Abstract

In this work, we introduce the concept of a cyclic compatible contraction and prove related fixed point theorems in the generating space of a b-quasi-metric family.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and preliminaries

Throughout this paper \(\mathbb{R}\), \(\mathbb{R}^{+}\), and \(\mathbb{N}\) represent the set of real numbers, the set of positive real numbers, and the set of positive integers, respectively.

In 1922, Banach introduced the contraction mapping theorem which is famously known as the Banach contraction principle. It is also known that Banach’s contraction principle is one of the pivotal result of metric fixed point theory.

Banach contraction principle [1]: If \((X,d)\) is a complete metric space and \(T:X\rightarrow X\) is a self-mapping such that

for all \(x,y\in X\), where \(0\leq\alpha<1\), then T has a unique fixed point.

This theorem ensures the existence and uniqueness of fixed points of certain self-maps of metric spaces, and it gives a useful constructive method to find those fixed points.

The traditional Banach contraction principle has been extended and generalized in wide directions.

Now, we list some of the important generalizations of the Banach contraction principle in the 19th century:

-

In 1968, Kannan fixed point theorem [2]: If \((X,d)\) is a complete metric space and \(T:X\rightarrow X\) is a self-mapping such that

$$d(Tx,Ty)\leq\beta\bigl[d(x,Tx)+d(y,Ty)\bigr], $$for all \(x,y\in X\), where \(0\leq\beta<\frac{1}{2}\), then T has a unique fixed point.

-

In 1971, Reich fixed point theorem [3]: If \((X,d)\) is a complete metric space and \(T:X\rightarrow X\) is a self-mapping such that

$$d(Tx,Ty)\leq\alpha d(x,y)+\beta d(x,Tx)+\gamma d(y,Ty), $$for all \(x,y\in X\), where α, β, γ are non-negative constants with \(\alpha+\beta+\gamma<1\), then T has a unique fixed point.

-

In 1971, Ciric fixed point theorem [4]: If \((X,d)\) is a complete metric space and \(T:X\rightarrow X\) is a self-mapping such that

$$d(Tx,Ty)\leq\alpha d(x,y)+\beta d(x,Tx)+\gamma d(y,Ty)+\delta \bigl[d(x,Ty)+d(y,Tx)\bigr], $$for all \(x,y\in X\), where α, β, γ, δ are non-negative constants with \(\alpha+\beta+\gamma+2\delta<1\), then T has a unique fixed point.

The above named fixed point theorems are undoubtedly the most valuable theorems in nonlinear phenomena. Many fixed point theorems concerning the above named theorems and their generalizations have been given by several authors (for example, see [5–12]).

The Banach contraction principle appears everywhere in mathematics: Analysis, geometry, statistics, graph theory, and logic programming are some of the fields in which the Banach contraction principle and/or generalizations play an important role. In the literature, we can say that the elegant generalizations below are the standard generalizations of the Banach contraction principle in 20th century.

In 2003, Kirk et al., generalized the Banach contraction principle by using cyclic map and proved below fixed point theorem.

Theorem 1.1

[13]

Let A and B be non-empty closed subsets of a complete metric space \((X,d)\) and \(T:A\cup B \rightarrow A\cup B\) be a cyclic map (T is called a cyclic map iff \(T(A)\subseteq B\) and \(T(B)\subseteq A\)). If there exists \(k\in(0,1)\) such that

for all \(x\in A\) and \(y\in B\), then T has a unique fixed point z. Moreover, \(z\in A\cap B\).

In 2012, Wardowski [14] introduced the F-contraction and generalized the Banach contraction principle in a new way.

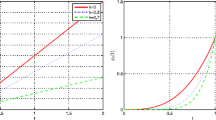

F-contraction: Let \(F:\mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be a mapping satisfying:

-

(F1)

F is strictly increasing, i.e. for all \(\alpha ,\beta\in \mathbb{R}^{+}\) such that \(\alpha<\beta\), \(F(\alpha)< F(\beta)\);

-

(F2)

for each sequence \(\{\alpha_{n}\}_{n\in\mathbb{N}}\) of positive numbers \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}\alpha_{n}=0\) iff \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}F(\alpha_{n})= -\infty\);

-

(F3)

there exists \(k\in(0,1)\) such that \(\lim_{\alpha \rightarrow0^{+}}\alpha^{k}F(\alpha)=0\).

