Abstract

Background

Tree regeneration is a key component of resilience because it promotes post-disturbance recovery of forests. Northwestern Patagonia from Argentina is occupied by Nothofagus alpina (Na), N. obliqua (No), and N. dombeyi (Nd) forests that grow along an intense precipitation gradient, managed throughout shelterwood silvicultural system by technicians of the Lanin Natural Reserve. The objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of seeding cuttings over the dynamics of Nothofagus mixed forests across landscape (precipitation gradient) based mainly on the composition and abundance of tree regeneration, permanent sampling plots and generalized linear mixed models. In particular, we analysed: (i) the structure of sexual and asexual regeneration during < 10, 10–20 and > 20 years after harvest (the dynamics of managed forests), and (ii) the structure of sexual regeneration in primary and managed forests after > 20 years of harvest (the effect of silviculture).

Results

Nd was the most abundant species in the regeneration of managed forests during all periods in both sites despite its lower contribution to the adult cohort. During the 10–20 years period after harvest, the humid site exhibited higher regeneration density than the mesic site (120,000 and 6000 ind ha−1, respectively), and it decreased afterwards. The number of established regeneration (> 2 m height) was lower for Na in the mesic site and for No in the humid site (0 and 57 ind ha−1, respectively). However, in comparison to No, Na showed a higher number of sprouted stumps and sprouts per stump, and a higher sprout height in the mesic site. No exhibited higher sprout mortality in the humid site. Finally, the regeneration of primary forests showed lower density and height, and a more balanced composition than that of managed forests.

Conclusions

The silvicultural effects on the mixed forest regeneration dynamics was strongly influenced by the condition of sites. Therefore, management prescriptions should be adjusted in order to consider the environmental variation occurring through the entire landscape. An adaptive management that considers the pattern and process of sexual and asexual regeneration and disturbance will contribute to promote a greater resilience of mixed forest ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The management of forests faces a substantial challenge if the future capacity of these ecosystems to provide essential goods and services is to be maintained (Keenan 2015; Triviño et al. 2023). A thoughtful goal for silviculture is to promote resilient forests as coupled socio-ecological systems, able to maintain their essential functions and feedbacks even under physical and biotic drivers of change (Johnstone et al. 2016; Seidl et al. 2016; Charnley et al. 2017; Albrich et al. 2020). A silviculture more aligned with natural processes needs to have a comprehensive understanding of the pattern and process of stand development, including complex spatial scales and the role of disturbances in creating legacies that become key elements for the post-disturbance recovery (Johnstone et al. 2016; Ashton and Kelty 2018; Franklin et al. 2018; Kashian et al. 2023).

Regeneration from seeds and sprouts are natural process that decisively supports the continuity of the forest, and therefore it is crucial for forest resilience (Enright et al. 2014; Tredennick and Hanan 2015; Johnstone et al. 2016; Albrich et al. 2020). The composition, abundance and development of seeds and immature tree stages result from spatio-temporal changing processes that depend on the interplay between the ecological strategies of species and the biophysical and disturbance factors. These factors define the occurrence and functioning of microsites that provide essential conditions and resources for plant performance in the forest floor (Gholami et al. 2018; Kashian et al. 2023). Particularly, the composition and structure of adults strongly influence seed production and the viability, demography, spatial pattern and growth of seedlings and saplings (Puettmann et al. 2009; McDowell et al. 2020).

On a regional scale, ecosystems develop in a way that is extremely specific to site conditions (Weetman 1996). The microclimatic responses to forest structure, and its relative importance for driving biological processes, depend on their position in the landscape (Chen et al. 1999). In Nothofagus pumilio forests, factors that affect seedling growth within gaps were different in the site along the precipitation gradient analysed; while moisture limited seedling growth in xeric sites, light availability limited it in humid sites (Heineman et al. 2000, 2006). Regional climatic variation has also influenced the regeneration response to different silvicultural treatments (Torres et al. 2015; Rodriguez-Souvilla et al. 2023). Therefore, adoptions of short- and long-term management systems need knowledge about the response of regeneration to disturbances in the different environmental conditions (Smith et al. 1997; Chauchard 2012; Montes Pulido 2014; Keenan 2015; Ashton et al. 2018). Site condition is determinant of natural disturbance dynamics and provides reference conditions for sustainable management and biodiversity conservation (Berglund and Kuuluvainen 2021).

The subantarctic forest of northwestern Patagonia from Argentina is dominated by Nothofagus alpina, N. obliqua and N. dombeyi (Nothofagaceae). This mixed forest occurs in temperate and humid foothills of the Andes along a strong E-W increase of precipitation and on deep and drained volcanic soils (Lara et al. 1999). Most of the natural distribution of these mixed Nothofagus forests is located within Lanín National Park (Sabatier et al. 2011), where different protection levels exist. These Nothofagus species are dicline monoecious with masting, pollination and seed dispersal by wind, and a transient soil seed bank (Riveros et al. 1995; Dezzotti et al. 2016). Tree regeneration depends exclusively on sexual reproduction in the evergreen N. dombeyi, while vegetative reproduction is added in the deciduous N. obliqua and N. alpina, although seeds are important for colonization of new habitats in all species, asexual reproduction could be relevant for stand recovery after local disturbance (Veblen et al. 1996).

Natural and anthropogenic disturbances varying in frequency and severity affect Patagonian Nothofagus forests shaping their dynamics (Veblen et al. 1996). After a large-scale disturbance (e.g., fire, blowdown), pure and mixed Nothofagus forests typically pass through four recognizable stand development stages (sensu Oliver and Larson 1996): (1) stand initiation, (2) stem exclusion, (3) understory reinitiation, and (4) old growth. In general, the stand initiation stage of succession follows a “catastrophic regeneration mode” characterized by large patches of even-aged trees derived from a few survivors from within or surrounding areas (Oliver and Larson 1996). During the stem exclusion stage, self-thinning drastically reduces population density but increases the biomass of remaining trees (Loguercio et al. 2018). In the understory reinitiation stage, understory replenishment may start with seedlings in a “gap phase regeneration mode”, when gaps are opened up by the fall of mature individuals (Veblen et al. 1996). In the event that the stand is not affected by another large-scale disturbance, it will continue to the old-growth stage, in which canopy gaps are more frequent and produce environmental heterogeneity, promoting the establishment of regeneration and a forest with a mosaic of different ages (Veblen et al. 1996). Although Nothofagus are shade-intolerant, gap-dependent trees, they exhibit intraspecific divergences: N. dombeyi is the most light-demanding whereas N. alpina is the most shade-tolerant species (Weinberger and Ramírez 2001). The niche partitioning related to solar radiation manifests early during the life cycle and explains the variability in stand structure within this forest type (Dezzotti et al. 2003; Donoso et al. 2013; Sola et al. 2015, 2020; Marchelli et al. 2017; Dezzotti and Ponce 2018).

