Abstract

In the Northeastern U.S., drought is expected to increase in frequency over the next century, and therefore, the responses of trees to drought are important to understand. There is recent debate about whether land-use change or moisture availability is the primary driver of changes in forest species composition in this region. Some argue that fire suppression from the early twentieth century to present has resulted in an increase in shade-tolerant and pyrophobic tree species that are drought intolerant, while others suggest precipitation variability as a major driver of species composition. From this debate, an emerging hypothesis is that mesophication and increases in the abundance of mesophytic genera (e.g., Acer, Betula, and Fagus) resulted in forests that are more vulnerable to drought. This review examines the published literature and factors that contribute to drought vulnerability of Northeastern U.S. forests. We assessed two key concepts related to drought vulnerability, including drought tolerance (ability to survive drought) and sensitivity (short-term responses to drought), with a focus on Northeastern U.S. species. We assessed drought-tolerance classifications for species, which revealed both consistencies and inconsistencies, as well as contradictions when compared to actual observations, such as higher mortality for drought-tolerant species. Related to drought sensitivity, recent work has focused on isohydric/anisohydric regulation of leaf water potential. However, based on the review of the literature, we conclude that drought sensitivity should be viewed in terms of multiple variables, including leaf abscission, stomatal sensitivity, turgor pressure, and dynamics of non-structural carbohydrates. Genera considered drought sensitive (e.g., Acer, Betula, and Liriodendron) may actually be less prone to drought-induced mortality and dieback than previously considered because stomatal regulation and leaf abscission in these species are effective at preventing water potential from reaching critical thresholds during extreme drought. Independent of drought-tolerance classification, trees are prone to dieback and mortality when additional stressors are involved such as insect defoliation, calcium and magnesium deficiency, nitrogen saturation, and freeze-thaw events. Overall, our literature review shows that multiple traits associated with drought sensitivity and tolerance are important as species may rely on different mechanisms to prevent hydraulic failure and depleted carbon reserves that may lead to mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Introduction

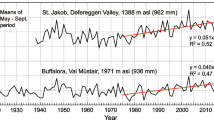

Northeastern U.S. forests play an important role in storing carbon (Woodbury et al. 2007) and regulating energy, biogeochemical, and hydrological climate feedbacks (Bonan 2008). In addition, temperate forest ecosystems in this region provide many economic, ecological, and recreational benefits (O’Brien 2006; Benjamin et al. 2009). Given the high societal and ecological value of these forests, it is critical that we improve our ability to predict forest responses to future climate change. While typically considered to be light-, temperature-, and nutrient-limited (Boisvenue and Running 2006; Rennenberg and Dannenmann 2015), the historical role and potential future importance of drought in driving forest dynamics in this region is being increasingly recognized. Throughout the twentieth century, both temperature and precipitation have increased (Hayhoe et al. 2007; Wake et al. 2014), with the late twentieth century being one of the wettest periods within the last 500 years (Pederson et al. 2015). During this period, drought events from 1961 to 1990 typically lasted between one to 3 months and rarely exceeded 3 months (Hayhoe et al. 2007). The exception was the multi-year drought in the 1960s (1962–1965; Namias 1967, Namias 1966), which was likely the most severe drought in the last 500 years (Pederson et al. 2013). Future climate projections under high CO2 emission scenarios indicate that more frequent droughts lasting 1–2 months throughout most of the Northeastern U.S., as well as 3–6 months in localized areas in the Northeastern U.S., will be punctuated among larger rain events (Hayhoe et al. 2007; Wake et al. 2014). The recent summer 2016 drought where large areas across the Northeastern U.S. received 25–75% of normal precipitation (July 1–September 30; http://www.drought.gov) may be a harbinger of such future trends.

There is growing evidence that drought influences changes in species composition at much larger time-scales (Booth et al. 2012) and reduces canopy photosynthesis and tree growth at shorter time-scales (Urbanski et al. 2007; Martin-Benito and Pederson 2015). Responses occurring at different time-scales relate to differences in species’ drought tolerance, which is the ability to survive drought events, and drought sensitivity, which we define as short- to medium-term physiological response. Recent declines in mature northern hardwood forest tree species such as Acer saccharum, Betula papyrifera, and Betula allegheniensis (Auclair et al. 1996) and widespread dieback of A. saccharum (Jones and Hendershot 1989; Payette et al. 1996; Horsley et al. 2002; Roy et al. 2004; Roy et al. 2006) and Picea rubens (Siccama et al. 1982; Johnson 1983) have been, in part, attributed to drought along with other factors such as freeze-thaw events, insect defoliation, acid rain, nutrient availability, and forest succession. Across forests of the Northeastern U.S., tree species can vary widely in leaf photosynthetic responses to declining soil moisture availability, although species growing in mesic and wet-mesic sites tend to be more sensitive to drought than xeric sites (Kubiske and Abrams 1994). Canopy photosynthesis can be inhibited during seasonal periods of low soil moisture, reducing the overall carbon sink-strength of forests (Urbanski et al. 2007). Using dendrochronology, a number of studies have also reported reductions in tree radial growth during years of low precipitation (Cook and Jacoby 1977; Conkey 1979; Kolb and Mccormick 1993; Abrams et al. 2000; Pederson et al. 2013; Martin-Benito and Pederson 2015).

The overall trend in species composition in the region has been one of “mesophication” (Nowacki and Abrams 2008), the gradual replacement of shade intolerant, fire-adapted species (Pinus spp., Quercus spp., Carya spp.) with shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive species (Acer spp., Betula spp., Fagus grandifolia). While some argue that human influence and land use change have played the strongest role (Nowacki and Abrams 2015), others suggest that increasing precipitation over the last century is a primary driver of this tree species shift (Pederson et al. 2015). The prevailing argument for the former is that as Northeastern U.S. forests recovered from widespread forest clearing throughout the eighteenth and ninetieth centuries (Foster et al. 1998, Foster et al. 2010), fire suppression policies starting in the 1920s to present day led to a “mesophication” of central hardwoods (i.e., oak-pine forests) that involved a compositional shift towards more pyrophobic species (Acer spp., F. grandifolia, Betula spp., Prunus serotina, Liriodendron tulipifera, Tsuga canadensis) and substantial losses of pyrophilic species (Quercus spp., Pinus spp., Castanea spp.). However, mesophication trends during the last century have also been attributed to recent increases in precipitation based on evidence of soil moisture limitations on tree establishment, growth, and survival, as well as consistent changes among historic climate and species composition (Pederson et al. 2015). The period of 1930–2005 was one of the wettest periods on record throughout most of the eastern USA (Pederson et al. 2015), which may have contributed to the recent mesophication. Ultimately, interactions between climate and land use change have likely contributed to shifts in species composition and point to a common hypothesis: the present mesophytic species will be especially vulnerable to future severe droughts, and consequently, Northeastern U.S. Forests may experience dramatic shifts in species composition with increasing drought frequency and intensity (Abrams and Nowacki 2016). However, evidence in support of this hypothesis is largely lacking, given the historical rarity of past droughts in the region, combined with a lack of targeted research on forest response to drought—a topic not traditionally considered relevant until only recently.