A mapping \(T:X\rightarrow X\) is said to be an F-contraction if there exists \(\tau>0\) such that for all \(x,y\in X\), \(d(Tx,Ty)>0 \Rightarrow \tau+F(d(Tx,Ty))\leq F(d(x,y))\).

Theorem 1.2

[14]

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete metric space and let \(T:X\rightarrow X\) be an F-contraction, then T has a unique fixed point \(x^{\ast}\in X\) and for every \(x_{0}\in X\) a sequence \(\{T^{n}x_{0}\}_{n\in\mathbb{N}}\) is convergent to \(x^{\ast}\).

Very recently, Piri and Kumam [15] extended the result of Wardowski [14] by replacing (F3) in the F-contraction with the following one:

- (F3′):

-

F is continuous on \((0,\infty)\).

Let \(\mathfrak{F}\) denote the family of all functions \(F : \mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) which satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F3′).

The authors of [15] generalized the standard F-contraction and proved a fixed point result with the above new set-up.

The concept of weakly compatible maps was introduced by Jungck [16].

Definition 1.3

[16]

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete metric space and \(T,S\) be two mappings. Then T and S are said to be weakly compatible if they commute at their coincidence point x, that is, \(Tx = Sx\) implies \(TSx = STx\).

The above concept is used to prove existence theorems in common fixed point theory. However, the study of common fixed points of weakly compatible maps is very impressive. In the literature one can find some interesting papers concerning cyclic contraction, F-contraction and weakly compatible mapping (see for example [17–26]).

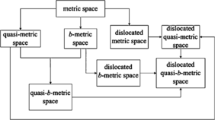

On the other hand, the standard metric space has been generalized in different ways: see for example:

-

the b-metric space by Bakhtin [27],

-

the generalized metric space by Branciari [28],

-

the multiplicative metric space by Bashirov et al. [29],

-

the dislocated symmetric space by Sarma et al. [30],

-

the quasi-symmetric space by Kumari et al. [31],

-

the dislocated uniform space by Kumari et al. [32].

Apart from the above, we collected various definitions of such spaces. For more details, the reader can refer to [18].

Definition 1.4

[18]

Let X be a non-empty set and \(\{d_{\alpha}:\alpha\in(0,1]\}\) a family of mappings \(d_{\alpha}\) of \(X\times X\) into \(\mathbb{R}^{+}\). Consider the following conditions for any \(x,y,z\in X\) and \(s\geq1\):

- (d1):

-

the family of self distances are zero: \(d_{\alpha}(x,x)=0\);

- (d2):

-

the family of distances are symmetric: \(d_{\alpha}(x,y)=d_{\alpha}(y,x)\);

- (d3):

-

the family of positive distances between distinct points: \(d_{\alpha}(x,y)=d_{\alpha}(y,x)=0\) implies \(x=y\);

- (d4):

-

for any \(\alpha\in(0,1]\) there exists \(\beta\in(0,\alpha]\) such that \(d_{\alpha}(x,z)\leq s[d_{\beta}(x,y)+d_{\beta}(y,z)]\);

- (d5):

-

for any \(x,y\in X\), \(d_{\alpha}(x,y)\) is non-increasing and left continuous in α.

\(d_{\alpha}\) is called:

-

(i)

the generating space of the b-quasi-metric family (shortly, the \(G_{bq}\)-family) if \(d_{\alpha}\) satisfies (d1) through (d5);

-

(ii)

the generating space of the b-dislocated metric family (shortly, the \(G_{bd}\)-family) if \(d_{\alpha}\) satisfies (d2) through (d5);

-

(iii)

the generating space of the b-dislocated-quasi-metric family (shortly, the \(G_{bdq}\)-family) if \(d_{\alpha}\) satisfies (d3) through (d5).

Now we give some basic definitions of the generating space of a b-quasi-metric family.

Definition 1.5

[18]

-

1.

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a \(G_{bq}\)-family and let \(\{x_{n}\}\) be a sequence in X. We say that \(\{x_{n}\}\) \(G_{bq}\)-converges to x in \((X,d_{\alpha})\) if \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}d_{\alpha}(x_{n},x)=0\) for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\).

