Abstract

The paper deals with the here defined dislocated strong quasi-metric (if \(p(y,x)= 0\), then \(x=y\); \(0 \leq p(z,x) \leq p(z,y) + p(y,x)\)) and with the well-known notion of the dislocated metric (in addition, \(p(y,x)= p(x,y)\)). In particular, the partial metric is a kind of dislocated metric. Our basic results on general contractions (also for cyclic mappings) and results of variational type can be treated as a starting point for further development.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

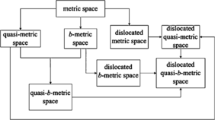

Recent years have witnessed the appearance of many papers devoted to fixed point theorems for partial metric spaces. The aim of the present paper is to show that the dislocated (strong quasi-)metric as presented here (Definition 2.1) has a great potential. Each partial metric is a dislocated metric and examples preceding Definition 2.4 show that the dislocated metric is more general. The paper is divided into three sections.

In Section 2 the definitions of a dislocated (strong quasi-)metric and of a partial metric are presented. This section contains some examples and a comparison between the two notions. Also some additional ideas (0-completeness, Kerp) are included.

Section 3 is devoted to fixed point theorems for general contractions. The simplest requirement is condition (3.1): \(p(f(y),f(x)) \leq \varphi (p(y,x))\), for all \(x,y \in X\), where p is a dislocated metric on X, \(f : X \rightarrow X\) is a mapping, and the comparison function \(\varphi : [0,\infty) \rightarrow[0,\infty)\) belongs to a wide class of mappings defined in [1] and here. The main classical results are Theorem 3.3 (a direct extension of the celebrated theorems of Matkowski [2], Theorem 1.2, and of Boyd-Wong [3], Theorem 1), and a more general Theorem 3.5. The most sophisticated ones are the theorems for cyclic mappings (see Definition 3.6): Theorem 3.9, and a result of a new type, Theorem 3.10, which is proved with the use of cross mappings defined in [4]. Our theorems extend also some general results of Karapinar and Salimi [5], Theorems 1.8, 1.9.

Section 4 (p is a dislocated strong quasi-metric) contains theorems obtained with order reasoning for a transitive relation defined by \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi(y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\) where \(\psi: X \rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is a mapping. The results of variational type involve the existence and properties of the smallest element in a maximal chain. Typical are Theorems 4.1 and 4.2, and an extension of the Ekeland principle (Theorem 4.5). The fixed point results are Theorem 4.3 and Theorem 4.4 (an extension of the celebrated theorems of Caristi and Takahashi).

2 Dislocated metric and dislocated strong quasi-metric

The notion of dislocated metric was introduced by Hitzler and Seda in [6].

Definition 2.1

Let X be a nonempty set, and \(p : X \times X \rightarrow[0,\infty)\) a mapping satisfying

Then p is called a dislocated strong quasi-metric (briefly a dsq-metric), and \((X,p)\) is called a dislocated strong quasi-metric space (briefly a dsq-metric space). The kernel of p is the set

If, in addition,

holds, then p is called a dislocated metric (briefly a d-metric), and \((X,p)\) is called a dislocated metric space (briefly a d-metric space).

In the previous version of the present paper (entitled ‘Near (quasi-)metric and fixed point theorems’) dislocated metric was called near metric because the author was not aware of Hitzler’s definition, and a dislocated strong quasi-metric was called a near quasi-metric.

The nonalphabetical order of \(x,y,z\) in conditions (2.1), (2.2), (2.3) is better suited to the results of Section 4 (\(y = f(x) \preccurlyeq x\) corresponds with \(\psi(y) \leq\psi(x)\)).

The topology of a d-metric (or dsq-metric) space \((X,p)\) is generated by balls \(B(x,r) = \{y \in X : p(x,y)< r\}\). Clearly, \(x \in B(x,r) \) does not necessarily hold, but the family of all balls generates the respective smallest topology for \(X = \bigcup\{ B(x,r) : x \in X, r > 0\}\) [7], Theorem 12, p.47. If \(Z = \operatorname {Ker}p\) is nonempty, then \((Z,p_{|Z \times Z})\) is a metric (or quasi-metric) subspace of \((X,p)\).

