Abstract

Background

While patient-reported treatment dissatisfaction is considered an important factor in determining the success of substance use disorder treatment, the levels of dissatisfaction with opioid agonist therapies (OAT) and its relationship with the risk of fentanyl exposure have not been characterized in the context of the ongoing opioid overdose crisis in the US and Canada. Our primary hypothesis was that OAT dissatisfaction was associated with an increased odds of fentanyl exposure.

Methods

Our objective was to examine self-reported treatment satisfaction among OAT patients in Vancouver, Canada and the association with fentanyl exposure. Longitudinal data were derived from 804 participants on OAT enrolled in two community-recruited harmonized prospective cohort studies of people who use drugs in Vancouver between 2016 and 2018 via semi-annual interviews and urine drug screens (UDS). We employed multivariable generalized estimating equations to examine the relationship between OAT dissatisfaction and fentanyl exposure.

Results

Out of 804 participants (57.0% male), 222 (27.6%) reported being dissatisfied with OAT at baseline and 1070 out of 1930 observations (55.4%) had fentanyl exposure. The distribution of OAT reported in the sample was methadone (n = 692, 77.7%), buprenorphine-naloxone (n = 82, 9.2%), injectable OAT (i.e., diacetylmorphine or hydromorphone; (n = 65, 7.3%), slow-release oral morphine (n = 44, 4.9%) and other/study medication (n = 8, 1.0%). In the multivariable analysis, OAT dissatisfaction was positively associated with fentanyl exposure (AOR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.08–1.66).

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of OAT patients in our sample reported dissatisfaction with their OAT, and more than half were exposed to fentanyl. We also found that those who were dissatisfied with their OAT were more likely to be exposed to fentanyl. These findings demonstrate the importance of optimizing OAT satisfaction in the context of the ongoing opioid overdose crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States and Canada are facing an overdose crisis that is being driven in large part by the introduction of illicitly-manufactured fentanyl and its analogues into the illicit drug supply [1]. In the United States, the rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone, such as fentanyl and its analogs, has increased 33-fold from 0.3 deaths per 100,000 population in 1990 to 9.9 in 2018 [2]. In British Columbia, Canada between 2015 and 2017, fentanyl was detected in 79% of overdose deaths [3].

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) with methadone, buprenorphine and other long-acting opioids are a vital treatment for opioid use disorder and have been shown to be superior to withdrawal management in treatment retention and reduction of opioid use, morbidity and all-cause mortality [4,5,6,7,8]. In British Columbia, methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone are considered first line OAT treatments with slow release oral morphine as an alternative, and injectable opioid agonist therapy (iOAT) with hydromorphone or diacetylmorphine as an intensive treatment option [9]. Despite the recent scale up of OAT programs, the provincial rate of paramedic attended overdoses has increased four-fold from January 2015 to March 2019, three years after the 2016 declaration of a public health emergency secondary to the opioid overdose crisis [1].

Previous studies have suggested that a patient’s perceived treatment satisfaction is a key determinant of the success of the OAT. For example, patients who were dissatisfied with OAT have been shown to be more likely to report increased side effects and continued illicit substance use [10,11,12]. Conversely, satisfaction with OAT has been associated with significantly higher treatment retention rates, reduced drug use at one year follow up and perceived improvement in social, physical and emotional well-being [13,14,15,16]. The existing literature evaluating patient satisfaction with OAT suggests that satisfaction may be improved by reducing programmatic demands, addressing social and medical needs, reducing stigma experienced by people on OAT, expanding access for different OAT options and implementing models of service delivery that incorporate patient-centered approaches [17]. The World Health Organization (WHO) also advises to assess treatment satisfaction for patients who are receiving treatment for substance use disorder [18]. However, in the context of the ongoing opioid overdose crisis, we are unaware of any study that has examined the role of treatment satisfaction and overdose risk among OAT patients.

Given the recent increase of fentanyl in the illicit drug supply and resulting elevated risk of overdose, it is important to understand the levels of satisfaction among individuals on OAT and whether treatment satisfaction is associated with treatment retention and the risk of fentanyl exposure. Therefore, we sought to examine self-reported treatment dissatisfaction among OAT patients in Vancouver, Canada. This study had three hypotheses: (1) Dissatisfaction with OAT will be associated with the increased odds of discontinuation of OAT; (2) Discontinuation of OAT will be associated with increased odds of fentanyl exposure; and (3) Among those retained on OAT, OAT dissatisfaction will be associated with the increased odds of fentanyl exposure. We also tested all hypotheses restricting to patients on methadone specifically as the majority of the OAT patients in our study setting were on methadone at the time of the study in 2016–2018 [1].

