Abstract

Background

Pre-operative anaemia is associated with mortality and red blood cell (RBC) transfusion requirement after cardiac surgery. However, the effect on post-operative total morbidity burden (TMB) is unknown. We explored the effect of pre-operative anaemia on post-operative TMB.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Cardiac Post-Operative Morbidity Score (C-POMS) development study (n = 442). C-POMS describes and quantifies (0–13) TMB after cardiac surgery by noting the presence/absence of 13 morbidity domains on days 3 (D3), 5 (D5), 8 (D8) and 15 (D15). Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin concentration below 130 g/l for men and 120 g/l for women.

Results

Most patients were White British (86.1%) and male (79.2%) and underwent coronary artery bypass surgery (67.4%). Participants with pre-operative anaemia (n = 137, 31.5%) were over three times more likely to receive RBC transfusion (OR 3.08, 95%CI 1.88–5.06, p < 0.001), had greater D3 and D5 TMB (5 vs 3, p < 0.0001; 3 vs 2, p < 0.0001, respectively) and remained in hospital 2 days longer (8 vs 6 days, p < 0.0001) than non-anaemic patients. Transfused patients remained in hospital 5 days longer than non-transfused patients (p < 0.0001), had higher TMB on all days (all p < 0.001) and suffered greater pulmonary, renal, GI, neurological, endocrine and ambulation morbidities (p 0.026 to <0.001). Pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion were independently associated with increased C-POMS score.

Conclusions

Pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion are independently associated with increased post-operative TMB. Understanding TMB may assist in post-operative patient management to reduce morbidity. We recommend the use of the C-POMS tool as a standard outcome tool in further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anaemia, defined as circulating haemoglobin (Hb) concentration level below 130 g/l for men and 120 g/l for women (World Health Organization 2008), affects 24.8% of the global population (World Health Organization 2008), and up to 54.4% of cardiac surgery patients (Hung et al. 2011) are anaemic prior to surgery.

Since Hb is the circulation’s oxygen-carrying molecule, anaemia is associated with decreased blood oxygen content. Unless compensated for by increased blood flow, inadequate tissue oxygen delivery (Kurtz et al. 2010) may impair organ function. Furthermore, iron is not only essential for the synthesis of Hb’s haem moiety but also plays an important role in oxidative metabolism (Dunn et al. 2007). Iron deficiency may thus directly impair mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis through direct mitochondrial effects, as well as through anaemia and resulting impairment of oxygen delivery (Davies et al. 1982). In pre-operative anaemic patients, these deficits follow the patient into surgery, which itself is associated with a substantial and sustained increase in metabolic activity and hence in oxygen demand (Vallet and Futier 2010). By limiting the capacity to respond to this increased metabolic demand, pre-operative anaemia might thus be postulated to impair post-operative recovery.

Indeed, pre-operative anaemia has been associated with adverse outcome after cardiac surgery and has been associated with higher mortality (Hung et al. 2011; Zindrou et al. 2002; Cladellas et al.; van Straten et al. 2009; De Santo et al. 2009; Boening et al. 2011; Miceli et al. 2014), longer stay on the intensive care unit (ICU) (Hung et al. 2011; De Santo et al. 2009) and in hospital (Cladellas et al.; De Santo et al. 2009; Miceli et al. 2014; Kulier et al. 2007) and a higher incidence red blood cell (RBC) transfusion (De Santo et al. 2009; Boening et al. 2011). However, the evidence relating to the influence of pre-operative anaemia on post-operative morbidity is divided and only relates to specific outcomes, for example stroke (Cladellas et al.; Miceli et al. 2014; Fowler et al.) and renal dysfunction (Cladellas et al.; Miceli et al. 2014; Fowler et al.; Carrascal et al. 2010). Thus, whether anaemia is an independent risk factor for general morbidity after cardiac surgery (Fowler et al.) and the scale of this impact on total morbidity burden (TMB) has yet to be reported.

