Abstract

Background

Overweight and obesity are increasing in low- and middle-income countries, while underweight remains a significant health problems. However, the association between double burden of nutrition and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes is still unclear in Bangladesh. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of maternal undernutrition and excessive body weight on a range of maternal and child health outcomes.

Methods

In this study, we used Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2011 and 2014 data sets to cover the maternal, child and non-communicable diseases related health outcomes. The study considered a range of outcome variables including pregnancy complication, cesarean delivery, diabetes, hypertension, stunting, and wasting, low birth weight, genital discharge, genital sore/ulcer, stillbirth, early neonatal mortality, perinatal mortality, preterm birth and prolonged labor. The key exposure variable was maternal body mass index. Multilevel regression analysis was performed to examine the association between outcomes and exposure variables.

Results

Maternal overweight and obesity has increased from 10% in 2004 to 24% in 2014, a 240% increase in 10 years. Between 2004 and 2014, maternal undernutrition declined from 33% to 18%, a reduction rate of only 54% in 10 years. Compared to normal-weight women, overweight and obese women were more likely to have experienced pregnancy complication, cesarean delivery, diabetes, and hypertension. Underweight women were 1.3 times more likely to have children with stunting and 1.6 times more likely to experience wasting compared to normal weight women. Maternal BMI was not significantly associated with increased risk of genital sore or ulcer, genital discharge, menstrual irregularities, or low birth weight though in certain cases risk was higher.

Conclusions

High maternal overweight and obesity were observed to have significant adverse effects on health outcomes, while underweight was a risk factor for newborn health. The findings show that weight management is necessary to prevent adverse birth and health outcomes in Bangladesh.

Trial registration

Data related to health was collected by following the guidelines of ICF international and Bangladesh Medical Research Council. The registration number of data collection is 132989.0.000 and the data-request was registered on March 11, 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, overweight and obesity increasing rapidly especially in low- and lower middle- income countries. It has risen to 27.5% between 1980 and 2013 worldwide [1]. If secular trends continue, by 2030 there will be 2.16 billion overweight and 1.12 billion obese [2]. Overweight and obesity has become a major health problem both in developed and in developing countries. High-income countries reported more than double prevalence of obesity than low- and lower middle- income countries [3]. Men in developed countries were more overweight and obese, whereas in developing countries, overweight and obesity were more prevalent in women [3].

A wide variation of high BMI was observed between regions, country income categories and age-sex distribution [4]. High BMI was more prevalent in the American region (62% for overweight in both sexes, and 26% for obesity) and bit lower in the South East Asia region (14% overweight in both sexes and 3% for obesity) [5]. Asian countries have some of the lowest prevalence’s of overweight and obesity, but prevalence rates are increasingly rapidly [6, 7]. The boom in economic development and cultural factors are often cited as drivers. Almost one-half of the Indian adults living in urban area are overweight and obese [8]. Similar nutritional shifts were also observed during the last few decades in Asian countries including Pakistan [9], Nepal [10], and Bangladesh [11]. This may incur a high burden of nutrition-related diseases in these countries.

The growing epidemic of maternal overweight/obesity accounted for 1.1 million deaths in 1990, and 1.7 million deaths in 2010 [12, 13]. It is clear from the previous studies that maternal underweight, overweight or obesity are a threat to maternal and infant health [14,15,16]. For instance, high maternal BMI has closely related to gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, cesarean section, preeclampsia, gestational age, preterm birth, fetal death, still birth, perinatal death, neonatal death, and infant death. The results are not consistent across studies. Some found higher risk and some lower risk of birth outcomes in connection to BMI. This discrepancy may be due small sample size, study design, regional variation, or country income categories [17].

Furthermore, like many developed countries, overweight and obesity are also increasing rapidly in Bangladesh. Despite this growing burden of BMI, very few studies have been conducted to date to examine the association between dual burden of maternal BMI and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes [18,19,20]. Most of these studies are limited to specific adverse outcomes and found mixed results between BMI and risk of maternal health outcomes. For instance, overweight and obesity was positively associated with risk of diabetes [21], and hypertension [22]. However, others found no significant association [23]. No study examined a comprehensive range of maternal health and birth outcomes in relation to maternal BMI using population based survey data. Thus, the present study is seeking to examine the association between maternal undernutrition and excessive body weight and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes.

