Abstract

Background

Baseline levels of tree mortality can, over time, contribute to high snag densities and high levels of deadwood (down woody debris) if fire is infrequent and decomposition is slow. Deadwood can be important for tree recruitment, and it plays a major role in terrestrial carbon cycling, but deadwood is rarely examined in a spatially explicit context.

Methods

Between 2011 and 2019, we annually tracked all trees and snags ≥1 cm in diameter and mapped all pieces of deadwood ≥10 cm diameter and ≥1 m in length in 25.6 ha of Tsuga heterophylla / Pseudotsuga menziesii forest. We analyzed the amount, biomass, and spatial distribution of deadwood, and we assessed how various causes of mortality that contributed uniquely to deadwood creation.

Results

Compared to aboveground woody live biomass of 481 Mg ha−1 (from trees ≥10 cm diameter), snag biomass was 74 Mg ha−1 and deadwood biomass was 109 Mg ha−1 (from boles ≥10 cm diameter). Biomass from large-diameter trees (≥60 cm) accounted for 85%, 88%, and 58%, of trees, snags, and deadwood, respectively. Total aboveground woody live and dead biomass was 668 Mg ha−1. The annual production of downed wood (≥10 cm diameter) from tree boles averaged 4 Mg ha−1 yr−1. Woody debris was spatially heterogeneous, varying more than two orders of magnitude from 4 to 587 Mg ha−1 at the scale of 20 m × 20 m quadrats. Almost all causes of deadwood creation varied in importance between large-diameter trees and small-diameter trees. Biomass of standing stems and deadwood had weak inverse distributions, reflecting the long period of time required for trees to reach large diameters following antecedent tree mortalities and the centennial scale time required for deadwood decomposition.

Conclusion

Old-growth forests contain large stores of biomass in living trees, as well as in snag and deadwood biomass pools that are stable long after tree death. Ignoring biomass (or carbon) in deadwood pools can lead to substantial underestimations of sequestration and stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-diameter trees and logs (diameter ≥60 cm diameter at breast height; DBH) are a defining feature of old-growth forests (Lutz et al. 2018), and they contribute disproportionately to ecosystem function (Lutz et al. 2012, 2013, 2014; Thorn et al. 2020). It is axiomatic that downed wood (hereafter; deadwood) of large diameters must originate from snags or trees of equal or greater diameter—to wit, there can be no large logs without there having been large trees first (Spies et al. 1988). These large logs contribute directly to biodiversity by changing the microenvironment (Chen et al. 1995; Vrška et al. 2015; Chu et al. 2019), serving as substrate for seedlings (Harmon and Franklin 1989) and bryophytes (Taborska et al. 2015), and contributing to complex and prolonged patterns of carbon cycling (Harmon et al. 1986; Privetivy et al. 2018; Stenzel et al. 2019). In addition to the large pieces of deadwood that come from the main stem of large-diameter trees, large trees contribute smaller pieces of wood as well. Chronic wind disturbance in Pacific Northwest forests is a defining ecological process (Lutz and Halpern 2006; Larson and Franklin 2010), and the tops of older, taller trees are frequently broken. Wood that originates from the tops of larger trees may persist longer on the forest floor compared to a full tree of the same diameter by virtue of being generally older and having tighter rings and more heartwood. When large-diameter trees fall, their tops also sometimes shatter into smaller diameter pieces. The causes of mortality also differ between small- and large-diameter trees (Larson et al. 2015; Das et al. 2016), potentially leading to different snag fall rates and decomposition trajectories (Harmon et al. 1986). The windthrow from the tops of large-diameter trees and subsequent epicormic growth contributes to the vertical heterogeneity of Pacific Northwest forests (Kane et al. 2010; Kane et al. 2011; Sillett et al. 2018), and those logs continue to drive horizontal heterogeneity through crushing smaller stems, opening canopy gaps, and providing substrate for regeneration (Chen et al. 2004; North et al. 2004; Larson and Franklin 2010; Lutz et al. 2014).

Deadwood is abundant in Pacific Northwest forests that have been without fire and timber harvest long enough for trees to grow, die, and fall (Spies et al. 1988; Harmon et al. 2004; Larson et al. 2008; Freund et al. 2014). This deadwood not only fulfills important ecological roles within these forests (Franklin et al. 1981), but it also comprises a considerable amount of forest carbon (Smithwick et al. 2002). Although this carbon is often classified as transitory because deadwood eventually decays, the size distribution and species composition of deadwood regulate the rate of carbon flux from live biomass into soil, microbial, and atmospheric carbon pools (Harmon et al. 2013). Decay of deadwood in wet, temperate forests, can be extremely slow, with large logs persisting for centuries (Harmon et al. 2020). It is often assumed that carbon is quickly released following the death of a tree (e.g., Berner et al. 2017), but the long residence time of large deadwood renders their carbon effectively sequestered for many decades or centuries (e.g., Erb et al. 2016; Körner 2017; Stenzel et al. 2019). As the largest 1% of living trees can comprise roughly 50% of aboveground biomass (Lutz et al. 2018), we expect that large deadwood may also represent a considerable proportion of dead, but relatively stable, forest carbon. Accurately quantifying the size and spatial structure of deadwood will improve our understanding of forest carbon dynamics, providing a stronger empirical basis for models of global carbon stocks (Pan et al. 2011) and turnover (Carvalhais et al. 2014). We wanted to examine what losses there might be to carbon pools if there were no large-diameter trees. Specifically, if trees were limited to smaller diameters, how much of the woody carbon pools would be absent?

In this study, we tracked the amount, spatial distribution, and fluxes of biomass from trees to deadwood, and we examined the unique contribution of large-diameter trees to the deadwood pool and to the biomass dynamics of an old-growth forest. Using a spatially explicit data set of trees, snags, and down woody debris, our aim was to determine:

-

1)

The abundances, relative proportions, and spatial patterns of aboveground woody biomass in live tree, snag, and deadwood pools.

-

2)

The proportion of biomass accounted for by large-diameter trees.

-

3)

How different causes of mortality influence the creation of deadwood pools.

Materials and methods

Description of study site

The Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot (WFDP; Lutz et al. 2013) is a 27.2 ha (of which, 25.6 ha analyzed here) plot located at a mean elevation of 362 m in Tsuga–Pseudotsuga forest in southwestern Washington (Fig. 1). The WFDP experienced a stand-initiating fire circa 525 years ago and has since developed a complex structure characterized by both horizontal and vertical diversification (Franklin et al. 2002; Parker et al. 2004). The dominant species by biomass is Tsuga heterophylla, the shade-tolerant late seral species in this ecosystem, followed by Pseudotsuga menziesii, the early seral, long-lived pioneer species. The abundance of stems is driven by the subcanopy tree (or tall shrub) Acer circinatum and Tsuga heterophylla (see Lutz et al. 2013 for complete abundances). Despite the relative dominance of these species and the low woody species richness (26 species ≥1 cm DBH), the WFDP is phylogenetically diverse because of the presence of both basal gymnosperms and a variety of Rosaceae and Ericaceae (Erickson et al. 2014; Wills et al. 2021). Botanical nomenclature follows Flora of North America (1993+).

The Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot (WFDP) is located in the Tsuga–Pseudotsuga vegetation zone in the Pacific Northwest of North America (a) on the western slopes of the Cascade Range (b). The WFDP has relatively gentle topography (32 m of vertical relief within 25.6 ha), and the plot features a surveyed 20-m grid (c). a Digital elevation model shading from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (2000). c Topographic lines are a 1-m digital elevation model derived from LiDAR (2012). Background in b is a composite of Landsat 8 scenes

Data collection

Within the WFDP, every woody stem ≥1 cm DBH has been identified, measured, mapped, and tagged according to the protocols of the Smithsonian Forest Global Earth Observatory network (ForestGEO; Anderson-Teixeira et al. 2015; Lutz 2015; Davies et al. 2021). In addition, all down woody debris originating from the main stems of trees ≥10 cm diameter was mapped according to the Smithsonian ForestGEO deadwood protocol (Janík et al. 2018), including the rooting location of the originating tree for those trees that fell prior to the plot establishment (when it could be determined; otherwise, it was assumed to be at the larger end of the log). Since the origination of the plot in 2010–2011, new deadwood production from trees and snags was tracked annually (2012 to 2019). From 2017, we also identified top pieces from trees and snags ≥10 cm DBH that had broken and mapped them, either recording or estimating the year each top broke (the precise year could not always be ascertained but was between 2012 and 2019).

