Abstract

Background

Soil microbial biomass, an important nutrient pool for ecosystem nutrient cycling is affected by several factors including climate, edaphic, and land-use change. Himalayan soils are young and unstable and prone to erosion and degradation due to its topography, bioclimatic conditions and anthropogenic activities such as frequent land-use change. Through this study, we tried to assess how soil parameters and microbial biomass carbon (MBC) of Eastern Himalayan soils originated from gneissic rock change with land-use type, soil depth and season. Chloroform fumigation extraction method was employed to determine MBC from different land-use types.

Results

Soil physical and chemical properties varied significantly with season, land-use and soil depth (p < 0.001). The maximum values of soil properties were observed in the rainy season followed by summer and winter season in all the study sites. Annual mean microbial biomass carbon was highest in the forest (455.03 μg g− 1) followed by cardamom agroforestry (392.86 μg g− 1) and paddy cropland (317.47 μg g− 1). Microbial biomass carbon exhibited strong significant seasonal difference (p < 0.001) in all the land-use types with a peak value in the rainy season (forest-592.78 μg g− 1; agroforestry- 499.84 μg g− 1 and cropland- 365.21 μg g− 1) and lowest in the winter season (forest − 338.46 μg g− 1; agroforestry – 320.28 μg g− 1 and cropland − 265.70 μg g− 1). The value of microbial biomass carbon decreased significantly with soil depth (p < 0.001) but showed an insignificant increase in the second year which corresponds to a change in rainfall pattern. Besides, land-use type, season and soil depth, soil properties also strongly influenced microbial biomass carbon (p < 0.001). Microbial quotient was highest in the agroforestry system (2.16%) and least in the subtropical forest (1.91%).

Conclusions

Our results indicate that land-use, soil depth and season significantly influenced soil properties and microbial biomass carbon. The physical and chemical properties of soil and MBC exhibit strong seasonality while the type of land-use influenced the microbial activity and biomass of different soil layers in the study sites. Higher soil organic carbon content in cardamom agroforestry and forest in the present study indicates that restoration of the litter layer through retrogressive land-use change accelerates microbial C immobilization which further helps in the maintenance of soil fertility and soil organic carbon sequestration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon cycle plays a vital role in shaping the earth’s atmosphere and climate systems. Soil microorganisms perform a major function in the soil carbon cycle of different ecosystems and regulating the ecosystem cycling. For the formation of the organic pool, soil microbial biomass carbon acts as a key indicator of soil organic carbon by decomposing organic matter and controlling nutrient dynamics which affect the primary productivity of the terrestrial ecosystem (Kara and Bolat 2008). During the last few decades, rapid global land-use change through the transformation of forest to cropland expanded fivefold (~ 3 to ~ 15 million km2 during 1700–2007) (Ramankutty et al. 2018). The Southeast Asian region also experienced 11.3% of the total forest cover loss, i.e., 29.3 × 1010 m2 during the period 2000 to 2014 (Zeng et al. 2018). Kanade and John (2018) also reported a decline in primary forest cover and increase in secondary forest and agriculture in Sikkim Himalaya by 30% and 16% of primary forest at an altitudinal range of 800–2200 m and 2200–2800 m, respectively.

Research on the effect of land-use change on soil ecosystem functioning due to human activities is necessary to study the soil processes in different land-use systems and to protect and regenerate the ability of soil to deliver ecosystem services (Van Leeuwen et al. 2017). Ecosystem functioning depends on the flux of carbon and other chemical nutrients, mediated by the microbial interaction in the soil, plant, and animal food web (Seneviratne 2015). Soil microbial biomass acts as a keystone biological driver to the ecosystem functioning (Singh and Gupta 2018). The unpredictable rise of climate and anthropogenic disturbances affects the microbial diversity in the ecosystems (Singh and Gupta 2018). Land-use types along with its geographical area, climate variability, soil properties, and the dominant vegetation composition are the key drivers in controlling microbial biomass carbon dynamics in different land-use types (Wardle 1992; Singh and Gupta 2018). Microbes are very sensitive to land-use change due to the differences in the litter composition and root turnover rates (Hooper and Vitousek 1998). The substrate quality of an ecosystem therefore plays a substantial role in the availability of microbes as it regulates the rate of microbial decomposition of freshly added and native soil organic carbon (SOC) (Jagadamma et al. 2014). Microbial biomass carbon in the soil contributed around 1–3% carbon to the total soil organic carbon (Dilly et al. 2003). Nutrient regulations to climate change through the carbon cycle by soil microbes are crucially important in carbon-climate reaction (Bardgett et al. 2008) due to the export of dissolved carbon through hydrological leaching and CO2 efflux by organic matter decomposition (Jenkinson et al. 1991; Davidson and Janssens 2006).

There is an increased interest for researchers for determining soil microbial biomass in ecosystem functioning (Azam et al. 2003) due to its ability to change soil quality following a land-use change (Bini et al. 2013). Study on soil microbial biomass carbon in the different land-use systems has been carried out globally by several researchers (Fang et al. 2014; Van Leeuwen et al. 2017; Bargali et al. 2018; Padalia et al. 2018; Singh et al. 2018; Soleimani et al. 2019). However, previous studies on microbial biomass carbon from Eastern Himalaya are limited only to forest (Maithani et al. 1996; Arunachalam et al. 1999; Devi and Yadava 2006) or more focussed on the jhum lands (Arunachalam and Pandey 2003; Ralte et al. 2005) and topsoil only (Sharma et al. 2004). But Eastern Himalaya, a biodiversity hotspot of the world, is a fragile region due to frequent land-use transformation/change through deforestation, land degradation, and disruption of the hydrological cycle (Tiwari 2008). Also, because of the high variation in the landscape of the Himalayas, the bioclimatic conditions change rapidly within a very short distance resulting in different soil properties and types (Baumler 2015). Microbial activities are significantly affected by the climate and human management (Rosenzweig et al. 2016), and the microbial carbon use efficiency varies across soil types due to several factors such as substrate quality and quantity, edaphic factors, stoichiometric constraint, and soil biodiversity (Lee and Schmidt 2014; Sinsabaugh et al. 2016). We hypothesize that land-use change alters the soil fertility and microbial biomass carbon that affects the soil organic carbon across soil depth. Hence, this study examined (i) the variance in soil characteristics and microbial biomass carbon in three different land-use types and (ii) the effect of season, land-use type, and soil depth on soil microbial biomass carbon.