Thus, we explored the association between pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion requirement with TMB after cardiac surgery.

Methods

Participants

Patients were drawn from the Cardiac Post-Operative Morbidity Score (C-POMS) development and validation study; the methods describing how the C-POMS measurement tool was developed and validated are detailed elsewhere (Sanders et al.). In brief, patients undergoing any form of adult cardiac surgery (excluding cardiac surgery for a congenital heart condition or a cardiomyopathy) between January 2005 and November 2007 at the Heart Hospital, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, UK, and who gave written informed consent were eligible for inclusion. Excluded were those <18 years old, undergoing emergency surgery, who were enrolled in clinical intervention trials or who died within 5 days of surgery.

Defining anaemia

Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin (Hb) concentration below 130 g/l for men and 120g/l for women (Organisation WH 2008).

Outcome measurements

Post-operative morbidity and hence total morbidity burden were defined using the C-POMS tool (Table 1).

RBC transfusion

Allogenic RBC transfusions were defined as any RBC transfusion given to the participant in the intra- and post-operative period prior to discharge from hospital and were collected by staff using the C-POMS tool (Table 1).

At the time of data collection, there was no uniform protocol for blood transfusion, although the unit operated a generally restrictive transfusion policy. Trust guidelines stipulated that RBC transfusion was strongly indicated when the haemoglobin was below 70 g/l. Since November 1999, all allogeneic blood components produced in the UK have been subjected to leucocyte depletion (LD) whereby ≥99% of units have <5 × 106 leucocytes and >90% <1 × 106 leucocytes (Service UKBT and T 2007).

Total morbidity burden: C-POMS summary score

Post-operative morbidity was prospectively assessed on days 3 (D3), 5 (D5), 8 (D8) and 15 (D15) after cardiac surgery using the C-POMS tool (Sanders et al.). This represents TMB as a summary score (0–13), derived by noting the new or escalating presence or absence of 13 morbidity domains. Thus, the higher the score, the more morbidity experienced by the patient (Table 1).

Post-operative length of stay

Post-operative length of stay (LOS) was defined as the number of days from surgery (day of operation day 0) to discharge from hospital. This included any days spent in a receiving hospital following transfer from the operative hospital.

Other clinical data

Other clinical information including patient demographic details, relevant medical history, symptoms, risk factors, intra-operative details and general outcome variables (as shown in Table 2) were extracted from the C-POMS study. These were originally obtained from the medical and nursing records and the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgery of Great Britain and Ireland’s local database.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Stata version 13 (StataCorp Texas).

Baseline characteristics by anaemia were compared using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data. The association of transfusion with anaemia after adjustment for covariates (age, gender and EuroSCORE) was assessed using a logistic regression model, and the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were obtained. Associations with individual C-POMS morbidities were examined using random intercept logistic regression models. p values were corrected for multiple comparisons over the 13 morbidities using the Bonferroni correction.

Hb concentration at each time point was divided into quintiles, and differences in C-POMS score were tested between quintiles using Kruskal-Wallis test and a non-parametric test for trend across ordered groups (Cuzick 1985). Differences in C-POMS by quintile over all time points were estimated using a random intercept model with time fitted as a fixed effect.

Correlations of Hb with LOS and C-POMS score were assessed by Spearman rank correlation, and multivariate models were fitted for patient LOS and C-POMS score using ordinal logistic regression and random intercept models, respectively. Terms for both EuroSCORE and Hb were fitted as quintiles in the multivariate models as their distributions differed significantly from normality.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 748 potentially eligible patients undergoing cardiac surgery, 520 (69.5%) were screened (due to researcher availability) and 464 (89.2%) consented to participate. Fourteen participants subsequently became ineligible, leaving 450 who completed the study. Six participants declined for their data to be used outside the development of C-POMS, and a further two patients were without pre-operative Hb results, leaving 442 patients for analysis in this study.