Methods

The Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS) are active open prospective cohort studies of adults who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. These cohorts have been described in detail in past studies [19, 20]. In brief, participants have been recruited through referrals, word of mouth and street outreach primarily in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver, which is characterized by high rates of illicit drug use [21]. VIDUS enrolls HIV-negative persons who report injecting an illicit drug at least once and ACCESS enrolls HIV-positive individuals who report using an illicit drug (not including cannabis, which was illegal during almost all of the study period) in the month preceding enrollment. Other eligibility criteria include being aged 18 years or older, residing in the greater Vancouver region and providing written informed consent in both cohorts. The study instruments and follow-up procedures for each study are harmonized to permit combined analyses. At baseline and semi-annually thereafter, participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire obtaining socio-demographic data as well as information pertaining to drug use patterns, risk behaviours, and health care utilization. They also are administered a multi-panel qualitative urine drug screen (UDS), BTNX Rapid Response™ Multi-Drug Test Panel (Markham, ON, Canada) at each study visit. Participants receive a $40 (CDN) honorarium for each study visit. The University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board provided ethical approval for both studies.

The question about OAT satisfaction was added to the questionnaire in December 2016. Therefore, for the present study, we used data collected between December 2016 and November 2018. The observations were restricted to those with reports of being enrolled in any OAT at some point in the past six months for testing Hypotheses 1 and 2. For Hypothesis 3, we further restricted the observations to those with reports of being currently enrolled in any OAT. A sub analysis was performed for all three hypotheses by restricting OAT type to methadone.

The primary outcome for the Hypothesis 1 was discontinuation of OAT in the past six months (yes vs. no), defined as being enrolled in OAT at some point during the past six months, but not being enrolled in any OAT at the time of the interview. The primary outcome in Hypothesis 2 and 3 was fentanyl exposure, defined as a positive UDS result for fentanyl at the time of the interview. Fentanyl positive UDS was selected as an objective marker of overdose risk. Fentanyl has contaminated the illicit drug supply to a great extent in our study setting and has been the principal driver of the opioid overdose crisis [1]. Illicit fentanyl is also detected in non-opioid drugs [1, 3]; therefore, we decided to use fentanyl positive UDS as a more objective marker of overdose risk. The cut-off value of the calibrator for fentanyl positive screens is 100 ng/mL of fentanyl or 20 ng/mL of norfentanyl, and is believed to detect exposure to fentanyl within a maximum of past three days [22].

The primary explanatory variable of interest in Hypotheses 1 and 3 was dissatisfaction with OAT as measured during the interview by asking “Overall, how satisfied were you with the medication treatment you received?”. A five-point scale was used including the following selections “very unsatisfied,” “unsatisfied,” “neutral,” “satisfied” and “very satisfied”. We dichotomized the variable as: “very unsatisfied” or “unsatisfied” vs. “neutral”, “satisfied” or “very satisfied”. The primary explanatory variable for hypothesis 2 was discontinuation of OAT in the past six months (yes vs. no).”

For all hypotheses, we also considered secondary explanatory variables that might confound the primary exposure-outcome relationships based on our clinical experience and previous research [23]. These included socio-demographic characteristics, including: age (per year older); self-identified gender (male vs. non-male); ancestry (white vs. non-white); and homelessness in the past 6 months. Drug-use variables referred to behaviours in the previous 6 months, and included: stimulant use (i.e., cocaine, crack or crystal methamphetamine use; ≥ daily vs. < daily) and injection drug use. We also included the most recent OAT medication type (methadone vs. other). Further, any illicit opioid use (≥ daily vs. < daily) was included in the descriptive analyses, but not in the multivariable analysis because we hypothesized that it would mediate the relationship between OAT dissatisfaction and fentanyl exposure given the high levels of contamination of illicit opioids with fentanyl in our setting.

First, we compared the baseline sample characteristics between those with and without fentanyl exposure, using the Pearson’s Chi-squared test (for binary variables) and Wilcoxon Rank Sum test (for continuous variables).