Recently, Amini-Harandi has defined metric-like mapping σ (identic with the idea of d-metric p) and metric-like space \((X,\sigma)\) [8], Definition 2.1. The topology of his space generated by σ-balls \(B_{\sigma}(x,\epsilon) = \{y \in X : |\sigma(x,y) - \sigma(x,x)| < \epsilon\}\) usually differs from the topology for a d-metric space.

It should be noted that also Karapinar and Salimi [5] follow the ideas of Amini-Harandi, which are better suited to partial metric spaces (see Definition 2.4).

For the d-metric p the following condition is satisfied:

Indeed, from \(0 \leq p(y,x)\leq p(y,x_{n}) + p(x,x_{n})\) it follows that \(p(y,x)= 0\), \(x = y\) (see (2.1)), and \(p(x,x)= 0\) means that \(x \in \operatorname {Ker}p\).

Proposition 2.2

Let \((X,p)\) be a d-metric (or dsq-metric) space. Then \(p(\cdot,y)\) is lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp, \(y \in X\).

Proof

Let \((x_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) be such that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}p(x,x_{n})= 0\). Then the inequality \(p(x,y) \leq \liminf_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x_{n},y)\) is a consequence of \(p(x,y)\leq p(x,x_{n})+ p(x_{n},y)\). □

Definition 2.3

A d-metric (or dsq-metric) space \((X,p)\) is called 0-complete if the following condition is satisfied:

a nonempty set \(A \subset X\) is 0-complete if \((A,p_{|A \times A})\) is 0-complete.

In view of (2.4) a point x as in (2.5) is unique if p is a d-metric, and then \(p(x,x)= 0\).

To present a simple example of a 0-complete d-metric space let us consider \(X = [-1,\infty)\) and \(p(x,y)= x + y +2\). An easy computation shows that \(p(y,x)= 0\) yields \(x = y = -1\). In addition,

yields (2.2). Clearly, \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\) means that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty} p(-1,x_{n} ) = 0\), and \((X,p)\) is 0-complete. For \(X = (-1,\infty)\) and the same p we obtain a non-0-complete d-metric space.

Another example is \(X = \{(x_{1},x_{2}) \in \mathbb {R}^{2} : x_{1}\geq-1, x_{2}\geq0 \}\) with p defined by \(p((x_{1},x_{2}), (y_{1},y_{2})) = x_{1}+ x_{2}+ y_{1} + y_{2} + 2\).

Let us recall the notions of a partial metric due to Matthews [9], and of a dualistic partial metric due to Oltra and Valero [10] and O’Neill [11].

Definition 2.4

A dualistic partial metric is a mapping \(p : X \times X \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) such that

If p is nonnegative, then it is called a partial metric.

For details concerning the topology of a (dualistic) partial metric space see, e.g. [10].

We can see that each partial metric is a d-metric ((2.6) and (2.7) for \(p \geq0\) yield (2.1)). On the other hand, \(p(x,y)= x + y + 2\) does not necessarily mean that \(p(y,y) \leq p(y,x)\), and therefore the d-metrics in our examples are not partial metrics.

It is well known (see, e.g., [10]) that a metric d can be defined by a (dualistic) partial metric p as follows:

A dualistic partial metric space \((X,p)\) is 0-complete (see [12], Definition 2.1, [1], Corollary 4) if for every sequence such that \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty} p(x_{n},x_{m}) = 0\) there exists an \(x \in X\) such that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}d(x,x_{n}) = 0\) and \(p(x,x)= 0\).

Now, it is clear that if a partial metric space \((X,p)\) is 0-complete, then \((X,p)\) treated as a dislocated metric space is also 0-complete.

Lemma 2.5

(cf. [13], Lemma 2.2)

Let \((X,p)\) be a d-metric space with a nonempty kernel Z. Then \((Z,p_{|Z \times Z})\) is a metric subspace of \((X,p)\); if \((X,p)\) is 0-complete, then \((Z,p_{|Z \times Z})\) is complete.