Table 2 summarises the participants’ characteristics. Overall, the majority were White British (377, 86.1%) and male (350, 79.2%) with a mean age of 66.5 years (range 19 to 91 years). Seven patients (1.6%) were receiving renal dialysis while 50 (11.3%) had gastrointestinal disease. Most underwent isolated coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (298, 67.4%) and received cardiopulmonary bypass (410, 93.4%). Overall, the patients remained in the ICU and hospital for 2.0 and 11.8 days, respectively.

Pre-operative anaemia

The overall median Hb was 135 (range 79 to 173). Pre-operative anaemia was present in 31.5% (139/442) participants. The median Hb in the anaemic group was 116 (range 79 to 129 g/l) and 140 (range 120 to 173 g/l) in the non-anaemic groups (p = 0.000).

Table 2 shows the comparison of the pre-, intra- and post-operative characteristics between those with and without anaemia. Patients with pre-operative anaemia were older (69.5 vs 65.1 years, p = 0.000), less likely to be of White British ethnicity (76.8 vs 90.3%, p = 0.001) and more likely to be receiving pre-operative dialysis (4.3 vs 0.3%, p = 0.005) than non-anaemic participants. Those with anaemia were also more likely to have a history of cerebrovascular accident (6.5 vs 2.3%, p = 0.05), gastrointestinal (GI) disease (16.5 vs 8.9%, p = 0.023) or congestive heart failure (CHF) (6.2 vs 1.7%, p = 0.034) and to be diabetic (38.1 vs 16.5%, p = 0.000). Thus, as would be expected, anaemic patients had a higher EuroSCORE (5 vs 3, p = 0.000) and were more likely to be undergoing urgent (non-elective) surgery (47.5 vs 22.4%, p = 0.000). Furthermore, compared to non-anaemic patients, those with anaemia were more likely to return to theatre (9.6 vs 2.7%, p = 0.003), be readmitted to the ICU (8.4 vs 1.4%, p = 0.001) and so to stay longer in the ICU (3.0 vs 1.6 days, p = 0.000) and in hospital (15.2 vs 10.2 days, p = 0.000).

Pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion

Pre-operative anaemic patients were more likely to receive a RBC transfusion than non-anaemic patients (39.6 vs 14.5%, unadjusted odds ratio (OR) (95%CI) 3.85 (2.42–6.15) p < 0.0001) and, if transfused, to receive more units (2 vs 1 unit, p = 0.04). The association between anaemia and transfusion remained after adjustment for age, gender, EuroSCORE and LOS. Overall, anaemic patients had over three times the odds (OR 3.08, 95%CI 1.88–5.06, p < 0.001) of requiring a RBC transfusion than non-anaemic patients (14.1 vs 33.6%).

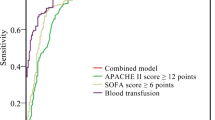

Patients who received a RBC transfusion remained in hospital 5 days longer than those who did not (LOS 11 vs 6 days, p < 0.0001) and had a significantly higher C-POMS score on all days (D3 5 vs 3, D5 3 vs 2, D8 4 vs 3, D15 4 vs 2, all p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, RBC transfusion was associated with pulmonary, renal, GI, neurological, endocrine and ambulation morbidities (p 0.026 to <0.001), independent of Hb (Table 3).

Pre-operative anaemia and C-POMS score

Pre-operative Hb was correlated with C-POMS score on D3 (rho −0.28, p < 0.0001) and D5 (rho −0.18, p = 0.0002) but not D8 (rho −0.143, p = 0.06) or D15 (rho −0.28, p = 0.06). Patients with pre-operative anaemia had a significantly higher C-POMS score on D3 and D5 than non-anaemic patients (5 vs 3 and 3 vs 2, respectively, both p < 0.0001) but not on D8 (3 vs 3, p = 0.32) or D15 (3.5 vs 3, p = 0.27) (Fig. 2). Pre-operative anaemia was associated with renal (p < 0.001) and assisted ambulation (p = 0.003) but no other C-POMS domains (Table 4).

