Abstract

Background

Forests set aside from productive forestry are often considered best conserved by non-intervention. However, biodiversity is often maintained in natural forests by a background level of disturbance, which, in some forests, takes the form of forest fires. Set-aside forests may therefore benefit from continuation of such disturbances, which, in forests under protection, must be managed anthropogenically. While the effects of prescribed burning on tree regeneration and on pyrophilous and/or saproxylic species in some regions are well known, effects on other organisms are less clear and/or consistent. It would be valuable to broaden the knowledge of how prescribed burning affects forest biodiversity, particularly because this practice is increasingly considered as a conservation management intervention. The primary aim of the proposed systematic review is to clarify how biodiversity is affected by prescribed burning in temperate and boreal forests. The ultimate purpose of the review is to investigate whether and how such prescribed burning may be useful as a means of conserving or restoring biodiversity, beyond that of pyrophilous and saproxylic species, in forest set-asides.

Methods

The review will examine primary field studies of how prescribed burning affects biodiversity in boreal and temperate forests. We will consider studies made in such forests anywhere in the world, and will include forests both in protected areas and under commercial management. Non-intervention will be used as a comparator. Relevant outcomes will include a range of measures of biodiversity, including abundance and diversity, but not of pyrophilous and saproxylic species. Relevant studies will be taken from a recent systematic map of the evidence on biodiversity impacts of active management in forests set aside for conservation or restoration. Additional searches and a search update will be undertaken in a subset of databases from the systematic map, using a search string targeted to identify studies focused on prescribed burning interventions. Searches for additional literature will be made in the bibliographies of existing reviews of forest burning. Traditional academic literature and grey literature in English, French, Swedish and Finnish will be considered. Stakeholders who engage in prescribed burning will be asked to provide relevant grey literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The biodiversity of forests set aside from forestry practice is often considered best preserved by non-intervention. However, in many protected forests, remaining biodiversity values are legacies of past disturbances, e.g. recurring fires, grazing or small-scale felling. These forests may require active management to enhance or maintain the biodiversity characteristics that were the reason for protecting them. Such management can be particularly relevant where the aim is to restore lost ecological values.

Naturally occurring fires (or wildfires) are considered to be an essential part of forest disturbance dynamics [1]. It is well documented that wildfires have always occurred and have long-term patterns (fire regimes), probably related to large-scale and long-term climate and vegetation changes [2]. In general, fires modify the structure of a forest in a way that many forest-dwelling species find beneficial and are specifically adapted to [3]. Fire regimes are very variable in their frequency, extent and intensity. This inherent variability is likely to have important impacts on forest biodiversity, but it also makes it highly challenging to explore the ecological consequences in a systematic and detailed way.

A lack of fires in areas where fires were historically common leads to a lack of specific habitats, resources or living substrates for those species that are associated with fires and other natural disturbances. This anthropogenic fire suppression has been shown to affect native forest biodiversity negatively [4], notably, for pyrophilous and several saproxylic species [5]. Furthermore, it clearly changes many characteristics of forest structure, disturbance dynamics, and succession, with equally clear consequences for forest-dwelling biota. In particular, northern Europe has seen drastic reductions in the extent and severity of forest fires, and an accumulation of dense woody vegetation. Active, policy-driven fire suppression since the mid twentieth century, particularly in managed areas, and changed landscape structure are likely key factors behind this development [6].

Prescribed burning, the planned application of fire to achieve a desired outcome, is currently used in some protected areas as an active management tool, to enhance and maintain habitats for biodiversity outcomes [7]. Prescribed burning is also commonly used for the purpose of mitigating wildfire risk by managing the accumulation of fuel in forests. Historically, this has been the primary purpose in Australia, where the practice is well advanced. In this region, there is also recognition by management authorities that planned burns have positive effects on native biota [7]. In North America, recognition of the ecological and hazard reduction benefits has been slow, particularly when fire has been publically viewed as incompatible with timber production [5]. Thus, the extent and purpose of prescribed burning varies in this region. As acceptance grows, there is interest in investigating how the amount and variability of fuel distribution will impact forest structural complexity and the biota associated with this complexity, following fires [7]. Prescribed burning for wildlife in southern Europe is far less developed than in other areas of the world, and the environmental implications remain poorly understood [8]. Across all regions, it is clear that where prescribed burning is undertaken, it requires engagement with local and regional communities, since the practice typically involves potentially contentious trade-offs [6].