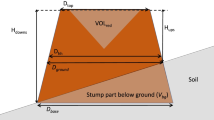

Volume and biomass calculations

The biomass of live trees was calculated using biomass equations selected from Chojnacky et al. (2014) and other sources (Lutz et al. 2017a; Means et al. 1994; Van Pelt et al. 2016; see Table S1 for listing of equations). All abundant species were covered by the equations of Chojnacky et al. (2014), but we used more specific equations for some shrub taxa to match site morphology. The Chojnacky et al. (2014) equations that we used have a minimum applicable diameter of 3 cm DBH, leading to very low (or even negative) biomass estimates for trees 1 cm ≤ DBH < 3 cm. We accordingly set minimum biomass values for small-diameter stems of the most common genera as follows: Vaccinium, Menziesia, Gaultheria, Lonicera, Rhamnus, and Rosa—100 g; Acer—250 g; and Abies, Tsuga, Pseudotsuga, Pinus, Taxus, and Thuja—300 g (Table S1, Fig. S1).

For snags that died soon after plot establishment (decay class 1 or 2) and were still intact (first-order branches present, bark intact, and top diameter ≤10 cm), biomass was estimated with species-specific allometric equations (Table S1) and corrected with the species- and decay-class-specific relative density factors of Harmon et al. (2008). For snags that were either in a more advanced state of decay or were not intact, their biomass was estimated by modeling their volume as a conic frustum and using the species and decay-class-specific absolute density values provided by Harmon et al. (2008).

For individual pieces of wood on the ground, we calculated volume from their physical dimensions, assuming their shape was a conic frustum. Biomass was calculated for the entire originating tree using species-specific allometric equations (Table S1) and attributed to specific pieces that fell from that tree by weighting a piece according to its volume as a proportion of the total volume of the tree, including any remaining standing volume. Biomass was then corrected for decay class using the relative density factors of Harmon et al. (2008). For detailed definitions of decay classes, see Janík et al. (2018) as implemented by Lutz et al. (2020, 2021). For pieces that could not be identified to species, we used an average value for the genus calculated by proportionally weighting the identified pieces from the data set and their characteristics. For pieces that could only be identified to the family or not at all, we used a proportional average for all the members of that family in our site or of all wood, respectively (0.386 g cm−3 for decay class 1; 0.324 g cm−3 for decay class 2; 0.213 g cm−3 for decay class 3; 0.146 g cm−3 for decay class 4; and 0.128 g cm−3 for decay class 5). We calculated mean values of total tree, snag, and deadwood biomass for the entire plot and variability at the spatial grain of 20 m × 20 m. We also calculated the directionality of deadwood pieces using a null model of uniform distribution.

Partitioning of biomass and causes of mortality

In addition to our primary partitioning of biomass into live trees, snags, and deadwood, we differentiated woody structures depending on whether they originated from trees that were large considering both regional (≥90 cm DBH) and global (≥60 cm DBH) contexts. We calculated the large-diameter threshold (that tree diameter that divides biomass into two equal portions sensu Lutz et al. 2018). We also assessed biomass fluxes as a function of the primary cause of mortality for each tree (including unknown cause, for live trees) following the methods of the Western Forest Initiative (Furniss et al. 2020). Pathology exams were conducted for each newly dead tree in the year of death. Pathogenic fungi were distinguished from saprophytic fungi, where pathogens attacked live portions of the tree (cambium and phloem, e.g., Armillaria ostoyae) and saprophytes attacked primarily dead portions of the tree (sapwood and heartwood, e.g., Phellinus weirii). Trees exhibiting mechanical failure due to saprophytic fungi or animals (e.g., elk trampling) were considered to have been killed by these underlying agents rather than the mechanical failure itself. Windthrow was defined as trees falling or breaking as a result of wind, snow, or fluvial activity. Crushing was defined as trees fallen, buried, or broken by other falling trees or debris. Insects were primarily bark beetles (family Scolytidae, genera Dendroctonus and Scolytus). Animal activity was primarily herbivory and scraping damage by elk (Cervus canadensis), which are locally abundant. Mistletoe was primarily Arceuthobium campylopodum subsp. tsugense, which affects Tsuga heterophylla. Suppression was determined when trees exhibited irregular growth indicative of strong light competition (e.g., flat crowns).

We conducted an analysis of variance using linear models with post hoc Tukey tests to compare biomass accumulation among mortality factors between large-diameter (DBH ≥60 cm) and smaller (1 cm ≤ DBH < 60 cm) trees. For this, the response variable was total wood biomass produced by each tree (kg), and the predictor was multinomially categorized tree mortality agent (including “none” for live trees). Significance was assessed at the family-wise controlled error rate of α = 0.05. To verify these results, we also ran variable importance tests using Random Forests with the same model formulation. For both tests, all trees alive at plot establishment were analyzed (n = 33,739; mortality n = 4,548).

All calculations were performed in R version 3.6.2 (R Core Team 2020) using packages randomForest (Liaw and Wiener 2002), rgdal version 1.4-8 (Bivand et al. 2019), rgeos version 0.5-2 (Bivand and Rundel 2019), sp version 1.3-2 (Pebesma and Bivand 2005), and sf version 0.8-1 (Pebesma 2018).

Results

Aboveground live biomass from trees ≥10 cm diameter in 2019 was 481 Mg ha−1. Snag biomass was 74 Mg ha−1 and deadwood biomass from stems ≥10 cm diameter of 109 Mg ha−1. There was a total of 6104 portions of main stems ≥10 cm diameter in 25.6 ha (Fig. 2, Table 1). The large-diameter threshold (i.e., the DBH above which trees comprise 50% of aboveground live biomass) for the WFDP was 91.7 cm. Trees ≥60 cm DBH accounted for 85%, 88%, and 58% of tree, snag, and deadwood biomass, respectively. Trees ≥90 cm diameter accounted for 53% of tree biomass, 55% of snag biomass, and 27% of deadwood biomass (Fig. S13). The largest 1% of downed trees accounted for 17% of deadwood biomass. When considered by count, smaller-diameter trees contributed the majority of deadwood (91% of trees and 85% of pieces; Table 1). However, when considered by metrics of volume or biomass, large-diameter trees dominated, representing 56% of volume and 58% of total biomass (Table 1).

Deadwood biomass varied by over two orders of magnitude (Fig. 3; 4 Mg ha−1 to 587 Mg ha−1, mean 109 Mg ha−1). This variation was sustained across various metrics of deadwood abundance (Fig. 3). Annual variation in deadwood accumulation was high (Figs. S2–S12), but no trend could be detected with this first decade of data. Spatial heterogeneity of all biomass pools was high at the scale of 20 m × 20 m quadrats, but the majority of 20 m × 20 m quadrats had biomass dominated by large pieces of wood (Fig. 4, Figs. S13, S14).