Both pre-operative anaemia and transfusion requirement were independently associated with an increased C-POMS score (Table 5). Pre-operative anaemia was associated with a 0.55 (se 0.20) p = 0.005 increase in score, while RBC transfusion requirement was associated with an increase score of 1.23 (se 0.22) (p < 0.0001). If Hb replaced anaemia in this statistical model, both Hb and transfusion are independently associated with C-POMS score. C-POMS score decreases with every one quintile increase in Hb (B (se) −0.18 (0.06) p = 0.003) and increases by 1.19 with transfusion (se 0.22) (p < 0.0001). Increased age was also independently associated with increased C-POMS score in both models.

Pre-operative anaemia and hospital LOS

Pre-operative Hb was correlated with hospital LOS (rho −0.32, p < 0.00001). When compared to patients with Hb >14.6 (quintile 5), those with Hb <12.1 (quintile 1) had a higher morbidity score on D3 (5 vs 2, p < 0.0001) and D5 (3 vs 2, p = 0.007) and stayed in hospital for an additional 4 days (LOS 10 vs 6 days, p < 0.001) (Table 6). Pre-operative anaemic patients remained in hospital 2 days longer than non-anaemic patients (8 (inter-quartile range (IQR) 6–15) vs 6 (IQR 5–9) days, p < 0.0001, respectively).

Both pre-operative anaemia (OR 1.65, 95%CI 1.12–2.44, p = 0.01) and RBC transfusion requirement (OR 2.40, 95%CI 1.55–3.72, p < 0.001) were independently associated with increased hospital LOS (Table 7). If Hb level replaces pre-operative anaemia in the analysis model, there is a linear decrease in LOS over the five quintiles with odds ratios vs quintile 1 of 0.78, 0.64, 0.49 and 0.42 for quintiles 2 to 5. Lower Hb (OR per quintile of Hb 0.80, 95%CI 0.70–0.92, p = 0.001) and RBC transfusion requirement (OR 2.33, 95%CI 1.50–3.60, p = 0.0002) were independently associated with increased hospital LOS.

Discussion

Pre-operative anaemia has been associated with adverse outcome after cardiac surgery. However, whether anaemia is an independent risk factor for general morbidity after cardiac surgery (Fowler et al.) and the scale of this impact on total morbidity burden (TMB) has not previously been reported. Thus, our study explored the effect of pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion on total morbidity burden after cardiac surgery. Firstly, we found that compared to non-anaemic patients, pre-operative anaemic patients had significantly higher TMB (C-POMS scores) on D3 and D5, significantly more renal and ambulation morbidities and stayed in ICU and hospital an extra 1.4 days and an extra 2 days, respectively. As pre-operative anaemia was independently associated with increased TMB, reduction of post-operative morbidity might be achieved by treating pre-operative anaemia. Indeed, pre-operative optimization of anaemia in the UK is recommended (Service UKBT and T 2007; Department of Health 2007) as part of the patient blood management plan, with the use of intravenous (IV) iron if surgery may be delayed due to the time needed for oral iron to take effect (ERP Programme 2010). However, although IV iron therapy for anaemia has been shown to effectively treat anaemia in medical (Usmanov et al. 2008), and non-cardiac pre-operative settings (Munoz et al. 2009), the effect on cardiac surgical patients is not yet confirmed due to the low level of evidence available (Hogan et al. 2015). Thus, further prospective evidence in cardiac surgery patients is required before any recommendation for the use of IV iron to treat pre-operative anaemia in these patients can be made. Secondly, blood is a limited resource and is associated with high transfusion costs (Department of Health 2007), administration incidents and risks (Group SS 2014) and specifically poorer outcome in cardiac surgical patients (Galas et al. 2013). Our results found RBC transfusion to be independently associated with TMB, and patients spent an extra 5 days in hospital. Thus, strategies to reduce RBC use may reduce transfusion errors, reduce healthcare costs and improve patient well-being. However, although there are considerable differences in transfusion triggers across UK cardiac surgery centres (Murphy et al. 2013), restrictive transfusion protocols (Ternström et al. 2014) and patient blood management systems (Gross et al. 2015) do not appear to reduce post-operative morbidity in all instances, with the TITRe2 trial suggesting liberal transfusion may actually be superior after cardiac surgery (Murphy et al. 2015). This again raises the question on whether it is anaemia or RBC transfusion that carries the greatest risk (Vincent 2015; Du Pont-Thibodeau et al. 2014), and hence, exploring TMB in future anaemia and transfusion studies in cardiac surgery is needed. Adding further complexity to our understanding of pre-operative anaemia, treatment strategies and outcome, hepcidin, the principal regulator of systemic iron homeostasis, has been found to be an independent risk factor for poor outcome (Hung et al. 2015). This provides a new variable for consideration in further work, which is much needed before any conclusions can be made.

