Abstract

Background

The global decline of marine biodiversity and the perceived need to protect marine ecosystems from irreparable alterations to ecosystem functioning and ecosystem service provision have produced an extensive range of spatial management measures (SMMs). The design of SMMs is a complex process often involving the integration of both conservation objectives and socio-economic priorities and the resultant trade-offs are highly dependent on the management regime in place. Future marine management is likely to involve greater use of different forms of protected areas with differing levels of protection, particularly for sites where there are multiple competing demands. Consequently, evaluations of the characteristics that enable different forms of SMMs to successfully achieve their objectives are required to inform future conservation networks. The objective of this evidence-based analysis is to assess and compare the biological effects of different forms of SMMs with the aim of providing additional guidelines and insight into the design of future SMMs.

Methods

SMMs will be grouped into four main categories according to the degree of management enforcement (marine reserve, marine protected area, partial permanent protection, partial temporal protection). To identify and collate evidence to address these questions a comprehensive systematic search of peer-reviewed scientific literature and grey literature will be undertaken. Articles will be examined for relevance using specified inclusion criteria and the included papers will be critically appraised. Studies that examine the effects on an outcome comparing at least one spatial management measure vs no protection (open access area) or between interventions will be considered. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression will be performed to explore variation in biological effects in relation to covariates (SMMs parameters, habitat and species functional and biological traits).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Marine spatial management has become a major focus in marine ecology, fisheries management and conservation biology and the number and type of spatial management measures (henceforth referred to as SMMs) has grown worldwide during the last two decades [1–3]. Marine spatial management measures have been increasingly recognised as essential in safeguarding ecosystem services and protecting a sample of biological resources and are proposed as efficient tools to maintain and manage human activities [4, 5]. The trade-offs between ecological/conservation objectives and socio-economic priorities in the designation and continued operation of a SMM are highly dependent on the management regime in place. For example socio-economic costs associated with a SMM depends to some extent on the level of protection afforded by the SMM and the activities displaced; high levels of protection may require more stringent management regimes (including greater levels of enforcement and monitoring) compared to lower levels of, or temporary, protection. Such trade-offs require consideration when designing new SMMs and greater evidence regarding the biological effects of different SMMs is required to enable efficient design which minimises socio-economic impacts while maximising the potential for biodiversity gain.

Both the global decline of marine biodiversity and the resulting need to protect marine ecosystems from irreparable functioning and services alterations have booster the number of spatial management measures up to date in place [6]. With recognition of this, improved understanding of the types and effectiveness of spatial management approaches together with ecological and socio-economic evidence assessment and gap analysis techniques, have been developed to increase efficiency in the selection of areas for protection [7].

Protected areas have been recognised as cornerstones of conservation strategies, human activity regulation and resource management at sea and, in a wider social and cultural perspective, represent essential tools to protect vulnerable human societies and safeguard high-value natural resources [4]. To date, the need to minimise anthropogenic impacts and to increase the ecological resilience of response to a changing climate has resulted in an astonishing variety of spatial management measures differing in size, location, level of protection (enforcement), management approaches and objectives [6]. Spatially based management approaches encompass a wide range of tools reflecting a range of management aims, from restriction measures and no-take zones to partial protection measures in the context of multiple-use objectives and ocean zoning. Moreover, the design of spatial management measures has become increasingly complex with both conservation goals and socio-economic considerations at multiple levels being integrated in order to limit “trade-offs” in different designs. The variety in designs often reflects the different contexts (e.g. environmental, social, economic and political scenarios) in which conservation is being undertaken.

In this complex context we propose a global scale evidence-based analysis to compare and assess the effects of spatial management measures on marine biodiversity and, where possible, their ability to meet their conservation objectives (although note that these are often broad and may not be available for all SMMs considered). Additionally, useful insights and guidelines to appropriately design future spatial management measures might be provided.

Elevated from conventional reviews, systematic reviews (SR) can provide a comprehensive, policy-neutral, transparent, reproducible and robust assessment and summary of available evidence [8, 9]. Moreover the application of SR has been identified as a useful tool to inform environmental policy due to the strict methodological protocol adopted to minimize the chance of bias and improve transparency, repeatability and reliability of the outcomes of the review [9–11]. Here we present the first step of the SR procedure consisting in setting a systematic review protocol.