Accurate understanding of species’ and forest responses to drought is fundamental to making predictions of future trajectories and designing effective management approaches, as has been shown for a range of ecosystems in moisture-limited climates (Skov et al. 2004; Simonin et al. 2007; McDowell et al. 2008; Adams et al. 2012; Anderegg et al. 2015). However, similar in-depth characterization of drought-ecosystem interactions has lagged in Northeastern U.S. forests, with previous approaches largely restricted to broad classification of drought tolerance based on species’ traits or growing conditions. Nevertheless, recent studies have started to examine physiological mechanisms associated with drought-sensitivity in Northeastern U.S. species (Johnson et al. 2011; Roman et al. 2015; Yi et al. 2017), thereby broadening our understanding of forest vulnerability to drought. In this review, we find that multiple ways of characterizing drought response (e.g., tolerance and sensitivity) are important in characterizing different temporal and spatial scales. Here, we refer to drought tolerance as the ability of a particular species to survive a long-term drought event with minimal damage to branches, whereas sensitivity refers to short-term (e.g., one growing season or less), physiological responses to drought. The term vulnerability is also used in this review, which refers to longer term risk of mortality or dieback associated with drought. In this paper, we first review past approaches to classifying drought tolerance and drought sensitivity of Northeastern U.S. species, with an eye towards understanding their ability to capture consistent patterns as reflected in agreement (or inconsistency) between different studies, and between predictions and observations. Second, we review the current knowledge of linkages between drought tolerance and sensitivity to further develop our understanding of vulnerability to drought-induced mortality necessary for refining broader classifications of species drought tolerance.

Classification of drought tolerance of Northeastern U.S. species

Because drought-induced mortality events have been relatively infrequent in Northeastern U.S. forests (Allen et al. 2010), criteria including site or growing conditions, physiological responses, and plant traits have typically been used in classifying species’ drought tolerance. Otherwise, drought classification would be solely based on mortality and severity of dieback. Classification of drought tolerance often relies heavily on the geographic range of species distribution (especially in relation to soil moisture availability) as an indicator of a particular species’ capacity to survive moisture stress. These classification systems are developed using published sources of species’ range and environmental conditions to infer drought tolerance, including the Silvics of North America, USDA Plants Database, USDA Tree Atlas, and US Forest Service Fire Effects Information System (Niinemets and Valladares 2006; Matthews et al. 2011; Gustafson and Sturtevant 2013; Peters et al. 2015). It is worth noting that Gustafson and Sturtevant (2013) and Niinemets and Valladares (2006) also incorporated US Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) mortality data and published results of crown dieback (> 50% branch dieback) for a few species, respectively, to aid in species drought classification.

With respect to Northeastern U.S. tree species, there are both consistencies and discrepancies in how species are classified in terms of drought tolerance. Several species among studies (Niinemets and Valladares 2006; Gustafson and Sturtevant 2013; Peters et al. 2015) are consistently classified as drought-tolerant (e.g., Quercus spp., P. serotina, and Pinus banksiana) and drought intolerant (e.g., Betula spp., Populus spp., T. canadensis, and Abies balsamea) (Table 1). The major inconsistencies in drought tolerance classifications occur for Pinus strobus, Acer spp., Fraxinus americana, Tilia americana, and Picea rubens among the three studies (Table 1). Also, drought-tolerant species (as classified by Niinemets and Valladares 2006) actually displayed a higher sensitivity (i.e., greater reductions in stem growth) during drought as compared to drought-intolerant species (Phillips et al. 2016). Likewise, species consistently classified as drought tolerant (e.g. Quercus spp.) experienced higher mortality following an extreme drought year in the Midwestern USA as compared with presumably more drought intolerant species, Acer saccharum and Fraxinus americana (Gu et al. 2015). The inconsistency in classification across studies presents a conundrum that plagues drought research: uncertainty in how we define tolerance and what criteria should be used to classify species in a reliable and meaningful way.

The advantage of using established classification systems is that they provide general information for nearly all tree species of the USA. A limitation of this approach is its reliance on fundamental (and often untested) assumptions about the relationship between growing conditions and vulnerability to dieback or mortality during drought (Niinemets and Valladares 2006; Gustafson and Sturtevant 2013; Peters et al. 2015). The USDA Plants Database categorizes species’ drought tolerance (low, medium, high) based on field observations but not necessarily on measurements and experiments (USDA, NRCS 2017). The USDA Plants Database also does not indicate what the field observations are based on. The Silvics of North America provides general information about site and soil conditions (e.g., precipitation and soil texture) where species grow. However, this approach to drought tolerance classification lacks a mechanistic understanding of what determines species’ tolerance, as geographic distributions may be confounded by numerous other factors (e.g., successional change, land use, competitive interactions, and biotic agents). Another potential issue with this approach is that certain species like Tsuga canadensis tend to grow at moist sites such as ravines, swamp edges, and north-facing slopes (Burns and Honkala 1990), which can lead to the assumption that this species is drought-intolerant. However, it is unclear whether T. canadensis is less tolerant of drought than other co-occurring species at the same sites. While studies have made important progress in understanding tree mortality and drought (Gustafson and Sturtevant 2013), habitat suitability of Northeastern U.S. species (Matthews et al. 2011), and linkages between shade and drought-tolerance (Niinemets and Valladares 2006), simple drought classifications may not account for specific mechanisms or functional traits that maintain growth or survival during drought.

Nowacki and Abrams (2008) proposed that the process of mesophication over the last century in Northeastern U.S. forests involves establishment and overstory dominance of shade-tolerant species that generate dense shading, moist and cool microclimates at and near the soil surface, and a relatively inflammable fuel bed. Subsequently, fire is less prone to occur in these mesophytic forest-types. If recent mesophication due to fire suppression has in fact led to greater vulnerability of Northeastern U.S. forests to drought, then this hypothesis would imply strong linkages among drought tolerance, fire tolerance, and shade intolerance across species (Abrams and Nowacki 2016). In tree species across North America, Europe, and East Asia, there are inverse, albeit weak, correlations (R 2 of 0.02 to 0.16) between shade and drought tolerance (Niinemets and Valladares 2006). Shade-tolerant species in the Northeastern U.S. have experienced greater reductions in photosynthesis (e.g., stomatal and non-stomatal limitations) in response to drought (Kubiske et al. 1996), but declines in photosynthesis is a metric for drought-sensitivity and not necessarily associated with lower drought tolerance because declines in photosynthesis do not imply greater risk of drought-induced mortality. In other forest biomes such as tropical dry and moist tropical forests, there is little evidence for a trade-off between drought and shade tolerance (Markesteijn and Poorter 2009). In fact, drought tolerance was more closely associated with greater biomass allocation to roots, whereas shade tolerance was more closely associated with low-specific leaf area and slower growth rates in tropical dry and moist tropical forests (Markesteijn and Poorter 2009). Less is known regarding the link between drought tolerance and pyrophillic species in temperate forests. Pyrophilic tree genera of the Northeastern U.S. generally include Carya, Castanea, Pinus, Populus, and Quercus (Abrams and Nowacki 2016). Quercus and Castanea spp. are considered drought-tolerant species, Populus spp. are mostly considered intolerant, and Pinus spp. are considered both tolerant and intolerant (Table 1).

Classification of drought sensitivity of Northeastern U.S. species

Plant species possess specific adaptive strategies that allow them to either avoid or permit dehydration or reductions in plant water potential in response to drought (Pallardy 2008). Species that avoid dehydration are generally considered more sensitive to drought. There are many adaptations to drought, including specific traits or responses that regulate plant water potential because water potential and components of leaf water potential, turgor pressure, and osmotic potential, are intricately linked with important physiological processes including survival, growth, gas exchange, leaf anatomy, and many biochemical processes during drought (Jones 1992; Pallardy 2008; Lambers et al. 2008).

