Abstract

Background

The oak tree (Quercus aegilops) comprises ~ 70% of the oak forests in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Besides its ecological importance as the residence for various endemic and migratory species, Q. aegilops forest also has socio-economic values—for example, as fodder for livestock, building material, medicine, charcoal, and firewood. In the KRI, Q. aegilops has been degrading due to anthropogenic threats (e.g., shifting cultivation, land use/land cover changes, civil war, and inadequate forest management policy) and these threats could increase as climate changes. In the KRI and Iraq as a whole, information on current and potential future geographical distributions of Q. aegilops is minimal or not existent. The objectives of this study were to (i) predict the current and future habitat suitability distributions of the species in relation to environmental variables and future climate change scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070); and (ii) determine the most important environmental variables controlling the distribution of the species in the KRI. The objectives were achieved by using the MaxEnt (maximum entropy) algorithm, available records of Q. aegilops, and environmental variables.

Results

The model demonstrated that, under the RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070 climate change scenarios, the distribution ranges of Q. aegilops would be reduced by 3.6% (1849.7 km2) and 3.16% (1627.1 km2), respectively. By contrast, the species ranges would expand by 1.5% (777.0 km2) and 1.7% (848.0 km2), respectively. The distribution of the species was mainly controlled by annual precipitation. Under future climate change scenarios, the centroid of the distribution would shift toward higher altitudes.

Conclusions

The results suggest (i) a significant suitable habitat range of the species will be lost in the KRI due to climate change by 2070 and (ii) the preference of the species for cooler areas (high altitude) with high annual precipitation. Conservation actions should focus on the mountainous areas (e.g., by establishment of national parks and protected areas) of the KRI as climate changes. These findings provide useful benchmarking guidance for the future investigation of the ecology of the oak forest, and the categorical current and potential habitat suitability maps can effectively be used to improve biodiversity conservation plans and management actions in the KRI and Iraq as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In Iraq, the natural forests, except for some riverine forests alongside the Euphrates and Tigris, are limited to the highlands of the northeast of the country known as the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) (Chapman 1950; Nasser 1984). The highlands comprise a chain of mountains extending from neighboring east (Iran) to the north (Turkey). Oak forests make up ~ 90% of the total forest cover in the KRI, and the remaining 10% comprises plantation, pine forest, riverine, and others (e.g., Pistacia khinjuk, Crataegus azaro), often mixed with the oak forests (Guest and Al-Rawi 1966; Nasser 1984). The predominant oak species is Q. aegilops, followed by Q. libani, Q. infectoria, and Q. macranthera. Except for Q. macranthera, the remainder is considered native to the region (Nasser 1984; Zohary 1973). Q. aegilops alone comprises ~ 70% of the oak forests (Shahbaz 2010). Being the dominant species, the trunk diameter, height, and crown width of the tree may reach 1 m, 20 m, and 7 m, respectively (Shahbaz 2010; Younis and Hassan 2019). Q. aegilops, apart from its ecological importance (e.g., as shelter and food for mammals and birds), also has economic and cultural importance—for example, as firewood, charcoal, timber, building material, and fodder for livestock (Chapman 1950; Mosa 2016; Nasser 1984; Nixon 2006; Van den Bergh and Kappelle 2006). Oak forests, specifically Q. aegilops, like the rest of the natural resources, have been degrading due to several factors by shifting cultivation and land use/land cover changes, population increase, civil war, and inadequate forest management policy (Nasser 1984). Wildfires (natural or man-made) during the scorching hot summer has also been reported (Chapman 1948; Rahimi et al. 2020). Furthermore, the economic sanctions by the United Nations Security Council between 1990 and 2000 significantly affected the oak forests in the KRI. Poverty and unemployment from the 10-year embargo (Alnasrawi 2001) obliged people to overexploit the forests mainly for firewood.

In Iraq and the KRI, studies on geographical distribution of oak trees are limited or not existent and often focused on examining the pedological characteristics (Abdullah et al. 2019), anatomical (Shahbaz et al. 2015), medicinal (Ghafour et al. 2010), and nutritional (e.g., acorn) (Rashid et al. 2014) components of the Quercus spp. Recently, Obeyed et al. (2020) used allometric equations to estimate the carbon sequestration capability of Q. aegilops in Duhok province. Similarly, using allometric equations, the total volume (i.e., trunk and branch volumes) of Q. aegilops trees was assessed (Younis and Hassan 2019). In Iran, El-Moslimany (1986) investigated the historical distribution and ecology of the Quercus forest using a pollen diagram. Others have investigated pollen and foliar morphology (Panahi et al. 2012), the influence of fire on oak forests (Heydari et al. 2017; Pourreza et al. 2014), regeneration factors of Quercus (Salehi et al. 2019), and genetic variation among the Quercus genus (Ardi et al. 2012). Climate variability and Q. cerris dieback relationship were investigated in Turkey and the Mediterranean regions (Di Filippo et al. 2010). The link between oak decline and pathogenic plant-damaging oomycetes (mold) in Turkey was investigated by Balci and Halmschlager (2003). Globally, numerous studies have been reported on various aspects of oak woodlands. Environmental gradient and morphological variations of Q. elliptica in Mexico and central America were evaluated by Maya-García et al. (2020). In the USA, the effects of global warming on the potential distribution and future status of six Quercus species was modeled (Ramírez-Preciado and Gasca-Pineda 2019). The decline of Quercus species in the southwest Germany is related to insufficient soil aeration and excessive CO2 concentration (Gaertig et al. 2002). In central-western Spain Quercus, geographical distribution scenarios relative to land use and abiotic stress-factors were modeled (Hernández-Lambraño et al. 2019). Phylogeographic and climatic indicators for the past and current status of the Quercus in China was assessed (Song et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2020).