Forest burning can have direct impacts on organisms, the habitat and/or indirect consequences of the beneficial effects on pyrophilous or saproxylic species. In general, the effects appear to be clear and quick, with overall positive effects on forest biodiversity [9, 10]. The immediate effects of fire on pyrophilous and saproxylic species, and also tree regeneration, are well documented. However, the impact of prescribed fire on other components of biodiversity, particularly for northern European forests are less clear and/or consistent. The relative importance of the frequency, extent and intensity of prescribed fires on restoration success also remains undetermined.

Identification of review topic

A systematic map published in 2015 [11] identified studies on a variety of active management interventions that could be useful for conserving or restoring any aspect of forest biodiversity in boreal and temperate regions. A total of 812 studies describing a variety of interventions were identified as relevant to the map. Since the map was based on Swedish initiatives, it focused on forest types that are represented in Sweden, but such forests exist in many parts of the world. The map gives an overview of the evidence base by providing a database with descriptions of relevant studies, but it does not synthesise reported results, in accordance with accepted systematic mapping guidance [12].

The map identified four potential subtopic areas that were sufficiently covered by existing studies to be included in a full systematic review. The selection of topics was also based on their significance for managers of forest reserves and other stakeholders, and on their relevance to Swedish forests, following stakeholder engagement. Two of the suggested systematic reviews are currently in progress [13, 14].

A third suggested review topic was the effects of prescribed burning on the diversity of species other than those directly dependent on fire and dead wood. The direct impact of fire on tree regeneration, pyrophilous and saproxylic species have been well studied, and one of the systematic reviews in progress is investigating the effect of dead-wood manipulation (e.g. through burning) on biodiversity in forests [13]. Furthermore, one recent systematic review investigated the impact of restoration burning on tree regeneration in boreal forests [15]. The systematic review described in this protocol is focused on effects of prescribed burning on other, less well-known aspects of biodiversity.

It would be valuable to broaden the knowledge of how prescribed burning affects forest biodiversity, particularly because such effects could be viewed as either negative or positive. Additionally, the practice of burning is now fairly common in temperate and boreal forests worldwide, further indicating the need for thorough investigation of its impacts on species other than those that can be considered as pyrophilous or saproxylic. For example, the Life + Taiga project is a five-year European Union funded programme (2015–2019) recently initiated in Sweden [16]. The project involves 14 regional County Administrative Boards and aims to perform 120 controlled fires in boreal forests, with the aim of conserving and restoring biodiversity.

A total of 227 studies in the systematic map of management interventions in temperate or boreal forests [11] described effects of prescribed burning. Additional studies in the topic area are likely to have become available since the last search for evidence was undertaken by the map authors in 2015.

The current literature lacks a recent review assessing the full evidence base on the impact of prescribed burning on biodiversity of temperate and boreal forests worldwide. This review will address this need, by exploring the often-ignored wider impacts of prescribed burning.

Objective of the review

The primary aim of the proposed systematic review is to clarify if, and how, the biodiversity of boreal and temperate forests is affected by prescribed burning. Only burning which is undertaken as a controlled management practice will be considered as relevant to this review, i.e. wildfires will not be considered. Direct effects on pyrophilous and saproxylic species and tree regeneration will not be included.

The ultimate purpose of the review is to investigate whether prescribed burning is useful as a means of conserving or restoring biodiversity in forest set-asides (excluding tree regeneration, pyrophilous and saproxylic species), and if so, what conditions increase its effectiveness. We will also include any relevant studies made in forests under commercial management.