A commonly observed adaptation to drought for Northeastern U.S. tree species is isohydric regulation of leaf water potential through stomatal control. Northern hardwood (A. saccharum, B. alleghaniensis, and F. grandifolia) and other species of the Northeastern U.S. display large declines in stomatal conductance with little change in leaf water potential during drought (Federer and Gee 1976; Kubiske and Abrams 1994). Species are also capable of permitting and tolerating declines in leaf water potential (e.g., anisohydry); however, this type of tolerance strategy appears to be less common. A number of studies have highlighted the anisohydric behavior of Quercus species compared with co-occurring species such as Acer rubrum, A. saccharum, B. papyrifera, L. tulipifera, Populus grandidentata, and Sassafras albidum (Federer 1980; Bovard et al. 2005: Yi et al. 2017). Adaptations that enable Northeastern U.S. tree species to tolerate lower water potentials generally include adjustments in osmotic potential (Parker et al. 1982; Kubiske and Abrams 1994) or cell wall thickness (Kubiske and Abrams 1994) to sustain or minimize reductions in cell turgor pressure. Within the Northeastern U.S. there is some evidence for osmotic adjustments, particularly for species growing in more xeric sites (Kubiske and Abrams 1994). However, across a larger spatial scale, species growing in relatively wet climates, such as the Northeastern U.S., appear to be less dependent on osmotic adjustments during drought as compared with drier regions of the U.S. (Abrams 1990; Kubiske and Abrams 1992).

Since the isohydric-anisohydric framework represents an approach for classifying species drought responses and serves as an indicator of stomatal sensitivity, its definition may affect our conclusions regarding species sensitivity to drought (Table 2). Historically, species have been divided into two broad categories: isohydric or anisohydric. Isohydric species regulated water potential via stomatal closure (or reduced stomatal aperture) above a critical threshold while anisohydric species allow water potential to decline as the soil dries (Loewenstein and Pallardy 1998; Tardieu and Simonneau 1998), although the critical threshold was often ambiguous. More recently, studies have worked towards a quantitative description of the isohydric-anisohydric framework that required deriving parameters from empirical relationships of leaf water potential, stomatal conductance, and/or hydraulic conductance (Table 2, Martinez-Vilalta et al. 2014; Klein 2014; Roman et al. 2015; Skelton et al. 2015; Garcia-Forner et al. 2016; Meinzer et al. 2016). An important finding of many of these studies is that species exhibit a continuum of isohydric-anisohydric behavior rather than a dichotomy.

Despite common drought-response behavior within species, there are some inconsistencies in classification among studies (Table 2). Quercus species are frequently classified as displaying anisohydric behavior (Loewenstein and Pallardy 1998; Roman et al. 2015) with an exception (Martinez-Vilalta et al. 2014). This may be due, in part, to the fact that Martinez-Vilalta et al. (2014) classified species across a number of biomes (e.g., desert, temperate, and tropical), whereas Loewenstein and Pallardy (1998) and Roman et al. (2015) compared species at one site. Thus, spatial scale likely influences where species fall along the isohydric-anisohydric spectrum, with larger scales leading to a greater range between end points and, consequently, changes in species’ relative position across the spectrum. Another common species of the Northeastern U.S., A. saccharum, was classified as isohydric (Roman et al. 2015), anisohydric (Loewenstein and Pallardy 1998), or intermediate (Klein 2014). In this case, the spatial scales were similar among two studies that reached different conclusions (Loewenstein and Pallardy 1998; Roman et al. 2015). A notable difference among these studies was that Loewenstein and Pallardy (1998) measured Ψ md values at − 3 MPa and greater declines in stomatal conductance, while Roman et al. (2015) measured Ψ md values in the range of − 0.5 to − 1.0 MPa and smaller declines in stomatal conductance during the most severe portion of a drought. Yet, measurements by Roman et al. (2015) occurred during a more severe drought (June–July precipitation < 10% of mean) than the drought (May–September precipitation 53% of mean) in Loewenstein and Pallardy (1998). Consequently, both the range of the response surface and the severity of the drought can also affect evaluation of species’ anisohydric-isohydric behavior.

Greenhouse experiments that grow seedlings from seeds collected from different habitats show that adaptation to local site conditions can influence how species respond to drought. Site conditions may be a critical factor contributing to the distinct differences in leaf water potential and stomatal responses to drought within species. For example, dry-site genotypes of Cercis canadensis (Abrams 1988), Fraxinus americana (Abrams et al. 1990), and Prunus serotina (Abrams et al. 1992) maintained greater stomatal conductance during drought despite having lower or similar leaf water potential as compared with genotypes from wetter sites. In addition to using seed sources from the Northeastern U.S., these studies also used seed sources that extended outside of the Northeastern U.S. including states like South Dakota, Nebraska (Abrams et al. 1990), Wisconsin (Abrams et al. 1992), and Kansas (Abrams 1988). Nevertheless, studies that used seed sources primarily within the Northeastern U.S. observed greater declines in stomatal conductance and photosynthesis during drought for wet-site genotypes of Acer rubrum (Bauerle et al. 2003) and Quercus rubra (Kubiske and Abrams 1992) compared to dry-site genotypes. Both studies also found that non-stomatal limitations to photosynthesis were greater in wet-site genotypes. Genotypes from drier sites also consistently had more xeromorphic leaves, smaller leaves with greater leaf mass per area and leaf thickness, despite identical environmental conditions during leaf development (Abrams 1988a; Abrams et al. 1990; Abrams et al. 1992; Kubiske and Abrams 1992). Although, both genotypic and phenotypic variation can also influence how temperate deciduous species respond to drought (Abrams 1994). For many temperate deciduous species, phenotypic variation in response to light availability strongly controls leaf and stomatal structural traits associated with drought sensitivity and can interact with genotypic variation associated with adaptation to wet or dry sites (Abrams 1994). For example, genotypic differences between dry- and wet-site seed sources were more evident in Prunus serotina overstory trees exposed to greater light conditions as compared with shade trees (Abrams et al. 1992). Dry-site genotypes consistently had smaller leaf area and guard cell length, as well as greater leaf thickness and leaf mass per area for sun leaves; however, there were no differences in these parameters between dry-site and wet-site genotypes for shade leaves. This has important implications for tree response to drought and suggests that stage of development and light conditions, in addition to its topographic location across the landscape, can influence drought sensitivity.

Based on the trajectory of recent research (Table 2), characterizing species’ responses to drought using the isohydric-anisohydric framework for mature trees will require intensive measurements particularly during periods of water stress. Accomplishing this for species in the Northeastern U.S. may be especially difficult, given the rarity of drought occurrence and high diversity of species in this region. A few possible solutions to this problem may include the use of experiments and targeted monitoring, as well as other measurements to determine isohydric-anisohydric behavior. Experimental work that diverts precipitation from forested plots may be one approach to identifying species sensitivity to drought while progressing trees towards dieback and mortality, which will be an important first step in understanding mechanisms associated with drought tolerance of tree species (Mencuccini et al. 2015). This approach has been implemented in a number of forested ecosystems including temperate deciduous (Tschaplinski et al. 1998; Wullschleger et al. 1998), Eucalyptus grandis (Battie-Laclau et al. 2014), and tropical forests (Fisher et al. 2007) in order to understand physiological responses to drought. Sap-flow measurements may circumvent logistical issues with intensive gas exchange measurements in tall, mature trees, as well as improve the timing of targeted physiological measurements. Yi et al. (2017) show that measurement of sap-flow is a reliable method for identifying species water-use strategies and stomatal sensitivity (isohydric vs. anisohydric). For example, both canopy conductance (g c ) as estimated from sap-flow measurements and stomatal conductance (g s ) as estimated from leaf gas exchange measurements displayed similar responses to drought across all species examined (Yi et al. 2017). Isohydric species (A. saccharum, L. tulipifera) experienced greater declines in both g c and g s than anisohydric species (Quercus alba, Q. rubra) (Roman et al. 2015; Yi et al. 2017).