In this case we write \(x_{n}\rightarrow x\).

-

2.

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a \(G_{bq}\)-family and let \(A\subseteq X\), \(x\in X\). We say that x is a \(G_{bq}\)-limit point of A if there exists a sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) in \(A-\{x\}\) such that \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}x_{n}=x\).

-

3.

A sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) in a \(G_{bq}\)-family is called a \(G_{bq}\)-Cauchy sequence if given \(\epsilon>0\), there exists \(n_{0}\in\mathbb{N}\) such that for all \(n,m\geq n_{0}\), we have \(d_{\alpha}(x_{n},x_{m})<\epsilon\) or \(\lim_{ n,m\rightarrow \infty} d_{\alpha}(x_{n},x_{m})=0 \) for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\).

-

4.

A \(G_{bq}\)-family \((X,d_{\alpha})\) is called complete if every \(G_{bq}\)-Cauchy sequence in X is \(G_{bq}\)-Convergent.

Remark 1.6

Every \(G_{bq}\)-convergent sequence in a \(G_{bq}\)-family is \(G_{bq}\)-Cauchy.

A similar argument can be found in [33–36].

If we take \(s=1\) then generating space of b-quasi-metric family becomes generating space of quasi-metric family as defined by Chang et al. [36].

Example 1.7

Let \((X, d)\) be a metric space. If we put \(d_{\alpha}\) instead of d for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\) and \(x,y\in X\), then \((X, d_{\alpha})\) is a generating space of quasi-metric family.

In [34], the author proved that each generating space of quasi-metric family generates a topology \(\Im_{d_{\alpha}}\) whose base is the family of open balls. The ‘\(G_{bq}\)-family’ will play a very predominant role in fixed point theory because the class of \(G_{bq}\)-family is larger than the generating space of quasi-metric family.

Motivated by the above facts, in this paper, we introduce the concept of a cyclic compatible contraction and prove related fixed point theorems in the generating space of a b-quasi-metric family.

2 Main results

Definition 2.1

Let A and B be non-empty subsets of the generating space of a b-quasi-metric family \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose S and T are cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that \(SX\subset TX\) and for some \(x\in A\) there exists a \(\gamma\in(0,1)\) in such way that

for all \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and \(y\in A\). Then S, T are called cyclic compatible contractions.

Theorem 2.2

Let A and B be non-empty closed subsets of a complete \(G_{bq}\)-family \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose:

-

1.

\(S,T:A\cup B \rightarrow A\cup B\) be a cyclic compatible contraction.

-

2.

TX is a closed subset of X.

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Proof

Let \(x=x_{0}\in A\) be an arbitrary point. Since \(S(X)\subset T(X)\), we may choose \(x_{1}\in X\) such that

Hence we can define the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) in X by \(Sx_{n}=Tx_{n+1}\) for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\cup\{0\}\). Then \(\{x_{2n}\}\in A\) and \(\{x_{2n-1}\}\in B\).

We have

Similarly,

Inductively, for each \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), we get

Now we claim \(\{x_{n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence. According to the definition of a \(G_{bq}\)-family, we have

Since \(0<\gamma<1\), letting \(n\rightarrow\infty\), we get \(d_{\alpha}(x_{n},x_{m})\rightarrow0\) for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\). Therefore \(\{x_{n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence in X. Since X is complete, there is a sequence \(\{T^{2n}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{T^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) is in B such that both converge to some η in X. Since A and B are closed in X, \(\eta\in A\cap B\).

Since TX is closed, there exists u in X such that

From the above argument and (2), there exist sequences \(\{S^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{S^{2n-2}x_{0}\}\) in B such that both converge to η.

Consider \(d_{\alpha}(S^{2n-1}x_{0},Su)\leq\gamma d_{\alpha}(S^{2n-2}x_{0},Tu)\).

By letting \(n\rightarrow\infty\), \(d_{\alpha}(\eta,Su)\leq\gamma d_{\alpha}(\eta,Tu)\).

This yields \(d_{\alpha}(\eta,Su)=0\). Thus

From (2) and (3), it follows that \(Tu=Su=\eta\). Thus η is a point of coincidence for S and T.

