were more resistant to CT (67.2%) compared to GNB isolated from blood (47.5%), rectal swabs (52.6%) and mothers’ hand swabs (40.5%). Comparison of common antibiotic agents tested against all isolates is reported below in Fig. 1. Over 90% of GNB isolated from blood, rectal swabs, neonates’ cots and hands of neonates’ mothers were MDR-GNB (resistant to one or more antibiotic agents in three different classes of antibiotics), Fig. 2.

Factors associated with bacteremia in critical care units

On multivariate regression analysis, cyanosis (OR[95%CI]: 3.13[1.51–6.51], p = 0.002), jaundice (OR[95%CI]: 2.10[1.07–4.14], p = 0.031), number of invasive devices (OR[95%CI]: 2.52[1.08–5.85], p = 0.031), maternal fever during pregnancy (OR[95%CI]: 2.17[1.17-4.05], p = 0.014) and contaminated cot with MDR-GNB (OR[95%CI]: 2.39[1.26–4.55], p = 0.008) found to be significantly associated with bacteremia due to GNB. The use of tap water only (OR[95%CI]: 2.12[0.88–5.09], p = 0.040) was protective for bacteremia due to GNB (Table 3). In addition, neonates colonized with MDR-GNB, their cots were also significantly contaminated with MDR-GNB (OR[95%CI]: 2.43[1.33–4.47], p = 0.004).

Phenotypic similarities of MDR-GNB between blood isolates and rectal colonization or bed contamination or mother’s hand contamination

A proportion of 11.7% (7/59), 8.5% (5/59) and 6.8% (4/59) MDR-GNB isolates causing bacteremia had identical bacteria species with MDR-GNB colonizing neonates, contaminating neonates’ beds and contaminating hands of neonates’ mothers, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Slightly majority (52.5%) of neonates enrolled in this study were males with overall median duration of stay in the respective unit of 7 days however 1 day was the shortest stay and about 23 days was the longest stay. The majority (73%) were enrolled in this study after 48 h of being admitted in the respective unit, suggesting that these neonates developed HCAIs however this was not statistically significant. The majority (87.5%) of neonates were also on antibiotics use during clinical sampling, which may have reduced the sensitivity of culture based diagnostic tests mainly blood culture [31, 32].

In the current study, about one third of neonates had positive culture confirmed bacteremia, despite the fact that a large proportion of neonates were already receiving treatment, which may reduce recover of bacteria from blood culture [31, 32]. Over three quarters of the isolated bacteria from blood cultures were Gram-negative bacteria, of which K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter spp. and E. coli were frequently isolated. Similar results were reported previously in the same setting, BMC [11] and elsewhere [33].

Significantly large proportion of GNB isolated from blood culture were resistant to 3GCs. In addition, almost 95% of GNB isolated from blood culture and GNB r-3GCs isolated from rectal, cots and mothers’ hands swabs were found to be MDR-GNB. Generally, all MDR-GNB isolated from blood, rectal swabs, bed swabs and hand swabs were more frequently resistant to commonly used antibiotics than uncommon antibiotics. Commonly used antibiotics, such as ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftriaxone, are used as first- and second-line treatment options and as prophylaxis [34]. The MDR-GNB showed low prevalences of resistance against amikacin and meropenem. Regulated use of these antibiotics in Tanzania, as meropenem is reserved for treatment of infections with MDR bacteria and amikacin for treatment of tuberculosis and actinemycetoma, may explain the low bacterial resistance against them [34]. Despite the fact that colistin sulfate is not registered and available for clinical use in Tanzania [34], GNB isolated in our settings exhibited higher percentages of resistance against it. In the same region (Tanzania), one study reported a 66.1% resistance to colistin sulfate among Enterobacteriaceae colonizing hotel employees [35] and another study reported a 95.6% resistance to colistin sulfate among Campylobacter spp. isolated from humans [36]. The use of colistin sulfate in veterinary medicine in Tanzania [37], suggests that, veterinary use of antimicrobials may be a key driver of the AMR problems in environment as well as clinical settings as observed in this study.