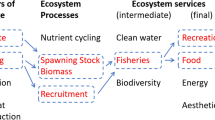

To provide a global comparative evaluation of the biological effects of SMM we have grouped SMMs into four main categories according to the degree of management enforcement and permissible activities (see Fig. 1, Additional file 1 for more details). These categories are: marine reserves (MRs) (highly protected areas set aside to protect biodiversity by conserving intact ecosystems, preventing all destructive and extractive activities, recreational human activities are allowed), marine protected areas (MPAs) (less strictly protected than marine reserves, set aside to protect, manage and preserve the natural condition, regulated human activity are allowed), partial permanent protection (PPP) (regular, continuous, active more localised management interventions to maintain and protect specific species, habitats or parts of ecosystems) and partial temporal protection (PTP) (time-limited spatial closure measures aimed at particular species or groups and activities, where other human activities are not curtailed).

We will synthesize data on SMM performance from studies that have made direct comparisons between (1) at least one SMM and open access areas (OA) and (2) at least two or more SMMs to examine how the level of protection inside each SMM determines the effect on marine biodiversity.

A limited number of environmental SRs has been previously performed on MPAs to analyse evidence of conservation and restoration effects on target-fish populations, or to test the ecological effects of partially protected areas [12–16]. We build on a similar SR undertaken by Sciberras et al. who considered the relative effects of partially protected areas against no-take reserves (i.e. marine reserves) and open access areas on marine biodiversity. Sciberras et al. found that the benefits (e.g. higher density and biomass of fish) offered by SMMs increases with increasing protection. This suggests that while partially protected areas do not deliver the same benefits as no-take reserves they are a valuable biodiversity conservation tool. With an increasingly crowded seascape the marine conservation toolkit will therefore likely involve greater use of partially protected areas to enable trade-offs to be minimised. Further consideration of the characteristics of these areas which offer the greatest benefits to marine biodiversity are therefore required to inform future management decisions. We therefore consider the effect of partially protecting areas on a permanent or temporary (e.g. fisheries closures) basis. In addition, we update and expand the review of Sciberras et al. to include studies published since completion of their SR searches (last updated 2011), as well as searching specifically for a greater range of SMMs (e.g. marine conservation zones, fishery exclusion zones etc.; see Additional file 2). The proposed SR approach will therefore compare the biological effects of four different SMM categories against no protection, the status quo (Fig. 1). Biodiversity responses, both in term of taxonomical and functional diversity, to a wide range of interventions from numerous studies encompassing a gradient of management enforcement will be collated. This global approach will enable improvements to current marine spatial planning approaches by collating existing available knowledge on design and biological effects and therefore promoting appropriate measures for marine resource protection.

Objectives of the review

This protocol aims to set out the methods for a systematic review into the effects of SMMs in protecting marine biodiversity around the world. The systematic review aims to explore and compare the variety of effects that the main current spatial management measures, SMMs, have on marine biodiversity (all marine species considered animal, vegetal, vertebrate, invertebrate, target and non-target species) globally in terms of density, biomass, species richness and biological and life history (LH) traits (body size, size at maturity, longevity, type of reproduction, sex ratio, mobility).

Primary question

What are the comparative biological effects of SMMs in protecting marine biodiversity? Here, we examine whether SMMs worldwide deliver effective conservation of marine biodiversity. To address this question, studies that examine the effects on an outcome comparing at least one spatial management measure (intervention) vs no protection (open access area, OA) or between interventions (as OA could be not always available) will be considered (see Additional file 2: Table S1 for more details on PICO elements of the question).

Secondary questions:

-

1.

How does the effect of management measures on biodiversity vary in relation to SMMs parameters? (latitude, age, size).

-

2.

How does the effect of management measures on biodiversity vary with habitat? (habitat-level analysis).

-

3.

How does the effect of management measures on biodiversity vary in relation to taxon type? (functional species-level analysis).

The biological effect of SMMs will be examined including both the protection parameters (latitude, age, size, distance between interventions) and habitat and species responses (more details provided in section: “potential reason for heterogeneity”).

Methods

Search strategy and terms

A comprehensive search of peer-reviewed scientific literature and grey literature will be undertaken in order to compile a database of studies that documents and compares the biological effects of the considered spatial management measure (SMMs): marine reserves (MRs), marine protected areas (MPAs), partial permanent protection (PPP) and partial temporal protection (TP) measures and open access areas (OA). Searching will be carried out across a range of resources in order to minimise the possibility of publication and related biases [17]. In addition relevant review articles will be subjected to bibliography checks for relevant references. At the search stage, the comparison between interventions (SMMs) may be observed through several approaches (study designs): before-and-after intervention, or no-interventions (control) versus intervention (impact), or both (i.e. before after control impact, BACI), or intervention versus alternative intervention. Studies will be treated the same, but differently coded for easy identification and subsequent separation during the analysis stage.