From the weak compatibility, we get

Now our aim is to prove \(T\eta=\eta\).

Consider

This yields \((1-\gamma)d_{\alpha}(\eta,T\eta)\leq0\).

Therefore \(d_{\alpha}(\eta,T\eta)=0\).

Thus \(\eta=T\eta\).

From (4), we get \(S\eta=T\eta=\eta\).

Hence η is a common fixed point of S and T.

To prove uniqueness, let us suppose that \(\eta_{1}\) and \(\eta_{2}\) are two fixed points of S and T.

Then \(S\eta_{1}=T\eta_{1}=\eta_{1}\) and \(S\eta_{2}=T\eta_{2}=\eta_{2}\). Consider

Thus \((1-\gamma)d_{\alpha}(\eta_{1},\eta_{2})\leq0\).

Hence \(\eta_{1}=\eta_{2}\), since \(0<\gamma<1\).

If we put \(s=1\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in the generating space of a quasi-metric family. □

Corollary 2.3

Let A and B be non-empty closed subsets of a complete \(G_{q}\)-family \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose:

-

1.

\(S,T:A\cup B \rightarrow A\cup B\) are cyclic compatible contractions.

-

2.

TX is a closed subset of X.

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

If we write d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in a complete b-metric space.

Corollary 2.4

Let A and B be non-empty closed subsets of a complete b-metric space \((X,d)\). Suppose:

-

1.

\(S,T:A\cup B \rightarrow A\cup B\) are cyclic compatible contractions.

-

2.

TX is a closed subset of X.

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Example 2.5

Let \(X=[0,20]\) and \(A=B=(0,20]\) and define \(d:X\times X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{+}\) by \(d(x,y)=(x-y)^{2}\). Then \((X,d)\) is a b-metric space with \(s=2\) which is not a metric space as \(d(0,3)\nleq d(0,1)+d(1,3)\). Define \(S,T:A\cup B\rightarrow A\cup B\) as follows:

and

Fix any \(x\in[4,20]\). By taking \(\gamma=\frac{1}{3}\), we have \(Sx=S^{2}x=S^{3}x=\cdots=S^{n}x=0\) for all n and for every \(y\in(4,20]\), we have

and

Thus the cyclic compatible contraction condition \((S^{2n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma d(S^{2n-1}x,Ty)\), for each \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and for each \(y\in[0,20]\), is satisfied for \(\gamma=\frac{1}{3}\). Thus by Corollary 2.4, S and T have the unique common fixed point. In fact, ‘0’ is the unique common fixed point for S and T.

If we put \(s=1\) and d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in a complete metric space.

Corollary 2.6

Let A and B be non-empty closed subsets of a complete metric space \((X,d)\). Suppose:

-

1.

\(S,T:A\cup B \rightarrow A\cup B\) are cyclic compatible contractions.

-

2.

TX is a closed subset of X.

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Example 2.7

Let \(X=[0,1]=A=B\) and define \(d:X\times X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{+}\) by \(d(x,y)=|x-y|\). Then \((X,d)\) is a metric space. Define \(S,T:A\cup B\rightarrow A\cup B\) as follows:

and \(Sx=0.3\) if \(0\leq x\leq1\). Clearly \(S(X)\subset T(X)\).

Fix any \(x\in[0,1]\). By taking \(\gamma=\frac{1}{2}\), we have \(Sx=S^{2}x=S^{3}x=\cdots=S^{n}x=0.3\) for all n and for every \(y\in[0,1]\), we have

and \(Sy=0.3\) if \(0\leq y\leq1\).

\(d(S^{2n}x,Sy)=d(0.3,0.3)=0\) if \(0\leq y\leq1\) and

Hence the cyclic compatible contraction condition \(d(S^{2n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma d(S^{2n-1}x,Ty)\), for each \(n\in \mathbb{N}\) and for each \(y\in[0,1]\), is satisfied for \(\gamma=\frac{1}{2}\). Thus by Corollary 2.6, S and T have the unique common fixed point. In fact ‘0.3’ is the unique common fixed point for S and T.