Silviculture of this forest type has traditionally been conducted within Lanín National Reserve (LNR) since the late 1980s by a shelterwood system. This system consists in a series of successive cuttings (e.g., preparatory, seeding, secondary, final) over a projected rotation of 140 years and a regeneration period of 20 years based on the characteristic of the species and defined in management plans of the LNR (González Peñalba and Lozano 2010; Chauchard 1988; Chauchard et al. 2012). Within this method the new cohort is protected against dehydration and freezing by the remnant trees (Ashton and Kelty 2018). In managed stands, the composition, abundance and growth of Nothofagus regeneration are related to micro-environmental changes in the forest floor that occur after different intensity and spatial pattern of tree cutting, basically given the differential performance of species to light intensity (Pollmann 2002; Dezzotti et al. 2003, 2004; Sola et al. 2015, 2020). However, seeding cutting regeneration is abundant only in those microsites with low levels of solar radiation and understory cover (Sola et al. 2016, 2020). Also, sprouting influences the composition and structure of forest (González Peñalba and Lozano 2009).

Although the effect of silviculture on regeneration at stand scales has been previously reported for different forest types, the consequences across landscapes and environmental gradients is less understood. The patterns and processes of regeneration at larger spatial scales could be even more critical for forests in which interactions are expected among dominant species exhibiting divergent ecological strategies (Johnstone et al. 2016; Kashian et al. 2023). The adaptive management based on the permanent evaluation of natural regeneration is a valuable approach to define silvicultural prescriptions particularly where treatments are expected to be strongly influenced by environmental and productive gradients (Bolte et al. 2009; Ashton and Kelty 2018; Franklin et al. 2018).

Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the influence of seeding cuttings over the dynamics of Nothofagus mixed forests across landscape (precipitation gradient). First, we aimed to analyse the dynamics of managed forest by evaluating the structure of sexual and asexual regeneration after < 10, 10–20 and > 20 years of tree harvest. We hypothesized that regeneration dynamics in managed forests respond differently to site conditions (precipitation intensity) and post-harvest period (< 10, 10–20, > 20 years); and we expected higher regeneration density in the humid than in the mesic site (due to greater water availability) and during the first period after management (due to greater light availability). Second, we aimed to evaluate the effect of silviculture on the structure of sexual regeneration by comparing primary and managed forests after more than 20 years of tree harvest. We hypothesized that regeneration dynamics change after management across the landscape and expected the higher regeneration density in managed forests of the humid site, due to greater resource availability.

Methods

Study area

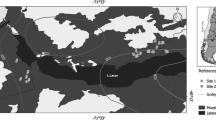

The study was located in the Nothofagus mixed forest of the Lácar-Nonthué lakes watershed (Parque Nacional Lanín, Neuquén province) (Fig. 1). The climate is temperate oceanic Cfb (Köppen-Geiger classification, Peel et al. 2007), with a pronounced longitudinal precipitation gradient and seasonality caused by the Andes rain shadow and the annual displacement of the pressure centre of the Pacific Ocean. In the far west, precipitation is abundant and distributed regularly throughout the year, while in the eastern part it is drastically reduced and concentrated during cold months (Garreaud et al. 2013). The mean values of temperature and total precipitation of Quechuquina weather station (40° 09′ S, 71° 34′ W, 730 m a.s.l., 1965–2013) is 9.3 °C and 1889 mm year−1, respectively (Dirección Provincial de Bosques de Neuquén, unpublished data). The vegetation corresponds to the Deciduous Forest District of the Subantarctic Ecoregion in which Nothofagus are the dominant tree species (Oyarzábal et al. 2018).

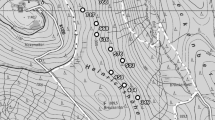

a Map of the Lácar–Nonthué lake watershed indicating the location of management plans of Chachín (humid site) and Quilanlahue-Yuco (mesic site). b, c Are the zoomed-in view of the humid and mesic sites. The circles represent the study plots and involve two different sampling designs, data analysis and results. Red and grey circles (18) are part of the system of permanent sampling plots (PSP) of the Lanín National Reserve. These PSP have measurements for more than 20 years and these data were used to analyse the dynamics of sexual and asexual regeneration after harvest. On the other hand, 4 of these plots for each site were selected (red circles) and 3 plots were installed in surrounding primary forests (blue circles). With the data from these 14 plots, the effect of silviculture on Nothofagus sexual regeneration was studied

Field methodology

The study area was occupied by mature forests of N. alpina, N. obliqua and N. dombeyi, part of which were harvested from 1988 to 2001 through seeding cuttings of the shelterwood system to achieve a canopy cover of around 40 per cent according to regulation and control of the Lanín National Reserve authorities (LNR). After that no other silvicultural treatment was applied, and the final cuttings have not been done yet. The ecological sustainability of silviculture was monitored approximately every five to seven years through a system of permanent sampling plots (PSP) by the LNR based on the study of tree composition, size and abundance as biological indicators.

Adult trees (diameter at breast height dbh > 10 cm) and asexual regeneration (sprouts of N. alpina and N. obliqua) were measured in 1000 m2-PSP, whereas sexual regeneration (dbh < 10 cm) were measured in subplots of 3–4 m2 located at the four main cardinal points of each PSP (González Peñalba and Lozano 2010). Sexual regeneration was divided according to total height (h) in h < 30, 30–200, > 200 cm, and this last class was categorized as established regeneration based on the relationship between individual survival potential and height (González Peñalba and Lozano 2010; Chauchard et al. 2012). The performance of asexual regeneration was inferred by counting the number of both sprouted stumps and sprouts per stump, and the height of the tallest sprout per stump (González Peñalba and Lozano 2010).