Stomatal regulation of leaf water potential is just one mechanism by which plants can avoid water stress. In fact, species can avoid declines in leaf water potential through leaf abscission (Hoffmann et al. 2011) and adjustments in stomatal morphology (Abrams et al. 1994). Leaf abscission is an important strategy in temperate deciduous forests in minimizing the risk of hydraulic failure (Hoffmann et al. 2011) and aiding in recovery of photosynthesis following a drought (Gu et al. 2007) and has been reported for a number of species in the Northeastern U.S. including A. rubrum, A. saccharum, B. papyrifera, Juglans nigra, L. tulipifera, Liquidambar styraciflua, and Nyssa sylvatica (Federer 1980; Roberts et al. 1980; Parker and Pallardy 1985; Pallardy 1993; Tyree et al. 1993; Gu et al. 2007; Hoffmann et al. 2011). Adjustments in stomatal morphology were found by Abrams et al. (1994) across 17 temperate deciduous species of the Northeastern U.S., where species having a smaller guard cell length maintained lower stomatal conductance and higher leaf water potential during drought. Smaller guard cell length likely increases resistance of water vapor through the stomata. Species can also postpone declines in leaf water potential during drought through stem water storage and greater rooting depth (Abrams 1990). Postponing declines in leaf water potential through stem water storage seems to be more relevant for species growing in tropical dry forests that regularly experience a dry period, as compared with temperate deciduous species (Borchert and Pockman 2005). Postponing declines in leaf water potential through greater rooting depth is more common for Quercus species (Abrams 1990; Pallardy 1993).

While past research on drought responses and sensitivity of Northeastern U.S. tree species primarily emphasized mechanisms associated with regulation of leaf water potential, responses that involve shifts in carbon allocation or decreases in non-structural carbohydrates (NSC; e.g., sugars and starches that support metabolic function and growth) are also indicative of drought sensitivity. In fact, models like PnET-II strongly rely on carbon allocation in modeling forest water yield and productivity in response to drought for Northeastern U.S. forests (Aber et al. 1995; Ollinger et al. 1997). For example, PnET-II estimates components of stand water balance (Aber and Federer 1992), which determines the degree of water stress and subsequent declines in net photosynthesis. PnET-II also estimates the total plant mobile carbon pool, which is dependent on net photosynthesis. The total plant mobile carbon pool is first allocated to leaf biomass, and the remaining carbon is allocated to wood production. Thus, it is assumed that carbon allocation is a passive process where mobile carbon pools simultaneously decrease with photosynthesis during drought, and consequently, leaf and wood growth is also reduced. However, there is also evidence that mobile carbon pools may be actively regulated and compete with wood growth during periods of drought or low-carbon supply (Sala et al. 2012). This hypothesis is supported in European temperate deciduous species, Quercus petraea and Fagus sylvatica, where stem growth was reduced during a summer drought, but non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) concentration did not change (Barbaroux and Bréda 2002). Similarly, stem growth of A. saccharum trees declined following sugar removal from xylem sap, yet sugar concentration of NSC residual pools did not change (Isselhardt et al. 2016). Thus, reduced stem growth in drought years may be due to active regulation of mobile carbon pools at the expense of wood growth, but the relationships are complex and require further study.

Overall, drought sensitivity might be better viewed in terms of multiple variables (e.g., leaf abscission, NSC dynamics, stomatal sensitivity, rooting depth, and stomatal morphology), and not just stomatal sensitivity, that act together to prevent catastrophic losses in hydraulic functioning and carbon supply that are necessary to sustain vital physiological processes. While it is important to recognize that indicators of sensitivity vary greatly among species, adaptation to and phenotypic plasticity in response to local site conditions likely also play a critical, and perhaps even, dominant role in determining how Northeastern U.S. forests will respond to future drought conditions.

Integrating drought tolerance and sensitivity

Advancing our understanding of species’ abilities to survive drought (e.g., drought tolerance) requires measurement of short-term, physiological responses to drought associated with drought sensitivity, together with their long-term response to prolonged drought to assess mechanistic relationships between drought tolerance and sensitivity. While few such integrated studies have been conducted to date, evidence thus far highlight the paradox of greater drought-induced dieback and mortality for species that are classified as drought tolerant. For example, Hoffmann et al. (2011) showed that, contrary to expectation, isohydric (e.g., drought sensitive) species with lower wood density that were less resistant to cavitation experienced less canopy dieback during a short-term drought. The higher stomatal sensitivity and leaf abscission of isohydric species (A. rubrum, L. tulipifera, L. styraciflua) permitted greater safety margins, while avoiding catastrophic embolism (Hoffmann et al. 2011). In contrast, anisohydric species (e.g., drought insensitive) with greater wood density (Cornus florida, Q. alba, Q. rubra), smaller safety margins, and an inability to shed leaves experienced greater leaf desiccation and greater canopy dieback during droughts. Thus, leaf abscission and stomatal closure are important mechanisms that reduce transpiration and minimize the risk of cavitation for temperate deciduous species (Federer 1980; Roberts et al. 1980; Lucier and Hinckley 1982; Ginter-Whitehouse et al. 1983; Gu et al. 2007). Consistent with these findings, Gu et al. (2015) observed greater mortality of drought-tolerant Q. alba and Q. rubra compared with other drought-sensitive and intolerant species (A. saccharum, F. americana) following an extreme drought in 2012, which was primarily associated with the lack of regulation of predawn water potential of the drought-tolerant species.

There are several other cases where the drought tolerant and anisohydric Quercus spp. experienced higher mortality following drought compared with other co-occurring temperate deciduous species in the Northeastern U.S. and other regions (Karnig and Lyford 1968; Elliott and Swank 1994; Jenkins and Pallardy 1995; Pedersen 1998; Voelker et al. 2008), which further raises questions about confidence in drought-tolerance classifications. However, there are also cases where species that tend to be classified as drought intolerant (A. saccharum, F. americana) experienced localized and regional dieback associated with drought events (Hibben and Silverborg 1978; Hendershot and Jones 1989; Roy et al. 2004). Furthermore, species classified as drought tolerant with anisohydric behavior, such as Juniperus virginiana (Ginter-Whitehouse et al. 1983; Bahari et al. 1985), have been shown to experience lower mortality than other co-occurring species (Gu et al. 2015).

In the Northeastern U.S., it is rare that drought acts as the sole driver of tree mortality and dieback. There are many cases in the Northeastern U.S. where mortality and dieback are associated with multiple interacting factors including drought, insect defoliators, fungal pathogens, acid rain and subsequent depletion of soil Mg and Ca, atmospheric nitrogen deposition, and soil characteristics (Karnig and Lyford 1968; Hibben and Silverborg 1978; Hendershot and Jones 1989; Pitelka and Raynal 1989; Roy et al. 2004). A number of studies have reported drought and insect defoliation or pathogen interactions that resulted in mortality and dieback in Acer saccharum (Kolb and McCormick 1993), Fraxinus americana (Hibben and Silverborg 1978), and Quercus velutina (Karnig and Lyford 1968).