Theorem 2.8

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a complete \(g_{bq}\)-family and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose S and T are cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that the range of T contains the range of S. TX is closed in subsets of X. For some \(x\in A\) and \(\gamma\in(0,\frac{1}{s})\), there exists

such that \(d_{\alpha}(S^{n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma\omega\) for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\) and \(y\in A\). Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cup B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Proof

Let \(x_{0}=x\in X\) be fixed. As \(S(X)\subset T(X)\), we may choose \(x_{1}\in X\) such that

Hence we can define the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) in X by \(Sx_{n}=Tx_{n+1}=T^{n+1}x_{0}=x_{n+1}\) for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\cup\{0\}\).

Consider

where

Therefore,

Similarly,

where

Then, from (9), we get

Hence for each \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), by using induction, we get

for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\).

Now we prove that \(\{x_{n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence.

From the definition of the generating space of a b-quasi-metric family, we get

Letting \(n\rightarrow\infty\), since \(s\gamma<1\), \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}d_{\alpha}(x_{n},x_{m})\rightarrow 0\) for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\), which shows that \(\{x_{n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence in X. Since X is complete, there is a sequence \(\{T^{2n}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{T^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) is in B such that both converge to some η in X. This implies \(\eta\in A\cap B\), as A and B are closed subsets of X.

Since TX is closed, there exists μ in X such that

As \(SX\subset TX\), and from the above, we get sequences \(\{S^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{S^{2n-2}x_{0}\}\) in B such that both converge to η.

Consider

\(d_{\alpha}(S\mu,T\mu)= 0\).

This yields

From (11) and (12), \(S\mu=T\mu=\eta\).

Thus η is a point of coincidence of S and T. From the weak compatibility, we have

Now we claim that η is a common fixed point of S and T,

First we claim that \(S\eta=\eta\). Consider,

This implies

Since \(1-\gamma\geq0\), \(d_{\alpha}(S\eta,\eta)=0\).

Thus

From (13) and (14), \(S\eta=T\eta=\eta\).

In order to prove uniqueness, suppose that \(\eta_{1}\) and \(\eta_{2}\) are two common fixed points of S and T.

That is, \(S\eta_{1}=T\eta_{1}=\eta_{1}\) and \(S\eta_{2}=T\eta_{2}=\eta_{2}\). Then consider

This implies \((1-\gamma)d_{\alpha}(\eta_{1},\eta_{2})=0\). Hence \(\eta_{1}=\eta_{2}\). □

If we put \(s=1\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in the generating space of a quasi-metric family.

Corollary 2.9

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a complete \(g_{q}\)-family and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose S and T are cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that the range of T contains the range of S. TX is closed in subsets of X. For some \(x\in A\) and \(\gamma\in(0,1)\), there exists

such that \(d_{\alpha}(S^{n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma\omega\) for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\) and \(y\in A\). Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cup B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

If we write d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in a complete b-metric space.

Corollary 2.10

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete b-metric space and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d)\). Suppose S and T be cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that the range of T contains the range of S. TX is closed in subsets of X. For some \(x\in A\) and \(\gamma\in(0,\frac{1}{s})\), there exists

such that \(d(S^{n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma\omega\) for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and \(y\in A\). Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cup B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

If we put \(s=1\) and d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in a complete metric space.

Corollary 2.11

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete metric space and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d)\). Suppose S and T are cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that the range of T contains the range of S. TX is closed in subsets of X. For some \(x\in A\) and \(\gamma\in(0,1)\), there exists

such that \(d(S^{n}x,Sy)\leq\gamma\omega\) for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and \(y\in A\). Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cup B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible, then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Theorem 2.12

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a complete \(G_{bq}\)-family and A, B are non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose S and T are cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that \(SX\subset TX\). Assume \(\mathcal{F}:\mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is a mapping satisfying the following conditions:

- (F1):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is strictly increasing,

- (F2):

-

\(\operatorname{Inf}\mathcal{F}=-\infty\),

- (F3):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is continuous on \((0,\infty)\),

- (F4):

-

for some \(x\in A\) there exists \(\tau>0\) such that

$$d_{\alpha}(Tx,Ty)>0\quad\Rightarrow\quad\tau+\mathcal{F}\bigl(d_{\alpha } \bigl(S^{n}x,Sy\bigr)\bigr)\leq\mathcal{F}\bigl(d_{\alpha} \bigl(S^{n-1}x,Ty\bigr)\bigr), $$for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), \(y\in A\).