Materials and methods

Study area and climate

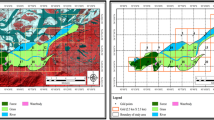

Three different subtropical land-use types located at Dzongu, North Sikkim, India, namely a subtropical forest (NF) (27° 31.550′ N and 88° 29.722′ E) at an altitude ranging from 1400 to 1700 m asl, a cardamom agroforestry system (AGF) (27° 31.311′ N and 88° 24.490′ E) position at an altitudinal range of 1350–1619 m asl, and paddy cropland (PC) (27° 31.445′ N and 88° 30.380′ E) situated at an elevation of 1200–1400 m asl, were chosen for the study (Fig. 1). The cardamom agroforestry system was converted from paddy cropland about 20 years ago. All the study sites are located in a sloped position (Table 1), but the paddy cropland has terraced beds on the surface. No tilling and chemical fertilizers have been added in any of the sites except for the paddy cropland where tilling has been carried out for the cultivation of paddy. Herbs from AGF were removed manually twice a year for the cultivation of large cardamom. Alnus nepalensis forms the dominant tree species both in the subtropical forest and cardamom agroforestry as it is favored by the farmers as a shade-providing tree due to its multiple uses. However, few other trees such as Ficus hookeri, Schima wallichii, Machilus edulis, Lyonia ovalifolia, Macaranga pustulata, Juglans regia, and Spondias axillaris were also present in both the study sites. Tree densities were higher in the forest than in the cardamom agroforestry. In the cardamom agroforestry system, only large cardamom (Ammomum subulatum) was planted along with trees on the sloped surface. Herbs are however present in the forest. All the study sites experienced a monsoonal climate with three distinct seasons, namely summer (March to May), rainy (June to October), and winter (November to February) seasons. However, summer is mild while winter is cold, and the rainy season is extremely wet. March and October are transitional months between winter and summer and rainy and winter, respectively. All the study sites have a mean air temperature that varied from 7 to 22 °C, relative humidity 31–95%, and an average annual rainfall of 2663 mm (2007–2016) (Meteorological Station Gangtok, Sikkim). Meteorological data of the study sites during the study period are shown in Fig. 2.

Geology

Geologically, the present study sites were located in the Lesser Himalayan Zone or sub-Himalayan region. This region has gneissic rocks derived from the Daling series (Saha 2013; Singh 2013). The National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning (NBSSLUP) classified soils of Sikkim as inceptisols (42.83%), entisols (42.52%), and mollisols (14.64%). All the study sites have gneissic rock origin. Subtropical forest and cardamom agroforestry have loamy soils while paddy cropland has clayey loam soil.

Soil sampling and analyses

Random soil samples were collected from five quadrats of 10 × 10 m established within each of the three land-use types in different seasons (i.e., summer, rainy, and winter) for two consecutive years. However, the distance between two quadrats in each of the study sites was at least 50 m apart. Soil samples were collected every alternate month, i.e., six times a year. A total of 60 soil samples from 15 soil pits from two different soil depths, viz., 0–15 and 15–30 cm, were taken from each of the land-use types by using a stainless steel soil corer (5 cm diameter) and mixed to form a composite sample for each depth. Roots, stones, and organic residues were removed from the samples, and each soil sample was divided into two parts. Half of each of the soil samples was stored at 4 °C to determine soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and the remaining half was air-dried for the determination of soil physical and chemical properties.

Soil moisture was analyzed by the gravimetric method and bulk density by oven drying of a known volume of fresh soil (80 °C). Air-dried soil samples were analyzed for texture by the hydrometer method (Allen et al. 1974), and pH was measured using an auto digital pH meter (1:5 soil distilled water suspension). Soil temperature was measured by using a soil thermometer. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was estimated by the colorimetric method (Anderson and Ingram 1993), and SOC stock was calculated following the procedure of Ravindranath and Ostwald (2008). The total nitrogen and available phosphorous in soil were determined by using the Kjeltec 8500 (FOSS) and ammonium molybdate stannous chloride method (Sparling et al. 1985), respectively.

Microbial biomass carbon was estimated by the chloroform fumigation and extraction method (Anderson and Ingram 1993) and calculated using the following formula (Vance et al. 1987):

MBC = EC × 2.64

where EC is the difference between C fumigated and unfumigated soil samples.

Data and statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 18.0. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used to compare the means of soil parameters, microbial biomass, and microbial quotients of different land-use types. The influence of land use and season, soil depth, and land use on the soil properties and microbial biomass carbon was studied by using the two-way ANOVA. Pearson’s multiple correlation analysis was carried out to determine the relationship between soil parameters and microbial biomass in different land-use types. Soil parameter data from different land-use types were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) by using R commander. All data are an average of five replicates ± SE of the composite soil samples.