This current study examined risk factors of bacteremia due to GNB based on pre-admission history, neonatal clinical presentation and potential transmission in the unit; neonatal ICU and/or neonatology unit. Therefore, this study found that, domestic use of tap water only as pre-admission history is protective factor (p = 0.040) for bacteremia. Treatment of water for domestic use by sand filtrations at water treatment plant in Mwanza [38], may have been played an effective role of reducing the absolute concentrations of MDR-bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) from contaminated source [39] as reported by Zhang et al, 2016 [40]. Thus, admitted neonates with parents’ domestic use of water from open sources such as dams and lake, should be screened for possibilities of bacteremia due to GNB. Maternal fever during pregnancy is the manifestation of systemic inflammations which may be due to infections such as BSIs, UTIs, infections of the amniotic fluid, or foetal membranes or placenta. Apart from causing maternal complications, these infections may be associated with early onset of neonatal complications such as bacteremia, pneumonia and meningitis [54]. Neonates with clinical presentations of jaundice (p = 0.031) and cyanosis (p = 0.002) were significantly culture confirmed positive for bacteremia due to GNB. Sepsis induces host production of cytokines (interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species), which result in dysregulated systemic inflammatory response associated with multiple organ damage and shock e.g., cardiac dysfunction and hepatocellular injury [41]. Cardiac dysfunction, a cardiopulmonary condition, causes shortage supply of oxygenated haemoglobin (blood) reaching body parts resulting to cyanosis [42]. Further, hepatocellular injury and bacterial products which causes hemolysis e.g., cytolysins, promotes elevation of serum bilirubin leading to jaundice [43]. Therefore, cyanosis and jaundice can be used as accompanying markers in diagnosis of sepsis among neonates in critical care units. Empirical antibiotic therapy, may also be initiated after blood sample collection if neonate presents clinical signs and symptoms of cyanosis and jaundice and whilst awaiting for microbiological culture results. However, third line antibiotic therapy is recommended at this setting as significant higher proportion of GNB isolated from blood culture are resistant to 3GCs and are MDR-GNB, respectively.

Contaminated cots (p = 0.008) and multiple invasive devices (p = 0.031) suggests potential transmission in the units as they significantly associated with bacteremia. Similar findings were reported elsewhere [44,45,46]. Invasive devices e.g., intravascular lines required for venous access for administration of medications among critically ill may also provide portal of entry of potential pathogenic bacteria if inserted through contaminated skin [45]. Contaminated inanimate surfaces in the patient’s zone (patient’s immediate surroundings) such as cots increases the risk of healthcare associated infections (HCAIs) mostly among patients with multiple invasive devices [46]. Contaminated hands of HCWs and/or CGs play the major role in cross-transmitting pathogens from contaminated inanimate surfaces to patients resulting to HCAIs [46].

As previously reported [20], rectal colonization with MDR-GNB among neonates in critical care units is high at BMC. This study (43%) and a another study (54.6%) in 2016 [20] found a higher prevalence of neonatal rectal colonization with MDR-GNB than a study (25.4%) conducted in 2013 [19] at BMC. Trends towards increasing prevalence of MDR colonization likely reflect increasing rates of antibiotic resistance. A study conducted from 2013 to 2015 [47] observed high resistance of GNB to 3GCs causing infections at the same setting, Mwanza, Tanzania. Similarly to other studies [19, 48, 49], MDR-K. pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. were the most common GNB r-3GCs and potential Amp-C beta-lactamase producers, respectively, predominantly colonizing neonates in critical care units in our study.

A large proportion (32%) of neonates’ cots were contaminated with MDR-GNB, significantly (p = 0.004) associated with rectal colonization of the current neonates occupying the cots. Similar observation, large proportion of inanimate surfaces contamination, was reported previous in similar hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania [21]. The capacity for biofilm formation and multiple mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics, heavy metals and detergents/disinfectants enables long duration survival of contaminating bacteria on inanimate surfaces including cots [46, 50, 51]. Patients’ immediate inanimate surfaces, such as neonatal cots, can be directly contaminated by microorganisms shedded from infected and/or colonized patients as observed in this study that, contamination of neonatal cots is significantly associated with neonate’s rectal colonization. Microorganisms, may also be cross-transmitted to contaminate inanimate surfaces through contaminated hands of healthcare workers (HCWs) and caregivers (CGs) [46]. Overcrowding of neonates, unacceptably small distances between cots and infrequent decontamination of neonates’ cots as observed by this study may lead to increased contamination of neonates’ cots in this settings. Furthermore, other factors including concentration of decontaminant, types of surface contaminating bacteria, contact time with surfaces, and care of cleaning cloth are reported associated with high levels of contamination of inanimate surfaces [39]. CDC recommends regularly decontamination of reusable cleaning cloths and mops [40]. Further, surfaces contaminated with MDR-GNB were found a significant risk factor for bacteremia in critical care units as reported previously [52]. A patient occupying a bed or room after an MDR colonized or infected patient, which was improperly (or not) disinfected, has an increased risk of acquiring infection due to MDR bacteria [52].