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

Proof

Fix \(x\in A\). Since \(SX\subset TX\), we may choose \(x_{0}=x\in X\) such that \(Sx_{0}=Tx_{1}\).

Hence define the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) in X by \(Sx_{n}=Tx_{n+1}=T^{n+1}x_{0}=x_{n+1}\) for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\cup\{0\}\).

If \(x_{0}=Tx_{0}\), the proof is complete. So we assume that \(x_{0}\neq Tx_{0}\). This yields \(d_{\alpha}(x_{0},Tx_{0})>0\).

Hence from (F4), we get

Similarly,

Inductively, for each \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), we get

By applying \(n\rightarrow\infty\), we get

From (F2), we have

Now we prove that \(\{x_{n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence. Suppose, to the contrary, that \(\{x_{n}\}\) is not a Cauchy sequence. Then there exist \(\delta>0\) and sequences \(\{\eta(n)\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) and \(\{\psi(n)\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) of natural numbers such that n is the smaller index for which \(\eta(n)>\psi(n)>n\), and

for all \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and \(\alpha\in(0,1]\).

By using the definition of a \(G_{bq}\)-family and (19), we get

By taking \(n\rightarrow\infty\) in the above inequality and using (18), we obtain

From the sandwich theorem and (21), we get

From (18), there exists \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) such that

for all \(n\in\mathbb{N}\) and \(\alpha\in(0,1]\).

Now, we claim that \(d_{\alpha}(Tx_{\eta(n)},Tx_{\psi(n)})>0\).

Arguing by contradiction, there exists \(m\geq n\) such that

This contradicts the argument that

Thus

From the assumption of the theorem, we have

From the hypothesis of the theorem, (22), and (26), we get \(\tau+\mathcal{F}(\delta)<\mathcal{F}(\delta)\).

This is a contradiction. Hence \(\{x_{n}\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) is a Cauchy sequence. By completeness of \((X,d_{\alpha})\), there is a sequence \(\{T^{2n}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{T^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) in B such that both converge to some u in X for all \(\alpha\in(0,1]\). Since A and B are closed subsets of X, \(u\in A\cup B\).

As TX is closed, there exists z in X such that

Since \(Sx_{n}=Tx_{n+1}\) and by using the above argument, there exist sequences \(\{S^{2n-1}x_{0}\}\) in A and \(\{S^{2n-2}x_{0}\}\) in B such that both converge to u.

This means

Consider \(\mathcal{F}(d_{\alpha}(S^{2n-1}x_{0},Sz))\leq \mathcal{F}(d_{\alpha}(S^{2n-2}x_{0},Tz))-\tau\).

Letting \(n\rightarrow\infty\) and from (28), the hypothesis of the theorem, we get

Hence again from the hypothesis of the theorem, we obtain

This implies \(d_{\alpha}(u,Sz)=0\). Thus,

From (27) and (29), it follows that \(Tz=Sz=u\). Thus u is a point of coincidence for S and T.

From the weakly compatibility definition, we get

Now we claim that \(Tu=u\).

From (F1) and (F4), T is continuous. Therefore,

which yields

From (30) and (31), we get \(Su=Tu=u\).

Hence u is a common fixed point of S and T.

Now we prove the uniqueness of the common fixed point.

Let us assume that u and v are two common fixed points of S and T such that \(Su=Tu=u\) and \(Sv=Tv=v\) but \(u\neq v\).

Hence \(d_{\alpha}(u,v)>0\). From the assumption of the theorem, we get

This is a contradiction.

Hence \(u=v\). This completes the proof of the theorem. □

If we put \(s=1\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in the generating space of a quasi-metric family.