Tree species distribution is known to depend mainly on climate variables (Woodward and Williams 1987), particularly temperature and water availability (e.g., precipitation) (Körner et al. 2016). The quantity and relative importance of these predictors vary over space and time for plant communities. For example, rain is the main climatic factor limiting the distribution of Q. aegilops and oak forests in the KRI (Guest and Al-Rawi 1966; Nasser 1984; Zohary 1973).

Under future climate change scenarios—for example, the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for its Fifth Assessment Report 5 (AR5), the quantity and pattern of the climate variables will change in the future due to greenhouse gases (e.g., CO2). This change, in turn, will influence the species distribution pattern, phenology, and forest ecosystems (Aitken et al. 2008; Jewitt et al. 2015; Trumbore et al. 2015; Urban 2015).

Species distribution models (SDMs) provide a unique opportunity to quantify and predict the relationship between species occurrence (records) and environmental variables (e.g., climate) (Hernández-Lambraño et al. 2019; Maya-García et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). Over the last two decades, various statistical models (e.g., generalized linear models (GLM; McCullagh 1984), generalized additive models (GAM; Hastie and Tibshirani 1990)), multivariate approach (e.g., ecological-niche factor analysis (ENFA; Hirzel et al. 2002), and machine-learning (e.g., maximum entropy (MaxEnt; Phillips et al. 2006) and random forest (RF; Breiman 2001)) approaches have been employed to understand the pattern of the link between species occurrence and environmental predictors. MaxEnt has strong prediction power in defining the geographical range of species, and it is dependent on presence-only data (Pearson et al. 2007; Phillips and Dudík 2008; Tsoar et al. 2007).

In the KRI Q. aegilops has been degrading by ongoing human-caused threats (e.g., cutting and clearing, land use/land cover change, and war-related operations), and these threats could increase as climate changes. Limited information exists on the current and potential distribution of the species in the KRI. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (i) predict the current and future habitat suitability distributions of the species in relation to environmental variables and future climate change scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070); and (ii) determine the most important environmental variables controlling the distribution of the species in the KRI. Addressing these objectives could provide invaluable information for conservation and management actions, not only for the oak but also for the associated biodiversity of the forests in the KRI and Iraq. This study by using MaxEnt, presence records of Q. aegilops, and current and future climate datasets aimed at achieving these objectives. This study was the first attempt investigating the spatial distribution of the species in the KRI and Iraq as a whole.

Materials and methods

Study area

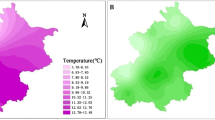

The study was conducted in Kurdistan Regional of Iraq (37°38′ N 46°35′ E) located in the northeast of the Republic of Iraq. KRI is made up of Sulaimani, Erbil, and Duhok (including Shekhan and Akre towns) provinces with an area of ~ 51520.76 km2 (Fig. 1). Iraq has four distinct geographical regions stretching gradually from the northeast to southeast: the highlands in the northeast (i.e., the KRI), the uplands (hilly and undulating areas; a transitional layer between the mountain ranges and desert), the desert, and alluvial plain (marshlands) (Bor and Guest 1968; Malinowski 2002). Anticlinal and synclinal features in the highlands created elevated peaks, valleys, cliffs, gorges, and rocky slopes. The altitude of the highlands, mostly inaccessible and remote, ranges between ~ 800 and 3544 m.a.s.l. (Sissakian et al. 2015). The annual precipitation ranges from 375 to 1200 mm, with an average temperature of ~ 35–40 °C and a minimum temperature ~ − 1 °C, indicating a very hot/dry summer and a wet and cool winter (https://gov.krd/english/).

Thus far, in Iraq and the KRI, only four distinct species of oak have been reported, namely, Q. aegilops , Q. libani, Q. infectoria, and Q. macranthera (Nasser 1984; Zohary 1973). The four species are found only in the mountain ranges of the KRI (Fig. 1).

Q. aegilops presence records data

The available records (i.e., geographic coordinates) of Q. aegilops were obtained from survey efforts in July 2017 and 2019, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (https://www.gbif.org/), and the literature (Abdullah et al. 2019; Shahbaz 2010; Younis and Hassan 2019). These data were collated and checked for quality (e.g., positional accuracy using both the survey efforts and Google Earth) and spatial representativeness (Morales et al. 2017). The original number of sample points (records) from the multiple sources was 57; after applying spatial filtering and removing duplicates, the number of points was reduced to 33. Spatial filtering of at least a 5-km distance was applied to reduce spatial auto-correlation (Boakes et al. 2010). Spatial filtering has the advantage of reducing sampling bias and accounts for the variability (or heterogeneity) of the terrain or study site (Radosavljevic and Anderson 2014). The filtering, in turn, results in producing more reliable models (i.e., reduce model over-fitting and may enhance transferability) (Boria et al. 2014; Kramer-Schadt et al. 2013; Townsend Peterson et al. 2007). Spatial filtering and quality checking were performed using ArcGIS 10.3. (ESRI, Redland, CA, USA) and extended using SDMtoolbox 2.4. (Brown 2014).

Environmental variables

The extent of the available records of Q. aegilops data was within the highland boundary (i.e., KRI), which mainly encompasses three provinces in the northeast of Iraq—Sulaimani, Erbil, and Duhok (Fig. 1). Besides the highlands, the oak naturally does not occur in other parts of Iraq. Similarly, the climate variables were also extracted according to the spatial extent of the presence records distribution and the KRI boundary as the potential extent of the target species. Previous studies have emphasized on training models based on the geographical extent of the distribution of the species (Elith et al. 2010; Soberon and Peterson 2005).