Results

Soil properties

The physical and chemical properties of soil in three different land-use types are presented in Table 1. The physical and chemical properties of soil indicate the significant differences among land-use types and seasons (Table 2). However, no significant interaction between land use and season was observed for all the soil parameters except for microbial biomass carbon (MBC). The highest sand percentage was recorded in AGF, i.e., cardamom agroforestry (46.82%), followed by NF, i.e., subtropical forest (42.52%), and lowest in the PC, i.e., paddy cropland (38.56%). PC reported more silt and clay content (31.96% and 29.49%) than NF (30.82% and 26.67%) and AGF (30.11% and 23.08%) systems, respectively. Soil moisture content ranged from 22.00 to 33.67% in the NF, 24.33 to 35.00% in AGF, and 25.83 to 39.17% in PC with a maximum value in the rainy season and minimum in winter season in all the sites. Soil parameters vary across the different seasons; however, there is no consistent trend of seasonal variation across the land-use types (Table 2 of supplementary file). The physical and chemical properties of soil in the study sites differ significantly with soil depth (Table 2) and exhibit a decreasing trend across soil depth except for clay content and bulk density (Table 1). The bulk density varied from 0.62 to 0.81 g cm−1 in different land-use types and increased with soil depth. The maximum bulk density was recorded in NF (0.78 g cm−3) and lowest in the PC (0.70 g cm−3) while the soil temperature ranged from 7 °C (winter) to 21 °C (summer) across the sites.

Soil pH decreased with soil depth and ranged from 5.0 to 5.6 across the sites and soil depth (0–30 cm) with a maximum in the NF and minimum in PC (Table 1). The highest SOC, TN, AP, and SOC stock were in the NF (4.34%, 0.32%, 0.05%, and 40.99 Mg C ha−1, respectively) followed by AGF (4.09%, 0.30%, 0.04%, and 40.41 Mg C ha−1, respectively) and lowest in the PC (3.16%, 0.22%, 0.02%, and 34.16 Mg C ha−1, respectively) in the upper soil layer. However, silt content slightly increases in the subsurface soil layer of NF and AGF (Table 1). In the present study, SOC exhibits a negative significant relationship with bulk density and pH (p < 0.05) (Table 3). In the NF and AGF, the C/N ratio of soil increased with soil depth; however, it decreased slightly in the case of PC.

Soil microbial biomass carbon

Land-use types, season, and their interaction significantly influenced soil microbial biomass carbon in all the study sites (Table 2). Mean MBC varied from 592.78 ± 14.04 μg g−1 to 265.70 ± 7.33 μg g−1 in 0–30-cm soil layer across the seasons and land-use types (Table 4). An increase in soil depth showed a decreasing trend in MBC in all the three land-use systems while the highest concentration of MBC was in the rainy season and lowest in winter (Fig. 3). The microbial biomass carbon exhibited a significant difference (p < 0.001) with soil depth in all the land-use types (Table 2) however, it showed an insignificant increase in the second year. Soil of the NF (455.03 μg g−1) had the highest mean value of soil microbial biomass carbon, followed by AGF (392.86 μg g−1) and lowest in PC (317.47 μg g−1).

Microbial biomass quotient (MBC/SOC) %

Microbial biomass quotient ranged from 1.57 to 2.43% across the soil depth and land-use types (Table 5). The highest value of microbial biomass quotient was in the AGF followed by PC while the least was in NF. In the present study, the seasonal trend of microbial quotient was winter > summer > rainy season showing a slight decrease in the second year as well as with soil depth.

Correlation matrix and principal component analysis

The correlation matrix between the soil microbial biomass carbon with climatic and soil variables of three different land-use systems (Table 3) showed a strong significant positive relationship with all the parameters (p < 0.01) except for bulk density and soil pH where it is negatively significant (p < 0.05). SOC exhibited a positive significant relation with total N, available P, soil temperature, relative humidity, and microbial biomass carbon but showed negative significance with soil pH and bulk density (p < 0.05). The principal component analysis (PCA) of soil parameters in the different land-use types explained 49.0% variability in the first component and 26.5% in the second component (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The results of the present study revealed that the soil physical (soil moisture, bulk density, and pH) and chemical (C, N, and P) properties and microbial biomass carbon differ significantly in the three different land-use types with the highest in NF followed by AGF and PC except for soil moisture which exhibits a reverse trend. This is a result of the integrative response of topography and management practices adopted by each of the study sites. Adoption of terraced beds in sloped land of PC to conserve soil moisture, silt, and clay and removal of herbs from the sloped AGF to reduce competition with cardamom crop enhances soil erosion during heavy torrential rains resulting in a difference in the microclimate of the two sites which ultimately leads to an alteration of soil properties. Also, vegetation composition and amount of organic matter are different in the study sites which ultimately affect the microbial activity of soil. Several studies reported the influence of land use and change in soil management practices (George et al. 2013; Gonnety et al. 2013; Malik et al. 2018), topography, space and time, vegetation cover, climate, weathering processes, and microbial activities (Paudel and Sah 2003) on physico-chemical properties of soil. Bulk density (BD) of the present study (0.62–0.83 g cm−3) is within the range reported by Baumler and Zech (1994) (0.6–1.8 g cm−3), and it increases with a decrease in soil depth in all the land-use types. Our results agree with the report of several other studies from different land-use types of the world (Zhang et al. 2014; Francaviglia et al. 2017). Higher soil bulk density in the inner soil layers is due to less organic matter and weight of the overlying horizons (Grüneberg et al. 2014). The difference in BD of the different systems could be due to the difference in the particle size distribution of soils in the study sites, and a similar finding was reported by Dumig et al. (2006). A slight decrease in soil pH with soil depth in the present study coincides with abundant rainfall in the study sites which might lead to leaching of calcium and magnesium ions in the lower soil layers thereby leading to a decrease in pH of soil. Zhao et al. (2018) also reported a reduction in pH of subsoil due to leaching of calcium and magnesium ions in high rainfall areas which is in conformity with our report. Waterlogged soil condition due to paddy cultivation leads to more acidic soil in the cropland while the presence of low acidic soil in subtropical forest relates to the slope and topography of the forest which could not retain water or moisture for a long time leading to an increase in pH of soil. Several studies reported that soil pH is affected by slope, topography, terrain features, and topographic wetness index in the agricultural landscape and mountains (Chen et al. 1997) which agrees with our findings.