Spatial heterogeneity in the biomass of large woody debris on the ground in the Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot in 2019. The number of trees that fell (a) is 70% of pieces on the ground (b) showing that most trees fell intact, although some shattered. Maximum local volume of deadwood was over seven times the mean (c), and the maximum total biomass was over five times the mean (e). The maximum local biomass contributed by large-diameter trees was nine times the mean (d). Each dot represents one of the 640, 20 m × 20 m quadrats in 25.6 ha of the Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot

Large-diameter trees and all trees ≥10 cm diameter showed weak eastern directionality, suggesting that prevailing storm tracks may have partially determined the final orientation of pieces of wood (Fig. 5). For all trees ≥10 cm DBH, directionality was easterly and southerly (χ2 test, P < 0.001); 30% fell in an easterly direction, 19% in a westerly direction, 25% northerly, and 26% southerly. For the trees ≥60 cm DBH (1225 trees), directionality was also easterly and southerly (χ2 test, P < 0.001); 31% easterly, 17% westerly, 22% northerly, and 29% southerly. The mean diameter of old deadwood (i.e., pre-establishment) accumulation was 40 cm (Fig. 6). Deposition of large-diameter deadwood was less frequent, but long-term persistence of these pieces meant that their proportion of total deadwood biomass was relatively high (Figs. 4 and 6, dotted line).

Directional diagrams of the position of deadwood ≥10 cm diameter (a) and of deadwood ≥60 cm diameter (b) in the Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot in 2019. Each concentric gridline of the rose diagram represents 2% of the total pieces. The directions of treefall were different than would be expected from a uniform distribution

Diameter distribution of deadwood ≥10 cm diameter from 2012 to 2019 in the Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot, as well as the diameter distribution of deadwood that existed at plot establishment in 2011. Colors correspond to those in Fig. 2. Curves are based on the raw diameters smoothed with a Gaussian density kernel. The square-root transformation of the y-axis shows the low frequency but cumulative effects of large-diameter inputs

The mean diameter of old deadwood (i.e., pre-establishment) accumulation was 40 cm (Fig. 6). Deposition of large-diameter deadwood was less frequent, but long-term persistence of these pieces meant that their proportion of total deadwood biomass was relatively high (Fig. 6, dotted line).

The annual production of downed wood (≥10 cm diameter) from tree boles averaged 4 Mg ha−1 yr−1. By 2019, 3% of the tree biomass that was alive at establishment had become deadwood. Of wood that fell from trees that were alive at establishment, the majority of deadwood biomass (80%) was produced by trees or snags ≥ 60 cm DBH, primarily Pseudotsuga menziesii and Tsuga heterophylla. Random Forests and Tukey tests agreed that saprophytic fungi (often leading to mechanical failure) and non-rot associated windthrow contributed the most to accumulation of deadwood (7.2 Mg ha−1 and 3.4 Mg ha−1, respectively). The third largest contributors to deadwood accumulation were pieces that fell from still-living trees (3.1 Mg ha−1). Of the deadwood biomass that fell from live trees, 87% came from trees ≥60 cm DBH. Together, these three categories produced 88.8% of deadwood originating from trees that were alive at plot establishment. Causes of mortality and snagfall were different between large-diameter and smaller-diameter trees (Fig. 7). Mortality causes had significantly different effects on deadwood creation depending on tree diameter. When compared with small-diameter trees, large-diameter trees as a group produced 57.8 Mg more when alive, 4.4 Mg less from crushing, 40.8 Mg more from windthrow, 6.1 Mg less from pathogens, 144.3 Mg more from saprophytes, 2.4 Mg more from insects, 1.7 Mg more from mistletoe, and 0.3 Mg less from suppression (there was no deadwood produced by suppressed large trees in the study period). Tukey tests showed that most causes of mortality were significantly distinct in the biomass of snags and deadwood created. After controlling the family-wise error rate at α=0.05, there were no significant differences in the biomass contribution of causes classified as “animal” or “other” to mortality. Differences in wood fluxes from living tree to deadwood were also apparent (Fig. 7). Large-diameter trees constituted 11,142.2 Mg in 2011. Those trees were responsible for 316.2 Mg of deadwood, with 68.2 Mg of that transitioning directly from the live biomass pool to deadwood (Fig. 7, top line). In contrast, small-diameter trees represented 2108.9 Mg in 2011, with 79.6 Mg joining the deadwood pool by 2019, and 10.4 Mg transitioning directly from the live biomass pool to deadwood (Fig. 7, bottom line).

Snag and deadwood biomass produced by mortality agents as a proportion of all wood originating from trees alive at plot establishment that would eventually fall or die delineated by large-diameter trees (≥60 cm DBH) and small-diameter trees (1 cm ≤ DBH < 60 cm). Of the 13,251 Mg of total tree biomass present in 2011 in 25.6 ha, 851 Mg died, 396 Mg fell to the ground, and 12,400 Mg remained alive by 2019. The horizontal brown bars at the top and bottom of the figure represent the tops of trees that broke off and fell to the ground leaving the (somewhat shortened) tree alive. The height of each bar represents the proportion of biomass that transitioned from trees directly to deadwood, or from trees to snags and then to deadwood, grouped by primary mortality agent

Discussion

Large-diameter structures, whether trees, snags, or deadwood, accounted for a large majority of biomass. In this Tsuga–Pseudotsuga forest, fully 81% of live and dead aboveground woody biomass is contained in individuals ≥60 cm DBH or in pieces of deadwood originating from those large-diameter trees. Naturally, large-diameter trees are prerequisite to the presence of large-diameter snags and deadwood. Despite the importance of small-diameter trees to species biodiversity (i.e., Memiaghe et al. 2016; Das et al. 2018; Ellison et al. 2019) and demographic rates (Table S2, Lutz and Halpern 2006; Halpern and Lutz 2013), these smaller stems do not contribute much to woody biomass flux or deadwood pools (Table 1). Hence, the prevalence of large-diameter trees—with their substantial and enduring contribution to both live and dead biomass—reinforces the ecological significance of large-diameter trees even beyond their death (Fig. 4; Erb et al. 2016; Lutz et al. 2018).

The amount of deadwood produced depended significantly upon mortality agent (Fig. 7; Larson and Franklin 2010; Larson et al. 2015). Notably, the distribution of deadwood fluxes among large-diameter trees and small-diameter trees differed (Fig. 7). The majority of biomass was killed by saprophytes, pathogens, and windthrow. Biomass transitioned quickly to deadwood when saprophytes or windthrow were the cause of mortality, while the remaining biomass killed by other mortality agents largely remained in the snag pool. Though bark beetles attack large-diameter trees, for example, this carbon is primarily transferred to snag biomass rather than deadwood. Similar patterns of agent-related deadwood accumulation have been described in dry temperate forests following fire (Lutz et al. 2020), highlighting that saprophytic fungal activity can dominate carbon fluxes across a range of temperate forest types. Changes to the relative frequency of different mortality processes will therefore have reverberating effects on subsequent deadwood accumulation and carbon storage across temperate forests. Specifically, the growing preponderance of unprecedented bark beetle epidemics (e.g., Weed et al. 2013) is likely to favor much slower rates of large deadwood accumulation (Hicke et al. 2012) and, consequently, reduced sequestration in soil carbon pools (Lal 2005; Averill et al. 2014). This carbon persists in standing form, however, as beetle-killed trees can have a long residence time as snags. The decay dynamics of snags differs from that of deadwood (e.g., snags will dry out more quickly, and bark may fall while standing), and they may therefore differ in how their carbon is eventually cycled into soil carbon pools. Feedbacks between forest carbon sequestration ability, biotic disturbances, and climate change have not been well described and will require comprehensive assessment of variations in tree, snag, and deadwood pools and fluxes.

The overall diameter distribution of deadwood—representing an integration of wood remaining after more than 525 years of creation and decomposition—has a peak at about 40 cm diameter and quickly declines below diameters of about 25 cm (Fig. 5). This is despite the fact that inputs of deadwood were much more abundant at smaller diameter classes (Table 1). Most annual deposition (by number of pieces) was <40 cm diameter, but higher decomposition rates of smaller stems led to a smaller proportion of total deadwood biomass. That smaller diameter wood decays faster in closed-canopy forests is universally known (Harmon et al. 2020), but these data show the contrasting ecosystem function of large-diameter wood. Although large-diameter deadwood is not created as frequently, it remains in the ecosystem for long periods of time (Fig. 4), necessitating long periods of observation to detect changing dynamics (Birch et al. 2019a; Harmon et al. 2020; Davies et al. 2021). There was little directionality in the annual creation of deadwood (Fig. 2, Figs. S3–S12), although there was a higher amount of deadwood with an easterly orientation (Fig. 5). The absence of strong and consistent deadwood directionality may be due to the relatively flat site (Fig. 1). Alternatively, patterns in deadwood might only be created by significant storms that only occur so infrequently as to require long periods of observation. These long periods of observation are also useful in detecting past episodic mortality (i.e., Lutz et al. 2020; Lutz et al. 2021) or slightly higher rates of mortality on decadal scales (Birch et al. 2019b; Germain and Lutz 2020).