Almost one fifth (18.5%) of mothers’ hands were contaminated with GNB r-3GCs in this setting. High proportion (94.6%) of GNB -3GCs, were MDR-GNB. Before touching and breastfeeding their neonates, mothers wash their hands with running tap water and detergents. It is possible that handwashing practices are insufficient or they acquired contamination when touching contaminated surfaces such as beds and/or during other contact with their baby such as diaper changing, as significant number of neonates and beds were colonized and contaminated, respectively. The hands of healthcare workers (HCWs) or caregivers (CGs) after touching contaminated inanimate surfaces such as beds act as vehicles in cross-transmitting MDR bacteria to patients [53]; consequently resulting to patients’ acquisition of infections due to MDR bacteria.

This study observed seven, five and four pairs out of 59 pairs of MDR-GNB isolated from neonatal blood having similar species with MDR-GNB isolated from rectal colonization, cots contamination and mothers’ hands contamination, respectively. This observation may suggests possible cross-transmission of MDR-GNB between these niches [46]. Further, screening of multiple isolates per sample and molecular typing techniques with greater resolution, e.g. multi-locus sequence typing, pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or, ideally, whole genome sequencing (WGS) will be important in determining clonal similarities of these isolates.

Conclusion

Our study found high prevalence of antimicrobial resistant Gram-negative bacteria in sepsis patients in neonatal ICU and neonatology unit. Additionally, high prevalence of MDR-GNB colonizing neonates, contaminating hands of neonates’ mothers and contaminating neonates’ immediate environment, their cots, is extremely concerning. As a result, this study provides evidence for immediate recommendation for: better and frequently (e.g., weekly) decontamination on neonates’ cots; information campaign for mothers on potential cross-transmission of MDR bacteria in causing bacteremia through contaminated hands; and prioritization of 3rd line treatments based on clinical (cyanosis and jaundice) and pre-admission history (domestic use of open water sources) in neonatal intensive care and neonatology units at this setting. Furthermore, a follow-up study is recommended to determine the incidence of bacteremia after proper decontamination protocols are followed up and mothers are educated on infection control practices as recommended.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Microbiology Laboratory Department at Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Bugando, Mwanza-Tanzania.

Abbreviations

- AMC:

-

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid

- AMP:

-

Ampicillin

- ARGs:

-

Antibiotic resistant genes

- AST:

-

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

- BMC:

-

Bugando Medical Centre

- CAZ:

-

Ceftazidime

- CG:

-

Care giver

- CIP:

-

Ciprofloxacin

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CN:

-

Gentamicin

- CRO:

-

Ceftriaxone

- CT:

-

Colistin sulfate

- DDS:

-

Double Disk Synergy

- GNB:

-

Gram-negative bacteria

- HCAIs:

-

Healthcare associated infections

- HCW:

-

Health care worker

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPC:

-

Infection prevention and control

- MCA-C:

-

MacConkey Agar supplemented with cefotaxime

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistance

- NICU:

-

Neonatal ICU

- r-3GCs:

-

resistant to third generation cephalosporins

- SBA:

-

Sheep blood agar

- TSI:

-

Triple sugar iron

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- 3GC:

-

Third generation cephalosporin

References

Basak S, Singh P, Rajurkar M. Multidrug resistant and extensively drug resistant bacteria: a study. Journal of pathogens. 2016;2016:1–5.

Sweeney MT, Lubbers BV, Schwarz S, Watts JL. Applying definitions for multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance and pandrug resistance to clinically significant livestock and companion animal bacterial pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(6):1460–3.

Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(1):1–14.

OBI J, Berthe A, Jean FC, Le Gall FG, Marquez PV. Drug-resistant infections : a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2) : final report (English). In: HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative. Washington, D.C: The World Bank; 2017.

O’neill J. Review on antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. 2014. London: HM Government; 2016.

Ndihokubwayo JB, Yahaya AA, Desta AT, Ki-Zerbo G, Odei E, Keita B, Pana AP, Nkhoma W. Antimicrobial resistance in the African region: issues, challenges and actions proposed. African Health Monitor. 2013;16:27–30.

Albrich W, Angstwurm M, Bader L, Gärtner R. Drug resistance in intensive care units. Infection. 1999;27(2):S19–23.

Karam G, Chastre J, Wilcox MH, Vincent J-L. Antibiotic strategies in the era of multidrug resistance. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):136.

Vincent J-L, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, Moreno R, Lipman J, Gomersall C, Sakr Y. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. Jama. 2009;302(21):2323–9.

Tosi M, Roat E, De Biasi S, Munari E, Venturelli S, Coloretti I, Biagioni E, Cossarizza A, Girardis M. Multidrug resistant bacteria in critically ill patients: a step further antibiotic therapy. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2018;2:1–9.