Model building in this study was based on selected climatic, edaphic, and topographic predictors (Table 2). These variables are key drivers influencing the distribution of plant species (Yi et al. 2018). This study acknowledges the importance of landscape variables—for example, edge density, total core area, and human footprint in model building. Unfortunately, due to lack of reliable data, these were not considered in the current work. The initial climatic variables included 19 bioclimatic variables for each the current (i.e., average for the years 1970–2000) and for the future scenarios (i.e., 2070s). Those datasets were obtained from the World Climate database (Hijmans et al. 2005) (www.worldclim.org). For the future climate scenario, the widely used (Ebrahimi et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018) global circulation model of the Beijing Climate Centre-Climate System Modelling 1.1 (BCC-CSM1.1) was employed. This dataset comprise the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 (Van Vuuren et al. 2011) and 8.5 (Riahi et al. 2011) for the time window 2070, released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report 5 (AR5). The RCP 2.6 and RCP 2.8 indicate the lowest and highest greenhouse gas concentration scenarios for 2070, respectively. The initial edaphic variables (e.g., soil pH, soil moisture, and soil carbon) were obtained from the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE) (http://www.sage.wisc.edu/atlas/index.php). The edaphic parameters are indirect measurement from global and/or regional inventories (i.e., they are model-based) and the scale of the original dataset is 0.5° × 0.5° (Task 2000; Willmott and Matsuura 2001). Topographic variables were derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) from the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Consortium for Spatial Information (http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/srtmdata/). From the SRTM, the DEM (digital elevation model), slope and aspect were derived. Preprocessing and variable spatial rescaling to ~ 1 km (Hu et al. 2015) were accomplished within the ArcGIS 10.3 platform. The slope and aspect in degree units were calculated from the DEM.

The original number of environmental variables was 25; of these, only 10 variables (Table 1) were used in model building due to high spatial correlation (collinearity) between the variables. High correlation variables inflate (or over-fit) the model outputs, thus providing misleading conclusions (Dormann et al. 2013; Graham 2003). Nevertheless, predictor selection requires careful thought and local knowledge of the climatic conditions and probably the physiology of the target species (Elith and Leathwick 2009). To address the issue of collinearity, a conditional threshold approach was used (Dormann et al. 2013) that retained only predictors with Pearson’s pairwise correlation, where Pearson’s |r | ≤ 0.8 (Dormann et al. 2013; Syfert et al. 2013) was used for model building (Tables 1 and 2). Pearson’s pairwise correlation analysis for the predictors was performed using ArcGIS 10.3 and SDMtoolbox extension (Brown et al. 2017).

Model building

Model choice in this study was based on the Q. aegilops presence records and predictive capability of the model. MaxEnt (Phillips et al. 2006) has been reported to have adequate predictive power, and it is one of the few presence-only-dependent models producing results comparable to presence-absence models (Aguirre-Gutiérrez et al. 2013; Duan et al. 2014; Dudík et al. 2007; Elith et al. 2006; Wisz et al. 2008). MaxEnt is a machine learning algorithm that could address various ecological questions (Merow et al. 2013). For example, it can map (interpolate) the potential habitat suitability distribution of a target species as the function of certain, often pre-selected, environmental conditions (Phillips et al. 2006).

Model building was initiated by randomly partitioning Q. aegilops presence data-points into 70% and 30% to validate and test the model, respectively. Model replicate choice was set to 10 with 500 iterations of the algorithm (maximum entropy). The 10 model-replicate choices produced an average suitability map of the probability of occurrence of the target species. The selected background points were set to 500, which was necessary to adjust for the presence records (Elith and Leathwick 2009) of Q. aegilops (n = 33). Additionally, a bias file, generated in ArcGIS 10.3, was also used to account for the distribution of the target species rather than the sampling effort distribution (Kramer-Schadt et al. 2013). The MaxEnt default settings for the regularization multiplier (β), which is 1, was selected in the model building, following Phillips et al. (2006) and Merow et al. (2013). The regularization multiplier fine tunes the model complexity and simplicity—for example, decreasing the number to below 1 increases the model complexity and increasing the number to above 1 simplifies the model (Merow et al. 2013). To assess the predictor’s relative importance and contribution to the probability of the habitat distribution of Q. aegilops, the Jackknife test was selected (Phillips 2005). Furthermore, the logistic output format with the ‘maximum test sensitivity plus specificity Logistic threshold’ for delineating the continuous map was applied (Liu et al. 2013). The threshold dependent value of 0.39 was used for delineating the probability of habitat suitability (i.e., ≥ 0.39) and unsuitability (i.e., < 0.39) distribution of Q. aegilops (i.e., probability of occurrence) (Jiménez-Valverde and Lobo 2007). The threshold value was based on the average of the 10 models (10 replicates). The delineation was achieved by reclassifying the continuous map into four classes, according to the following categories: 0–0.39 (unsuitable); 0.39–0.49 (lowly suitable); 0.49–0.74 (moderately suitable); 0.74–0.99 (highly suitable). This procedure was performed by using spatial analyst tools in ArcGIS 10.3.

Model evaluation

To test the efficiency of the model, two widely acceptable evaluation metrics were used: (i) the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) (Hanley and McNeil 1982; Phillips et al. 2017) and (ii) the True Skill Statistics (TSS) (Allouche et al. 2006). A high AUC value (e.g., 0.7–1.0) represents very good discriminatory power of the model in predicting a better than random guess. By contrast, the performance of the model reduces with a decreasing AUC value (e.g., an AUC value < 0.5–0.0 represents poor performance) (Fielding and Bell 1997; Phillips et al. 2017). The same argument is valid for the TSS value, which ranges between − 1 and 1 (Allouche et al. 2006). The metrics were calculated using both the MaxEnt model outputs and equations defined by Allouche et al. (2006) as (TSS = sensitivity (true positive rate) + specificity (true negative rate) – 1).