Where evidence exists, our study is comparable to other studies in terms of incidence of anaemia (De Santo et al. 2009; Kulier et al. 2007) and medical history (De Santo et al. 2009; Kulier et al. 2007). Our results were also consistent with others identifying pre-operative anaemia as a risk factor for post-operative renal complications (Cladellas et al.; Miceli et al. 2014; Fowler et al.) but not for cardiovascular complications (Cladellas et al.; Miceli et al. 2014; Fowler et al.; Carrascal et al. 2010). However, our findings did not suggest pre-operative anaemia to be associated with stroke (Miceli et al. 2014; Fowler et al.), infection (Cladellas et al.; Fowler et al.) or respiratory failure (Carrascal et al. 2010) as has been found previously. This is likely to be due to difference in definitions used between the studies, and thus the use of a standardised framework, like C-POMS, is advocated for future morbidity outcome after cardiac surgery studies.

There are four main limitations with our study. Firstly, pre-operative baseline characteristics obtained from the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgery of Great Britain and Ireland local database were 93.9% complete. It is possible the small amount of missing data may have had an influence on comparisons on the baseline characteristics. Secondly, although C-POMS is a validated tool for the description and quantification of morbidity after cardiac surgery (Sanders et al.), there are limitations to its use (Sanders et al.). This includes transient morbidities which may be missed on non-data collection days and that fluctuations cannot be tracked. Thirdly, as it is recommended that treatment of pre-operative anaemia should rely on the diagnosis of the type of anaemia, identifying the underlying cause or disease (Weiss and Goodnough 2005), we had intended to explore outcome by type of anaemia. However, since only 1.4% (2/139) of anaemic patients in our study had pre-operative haematinic profiles available, this was not feasible. Finally, we cannot prove that the associations we report are causal. Investigating this issue will require interventional studies to mitigate against pre-operative anaemia and post-operative transfusion, and we would advocate for such trials to take place.

Conclusions

In conclusion, while previous evidence is inconclusive on the effect of pre-operative anaemia-specific morbidity outcome (for example stroke and renal dysfunction) after cardiac surgery, our study suggests that pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion use are independently associated with significant overall total morbidity burden following cardiac surgery. Thus, strategies to reduce pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion need are important. However, understanding that TMB (at the level of detail that the C-POMS tool permits) associated with pre-operative anaemia and RBC transfusion may assist in post-operative patient management to reduce morbidity, especially if it is not possible to ascertain whether it is anaemia or RBC transfusion that carries the greatest risk to patient well-being and recovery. We would recommend the use of the C-POMS tool as a standard morbidity outcome measurement tool in further studies to explore this and whether interventions implemented to reduce post-operative morbidity burden actually do reduce TMB as measured using the C-POMS tool.