Corollary 2.13

Let \((X,d_{\alpha})\) be a complete \(G_{q}\)-family and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d_{\alpha})\). Suppose S and T be cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that \(SX\subset TX\). Assume \(\mathcal{F}:\mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is a mapping satisfying following conditions:

- (F1):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is strictly increasing,

- (F2):

-

\(\operatorname{Inf}\mathcal{F}=-\infty\),

- (F3):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is continuous on \((0,\infty)\),

- (F4):

-

for some \(x\in A\) there exists \(\tau>0\) such that

$$d_{\alpha}(Tx,Ty)>0\quad\Rightarrow\quad\tau+\mathcal{F}\bigl(d_{\alpha } \bigl(S^{n}x,Sy\bigr)\bigr)\leq\mathcal{F}\bigl(d_{\alpha} \bigl(S^{n-1}x,Ty\bigr)\bigr), $$for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), \(y\in A\).

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

If we write d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in complete b-metric space.

Corollary 2.14

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete b-metric space and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d)\). Suppose S and T be cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that \(SX\subset TX\). Assume \(\mathcal{F}:\mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is a mapping satisfying following conditions:

- (F1):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is strictly increasing,

- (F2):

-

\(\operatorname{Inf}\mathcal{F}=-\infty\),

- (F3):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is continuous on \((0,\infty)\),

- (F4):

-

for some \(x\in A\) there exists \(\tau>0\) such that

$$d(Tx,Ty)>0\quad\Rightarrow\quad\tau+\mathcal{F}\bigl(d\bigl(S^{n}x,Sy\bigr) \bigr)\leq\mathcal {F}\bigl(d\bigl(S^{n-1}x,Ty\bigr)\bigr), $$for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), \(y\in A\).

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

If we put \(s=1\) and d instead of \(d_{\alpha}\) in the above theorem, we obtain the following corollary in a complete metric space.

Corollary 2.15

Let \((X,d)\) be a complete metric space and A, B be non-empty closed subsets of \((X,d)\). Suppose S and T be cyclic mappings from \(A\cup B\) to \(A\cup B\) such that \(SX\subset TX\). If \(\mathcal{F}:\mathbb{R}^{+}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is a mapping satisfying the following conditions:

- (F1):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is strictly increasing,

- (F2):

-

\(\operatorname{Inf}\mathcal{F}=-\infty\),

- (F3):

-

\(\mathcal{F}\) is continuous on \((0,\infty)\),

- (F4):

-

for some \(x\in A\) there exists \(\tau>0\) such that

$$d(Tx,Ty)>0\quad\Rightarrow\quad\tau+\mathcal{F}\bigl(d\bigl(S^{n}x,Sy\bigr) \bigr)\leq\mathcal {F}\bigl(d\bigl(S^{n-1}x,Ty\bigr)\bigr), $$for \(n\in\mathbb{N}\), \(y\in A\).

Then S and T have a point of coincidence in \(A\cap B\). Moreover, if S and T are weakly compatible then S and T have a unique common fixed point in \(A\cap B\).

References

Banach, S: Sur les opérations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur applications aux équations intégrales. Fundam. Math. 3, 133-181 (1922)

Kannan, R: Some results on fixed points. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 60, 71-76 (1968)

Reich, S: Some remarks concerning contraction mappings. Can. Math. Bull. 14, 121-124 (1971)

Ciric, LB: Generalized contractions and fixed-point theorems. Publ. Inst. Math. (Belgr.) 12(26), 19-26 (1971)

Kannan, R: Some results on fixed points. II. Am. Math. Mon. 76, 405-408 (1969)

Chatterjea, SK: Fixed-point theorems. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 25, 727-730 (1972)

Hardy, GE, Rogers, TD: A generalization of a fixed point theorem of Reich. Can. Math. Bull. 16, 201-206 (1973)

Meir, A, Keeler, E: A theorem on contraction mappings. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 28, 326-329 (1969)

Subrahmanyam, PV: Completeness and fixed-points. Monatshefte Math. 80, 325-330 (1975)

Edelstein, M: An extension of Banach’s contraction principle. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 12, 7-10 (1961)

Ciric, LB: A generalization of Banach’s contraction principle. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 45, 267-273 (1974)

Taskovic, MR: A generalization of Banach’s contraction principle. Publ. Inst. Math. 37, 179-191 (1978)

Kirk, WA, Srinavasan, PS, Veeramani, P: Fixed points for mapping satisfying cyclical contractive conditions. Fixed Point Theory 4, 79-89 (2003)

Wardowski, D: Fixed point theory of a new type of contractive mappings in complete metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2012, Article ID 94 (2012)