For this study, the sites of the PSP system Chachín (CHA, 40° 08′ 43″ S, 71° 39′ 40″ W) and Quilanlahue-Yuco (QUI, 40° 08′ 32″ S, 71° 28′ 58″ W) were selected for evaluation (Fig. 1). They exhibited north facing slopes and elevations varying from 700 to 1100 m a.s.l., and were categorized as humid (CHA, annual precipitation ≈ 2200 mm year−1) and mesic (QUI, ≈ 1800 mm year−1) by interpolation of meteorological data based on isohyets reported by Bianchi et al. (2016). In the managed forests, the dynamics of regeneration was analysed by categorizing measurements in three post-harvest periods (< 10, 10–20, and > 20 years) based on data from 18 PSP located at both site conditions. The assessment considered the composition and height class of the sexual regeneration and the composition, height and number of sprouts. For adult trees the analysis was based on the composition, density and basal area. The dbh frequency distribution was also analysed to evaluate the size structure of stands and particularly, to identify individuals of the smallest dbh class (10–20 cm) as former saplings incorporated into the adult cohort.

The effect of silviculture on sexual regeneration was evaluated for each site condition by comparing primary and managed forests after 20 years of tree harvest. The analysis was based on the composition, density, and height of sexual regeneration. Additionally, the composition, density, basal area, and size distribution of adult trees was evaluated. Four PSP located in managed forests were selected, and three additional PSP situated in surrounding primary forests were installed for comparison ((4 PSP + 3 PSP) × 2 sites = 14 PSP in total). Sexual regeneration was assessed in 12 subplots (SP) located at the four main cardinal points of each PSP (14 PSP × 12 SP = 84 SP in total).

Data analysis

The dynamics of sexual regeneration and adult trees was analysed by considering the factors of site condition (humid, mesic), post-harvest period (< 10, 10–20, > 20 years), and the interaction (site condition × post-harvest period) as fixed effect variables and the plot as a random variable nested in site. The analyses for sprouts considered the effects of the factors of species (N. alpina, N. obliqua), post-harvest period (< 10, 10–20, > 20 years), site condition (humid, mesic), stump diameter (< 40, 40–60, > 60 cm), and the interactions (species × post-harvest period, species × site condition). The effect of silviculture on sexual regeneration and adult trees was evaluated by considering the factors of site condition (humid, mesic), forest category (primary, managed forests > 20 years of tree harvest) and the interaction (site condition × forest category) as fixed effects, and the plot as random variable.

The sexual regeneration density, number of sprouts per stump and adult trees density were analysed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with the glmmTMB function (glmmTMB package) for discrete variables. Sprout height and basal area were evaluated with linear mixed-effect models (GLM) using the lme function (nlme package) for normal distributed data. The established regeneration over time was particularly analysed as a binary variable from incidence data (presence/absence) using a logistic regression (LR), since the response variable showed many null values (mainly for the first post-harvest periods). The asexual regeneration was also evaluated using LR considering sprouted and not sprouted stumps. The normality of the residual distribution of both the response and the random variables were verified using the Shapiro test (p < 0.05). Distributions for GLMMs were selected using Dharma and Akaike information criterion (tweedie and negative binomial distribution families), significance of the fixed effect variables using Anova function, and pairwise comparison using emmeans. The composition of sexual regeneration and adult trees was compared between sites for each post-harvest period in managed forest and, between forest category, using contingency tables, χ2 tests and Pearson residuals. Comparison of regeneration height between forest category and site condition was analysed using Kruskal–Wallis tests (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were based on R (vers. 3.2.5) and Statgraphics Centurion (vers. XVI.I) (p < 0.05).

Results

The dynamics of managed forests

Sexual regeneration

The analysis of total, N. alpina and N. dombeyi regeneration density showed a significant interaction between site condition and post-harvest period (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). The total density was 20 times higher in the humid site than in the mesic site during the 10–20 years period after harvest (Fig. 2a). In the last post-harvest period the regeneration density strongly decreased in the humid but not in the mesic site (Fig. 2a). Within the humid site, the difference for total regeneration density and for N. alpina and N. dombeyi density occurred between < 20 and > 20 years after harvest (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Table S1). At the mesic site there were no significant differences in regeneration density over time (Additional file 1: Table S1). The composition of sexual regeneration differed between site conditions in all post-harvest periods (χ2 = 2226.69, 8690.21, 2685.75 for the three post-harvest periods respectively, p < 0.05). Over time, the proportion of N. alpina regeneration was higher in the humid than in the mesic and N. obliqua proportion was higher in the mesic site than in the humid site. Nothofagus dombeyi was the dominant species in the regeneration density of both sites during the three post-harvest periods (64, 89 and 71%, for the humid site, and 73, 75 and 74% for the mesic site).

Density of sexual regeneration considering total regeneration (a) and established regeneration (b) of Nothofagus in the humid (left) and mesic site (right) in three post-harvest periods. The grey area of the left graph indicates the scale part used in the right graph. Density of adult trees (c) is also included, at the same sites and post-harvest periods, for comparisons with sexual regeneration

Site condition and post-harvest period showed significant effects on the presence of total, N. alpina and N. dombeyi established regeneration (Table 1), being lower for the first post-harvest periods and for the mesic site. In the humid site, the density of the established regeneration tended to show a maximum during the second post-harvest period and then began to decrease (Fig. 2b). In the mesic site, the established regeneration reached a lower density but continued to increase after 20 years of tree harvest (Fig. 2b). The height class frequency distribution of regeneration showed a similar pattern among species over time and therefore the species were plotted together (Fig. 3). A dominance of plants with h < 30 cm occurred in the first post-harvest period, and after that a larger proportion of plants with h > 30–200 cm occurred. In comparison to the mesic site, in the humid site the recruitment of plants with h < 30 increased after a longer period (Fig. 3).

Asexual regeneration

Species, site condition, post-harvest period and stump diameter showed a significant effect on the presence of sprouted stumps (Table 1). The sprouted stumps were higher for N. alpina, the mesic site, and the first post-harvest period. The smallest diameter class (< 40 cm) also had higher sprouted stumps (59%). Despite the interaction could not be analysed, a trend toward a greater decrease in N. obliqua sprouts in the humid site was observed over time (Fig. 4). The mean number of sprouted stumps for the first period was 80 ind ha−1. Species, site condition, post-harvest period and stump diameter exhibited a significant effect individually on any of the response variables (the number of sprouts per stump and the height of the sprouts), but not interactively (Table 1). Nothofagus alpina and the first post-harvest period showed a higher number of sprouts (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The sprouts showed larger heights in the mesic site, the intermediate diameter class (40–60 cm) and after 20 years of harvest, reaching a mean sprout height of 6.6 m.