Large-diameter trees contributed 80% of the new deadwood flux (i.e., from trees alive at plot establishment to deadwood; Fig. 7), but only 58% of the static, long-term deadwood pool. The difference between these values likely indicates the proportion of deadwood originating from older, more decayed large-diameter snags that died long before establishment. With the exception of trees killed by saprophytes and windthrow, the transition process from snag to deadwood is lengthy. For example, no deadwood was produced in the 1 to 7 years following recorded tree mortality from suppression of large trees (Fig. 7), compared with vast amounts of deadwood produced by long-dead snags. This disparity may also be a function of antecedent tree fall from earlier phases of forest succession. Due to slow decomposition, deadwood pools reflect a prior forest structure (i.e., when the forest was younger and trees were smaller), and the largest trees may still be standing (indeed, many are). The relative contribution of large-diameter wood to deadwood may increase as more of the pioneering 525-year-old Pseudotsuga menziesii trees and snags begin to fall (Franklin et al. 2002).

Old-growth Tsuga–Pseudotsuga forests have perhaps the greatest amount of surface woody biomass (347 to 523 m3 ha−1 including snags and logs (Freund et al. 2015), approximately 91 to 141 Mg ha−1), generally equaled or exceeded only by Sequoia sempervirens forests (302 to 328 Mg ha−1, Sillett et al. 2019) and by Picea–Tsuga forests of the western coast of North America (Kramer et al. 2020). Our analysis of biomass pools in this 525-year-old Tsuga–Pseudotsuga forest reflects this, and they reveal the profound contribution of high-biomass temperate forests as globally important carbon stores. Even though snags and deadwood represented a minority of aboveground biomass in this forest (183 Mg ha−1), this deadwood comprises more carbon than exists in the live aboveground carbon pools of other ecosystems, including other forest types (Lutz et al. 2018; their Table 1). This deadwood carbon may be eventually transitory, but large pieces can persist for decades in many temperate forests, and much of their carbon will slowly cycle into more labile soil carbon pools. This renders the carbon stored in large-diameter deadwood stable on multi-decadal, and even centennial time scales (Fig. 6).

Total biomass stores at the plot level were high (664 Mg ha−1) and trees, snags, and deadwood comprised 481 Mg ha−1, 74 Mg ha−1, and 109 Mg ha−1, respectively (Table 1). This compares to Harmon et al. (2004) who found 790 Mg ha−1 in live trees, 58 Mg ha−1 in snags, and 84 Mg ha−1 in deadwood within the same study area using line-intercept methods for deadwood and a ≥10 cm diameter threshold (assuming a 50% ratio of carbon to biomass from their results). Similarly, Grier and Logan (1977) found an average of 717 Mg ha−1 total aboveground biomass in live trees and large shrubs, 25 Mg ha−1 in snags, and 190 Mg ha−1 in deadwood (using a diameter threshold of ≥15 cm for non-shrubs). This is also consistent with Smithwick et al. (2002), who found an average live tree biomass of 760 Mg ha−1, snag biomass of 25 Mg ha−1, and deadwood biomass of 148 Mg ha−1 in the Washington Cascades province (including some sampling done in this study site and assuming a 50% ratio of carbon to biomass from their results). The amount of live woody biomass in our study was well within the regional range (294–1200 Mg ha−1, mean 910 Mg ha−1) encompassing a wide range of other Pacific-Northwest forest types (Smithwick et al. 2002).

A considerable portion of the variation in aboveground live biomass between studies most likely represents differences in choice of allometric equations (i.e., Lutz et al. 2017b; Lutz et al. 2021). In this work, we have relied on the national-level (for the United States) equations of Chojnacky et al. (2014) for generalizability across the range of Pseudotsuga and Tsuga forests. However, old forests like the WFDP are characterized by complex crowns (Van Pelt et al. 2016; Van Pelt and Sillett 2008), and these crowns accumulate considerable biomass that is often only revealed through detailed tree measurements (i.e., in addition to DBH; Sillett et al. 2018). Biomass calculations for snags and deadwood should be much less variable among studies as most studies use the values of Harmon et al. (2008) and calculations based on piece geometry.

Structural heterogeneity has been a long-recognized feature of old-growth forests (i.e., Lutz et al. 2013; Michel et al. 2014; Furniss et al. 2017; Engone-Obiang et al. 2019), and that heterogeneity creates complex vertical habitat for a variety of arboreal taxa (i.e., Blomdahl et al. 2019). It is likely that the extreme heterogeneity in deadwood also creates a variety of terrestrial habitat niches. Using spatially explicit estimates, deadwood biomass varied by more than two orders of magnitude at the scale of 20 m. Previously, Harmon et al. (2004) reported a coefficient of variation of ~0.81 in deadwood biomass estimates along line transects (as inferred from their methods), compared to 0.69 in this study. Grier and Logan (1977) observed a range of 55 Mg ha−1 to 581 Mg ha−1 among the different communities using similar methods. This underscores the generally high level of biomass variation in these old forests, the differences that can arise due to different sampling methods, and the need for modernization (or at least standardization). Actual heterogeneity in deadwood biomass becomes unexplained variance when using transect sampling methods, and this variance is ignored when multiple transects are averaged to generate stand-level estimates (Cansler et al. 2019). Spatially explicit mapping methods such as these lead to more precise attribution of sources of variation, allowing more targeted efforts to improve aboveground carbon tracing (Janík et al. 2018; Lutz et al. 2020; Lutz et al. 2021).

Without taking the long-term nature of the broader lifecycle of woody biomass into account, variability in temperate old-growth forest carbon may seem unexplained and unpredictable. Relatively large amounts of biomass may suddenly transition from one pool to the next (e.g., as a result of wind events creating a pulse of mortality and snagfall) resulting in large variation in live biomass. However, given their slowly decomposing nature, biomass is potentially conserved for long periods of time thereafter in the form of snags and deadwood. The residence time in all three biomass pools, as well as the amount of biomass that transitions between pools, scales exponentially with tree size. We observed a weak inverse relationship between live biomass and dead biomass (Fig. S14) which, while potentially difficult to demonstrate conclusively, has long been held to be the case (Grier and Logan 1977). The spatially autocorrelated spread of saprophytic fungi (Holah et al. 1997; Hansen and Goheen 2000), fungal symbionts (e.g., Feng et al. 2021; Zhong et al. 2021), and soil processes (e.g., Tamjidi and Lutz 2020) likely influenced this spatial relationship and subsequent patterns of deadwood accumulation. Although one might expect to be able to use live biomass as a proxy for deadwood biomass, our observations suggest that this assumption may not hold true. In order to understand the underlying dynamics of this ecosystem, it is necessary to fully take into account all the trees: living, dead, standing, and fallen.