Kayange N, Kamugisha E, Mwizamholya DL, Jeremiah S, Mshana SE. Predictors of positive blood culture and deaths among neonates with suspected neonatal sepsis in a tertiary hospital, Mwanza-Tanzania. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10(1):39.

Choudhuri AH, Khurana P, Biswas PS, Uppal R. Epidemiology and risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria in critically ill patients with liver disease. Saudi J Anaesth. 2018;12(3):389.

WHO: WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. 2017.

WHO. Prevention of hospital-acquired infections : a practical guide. In: JFaLN GD, editor. . 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Seni J. Characterization of Escherichia coli involved in extraintestinal infections among patients in North-Western Tanzania: circulating sequence types, risk factors and antimicrobial resistance profiles; 2018.

Choi WS, Kim SH, Jeon EG, Son MH, Yoon YK, Kim J-Y, Kim MJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Park DW. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care units and successful outbreak control program. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(7):999–1004.

La Fauci V, Costa GB, Genovese C, Palamara MAR, Alessi V, Squeri R. Drug-resistant bacteria on hands of healthcare workers and in the patient area: an environmental survey in southern Italy’s hospital. Revista Española de Quimioterapia. 2019;32(4):303.

Morgan DJ, Rogawski E, Thom KA, Johnson JK, Perencevich EN, Shardell M, Leekha S, Harris AD. Transfer of multidrug-resistant bacteria to healthcare workers’ gloves and gowns after patient contact increases with environmental contamination. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1045.

Nelson E, Kayega J, Seni J, Mushi MF, Kidenya BR, Hokororo A, Zuechner A, Kihunrwa A, Mshana SE. Evaluation of existence and transmission of extended spectrum beta lactamase producing bacteria from post-delivery women to neonates at Bugando medical center, Mwanza-Tanzania. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):279.

Marando R, Seni J, Mirambo MM, Falgenhauer L, Moremi N, Mushi MF, Kayange N, Manyama F, Imirzalioglu C, Chakraborty T. Predictors of the extended-spectrum-beta lactamases producing Enterobacteriaceae neonatal sepsis at a tertiary hospital, Tanzania. Int J Med Microbiol. 2018;308(7):803–11.

Moremi N, Claus H, Silago V, Kabage P, Abednego R, Matee M, Vogel U, Mshana S. Hospital surface contamination with antimicrobial-resistant gram-negative organisms in Tanzanian regional and tertiary hospitals: the need to improve environmental cleaning. J Hosp Infect. 2019;102(1):98–100.

Kish L. Survey sampling; 1965.

Group WYIS. Clinical prediction of serious bacterial infections in young infants in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(10):S23–31.

In C. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In: Wayne PA, editor. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018.

Winn WC. Koneman's color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology: Lippincott Williams & wilkins; 2006.

Bauer A, Kirby W, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45(4_ts):493–6.

CLSI: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 28th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wyne, PA. Pennsylvania: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018. 2018.

Jacoby GA. AmpC β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(1):161–82.

Polsfuss S, Bloemberg GV, Giger J, Meyer V, Böttger EC, Hombach M. Practical approach for reliable detection of AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(8):2798–803.

Galani I, Kontopidou F, Souli M, Rekatsina P-D, Koratzanis E, Deliolanis J, Giamarellou H. Colistin susceptibility testing by Etest and disk diffusion methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(5):434–9.

Harris AM, Bramley AM, Jain S, Arnold SR, Ampofo K, Self WH, Williams DJ, Anderson EJ, Grijalva CG, McCullers JA. Influence of antibiotics on the detection of bacteria by culture-based and culture-independent diagnostic tests in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. In: Open forum infectious diseases: Oxford University Press; 2017, 2017.

Mubito EP, Shahada F, Kimanya ME, Buza JJ. Antimicrobial use in the poultry industry in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania and public health implications; 2014.

Breurec S, Bouchiat C, Sire J-M, Moquet O, Bercion R, Cisse MF, Glaser P, Ndiaye O, Ka S, Salord H. High third-generation cephalosporin resistant Enterobacteriaceae prevalence rate among neonatal infections in Dakar, Senegal. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):587.

Ministry of Health T: Standard Treatment Guidelines & National Essential Medicines List-Tanzania Mainland. 2017.

Büdel T, Kuenzli E, Clément M, Bernasconi OJ, Fehr J, Mohammed AH, Hassan NK, Zinsstag J, Hatz C, Endimiani A. Polyclonal gut colonization with extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and/or colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a normal status for hotel employees on the island of Zanzibar, Tanzania. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(10):2880–90.