To guarantee a good balance between sensitivity and specificity of the search, a scoping search phase was performed. A scoping search process, using several bibliographic databases, estimated the volume of relevant literature and set the search strategy by determining the most appropriate search terms (see Additional file 2 for a full list of the search term combinations used).

A complex search string was created to be used in databases and websites that allow complex search through advanced search options (Additional file 2A–C). The Boolean operators “AND/OR” were used where appropriate and the search was undertaken across title, keywords and abstract. Search terms were based on the following phrases (where * denotes a wildcard to search for alternate endings):

“marine protected area*” OR “fishery exclusion zone*” OR “economic exclusion zone*” OR (“no take zone*” OR “no take area*” OR “no-take zone” OR “no-take area”) OR (“special protection zone*” OR “special protection area” OR “SPA”) OR (“site of community importance” OR “site of community interest”) OR “partial protection” OR “temporal protection” OR “permanent protection” OR “marine reserve*” OR “buffer zone*” OR “closed area*” OR “marine park” OR “marine sanctuary” OR “restricted area*” OR “nursery area*” OR “fishing gear restriction*” OR “integrated coastal zone management” OR “ICZM” OR (“special area* of conservation” OR “SAC”) OR (“site of special scientific interest” OR “SSSI” OR “marine conservation zone” OR “MCZ”) OR “mari* spatial planning” OR “marine directive” OR “mari* spatial management” OR “vulnerable” OR “protection effect*” OR “restoration effect” OR “harvest refug*”

AND

“density” OR “abundance” OR “biomass” OR “*diversity” OR “richness” OR “evenness” OR “Shannon” OR “species number” OR “size” OR “length” OR “life history trait*” OR “LH trait*” OR “maturity” OR “longevity” OR “reproduction” OR “sex” OR “mobility” OR “Biological trait*”

AND

“sea” OR “marine” OR “ocean” OR “marine ecosystem*”

The complex search string will be replaced by simple strings, modified according to the search functionality of the databases and websites that do not allow advanced search. In this case search terms will be limited as website search engines generally only accept simple search terms (Additional file 2B).

Search sources

Databases

The following computerised databases will be searched:

-

1.

ISI Web of Knowledge.

-

2.

Scopus.

-

3.

CAB Abstracts.

-

4.

Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts (since 1971).

-

5.

Directory of Open Access Journal.

Search engines and additional specialist sources

The search will be limited to Word, PDF and/or Excel documents and the first 50 hits will be examined for appropriate data as recommended by the CEE review guidelines [18]. The following general search engines will be used.

Additional searches will be carried out in specific websites of relevant specialist organisations and management-related projects listed below:

-

1.

WWF—Marine Protected Areas—http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/how_we_work/conservation/marine/protected_areas/.

-

2.

National Marine Protected Area Center—NOAA—http://marineprotectedareas.noaa.gov/.

-

3.

International Union for Conservation of Nature—http://www.iucn.org.

-

4.

Maritime Affairs, European Commission—http://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/index_en.htm.

-

5.

FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture—http://www.fao.org/fishery/en.

-

6.

Marine Protected Areas—National Ocean Service—NOAA—http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/ecosystems/mpa/.

-

7.

Protect Planet Ocean—The WCPA Marine Protected Area—http://www.protectplanetocean.org/.

-

8.

An Interactive Tool: EMPAFISH—http://www.empafish-mpa.org.uk/.

-

9.

Australian Marine Conservation Society—http://www.marineconservation.org.au/.

-

10.

Marine Protected Area Governance (MPAG)—http://www.mpag.info/.

-

11.

NOAA National Marine Sanctuaries—http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/.

-

12.

California Marine Sanctuary Foundation—http://www.californiamsf.org/.

-

13.

US Environmental Protection Agency—http://www2.epa.gov/.

-

14.

NOAA Fisheries: Home—http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/.

-

15.

Marine protection—Seafish—http://www.seafish.org/responsible-sourcing/marine-protection.

-

16.

Marine Management Organisation—GOV.UK—https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/marine-management-organisation.

-

17.

Joint Nature Conservation Committee: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk.

-

18.

Lundy Field Society—Conservation work—https://www.lundymcz.org.uk/conserve/ntz.

-

19.

Marine Protected Areas in the UK—JNCC—http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/.

-

20.

Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea Mediterranean Sea and Contigous Atlantic Area—http://www.accobams.org/.

-

21.

OSPAR—http://www.ospar.org/.

-

22.

Oceana MedNet—http://oceana.org/.

-

23.

MED Integrated Coastal Zone Management-Mediterranean Coast—http://iwlearn.net/iw-projects/4198PEGASO project Indicators for Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean and Black Seas—http://www.pegasoproject.eu/project-overview.

-

24.

United Nations Environment Programme—http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/.

-

25.

Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning—NOAA—http://www.cmsp.noaa.gov/.

Specific sections and links to reports, websites, publications and related bibliographies will be searched in detail. Authors of relevant articles will be contacted for further recommendations, for missing data or for provision of any unpublished material.

Bibliographies

To identify any additional references a hand search will be performed on the bibliographies of relevant review articles on spatial management measures identified through our systematic search.

Article screening and study inclusion criteria

The results of each search will be screened for relevance. A bibliographic software package (endnote) will be used to organise all references retrieved from computerised databases. Duplicates will be removed and articles not relevant or that do not contain relevant information or data removed. Through a three stage screening process (title–abstract–full text) eligible studies to include in the review will be identified. The decision of inclusion criteria is one of the most influential decisions in the review process; at each stage studies will be selected to meet specific inclusion criteria chosen to minimise biases and human error, if there is insufficient information to exclude an article it will be retained until the next stage. The adoption of inclusion criteria, mainly based on the presence of PICO elements components (population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, to see Additional file 2: Table S1 for more details), will guarantee a transparent screening process based upon congruency with the review questions, relevance and methodology quality [19]. In the first instance, the title of articles will be assessed in order to remove spurious citations and then abstracts will be assessed according to these inclusion criteria.

Abstract inclusion criteria:

-

Relevant population: at least a component of marine biodiversity.

-

Type of intervention(s): one or more of the spatial marine managements measures SMMs categories and a comparator (see Additional file 1 for more details).

-

Type of outcome(s): modification in biomass, density or other abundance measures, species richness or other diversity measures, changes in community composition/structure (at least one of those in Additional file 2: Table S1).

Articles remaining after this filter will be considered at full text.

Full text inclusion criteria:

-

Relevant population: study that reports biological data of marine biodiversity components (vegetal or animal realms) of individual species, community or population level; study that reports exploitation status (i.e. target, non-target species, threat status).

-

Type of intervention(s): study that reports at least the comparison between an intervention (SMM) and no intervention (open access areas), or comparison between more than one intervention (Additional file 1 for further details on SMMs).

-

Types of comparator: no intervention or alternative intervention.

-

Type of outcome(s): study that reports at least a measure of density, biomass, diversity components and recovery rate of marine population.

-

Relevant types of study design: study that reports at least one of the following study designs: before-and-after intervention, no-interventions (control) versus intervention (impact) spatial comparison, both (i.e. before after control impact, BACI), intervention versus alternative intervention. Study that reports mean and sample size values (e.g. number of transects or point counts) and an appropriate variance measure (SD, SE, variance, 95 % CI) at each intervention will be recorded.

If needed, authors of relevant articles and subject experts will be contacted to clarify study eligibility (to request further advice and information, such as missing data and additional references). Articles with no data or characterised by: pseudoreplication, significant flaw in the method or analytical techniques, incorrect estimated baseline of protection or management will be excluded. An additional file of articles excluded at full text will be provided with reasons for exclusion.

To measure the effect of between-reviewer variance in assessing relevance the kappa statistic will be calculated [20]. Two reviewers will apply the above inclusion criteria to a subsample of 10 % of articles, or 100 articles (whichever is greater), at the start of the abstract screening stage. The kappa statistic estimates the level of agreement between reviewers, a rating of “substantial” (0.5 or above) is recommended to pass the assessment [18]. If comparability is not achieved the same reviewers will discuss the discrepancies and the scope and interpretation of the question elements will be redefined with potential modification of the criteria specification. After this agreement appraisal and related discussion the inclusion criteria will be applied to the rest of the citations by one reviewer.