Proof

Clearly, \(p_{|Z \times Z}\) is a metric on Z. From \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,x_{n}) = 0\) and

it follows that \(p(x,x)= 0\), i.e. \(x \in Z\). Therefore, if \((X,p)\) is 0-complete, then \((Z,p_{|Z \times Z})\) is complete. □

3 General contractions

In the present section we are interested in mappings \(f : X \rightarrow X\) satisfying

or

for

where \((X,p)\) is a d-metric space, and φ is a comparison function.

It should be noted that the d-metric p defines the metric δ in the following way: \(\delta(x,x) = 0\), and \(\delta(x,y) = p(x,y)\) for \(x \neq y\). One can see that a d-metric space \((X,p)\) is 0-complete (Definition 2.3) iff the metric space \((X,\delta )\) is complete.

Let us note that for \(f(y) = y\) and \(y \neq x \neq f(x)\)

does not necessarily equal

(e.g. for \(p(y,y) = 2\) and \(p \equiv1\) elsewhere). Therefore, it is better to apply the d-metric p than the metric δ.

Our theorems in the present section are new also if p is a metric. The special features of the mapping φ will enable one to give proofs of these theorems using metric δ but such full proofs would be unnecessarily complex (see also [14]).

According to the notations from [1] Φ is a class of mappings \(\varphi : [0,\infty)\rightarrow[0,\infty)\) such that \(\varphi (\alpha) < \alpha\), \(\alpha> 0\); and \(\varphi \in\boldsymbol{\Phi}_{\mathbf{0}}\) iff \(\varphi \in\Phi\) and \(\varphi (0) = 0\). In turn, \({\boldsymbol{\Phi}_{\mathbf{P}}}\) consists of mappings \(\varphi : [0,\infty)\rightarrow[0,\infty)\) for which every sequence \((a_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) such that \(a_{n+1}\leq \varphi (a_{n})\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\) converges to zero. It appears [1], Proposition 16, that \(\Phi_{P} \subset\Phi_{0}\); if \(\varphi \in\Phi_{0}\) satisfies

then \(\varphi \in\Phi_{P}\). In particular (see [1]), if \(\varphi \in \Phi_{0}\) is upper semicontinuous from the right (see [3]), then \(\varphi \in\Phi_{P}\); also, if \(\varphi \in \Phi_{0}\) is nondecreasing and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}\varphi^{n}(\alpha) = 0\), \(\alpha> 0\) (see [2]), then \(\varphi \in \Phi_{P}\).

Let us consider \(\boldsymbol{\Psi}_{\mathbf{P}}\) (\(\Phi_{P}\subset\Psi_{P} \subset \Phi\)) consisting of mappings φ for which every sequence \((a_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) such that \(0 < a_{n+1}\leq \varphi (a_{n} )\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\) converges to zero. If \(\varphi \in\Phi\) satisfies (3.4), then \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\) (see the proof of [1], Proposition 16). It was noted in [1] that Theorems 28 and 31 of that paper are valid also for \(\Phi_{P}\) replaced by \(\Psi_{P}\), as \(\varphi (0)\) is meaningless.

Example

Let us consider linear mappings \(g_{n} : \mathbb {R}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\), \(g_{n}(x) = 1 - nx\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\). One can see that \(g_{n}(1/(n+1)) = 1/(n+1)\), and \(g_{n}(1/n) = 0\). Therefore, \(\varphi \in \Phi_{0}\) defined by \(\varphi (0) = 0 = \varphi (x)\), \(x > 1\), \(\varphi (x) = g_{n}(x)\), \(x \in (1/(n+1),1/n]\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\), has the following properties:

-

(i)

\(\varphi (x) < 1/2\), \(x \in \mathbb {R}\),

-

(ii)

\(\varphi (x) < 1/(n+1)\), \(x \leq1/n\),

-

(iii)

\(\limsup_{\beta\rightarrow(1/n)^{+}} \varphi (\beta) = 1/n\), \(1 < n \in \mathbb {N}\).

Clearly, φ is not monotone, and (iii) means that (3.4) is not satisfied. If \(a_{n+1}\leq \varphi (a_{n})\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\), holds, then (i) yields \(a_{2} \leq \varphi (a_{1}) < 1/2\), and from (ii) it follows (by induction) that \(a_{n+1}\leq \varphi (a_{n}) < 1/(n+1)\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\). Consequently, we obtain \(\varphi \in\Phi_{P}\).