Adult trees

Post-harvest period was the unique explanatory variable for both total and N. dombeyi density, and for total basal area (Table 1). As site condition was not significant, the forest structure is showed for both site conditions together (Fig. 5). The total density and the basal area increased over time, mainly for N. dombeyi (Figs. 2c, 5. The increase in N. dombeyi density occurred in the smallest diameter class after 20 years of harvest (Figs. 2c, 5). The adult trees of the smallest diameter class (10–20 cm) were mainly of N. dombeyi in the mesic site (69%) and of N. alpina in the humid site (64%). Nothofagus obliqua was the least abundant species in that diameter class. The composition of adult trees differed between site conditions in all post-harvest period (χ2 = 16.04, 15.60, 35.59 respectively, p < 0.05). Nothofagus alpina contributed over time more to the composition of the humid site and N. obliqua to the composition of the mesic site. Nothofagus dombeyi was the least abundant species within both sites in the three post-harvest periods (19, 14 and 24% for the humid site, 15, 13 and 32% for the mesic site).

The effect of silviculture

Sexual regeneration

The total and N. dombeyi regeneration density showed a significant interaction between site condition and forest category (Table 2). In the humid site there was no difference in the regeneration density by comparing managed and primary forest, whereas managed forest of the mesic site showed a higher density than primary forests (Fig. 6A, Additional file 1: Table S2). The composition of sexual regeneration differed between humid and mesic sites only in managed forests (χ2 = 1273.95, p < 0.05). Nothofagus alpina contributed more to the composition of the humid site and N. dombeyi to the composition of the mesic site. However, N. dombeyi was the most abundant in both sites (83 and 61% in the mesic and humid site, respectively). Similar composition was found in primary forests of both sites (χ2 = 1.39, p > 0.05). The mean regeneration height of managed forests (humid: \(\overline{x }\) = 3.23 m, se = 2.62, mesic: \(\overline{x }\) = 3.04 m, se = 2.10) differed from that of the primary forests (humid: \(\overline{x }\) = 0.34 m, se = 0.77; mesic: \(\overline{x }\) = 2.13 m, se = 2.09) (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05).

Density of Nothofagus regeneration in different site conditions and forest category (a) and established regeneration within managed and primary forests (b). Total: all three species. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of the mean and dissimilar lowercase letters significant differences among treatments within species (Tukey test, p < 0.05)

The forest category was the only factor that explained the variation of total density in the established regeneration (Table 2), being 13 times higher in managed than in primary forests (Fig. 6B, Additional file 1: Table S3). The forest category was also the unique factor that explained the variation of density in N. dombeyi established regeneration; this species also exhibited a higher density in managed forests in comparison to primary forests (Fig. 6b, Additional file 1: Table S3). In managed forests, the established regeneration represented 53% and 61% of the total regeneration density in the humid and mesic sites, respectively, whereas in primary forests the established regeneration represented 2% and 47% of the total density in the humid and mesic sites, respectively (Fig. 7).

Adult trees

Forest category explained the variation in total basal area in the primary (59 m2 ha−1) and managed forests (33 m2 ha−1) (Table 2). Site condition explained the variation in N. obliqua density in the mesic (77 ind ha−1) and humid site (27 ind ha−1) (Table 2). The diameter frequency distribution in the managed forests showed many individuals in the 10–20 diameter class mainly of N. dombeyi and N. alpina. Nothofagus alpina also exhibited a large number of individuals in the larger size classes (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). The primary forests showed a more flattened size distribution with less contribution of the smaller size classes (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). The composition of adult trees differed between the site conditions in the managed and primary forests, with a higher contribution of N. obliqua in the mesic site (χ2 = 26.49 and 27.07 for managed and primary forests respectively, p < 0.05).

Discussion

This long-term monitoring is a precursory study in analysing the dynamics of the Nothofagus forests from northwestern Patagonia, growing in a divergent precipitation regime and under a shelterwood system. Our results revealed that both silviculture and site condition are relevant factors modelling the dynamics of the regeneration of N. alpina, N. obliqua and N. dombeyi. The silviculture modifies the biotic and abiotic interacting factors that promote colonisation and establishment of immature individuals as light regime, soil properties, and understory cover, corroborating that site condition critically influences post-disturbance stand development (Martínez Pastur et al. 2014; Paredes et al. 2020; Li et al. 2022). Although Nothofagus regeneration was higher in the managed forest, site condition primarily defined by precipitation intensity affected the performance of this process. However, the difference in total regeneration density between humid and mesic sites during the first 20 years of harvest disappeared as time elapsed. The more positive water balance of the westernmost areas could have favoured a larger initial tree recruitment, although other ecological processes such as competition for light would have caused differential mortality over longer time scales. The decrease in the number of saplings during the last period would have been due not only to mortality but also to their incorporation into the adult cohort, caused by a diameter growth preliminarily estimated in 0.4 ± 0.2 cm year−1 (data not shown). However, this incorporation was relatively low (i.e., 42 and 29 ind ha−1 for the humid and mesic sites, respectively).

The opening of the canopy would have favoured not only seed germination and seedlings establishment but also the development of the advanced regeneration. The promotion of these young pre-harvest regeneration to the adult cohort could be particularly relevant for the most shade tolerant N. alpina (Dezzotti et al. 2003; Donoso et al. 2013; Sola et al. 2015). Although the present study did not determine the abundance of this category, trees that attained 10–20 cm dbh before 20 years of harvest would have already been present on the forest floor as pre-harvest regeneration, and those that reached this size after 20 years would have established later as post-harvest regeneration. Therefore, N. dombeyi would dominate the post-harvest regeneration in the mesic site (94% of total density) whereas N. alpina the pre-harvest regeneration in the humid site (73%).