Our study indicated a difference in the sand, silt and clay content with land-use type, and soil depth (Table 2) which agrees with the report of Yusek and Yuksek (2011). However, contrasting results were reported from different land-use types (forest, grassland, cropland, and bare land) of Turkey (Evrendilek et al. 2004; Korkonc 2014) wherein no significant differences in the soil texture were observed with the change in land-use types and soil depth. Sand particles were highest in the AGF followed by NF and lowest in PC while clay and silt particles show a reverse trend with a maximum in PC and minimum in AGF. The reason for this reverse trend corresponds to the sloped position of the former two sites which enhances soil erosion in contrast to PC which has terraced beds on sloped land. Slightly higher sand in AGF than in NF could be due to the removal of herbaceous layers making the soil susceptible to erosion. The role of soil particle size distribution on vegetation, soil texture quality, and erosion has been reported by Aderonke and Gbadegesin (2013) which complies with our findings.

Soil moisture was higher in the PC (37.61%) than in NF and AGF soils (29.80% and 34.16%, respectively) because of higher clay content in the former. Such a relationship was established by many studies (English et al. 2005; Kara and Baykara 2014), but a reverse trend was reported by Amanuel et al. (2018).

Soil organic carbon (SOC) decreased with soil depth in all land-use types with maximum content in topsoil due to the availability of more organic matter from trees. The presence of trees continuously adds litter in the upper layer and increases root turnover (Kimmins 2004) which further enhanced SOC due to positive priming (Wu et al. 1993). Such a finding was reported by Soleimani et al. (2019) which conforms with our report. Also, annual carbon input in agricultural land through plant residue, a source of labile carbon, is lower than that of the natural forest leading to a low soil organic C (Hooker and Stalk 2008). Low SOC in the agricultural lands of the present study agrees with the reports of several studies (Huang and Song 2010; Reza et al. 2018). Higher total N in soils of the subtropical forest (NF) and AGF is related to the presence of the Alnus nepalensis nitrogen-fixing tree species, as a dominant tree in both the systems. Rothe et al. (2002) reported that the presence of N-fixing species increases soil total nitrogen content. A decrease in available phosphorus with soil depth in all the systems coincides with a low soil pH and that enhances P immobilization (Chase and Singh 2014). Soils of the present study indicate phosphorus limitation which could be due to the acidic nature of these soils. Transformation of the forest to cropland results in a reduction in the soil nutrients while the reverse process, i.e., PC → AGF or to a forest (NF), increased the nutrient content and soil organic carbon stock (PC → AGF ~ 5.25 Mg C ha−1 and AGF → NF ~ 1.43 Mg C ha−1) and lowers the acidity of the soil.

The microbial biomass carbon in soil of the present study ranged from 186.54 to 764.30 μg g−1 across the season, soil depth, and land use (Table 4), and this is within the reported range of tropical soils (106–2073 μg g−1) by Henrot and Robertson (1994). The highest MBC in the forest is due to the production of litter and deep root systems of the tree allowing more microbial activities than other agricultural land-use systems (Arunachalam et al. 1999). Low MBC in the agricultural systems is because of the different agricultural practices, resource availability, and plant composition (Van Leeuwen et al. 2017). A similar trend was reported by several studies in various ecosystems (Bardgett 2005; Soleimani et al. 2019). Furthermore, high moisture in the soil of paddy cropland (PC) due to waterlogging limits the microbial activity in the soil. A slightly higher MBC in the cardamom agroforestry (AGF) than that in PC is because of the presence of a litter layer in the former retaining soil moisture that promotes microbial activity. Wu et al. (2016) also reported a higher MBC in afforested soils with higher litter inputs which agree with our findings. A significant positive correlation between soil organic matter and soil microbial biomass (Table 3) in our study supports the findings of Chen et al. (2006) that soil MBC is highly influenced by soil organic matter present in different ecosystems. Such a result was supported by many researchers (Wang and Wang 2011; Chen et al. 2017; Padalia et al. 2018). Further, high soil N in the natural forest and cardamom agroforestry system is due to the presence of Alnus nepalensis which might result in a higher microbial biomass C in these sites. Wardle (1992) concluded that soil N showed more influence than C in organic C microbial immobilization in most of the systems which is consistent with our findings.

Distinct seasonal variations in soil MBC showing a peak value during the rainy (wet) season and a trough in the winter (dry) season (Fig. 3) in all the land-use types of the present study agree with the findings of previous studies from various tropical ecosystems (Devi and Yadava 2006; Iqbal et al. 2010; Patel et al. 2010). Seasonal variation of soil MBC is an indicator of immobilization and mineralization of soil carbon, and an increase in soil microbial biomass indicates immobilization, while a decrease denotes mineralization of nutrients (Yang et al. 2010). Warm and wet weathers during the rainy season accelerate litter decomposition as microbial activities and decomposition are at peak during this season thereby increasing the immobilization of nutrients by the microbes (Usman et al. 2000; Devi and Yadava 2010). Also, high relative humidity during the wet period accelerates the growth of fungi which further increases microbial biomass carbon (Acea and Carballas 1990). Least MBC during the dry and cold winter seasons coincides with a low temperature and less moisture in the soil leading to the death of microorganisms that release organic carbon, and freeze-thaw action can facilitate the decomposition of organic detritus and mineralization of carbon (Groffman et al. 2001). However, dry tropical deciduous forest (Singh et al. 1989) and humid subtropical forest of India (Arunachalam and Arunachalam 2000) show the highest microbial biomass C in summer and winter, respectively, indicating that the microbial biomass C is highly influenced by the species composition, location, elevation, and pattern of rainfall of the site.