Abbreviations

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- AVR:

-

Aortic valve replacement

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass graft

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- C-POMS:

-

Cardiac Post-Operative Morbidity Score

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- D3 (D5, D8, D15):

-

Day 3 (day 5, day 8, day 15)

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- Hb:

-

Haemoglobin

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- INR:

-

International normalised ratio

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- LD:

-

Leucocyte depletion

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MVR:

-

Mitral valve replacement

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- OPA:

-

Out-patient appointment

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OT:

-

Occupational therapy

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- TMB:

-

Total morbidity burden

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Boening A, Boedeker R-H, Scheibelhut C, Rietzschel J, Roth P, Schönburg M. Anemia before coronary artery bypass surgery as additional risk factor increases the perioperative risk. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:805–10.

Carrascal Y, Maroto L, Rey J, Arevalo A, Arroyo J, Echevarria JR, Arce N, Fulquet E. Impact of preoperative anemia on cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:249–255.

Cladellas M, Bruguera J, Comin J, Vila J, de JE, Marti J, Gomez M. Is pre-operative anaemia a risk marker for in-hospital mortality and morbidity after valve replacement? Eur Heart J. 2006;(27):1093–1099.

Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4:87–90.

Davies KJ, Maguire JJ, Brooks GA, Dallman PR, Packer L. Muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics, oxygen supply, and work capacity during dietary iron deficiency and repletion. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:E418–E427.

Department of Health: Better Blood Transfusion. Safe and Appropriate Use of Blood. Volume HSC 2007/0. London: Department of Health; 2007.

De Santo L, Romano G, Della Corte A, de Simone V, Grimaldi F, Cotrufo M, de Feo M. Preoperative anemia in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting predicts acute kidney injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:965–70.

Du Pont-Thibodeau G, Harrington K, Lacroix J. Anemia and red blood cell transfusion in critically ill cardiac patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2014;4:16.

Dunn LL, Suryo RY, Richardson DR. Iron uptake and metabolism in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:93–100.

ERP Programme. Delivering enhanced recovery. Helping patients to get better sooner after surgery. Department of Health; 2010. Archived and accessible via http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_115156.pdf.

Fowler AJ, Ahmad T, Phull MK, Allard S, Gillies MA, Pearse RM. Meta-analysis of the association between preoperative anaemia and mortality after surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1314–1324.

Galas FR, Almeida JP, Fukushima JT, Osawa EA, Nakamura RE, Silva CM, de Almeida EP, Auler Jr. JO, Vincent JL, Hajjar LA. Blood transfusion in cardiac surgery is a risk factor for increased hospital length of stay in adult patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:54.

Gross I, Seifert B, Hofmann A, Spahn DR. Patient blood management in cardiac surgery results in fewer transfusions and better outcome. Transfusion. 2015;55:1075–81.

Group SS. Annual Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) Report 2014. 2014.

Hogan M, Klein AA, Richards T. The impact of anaemia and intravenous iron replacement therapy on outcomes in cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:218–226.

Hung M, Besser M, Sharples LD, Nair SK, Klein AA. The prevalence and association with transfusion, intensive care unit stay and mortality of pre-operative anaemia in a cohort of cardiac surgery patients. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:812–818.

Hung M, Ortmann E, Besser M, Martin-Cabrera P, Richards T, Ghosh M, Bottrill F, Collier T, Klein AA. A prospective observational cohort study to identify the causes of anaemia and association with outcome in cardiac surgical patients. Heart. 2015;101:107–112.

Kulier A, Levin J, Moser R, Rumpold-Seitlinger G, Tudor IC, Snyder-Ramos SA, Moehnle P, Mangano DT. Impact of preoperative anemia on outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:471–9.

Kurtz P, Schmidt JM, Claassen J, Carrera E, Fernandez L, Helbok R, Presciutti M, Stuart RM, Connolly ES, Badjatia N, Mayer SA, Lee K. Anemia is associated with metabolic distress and brain tissue hypoxia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:10–16.