The decrease in the density of N. obliqua adult trees over post-harvest time could be better explained by a lower incorporation of larger regeneration into the adult cohort than for a higher mortality. There was no interspecific difference in adult mortality after harvest, resulting in around 30% (8 ind ha−1) in more than 20 years (data not shown). A better understanding of the silvicultural effects on the pattern and process of stands under management requires to determine the contribution of the advance regeneration, because it constitutes a key biological legacy for post-disturbance recovery (Martínez Pastur et al. 2008; Johnstone et al. 2016; Ashton and Kelty 2018; Franklin et al. 2018; Kashian et al. 2023).

In comparison to the managed Nothofagus forests, the primary forests showed a larger basal area and a more balanced composition of regeneration. However, this regeneration showed lower mean heights due to the higher presence of one-year seedlings. In other temperate mixed forests, the larger seedling density of primary forests compared to managed counterpart was due to a higher seed production although subsequently few seedlings survived given greater shadow, litter depth, and competition with understory plants (Li et al. 2022). The decrease of canopy cover after tree harvest to 35–45% (Chauchard et al. 2012) was crucial for the process of regeneration in Nothofagus forests. However, N. dombeyi regeneration dominated the post-harvest microsites in both site conditions despite its lower contribution in the adult cohort. This compositional imbalance can be related to the capability of this species to colonize areas with extensive ranges of light and soil moisture (Veblen et al. 1996; Pollmann and Veblen 2004; Sola et al. 2020). In the Valdivian district of the subantarctic forest where Nothofagus species are stand-initiating pioneers, N. dombeyi dominates the initial phases of community development after the formation of small to medium-size gaps (Veblen et al. 1996; Müller-Using 2020). The larger proportion of N. alpina in the humid site and of N. obliqua in the mesic site can be linked to interspecific differences in adaptation to the seasonal climate and soil water content existing along the precipitation gradient (Weinberger and Ramírez 2001; Varela et al. 2012; Sola et al. 2020).

The comparatively limited abundance of sexual regeneration in the deciduous Nothofagus could partially be offset by sprouting, which was particularly abundant for N. alpina in the mesic site. During the first post-harvest period, the mean density of sprouted stumps for N. alpina and N. obliqua was 50 and 30 stems ha−1, respectively, of sprouts with 3.4 m height but much taller in stumps with 40–60 cm diameter. The sprout plays a key role in forest resilience because it contributes to incorporate part of the pre-harvest gene pool into the future forest, and therefore making more likely to maintain populations in place because of the higher capacity for recovery following disturbance and stress (Li et al. 2013, 2022; Aubin et al. 2016; Sola et al. 2016; Matula et al. 2020). However, the high mortality of sprouts due to self-thinning, particularly for N. obliqua in the humid site, suggests that the reduction of sprout number after harvest could be an adequate silvicultural prescription for developing taller and larger stems as previously proposed in other sprouting species (Li et al. 2013).

In summary, N. obliqua exhibited a comparative shortage of sprouts in the humid site, a low density of total and established regeneration in managed and primary forests, and a limited transitions from young to adult trees. These features could indicate that in the humid areas of the gradient, N. dombeyi and N. alpina would exhibit a greater competitive ability than N. obliqua at the initial stages of stand development. On the contrary, in the mesic areas, the low abundance of established regeneration for the primary and managed forests, and the limited transition of regeneration to adult trees recorded in N. alpina could indicate the restriction imposed on this species by the climate.

Management implications

The regeneration response to silvicultural treatments of mixed Nothofagus forests differed across spatial and temporal scales. Thus, relationships between microsite and forest structure developed at any single scale may not be applicable at other scales (Chen et al. 1999). The application of the same silvicultural management in sites with different environmental conditions has resulted in failures in regeneration, from a simple lack of regeneration to a shift in species composition (Weetman 1996; Dey et al. 2009; López-Bernal et al. 2012). The compositional dissimilarity found in this study, by comparing the post-harvest regeneration and adult cohort, was previously reported (Dezzotti et al 2003; Sola et al. 2020). Management systems of these Nothofagus forests should, therefore, diversify silvicultural practices throughout the forest landscape, to provide the micro-environmental conditions required by each species and to maintain biodiversity and forest functions.

In western plots of the watershed, the greater availability of water determined a higher recruitment after the reduction in canopy cover. However, saplings and sprouts should be thinned to avoid growth decreasing due to competition for light over time and to release less abundant species. This is possible because despite the greater abundance of N. dombeyi, N. alpina had also a considerable density of established regeneration in the humid site (1932 ind ha−1 after more than 20 years of harvest). In eastern plots of the watershed or with less availability of water, the lower tree recruitment, the grater compositional imbalance of the stands and the scarce established regeneration of N. alpina and N. obliqua suggest that different harvest intensities should be implemented between sites. Residual canopy cover greater than 50% should be tested to facilitate seedling establishment with more favourable conditions for mid-tolerant to shade species. A silviculture more aligned to natural processes should consider the creation of small and intermediate openings that would better imitate the natural falling of trees under small-scale perturbations. Establishment and survival of regeneration depend primarily on water and light availability, and therefore a particular combination of these regulators and resources in each site condition might favour one species or another (Peri et al. 2009; Martínez Pastur et al. 2011). Particularly, in sites with annual precipitation of around 1200 mm, N. alpina only establishes under conditions of canopy cover > 40% (Weinberger and Ramírez 2001). However, for N. obliqua and N. alpina and regardless site condition, silviculture should promote that saplings of > 200 cm height attain 2500 ind ha−1 as prescribed for the regeneration period (Chauchard et al. 2012), a condition that has not yet been completely achieved in all mixed Nothofagus forest.

Two considerations should be taken into account to compensate the scarce regeneration of both species. First, advance regeneration: careful logging should be applied to preserve pre-harvest regeneration, mainly of N. alpina, the highest commercial value species. This advance regeneration not only comes from many parent trees (greater effective population size) but also accelerates trees recolonization. Second, asexual reproduction: it would be of great importance to apply coppice management allowing sprouts of N. alpina and N.obliqua to reach the upper canopy. The strong shoot competition in each stump determines their progressive loss of vigor and, therefore, management should test the reduction of sprouts from stumps, anticipating competition and ensuring their adequate survival and growth.