The review will follow the guidelines for systematic reviews in environmental management issued by the collaboration for environmental evidence [17].

Question

What is the effect of prescribed burning in temperate and boreal forest on biodiversity, not including pyrophilous and saproxylic species?

Components of the question:

Population: Boreal and temperate forests.

Intervention: Prescribed burning.

Comparator: Non-intervention or alternative levels of intervention.

Outcomes: Biodiversity measures, including diversity, richness, abundance and composition of species (excluding pyrophilous and saproxylic species).

We propose including all measures of biodiversity, species richness, abundance and composition. Some studies may report changes in species composition after fire by ordination methods. Data for meta-analysis is not easily extractable from such studies, but these studies will be considered as a part of the narrative review of the retrieved, relevant studies.

Methods

Searches

The searches described below together constitute a comprehensive search strategy that equates to a search of four databases/search facilities (CAB Abstracts, Web of Science Core Collections, Scopus and Google Scholar) using the full string in Table 1.

We outline specific steps taken in each database to adapt this string to the specific search facility whilst also making use of the existing systematic map database (Bernes et al. [14]).

The systematic map search only retrieved studies that had a “forest type” term. This restriction may have missed some vital evidence relevant to our review. We therefore aim to be more inclusive, using a search strategy to also capture studies that did not happen to describe a forest type in the title, abstract or keywords.

Our database searching approach includes not only the systematic map burning studies, but also searches all forest types for burning studies in CAB abstracts, and supplemental searching for all forest types for burning studies in WoSCC and Scopus, along with an update to the present day for these two databases, along with a final search (not restricted by date) in Google Scholar. Table 2 provides the number of records retrieved by scoping searches using this search strategy.

Studies identified by the systematic map search

The systematic map which informed this systematic review identified studies of the biodiversity impacts of active management in forest set-asides (Bernes et al. [11]). The search string used in the map is presented in Table 3.

Of the 812 studies in the map, 227 reported on the impact of prescribed burning, and we will consider these as potentially relevant to our review question.

The original systematic map was based on searches using 13 publication databases, 2 search engines, 24 specialist websites and 10 literature reviews [1]. The majority of searches were performed in May–August 2014. In March 2015, a search update was made using Web of Science and Google Scholar.

Supplemental search for all forest types (up to 2014)

To include studies of burning for all forest types, which may have been missed by the systematic map search, we will search two databases, Web of Science Core Collections and Scopus, up to 2014. The databases above were chosen because, in our experience of systematic reviewing in a wide range of topics in the environmental sciences, they represent the largest sources of retrieved evidence and because significant duplication was detected across the other databases searched within the systematic map. We will avoid unnecessary duplication of effort by removing the portion of studies already screened in the systematic map (for the years up to 2014). This is achieved by using a “NOT” operator for the “forest type” substring, Table 4.

Search update (up to 2016)

In order to identify recently published literature in Web of Science Core Collections and Scopus, we will also perform a search update for 2015–2016 using the search string presented in Table 5. A similar string will be used to search for evidence from all years up to 2016 in the CAB abstracts database. This database represents a large source of evidence in the applied life sciences, in particular, agriculture and the environment, and was not included in the systematic map searches.

Google Scholar search

A search in Google Scholar will also be carried out as follows:

With all of the words: forest burn.

With at least one of the words: diversity biodiversity “species richness” “keystone species” “umbrella species” “rare species” “species density” indicator abundance “forest structure” habitat.

The first 1000 hits in Google Scholar (sorted on relevance) will be examined for relevant evidence.

Where possible, language restrictions will be applied to limit to the English, French, Finnish and Swedish languages. No document type restrictions will be applied. Scoping searches have indicated that these searches will retrieve around 8500 records, Table 2. The majority of the 3800 records from CAB abstracts were studies based in tropical forests, most of which could therefore be rapidly excluded at the title (or abstract) stage.

Organisational searches

Websites of the specialist organisations listed below will be searched for links or references to relevant publications and data, including grey literature.

Ancient Tree Forum (http://www.ancient-tree-forum.org.uk).