Anthropogenic alterations in biogeochemical cycling such as acid rain and increased atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the Northeastern U.S. can also interact with drought to cause forest dieback, particularly in high elevation Picea rubens. Long-term acidic deposition in the Northeastern U.S. resulted in major losses of calcium and magnesium from soils (Likens et al. 1996). Calcium plays an important role in many physiological processes in trees including signal transduction during periods of stress (i.e., temperature extremes, drought, and wounding), which is critical for acclimation to environmental stress and preventing mortality (Schaberg et al. 2001). Acid rain can also directly leach calcium from Picea rubens leaves, which can lead to delayed responses in stomatal closure during drought (Borer et al. 2005), potentially limiting mechanisms that prevent leaf desiccation. Deposition of fine particle ammonium (NH4 +) from the atmosphere is particularly high in high elevation sites in the Northeastern U.S. (Lovett and Lindberg 1993). Aber et al. (1989, 1998) hypothesized that nitrogen saturation may increase vulnerability of forests to drought-induced mortality because nitrogen saturation reduces fine-root biomass while increasing leaf biomass (e.g., increase in water demand and decrease in water supply). In support of this hypothesis, McNulty et al. (2017) observed greater Picea rubens mortality following a few droughts in nitrogen addition plots that were part of a 30-year nitrogen saturation experiment. Furthermore, McNulty et al. (2014) hypothesized that trees growing at high nutrient sites may actually be more vulnerable to drought-induced mortality than chronically stressed trees growing at nutrient poor sites. It is likely that future drought events, coupled with nitrogen availability, may limit the resiliency of high-elevation Picea rubens and Abies balsamea forests (McNulty et al. 2017).

One reason why drought-induced mortality events are rather rare in the Northeastern U.S. may be associated with the high buffering capacity of carbon stores in temperate deciduous trees (Hoch et al. 2003; Muhr et al. 2016). Non-structural carbohydrates are not only important for sustaining growth and respiration, they also play a key role in embolism repair (Zwieniecki and Holbrook 2009; Nardini et al. 2011) and in osmotic adjustments (Wang and Stutte 1992; Guicherd et al. 1997; Hartmann and Trumbore 2016) necessary for sustaining turgor pressure under drought conditions. While characteristics of drought sensitivity such as abscission and stomatal closure may reduce overall tree carbon supply, studies have concluded that temperate deciduous trees are not carbon-limited, even during years with heavy fruiting and longer growing seasons (Hoch et al. 2003; Körner 2003). In fact, Hoch et al. (2003) showed that temperate deciduous trees contained sufficient NSCs to replace canopy leaves four times. Similarly, Muhr et al. (2016) concluded that A. saccharum likely contains sufficient carbon reserves to buffer against periods of low carbon supply such as defoliation or drought. Thus, carbon-limitation under short-term drought may not be an issue for drought-sensitive species that actively regulate stem and leaf water potential at the expense of reductions in carbon reserves through stomatal closure and leaf abscission.

There is considerable uncertainty regarding the ability of plants to mobilize carbon pools that are readily available for sustaining growth and metabolic processes, particularly under persistent drought. One study found that A. rubrum preferentially used newer NSCs for metabolism and growth, particularly in the early spring, but older NSCs (>10 yrs. old) are still accessible (Carbone et al. 2013; Richardson et al. 2013). However, not all starches may be available for mobilization (Millard et al. 2007), and drought can adversely affect long-distance transport of carbon reserves (Sala et al. 2010, 2012). In France, Bréda et al. (2006) showed that reduced starch concentration in Q. petraea at the end of a dry summer resulted in greater branch dieback and incomplete budbreak and leaf-flushing the following spring; yet starch concentrations were not completely depleted. Similarly, new flushes of leaves in the spring did not occur in a declining F. sylvatica stand following periods of extreme waterlogging and drought despite having similar NSC concentrations in stems as compared with a healthy stand (Gérard and Bréda 2014). These results suggest that either leaf flushing is restricted at the expense of maintaining stored carbon reserves, or a proportion of stored starches within stems were not accessible during leaf-flushing. If carbon supply is in fact very large for species like A. saccharum, trees should be capable of using the large supply of carbon reserves following insect defoliation, but many A. saccharum trees in Quebec failed to produce healthy, vigorous leaves following defoliation (Roy et al. 2004). Thus, an important question related to carbon-limitation during drought is: How much of the stored NSCs are actually available for use in metabolic function during or following periods of drought?

There are many unresolved questions related to drought sensitivity and tolerance in Northeastern U.S. species. Species vulnerability to drought contributes to mortality and dieback and is ultimately determined by traits and responses associated with drought sensitivity and tolerance. However, the significance of drought vulnerability of Northeastern U.S. forests in mortality and dieback events still requires further investigation. In many cases of tree mortality and dieback, additional plant stressors such as insect defoliators, fungal pathogens, acid rain, nitrogen saturation, and soil characteristics likely interact with mechanisms associated with drought sensitivity and tolerance that exacerbate drought effects. Also, site-specific conditions (e.g., depth to bedrock, aspect, and soil drainage) that limit whole-tree carbon balance may predispose trees to mortality under drought conditions and biotic attacks. Trees growing at the fringes of their suitable habitat may be particularly vulnerable to reductions in growth and dieback (Horsley et al. 2002; Roy et al. 2004).

Future studies that examine these interactions between drought and other stressors may be fruitful as the likelihood of dieback and mortality appears to be greater when multiple stressors are involved. Past studies such as Ward et al. (2015) that have investigated multiple interacting factors including drought and nitrogen, observed greater reductions in transpiration in a combined treatment of fertilization and throughfall removal in Pinus taeda relative to the control and any single treatment (e.g., fertilization and throughfall removal). One suggested approach is to investigate drought responses in optimal and poor growing conditions for particular species. Many northern hardwood species like A. saccharum, F. americana, B. allegheniensis, and T. americana have high site requirements for growth and tend to occupy well- to moderately-drained till soils dominated by calcareous bedrock, but also grow at poorer sites dominated by granite with lower nutrient availability (Leak et al. 1987). Drought experiments (e.g., throughfall removal) at sites representing both of these edaphic characteristics are one example of studying drought at optimal and poor growing conditions. A few promising responses and traits to explore include the degree of isohydry/anisohydry, leaf morphology and anatomy, propensity for osmotic adjustments, wood density, vulnerability to cavitation, and drought-deciduous behavior. More importantly, developing our understanding of critical thresholds related to soil moisture, cavitation or embolism, and low carbon reserves during extreme drought is required to improve predictive modeling for responses to drought and will help to refine habitat and species distribution modeling (Iverson et al. 2008; Iverson et al. 2017).

Conclusions

Recent mesophication and declining importance of fire-adapted and drought tolerant genera like Quercus may not necessarily indicate that Northeastern U.S. forests are more vulnerable to drought. Many characteristics that reflect drought sensitivity in temperate deciduous species appear to be important for surviving short-term, extreme drought. Furthermore, there are a number of cases where drought-tolerant species experienced greater dieback or mortality than other co-occurring, drought-intolerant species. This pattern does not imply though that general classification of drought-tolerance is not useful. In fact, general classification schemes that assess species’ drought-tolerance using information about site conditions of where species typically grow is important, because adaptation to local site conditions strongly influences how species respond to drought. However, there is room to refine drought tolerance classification systems, as reliance on current classifications may lead to unexpected outcomes during extreme drought. Part of the solution to refining species drought-tolerance classification will likely involve future experiments that push trees past critical thresholds while measuring short-term physiological responses and specific drought-related traits for a number of species. Ideally, these experiments would include additional plant stressors (e.g., alterations in biogeochemical cycling, insect defoliation, fungal pathogens, shallow bedrock, and edaphic characteristics) to better understand potential drought interactions that lead to dieback and mortality.