Methods

Sources of data

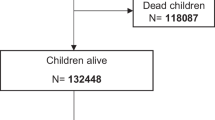

This study is based on a cross-sectional data from Bangladesh Demographic and Health survey (BDHS) – 2014. All information including socio-economic, demographic, anthropometric, birth and health characteristics were collected from 17,863 women aged 15 to 49 years. The key exclusion criteria were women having no children (n = 1,784), pregnant women in their second (13 weeks to 28 weeks of pregnancy) or third trimester (from 28 weeks of pregnancy to termination of pregnancy) (n = 475), and women who have not given birth in the last five years (n = 8,967). Non-response related to BMI (n = 53), pregnancy complications (n = 4), genital sore or ulcer (n = 9), occupation (n = 1) and number of antenatal visit (n = 5) were also excluded from the analysis. The final effective sample for analysis was 6,584. The participant’s selection framework is presented in Fig. 1. In addition, BDHS– 2011 data were extracted for diabetes, hypertension, preterm birth and prolonged labor.

Exposure variable

The exposure variable in this study was maternal BMI. It was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared. The details measurements of women heights and weights were described in DHS website [24]. Using the World Health Organization (WHO) cut-off points, maternal BMI was categorized as:<18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (normal weight), 25–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) and ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese).

Outcome variables

The study included a wide range of outcome variables including pregnancy complications (health problem during pregnancy that adversely affect mothers and fetus), pregnancy termination (termination of fetus before capable of independent life), genital sore/ulcer (bumps and lesions around the vagina), genital discharge (discharge thick, pasty, thin, cloudy, bloody liquid from the vagina), menstrual irregularities (menstrual cycle does not ranged between 21–35 days), cesarean delivery (surgical procedure of childbirth),diabetes (FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L) and hypertension (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg/ DBP ≥ 90 mmHg). Birth weight (babies born with weight <2500 g), stunting (child is shorter than for age), wasting (child weight is low as compared to height), early neonatal mortality (deaths at age 0–7 days), stillbirths (fetal death in pregnancies lasting seven or more months), perinatal mortality (fetal death after 7 months of pregnancy to first seven days of live born), preterm birth (<37 weeks of gestation) and prolonged labor (labor pain >12 h) were included as birth outcomes.

Confounding adjustment

Different individual, household and community level characteristics were included in analysis as confounding adjustment variables. The variables were age (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥40), respondents’ education (no formal education, primary, secondary, and higher education), spouse’s education, socio-economic status (poorest, poorer, average, richer, richest), region (southern, southeastern, central, western, mid-western, northwestern, eastern), place of residence (urban, rural), present working status (yes, no), and number of antenatal visits (no visit, less than or equal four visit, above four visit). We included diarrhea and acute respiratory infection in the adjusted models for stunting and wasting, as many previous studies found this variable significantly associated with child malnutrition.

Statistical analysis

We used mean and frequency distributions to describe participant characteristics. We also estimated the prevalence of underweight and overweight by selected socio-demographic characteristics. Individual women were nested within household, households were nested within cluster/primary sampling unit, and clusters were nested within region. To account for multiple hierarchy and dependency in data, we performed multilevel (three levels) logistic regression models to examine the association between each outcome variable and BMI. Multilevel Poisson regression models were used when model convergence issues arose in the case of rare events. The initial model included only specific outcomes and BMI and the final model was adjusted for all potential confounding factors. All analyses accounted for probability sample design and we used Stata software version 13.1.

Results

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the crude characteristics of the study subjects. We analyzed 6,584 married women who reported at least one birth within five years preceding the survey. On average, maternal age was 25.65 years. The crude mean BMI was 21.67 kg/m2 and systolic blood pressure was and 121.47 mmHg. The prevalence of diabetes and hypertension was 10% and 32% respectively. Around 47% maternal women reported pregnancy complication. Prevalence of low birth weight was 20%, cesarean delivery was 25% and pregnancy termination was 16%. Around 37% reported having a child with stunting and 14.4% reported a child with wasting.