Besides land-use type and season, another important factor controlling MBC is soil depth. MBC was more in the upper soil layer and less in the subsoil (Fig. 3) in all the land-use types. This pattern is because of lower carbon and nitrogen content in the lower subsoil and more organic matter in the top humus soil that promotes microbial activity. Previous studies on MBC across soil depth in various land-use types also reported similar findings (Fierer et al. 2003; Fall et al. 2012; Soleimani et al. 2019). In the present study, soil microbial biomass carbon was studied to a depth of 30 cm only, and due to this limitation of soil depth, the presence of the considerable amount of microbial biomass C in the deeper soil layers, i.e., 40–60 cm soil layer as reported by Soleimani et al. (2019), cannot be explored and further study is needed in this context from this region.

Principal component analysis (PCA) on soil physical and chemical properties of the three different land-use types of the present study (Fig. 4) shows 75.5% of the total variation along with the two principal components. PCA component F1 explained 49.0%, while the second component F2 explained 26.5% of variation. Change in the land-use type influenced the characterization capacity of soil parameters significantly. PC1 revealed that the microbial activity in NF is positively influenced by macro-elements, soil moisture, and temperature while soil pH exhibited an inverse relation with it. PC2 indicates that soil properties such as texture (silt, clay, and sand) and bulk density show strong influence with land use. However, sand and bulk density of soil play an important role in the cardamom agroforestry system, but silt and clay content show an inverse relation with sand.

Soil microbial quotient (MBC/SOC) of the present study agrees with the value of tropical forests, 1.5–5.3% (Luizao et al. 1992), and temperate forest soils, 1.8–2.9% (Vance et al. 1987), and those of agricultural soils (2–6%) reported by Brookes et al. (1985) (Table 5). The higher microbial quotient of the present subtropical forest than that of a humid subtropical forest of Northeast India, 0.7–1.77% (Maithani et al. 1996), indicates a higher microbial C immobilization. The microbial quotient varied significantly with the season and soil depth, and more immobilization of carbon in the winter season and least during the rainy season in all the land-use types is due to the availability of more substrate in winter. An increase in the microbial quotient with soil depth denotes the presence of more active carbon pools in the subsurface soil. Some studies reported that subsurface soil layers act as a store of microbial inoculation (Yi et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2009). A slight decrease in the microbial biomass quotient in the second year indicates a decrease in microbial immobilization of carbon and ultimately organic carbon in the soil which may be related to the change in environmental factors especially rainfall patterns in the second year (Fig. 2).

A higher microbial quotient in the cardamom agroforestry (AGF) indicates more carbon immobilization by the microbes from the organic substrates while the least microbial quotient in the forest (NF) may be a result of carbon mineralization from the microbes to support vegetation. Further, the exhibition of the highest microbial quotient ratio by the cardamom agroforestry system probably suggests better carbon immobilization capabilities of microbes in the agri-silviculture system than in the forest and cropland. Waid (1999) also reported that microbial diversity is affected by the type of vegetation, quantity, and chemical composition. Kara and Baykara (2014) stated that the MBC/SOC ratio is determined by the amount of labile organic matter and not by the size of the microbial biomass carbon, and their findings agree with our study. A previous study on the microbial quotient in different land-use types also reported a higher value of microbial quotient in agricultural soils than that of forest soils (Kara and Baykara 2014). Sparling et al. (1992) also suggested the percentage of organic C present as microbial biomass C as an indicator of changes in the quality of soil organic matter.

Conclusion

The results of the present study revealed that land use, season, and soil depth significantly influence the physical and chemical properties of soil and microbial biomass carbon. Organic matter or litter layer in tree-based systems increased SOC thereby helping in the restoration of better soil health and fertility. Microbial biomass carbon and soil parameters showed strong seasonality, and land-use type and soil depth strongly influenced the topsoil of all the study sites. Forest had the highest microbial biomass C and least microbial quotient while the reverse trend exhibited by the cardamom agroforestry system suggests better C immobilization in the agroforestry system. Low SOC and MBC in paddy cropland confirmed that the lack of organic matter inputs and intensive land management practices such as plowing and tillage of the soil decreased soil fertility and microbial activity. Hence, a tree-based agricultural system promotes microbial activity and soil fertility through the immobilization of nutrients by microbes.

Availability of data and materials

All data are included in the manuscript, and additional data are provided in the supplementary file.

Abbreviations

- MBC:

-

Microbial biomass carbon

- SOC:

-

Soil organic carbon

- NF:

-

Subtropical forest

- AGF:

-

Cardamom agroforestry

- PC:

-

Paddy cropland

- NBSSLUP:

-

National Bureau of Soil Survey and Planning

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- TN:

-

Total nitrogen

- AP:

-

Available phosphorous

- BD:

-

Bulk density

References

Acea MJ, Carballas T (1990) Principal components analysis of the soil microbial population of humid zone of Galicia (Spain). Soil Biol Biochem 22:749–759

Aderonke DO, Gbadegesin GA (2013) Spatial variability in soil properties of a continuously cultivated land. Afr J Agric Res 8(5):475–483

Allen SE, Grimshaw HM, Parkinson JA, Quarmby C (1974) Chemical analysis of ecological materials. Wiley, New York

Amanuel W, Yimer F, Karltun E (2018) Soil organic carbon variation in relation to land use changes: the case of Birr watershed, upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. J Ecol Environ 42(3):128–138