Piri, H, Kumam, P: Some fixed point theorems concerning F-contraction in complete metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2014, Article ID 210 (2014). doi:10.1186/1687-1812-2014-210

Jungck, G: Common fixed points for noncontinuous non-self maps on nonmetric spaces. Far East J. Math. Sci. 4, 199-215 (1996)

Zoto, K, Kumari, PS, Hoxha, E: Some fixed point theorems and cyclic contractions in dislocated and dislocated quasi-metric spaces. Am. J. Numer. Anal. 2(3), 79-84 (2014)

Kumari, PS, Panthi, D: Cyclic contractions and fixed point theorems on various generating spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2015, Article ID 153 (2015)

Kumari, PS, Zoto, K, Panthi, D: d-Neighborhood system and generalized F-contraction in dislocated metric space. SpringerPlus 4(1), 1-10 (2015)

Shukla, S, Radenovic, S: Some common fixed point theorems for F-contraction type mappings in 0-complete partial metric spaces. J. Math. 2013, Article ID 878730 (2013)

Kumari, PS, et al.: Common fixed point theorems on weakly compatible maps on dislocated metric spaces. Math. Sci. 6, 71 (2012)

Panthi, D, Jha, K: A common fixed point of weakly compatible mappings in dislocated metric space. Kathmandu Univ. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 8(2), 25-30 (2013). doi:10.3126/kuset.v8i2.7321

Kumari, PS, Kumar, VV, Sarma, R: New version for Hardy and Rogers type mapping in dislocated metric space. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 1(4), 609-617 (2012)

Rao, JM, Kumari, PS, Zoto, K: Some fixed point theorems in symmetric spaces. Inf. Sci. Comput. 2013(2), Article ID ISC220913 (2013)

Panthi, D, Jha, K, Jha, PK, Kumari, PS: A common fixed point theorem for two pairs of mappings in dislocated metric space. Am. J. Comput. Math. 5, 106-112 (2015)

Di Bari, C, Vetro, C: Common fixed point for weakly compatible maps satisfying a general contractive condition. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2008, Article ID 891375 (2008)

Bakhtin, IA: The contraction mapping principle in quasi-metric spaces. In: Functional Analysis, vol. 30. Ul’yanovsk. Gos. Ped. Inst., Ul’yanovsk (1989)

Branciari, A: A fixed point theorem of Banach-Caccioppoli type on a class of generalized metric spaces. Publ. Math. (Debr.) 57(1-2), 31-37 (2000)

Bashirov, AE, Kurplnara, EM, Ozyapici, A: Multiplicative calculus and its applications. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 337, 36-48 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2007.03.081

Sarma, IR, Rao, JM, Kumari, PS, Panthi, D: Convergence axioms on dislocated symmetric spaces. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, Article ID 745031 (2014). doi:10.1155/2014/7450317

Kumari, PS, Ramana, CV, Zoto, K: On quasi-symmetric space. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 7(10), 1583-1587 (2014)

Kumari, PS, Sarma, IR, Rao, JM: Metrization theorem for a weaker class of uniformities. Afr. Math. (2015). doi:10.1007/s13370-015-0369-9

Sarma, IR, Kumari, PS: On dislocated metric spaces. Int. J. Math. Arch. 3(1), 7-27 (2012)

Fan, JX: On the generalizations of Ekeland’s variational principle and Caristi’s fixed point theorem. In: The 6th National Conf. on the Fixed Point Theory, Variational Inequalities and Probabilistic Metric Spaces Theory, Qingdao, China (1993)

Kumari, PS: On dislocated quasi metrics. J. Adv. Stud. Topol. 3(2), 66-74 (2012)

Chang, SS, Cho, YJ, Lee, BS, Jung, JS, Kang, SM: Coincidence point theorems and minimization theorems in fuzzy metric spaces. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 88, 119-127 (1997)

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to express her sincere gratitude to Mr. Anand Prabhakar for his invaluable support and motivation. The authors would like to express their thanks to the referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumari, P.S., Panthi, D. Cyclic compatible contraction and related fixed point theorems. Fixed Point Theory Appl 2016, 28 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-016-0521-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-016-0521-8