Recent declines in large-diameter trees (Lindenmayer et al. 2014; Lutz et al. 2009) cast the structural and microclimatic differences between young and old forests in sharp relief (Chen et al. 1999). If forests are managed for young, individually productive trees, their carbon is volatile. A disturbance event that causes considerable mortality (e.g., repeated harvesting) will cause that carbon to cycle quickly (Thornton et al. 2002). Conversely, if large trees are preserved, the carbon they contain is more stable even if the trees are killed (see also Körner 2017). Because there is so much deadwood originating from these large-diameter trees, it is important to preserve it for its undeniable contribution to carbon sequestration and ecological function (Janisch and Harmon 2002). Although a forest of small trees might have higher relative net primary productivity than an old-growth forest (Franklin et al. 1981), these forests sequester little carbon in trees and almost none in deadwood. Small-diameter trees constitute an unstable form of carbon sequestration that has potential for more rapid release. As mortality increases in forests following canopy closure, it is often assumed that decomposition begins to offset carbon sequestration, eventually reducing net primary production to negligible levels. Our results demonstrate, however, that once trees are large enough, their carbon is effectively sequestered for decades or centuries. Deadwood carbon persists on timescales that can match, or even exceed, the residence time of carbon stored in forest products. In the face of uncertainty, large-diameter trees are an invaluable carbon reservoir, whether they are alive or not.

Conclusion

Old-growth forests contain large stores of biomass in living trees, as well as in snag and deadwood biomass pools that are stable long after tree death. Ignoring biomass (or carbon) in deadwood pools can lead to substantial underestimations of sequestration and stability.

Availability of data and materials

All data necessary to recreate analyses is available from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- DBH:

-

Diameter at breast height, 1.37 m above the forest surface

- Deadwood:

-

Downed woody debris; here limited to down woody debris from the main stems of trees ≥10 cm diameter

- Snagfall:

-

When a snag (standing dead tree) falls to the ground leaving a stump <1.37 m tall

- WFDP:

-

Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot

References

Anderson-Teixeira KJ, Davies SJ, Bennett AC, Gonzalez-Akre EB, Muller-Landau HC, Wright SJ, Abu Salim K, Baltzer JL, Bassett Y, Bourg NA, Broadbent EN, Brockelman WY, Bunyavejchewin S, Burslem DFRP, Butt N, Cao M, Cardenas D, Clay K, Condit RS, Detto M, Du X, Duque A, Erikson DL, Ewango CEN, Fletcher CD, Gilbert GS, Gunatilleke N, Gunatilleke S, Hao Z, Hargrove WH, Hart TB, Hao B, He F, Hoffman FM, Howe R, Hubbell SP, Jansen PA, Jiang M, Kanzaki M, Kenfack D, Kinnaird MF, Kumar J, Larson AJ, Li Y, Li X, Liu S, Lum SKY, Lutz JA, Ma K, Maddalena D, Makana JR, Malhi Y, Marthews T, McMahon S, McShea WJ, Memiaghe H, Mi X, Mizuno T, Myers JA, Novotny V, de Oliveira AA, Orwig D, Ostertag R, den Ouden J, Parker G, Phillips R, Rahman A, Sri-ngernyuang K, Sukumar R, Sun IF, Sungpalee W, Tan S, Thomas SC, Thomas D, Thompson J, Turner BL, Uriarte M, Valencia R, Vallejo MI, Vicentini A, Vrška T, Wang X, Weiblen G, Wolf A, Xu H, Xugao W, Yap S, Zimmerman J (2015) CTFS-ForestGEO: A worldwide network monitoring forests in an era of global change. Glob Chang Biol 21(2):528–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12712

Averill C, Turner BL, Finzi AC (2014) Mycorrhiza-mediated competition between plants and decomposers drives soil carbon storage. Nature 505(7484):543–545 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12901

Berner LT, Law BE, Meddens AJH, Hicke JA (2017) Tree mortality from fires, bark beetles, and timber harvest during a hot and dry decade in the western United States (2003–2012). Environ Res Lett 12(6):065005 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6f94

Birch JD, Lutz JA, Hogg EH, Simard SW, Pelletier R, LaRoi GH, Karst J (2019a) Decline of an ecotone forest: 50 years of demography in the southern boreal forest. Ecosphere 10(4):e02698 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2698

Birch JD, Lutz JA, Simard SW, Pelletier R, LaRoi GH, Karst J (2019b) Density-dependent processes fluctuate over 50 years in an ecotone forest. Oecologia 191(4):909–918 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-019-04534-6

Bivand, R., T. Keitt, and B. Rowlingson (2019) rgdal: Bindings for the geospatial data abstraction library. R package version 1.4-8. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgdal

Bivand, R., and C. Rundel (2019) rgeos: Interface to geometry engine. R package version 0.5-2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgeos

Blomdahl EM, Thompson CM, Kane JR, Kane VR, Churchill DJ, Moskal LM, Lutz JA (2019) Forest structure predictive of fisher (Pekania pennanti) dens exists in recently burned forest in Yosemite, California, USA. For Ecol Manag 444:174–186 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.024

Cansler CA, Swanson ME, Furniss TJ, Larson AJ, Lutz JA (2019) Fuel dynamics after reintroduced fire in an old-growth Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Fire Ecol 15:16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-019-0035-y

Carvalhais N, Forkel M, Khomik M, Bellarby J, Jung M, Migliavacca M, Μu M, Saatchi S, Santoro M, Thurner M, Weber U, Ahrens B, Beer C, Cescatti A, Randerson JT, Reichstein M (2014) Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 514(7521):213–217 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13731

Chen J, Franklin JF, Spies TA (1995) Growing-season microclimate gradients from clearcut edges into old-growth Douglas-fir forests. Ecol Appl 5(1):74–86 https://doi.org/10.2307/1942053

Chen J, Saunders SC, Crow TR, Naiman RJ, Brosofske KD, Mroz GD, Brookshire BL, Franklin JF (1999) Microclimate in forest ecosystem and landscape ecology: variations in local climate can be used to monitor and compare the effects of different management regimes. BioScience 49(4):288–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313612

Chen J, Song B, Moeur M, Rudnicki M, Kibble DC, Shaw DMB, Franklin JF (2004) Spatial relationships of production and species distribution in an old-growth Pseudotsuga-Tsuga forest. For Sci 50(3):364–375 https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/50.3.364

Chojnacky DC, Heath LS, Jenkins JC (2014) Updated generalized biomass equations for North American tree species. Forestry 87(1):129–151. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpt053

Chu C, Lutz JA, Král K, Vrška T, Yin X, Myers JA, Abiem I, Alonso A, Bourg N, Burslem DFRP, Cao M, Chapman H, Condit R, Fang S, Fischer G, Gao L, Hao Z, Hau BCH, He Q, Hector A, Hubbell SP, Jiang M, Jin G, Kenfack D, Lai J, Li B, Li X, Li Y, Lian J, Lin L, Liu Y, Liu Y, Luo Y, Ma K, McShea W, Memiaghe H, Mi X, Ni M, O'Brien MJ, de Oliveira AA, Orwig DA, Parker G, Qiao X, Ren H, Reynolds G, Sang W, Shen G, Sui X, Sun I-F, Tian S, Wang B, Wang X-H, Wang X, Wang Y, Weiblen GD, Wen S, Xi N, Xiang W, Xu H, Xu K, Ye W, Zhang B, Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhu K, Zimmerman J, Storch D, Baltzer JL, Anderson-Teixeira KJ, Mittelbach GG, He F (2019) Direct and indirect effects of climate on richness drive the latitudinal diversity gradient in forest trees. Ecol Lett 22(2):245–255 https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13175

Das AJ, Larson AJ, Lutz JA (2018) Individual species-area relationships in temperate coniferous forests. J Veg Sci 29(2):317–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12611

Das AJ, Stephenson NL, Davis KP (2016) Why do trees die? Characterizing the drivers of background tree mortality. Ecology 97(10):2616–2627 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1497