All these prescriptions become even more relevant given the predictions of future climate scenarios to Nothofagus forests, in which an intense decrease in precipitation, greater frequency of disturbances (IPCC 2022) and a drastic reduction in the distribution range of N. alpina would be expected (Marchelli et al. 2017). Therefore, the adaptation of forests would be achieved by planning anticipatory silvicultural interventions that generate favorable microclimatic responses considering pattern and process of stand development and complex spatial scales. This adaptive forest management would allow mitigate the negative additive effects of both disturbances (harvest of trees + climate change) creating legacies that become key elements for the post-disturbance recovery.

Conclusions

Our study provides knowledge on regeneration dynamics of Nothofagus mixed forests, highlighting that silviculture should consider the environmental variation occurring through the entire landscape. The increase of tree regeneration after harvest indicates that the shelterwood system is ecologically suitable for the management of Nothofagus mixed forests. The ongoing monitoring will determine if the current low proportion of seedlings and saplings of N. alpina will increase after canopy closure. There are feasible silvicultural options that promote uneven-aged stands as occurred naturally, in which small-scale disturbances promote habitat heterogeneity and a shifting mosaic. The realization of this objective requires to consider explicitly the composition and abundance of the sexual and asexual regeneration existing before and after intervention, and the size variability of the artificial gaps. The transformation of the stand structure toward those exhibiting more spatial variability demands more frequent interventions along longer time scales. In order to promote the continuous supply of regeneration and harvestable trees, a particular attention should be paid to the vitality of individuals under different site conditions and level of canopy closure. An adaptive management that considers the pattern and process of regeneration and disturbance in the context of the physical variability of sites and microsites will contribute to promote a greater resilience of this Nothofagus forest ecosystem.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article including additional files are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Na :

-

Nothofagus alpina

- No :

-

Nothofagus obliqua

- Nd :

-

Nothofagus dombeyi

- PSP:

-

Permanent sampling plot

- LNR:

-

Lanín National Reserve

- dbh:

-

Diameter at breast height

- SP:

-

Subplot

- h :

-

Height

- CHA:

-

Chachín

- QUI:

-

Quilanlahue-Yuco

- GLMM:

-

Generalized linear mixed model

- GLM:

-

Linear mixed-effect model

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

References

Albrich K, Rammer W, Turner MG, Ratajczak Z, Braziunas KH, Hansen WD, Seidl R (2020) Simulating forest resilience: a review. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 29(12):2082–2096

Ashton MS, Kelty MJ (2018) The practice of silviculture: applied forest ecology. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Aubin I, Munson A, Cardou F, Burton P, Isabel N, Pedlar J, Pacquette A, Taylor AR, Delagrange H, Kebli C, Messier B, Shipley F, Valladares J, Kattge J, Boisvert-Marsh L, McKenney D (2016) Traits to stay, traits to move: a review of functional traits to assess sensitivity and adaptive capacity of temperate and boreal trees to climate change. Environ Rev 24(2):164–186. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2015-0072

Berglund H, Kuuluvainen T (2021) Representative boreal forest habitats in northern Europe, and a revised model for ecosystem management and biodiversity conservation. Ambio 50:1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01444-3

Bianchi E, Villalba R, Viale M, Couvreux F, Marticorena R (2016) New precipitation and temperature grids for northern Patagonia: advances in relation to global climate grids. J Meteorol Res 30:38–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13351-015-5058-y

Bolte A, Ammer C, Löf M, Madsen P, Nabuurs GJ, Schall P, Spathelf P, Rock J (2009) Adaptive forest management in central Europe: climate change impacts, strategies and integrative concept. Scand J For Res 24(6):473–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580903418224

Charnley S, Spies TA, Barros AMG, White EM, Olsen KA (2017) Diversity in forest management to reduce wildfire losses: implications for resilience. Ecol Soc 22(1):22. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08753-220122

Chauchard L (1988) Plan de manejo de un bosque de Rauli, Roble Pellin y Coihue, Parque Nacionl Lanin. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Parque Nacional Lanin. Inedito. Argentina

Chauchard L, Bava JO, Castañeda S, Laclau P, Loguercio GA, Pantaenius P, Rusch V (2012) Manual para las buenas prácticas forestales en bosques nativos de Nordpatagonia. Ministerio de Agricultura, ganadería y Pesca. Argentina

Chen J, Saunders SA, Crow TR, Naiman RJ, Brosofske KD, Mroz GD, Brookshire BL, Franklin JF (1999) Microclimate in Forest Ecosystem and Landscape Ecology: variations in local climate can be used to monitor and compare the effects of different management regimes. Bioscience 49(4):289–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313612

Dey D, Spetich M, Weigel D (2009) A suggested approach for design of oak (Quercus L.) regeneration research considering regional differences. New For 37:123–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-008-9113-8

Dezzotti A, Ponce O (2018) Early development of Nothofagus species from subantarctic forests under experimental conditions of light, substrate and ecological interaction. Cerne 24(2):149–161. https://doi.org/10.1590/01047760201824012507

Dezzotti A, Sbrancia R, Rodríguez-Arias M, Roat D, Parisi A (2003) Regeneración de un bosque mixto de Nothofagus (Nothofagaceae) después de una corta selectiva. Rev Chil Hist Nat 76(4):591–602. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-078X2003000400004

Dezzotti A, Sbrancia R, Roat D, Rodriguez-Arias M, Parisi A (2004) Colonización y crecimiento de renovales de Nothofagus después de cortas selectivas de un rodal en la Patagonia, Argentina. Investigación Agraria Sistemas y Recursos Forestales 13(2):329–338

Dezzotti A, Manzoni M, Sbrancia R (2016) Producción, almacenamiento en el suelo y viabilidad de las semillas de Nothofagus dombeyi, Nothofagus obliqua y Nothofagus alpina (Nothofagaceae) en un bosque templado del noroeste de la Patagonia argentina. Revista De La Facultad De Agronomía La Plata 115(2):155–172

Donoso PJ, Soto SD, Coopman RE, Rodriguez-Bertos S (2013) Early performance of planted Nothofagus dombeyi and Nothofagus alpina in response to light availability and gap size in a high-graded forest in the south-central Andes of Chile. Bosque 34(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002013000100004

Enright NJ, Fontaine JB, Lamont BB, Miller BP, Westcott VC (2014) Resistance and resilience to changing climate and fire regime depend on plant functional traits. J Ecol 102:1572–1581. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12306

Franklin JF, Johnson K, Johnson D (2018) Ecological forest management. Waveland Press, Long Grove

Garreaud R, López P, Minvielle M, Rojas M (2013) Large scale control on the Patagonia climate. J Climate 26(1):215–230. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00001.1

Gholami S, Saadat L, Sayad E (2018) Different microhabitats have contrasting effects on the spatial distribution of tree regeneration density and diversity. J Arid Environ 148:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.10.008

González Peñalba M, Lozano L (2009) Experiencias de Planificación Forestal en la Reserva Nacional Lanín. In: EcoGestión 2009: 1° Reunión sobre Planificación y Legislación Forestal de la Patagonia. Esquel

González Peñalba M, Lara A, Lozano L (2010) Plan de Manejo Forestal “Yuco Alto”, Reserva Nacional Lanín, Revisión Ordinaria. Administración de Parques Nacionales - Municipalidad de San Martín de los Andes, Inédito. Provincia de Neuquén.