Change detection analysis between current and future habitat distributions

The habitat suitability maps were then used to quantify current and future distribution changes predicted from the model. The distribution changes for Q. aegilops in the KRI were quantified as follows: (i) Range expansion (i.e., the probability of new areas that would be suitable for Q. aegilops in 2070); (ii) Unsuitable (i.e., areas that are unsuitable under current environmental factors and would stay unsuitable in the future (2070); (iii) No change (i.e., areas already occupied by Q. aegilops and will stay occupied in the future); (iv) Range contraction (areas of Q. aegilops that would shift or shrink in the future). All the analyses were performed with a spatial toolbox available within the ArcGIS 10.3 environment.

Magnitude and direction of distributional changes

To provide a clear picture of the distributional changes (shifts) between the current and future scenarios, the centroid (i.e., ‘arithmetic mean’ of the species records (latitude and longitude) across its range (spatial extent)), was calculated across time. This analysis was performed using a GIS tool developed by Brown et al. (2017) to identify the centroid of the distribution changes of the suitable areas. This tool deciphers the core distributional shifts of the target species by reducing the spatial records into a single point (centroid) together with attributes of the magnitude and direction by creating a vector shape file (Brown et al. 2017).

Results

Predictor’s relative contribution and importance to the probability of distribution

The relative contribution (%) of the annual precipitation (Bio12) was 45.4%, suggesting Bio12 alone contributed significantly to the distribution probability of Q. aegilops in the KRI. Similarly, aspect, annual mean temperature (Bio1), and slope significantly contributed to the distribution by 19.9%, 13.5%, 15.1%, respectively. These four predictors collectively contributed to nearly 94% of the total number of predictors (Table 3). By contrast, mean diurnal range temperature (Bio2), temperature seasonality (Bio4), and soil pH demonstrated the lowest contribution to the distribution of Q. aegilops in the KRI (Table 3). Moreover, the Jackknife test to regularize training gain demonstrated that Bio12, slope, aspect, and Bio1 contained more information in determining the distributional pattern of Q. aegilops in the KRI than other predictors (Fig. 9 in Appendix).

Permutation importance indicates the subsequent roles of variable values, which permute randomly on the training portion of the presence data and the background points. For each turn (i.e., for each variable), this process is repeated and in turn the model is reevaluated using the AUC predictor gain (Phillips et al. 2006).

Model performance and current habitat suitability distribution

Model performance was evaluated using both AUC and TSS Metrics (methodology section). The model demonstrated very good discriminatory power of AUC = 0.8 ± 0.1 and TSS = 0.8 ± 0.2. In other words, the models were successful in predicting the suitable habitat distribution of Q. aegilops in the KRI under the selected environmental predictors. The model predicted that ~ 8652.2 km2 (16.7%) of the total study area of 51520.8 km2 was a suitable habitat of Q. aegilops. The remaining portion of ~ 42868.6 km2 (83.2%) was predicted as unsuitable (Table 4; Fig. 2). The suitable habitat area (i.e., 8652.2 km2), as predicted by the model, was divided into lowly suitable (area 5249.2 km2 (10.2%)), moderately suitable (area 2653.8 km2 (5.2%)), and highly suitable (area 749.2 km2 (1.5%)). This level of detail could assist conservation efforts more realistic and plausible (Table 4; Fig. 2).

Future habitat suitability distribution

Future results demonstrated that the spatial distribution of Q. aegilops would be reduced under both RCP scenarios in 2070. Thus, the proportion of the habitat suitability categories would be reduced and, instead, the unsuitability category would increase in 2070. For example, the total suitable areas (all categories) would be reduced by 2% (8652.2 to 7588.6 km2) and 1.5% (8652.2 to 7893.3 km2) in 2070 for the RCP2.6 and RCP8.5, respectively (Table 4; Figs. 3 and 4). Lowly suitable and moderately suitable categories would be reduced by 1.4% and 0.9% under the RCP2.6 and RCP8.5 scenarios, respectively. Surprisingly, the highly suitable category would be increased by 0.3% and 0.4% under the 2070 scenarios, respectively. By contrast, the unsuitable category area, under both RCP scenarios, would increase by 2.0% and 1.5%, respectively, in 2070, suggesting a spatial shift in the distribution of Q. aegilops in the KRI (Table 4; Figs. 3 and 4).

Change detection analysis between current and future habitat distribution

The distributional change analysis over space and time under the climate change scenarios (RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070) indicated that Q. aegilops would expand and contract spatially. The contraction magnitude was demonstrated to be higher than the expansion magnitude. For example, under RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070, the Q. aegilops ranges contracted by 3.6% (1849.7 km2) and 3.2% (1627.1 km2), respectively. However, the ranges expanded only by 1.5% (777.0 km2) and 1.65% (848.0 km2), respectively (Table 5; Figs. 5 and 6).

Magnitude and direction of distributional changes

The current habitat suitability distribution centroid of Q. aegilops stands at the 44°38′28.503′′ E and 36°14′39.922′′ N geographical position. Under the RCP8.5 2070 and RCP2.6 2070 climate change scenarios (i.e., 50 years from now), the current distribution centroid position would shift to new distribution centroids, 44°34′26.321′′ E; 36°17′48.471′′ N and 44°39′0.877′′ E;36°14′2.435′′ N, respectively. The magnitude and direction of the centroid shift under RCP8.5 2070 were stronger and demonstrated distributional change direction toward northwest (Fig. 10 in Appendix).