References

Aber J, McDowell W, Nadelhoffer K, Magill A, Bernston G, Kamakea M, McNulty S et al (1998) Nitrogen saturation in temperate forest ecosystems. Bioscience 48:921–934

Aber JD, Federer CA (1992) A generalized, lumped-parameter model of photosynthesis, evaporation and net primary production in temperate and boreal forest ecosystems. Oecologia 92:463–474

Aber JD, Nadelhoffer KJ, Steudler P, Melillo JM (1989) Nitrogen saturation in northern forest ecosystems. Bioscience 39:378–386

Aber JD, Ollinger SV, Federer CA, Reich PB, Goulden ML, Kicklighter DW, Melillo JM et al (1995) Predicting the effects of climate change on water yield and forest production in the northeastern United States. Clim Res 5:207–222

Abrams MD (1988) Notes: genetic variation in leaf morphology and plant and tissue water relations during drought in Cercis canadensis L. For Sci 34:200–207

Abrams MD (1990) Adaptations and responses to drought in Quercus species of North America. Tree Physiol 7:227–238

Abrams MD (1994) Genotypic and phenotypic variation as stress adaptations in temperate tree species: a review of several case studies. Tree Physiol 14:833–842

Abrams MD, Gevel SVD, Dodson RC, Copenheaver CA (2000) The dendroecology and climatic impacts for old-growth white pine and hemlock on the extreme slopes of the Berkshire Hills, Massachusetts, USA. Can J Botany 78:851–861

Abrams MD, Kloeppel BD, Kubiske ME (1992) Ecophysiological and morphological responses to shade and drought in two contrasting ecotypes of Prunus serotina. Tree Physiol 10:343–355

Abrams MD, Kubiske ME, Mostoller SA (1994) Relating wet and dry year ecophysiology to leaf structure in contrasting temperate tree species. Ecology 75:123–133

Abrams MD, Kubiske ME, Steiner KC (1990) Drought adaptations and responses in five genotypes of Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh.: photosynthesis, water relations and leaf morphology. Tree Physiol 6:305–315

Abrams MD, Nowacki GJ (2016) An interdisciplinary approach to better assess global change impacts and drought vulnerability on forest dynamics. Tree Physiol 36:421–427

Adams HD, Luce CH, Breshears DD, Allen CD, Weiler M, Hale VC, Smith AMS et al (2012) Ecohydrological consequences of drought- and infestation-triggered tree die-off: insights and hypotheses. Ecohydrology 5:145–159

Allen CD, Macalady AK, Chenchouni H, Bachelet D, McDowell N, Vennetier M, Kitzberger T et al (2010) A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For Ecol Manag 259:660–684

Anderegg WRL, Flint A, Huang C-Y, Flint L, Berry JA, Davis FW, Sperry JS et al (2015) Tree mortality predicted from drought-induced vascular damage. Nat Geosci 8:367–371

Auclair AND, Lill JT, Revenga C (1996) The role of climate variability and global warming in the dieback of northern hardwoods. Water Air Soil Poll 91:163–186

Bahari ZA, Pallardy SG, Parker WC (1985) Photosynthesis, water relations, and drought adaptation in six woody species of oak-hickory forests in central Missouri. For Sci 31:557–569

Barbaroux C, Bréda N (2002) Contrasting distribution and seasonal dynamics of carbohydrate reserves in stem wood of adult ring-porous sessile oak and diffuse-porous beech trees. Tree Physiol 22:1201–1210

Battie-Laclau P, Laclau JP, Domec JC, Christina M, Bouillet JP, Cassia Piccolo M, Moraes Goncalves JL, et al (2014) Effects of potassium and sodium supply on drought-adaptive mechanisms in Eucalyptus grandis plantations. New Phytol 203:401–413

Bauerle WL, Whitlow TH, Setter TL, Bauerle TL, Vermeylen FM (2003) Ecophysiology of Acer rubrum seedlings from contrasting hydrologic habitats: growth, gas exchange, tissue water relations, abscisic acid and carbon isotope discrimination. Tree Physiol 23:841–850

Benjamin J, Lilieholm RJ, Damery D (2009) Challenges and opportunities for the northeastern forest bioindustry. J Forest 107:125–131

Boisvenue C, Running SW (2006) Impacts of climate change on natural forest productivity—evidence since the middle of the 20th century. Glob Change Biol 12:862–882

Bonan GB (2008) Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320:1444–1449

Booth RK, Jackson ST, Sousa VA, Sullivan ME, Minckley TA, Clifford MJ (2012) Multi-decadal drought and amplified moisture variability drove rapid forest community change in a humid region. Ecology 93:219–226

Borchert R, Pockman WT (2005) Water storage capacitance and xylem tension in isolated branches of temperate and tropical trees. Tree Physiol 25:457–466

Borer CH, Schaberg PG, DeHayes DH (2005) Acidic mist reduces foliar membrane-associated calcium and impairs stomatal responsiveness in red spruce. Tree Physiol 25:673–680

Bovard BD, Curtis PS, Vogel CS, Su HB, Schmid HP (2005) Environmental controls on sap flow in a northern hardwood forest. Tree Physiol 25:31–38

Bréda N, Huc R, Granier A, Dreyer E (2006) Temperate forest trees and stand under severe drought: a review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Ann For Sci 63:625–644

Burns RM, Honkala BH (1990) Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agricultural Handbook, Washington

Carbone MS, Czimczik CI, Keenan TF, Murakami PF, Pederson N, Schaberg PG, Xu X et al (2013) Age, allocation and availability of nonstructural carbon in mature red maple trees. New Phytol 200:1145–1115

Conkey LE (1979) Response of tree-ring density to climate in Maine, USA. Tree-Ring Bull 39:29–38

Cook ER, Jacoby GC (1977) Tree-ring-drought relationships in the Hudson Valley, New York. Science 198:399–401

Elliott KJ, Swank WT (1994) Impacts of drought on tree mortality and growth in a mixed hardwood forest. J Veg Sci 5:229–236

Federer C, Gee G (1976) Diffusion resistance and xylem potential in stressed and unstressed northern hardwood trees. Ecology 57:975–984

Federer CA (1980) Paper birch and white oak saplings differ in responses to drought. For Sci 26:313–324

Fisher RA, Williams M, da Costa AL, Malhhi Y, da Costa RF, Almeida S, Meir P (2007) The response of an Eastern Amazonian rain forest to drought stress: results and modelling analyses from a throughfall exclusion experiment. Glob Change Biol 13:2361–2378

Foster D, Aber J, Cogbill C, Hart C, Colburn E, D’Amato A, Donahue B et al (2010) Wildland and woodlands: a vision for the New England landscape. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Foster DR, Motzkin G, Slater B (1998) Land-use history as long-term broad-scale disturbance: regional forest dynamics in central New England. Ecosystems 1:96–119

Garcia-Forner N, Adams HD, Sevanto S, Collins AD, Dickman LT, Hudson PJ, Zeppel MJB et al (2016) Responses of two semiarid conifer tree species to reduced precipitation and warming reveal new perspectives for stomatal regulation. Plant Cell Environ 39:38–49

Gérard B, Bréda N (2014) Radial distribution of carbohydrate reserves in the trunk of declining European beech trees (Fagus sylvatica L.). Ann For Sci 71:675–682

Ginter-Whitehouse DL, Hinckley TM, Pallardy SG (1983) Spatial and temporal aspects of water relations of three tree species with different vascular anatomy. For Sci 29:317–329

Gu L, Pallardy SG, Hosman KP, Sun Y (2015) Drought-influenced mortality of tree species with different predawn leaf water dynamics in a decade-long study of a central US forest. Biogeosciences 12:2831–2845

Gu M, Rom CR, Robbins JA, Oosterhuis DM (2007) Effect of water deficit on gas exchange, osmotic solutes, leaf abscission, and growth of four birch genotypes (Betula L.) under a controlled environment. Hortscience 42:1383–1391

Guicherd P, Peltier JP, Gout E, Bligny R, Marigo G (1997) Osmotic adjustment in Fraxinus excelsior L.: malate and mannitol accumulation in leaves under drought conditions. Trees 11:155–161

Gustafson EJ, Sturtevant BR (2013) Modeling forest mortality caused by drought stress: implications for climate change. Ecosystems 16:60–74

Hartmann H, Trumbore S (2016) Understanding the roles of nonstructural carbohydrates in forest trees—from what we can measure to what we want to know. New Phytol 211:386–403