Heinemann K, Kitzberger T (2006) Effects of position, understorey vegetation and coarse woody debris on tree regeneration in two environmentally contrasting forests of north-western Patagonia: a manipulative approach. J Biogeogr 33:1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01511.x

Heinemann K, Kitzberger T, Veblen T (2000) Influences of gap microheterogeneity on the regeneration of Nothofagus pumilio in a xeric old-growth forest of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. Can J For Res 30:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1139/x99-181

IPCC (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA

Johnstone JF, Allen CD, Franklin JF, Frelich LE, Harvey BJ, Higuera PE, Mack MC, Meentemeyer RK, Metz MR, Perry GLW, Schoennagel T, Turner MG (2016) Changing disturbance regimes, ecological memory, and forest resilience. Front Ecol Environ 14(7):369–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1311

Kashian D, Zak DR, Barnes B, Spurr SH (2023) Forest ecology. Wiley, New York

Keenan JR (2015) Climate change impacts and adaptation in forest management: a review. Ann For Sci 72:145–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-014-0446-5

Lara A, Rutherford P, Montory C, Bran D, Pérez A, Clayton S, Ayesa J, Barrios J, Gross M, Iglesias G (1999) Vegetación de la eco-región de los Bosques Valdivianos. Fundación Vida Silvestre Boletín Técnico 51:1–29

Li R, Zhang W, He J, Zhou J (2013) Survival and development of Liaodong oak stump sprouts in the Huanglong Mountains of China six years after three partial harvests. New For 44:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-011-9299-z

Li R, Yan Q, Xie J, Wang J, Zhang T, Zhu J (2022) Effects of logging on the trade-off between seed and sprout regeneration of dominant woody species in secondary forests of the Natural Forest Protection Project of China. Ecol Process 11:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-022-00363-3

Loguercio G, Donoso P, Muller-Using S, Dezzotti A (2018) Silviculture of temperate mixed forests from South America. In: Bravo-Oviedo A, Pretzsch H, Del Rio M (eds) Dynamics, silviculture and management of mixed forests. Springer, Cham, pp 271–317

Lopez-Bernal P, Defosse G, Quinteros P, Bava J (2012) Sapling growth and crown expansion in canopy gaps of Nothofagus pumilio (lenga) forests in Chubut, Patagonia, Argentina. For Syst 21:489–497

Marchelli P, Thomas E, Azpilicueta MM, Van Zonneveld M, Gallo L (2017) Integrating genetics and suitability modelling to bolster climate change adaptation planning in Patagonian Nothofagus forests. Tree Genet Genomes 13:119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1201-5

Martínez Pastur G, Lencinas M, Peri P, Cellini J (2008) Flowering and seeding patterns in unmanaged and managed Nothofagus pumilio south Patagonian forests. Forstarchiv 79:60–65

Martínez Pastur G, Peri PL, Cellini JM, Lencinas MV, Barrera M, Ivancich H (2011) Canopy structure analysis for estimating forest regeneration dynamics and growth in Nothofagus pumilio forests. Ann For Sci 68:587–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-011-0059-1

Martínez Pastur G, Soler RE, Cellini JM, Lencinas MV, Peri PL, Neyland Mark G (2014) Survival and growth of Nothofagus pumilio seedlings under several microenvironments after variable retention harvest in southern Patagonian forests. Ann For Sci 71(3):349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-013-0343-3

Matula R, Řepka R, Šebesta J, Pettit JL, Chamagne J, Šrámek M, Horgan K, Maděr P (2020) Resprouting trees drive understory vegetation dynamics following logging in a temperate forest. Sci Rep 10:9231. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65367-5

McDowell NG, Allen CD, Anderson-Teixeira K, Aukema BH, Bond-Lamberty B, Chini L, Clark JS, Dietze M, Grossiord C, Hanbury-Brown A, Hurtt GC, Jackson RB, Johnson DJ, Kueppers L, Lichstein JW, Ogle K, Poulter B, Pugh TAM, Seidl R, Turner MG, Uriarte M, Walker AP, Xu C (2020) Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science 368(6494):eaaz9463. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz9463

Montes Pulido CR (2014) La silvicultura como elemento crítico para la sostenibilidad y el manejo del bosque. Rev Inv Agr y Amb 5(1):147. https://doi.org/10.22490/21456453.942

Müller-Using S (ed) (2020E) El Manejo de Renovales de Roble-Raulí-Coihue en una Resumida Mirada: Estadísticas e investigaciones en curso. Instituto Forestal, Chile

Oliver CD, Larson BC (1996) Forest stand dynamics. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Oyarzabal M, Clavijo J, Oakley L, Biganzoli F, Tognetti P, Barberis I, Maturo HM, Aragón R, Campanello PI, Prado D, Oesterheld M, León RJ (2018) Unidades de vegetación de la Argentina. Ecol Austral 28(1):40–63. https://doi.org/10.25260/EA.18.28.1.0.399

Paredes D, Cellini JM, Lencinas MV, Parodi M, Quiroz D, Ojeda J, Farina S, Rosas YM, Martínez Pastur G (2020) Influencia del paisaje en las cortas de protección en bosques de Nothofagus pumilio en Tierra del Fuego, Argentina: Cambios en la estructura forestal y respuesta de la regeneración. Bosque 41(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002020000100055

Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA (2007) Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 11:1633–1644. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007

Peri PL, Martínez Pastur G, Lencinas MV (2009) Photosynthetic response to different light intensities and water status of two main Nothofagus species of southern Patagonian forest, Argentina. J For Sci 55(3):101–111