Discussion

The most important predictor relatively (by 45.4%) controlling the distribution of Q. aegilops in the KRI, as demonstrated by the model, was annual precipitation (Bio12). The optimal annual precipitation between 850 and 1042 mm determines the current habitat suitability of the species in the KRI. This amount of precipitation in KRI is often associated with high altitude (mountain areas) (Nasser 1984). These results concur with previous studies, suggesting rain as the key ecological factor limiting the distribution of the oak forests in the northeast of Iraq (KRI) (Guest and Al-Rawi 1966; Nasser 1984; Zohary 1973). However, the amount of rain and optimal range was not determined by these studies. Intuitively, this result was not supersizing because, in the arid and semi-arid eco-regions, the availability of water could be the key limiting factor for plant growth and development. However, in the temperate regions, temperature (sun light) could be the limiting factor for plant distribution and growth (Junttila and Nilsen 1993). The physiological and biochemical processes of plants are highly associated with water availability, particularly in semi-dry areas (Wang et al. 1998). Soil moisture and leaf anatomy during the dry season might also play a significant role in the widespread distribution and development of Q. aegilops in the KRI. For example, in the KRI, including in the mountains, the rate of rainfall is close to 0 from June to September (El-Moslimany 1986). However, the Quercus species, particularly Q. aegilops, thrived. The heat tolerance factor could be one of the reasons for its dominance compared with other Quercus species (Shahbaz et al. 2015). The mountains in the KRI receive a significant amount of precipitation during September onwards compared with the low lands. However, this finding does not necessarily infer the relative importance of other factors, such as biological interactions (including human factors), geology, and dispersal, which do not participate in the distribution of Q. aegilops. For example, villagers in the mountain ranges depend mainly on Q. aegilops fodders for livestock, and harvesting firewood during winter seasons. Apart from that pollarding and harvesting non-wood forest products—for example, oak acorns are common practices (Ghahramany et al. 2018). These traditional practices may influence the distribution of the species in the KRI. Moreover, the role of various mammal and bird species (e.g., squirrels, ravens, jays and magpies available in the KRI (Hatt 1959; Salim et al. 2010)) should be considered as biological factors in the dispersal of the species. In addition, the anticlinal and synclinal features in the highlands created elevated peaks, valleys, cliffs, gorges, and rocky slopes, which, in turn, create a network of natural water lines, could play a role in the species distribution.

The distributional change analysis under the climate change scenarios (i.e., RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070) demonstrated the probability of the distribution of Q. aegilops in the KRI would reduce by 3.6% (1849.7 km2) and 3.16% (1627.1 km2) respectively. By contrast, the model demonstrated the species expand in range only by 1.5% (777.0 km2) and 1.7% (848.0 km2) respectively (Table 5; Figs. 5 and 6). More specifically, the highly suitable category areas would expand from current 749.2 km2 (1.5%) to 889.7 (1.7%) and 931.4 km2 (1.8%) under the climate change scenarios, respectively (Table 4). In contrast, lowly and moderately suitable categories would contract. This increasing and decreasing trend suggests a spatial shift in the distribution of Q. aegilops. Therefore, conservation plans and actions should focus on the areas where the species is most vulnerable (i.e., lowly and moderately suitable categories).

Future climate change scenarios (i.e., RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070) indicated the best and worst-case anthropogenic-caused greenhouse gases (concentration), respectively. Under both scenarios, the amount of precipitation in the KRI in 2070 would decrease over space. For example, annual precipitation would be reduced from a maximum of 1042 mm (current) to 1031 mm (RCP2.6) and 843 mm (RCP8.5). The reduction in the precipitation would influence the spatial distributional change of Q. aegilops. The direction of the distributional change would move towards northwest (i.e., Erbil and Duhok). However, the amount of precipitation would decrease relatively in the southeast (i.e., in Sulaimani) and, conversely, it would stay stable or within the optimal range in the northeast. This argument is also valid for temperature-related variables—for example, the annual mean temperature, which also contributes significantly to the distribution probability of Q. aegilops, increased by around 3.7 °C in 2070 under the CRP2.8 scenario. The spatial increase in the temperature in some areas would mean less rain and more drought. The core distributional shift (expansion) of Q. aegilops in the KRI towards the northeast indicates that the species prefer cooler areas with higher annual precipitation. The Erbil and Duhok mountain areas receive more annual rainfall (i.e., more elevated peaks and, thus, more mountainous) than that of the Sulaimani areas (Nasser 1984). Other studies also reported that the mountain forest ecosystems in the northern hemisphere would migrate toward higher elevations under climate change warming scenarios (Bertrand et al. 2011; Braunisch et al. 2014; Walther et al. 2005).

The model also showed a significant contribution of the annual mean temperature (13.5%), slope (15.1%), and aspect (19.9%) to the distribution probability of Q. aegilops in the KRI. Including the annual precipitation, these four predictors collectively contributed 94% in the distribution of the species. The model indicated an optimal annual mean temperature between 13.5 and 16.5 °C, which is the preferred range for the distribution of the species in the KRI. The growth and development of forest plant species are related to various site factors—for example, soil, air temperature, nutrient, light, symbiosis, and disturbances (Desta et al. 2004). The variability of these factors probably depend on the local topography—for example, aspect and slope. Desta et al. (2004) reported that aspect and slope influence the quantity of solar radiation received by the mountain forest during a day cycle. Furthermore, they also affect microclimate of forest plants—for example, humidity, soil moisture, and air temperature (Fekedulegn et al. 2003; Rosenberg et al. 1983). In the KRI, Q. aegilops shows a distribution probability within the optimal range of 10° and 40° aspect (i.e., north and northeast aspects). This result concurs with the study of Desta et al. (2004) in which they showed the north and northeast aspect was more suitable for thriving some mountain tree species—for example Q. prinus and Q. alba. This result does not imply that Q. aegilops would not occur in the southwest and flat surfaces in the KRI.

This study acknowledges that Q. aegilops, despite ongoing degradation, is widely distributed and is the dominant oak species in the KRI. However, climate change and other ongoing human-caused threats (e.g., war, cutting and clearing) are still serious. Therefore, this study suggests the following: (i) introducing oak seed (acorn) into areas with high elevations to test the adaptability of the species; (ii) incorporating climate change adaptation strategic plans into forest management guidelines for conservation efforts—for example, Q. aegilops plantation (assisted migration) at high altitude areas; (iii) and establishment of national parks and protective areas for the oak forests.