In order to test all hypotheses, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with logit link, which provided standard errors adjusted by multiple observations per person using an exchangeable correlation structure. For all three hypotheses, we fit a multivariable GEE model by including the primary explanatory variable and all secondary explanatory variables that were associated with the respective outcomes for each hypothesis in unadjusted analyses at p < 0.10. All p-values were two-sided and tests were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

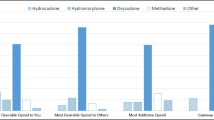

In total, 804 participants were eligible for the present analyses. The median age at baseline of this sample was 47.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 37.9–54.6), 458 (57.0%) were male and 362 (45.0%) self-reported white ancestry. Overall, the 804 individuals contributed 1930 observations and the median number of follow-up visits was 2 (IQR: 1–4) per person. The baseline characteristics of all participants stratified by fentanyl exposure are presented in Table 1. Across the 804 particiapnts included in the study at baseline, 131 (16.3%) felt very satisfied, 311 (38.7%) felt satisfied, 140 (17.4%) were neutral, 120 (14.9%) felt unsatisfied and 102 (12.7%) felt very unsatisfied with OAT. In terms of the types of the OAT medications that participants were on at baseline, methadone was the most commonly reported medication (n = 692, 77.7%), followed by buprenorphine-naloxone (n = 82, 9.2%), iOAT (i.e., diacetylmorphine or hydromorphone; (n = 65, 7.3%), slow-release oral morphine (n = 44, 4.9%), other/study medication (n = 8, 1.0%). Distributions of OAT satisfaction scores across the four different OAT medication types are depicted in Fig. 1. The breakdown for dissatisfaction among the range of OAT types included in the sample at baseline was: methadone 30.8% (n = 627), buprenorphine 19.1% (n = 68), oral morphine 20.9% (n = 43), and iOAT 11.9% (n = 59).

Of the 1930 observations, 180 (9.3%) reported discontinuation of OAT in the past six months. Among 599 participants who injected drugs in the past six months at baseline, 79 (13.2%) injected illicit opioids only, 129 (21.5%) injected drugs other than illicit opioids (e.g., stimulants), and 391 (65.3%) injected both illicit opioids and other drugs. In total, 1070 (55.4%) observations had a positive UDS result for fentanyl at the time of the interview.

In the multivariable GEE analysis to test Hypothesis 1, OAT dissatisfaction was significantly associated with discontinuation of OAT (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.72; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.66–5.21) after adjusting for age, homelessness, daily stimulant use and injection drug use. This association was consistent when OAT was restricted to methadone only (AOR = 3.59; 95% CI: 2.49–5.18). In the multivariable GEE analysis to test Hypothesis 2, OAT discontinuation was significantly associated with fentanyl exposure (AOR = 2.05; 95% CI: 1.47–2.84) after adjusting for age, homelessness, daily stimulant use and injection drug use. Again, this association was consistent when OAT was restricted to methadone only (AOR = 2.20; 95% CI: 1.50–3.21).

The results of the bivariable and multivariable GEE analyses for Hypothesis 3 are presented in Table 2. As shown, in the final multivariable model after adjusting for age, homelessness and injection drug use, dissatisfaction with OAT remained independently and positively associated with fentanyl exposure (AOR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.08–1.66). This association was consistent when OAT type was restricted to methadone (AOR = 1.47; 95% CI: 1.16–1.87).

Discussion

In our sample of participants on OAT, 27.6% reported OAT dissatisfaction at baseline and 9.3% of observations included reports of OAT discontinuation in the past six months. The prevalence of fentanyl exposure in all observations was also substantial at 55%. We found that individuals who were dissatisfied with their OAT were more likely to have discontinued the OAT, and OAT discontinuation was positively associated with fentanyl exposure. The relationship between OAT dissatisfaction and fentanyl exposure persisted even when the analysis was restricted to those who were retained on OAT, and after adjusting for potential confounders. These findings also remained consistent when we restricted the analyses to participants on methadone only.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrated the relationship between patient-reported OAT dissatisfaction and fentanyl exposure. Our findings indicate that ensuring treatment satisfaction among OAT patients could potentially prevent exposure to fentanyl and reduce the subsequent risk of overdose. The baseline prevalence of OAT dissatisfaction in our study (27.6%) was higher than what has been reported in past literature, with estimates ranging from 8.1 to 20.6% [11, 24, 25]. This could be due to the high rates of potent opioids such as fentanyl and its analogues in the illicit drug supply in our study setting, making it more challenging to stabilize patients on OAT [3, 9]. Another potential significant contributor to dissatisfaction is the regulatory change in British Columbia introduced in 2014 to the Methadone Maintenance Program, which involved changing the methadone formulation [26]. Previous studies reported significant increases in the prevalence of heroin injection and opioid withdrawal symptoms following this regulatory change in our setting [27, 28].