Bureau of Land Management, US Dept. of the Interior (http://www.blm.gov).

Environment Canada (http://www.ec.gc.ca).

European Commission Joint Research Centre (ec.europa.eu/dgs/jrc).

European Environment Agency (http://www.eea.europa.eu).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (http://www.fao.org).

Finland’s environmental administration (http://www.ymparisto.fi).

International Union for Conservation of Nature (http://www.iucn.org).

Metsähallitus (http://www.metsa.fi).

Natural Resources Canada (http://www.nrcan.gc.ca).

The Nebraska Prescribed Fire conference (http://outdoornebraska.gov/prescribedfire/).

Nordic Council of Ministers (http://www.norden.org).

Norwegian Environment Agency (http://www.miljødirektoratet.no).

Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute (http://www.skogoglandskap.no).

Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (http://www.nina.no).

Parks Canada (http://www.pc.gc.ca).

Society for Ecological Restoration (http://www.ser.org).

Swedish County Administrative Boards (http://www.lansstyrelsen.se).

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (http://www.naturvardsverket.se).

Swedish Forest Agency (http://www.skogsstyrelsen.se).

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (http://www.slu.se).

UK Environment Agency (http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk).

United Nations Environment Programme (http://www.unep.org).

United States Environmental Protection Agency (http://www.epa.gov).

United States National Parks Service (https://www.nps.gov/).

US Forest Service (http://www.fs.fed.us).

Bibliographic searches

A comprehensive search for additional potentially relevant studies will be made in the bibliographies of existing reviews of prescribed forest burning. Moreover, the working group and advisory team will use national and international contacts to retrieve information on current research related to the topic of the review, and also to find grey literature, including reports and theses.

Article screening and study inclusion criteria

Screening process

Articles will be evaluated for inclusion at three successive levels, using the study inclusion criteria described below. First, they will be assessed by title. Next, each article found to be potentially relevant on the basis of title will be judged for inclusion on the basis of abstract. Finally, each article found to be potentially relevant on the basis of abstract will be judged for inclusion based on the full text. At all stages of this screening process, the reviewer will tend towards inclusion in cases of uncertainty (including where abstracts are deficient or missing). A second reviewer will independently evaluate a subset of the studies at each of the levels of inclusion. If the reviewers disagree on a study’s relevance, a team discussion will be held to make a consensus decision on inclusion. The team will work through a sample of studies which meet the inclusion criteria and discuss any relevance issues before screening the rest of the retrieved studies.

A list of studies rejected on the basis of full-text assessment will be provided in an appendix together with the reasons for exclusion.

Inclusion criteria

In order to be included, each study must pass each of the following criteria (a subset of those used for the systematic map):

Relevant populations

Forests in the boreal or temperate vegetation zones.

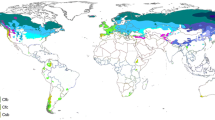

Any habitat with a tree layer is regarded as forest, which means that studies of e.g. wooded meadows and urban woodlands may be included. As an approximation of the boreal and temperate vegetation zones we will use the cold Köppen-Geiger climate zones (the D zones) and some of the temperate ones (Cfb, Cfc and Csb), as defined by Peel et al. [18]. The other temperate Köppen-Geiger climate zones are often referred to as subtropical and are therefore considered to fall outside the scope of this review.

Nevertheless, forest stands dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) will be considered as relevant even if located outside the climate zones mentioned above. These forests constitute a well-studied North American habitat type that shares several characteristics with the pine forests in boreal and temperate regions.

Relevant types of intervention: Prescribed burning

Relevant type of comparator: Non-intervention or alternative levels of intervention. We acknowledge that, in practice, prescribed burning may be combined with other interventions, such as pre-treatment thinning of the stand. If the comparator reported in such a case does not include the pre-treatment intervention, the study is confounded. These studies will be included, listed separately as “confounded evidence” and analysed in a separate quantitative analysis, if sufficient data exists to do so.