Conclusions

Correlation-based modeling of the species available records and environmental predictors provide a useful opportunity to map and predict the current and future distributions of Q. aegilops in the KRI. The output of the modeling (i.e., categorical current and potential habitat suitability maps) can effectively be used to improve conservation actions and plans, not only for the study site, but also for areas with similar climatic conditions—for example, semi-arid regions of the globe where the species is distributed.

The distribution of Q. aegilops was mainly controlled by annual precipitation. Under future climate change scenarios (i.e., RCP2.6 2070 and RCP8.5 2070), the centroid of the distribution would shift toward higher altitude, suggesting its preference for cooler areas with high annual precipitation. Conservation actions should focus on the mountainous areas (e.g., by establishment of national parks and protected areas) of the KRI as climate changes. The mountains hold the future for Q. aegilops in the KRI. Because of its trunk and branch volumes, Q. aegilops forests provide remarkable ecological services for the society. Furthermore, under the two future climate change scenarios, the distribution range of Q. aegilops in the KRI would reduce by 3.6% (1849.7 km2) and 3.2% (1627.1 km2), respectively. By contrast, the species range would expand by 1.5% (777.0 km2) and 1.7% (848.0 km2), respectively. These findings indicate that a significant suitable habitat range of the species will be lost in the KRI due to climate change by 2070. In the KRI, the forest sector, particularly, Q. aegilops forest areas that are vulnerable to climate change were revealed, despite some marginal opportunity for expansion, conservation and management actions should focus on the areas (depicted in Figs. 5 and 6) where the species is most vulnerable. For example, by practicing land allocation and zoning strategies at specific mountain sites where climatic and environmental predictors are in favor of the species.

Availability of data and materials

Applicable on request

Abbreviations

- AR5:

-

Assessment Report 5

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating curve

- BCC-CSM1.1:

-

Beijing Climate Centre - Climate System Modelling 1.1

- CGIAR:

-

Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research

- DEM:

-

Digital elevation model

- GBIF:

-

Global Biodiversity Information Facility

- GLM:

-

Generalized linear models

- GAM:

-

Generalized additive models

- IPCC:

-

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- KRI:

-

Kurdistan Region of Iraq

- MaxEnt:

-

Maximum entropy

- RF:

-

Random forest

- RCP:

-

Representative Concentration Pathway

- SRTM:

-

Shuttle Radar Topography Mission

- SDMs:

-

Species distribution models

- SAGE:

-

Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment

- TSS:

-

True Skill Statistics

References

Abdullah A, Esmail A, Ali O (2019) Mineralogical properties of oak forest soils in Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Iraqi J Agric Sci 50:1501–1511

Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Carvalheiro LG, Polce C, van Loon EE, Raes N, Reemer M, Biesmeijer JC (2013) Fit-for-purpose: species distribution model performance depends on evaluation criteria – Dutch hoverflies as a case study. PLoS One 8:e63708

Aitken SN, Yeaman S, Holliday JA, Wang T, Curtis-McLane S (2008) Adaptation, migration or extirpation: climate change outcomes for tree populations. Evol Appl 1:95–111

Allouche O, Tsoar A, Kadmon R (2006) Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J Appl Ecol 43:1223–1232

Alnasrawi A (2001) Iraq: economic sanctions and consequences, 1990–2000. Third World Q 22:205–218

Ardi M, Rahmani F, Siami A (2012) Genetic variation among Iranian oaks (Quercus spp.) using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers. Afr J Biotechnol 11:10291–10296

Balci Y, Halmschlager E (2003) Phytophthora species in oak ecosystems in Turkey and their association with declining oak trees. Plant Pathol 52:694–702

Bertrand R et al (2011) Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479:517–520

Boakes EH, McGowan PJK, Fuller RA, Ding CQ, Clark NE, O’Connor K, Mace GM (2010) Distorted views of biodiversity: spatial and temporal bias in species occurrence data. PLoS Biol 8:e1000385

Bor N, Guest E (1968) Flora of Iraq, vol 9. Ministry of Agriculture, Baghdad

Boria RA, Olson LE, Goodman SM, Anderson RP (2014) Spatial filtering to reduce sampling bias can improve the performance of ecological niche models. Ecol Model 275:73–77

Braunisch V, Coppes J, Arlettaz R, Suchant R, Zellweger F, Bollmann K (2014) Temperate mountain forest biodiversity under climate change: compensating negative effects by increasing structural complexity. PLoS One 9:e97718

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45:5–32

Brown JL (2014) SDM toolbox: a python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Methods Ecol Evol 5:694–700

Brown JL, Bennett JR, French CM (2017) SDMtoolbox 2.0: the next generation Python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. PeerJ 5:e4095

Chapman G (1948) Forestry in Iraq. Unasylva 2:251–253

Chapman G (1950) Notes on forestry in Iraq. Empire Forestry Rev:132–135

Desta F, Colbert J, Rentch JS, Gottschalk KW (2004) Aspect induced differences in vegetation, soil, and microclimatic characteristics of an Appalachian watershed. Castanea 69:92–108

Di Filippo A, Alessandrini A, Biondi F, Blasi S, Portoghesi L, Piovesan G (2010) Climate change and oak growth decline: Dendroecology and stand productivity of a Turkey oak (Quercus cerris L.) old stored coppice in Central Italy. Ann For Sci 67:706

Dormann CF et al (2013) Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 36:27–46

Duan R-Y, Kong X-Q, Huang M-Y, Fan W-Y, Wang Z-G (2014) The predictive performance and stability of six species distribution models. PLoS One 9:e112764

Dudík M, Phillips SJ, Schapire RE (2007) Maximum entropy density estimation with generalized regularization and an application to species distribution modeling. J Mach Learn Res 8:1217–1260