Past literature has shown a range of factors that could be associated with OAT dissatisfaction, including frequent use of heroin or cocaine, not feeling respected by OAT clinic staff, inadequate methadone doses, increased side effects and unmet service needs (such as employment, housing and finances) [11, 12, 16, 23, 25, 29]. Care providers should explore OAT satisfaction with their patients and practice patient-centered decision making in order to improve satisfaction. As the literature suggests, satisfaction with OAT may be improved by reducing programmatic demands (e.g. allowing for telephone visits, longer prescriptions and carry doses where appropriate) as well as addressing people’s social and medical needs to ensure overall wellbeing [17]. Additionally, access should be improved for different OAT options (i.e. sustained release oral morphine, iOAT) and different models of service delivery that incorporate patient-centered approaches.

An important focus for future study should be looking at the unique clinical considerations that apply in the case of fentanyl exposed compared to non-exposed individuals with opioid use disorder. Learning more about fentanyl exposure is crucial given that OAT is key for overdose prevention and fentanyl is a main driver of the overdose crisis in the US and Canada [1, 2]. Further to this, the factors which improve retention on OAT should be evaluated as a part of the strategy to address the overdose crisis.

There are several limitations in this study. Given this study was observational, we cannot infer causation between OAT dissatisfaction and exposure to fentanyl. Further to this, our analysis cannot establish the temporality between the exposure and outcome, and therefore there is a potential that the observed association may mean that fentanyl exposure resulted in low satisfaction. As with any observational research, unmeasured confounders could exist; however, we tried to reduce this bias through adjustment of regression models using potential predictors of having a UDS positive for fentanyl. Additionally, as the VIDUS and ACCESS cohorts are not random samples, generalizability of the findings could be limited. Part of the data used in the study was self-reported and therefore could be subject to reporting biases, however self-reported behavioural data has been shown to be generally accurate among adult drug-using populations [30]. Also, due to the small sample size, we were unable to stratify the analyses by all four OAT medication types. There could potentially be differences in the results by OAT medication types. Lastly, the lack of multidimensionality in the OAT satisfaction scoring, due to limitations in survey length, makes it impossible to discern what it is that is causing individuals to be dissatisfied. Future research should explore this topic through a qualitative study design.

Conclusion

Among our sample of participants on OAT in Vancouver, Canada, 27.6% were dissatisfied with their OAT, 9.3% discontinued their OAT in the last six months and over half had a UDS positive for fentanyl. We found that OAT dissatisfaction remained independently associated with fentanyl exposure after adjusting for potential confounders. Given the current opioid overdose crisis in the United States and Canada and the risk of overdose and death with ongoing illicit opioid use, these findings demonstrate the importance of optimizing patient satisfaction with their OAT in order to potentially reduce exposure to fentanyl [2, 31].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the highly criminalized and stigmatized nature of the study population but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OAT:

-

Opioid agonist therapy

- iOAT:

-

Injectable opioid agonist therapy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- VIDUS:

-

Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study

- ACCESS:

-

AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services

- UDS:

-

Urine drug screen

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equations

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

References

BC Centre for Disease Control. Overdose response indicator report. 2020. www.bccdc.ca.

Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018 key findings data from the National Vital Statistics System, Mortality. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

BC Centre for Disease Control. Prescription history and toxicology findings among people who died of an illicit drug overdose in BC, 2015–2017. 2019.

Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1550.

British Columbia Centre on Substance Use and B.C. Ministry of Health. A guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder; 2017.

Hser Y-I, Evans E, Huang D, et al. Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2016;111(4):695–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13238.

Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, Chaisson CE, Mcpheeters JT, Crown WH. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137–45. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3107.

BC Centre on Substance Use. Guidance for injectable opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder; 2017.

Alcaraz S, Trujols J, Siñol Llosa N, Duran-Sindreu S, Batlle F, de Los Perez, Cobos J. Exploring predictors of response to methadone maintenance treatment for heroin addiction: the role of patient satisfaction with methadone as a medication. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2017;19(4):35–40.

Muller AE, Bjørnestad R, Clausen T. Dissatisfaction with opioid maintenance treatment partly explains reported side effects of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187(February):22–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.018.

De Los Cobos JP, Trujols J, Siñol N, Duran-Sindreu S, Batlle F. Satisfaction with methadone among heroin-dependent patients with current substance use disorders during methadone maintenance treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(2):157–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000463.

Villafranca SW, McKellar JD, Trafton JA, Humphreys K. Predictors of retention in methadone programs: a signal detection analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(3):218–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.020.