Davies SJ, Abiem I, Abu Salim K, Aguilar S, Allen D, Alonso A, Anderson-Teixeira K, Andrade A, Arellano G, Ashton PS, Baker PJ, Baker ME, Baltzer JL, Basset Y, Bissiengou P, Bohlman S, Bourg NA, Brockelman WY, Bunyavejchewin S, Burslem DFRP, Cao M, Cárdenas D, Chang L-W, Chang-Yang C-H, Chao K-J, Chao W-C, Chapman H, Chen Y-Y, Chisholm R, Chu C, Chuyong G, Clay K, Comita LS, Condit R, Cordell S, Dattaraja HS, de Oliveira AA, den Ouden J, Detto M, Dick C, Du X, Duque Á, Ediriweera S, Ellis EC, Engone Obiang NL, Esufali S, Ewango CEN, Fernando ES, Filip J, Fischer GA, Foster R, Giambelluca T, Giardina C, Gilbert GS, Gonzalez-Akre E, Gunatilleke IAUN, Gunatilleke CVS, Hao Z, Hau BCH, He F, Ni H, Howe RW, Hubbell SP, Huth A, Inman-Narahari F, Itoh A, Janík D, Jansen PA, Jiang M, Johnson DJ, Jones A, Kanzaki M, Kenfack D, Kiratiprayoon S, Král K, Krizel L, Lao S, Larson AJ, Li Y, Li X, Litton CM, Liu Y, Liu S, Lum S, Luskin M, Lutz JA, Luu HT, Ma K, Makana JR, Malhi Y, Martin A, McCarthy C, McMahon SM, McShea WJ, Memiaghe H, Mi X, Mitre D, Mohamad M, Monks L, Muller-Landau H, Musili PM, Myers JA, Nathalang A, Ngo KM, Norden N, Novotny V, O’Brien MJ, Orwig D, Ostertag R, Papathanassiou K, Parker GG, Pérez R, Perfecto I, Phillips RP, Pongpattananurak N, Pretzsch H, Ren H, Reynolds G, Rodriguez LJ, Russo SE, Sack L, Sang W, Shue J, Singh A, Song G-ZM, Sukumar R, Sun I-F, Suresh HS, Swenson NG, Tan S, Thomas SC, Thomas D, Thompson J, Turner B, Uowolo A, Uriarte M, Valencia R, Vandermeer J, Vicentini A, Visser M, Vrska T, Wang X, Wang X, Weiblen GD, Whitfeld TJS, Wolf A, Wright SJ, Xu H, Yao TL, Yap SL, Ye W, Yu M, Zhang M, Zhu D, Zhu L, Zimmerman JK, Zuleta D (2021) ForestGEO: Understanding forest diversity and dynamics through a global observatory network. Biol Conserv 253:108907 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108907

Ellison AM, Buckley HL, Case BS, Cárdenas D, Duque AJ, Lutz JA, Myers JA, Orwig DA, Zimmerman JK (2019) Species diversity associated with foundation species in temperate and tropical forests. Forests 10(2):128 https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020128

Engone-Obiang NL, Kenfack D, Picard N, Lutz JA, Bissiengou P, Memiaghe HR, Alonso A (2019) Determinants of spatial patterns of canopy tree species in a tropical evergreen forest in Gabon. J Veg Sci 30(5):929–939 https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12778

Erb K-H, Fetzel T, Plutzar C, Kastner T, Lauk C, Mayer A, Niedertscheider M, Körner C, Haberl H (2016) Biomass turnover time in terrestrial ecosystems halved by land use. Nat Geosci 9(9):674–678. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2782

Erickson DL, Jones FA, Swenson NG, Pei N, Bourg NA, Chen W, Davies SJ, Ge X-J, Hao Z, Huang CL, Howe RW, Huang C-L, Larson AJ, Lum SKY, Lutz JA, Ma K, Meegaskumbura M, Mi X, Parker JD, Sun IF, Wright SJ, Wolf AT, Ye W, Xing D, Zimmerman JK, Kress WJ (2014) Comparative evolutionary diversity and phylogenetic structure across multiple forest dynamics plots: a mega-phylogeny approach. Front Genet 5:358 https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2014.00358

Feng J, Lutz JA, Guo Q, Hao Z, Wang X, Gilbert GS, Mao Z, Orwig DA, Parker GG, Sang W, Liu Y, Tian S, Cadotte MW, Jin G (2021) Mycorrhizal type influences plant density dependence and species richness across 15 temperate forests. Ecology 102(3):e03259 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3259

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, Editors (1993+) Flora of North America north of Mexico. 20+ volumes, New York and Oxford

Franklin, J. F., K. Cromack, W. Denison, A. McKee, C. Maser, J. Sedell, F. Swanson, and G. Juday (1981) Ecological characteristics of old-growth Douglas-fir forests. USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Experiment Station GTR-PNW-118.

Franklin JF, Spies TA, Van Pelt R, Carey AB, Thornburgh DA, Berg DR, Lindenmayer DB, Harmon ME, Keeton WS, Shaw DC, Bible K, Chen J (2002) Disturbances and structural development of natural forest ecosystems with silvicultural implications, using Douglas-fir forests as an example. For Ecol Manag 155(1-3):399–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00575-8

Freund JA, Franklin JF, Larson AJ, Lutz JA (2014) Multi-decadal establishment for single-cohort Douglas-fir forests. Can J For Res 44(9):1068–1078 https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2013-0533

Freund JF, Franklin JF, Lutz JA (2015) Structure of early old-growth Douglas-fir forests in the Pacific Northwest. For Ecol Manag 335:11–25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.08.023

Furniss TJ, Larson AJ, Kane VR, Lutz JA (2020) Wildfire and drought moderate the spatial elements of tree mortality. Ecosphere 11(8):e03214 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3214

Furniss TJ, Larson AJ, Lutz JA (2017) Reconciling niches and neutrality in a subalpine temperate forest. Ecosphere 8(6):Article01847. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1847

Germain SJ, Lutz JA (2020) Climate extremes may be more important than climate means when predicting species range shifts. Clim Chang 163(1):579–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02868-2

Grier CC, Logan RS (1977) Old-growth Pseudotsuga menziesii communities of a western Oregon watershed: biomass distribution and production budgets. Ecol Monogr 47(4):373–400. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942174

Halpern CB, Lutz JA (2013) Canopy closure exerts weak controls on understory dynamics: a 30-year study of overstory-understory interactions. Ecol Monogr 83(2):221–237 https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1696.1

Hansen EM, Goheen EM (2000) Phellinus weirii and other native root pathogens as determinants of forest structure and process in western North America. Annu Rev Phytopathol 38(1):515–539 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.515

Harmon ME, Bible K, Ryan MG, Shaw DC, Chen H, Klopatek J, Li X (2004) Production, respiration, and overall carbon balance in an old-growth Pseudotsuga–Tsuga forest ecosystem. Ecosystems 7:498–512 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-004-0140-9

Harmon ME, Fasth B, Woodall CW, Sexton J (2013) Carbon concentration of standing and downed woody detritus: Effects of tree taxa, decay class, position, and tissue type. For Ecol Manag 291:259–267 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.11.046

Harmon ME, Fasth BG, Yatskov M, Kastendick D, Rock J, Woodall CW (2020) Release of coarse woody detritus-related carbon: a synthesis across forest biomes. Carbon Balance Manag 15(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-019-0136-6

Harmon ME, Franklin JF (1989) Tree seedlings on logs in Picea-Tsuga forests of Oregon and Washington. Ecology 70(1):48–59 https://doi.org/10.2307/1938411

Harmon ME, Franklin JF, Swanson FJ, Sollins P, Gregory SV, Lattin JD, Anderson NH, Cline SP, Aumen NG, Sedell JR, Lienkaemper GW, Cromack KJR, Cummins KW (1986) Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv Ecol Res 15:133–302 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60121-X

Harmon ME, Woodall CW, Fasth B, Sexton J (2008) Woody detritus density and density reduction factors for tree species in the United States: a synthesis, General Technical Report NRS-29. Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Newton Square

Hicke JA, Allen CD, Desai AR, Dietze MC, Hall RJ, Hogg EH, Kashian DM, Moore D, Raffa KF, Sturrock RN, Vogelmann J (2012) Effects of biotic disturbances on forest carbon cycling in the United States and Canada. Glob Chang Biol 18(1):7–34 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02543.x