Pollmann W (2002) Effects of natural disturbance and selective logging on Nothofagus forests in south-central Chile. J Biogeogr 29(7):955–970

Pollmann W, Veblen TT (2004) Nothofagus regeneration dynamics in south-central Chile: a test of a general model. Ecol Monogr 74(4):615–634

Puettmann KJ, Coates KD, Messier C (2009) A critique of silviculture: managing for complexity. Island Press, Washington DC

Riveros M, Palma B, Erazo S, O’Reilly S (1995) Phenology and pollen flow in species of the genus Nothofagus. Phyton 57:45–54

Rodríguez-Souilla J, Cellini JM, Lencinas MV, Roig FA, Chaves JE, Aravena Acuna M, Peri PL, Martínez Pastur GJ (2023) Variable retention harvesting and climate variations influence over natural regeneration dynamics in Nothofagus pumilio forests of Southern Patagonia. Forest Ecol Manag 544:121221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121221

Sabatier Y, Azpilicueta M, Marchelli P et al (2011) Distribución Natural de Nothofagus alpina y Nothofagus obliqua en Argentina, dos especies de importancia forestal de los bosques templados patagónicos. Bol Coc Argent Bot 46(1–2):131–138

Seidl R, Spies TA, Peterson DL, Stephens SL, Hicke JA (2016) Searching for resilience: addressing the impacts of changing disturbance regimes on forest ecosystem services. J Appl Ecol 53(1):120–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12511

Smith D, Larson B, Kelty M, Ashton P (1997) The practice of silviculture: applied forest ecology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, USA, p 537

Sola G, Attis Beltrán H, Chauchard L, Gallo L (2015) Effect of silvicultural management on the Nothofagus dombeyi, N. alpina and N. obliqua forest regeneration within the Lanín National Reserve (Argentina). Bosque 36:113–120. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002015000100012

Sola G, El Mujtar V, Tsuda Y, Vendramin G, Gallo L (2016) The effect of silvicultural management on the genetic diversity of a mixed Nothofagus forest in Lanín National Reserve, Argentina. Forest Ecol Manag 363(1):11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.12.018

Sola G, El Mujtar V, AttisBeltrán H, Chauchard L, Gallo L (2020) Mixed Nothofagus forest management: a crucial link between regeneration, site and microsite conditions. New For 51(3):435–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-019-09741-w

Torres AD, Cellini JM, Lencinas MV, Barrera MD, Soler RM, Díaz-Delgado R, Martínez Pastur G (2015) Seed production and recruitment in primary and harvested Nothofagus pumilio forests: influence of regional climate and years after cuttings. For Syst 24:e016. https://doi.org/10.5424/fs/2015241-06403

Tredennick A, Hanan NP (2015) Effects of tree harvest on the stable-state dynamics of savanna and forest. Am Nat 185(5):E153–E165. https://doi.org/10.1086/68047

Triviño M, Potterf M, Tijerín J, Ruiz-Benito P, Burgas D, Eyvindson K, Blattert C, Mönkkönen M, Duflot R (2023) Enhancing resilience of boreal forests through management under global change: a review. Curr Landsc Ecol Rep 8:103–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40823-023-00088-9

Varela S, Fernández M, Gyenge J, Aparicio A, Bruzzone O, Schlichter T (2012) Physiological and morphological short-term responses to light and temperature in two Nothofagus species of Patagonia, South America. Photosynthetica 50(4):557–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-012-0064-0

Veblen TT, Donoso C, Kitzberger T, Rebertus A (1996) Ecology of southern Chilean and Argentinean Nothofagus forests. In: Veblen TT, Hill R, Read J (eds) The ecology and biogeography of Nothofagus forests. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 293–353

Weetman G (1996) Are European silvicultural systems and precedents useful for British Columbia silviculture prescriptions? Canadian Forest Service and B.C. Ministry of Forests, Victoria, B.C. FRDA Report No. 239

Weinberger P, Ramírez C (2001) Microclima y regeneración natural de raulí, roble y coigüe (Nothofagus alpina, N. obliqua y N. dombeyi). Bosque 22(1):11–26. https://doi.org/10.4206/bosque.2001.v22n1-02

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Natalia Fernandez and Franco Floriani for their contribution in plots establishment and regeneration sampling, Fabio Trinco for his contribution in characterization of precipitation gradient and Fernando Umaña to kindly provide the map of the studied plots.

Funding

This study was funded by CONICET, FONCYT [PICT-2020-SERIEA-00931 “Indicadores de manejo forestal sustentable: regeneración arbórea y diversidad biológica en el bosque mixto de Nothofagus alpina, N. obliqua y N. dombeyi en diferentes condiciones ambientales de sitio y micrositio”] and the Universidad Nacional del Comahue [PI 04/S025 “Resiliencia, disturbios y servicios ecosistémicos del Bosque Subantártico”].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GS, CM, AD, PM, and VEM conceived the experimental strategy. GS, CM, AD, PM, HAB, RS, MGP and VEM selected the sampling areas in managed and primary forests. MGP and ML gave us access to information of the permanent sampling plots. GS, CM, HAB, RS, MGP and ML collected field data. GS, CM, HAB, PM and VEM contributed with data analysis. GS, CM, AD and VE were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

The scope of the results is supported by the coordination between the authors of the participating institutions (INTA, CONICET, APN-PNL, UNCo), whose history of joint work dates back more than 20 years. This articulation represents not only a strength of the research, but a distinctive characteristic, giving continuity to previous works with a strong component of integration between knowledge generation and its application.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional files : Table S1.

Significance for the analyses of the regeneration density within the managed forests. Figure S1. Number of sprouts per stump of N. alpina and N. obliqua in three post-harvest periods. Table S2. Regeneration density of Nohofagus in different site conditions and forest category. Table S3. Density of established regeneration of Nothofagus in different forest categories. Figure S2. Diameter frequency distribution of Nothofagus adult trees in managed forests after 20 yr of harvest (above), and in primary forests (bellow) for the humid (left) and mesic site (right).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sola, G., Mateo, C., Dezzotti, A. et al. Long-term monitoring reveals the effect of precipitation and silviculture on Nothofagus regeneration in Northern Patagonia mixed forests. Ecol Process 13, 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-024-00509-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-024-00509-5