Trend of underweight and overweight and obesity

Figure 2 presents the trends of underweight and overweight and obesity. The prevalence of underweight women decreased by around 15 percentage points (from 33% in 2004 to 18% in 2014). Additionally, prevalence of overweight and obese increased by 14 percentage points (from 10% in 2004 to 24% in 2014).

Age-specific prevalence of BMI

Age-specific prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity is presented in Fig. 3. Significant variation observed in the prevalence of BMI across age categories. Higher prevalence of underweight (33.8%) and overweight (34.6%) was reported among women aged 20–24 years and 25–29 years, respectively.

Socio-economic differentials of BMI

Prevalence of BMI across women’s educational levels is presented in Fig. 4. The detailed prevalence of BMI according to the various demographic and socio economic characteristics is presented in Additional file: Table S1. Higher prevalence of underweight was found among women with primary (33.8%) and secondary education (41.5%). Overweight and obesity were considerably higher in women with secondary and higher education. So secondary school educated women were both at the higher risk of under- and over nutrition. Similar to women’s education level, women with higher educated husbands were also more likely to experience a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity. Noticeable regional variation of underweight and overweight prevalence was found in our study. More than one third of women in central city (Dhaka) were overweight and obese. Comparatively, a low prevalence of underweight women (6%) was observed in the Southern region (Barisal) (7%). In general, rural women were more likely to be underweight (82%) and urban women were more likely to be obese (48%). The result also shows that there was variation in underweight and overweight and obese among women across socio-economic status. Wealthy women were mainly overweight (40.8%) and obese (51.4%) and disadvantaged women were mainly underweight.

Maternal BMI and risk of birth and health outcome

To assess the association between maternal BMI and birth and health outcomes, we performed a series of unadjusted and adjusted multilevel logistic models. The results of unadjusted and adjusted models for specific health and birth outcomes are shown in Tables 2 and 3. We performed likelihood test to choose preferable models. The tests compared random effects model against fixed effects model and found statistically significant results (p < 0.05). This implied the random effect models were necessary to perform clustering data.

The results indicated that pregnancy complications were higher among obese (adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 2.05; 95% CI, 1.24-3.37) women than normal-weight women. The risk of pregnancy termination was relatively higher in overweight and obese women than the normal weight women; however, the association was statistically insignificant. We did not find any significant association between maternal BMI and risk of genital sore/ulcer, genital discharge, menstrual irregularities, and low birth weight. Both unadjusted and adjusted models showed that maternal BMI was positively associated with diabetes, hypertension, and cesarean delivery.

Overweight and obese women had 1.67 times (95% CI, 1.00-2.82) and 1.71 times (95% CI, 1.02-3.31) higher risk, respectively, for cesarean delivery as compared to normal-weight women. The fully adjusted model showed that overweight women were 2.58 times (95% CI, 1.81-3.68) more likely of developing diabetes than normal-weight women. As compared to normal-weight women, overweight and obese women were 2.29 times (95% CI, 1.60-3.29) and 4.12 times (95% CI, 1.88-9.06) higher risk of developing hypertension, respectively.

The multilevel logistic regression results indicated that the risk of stunting and wasting was 1.29 times (95% CI, 1.11-1.40) and 1.59 times (95% CI, 1.13-1.80) higher, respectively, among underweight women than normal weight women. However, overweight and obese women played a protective role against stunting and wasting. Both underweight and overweight or obese women were lower risk of preterm birth compared to normal weight women. Compared to normal weight women, the risk of prolong delivery was higher among overweight and obese (adjusted risk ratio (ARR), 7.57; 95% CI, 1.26-45.43) women. Overweight and obese women were higher risk of stillbirths (ARR, 3.20; 95% CI, 0.77-13.55), early neonatal mortality (ARR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.50-4.07) and perinatal mortality (ARR, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.64-4.89). However, these increased risks were not statistically significant.