Both temporal and spatial comparisons of how prescribed burning affects biodiversity are considered to be relevant. This means that we will include both ‘BA’ (Before/After) studies, i.e. comparisons of the same site prior to and following an intervention, and ‘CI’ (Control/Impact) studies, i.e. comparisons of treated and untreated sites (or sites that had been subject to different kinds of treatment). Studies combining these types of comparison, i.e. those with a ‘BACI’ (Before/After/Control/Impact) design, will also be included.

Relevant types of outcome: Diversity, richness, composition and abundance of communities or abundance of specific species. Tree regeneration (saplings and seedlings) and abundance or diversity of pyrophilous and saproxylic species are not eligible outcomes.

Relevant type of study: Primary field studies (both observational and manipulative)

Based on this criterion, we will exclude e.g. simulation studies, review papers and policy discussions.

Language: Full text written in English, French, Swedish or Finnish. This selection reflects the language capabilities of the working group and their respective institutions, from which assistance may be provided.

Study quality assessment

Studies that have passed the relevance criteria described above will be subject to critical appraisal. Based on assessments of their internal validity (quality) and external validity (generalisability), they will be categorised as having high, medium or low susceptibility to bias.

Studies will be excluded from full synthesis due to high susceptibility to bias (low validity) if any of the following factors apply:

-

Methodological description insufficient.

-

Intervention and comparator sites not well-matched.

-

Intervention not consistently or realistically applied (i.e. low generalizability).

Confounding factors may include interventions performed in addition to prescribed burning. Studies of such interventions will be classified as “subject to confounding factors” and assessed separately from studies focusing purely on prescribed burning.

These studies will be subject to the same assessment (high, medium or low validity) as all other studies.

Studies that are not excluded due to low validity will be considered to have medium susceptibility to bias (medium validity) if any of the following factors apply:

-

Non-replicated intervention.

-

Location of study plots potentially biased.

-

BA study (not CI or BACI).

-

No useful data on variance or sample sizes.

-

Limited description of intervention strength.

If none of the above factors apply, the study will be considered to have low susceptibility to bias (high validity).

Additional or more specific quality criteria, such as appropriate spatial scale of study, may be developed as the review proceeds.

Detailed reasoning concerning critical appraisal will be recorded in a transparent manner. In general, a study will be assessed by one reviewer, but final decisions on how to judge doubtful cases will be taken by the review team as a whole. A list of studies rejected on the basis of this assessment will be provided in an appendix together with the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction strategy

Outcome means, measures of variation (standard deviation, standard error, confidence intervals, etc.) and sample sizes will be extracted from tables and graphs, using image analysis software when necessary. Data on interventions and other potential effect modifiers will also be extracted from the included articles. Extracted data will be checked by a second reviewer, and amended following discussion, as necessary.

It may in some cases be useful to ask authors of relevant articles to supply data in digital format. This will primarily be done where useful data have been published in graphs from which they are difficult to extract accurately enough, or when it is known or assumed that considerable amounts of relevant but unpublished data may be available in addition to the published results. If raw data are provided, the working group will calculate summary statistics.

Potential effect modifiers and reasons for heterogeneity

To the extent that data are available, the following potential effect modifiers will be considered and recorded for all studies included in this review:

-

Geographical coordinates.

-

Altitude.

-

Climate (and climate change).

-

Mean age of forest stand.

-

Dominant tree species.

-

Forest density (e.g. basal area or overstory canopy cover).

-

Areal extent and seasonality of intervention.

-

Intervention type (single or multiple point burning).

-

Size of plots where data were sampled.

-

Time elapsed from intervention to final data sampling.

-

Intervention strength (severity, e.g. the depth of charring, and intensity- the energy released [19]).

-

Other interventions at study sites (harvesting, thinning, understory removal, grazing etc.)

-

Landscape aspects (such as degree of isolation).

-

History of land use and protection.

-

Management history (e.g. past fire regime).

This list is not exhaustive, and a final list of effect modifiers and causes of heterogeneity to be recorded will be established as the review proceeds.