Hayhoe K, Wake CP, Huntington TG, Luo LF, Schwartz MD, Sheffield J, Wood E et al (2007) Past and future changes in climate and hydrological indicators in the US Northeast. Clim Dyn 28:381–407

Hendershot WH, Jones ARC (1989) Maple declines in Quebec: a discussion of possible causes and the use of fertilizers to limit damage. For Chron 65:280–287

Hibben CR, Silverborg SB (1978) Severity and causes of ash dieback. J Arboric 4:274–279

Hoch G, Richter A, Körner C (2003) Non-structural carbon compounds in temperate forest trees. Plant Cell Environ 26:1067–1081

Hoffmann WA, Marchin RM, Abit P, Lau OL (2011) Hydraulic failure and tree dieback are associated with high wood density in a temperate forest under extreme drought. Glob Change Biol 17:2731–2742

Horsley SB, Long RP, Bailey SW, Hallett RA, Wargo PM (2002) Health of eastern North American sugar maple forests and factors affecting decline. North J Appl For 19:34–44

Isselhardt ML, Perkins TD, van den Berg AK, Schaberg PG (2016) Preliminary results of sugar maple carbohydrate and growth response under vacuum and gravity sap extraction. For Sci 62:125–128

Iverson LR, Prasad AM, Matthews SN, Peters M (2008) Estimating potential habitat for 134 eastern US tree species under six climate scenarios. For Ecol Manag 254:390–406

Iverson LR, Thompson FR III, Matthews S, Peters M, Prasad A, Dijak WD, Fraser J et al (2017) Multi-model comparison on the effects of climate change on tree species in the eastern US: results from an enhance niche model and process-based ecosystem and landscape models. Landsc Ecol 32:1327–1346

Jenkins MA, Pallardy SG (1995) The influence of drought on red oak group species growth and mortality in the Missouri Ozarks. Can J For Res 25:1119–1127

Johnson AH (1983) Red spruce decline in the northeastern U.S.: hypotheses regarding the role of acid rain. J Air Pollut Control Assoc 33:1049–1054

Johnson DM, McCulloh KA, Meinzer FC, Woodruff DR, Eissenstat DM (2011) Hydraulic patterns and safety margins, from stem to stomata, in three eastern US tree species. Tree Physiol 31:659–668

Jones A, Hendershot W (1989) Maple decline in Quebec: a discussion of possible causes and the use of fertilizers to limit damage. For Chron 65:280–287

Jones HG (1992) Plants and microclimate: a quantitative approach to environmental plant physiology. Cambridge University Press, New York

Karnig JJ, Lyford WH (1968) Oak mortality and drought in the Hudson Highlands. Black Rock Forest Papers 29:1–13

Klein T (2014) The variability of stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential across tree species indicates a continuum between isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Funct Ecol 28:1313–1320

Kolb TE, McCormick LH (1993) Etiology of sugar maple decline in four Pennsylvania stands. Can J For Res 23:2395–2402

Körner C (2003) Carbon limitation in trees. J Ecol 91:4–17

Kubiske ME, Abrams MD (1992) Photosynthesis, water relations, and leaf morphology of xeric versus mesic Quercus rubra ecotypes in central Pennsylvania in relation to moisture stress. Can J For Res 22:1402–1407

Kubiske ME, Abrams MD (1994) Ecophysiological analysis of woody species in contrasting temperate communities during wet and dry years. Oecologia 98:303–312

Kubiske ME, Abrams MD, Mostoller SA (1996) Stomatal and nonstomatal limitations of photosynthesis in relation to the drought and shade tolerance of tree species in open and understory environments. Trees 11:76–82

Lambers H, Chapin FSC, Pons TL (2008) Plant physiological ecology. Springer, New York

Leak WB, Solomon DS, DeBald PS (1987) Silvicultural guide for northern hardwood types in the Northeast (revised). Research Paper NE-603, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station

Likens GE, Driscoll CT, Buso DC (1996) Long-term effects of acid rain: response and recovery of a forest ecosystem. Science 272:244–246

Loewenstein NJ, Pallardy SG (1998) Drought tolerance, xylem sap abscisic acid and stomatal conductance during soil drying: a comparison of canopy trees of three temperate deciduous angiosperms. Tree Physiol 18:431–439

Lovett GM, Lindberg SE (1993) Atmospheric deposition and canopy interactions of nitrogen in forests. Can J For Res 23:1603–1616

Lucier AA, Hinckley TM (1982) Phenology, growth and water relations of irrigated and non-irrigated black walnut. For Ecol Manag 4:127–142

Markesteijn L, Poorter L (2009) Seedling root morphology and biomass allocation of 62 tropical tree species in relation to drought- and shade-tolerance. J Ecology 97:311–325

Martin-Benito D, Pederson N (2015) Convergence in drought stress, but a divergence of climatic drivers across a latitudinal gradient in a temperate broadleaf forest. J Biogeogr 42:925–937

Martinez-Vilalta J, Poyatos R, Aguade D, Retana J, Mencuccini M (2014) A new look at water transport regulation in plants. New Phytol 204:105–115

Matthews SN, Iverson LR, Prasad AM, Peters MP, Rodewald PG (2011) Modifying climate change habitat models using tree species-specific assessments of model uncertainty and life history-factors. Forest Ecol Manag 262:1460–1472

McDowell N, Pockman WT, Allen CD, Breshears DD, Cobb N, Kolb T, Plaut J et al (2008) Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol 178:719–739

McNulty SG, Boggs JL, Aber JD, Rustad LE (2017) Spruce-fir forest changes during a 30-year nitrogen saturation experiment. Sci Total Environ 605–606:376–390

McNulty SG, Boggs JL, Sun G (2014) The rise of the mediocre forest: why chronically stressed trees may better survive extreme episodic climate variability. New Forest 45:403–415

Meinzer FC, Woodruff DR, Marias DE, Smith DD, McCulloh KA, Howard AR, Magedman AL (2016) Mapping ‘hydroscapes’ along the iso- to anisohydric continuum of stomatal regulation of plant water status. Ecol Lett 19:1343–1352

Mencuccini M, Minunno F, Salmon Y, Martinez-Vilalta J, Holtta T (2015) Coordination of physiological traits involved in drought-induced mortality of woody plants. New Phytol 208:396–409

Millard P, Sommerkorn M, Grelet GA (2007) Environmental change and carbon limitation in trees: a biochemical, ecophysiological and ecosystem appraisal. New Phytol 175:11–28

Muhr J, Messier C, Delagrange S, Trumbore S, Xu X, Hartmann H (2016) How fresh is maple syrup? Sugar maple trees mobilize carbon stored several years previously during early springtime sap-ascent. New Phytol 209:1410–1416

Namias J (1966) Nature and possible causes of the northeastern United States drought during 1962–65. Mon Weather Rev 94:543–554

Namias J (1967) Further studies of drought over northeastern United States. Mon Weather Rev 95:497–508

Nardini A, Lu Gullo MA, Salleo S (2011) Refilling embolized xylem conduits: is it a matter of phloem unloading? Plant Sci 180:604–611

Niinemets Ü, Valladares F (2006) Tolerance to shade, drought, and waterlogging of temperate Northern Hemisphere trees and shrubs. Ecol Monogr 76:521–547

Nowacki GJ, Abrams MD (2008) The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. Bioscience 58:123–138

Nowacki GJ, Abrams MD (2015) Is climate an important driver of post-European vegetation change in the Eastern United States? Glob Change Biol 21:314–334

O’Brien EA (2006) A question of value: what do trees and forests mean to people in Vermont? Landsc Res 31:257–275