Ebrahimi A, Farashi A, Rashki A (2017) Habitat suitability of Persian leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Iran in future. Environ Earth Sci 76:697

Elith J, Kearney M, Phillips S (2010) The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol Evol 1:330–342

Elith J, Leathwick JR (2009) Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:677–697

Elith J et al (2006) Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129–151

El-Moslimany AP (1986) Ecology and late-Quaternary history of the Kurdo-Zagrosian oak forest near Lake Zeribar, western Iran. Vegetatio 68:55–63

Fekedulegn D, Hicks RR Jr, Colbert J (2003) Influence of topographic aspect, precipitation and drought on radial growth of four major tree species in an Appalachian watershed. For Ecol Manag 177:409–425

Fielding AH, Bell JF (1997) A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environ Conserv 24:38–49

Gaertig T, Schack-Kirchner H, Hildebrand EE, Wilpert KV (2002) The impact of soil aeration on oak decline in southwestern Germany. For Ecol Manag 159:15–25

Ghafour NH, Aziz HA, Almolla RAM (2010) Determination of some chemical constitutes of oak plants (Quercus spp.) in the mountain oak forest of Sulaimani Governorate. J Zankoy Sulaimani 13:129–142

Ghahramany L, Ghazanfari H, Fatehi P, Valipour A (2018) Structure of pollarded oak forest in relation to aspect in Northern Zagros, Iran. Agrofor Syst 92:1567–1577

Graham MH (2003) Confronting multicollinearity in ecological multiple regression. Ecology 84:2809–2815

Guest E, Al-Rawi A (1966) Flora of Iraq. Vol. 1: Introduction. Ministry of Agriculture. University Press, Glasgow

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1982) The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36

Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ (1990) Generalized additive models vol 43. CRC Press

Hatt RT (1959) The mammals of Iraq

Hernández-Lambraño RE, de la Cruz DR, Sánchez-Agudo JÁ (2019) Spatial oak decline models to inform conservation planning in the Central-Western Iberian Peninsula. For Ecol Manag 441:115–126

Heydari M, Rostamy A, Najafi F, Dey D (2017) Effect of fire severity on physical and biochemical soil properties in Zagros oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) forests in Iran. J For Res 28:95–104

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978

Hirzel AH, Hausser J, Chessel D, Perrin N (2002) Ecological-niche factor analysis: how to compute habitat-suitability maps without absence data? Ecology 83:2027–2036

Hu X-G, Jin Y, Wang X-R, Mao J-F, Li Y (2015) Predicting impacts of future climate change on the distribution of the widespread conifer Platycladus orientalis. PLoS One 10:e0132326

Jewitt D, Erasmus BF, Goodman PS, O'Connor TG, Hargrove WW, Maddalena DM, Witkowski ET (2015) Climate-induced change of environmentally defined floristic domains: A conservation based vulnerability framework. Appl Geogr 63:33–42

Jiménez-Valverde A, Lobo JM (2007) Threshold criteria for conversion of probability of species presence to either–or presence–absence. Acta Oecol 31:361–369

Junttila O, Nilsen J (1993) Growth and development of northern forest trees as affected by temperature and light. In: Alden J, Mastrantonio JL, Ødum S (eds), Forest development in cold climates. Plenum Press, New York, pp 43–57

Körner C et al (2016) Where, why and how? Explaining the low-temperature range limits of temperate tree species. J Ecol 104:1076–1088

Kramer-Schadt S et al (2013) The importance of correcting for sampling bias in MaxEnt species distribution models. Divers Distrib 19:1366–1379

Liu C, White M, Newell G (2013) Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J Biogeogr 40:778–789

Malinowski JC (2002) Iraq: A Geography

Maya-García R, Torres-Miranda CA, Cuevas-Reyes P, Oyama K (2020) Morphological differentiation among populations of Quercus elliptica Neé (Fagaceae) along an environmental gradient in Mexico and Central America. Botanical Sci 98:50–65

McCullagh P (1984) Generalized linear models. Eur J Oper Res 16:285–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(84)90282-0

Merow C, Smith MJ, Silander JA Jr (2013) A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species’ distributions: what it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography 36:1058–1069

Morales NS, Fernández IC, Baca-González V (2017) MaxEnt’s parameter configuration and small samples: are we paying attention to recommendations? A systematic review. PeerJ 5:e3093

Mosa WL (2016) Forest Cover Change and Migration in Iraqi Kurdistan: A Case Study from Zawita Sub-district. Michigan State University. Forestry.

Nasser M (1984) Forests and forestry in Iraq: prospects and limitations. Commonwealth Forestry Rev:299–304

Nixon K (2006) Global and neotropical distribution and diversity of oak (genus Quercus) and oak forests. In: Ecology and conservation of neotropical montane oak forests. Springer, pp 3–13

Obeyed M, Akrawee Z, Mustafa Y (2020) Estimating aboveground biomass and carbon sequestration for natural stands of Quercus aegilops in Duhok province, Iraqi. J Agric Sci 51. https://doi.org/10.36103/ijas.v51i1.936

Panahi P, Jamzad Z, Pourmajidian M, Fallah A, Pourhashemi M (2012) Foliar epidermis morphology in Quercus (subgenus Quercus, section Quercus) in Iran. Acta Botanica Croatica 71:95–113

Pearson RG, Raxworthy CJ, Nakamura M, Peterson AT (2007) Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: a test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J Biogeogr 34:102–117

Phillips SJ (2005) A brief tutorial on Maxent. AT&T Res 190:231–259

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Dudík M, Schapire RE, Blair ME (2017) Opening the black box: An open-source release of Maxent. Ecography 40:887–893

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Model 190:231–259

Phillips SJ, Dudík M (2008) Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31:161–175