Discussion

This is the first nationally representative cross-sectional study in Bangladesh that has demonstrated the risk of birth and health outcomes in connection to maternal BMI. The findings suggest that between 2004 and 2014, maternal overweight and obesity increased to 240% in Bangladesh, while undernutrition declined to 54%. Maternal overweight or obese increased risk of pregnancy complication, cesarean delivery, diabetes, and hypertension and prolonged labor. The study also found that the risk of stunting and wasting was higher among underweight women than normal weight women.

In general, over time the prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing and underweight is decreasing. In 2014, prevalence of underweight and overweight was 21.9% and 15.6%, respectively. This situation represents a double burden of nutrition condition that exists among women in Bangladesh. Similar nutritional problems are also observed in India [25], and others developing countries [26,27,28]. There was an apparent socio-economic, demographic and regional distribution of underweight and overweight or obese. Women in low socio-economic status, with little or no education and rural residence experienced greater risk of underweight. Conversely, higher educated women, wealthier women and those residing in urban areas had higher prevalence of overweight and obesity. This is consistent with previous studies from many settings including Bangladesh [29], and others South Asian countries [25, 30].

Over the last few decades, Bangladesh has substantially reduced maternal mortality [31, 32]. In addition, infant and neonatal mortality, and total fertility rates have also declined sharply since 1990. An estimated 11,000-21,000 mothers die each year in Bangladesh due to the pregnancy related complication [33], and a further 320,000 women suffer from the injuries or disabilities caused by these complication during pregnancy and child birth [34]. Available findings suggest that controlling weight may significantly reduce the number of pregnancy complication. Thus individual and national level awareness about such adverse effect of overweight and obesity may lead to reduce the number of pregnancy complication which ultimately crop the frequency of mothers death and disabilities.

The association between diabetes and overweight (or obesity) in general population is well established in Bangladesh [35, 36], and other countries [37, 38]. However, comprehensive assessment especially among women is still lacking in Bangladesh. Study results indicate that overweight and obesity have an increased risk of developing diabetes among women in Bangladesh. Additionally this study found a substantially higher proportion of hypertension among overweight and obese women, a finding supported by others studies [39, 40]. A recent meta-analysis based on low- and lower middle-income countries also found the positive association between the maternal overweight and obesity with gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and post partum haemarroage [17]. All of these non-communicable diseases have become leading risk factors for deaths and disability in developing and developed countries [12]. In 2010, hypertension accounted for 2.9 million deaths among women (6% of total Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs)), high fasting plasma glucose accounted for 1.1 million deaths (3% of DALYs), ischemic heart diseases accounted for 1.7 million deaths (3% of DALYs), and stroke accounted for 2.0 million deaths (4% of DALYs) in developing countries [13].

Consistent with previous studies [41, 42], overweight and obese women were more likely to have cesarean delivery in our study. Weight management is important for every woman in reproductive age. Women with a normal BMI should strive for maintenance of a healthy weight, whereas underweight and overweight women should aim to healthy weight prior to the pregnancy. These contribute to reduce the effect of high maternal BMI on labor and delivery complications and cesarean delivery [42].

On average, the study found 15 stillbirths and 37 early neonatal deaths per 1000 live births. This is consistent with other low- and lower middle-income countries [43, 44]. Deaths during the neonatal period contribute around 38% of the total under five deaths [44]. The main causes of neonatal death are preterm birth (28%), severe infection (26%) and low birth weight (31%) [44, 45]. Complication during pregnancy and delivery is also another important determinant of neonatal survival [46]. The risk of overweight and obesity on these adverse outcomes is well known which greatly contribute to the increased risk of stillbirth, early neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality. Consistent with previous literature [47, 48], obese women were more likely to experience stillbirth, early neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality. Thus, it is necessary to emphasis-that women control their weight and reduce levels of overweight or obesity to reduce these adverse birth outcomes.