Critical appraisal of study quality

Articles accepted at full text will be included in the review and reported studies subject to critical appraisal according to their design and quality. Reviewers will assess the methodologies used in all studies reported in articles accepted at full text. Two reviewers will examine a random subset of at least 25 % of the included studies to assess repeatability of study quality assessment. Variation in methodological and analytical quality of scientific studies will be checked [11, 21–23]. For each study design elements that reduced susceptibility to bias will be recorded. Following the same approach applied by Sciberras et al. [24] the articles will be categorised according to the study design, respectively into: before after control impact (BACI) studies, control impact (CI) studies and before after (BA) studies; variation to spatial and temporal scale and habitat heterogeneity will be take into account as the two main sources of bias. BACI studies, accounting both spatial and temporal variability in the environment [12, 24, 25], will be selected as the best design to allow the detection of the effectiveness of interventions on marine biodiversity without any inferences (less risk from bias). Subsequently, the influence of sampling design on the magnitude of the response to interventions will be explored by running a sensitivity analysis using all studies and those with BACI design only.

Studies containing information of poor or deteriorated enforcement of intervention will be excluded from the analyses. Additionally, the level of replication (sampling effort and number of included SMMs) will be recorded to check for study reliability.

Potential reasons for heterogeneity

Several factors might be sources of heterogeneity and affect the effects of interventions including:

-

intrinsic factors of the intervention measures (latitude, age, size and distance between interventions)

-

differences between outcomes or natural recoverability of biodiversity will be depend both on taxon type (e.g. animal, vegetal, vertebrate, invertebrate, target and non-target species) and habitats (depth and sediment features).

To account for potential bias due to differences in habitat among the interventions (SMMs) and control sites (baseline differences) in the comparison between interventions, a sensitivity analysis will be conducted in parallel to the main analysis to examine the influence of including studies where habitat variation (e.g. substratum type, substratum composition and complexity, rugosity and exposure) affects the overall magnitude and direction of the intervention effect [26, 27].

Data extraction strategy

Articles accepted at full text will be recorded in a database (Additional file 3). Data extraction will be undertaken using a review-specific data extraction form (sensu Lipsey and Wilson [28]). Density, abundance, biomass, length and diversity metrics will be treated as continuous variables. Sample sizes, means and variance (or other variance measures including standard deviation, standard error, 95 % confidence interval) values will be extracted as presented from tables or within the text. Different taxa were disaggregated as far as possible. Multiple non-independent data-sets may be extracted from each article, for example where different depths or habitats within an intervention and adjacent open access area are surveyed and data are also aggregated at the intervention level to maintain independence. Data from figures will be extracted using the data-extraction software PlotDigitizer.

Data synthesis

The review will include multiple comparisons and meta-analysis between all possible pairs of interventions. Previous reviews [12, 15, 16, 29] illustrate that sufficient data with comparators are available for meta-analysis, but that investigations of heterogeneity are limited by data availability. Our synthesis will therefore consist of meta-analyses to address the primary question with meta-regression and subgroup analyses used to investigate reasons for heterogeneity between studies.

Variables that affect the effectiveness of intervention measures will be classified. Responses of specific taxa will be treated as independent observations so as to investigate the effectiveness of different interventions on the response of the population, regardless of taxa. The response will be measured by the percentage difference of the population before and after (or impact/control) the establishment of the intervention, or between different sites of a known gradient of interventions.

References

Sarkar S, Pressey RL, Faith DP, Margules CR, Fuller T, Stoms DM, Moffett A, Wilson KA, Williams KJ, Williams PH, Andelman S. Biodiversity conservation planning tools: present status and challenges for the future. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2006;31:123–59.

McLeod E, Salm R, Green A, Almany J. Designing marine protected area networks to address the impacts of climate change. Front Ecol Environ. 2009;7:362–70.

Jones PJS. Governing marine protected areas: resilience through diversity. London: Routledge; 2014. p. 240.

Halpern BS. The impact of marine reserves: do reserves work and does reserve size matter? Ecol Appl. 2003;13(Suppl 1):117–37.

Lester SE, Halpern BS, Grorud-Colvert K, Lubchenco J, Ruttenberg BI, Gaines SD, Airamé S, Warner RR. Biological effects within no-take marine reserves: a global synthesis. Marine Ecol Prog Ser. 2009;384(Suppl 2):33–46.

IUCN. Establishing Resilient Marine Protected Area Networks-making it happen. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Nature Conservancy. Washington: IUCN-WCPA; 2008.

Dudley N, Parish J. Closing the gap. Creating ecologically representative protected area systems: a guide to conducting the gap assessments of protected area systems for the convention on biological diversity. 2006. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Technical Series No. 24.

Gates S. Review of methodology of quantitative reviews using meta-analysis in ecology. J Ani Ecol. 2002;71:547–57.

Roberts PD, Stewart GB, Pullin AS. Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol Conserv. 2006;132:409–23.