Miceli A, Romeo F, Glauber M, de Siena PM, Caputo M, Angelini GD. Preoperative anemia increases mortality and postoperative morbidity after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:137.

Munoz M, Garcia-Erce JA, Diez-Lobo AI, Campos A, Sebastianes C, Bisbe E. Usefulness of the administration of intravenous iron sucrose for the correction of preoperative anemia in major surgery patients. Med Clin (Barc). 2009;132:303–306.

Murphy M, Murphy G, Gill R, Herbertson M, Allard S, Grant-Casey J. National comparative audit of blood transfusion: 2011 audit of blood transfusion in adult cardiac surgery. Available at http://hospital.blood.co.uk/audits/national-comparative-audit/national-comparative-audit-reports/.

Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, Wordsworth S, Stokes EA, Angelini GD, Reeves BC, TITRe2 Investigators. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:997–1008.

Sanders J, Keogh BE, Van der Meulen J, Browne JP, Treasure T, Mythen MG, Montgomery HE. The development of a postoperative morbidity score to assess total morbidity burden after cardiac surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:423–433.

Service UKBT and T. Guidelines for the blood transfusion services in the UK. 7th ed. 2007.

Ternström L, Hyllner M, Backlund E, Schersten H, Jeppsson A. A structured blood conservation programme reduces transfusions and costs in cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19:788–94.

Usmanov RI, Zueva EB, Silverberg DS, Shaked M. Intravenous iron without erythropoietin for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with moderate to severe congestive heart failure and chronic kidney insufficiency. J Nephrol. 2008;21:236–242.

Vallet B, Futier E. Perioperative oxygen therapy and oxygen utilization. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:359–364.

van Straten AH, Hamad MA, van Zundert AJ, Martens EJ, Schonberger JP, de Wolf AM. Preoperative hemoglobin level as a predictor of survival after coronary artery bypass grafting: a comparison with the matched general population. Circulation. 2009;120:118–125.

Vincent J-L. Which carries the biggest risk: anaemia or blood transfusion? Transfus Clin Biol J la Société Fr Transfus Sang. 2015;22:148–50.

Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011–1023.

World Health Organization. Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993–2005. WHO Global Database on Anaemia. 2008.

Zindrou D, Taylor KM, Bagger JP. Preoperative haemoglobin concentration and mortality rate after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2002;359:1747–1748.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the protocol development group (PDG) and to the patients who generously gave their time and consent to participate in the C-POMS study.

Funding

This work was unfunded, but Professors Hugh Montgomery and Michael Mythen were supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Availability of data and materials

Informed consent was not obtained for publication of patient data as publication of the dataset was not anticipated at the time of the initial C-POMS study. Thus, the data that support the findings of this study are available from JS but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of an appropriate research ethics committee and information governance (where appropriate) approvals.

Authors’ contributions

Each author has fulfilled the ICMJE guidelines to qualify as an author. According to the ICMJE guidelines, to qualify as an author, one should have (1) made substantial contributions to the conception and design (JS, DF, HM), acquisition of data (JS, SB, US), or analysis (JC) and interpretation of data (JS, DF, HM, MM); (2) been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content (ALL), and (3) given final approval of the version to be published (ALL). Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not included.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The National Research Ethics Committee London-Bentham (Chair Professor David Katz) gave ethics permission for this work exploring pre-operative anaemia and RBC use in the Cardiac Post-Operative Morbidity Score (C-POMS) study (protocol amendment 7) on 6 September 2011 (reference 04/Q0502/73). All patients included in this study gave written informed consent to participate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, J., Cooper, J.A., Farrar, D. et al. Pre-operative anaemia is associated with total morbidity burden on days 3 and 5 after cardiac surgery: a cohort study. Perioper Med 6, 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-017-0057-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-017-0057-4