Pourreza M, Hosseini SM, Sinegani AAS, Matinizadeh M, Dick WA (2014) Soil microbial activity in response to fire severity in Zagros oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) forests, Iran, after one year. Geoderma 213:95–102

Radosavljevic A, Anderson RP (2014) Making better Maxent models of species distributions: complexity, overfitting and evaluation. J Biogeogr 41:629–643

Rahimi I, Azeez SN, Ahmed IH (2020) Mapping forest-fire potentiality using remote sensing and GIS, case study: Kurdistan Region-Iraq. In: Environmental Remote Sensing and GIS in Iraq. Springer, pp 499–513

Ramírez-Preciado RP, Gasca-Pineda J, Arteaga MC (2019) Effects of global warming on the potential distribution ranges of six Quercus species (Fagaceae). Flora 251:32–38

Rashid RMS, Sabir DA, Hawramee OK (2014) Effect of sweet acorn flour of common oak (Quercus aegilops L.) on locally Iraqi pastry (kulicha) products. J Zankoy Sulaimani 16:244–249

Riahi K et al (2011) RCP 8.5—A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim Change 109:33–57

Rosenberg NJ, Blad BL, Verma SB (1983) Microclimate: the biological environment. Wiley, New York

Salehi A, Farzin M, Alizadeh S (2019) Determination of effective factors on natural regeneration of Persian Oak in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Sothern Zagros, Iran. Arid Ecosyst 9:193–201

Salim M, Ararat K, Abdulrahman OF (2010) A provisional checklist of the Birds of Iraq. RF Porter, M Salim, K Ararat and O Fadhel on behalf of Nature. Iraq Marsh Bull 5:56–95

Shahbaz S (2010) Trees and shrubs: A field guide to the trees and shrubs of Kurdistan region of Iraq. J Univ Duhok

Shahbaz SE, Abdulrahman SS, Abdulrahman HA (2015) Use of leaf anatomy for identification of Quercus L. species native to Kurdistan-Iraq. Science J Univ Zakho 3:222–232

Sissakian V, Jabbar MA, Al-Ansari N, Knutsson S (2015) Development of Gulley Ali Beg Gorge in Rawandooz Area, Northern Iraq. Engineering 7:16–30

Soberon J, Peterson AT (2005) Interpretation of models of fundamental ecological niches and species’ distributional areas. Biodiversity Informatics 2:1–10

Song Y-G, Petitpierre B, Deng M, Wu J-P, Kozlowski G (2019) Predicting climate change impacts on the threatened Quercus arbutifolia in montane cloud forests in southern China and Vietnam: Conservation implications. For Ecol Manag 444:269–279

Syfert MM, Smith MJ, Coomes DA (2013) The effects of sampling bias and model complexity on the predictive performance of MaxEnt species distribution models. PLoS One 8:e55158

Task GSD (2000) Global soil data products CD-ROM (IGBP-DIS), CD-ROM International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, Data and Information System, Potsdam, Germany. Available from Oak Ridge National Laboratory Distributed Active Archive Center, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA

Townsend Peterson A, Papeş M, Eaton M (2007) Transferability and model evaluation in ecological niche modeling: a comparison of GARP and Maxent. Ecography 30:550–560

Trumbore S, Brando P, Hartmann H (2015) Forest health and global change. Science 349:814–818

Tsoar A, Allouche O, Steinitz O, Rotem D, Kadmon R (2007) A comparative evaluation of presence-only methods for modelling species distribution. Divers Distrib 13:397–405

Urban MC (2015) Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science 348:571–573

Van den Bergh M, Kappelle M (2006) Small terrestrial rodents in disturbed and old-growth montane oak forest in Costa Rica. In: Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical Montane Oak Forests. Springer, pp 337–345

Van Vuuren DP et al (2011) RCP2.6: exploring the possibility to keep global mean temperature increase below 2 oC. Clim Change 109:95–116

Walther GR, Beißner S, Burga CA (2005) Trends in the upward shift of alpine plants. J Veg Sci 16:541–548

Wang JR, Hawkins C, Letchford T (1998) Photosynthesis, water and nitrogen use efficiencies of four paper birch (Betula papyrifera) populations grown under different soil moisture and nutrient regimes. For Ecol Manag 112:233–244

Willmott C, Matsuura K (2001) Terrestrial Water Budget Data Archive: Monthly Time Series (1950–1999) Version 1.02

Wisz MS, Hijmans R, Li J, Peterson AT, Graham C, Guisan A, Group NPSDW (2008) Effects of sample size on the performance of species distribution models. Divers Distrib 14:763–773

Woodward FI, Williams B (1987) Climate and plant distribution at global and local scales. Vegetatio 69:189–197

Xu J, Song Y-G, Deng M, Jiang X-L, Zheng S-S, Li Y (2020) Seed germination schedule and environmental context shaped the population genetic structure of subtropical evergreen oaks on the Yun-Gui Plateau, Southwest China. Heredity 124:499–513

Yi Y-J, Zhou Y, Cai Y-P, Yang W, Li Z-W, Zhao X (2018) The influence of climate change on an endangered riparian plant species: The root of riparian Homonoia. Ecol Indic 92:40–50

Younis AJ, Hassan MK (2019) Assessing volume of Quercus aegilops L. trees in Duhok Governorate, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. J Duhok Univ 22:265–276

Zhang K, Yao L, Meng J, Tao J (2018) Maxent modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution of two peony species under climate change. Sci Total Environ 634:1326–1334

Zohary M (1973) Geobotanical foundations of the Middle East. Gustav Fisher Verlag, Amsterdam

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Sara Kamal Othman for reviewing and proofreading the manuscript. The support and assistance of the University of Sulaimani, in particular, Department of Biology is highly appreciated.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khwarahm, N.R. Mapping current and potential future distributions of the oak tree (Quercus aegilops) in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Ecol Process 9, 56 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00259-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00259-0