Similar to some previous studies [49, 50], overweight and obese women were more likely to have prolonged labor, which may lead to maternal and newborn death and disability [51]. It may also result in increased risk of cesarean delivery and maternal complication following ruptured membranes, trauma to the bladder, and ruptured uterus with consequent haemorrhage [52]. In this study, both underweight and overweight or obese women were less likely to experience preterm birth compared to normal-weight women. This is inconsistent with other studies conducted in Ireland [53], Spain [42], South Australia [54], and China [55]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis also found underweight women have higher risk of preterm birth [17]. This contradictory finding in our study may be due to the small number of cases was extracted from the verbal autopsy record. Our study indicated that underweight women were at increased risk of stunting and wasting children. However, overweight or obesity plays a protective role against stunting and wasting among children

The key strength of this study was the availability of a large, nationally representative dataset providing the sufficient power to investigate the adverse birth and health outcome related to maternal BMI. The use of STROBE checklist strengthened our paper (Additional file 1: Table S2). However, we were unable to establish a causal relationship between the maternal BMI and birth and health outcomes as a result of cross sectional study design. Secondly, BMI should be measured either before pregnancy or in the first trimester; however, BDHS collected women height and weight information during interview and birth outcomes were recorded within last three years. Since BMI is not stable over time, which may lead to partially bias the association between exposure and outcomes. To address this limitation, we exclude women with substantial fluctuation of BMI. Furthermore, we see reassuringly that the direction and magnitude of effect of BMI as a function of time elapsed between the index of birth and survey is similar in women with adverse birth or health outcomes, and would if anything have led to underestimate of effect. These findings suggest that misclassification bias of BMI is likely to be small. A previous study published in Lancet also found the little misclassification bias of BMI in a similar study design [56]. Finally, information about a majority of the outcome variables (except diabetes and hypertension) were self-reported. However, the DHS has been collecting data in low-income settings by similar methods for more than two decades, and there has been a substantial improvement in the completeness and reliability of the dataset [57].

Conclusions

Our findings represent a clear picture of the adverse birth and health outcome that are related to maternal BMI. Higher risk of pregnancy complication, prolonged labor, cesarean delivery, diabetes, and hypertension was found among overweight or obese women. On the other hand, higher odds of stunting, and wasting were found among underweight women. Therefore, weight management is necessary to prevent adverse birth and health outcomes. Clinicians and other healthcare providers and policy maker should counsel women prior to or in early pregnancy on adverse threats of underweight, overweight, or obesity on their own and their infant’s health. Informed women could try to optimize their BMI before conception.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81.

Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes. 2008;32(9):1431–7.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81.

Aimukhametova G, Ukybasova T, Hamidullina Z, Zhubanysheva K, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Yoshida Y, Kasuya H, Sakamoto J. The impact of maternal obesity on mother and neonatal health: study in a tertiary hospital of Astana, Kazakhstan. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012;74(1–2):83–92.

World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41.

Sidik SM, Rampal L. The prevalence and factors associated with obesity among adult women in Selangor, Malaysia. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2009;8(1):2.

Gupta R, Sharma K, Gupta A, Agrawal A, Mohan I, Gupta V, Khedar R, Guptha S. Persistent high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the urban middle class in India: Jaipur Heart Watch-5. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:11–6.

Abbas M, Paracha PI, Khan S, Iqbal Z, Iqbal M. Socio-demographic and dietary determinants of overweight and obesity in male pakistani adults. Eur Sci J. 2013;9(33):470–86.

Acharya B, Chauhan HS, Thapa SB, Kaphle HP, Malla D. Prevalence and socio-demographic factors associated with overweight and obesity among adolescents in Kaski district, Nepal. Indian J Comm Health. 2014;26(6):118–22.

Bhuiyan MU, Zaman S, Ahmed T. Risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among urban school children and adolescents in Bangladesh: a case–control study. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):72.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation HDN. The global burden of disease: generating evidence, guiding policy– South Asia regional edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Joshi S, Unni J, Vijay S, Khanijo V, Gupte N, Divate U. Obesity and pregnancy outcome in a private tertiary hospital in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114(1):82–3.