Anderson JM, Ingram J (1993) Tropical soil biology and fertility. A handbook of methods, 2nd edn. CAB, Oxford

Arunachalam A, Arunachalam K (2000) Influence of gap size and soil properties on microbial biomass in a subtropical humid forest of North-east India. Plant Soil 233:185–193

Arunachalam A, Pandey HN (2003) Ecosystem restoration of jhum fallows in northeast India: Microbial C and N along altitudinal and successional gradients. Restor Ecol 11(2):168–173

Arunachalam K, Arunachalam A, Melkania NP (1999) Influence of soil properties on microbial populations, activity and biomass in humid subtropical mountainous ecosystems of India. Biol Fertil Soils 30:217–223

Azam F, Farooq S, Lodhi A (2003) Microbial biomass in agricultural soils: determination, synthesis, dynamics and role in plant nutrition. Pak J Biol Sci 6:629–639

Bardgett R (2005) The biology of soils: a community and ecosystem approach. Oxford University Press Inc, New York

Bardgett RD, Freeman C, Ostle NJ (2008) Microbial contributions to climate change through climate change feedbacks. ISME J 2:805–814

Bargali K, Manral V, Padalia K, Bargali SS, Upadhayay VP (2018) Effect of vegetation type and season on microbial biomass carbon in Central Himalayan forest soils, India. Catena 171:125–135

Baumler R (2015) Soils. In: Miehe G, Pendry CA, Chaudhary RP (Eds.) Nepal: an introduction to the natural history, ecology and human environment in the Himalayas - a companion to the flora of Nepal. The Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh. pp. 126–134

Baumler R, Zech W (1994) Characterization of Andisols developed from non-volcanic material in Eastern Nepal. Soil Sci 158:211–217

Bini D, dos Santos CA, do Carmo KB, Kishino N, Andrade G, Zangaro W, Nogueira MA (2013) Effects of landuse on soil organic carbon and microbial process associated with soil health in Southern Brazil. Eur J Soil Biol 55:117–123

Brookes PC, Landman A, Pruden G, Jenkinson DS (1985) Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: a rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 17:837–842

Chase P, Singh OP (2014) Soil nutrients and fertility in three traditional landuse systems of Khonoma, Nagaland, India. Resour Environ 4:181–189

Chen C, Liu W, Jiang X, Wu J (2017) Effects of rubber-based agroforestry systems on soil aggregation and associated soil organic carbon: implications for land use. Geoderma 299:13–24

Chen FS, Zeng DH, Zhou B, Singh AN, Fan ZP (2006) Seasonal variation in soil nitrogen availability under Mongolian pine plantations at the Keerqin Sand Lands, China. J Arid Environ 67:226–239

Chen ZS, Hsieh CF, Jiang FY, Hsieh TH, Sun IF (1997) Relations of soil properties to topography and vegetation in a subtropical rain forest in southern Taiwan. Plant Ecol 132(2):229–241

Davidson EA, Janssens IA (2006) Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440:165–173

Devi NB, Yadava PS (2006) Seasonal dynamics in soil microbial biomass C, N and P in a mixed-oak forest ecosystem of Manipur, North-east India. Appl Soil Ecol 31(3):220–227

Devi NB, Yadava PS (2010) Influence of climate and litter quality on litter decomposition and nutrient release in sub-tropical forest of Northeast India. J For Res 21(2):143–150

Dilly O, Blume HP, Sehy U, Jimenez M, Munch JC (2003) Variation of stabilised, microbial and biologically active carbon and nitrogen in soil under contrasting land use and agricultural management practices. Chemosphere 52:557–569

Dumig A, Schad P, Kohok M, Beyerlein P, Schwimmer W, Koger-Knabner I (2006) A mosaic of nonallophanic Andosols, Umbrisols and Cambisols on rhyodacite in the southern Brazilian highlands. Geoderma 145:158–173

English NB, Weltzin JF, Fravolini A, Thomas L, Williams DG (2005) The influence of soil texture and vegetation on soil moisture under rainout shelters in a semi-desert grassland. J Arid Environ 63:324–343

Evrendilek F, Celil I, Kilic S (2004) Changes in soil organic carbon and other physical soil properties along adjacent Mediterranean forest, grassland, and cropland ecosystems in Turkey. J Arid Environ 59:743–752

Fall D, Diouf D, Zoubeirou AM, Bakhoum N, Faye A, Sall SN (2012) Effect of distance and depth on microbial biomass and mineral nitrogen content under Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. trees. J Environ Manage 95:S260–S264

Fang X, Wang Q, Zhou W, Zhao W, Wei Y, Niu L, Dai L (2014) Land use effects on soil organic carbon, microbial biomass and microbial activity in Changbai Mountains of Northeast China. Chin Geogra Sci 24(3):297–306

Fierer N, Schimel JP, Holden PA (2003) Variations in microbial community composition through two soil depth profiles. Soil Biol Biochem 35:167–176

Francaviglia R, Renzi G, Doro L, Parras-Alcantara L, Lozano-Garcia B, Ledda L (2017) Soil sampling approaches in Mediterranean agro-ecosystems. Influence on soil organic carbon stocks. Catena 158:113–120

George N, Killur RRB, Cornelio DL (2013) Land use conversion and soil properties in a lowland tropical landscape of Papua New Guinea. J Manajemen Hutan Tropika 1:39

Gonnety JT, Assémien EF, Guéi AM, Aya AN, Djina Y, Koné AW, Tondoh JE (2013) Effect of land-use types on soil enzymatic activities and chemical properties in semi-deciduous forest areas of Central-West Côte d’Ivoire. Biotechnol Agronomie Soc Environ 4:478–485