The subsequent two lemmas for (3.1), (3.2) are partial extensions of [1], Lemmas 25, 26, proved for partial metric spaces (see also [15], Lemmas 1, 2).

Lemma 3.1

Let X be a nonempty set, and let \(p : X \times X \rightarrow [0,\infty)\), \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be mappings satisfying condition (3.1) or (3.2), for all \(x,y \in X\) and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\). Then the condition

holds, and if \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\), then \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty }p(f^{n+1}(x),f^{n}(x)) = 0\), \(x \in X\).

Proof

For notational simplicity let us adopt \(x_{n}= f^{n}(x)\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). We have

Suppose \(p(x_{1},x) < p(x_{2},x_{1})\). Then (3.2) yields

a contradiction (\(\varphi \in\Phi\)). Now, \(m_{f}(x_{1},x) = p(x_{1},x)\) holds, and we obtain (3.5) (which for (3.1) is trivial). Now, for \(a_{n}= p(x_{n+1},x_{n})\), \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), and \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\) we get \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}a_{n}= 0\). □

Lemma 3.2

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be a mapping satisfying condition (3.1) or (3.2), for all \(x,y \in X\) and a \(\varphi \in \Phi\). If for \(x_{n}= f^{n}(x_{0})\), \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty}p(x_{n},x_{m}) = 0\) holds, then there exists a unique fixed point x of f, \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,x_{n})= 0\) (i.e. \(x = \lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}x_{n}\) in \((X,p)\)), and \(p(x,x)= 0\).

Proof

Let \(x \in X\) be such that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,x_{n})= 0\). For condition (3.1) we have

Suppose \(p(f(x),x) = \alpha> 0\). Then \(\varphi (p(x_{n},x)) \geq\alpha/2\) holds for large n, as \(p(x_{n+1},x) \rightarrow0\). Consequently, \(p(x,x_{n})= 0\) for large n, and

means that \(f(x_{n}) = x_{n}\) (see (2.1)) and \(x = x_{n}\) is a fixed point of f.

For condition (3.2), \(p(f(x),x) > 0\), and large n we have

Consequently, \(0 < p(f(x),x) \leq \varphi (p(f(x),x))\) holds, a contradiction (\(\varphi \in\Phi\)). In view of (2.1), \(p(f(x),x) = 0\) yields \(x = f(x)\).

If y is a fixed point of f, then

means that \(p(y,y) = 0\), i.e. \(y \in \operatorname {Ker}p\).

Suppose x, y are two fixed points of f. Then

means that \(p(y,x)= 0\), and \(x = y\). □

Now, we are ready to prove the following extension of [1], Theorem 27 (the proof is almost the same as in [1]).

Theorem 3.3

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be a mapping satisfying condition (3.1) or (3.2), for all \(x,y \in X\) and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\) having property (3.4) or a \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\) such that

(e.g. if φ is nondecreasing) holds. Then f has a unique fixed point; if \(x = f(x)\), then \(p(x,x)= 0\) and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,f^{n}(x_{0})) = 0\), \(x_{0}\in X\).

Proof

It is sufficient to prove that \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\) holds for \(x_{n}= f^{n} (x_{0})\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\) (see Lemma 3.2). Suppose that there are infinitely many \(k,n \in \mathbb {N}\) such that \(p(f^{n+1+k}(x_{0}),f^{k}(x_{0})) \geq\epsilon> 0\). Let \(n = n(k) > 0\) be the smallest numbers satisfying this inequality for infinitely many large k. For simplicity let us adopt \(x = f^{k}(x_{0})\) and \(x_{n}= f^{n}(x)\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\). We have

which for \(n = n(k)\) means that

as \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\) and \(\lim_{k \rightarrow\infty} p(x_{n+1},x_{n}) = \lim_{k \rightarrow\infty} p(x_{1},x) = 0\) (see Lemma 3.1). Now for \(y = x_{n}\) condition (3.2) yields

and we obtain (from (3.1) as well)

for large k. Now, \(p(x_{n},x) < \epsilon\), \(\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} p(x_{n},x) = \epsilon\), and condition (3.6) yield

a contradiction. Similarly, \(p(x_{n+1},x) \geq\epsilon\),

and condition (3.4) yield

a contradiction. Therefore, \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\) holds. □

Let us recall the following.