Komba EV, Mdegela RH, Msoffe P, Nielsen LN, Ingmer H. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and risk factors for thermophilic campylobacter infections in symptomatic and asymptomatic humans in Tanzania. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62(7):557–68.

Mubito EP, Shahada F, Kimanya ME, Buza JJ. Antimicrobial use in the poultry industry in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania and public health implications. Am J Res Commun. 2014;2:51–63.

Mwanza Urban Water and Sanitation Authority (MWAUWASA): Cleaning and Filtering [http://mwauwasa.go.tz/?page_id=80]. Accessed 18 Jan 2020.

Moremi N, Manda EV, Falgenhauer L, Ghosh H, Imirzalioglu C, Matee M, Chakraborty T, Mshana SE. Predominance of CTX-M-15 among ESBL producers from environment and fish gut from the shores of Lake Victoria in Mwanza, Tanzania. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1862.

Zhang S, Lin W, Yu X. Effects of full-scale advanced water treatment on antibiotic resistance genes in the Yangtze Delta area in China. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016;92(5):fiw065.

Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Okuda J, Kurazumi T, Suhara T, Ueda T, Nagata H, Morisaki H. Sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction and β-adrenergic blockade therapy for sepsis. J Intensive Care. 2017;5(1):22.

Adeyinka A, Kondamudi NP. Cyanosis; 2019.

Chand N, Sanyal AJ. Sepsis-induced cholestasis. Hepatology. 2007;45(1):230–41.

Schechner V, Nobre V, Kaye KS, Leshno M, Giladi M, Rohner P, Harbarth S, Anderson DJ, Karchmer AW, Schwaber MJ. Gram-negative bacteremia upon hospital admission: when should Pseudomonas aeruginosa be suspected? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):580–6.

Bullard KM, Dunn DL. Bloodstream and intravascular catheter infections. In: Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. edn.: Zuckschwerdt; 2001.

Russotto V, Cortegiani A, Raineri SM, Giarratano A. Bacterial contamination of inanimate surfaces and equipment in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care. 2015;3(1):54.

Moremi N, Claus H, Mshana SE. Antimicrobial resistance pattern: a report of microbiological cultures at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):756.

Gramatniece A, Silamikelis I, Zahare I, Urtans V, Zahare I, Dimina E, Saule M, Balode A, Radovica-Spalvina I, Klovins J. Control of Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in the neonatal intensive care unit in Latvia: whole-genome sequencing powered investigation and closure of the ward. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):84.

Singla P, Sikka R, Deeep A, Gagneja D, Chaudhary U. Co-production of ESBL and AmpC β-lactamases in clinical isolates of A. baumannii and A. lwoffii in a tertiary care hospital from northern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(4):DC16.

Gupta G, Tak V, Mathur P. Detection of AmpC β lactamases in gram-negative bacteria. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6(1):1.

Espinal P, Marti S, Vila J. Effect of biofilm formation on the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80(1):56–60.

Hewitt KM, Mannino FL, Gonzalez A, Chase JH, Caporaso JG, Knight R, Kelley ST. Bacterial diversity in two neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54703.

Weinstein RA, Hota B. Contamination, disinfection, and cross-colonization: are hospital surfaces reservoirs for nosocomial infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(8):1182–9.

Chen KTC. Intrapartum fever. Webpage "UpToDate", 45.0. 2012. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intrapartum-fever.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Microbiology Laboratory of the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Bugando; Healthcare workers in neonatal ICU and neonatology unit; and neonates’ mothers for their participation in this study.

Funding

This work was funded by the Antimicrobial Resistance Cross-Council Initiative through a grant from the Medical Research Council, a Council of UK Research and Innovation, and the National Institute for Health Research (Award no: MR/S004815/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS, AML, ASH and SEM designed this study. VS and DRM collected research data. VS performed laboratory procedures. VS, DK, LM and RNZ analysed and interpreted data. VS prepared the manuscript which was read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Protocols and procedures in this study were approved by Code of Conduct for Research Ethics of the Sokoine University of Agriculture with certificate number: SUA/CVMBS/R.1/2018/8 and ethically cleared by the joint CUHAS/BMC Research Ethics and Review Committee (CREC) with certificate number: CREC/298/2018. All participants were asked to sign in informed consent forms before their enrolment in this study except for participants aged < 18 years their consent of participation were provided by their parents or guardians. Detailed microbiological reports of clinical specimens were timely shared with attending doctors in respective units for proper neonates’ management.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Silago, V., Kovacs, D., Msanga, D.R. et al. Bacteremia in critical care units at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania: the role of colonization and contaminated cots and mothers’ hands in cross-transmission of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9, 58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00721-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00721-w