Groffman PM, Driscoll CT, Fahey TJ, Hardy JP, Fitzhugh RD, Tierney GL (2001) Effects of mild winter freezing on soil nitrogen and carbon dynamics in a northern hardwood forest. Biogeochemistry 56:191–213

Grüneberg E, Ziche D, Wellbrock N (2014) Organic carbon stocks and rates of forest soils in Germany. Glob Chang Biol 20:2644–2662

Henrot J, Robertson GP (1994) Vegetation removal in two soils of the humid tropics: effect on microbial biomass. Soil Biol Biochem 26:111–116

Hooker DT, Stalk MJ (2008) Soil carbon and nitrogen cycling in three semiarid vegetation types: response to an in situ pulse of plant detritus. Soil Biol Biochem 40:2678–2685

Hooper DU, Vitousek PM (1998) Effect of plant composition and diversity on nutrient cycling. Ecol Monogr 68:121–149

Huang J, Song C (2010) Effects of land use on soil water soluble organic C and microbial biomass C concentrations in the Sanjiang Plain in Northeast China. Acta Agric Scand Sect B-Soil Plant Sci 60(2):182–188

Iqbal J, Hu R, Feng M, Lin S, Malghani S, Ali IM (2010) Microbial biomass, and dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen strongly affect soil respiration in different land uses: a case study at Three Gorges Reservior Area, South China. Agric Ecosyst Environ 137(3-4):294–307

Jagadamma S, Mayes MA, Steinweg JM, Schaeffer SM (2014) Substrate quality alters the microbial mineralization of added substrate and soil organic carbon. Biogeosciences 11:4665–4678

Jenkinson DS, Adams DE, Wild A (1991) Model estimates of CO2 emissions from soil in response to global warming. Nature 351:304–306

Kanade R, John R (2018) Topographical influence on recent deforestation and degradation in the Sikkim Himalaya in India: implications for conservation of East Himalayan broadleaf forest. Appl Geogr 92:85–93

Kara O, Baykara M (2014) Changes in soil microbial biomass aggregate stability under different land uses in the Northeastern Turkey. Environ Monit Assess 186:3801–3808

Kara O, Bolat I (2008) The effect of different land uses on soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in Bartin Province. Turk J Agric For 32:231–288

Kimmins JP (2004) Forest ecology: a foundation for sustainable forest management and environment ethics in forestry, 3rd ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, p 611

Korkonc SY (2014) Effect of afforestation on soil organic carbon and other soil properties. Catena 123:62–69

Lee ZM, Schmidt TM (2014) Bacterial growth efficiency varies in soils under different land management practices. Soil Biol Biochem 69:282–290

Luizao RCC, Bonde TA, Rosswall T (1992) Seasonal variation of soil microbial biomass - the effects of clearfelling in a tropical rain-forest and establishment of pasture in the Central Amazon. Soil Biol Biochem 24:805–813

Maithani K, Tripathi RS, Arunachalam A, Pandey HN (1996) Seasonal dynamics of microbial biomass C, N and P during regrowth of a disturbed subtropical humid forest in northeast India. Appl Soil Ecol 4:31–37

Malik AA, Puissant J, Buckeridge KM, Goodall T, Jehmlich N, Chowdhury S, Gweon HS, Peyton JM, Mason KE, van Agtmaal M, Blaud A, Clark IM, Whitaker J, Pywell RF, Ostle N, Gleixner G, Griffiths RI (2018) Land use driven change in soil pH affects microbial carbon cycling processes. Nat Commun 9:3591

Padalia K, Bargali SS, Bargali K, Khulbe K (2018) Microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in relation to cropping systems in Central Himalaya, India. Curr Sci 115(9):1741–1749

Patel K, Kumar J, Kumar RN, Kumar B (2010) Seasonal and temporal variation in soil microbial biomass C, N and P in different types land uses of dry deciduous forest ecosystems of Udaipur, Rajasthan, Western India. Appl Ecol Environ Res 8:377–390

Paudel S, Sah JP (2003) Physicochemical characters of soil in tropical sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn.) forests in eastern Nepal. Himal J Sci 1(2):107–110

Ralte V, Pandey HN, Barik SK, Tripathi RS, Prabhu SD (2005) Changes in microbial biomass and activity in relation to shifting cultivation and horticultural practices in subtropical evergreen forest ecosystem of North-east India. Acta Oecol 28(2):163–172

Ramankutty N, Mehrabi Z, Waha K, Jarvis L, Kremen C, Herrero M, Rieseberg LH (2018) Trends in global agricultural land use: implications for environmental health and food security. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69:789–815

Ravindranath NH, Ostwald M (2008) Carbon inventory methods - handbook for greenhouse gas inventory, carbon mitigation and roundwood production projects. In: Global change research. Springer Verlag, Berlin, p 304

Reza SK, Baruah U, Nayak DC, Dutta D, Singh SK (2018) Effects of land-use on soil physical, chemical and microbial properties in humid subtropical Northeastern India. Natl Acad Sci Lett 41(3):141–145

Rosenzweig ST, Carson MA, Baer SG, Blair JM (2016) Changes in soil properties, microbial biomass, and fluxes of C and N in soil following post-agricultural grassland restoration. Appl Soil Ecol 100:186–194

Rothe A, Cromack K Jr, Resh SC, Makineci E, Son Y (2002) Soil carbon and nitrogen changes under Douglas-fir with and without red alder. Soil Sci Soc Am J 66:1988–1995

Saha D (2013) Lesser Himalayan sequences in Eastern Himalaya and their deformation: implications for Paleoproterozoic tectonic activity along the northern margin of India. Geosci Front 4:289–304

Seneviratne G (2015) Signal transduction in edaphic ecosystems governs sustainability. Agric Ecosyst Environ 210:47–49