Xu X, Ding X, Zhang X, Su S, Treiber FA, Vlietinck R, Fagard R, Derom C, Gielen M, Loos RJ, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on blood pressure variability: a study in twins. J Hypertens. 2013;31(4):690–7.

Safavi Ardabili N KZ, Kariman NS. The association between maternal body mass index during first trimester of pregnancy with low birth weight. Obes Rev. 2011;5:63–279.

Rahman M, Abe S, Kanda M, Narita S, Rahman M, Bilano V, Ota E, Gilmour S, Shibuya K. Maternal body mass index and risk of birth and maternal health outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(9):758–70.

Hosain GM, Chatterjee N, Begum A, Saha SC. Factors associated with low birthweight in rural Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52(2):87–91.

Ferdous J, Ahmed A, Dasgupta S, Jahan M, Huda F, Ronsmans C, Koblinsky M, Chowdhury M. Occurrence and determinants of postpartum maternal morbidities and disabilities among women in Matlab, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(2):143.

Rahman M, Poudel KC, Yasuoka J, Otsuka K, Yoshikawa K, Jimba M. Maternal exposure to intimate partner violence and the risk of undernutrition among children younger than 5 years in Bangladesh. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1336–45.

Rahman MS, Akter S, Abe SK, Islam MR, Mondal M, Rahman J, Rahman MM. Awareness, treatment, and control of diabetes in Bangladesh: a nationwide population-based study. PloS one 2015;10(2):e0118365.

Zaman MM, Bhuiyan MR, Karim MN, Rahman MM, Akanda AW, Fernando T. Clustering of non-communicable diseases risk factors in Bangladeshi adults: an analysis of STEPS survey 2013. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):659.

Asghar S, Khan AKA, Ali SMK, Sayeed MA, Bhowmik B, Diep ML, Shi Z, Hussain A. Incidence of diabetes in Asian-Indian subjects: a five year follow-up study from Bangladesh. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5(2):117–24.

Demographic and health survey (DHS) database. DHS, The united States of America, 2015. Available in http://dhsprogram.com.

Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Khan KT. Do burdens of underweight and overweight coexist among lower socioeconomic groups in India? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(2):369–76.

Janghorbani M, Amini M, Willett WC, Mehdi Gouya M, Delavari A, Alikhani S, Mahdavi A. First nationwide survey of prevalence of overweight, underweight, and abdominal obesity in Iranian adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(11):2797–808.

Ly KA, Ton TG, Ngo QV, Vo TT, Fitzpatrick AL. Double burden: a cross-sectional survey assessing factors associated with underweight and overweight status in Danang, Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:35.

Jaacks LM, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Recent underweight and overweight trends by rural–urban residence among women in low- and middle-income countries. J Nutr. 2015;145(2):352–7.

Rahman MS, Mondal MNI, Islam MR, Ahmed KM, Karim MR, Alam MS. Under weightiness among ever-married non-pregnant women in Bangladesh: a population based study. Univ J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;3(2):29–36.

Jayawardena R, Byrne NM, Soares MJ, Katulanda P, Hills AP. Prevalence, trends and associated socio-economic factors of obesity in South Asia. Obes Facts. 2013;6(5):405–14.

El Arifeen S, Hill K, Ahsan KZ, Jamil K, Nahar Q, Streatfield PK. Maternal mortality in Bangladesh: a countdown to 2015 country case study. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1366–74.

World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010:WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, WB estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

World Health Organization. World health report 2005: make every mother and child count. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Koblinsky M, Anwar I, Mridha MK, Chowdhury ME, Botlero R. Reducing maternal mortality and improving maternal health: Bangladesh and MDG 5. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(3):280.

Talaei M, Sadeghi M, Marshall T, Thomas G, Iranipour R, Nazarat N, Sarrafzadegan N. Anthropometric indices predicting incident type 2 diabetes in an Iranian population: the Isfahan Cohort Study. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):424–31.

Akter S, Rahman MM, Abe SK, Sultana P. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes and their risk factors among Bangladeshi adults: a nationwide survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(3):204–13A.