Stewart GB, Cote IM, Kaiser MJ, Halpern BS, Lester SE, Bayliss HR, Mengersen K, Pullin AS. Are Marine Protected Areas effective tools for sustainable fisheries management? I. Biodiversity impact of marine reserves in temperate zones. In: Systematic Review No. 23. Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. 2008.

Bilotta GS, Alice MM, Boyd I. On the use of systematic reviews to inform environmental policies. Environ Sci Policy. 2014;42:67–77.

Guidetti P. The importance of experimental design in detecting the effects of protection measures on fish in Mediterranean MPAs. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshwat Ecosyst. 2002;12:619–34.

Lester SE, Halpern BS, Grorud-Colvert K, Lubchenco J, Ruttenberg BI, Gaines SD, Airame S, Warner RR. Biological effects within no-take marine reserves: a global analysis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2009;384:33–46.

Vandeperre F, Higgins RM, Sanchez-Meca J, Maynou F, Goni R, Martin-Sosa P, et al. Effects of no-take area size and age of marine protected areas on fisheries yields: a meta-analytical approach. Fish Fish. 2011;12:412–26.

Claudet J, Garcia-Charton JA, Lenfant P. Combined effects of level of protection and environmental variables at different spatial resolutions on fish assemblages in a Marine Protected Area. Conserv Biol. 2011;25(Suppl 1):105–14.

Sciberras M, Jenkins SR, Mant R, Kaiser MJ, Hawkins SJ, Pullin AS. Evaluating the relative conservation value of fully and partially protected marine areas. Fish Fish. 2013;16(Suppl 1):58–77.

Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE). Guidelines for systematic review and evidence synthesis in environmental management. 2013. Version 4.2. Environmental Evidence: [http://environmentalevidence.org/Documents/Guidelines/Guidelines4.2.pdf].

Woodcock P, Pullin AS, Kaiser MJ. Evaluating and improving the reliability of evidence syntheses in conservation and environmental science: a methodology. Biol Conserv. 2014;176:54–62.

Edwards P, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Roberts I, Wentz R. Identification of randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews: accuracy and reliability of screening records. Stat Med. 2002;21(Suppl 11):1635–40.

Stevens A, Milne R. The effectiveness revolution and public health. In: Scally G, editor. Progress in public health. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997. p. 197–225.

Pullin AS, Knight T. Time to build capacity for evidence synthesis in environmental management. Environ Evid. 2013;2(Suppl 1):21–2.

Pullin A, Stewart G. Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol. 2006;20:1647–56.

Sciberras M, Jenkins SR, Kaiser MJ, Hawkins SJ, Pullin AS. Evaluating the biological effectiveness of fully and partially protected marine areas. Environ Evid. 2013;2(Suppl 4):1–31.

García-Charton JA, Pérez-Ruzafa A. Ecological heterogeneity and the evaluation of the effects of marine reserves. Fish Res. 1999;42:1–20.

Edgar GJ, Bustamente RH, Farina JM, Calvopina M, Martinez C, Toral-Granda MV. Bias in evaluating the effects of marine protected areas: the importance of baseline data for the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Environ Conserv. 2004;31(Suppl 3):212–8.

Claudet J, Osenberg CW, Benedetti-Cecchi L, et al. Marine reserves: size and age do matter. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:481–9.

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. USA: Sage Publications; 2001.

Micheli F, Benedetti-Cecchi L, et al. Human impacts, Marine protected areas, and the structure of Mediterranean reef assemblages. Ecol Monogr. 2005;75(Suppl 1):81–103.

Authors’ contributions

MCM and GS conceived the study. MCM, BCO and GS make substantial contributions to study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation. MCM and BCO lead the writing. All authors contributed to writing the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Professor Andrew S. Pullin and Dr. Marija Sciberras for their commitment in providing feedbacks and inputs to this document. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewer for his insightful comments and constructive input. The first author was granted by a national post-doc contract partially funded by the Assessorato Regionale Territorio e Ambiente Dipartimento Regionale dell’Ambiente (PO FESR 2007-2013 Project—Action Line 3.2.1.2) Inventory of the Sicilian marine biodiversity—creation of a Regional Observatory of the Sicilian Biodiversity (ORBS) and development of monitoring techniques useful for species management and habitat protection.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mangano, M.C., O’Leary, B.C., Mirto, S. et al. The comparative biological effects of spatial management measures in protecting marine biodiversity: a systematic review protocol. Environ Evid 4, 21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-015-0047-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-015-0047-2