Sharma P, Rai SC, Sharma R, Sharma E (2004) Effects of land-use change on soil microbial C, N and P in a Himalayan watershed. Pedobiologia 48:83–92

Singh AK (2013) Land resource management in North Eastern Himalayas. In: Arora S, Negi BS, Suraj B, Bali JS, Bharti VK (eds) Mountain people and environment. Soil Conservation Society of India, New Delhi, pp 65–83

Singh JS, Gupta VK (2018) Soil microbial biomass: a key soil driver in management of ecosystem functioning. Sci Total Environ 634:497–500

Singh JS, Raghubanshi AS, Singh RS, Srivastava SC (1989) Microbial biomass acts as a source of plant nutrients in dry tropical forest and savanna. Nature 338:499–500

Singh R, Bhardwaj DR, Pala NA, Kaushal R, Rajput BS (2018) Soil microbial characteristics in sub-tropical agroecostystems of North Western Himalaya. Curr Sci 115(10):1956–1959

Sinsabaugh RL, Turner BL, Talbot JM, Waring BG, Powers JS, Kuske CR, Moorhead DL, Shah JJF (2016) Stoichiometry of microbial carbon use efficiency in soils. Ecol Monogr 86:172–189

Soleimani A, Hosseini SM, Bavani ARM, Jafari M, Francaviglia R (2019) Influence of land use and land cover change on soil organic carbon and microbial activity in the forest of northern Iran. Catena 177:227–237

Sparling GP, Shepherd TG, Kettles HA (1992) Changes in soil organic C, microbial C and aggregate stability under continuous maize and cereal cropping and after restoration to pasture in soil from the Manawatu region, New Zealand. Soil Till Res 24:225–241

Sparling GP, Whale KN, Ramsay AJ (1985) Quantifying the contribution from the soil microbial biomass to the extractable P levels of fresh and air-dried soils. Aus J Soil Res 23:613–621

Tiwari PC (2008) Land use changes in Himalaya and their impacts on environment, society and economy: a study of the Lake Region in Kumaon Himalaya, India. Adv Atmos Sci 25(6):1029–1042

Usman S, Singh SP, Rawat YS, Bargali SS (2000) Fine root decomposition and nitrogen mineralization pattern in Quercus leucotrichophora and Pinus roxburghii forest in Central Himalaya. For Ecol Manag 131:191–199

Van Leeuwen JP, Djukic I, Bloem J, Lehtinen T, Hemerik L (2017) Effects of land use on soil microbial biomass, activity and community structure at different soil depths in Danube floodplain. Eur J Soil Biol 79:14–20

Vance ED, Brookers PC, Jenkinson DS (1987) An extraction method for measuring soil microbial C. Soil Biol Biochem 25:1646–1656

Waid SJ (1999) Does soil biodiversity depends upon metabolic activity and influences? Appl Soil Ecol 13:151–158

Wang Q, Wang S (2011) Response of labile soil organic matter to changes in forest vegetation in subtropical regions. Appl Soil Ecol 47(3):210–216

Wardle DA (1992) A comparative assessment of factors which influence microbial carbon and nitrogen levels in soils. Biol Rev 67:321–358

Wei Y, Zhang J, Yu Y (2009) Changes of soil microbial biomass carbon and microbial quotient in the restoration of degraded forest in Karst area of Guizhou Plateau. Res Agric Modernization 30(4):487–490

Wu J, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1993) Formation and destruction of microbial biomass during decomposition of glucose and ryegrass in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 25:1435–1441

Wu J, Zhang Q, Yang F, Lei Y, Zhang Q, Cheng X (2016) Afforestation impacts microbial biomass and its natural 13C and 15N abundance in soil aggregates in central China. Sci Total Environ 568:52–56

Yang K, Zhu J, Zhang M, Yan Q, Sun OJ (2010) Soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in forest ecosystems of Northeast China: a comparison between natural secondary forest and larch plantation. J Plant Ecol 3(3):175–182

Yi Z, Yi W, Ding M (2006) Vertical distribution of the concentrations of soil organic carbon, microbial biomass carbon and soil CO2 in Dinghushan Nature Reserve. Ecol Environ 15(3):611–615

Yusek T, Yuksek F (2011) The effects of restoration on soil properties in degraded land in semi-arid region of Turkey. Catena 84:47–53

Zeng Z, Estes L, Ziegler AD, Chen A, Searchinger T, Hua F, Guan K, Jintrawet AF, Wood E (2018) Highland cropland expansion and forest loss in Southeast Asia in the twenty-first century. Nat Geosci 11(8):556–562

Zhang L, Zhao R, Xie Z (2014) Response of soil properties and C dynamics to land-use change in the west of Loess Plateau. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 60(4):586–597

Zhao Z, Liu G, Liu Q, Huang C, Li H, Wu C (2018) Distribution characteristics and seasonal variation of soil nutrients in the Mun River Basin, Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:1818

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, for providing financial support in the form of project grant (DST/IS-STAC/CO2-SR-229/14(G)-AICP-AFOLU-IV). NT Lepcha thankfully acknowledged the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, for providing fellowship through the National Fellowship and Scholarship for Higher Education of ST (201617-NFST-2015-17-ST-SIK-1501 dated January 04, 2016).

Funding

The study is funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, in the form of a project grant (DST/IS-STAC/CO2-SR-229/14(G)-AICP-AFOLU-IV) to NBL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NTL collected and analyzed the data. NBL conceptualized and designed the study. Both authors wrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lepcha, N.T., Devi, N.B. Effect of land use, season, and soil depth on soil microbial biomass carbon of Eastern Himalayas. Ecol Process 9, 65 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00269-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00269-y