Data synthesis and presentation

A narrative synthesis of data from all studies included in the review will describe the strength and validity of the evidence base along with the study findings. Tables and figures will be produced to summarise these results. Where studies report similar outcomes, meta-analysis may be possible. In these cases, effect sizes will be standardised and weighted appropriately. Details of the quantitative analysis will only be known when full texts have been assessed for their contents and critically appraised.

If meta-analysis of effect sizes is possible, it will take the form of random-effects models. Meta-regressions or subgroup analysis of categories of studies will also be performed where sufficient studies report common sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis using critical appraisal categories will be carried out where possible. Overall management effects will be presented visually in plots of mean effect sizes and variance.

References

Agee JK. Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1993.

Pyne SJ. Burning bush: a fire history of Australia. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1998.

Abrams MD. Fire and the development of oak forests. Bioscience. 1992;42:346–53.

Falcucci A, Maiorano L, Boitani L. Changes in land-use/land-cover patterns in Italy and their implications for bio-diversity conservation. Landscape Ecol. 2007;22:617–31.

Ryan KC, Knapp E, Morgan Varner A. Prescribed fire in North American forestsand woodlands: history, current practice and challenges. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11:e15–24.

Russell-Smith J, Thornton R. Perspectives on prescribed burning. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11:e3.

Burrows N, McCaw L. Prescribed burning in southwestern Australian forests. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11:e25–34.

Fernandes PM, Davies GM, Ascoli D, Fernández C, Moreira F, Rigolot E, Stoof CR, Vega JA, Molina D. Prescribed burning in southern Europe: developing fire management in a dynamic landscape. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11:e4–14.

Burrows ND. Linking fire ecology and fire management in south-west Australian forest landscapes. For Ecol Manage. 2008;255:2394–406.

Wittkuhn RS, McCaw L, Wills AJ, Robinson R, Andersen AN, Van Heurck P, Farr J, Liddelow G, Cranfield R. Variation in fire interval sequences has minimal effects on species richness and composition in fire-prone landscapes of south-west Western Australia. For Ecol Manage. 2011;261:965–78.

Bernes C, Jonsson BG, Junninen K, Lõhmus A, Macdonald E, Müller J, Sandström J. What is the impact of active management on biodiversity in forests set aside for conservation or restoration? A systematic map. Environ Evid. 2015;2015(4):25.

James KL, Randall NP, Haddaway NR. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environ Evid. 2016;5:7.

Bernes C, Jonsson BG, Junninen K, Lõhmus A, Macdonald E, Müller J, Sandström J. What are the impacts of dead-wood manipulation on the biodiversity of temperate and boreal forests? A systematic review protocol. Environ Evid. 2016;4(1):1.

Bernes C, Jonsson BG, Junninen K, Lõhmus A, Macdonald E, Müller J, Sandström J. What are the impacts of manipulating grazing and browsing by ungulates on plants and invertebrates in temperate and boreal forests? A systematic review protocol. Environ Evid. 2016;5:17.

Matheis M. Does restoration fire enhance the regeneration of deciduous trees in boreal forests? A systematic review. Master by Research in Biology, Mittuniversitet, 2015.

Life + Taiga. http://lifetaiga.se/om-taiga/. Accessed 25 June 2016.

Collaboration for environmental evidence. Guidelines for systematic reviews in environmental management. Version 4.2. http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Review-guidelines-version-4.2-final.pdf. Accessed 29th June 2016.

Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2007;11:1633–44.

Keeley JE. Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: a brief review and suggested usage. Int J Wildland Fire. 2009;18:116–26.

Authors’ contributions

The manuscript was drafted by JE and NH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The review will be financed by the Mistra Council for Evidence-Based Environmental Management (EviEM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Eales, J., Haddaway, N.R., Bernes, C. et al. What is the effect of prescribed burning in temperate and boreal forest on biodiversity, beyond tree regeneration, pyrophilous and saproxylic species? A systematic review protocol. Environ Evid 5, 24 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0076-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0076-5