Agrawal P, Gupta K, Mishra V, Agrawal S. Women's health in India: the role of body mass index. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(3):320–41.

Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):275–86.

Dua S, Bhuker M, Sharma P, Dhall M, Kapoor S. Body mass index relates to blood pressure among adults. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(2):89–95.

Kaushal K. Obesity and consensus statement: a comment on body mass index relates to blood pressure among adults. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(4):187.

Lynch C, Sexton D, Hession M, Morrison JJ. Obesity and mode of delivery in primigravid and multigravid women. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(3):163–7.

Fyfe EM, Thompson JM, Anderson NH, Groom KM, McCowan LM. Maternal obesity and postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal and caesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):112.

Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, Creanga AA, Tunçalp Ö, Balsara ZP, Gupta S. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1319–30.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Team LNSS. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365(9462):891–900.

Mathers CD, Boerma T, Fat DM. Global and regional causes of death. Br Med Bull 2009;92:7–32.

Gold K, Mozurkewich E, Puder K, Treadwell M. Maternal complications associated with stillbirth delivery: a cross-sectional analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol 2015:1–5.

Nahar S, Rahman A, Nasreen HE. Factors influencing stillbirth in Bangladesh: a case–control study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27(2):158–64.

Kusiako T, Ronsmans C, Van der Paal L. Perinatal mortality attributable to complications of childbirth in Matlab, Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(5):621–7.

Wolfe KB, Rossi RA, Warshak CR. The effect of maternal obesity on the rate of failed induction of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):128. e1-. e7.

Carlhäll S, Källén K, Blomberg M. Maternal body mass index and duration of labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(1):49–53.

Dolea C, AbouZahr C. Global burden of obstructed labour in the year 2000. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Denison F, Price J, Graham C, Wild S, Liston W. Maternal obesity, length of gestation, risk of postdates pregnancy and spontaneous onset of labour at term. BJOG. 2008;115(6):720–5.

Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell C, Hunter A, Holmes V. The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004–2011. BJOG. 2013;120(8):932–9.

Dodd JM, Grivell RM, Nguyen AM, Chan A, Robinson JS. Maternal and perinatal health outcomes by body mass index category. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(2):136–40.

Chen Z, Du J, Shao L, Zheng L, Wu M, Ai M, Zhang Y. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy outcomes in China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109(1):41–4.

Cresswell JA, Campbell OMR, D-Silva M, Filippi V. Effect of maternal obesity on neonatal death in sub-Saharan Africa: multivarible analysis of 27 national datasets. Lancet. 2012;380:1325–30.

Pullum TW. An assessment of age and date reporting in the DHS Surveys 1985–2003. 2006.

Acknowledgements

The dataset used in this study was obtained from MEASURE DHS Archive. The authors thank MEASURE DHS for granting permission to access the data set. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Population Science and Human Resource Development, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh where this study was conducted.

Funding

There is no funding source for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The DHS Program [24],but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of The DHS Program.

Authors’ contributions

Khan MN had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Khan MN and Rahman MM conceptualized the analysis plan for this study. Khan MN drafted the paper and performed the statistical analysis together with Rahman MM. Khan MN interpreted the results consulting with Rahman MM. Rhaman MM, Rahman MM and Shariff AA critically reviewed all versions of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial and non-financial competing interest related to this paper.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of ICF International reviewed and approved The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program (DHS-6 and DHS-7). The 2014 and 2011 Bangladesh DHS is categorized under that approval. This organization follows international ethical standards to ensure confidentiality, anonymity, and informed consent. The standard process of obtaining written informed consent was followed in the case of all participants in this research. All efforts were made to conduct the interviews in a private location and to maintain confidentiality of the information collected. It was also made clear to the informants that they had full right to refuse to respond any questions or to terminate interviews at any time if and when they want for any reason.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Percentage distribution of the respondents by some selected socio economic characteristics and BMI. Table S2. STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies. (DOC 134 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Rahman, M., Shariff, A.A. et al. Maternal undernutrition and excessive body weight and risk of birth and health outcomes. Arch Public Health 75, 12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0181-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0181-0