Ollinger SV, Aber JD, Reich PB (1997) Simulating ozone effects on forest productivity: interactions among leaf-, canopy-, and stand-level processes. Ecol Appl 7:1237–1251

Pallardy SG, Rhoads JL (1993) Morphological adaptations to drought in seedlings of deciduous angiosperms. Can J For Res 23:1766–1774

Pallardy SG (2008) Physiology of wood plants. Elsevier, Burlington

Parker WC, Pallardy SG (1985) Genotypic variation in tissue water relations of leaves and roots of black walnut (Juglans nigra) seedlings. Physiol Plant 64:105–110

Parker WC, Pallardy SG, Hinckley TM, Teskey RO (1982) Seasonal changes in tissue water relations of three woody species of the Quercus-Carya forest type. Ecology 63:1259–1267

Payette S, Fortin M, Morneau C (1996) The recent sugar maple decline in southern Quebec: probable causes deduced from tree rings. Can J For Res 26:1069–1078

Pedersen BS (1998) The role of stress in the mortality of Midwestern oaks as indicated by growth prior to death. Ecology 79:79–83

Pederson N, Bell AR, Cook ER, Lall U, Devineni N, Seager R, Eggleston K et al (2013) Is an epic pluvial masking the water insecurity of the greater New York City region? J Clim 26:1339–1354

Pederson N, D'Amato AW, Dyer JM, Foster DR, Goldblum D, Hart JL, Hessl AE et al (2015) Climate remains an important driver of post-European vegetation change in the eastern United States. Glob Change Biol 21:2105–2110

Peters MP, Iverson LR, Matthews SN (2015) Long-term droughtiness and drought tolerance of eastern US forests over five decades. Forest Ecol Manag 345:56–64

Phillips RP, Ibáñez I, D’Orangeville HPJ, Ryan MG, McDowell NG (2016) A belowground perspective on the drought sensitivity of forests: towards improved understanding and simulation. Forest Ecol Manag 380:309–320

Pitelka LF, Raynal DJ (1989) Forest decline and acidic deposition. Ecology 70:2–10

Rennenberg H, Dannenmann M (2015) Nitrogen nutrition of trees in temperate forests—the significance of nitrogen availability in the pedosphere and atmosphere. Forests 6:2820–2835

Richardson AD, Carbone MS, Keenan TF, Czimczik CI, Hollinger DY, Murakami P, Schaberg PG et al (2013) Seasonal dynamics and age of stemwood nonstructural carbohydrates in temperate forest trees. New Phytol 197:850–861

Roberts SW, Strain BR, Knoerr KR (1980) Seasonal patterns of leaf water relations in four co-occurring forest tree species: parameters from pressure-volume curves. Oecologia 46:330–337

Roman D, Novick K, Brzostek E, Dragoni D, Rahman F, Phillips R (2015) The role of isohydric and anisohydric species in determining ecosystem-scale response to severe drought. Oecologia 179:641–654

Roy G, Larocque GR, Ansseau C (2004) Retrospective evaluation of the onset period of the visual symptoms of dieback in five Appalachian sugar maple stand types. For Chron 80:375–383

Roy G, Larocque GR, Ansseau C (2006) Prediction of mortality in Appalachian sugar maple stands affected by dieback in southeastern Quebec, Canada. Forest Ecol Manag 228:115–123

Sala A, Piper F, Hoch G (2010) Physiological mechanisms of drought-induced tree mortality are far from being resolved. New Phytol 186:274–281

Sala A, Woodruff DR, Meinzer FC (2012) Carbon dynamics in trees: feast or famine? Tree Physiol 32:764–775

Schaberg PG, DeHayes DH, Hawley GJ (2001) Anthropogenic calcium depletion: a unique threat to forest ecosystem health? Ecosyst Health 7:214–228

Siccama TG, Bliss M, Vogelmann HW (1982) Decline of red spruce in the Green Mountains of Vermont. B Torrey Bot Club 109:162–168

Simonin K, Kolb TE, Montes-Helu M, Koch GW (2007) The influence of thinning on components of stand water balance in a ponderosa pine forest stand during and after extreme drought. Agric For Meteorol 143:266–276

Skelton RP, West AG, Dawson TE (2015) Predicting plant vulnerability to drought in biodiverse regions using functional traits. P Natl Acad Sci 112:5744–5749

Skov KR, Kolb TE, Wallin KF (2004) Tree size and drought affect ponderosa pine physiological response to thinning and burning treatments. For Sci 50:81–91

Sperry J, Hacke U, Oren R, Comstock J (2002) Water deficits and hydraulic limits to leaf water supply. Plant Cell Environ 25:251–263

Tardieu F, Simonneau T (1998) Variability among species of stomatal control under fluctuating soil water status and evaporative demand: modelling isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. J Exp Bot 49:419–432

Tschaplinski TJ, Gebre GM, Shirshac TL (1998) Osmotic potential of several hardwood species as affected by manipulation of throughfall precipitation in an upland oak forest during a dry year. Tree Physiol 18:291–298

Tyree MT, Cochard H, Cruiziat P, Sinclair B, Ameglio T (1993) Drought-induced leaf shedding in walnut: evidence for vulnerability segmentation. Plant Cell Environ 16:879–882

Urbanski S, Barford C, Wofsy S, Kucharik C, Pyle E, Budney J, McKain K et al (2007) Factors controlling CO2 exchange on timescales from hourly to decadal at Harvard Forest. J Geophys Res 112:G02020. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JG000293

USDA, NRCS (2017) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 12 June 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro

Voelker SL, Muzika R-M, Guyette RP (2008) Individual tree and stand level influences on the growth, vigor, and decline of red oaks in the Ozarks. For Sci 54:8–20

Wake, CP, Burakowski E, Wilkinson P, Hayhoe K, Stoner A, Keeley C, LaBranche J (2014) Climate change in northern New Hampshire: past, present, and future. Climate Solutions New England Report, Sustainability Institute at the University of New Hampshire. http://climatesolutionsne.org

Wang Z, Stutte GW (1992) The role of carbohydrates in active osmotic adjustment in apple under water stress. J Amer Soc Hort Sci 117:816–823

Ward EJ, Domec JC, Laviner MA, Fox TR, Sun G, McNulty S, King J et al (2015) Fertilization intensifies drought stress: water use and stomatal conductance of Pinus taeda in a midrotation fertilization and throughfall reduction experiment. Forest Ecol Manag 355:72–82

Woodbury PB, Smith JE, Heath LS (2007) Carbon sequestration in the U.S. forest sector from 1990 to 2010. Forest Ecol Manag 241:14–27

Wullschleger SD, Hanson PJ, Tschaplinski TJ (1998) Whole-plant water flux in understory red maple exposed to altered precipitation regimes. Tree Physiol 18:71–79

Yi K, Dragoni D, Phillips RP, Roman DT, Novick KA (2017) Dynamics of stem water uptake among isohydric and anisohydric species experiencing a severe drought. Tree Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpw126

Zwieniecki MA, Holbrook NM (2009) Confronting Maxwell’s demon: biophysics of xylem embolism repair. Trends Plant Sci 14:530–534

Acknowledgements

Research was sponsored by the University of New Hampshire-New Hampshire Agriculture Experiment Station. We thank everyone in the University of New Hampshire Ecohydrology lab for helpful comments and suggestions on the concepts and information presented in this review. We also thank Dr. Melinda Smith for helpful comments during early discussions of this review paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the reviews and discussions on drought tolerance and sensitivity of Northeastern U.S. tree species. AC led the writing with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Coble, A.P., Vadeboncoeur, M.A., Berry, Z.C. et al. Are Northeastern U.S. forests vulnerable to extreme drought?. Ecol Process 6, 34 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0100-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0100-x