Holah JC, Wilson MV, Hansen EM (1997) Impacts of a native root-rotting pathogen on successional development of old-growth Douglas fir forests. Oecologia 111(3):429–433 https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050255

Janík, D., K. Král, D. Adam, T. Vrška, J. A. Lutz (2018) Smithsonian ForestGEO Dead Wood Census Protocol. Utah State University Digital Commons Paper 76. https://doi.org/10.26078/vcdr-y089

Janisch JE, Harmon ME (2002) Successional changes in live and dead wood carbon stores: implications for net ecosystem productivity. Tree Physiol 22(2-3):77–89 https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/22.2-3.77

Kane VR, Bakker JD, McGaughey RJ, Lutz JA, Gersonde R, Franklin JF (2010) Examining conifer canopy structural complexity across forest ages and zones with LiDAR data. Can J For Res 40(4):774–787. https://doi.org/10.1139/X10-064

Kane VR, Gersonde RF, Lutz JA, McGaughey RJ, Bakker JD, Franklin JF (2011) Patch dynamics and the development of structural and spatial heterogeneity in Pacific Northwest forests. Can J For Res 41(12):2276–2291 https://doi.org/10.1139/x11-128

Körner C (2017) A matter of tree longevity. Science 355(6321):130–131 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal2449

Kramer RD, Sillett SC, Kane VR, Franklin JF (2020) Disturbance and species composition drive canopy structure and distribution of large trees in Olympic rainforests, USA. Landsc Ecol 35(5):1107–1125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01003-x

Lal R (2005) Forest soils and carbon sequestration. For Ecol Manag 220(1-3):242–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.08.015

Larson AJ, Franklin JF (2010) The tree mortality regime in temperate old-growth coniferous forests – the role of mechanical damage. Can J For Res 40(11):2091–2103 https://doi.org/10.1139/X10-149

Larson AJ, Lutz JA, Donato DC, Freund JA, Swanson ME, HilleRisLambers J, Sprugel DG, Franklin JF (2015) Spatial aspects of tree mortality strongly differ between young and old-growth forests. Ecology 96(11):2855–2861 https://doi.org/10.1890/15-0628.1

Larson AJ, Lutz JA, Gersonde RF, Franklin JF, Hietpas FF (2008) Potential site productivity influences the rate of forest structural development. Ecol Appl 18(4):899–910 https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1191.1

Liaw A, Wiener M (2002) Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2(3):18–22 https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/

Lindenmayer DB, Laurance WF, Franklin JF, Likens GE, Banks SC, Blanchard W, Gibbons P, Ikin K, Blair D, McBurney L, Manning AD, Stein JAR (2014) New policies for old trees: averting a global crisis in a keystone ecological structure. Conserv Lett 7(1):61–69 https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12013

Lutz JA (2015) The evolution of long-term data for forestry: large temperate research plots in an era of global change. Northwest Sci 89(3):255–269 https://doi.org/10.3955/046.089.0306

Lutz JA, Furniss TJ, Germain SJ, Becker KML, Blomdahl EM, Jeronimo SMA, Cansler CA, Freund JA, Swanson ME, Larson AJ (2017a) Shrub communities, spatial patterns, and shrub-mediated tree mortality following reintroduced fire in Yosemite National Park, California, USA. Fire Ecol 13(1):104–126. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.1301104

Lutz JA, Furniss TJ, Johnson DJ, Davies SJ, Allen D, Alonso A, Anderson-Teixeira K, Andrade A, Baltzer J, Becker KML, Blomdahl EM, Bourg NA, Bunyavejchewin S, Burslem DFRP, Cansler CA, Cao K, Cao M, Cárdenas D, Chang L-W, Chao K-J, Chao W-C, Chiang J-M, Chu C, Chuyong GB, Clay K, Condit R, Cordell S, Dattaraja HS, Duque A, Ewango CEN, Fisher GA, Fletcher C, Freund JA, Giardina C, Germain SJ, Gilbert GS, Hao Z, Hart T, Hau BCH, He F, Hector A, Howe RW, Hsieh C-F, Hu Y-H, Hubbell SP, Inman-Narahari FM, Itoh A, Janík D, Kassim AR, Kenfack D, Korte L, Král K, Larson AJ, Li Y-D, Lin Y, Liu S, Lum S, Ma K, Makana J-R, Malhi Y, McMahon SM, McShea WJ, Memiaghe HR, Mi X, Morecroft M, Musili PM, Myers JA, Novotny V, de Oliveira A, Ong P, Orwig DA, Osterag R, Parker GG, Patankar R, Phillips RP, Reynolds G, Sack L, Song G-ZM, Su S-H, Sukumar R, Sun I-F, Suresh HS, Swanson ME, Tan S, Thomas DW, Thompson J, Uriarte M, Valencia R, Vicentini A, Vrška T, Wang X, Weiblen GD, Wolf A, Wu S-H, Xu H, Yamakura T, Yap S, Zimmerman JK (2018) Global importance of large-diameter trees. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 27(7):849–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12747

Lutz JA, Halpern CB (2006) Tree mortality during early forest development: a long-term study of rates, causes, and consequences. Ecol Monogr 76(2):257–275. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(2006)076[0257:TMDEFD]2.0.CO;2

Lutz JA, Larson AJ, Freund JA, Swanson ME, Bible KJ (2013) The importance of large-diameter trees to forest structural heterogeneity. PLoS ONE 8(12):e82784 http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082784

Lutz JA, Larson AJ, Furniss TJ, Freund JA, Swanson ME, Donato DC, Bible KJ, Chen J, Franklin JF (2014) Spatially non-random tree mortality and ingrowth maintain equilibrium pattern in an old-growth Pseudotsuga–Tsuga forest. Ecology 95(8):2047–2054. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0157.1

Lutz JA, Larson AJ, Swanson ME, Freund JA (2012) Ecological importance of large-diameter trees in a temperate mixed-conifer forest. PLoS ONE 7(5):e36131 http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036131

Lutz JA, Matchett JR, Tarnay LW, Smith DF, Becker KML, Furniss TJ, Brooks ML (2017b) Fire and the distribution and uncertainty of carbon sequestered as aboveground tree biomass in Yosemite and Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks. Land 6(10):1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6010010

Lutz JA, Struckman S, Furniss TJ, Birch JD, Yocom LL, McAvoy DJ (2021) Large-diameter trees, snags, and deadwood in southern Utah, USA. Ecol Process 10:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00275-0

Lutz JA, Struckman S, Furniss TJ, Cansler CA, Germain SJ, Yocom LL, McAvoy DJ, Kolden CA, Smith AMS, Swanson ME, Larson AJ (2020) Large-diameter trees dominate snag and surface biomass following reintroduced fire. Ecol Process 9:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00243-8

Lutz JA, van Wagtendonk JW, Franklin JF (2009) Twentieth-century decline of large-diameter trees in Yosemite National Park, California, USA. For Ecol Manag 257(11):2296–2307 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.03.009

Means J, Hansen H, Koerper G, Alaback P, Klopsch M (1994) Software for computing plant biomass – BIOPAK users guide, USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-GTR-340. USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland

Memiaghe HM, Lutz JA, Korte L, Alonso A, Kenfack D (2016) Ecological importance of small-diameter trees to the structure, diversity, and biomass of a tropical evergreen forest at Rabi, Gabon. PLoS ONE 11(5):e0154988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154988

Michel LA, Peppe DJ, Lutz JA, Driese SG, Dunsworth HM, Harcourt-Smith WEH, Horner WH, Lehmann T, Nightingale S, McNulty KP (2014) Remnants of an ancient forest provide ecological context for Early Miocene fossil apes. Nat Commun 5:3236. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4236

North M, Chen J, Oakley B, Song B, Rudnicki M, Gray A (2004) Forest stand structure and pattern of old-growth western hemlock/Douglas-fir and mixed-conifer forests. For Sci 50(3):299–311 https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/50.3.299

Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Fang J, Houghton R, Kauppi PE, Kurz WA, Phillips OL, Shvidenko A, Lewis SL, Canadell JG, Ciais P, Jackson RB, Pacala SW, McGuire AD, Piao S, Rautiainen A, Sitch S, Hayes D (2011) A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333(6045):988–993 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609

Parker GG, Harmon ME, Lefsky MA, Chen J, Van Pelt R, Weiss SB, Thomas SC, Winner WE, Shaw DC, Franklin JF (2004) Three-dimensional structure of an old-growth Pseudotsuga–Tsuga canopy and its implications for radiation balance, microclimate, and gas exchange. Ecosystems 7(5):440–453 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-004-0136-5

Pebesma EJ (2018) Simple features for R: Standardized support for vector data. R J 10(1):439–446 https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009

Pebesma EJ, Bivand RS (2005) Classes and methods for spatial data in R. R News 5(2) https://cran.r-project.org/doc/Rnews/

Privetivy T, Adam D, Vrška T (2018) Decay dynamics of Abies alba and Picea abies deadwood in relation to environmental conditions. For Ecol Manag 427:250–259 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.06.008

R Core Team (2020) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna https://www.R-project.org

Sillett SC, Van Pelt R, Carroll AL, Campbell-Spickler J, Coonen EJ, Iberle B (2019) Allometric equations for Sequoia sempervirens in forests of different ages. For Ecol Manag 433:349–363 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.11.016

Sillett SC, Van Pelt R, Freund JA, Campbell-Spickler J, Carroll AL, Kramer RD (2018) Development and dominance of Douglas-fir in North American rainforests. For Ecol Manag 429:93–114 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.07.006

Smithwick EAH, Harmon ME, Remillard SM, Acker SA, Franklin JF (2002) Potential upper bounds of carbon stores in forests of the Pacific Northwest. Ecol Appl 12(5):1303–1317 https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[1303:PUBOCS]2.0.CO;2

Spies TA, Franklin JF, Thomas TB (1988) Coarse woody debris in Douglas-fir forests of western Oregon and Washington. Ecology 69(6):1689–1702 https://doi.org/10.2307/1941147

Stenzel JE, Bartowitz KJ, Hartman MD, Lutz JA, Kolden CA, Smith AMS, Swanson ME, Larson AJ, Parton WJ, Hudiburg TW (2019) Fixing a snag in carbon emissions estimates from wildfires. Glob Chang Biol 25(11):3985–3994 https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14716

Taborska M, Privetivy T, Vrška T, Odor P (2015) Bryophytes associated with two tree species and different stages of decay in a natural fir-beech mixed forest in the Czech Republic. Preslia 87:387–401 http://www.preslia.cz/P154Taborska.pdf

Tamjidi J, Lutz JA (2020) Soil enzyme activity and soil nutrients jointly influence post-fire habitat models in mixed-conifer forests of Yosemite National Park, California, USA. Fire 3(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire3040054

Thorn S, Seibold S, Leverkus AB, Michler T, Müller J, Noss RF, Stork N, Vogel S, Lindenmayer DB (2020) The living dead: acknowledging life after tree death to stop forest degradation. Front Ecol Environ 18(9):505–512 https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2252

Thornton PE, Law BE, Gholz HL, Clark KL, Falge E, Ellsworth DS, Goldstein AH, Monson RK, Hollinger D, Falk M, Chen J, Sparks JP (2002) Modeling and measuring the effects of disturbance history and climate on carbon and water budgets in evergreen needleleaf forests. Agric For Meteorol 113(1-4):185–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(02)00108-9

Van Pelt R, Sillett SC (2008) Crown development of coastal Pseudotsuga menziesii, including a conceptual model for tall conifers. Ecol Monogr 78(2):283–311. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0158.1

Van Pelt R, Sillett SC, Kruse WA, Freund JA, Kramer RD (2016) Emergent crowns and light-use complementarity lead to global maximum biomass and leaf area in Sequoia sempervirens forests. For Ecol Manag 375:279–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.05.018

Vrška T, Privetivy T, Janík D, Unar P, Samonil P, Král K (2015) Deadwood residence time in alluvial hardwood temperate forests – a key aspect of biodiversity conservation. For Ecol Manag 357:33–41 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.08.006

Weed AS, Ayres MP, Hicke JA (2013) Consequences of climate change for biotic disturbances in North American forests. Ecol Monogr 83(4):441–470 https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0160.1

Wills C, Wang B, Fang S, Wang Y, Jin Y, Lutz JA, Thompson J, Pulla S, Pasion B, Germain SJ, Liu H, Smokey J, Su S-H, Butt N, Chu C, Chuyong G, Chang-Yang C-H, Dattaraja HS, Davies S, Ediriweera S, Esufali S, Fletcher CD, Gunatilleke N, Gunatilleke S, Hsieh C-F, He F, Hubbell S, Hao Z, Itoh A, Kenfack D, Li B, Li X, Ma K, Morecroft M, Mi X, Malhi Y, Ong P, Rodriguez LJ, Suresh HS, Sun I-F, Sukumar R, Tan S, Thomas D, Uriarte M, Wang X, Wang X, Yao TL, Zimmermann J (2021) Interactions between all pairs of neighboring trees in 16 forests worldwide reveal details of unique ecological processes in each forest, and provide windows into their evolutionary histories. PLoS Comput Biol In Press

Zhong Y, Myers J, Gilbert G, Lutz JA, Stillhard J, Zhu K, Thompson J, Baltzer J, He F, LaManna J, Davies S, Anderson-Teixeira K, Burslem D, Alonso A, Chao K-J, Wang X, Gao L, Orwig D, Yin X, Sui X, Su Z, Abiem I, Bissiengou P, Bourg N, Cao M, Chang-Yang C-H, Chao W-C, Chapman H, Chen Y-Y, Coomes D, Cordell S, de Oliveira A, Du H, Fang S, Giardina C, Hao Z, Hector A, Hubbell S, Janik D, Jansen P, Jiang M, Jin G, Kenfack D, Král K, Larson A, Li B, Li X, Li Y, Lian J, Lin L, Liu F, Liu Y, Liu Y, Luan F, Luo Y, Ma K, Malhi Y, McMahon S, McShea W, Memiaghe H, Mi X, Morecroft M, Novotny V, O'Brien M, Ouden J, Parker G, Qiao X, Ren H, Reynolds G, Sang W, Shen G, Shen Z, Song G-Z, Sun I-F, Tang H, Tian S, Uowolo A, Uriarte M, Wang B, Wang X-H, Wang Y, Weiblen G, Wu Z, Xi N, Xiang W, Xu H, Xu K, Butt N, Ye W, Yu M, Zeng F, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Zhu L, Zimmerman J (2021) Arbuscular mycorrhizal-associated trees drive the latitudinal beta-diversity gradient of tree communities in forests worldwide. Nat Commun In Press

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the field crews who gathered data, each individually acknowledged at http://wfdp.org. We thank the managers and staff of the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest for their logistical assistance and support. We thank the Wind River Field Station for installing WiFi in the Haunted House.

Funding

Funding was received from the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station (projects 1153, 1398, and 1423 to JAL), the National Science Foundation (DEB #1542681 to JAL and colleagues), and the Smithsonian Institution ForestGEO. Research was performed under a 5-year permit (2016–2020) from the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAL conceived the study. All authors performed field work. All authors contributed to analysis and writing, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

James A Lutz is the principal investigator for the Wind River Forest Dynamics Plot, http://wfdp.org, the Utah Forest Dynamics Plot, http://ufdp.org, and the Yosemite Forest Dynamics Plot, http://yfdp.org, each affiliated with the Smithsonian ForestGEO network.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Tables and Figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lutz, J.A., Struckman, S., Germain, S.J. et al. The importance of large-diameter trees to the creation of snag and deadwood biomass. Ecol Process 10, 28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-021-00299-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-021-00299-0