Perreault M, White ND, Fabrès É, Landry M, Anestin AS, Rabouin D. Relationship between perceived improvement and treatment satisfaction among clients of a methadone maintenance program. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33(4):410–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.12.003.

Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Brown BS, Mitchell SG, Schwartz RP. The role of patient satisfaction in methadone treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(3):150–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952991003736371.

Zhang Z, Gerstein DR, Friedmann PD. Patient satisfaction and sustained outcomes of drug abuse treatment. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(3):388–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307088142.

Reist D. Methadone maintenance treatment in British Columbia, 1996–2008: analysis and recommendations. Victoria. 2010;(May):1996–2008.

Park DA. World Health Organization client satisfaction evaluation. 2000. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/j022v08n02_02

Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PGA, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280(6):547–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.6.547.

Wood E, Kerr T. What do you do when you hit rock bottom? Responding to drugs in the city of Vancouver. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.12.007.

Campbell, Larry Boyd, Neil Culbert L. A thousand dreams. 2009.

Silverstein JH, Rieders MF, McMullin M, Schulman S, Zahl K. An analysis of the duration of fentanyl and its metabolites in urine and saliva. Anesth Analg. 1993;76(3):618–21. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199303000-00030.

Marchand K, Palis H, Peng D, et al. The role of gender in factors associated with addiction treatment satisfaction among long-term opioid users. Employ Assist Q. 2015;9(5):391–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000145.

Alcaraz S, Viladrich C, Trujols J, Siñol N, Cobos JP. Heroin-dependent patient satisfaction with methadone as a medication influences satisfaction with basic interventions delivered by staff to implement methadone maintenance treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1203–11. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S164181.

Aziz Z, Ph D, Chong NJ, Sc MM. Journal of substance abuse treatment a satisfaction survey of opioid-dependent patients with methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:47–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.008.

College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Updates from the methadone maintenance program. https://www.cpsbc.ca/for-physicians/college-connector/2013-V01-03/07. Accessed 10 Oct 2020.

Socías ME, Wood E, McNeil R, et al. Unintended impacts of regulatory changes to British Columbia Methadone Maintenance Program on addiction and HIV-related outcomes: Aan interrupted time series analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;45:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.03.008.

McNeil R, Kerr T, Anderson S, et al. Negotiating structural vulnerability following regulatory changes to a provincial methadone program in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:168–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.008.

Barmada H, Patil D, Roberts S, Colon-Rivera H, Chang G. Perceived stigma and satisfaction with care among veterans receiving methadone maintenance treatment: a pilot study. Addict Disord Treat. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADT.0000000000000112.

Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(3):253–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National Report: Opioid-Related Harms in Canada Web-Based Report. Ottawa; 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01DA038886, R01DA021525). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canadian Research Initiative on Substance Misuse (SMN–139148). The work of LM is funded through the BCCSU International Collaborative Addiction Medicine Research Fellowship (NIH Grant R25-DA037756). KH holds the St. Paul’s Hospital Chair in Substance Use Research and is supported in part by the NIH grant (U01DA038886), a CIHR New Investigator Award (MSH-141971), a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Scholar Award, and the St. Paul’s Foundation. NF is supported by a MSFHR/St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation Scholar Award. M-JM is supported in part by the United States NIH (U01-DA0251525), a Scholar Award from MSFHR, and a New Investigator award from CIHR. He is the Canopy Growth professor of cannabis science at the University of British Columbia, a position established through arms’ length gifts to the university from Canopy Growth, a licensed producer of cannabis, and the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

Funding

US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01DA021525, U01DA038886, U01-DA0251525). Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canadian Research Initiative on Substance Misuse (SMN–139148). CIHR New Investigator Award (MSH-141971). International Collaborative Addiction Medicine Research Fellowship (NIH Grant R25-DA037756). Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). St. Paul’s Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LM and KH conceived this study. LM prepared the first draft manuscript with significant support and guidance from KH in writing, data analysis and results interpretation. CG provided statistical data analysis. TK, NF and MM reviewed and offered manuscript comments, edits and assisted in the interpretation of the results. TK, MM and KH led and managed the parent cohort studies. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

University of British Columbia and Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board provided ethical approval. All participants provided informed consent prior to cohort study enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no relevant disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackay, L., Kerr, T., Fairbairn, N. et al. The relationship between opioid agonist therapy satisfaction and fentanyl exposure in a Canadian setting. Addict Sci Clin Pract 16, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00234-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00234-w