Lemma 3.4

[1], Lemma 29

Let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be a mapping such that \(f^{t}\) for a \(t \in \mathbb {N}\) has a unique fixed point, say x. Then x is the unique fixed point of f. If, in addition, \(x \in\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty} (f^{t})^{n}(x_{0})\), \(x_{0}\in X\), then \(x \in\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}f^{n}(x_{0})\), \(x_{0}\in X\) holds.

Now, Theorem 3.3 and Lemma 3.4 yield the following.

Theorem 3.5

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be a mapping satisfying condition (3.1) or (3.2), for all \(x,y \in X\) with f replaced by \(f^{t}\) for a \(t \in \mathbb {N}\), and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\) having property (3.4) or a \(\varphi \in\Psi _{P}\) such that (3.6) holds. Then f has a unique fixed point; if \(x = f(x)\), then x satisfies \(p(x,x)= 0\) and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,f^{n}(x_{0})) = 0\), \(x_{0}\in X\).

Kirk et al. [16] suggested the idea of cyclic mappings which was later formalized by Rus in [17] as the cyclic representation of \(X = X_{1}\cup \cdots\cup X_{t}\) with respect to f. The next definition means the same, but it is more compact.

Definition 3.6

A mapping \(f : X \rightarrow X\) is called cyclic on \(X_{1},\ldots,X_{t}\) (for a \(t > 1\)) if \(\emptyset\neq X = X_{1}\cup\cdots\cup X_{t}\), and \(f(X_{j}) \subset X_{j++} \), \(j = 1,\ldots,t\), where \(j++ = j+1\) for \(j = 1,\ldots,t-1\), and \(t++ = 1\).

Clearly, \(X_{j}\neq\emptyset\) for a j in Definition 3.6, and hence \(X_{j}\neq\emptyset\), \(j = 1,\ldots,t\).

The proof of Lemma 3.1 works also for the following.

Lemma 3.7

Let \(p : X \times X \rightarrow[0,\infty)\) be a mapping, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be cyclic on \(X_{1},\ldots,X_{t}\). Assume that (3.1) or (3.2) is satisfied for all \(x \in X_{j}\), \(y \in X_{j++}\), \(j=1,\ldots,t\), and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\). Then condition (3.5) holds, and if \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\), then \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty }p(f^{n+1}(x),f^{n}(x)) = 0\), \(x \in X\).

If we consider n such that \(x \in X_{j}\) and \(x_{n}\in X_{j++}\) for a \(j \in\{1,\ldots,t\}\), then the proof of Lemma 3.2 yields the following.

Lemma 3.8

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be cyclic on \(X_{1},\ldots,X_{t}\). Assume that (3.1) or (3.2) is satisfied for all \(x \in X_{j} \), \(y \in X_{j++}\), \(j=1,\ldots,t\), and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\). If for \(x_{n}= f^{n}(x_{0})\), \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty}p(x_{n},x_{m}) = 0\) holds, then there exists a unique fixed point x of f, \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,x_{n})= 0\) (i.e. \(x = \lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}x_{n}\) in \((X,p)\)), and \(p(x,x)= 0\).

Lemmas 3.7 and 3.8 yield the following extension of Theorem 3.3.

Theorem 3.9

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be cyclic on \(X_{1},\ldots,X_{t}\). Assume that (3.1) or (3.2) is satisfied for all \(x \in X_{j} \), \(y \in X_{j++}\), \(j=1,\ldots,t\), and a \(\varphi \in\Phi\) having property (3.4) or a \(\varphi \in\Psi _{P}\) such that (3.6) holds. Then f has a unique fixed point; if \(x = f(x)\), then \(p(x,x)= 0\) and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,f^{n} (x_{0} )) = 0\), \(x_{0}\in X\).

Proof

It is sufficient to prove that \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\) holds for \(x_{n}= f^{n} (x_{0})\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\) (see Lemma 3.8). Suppose that there are infinitely many \(k,n \in \mathbb {N}\) such that \(p(x_{(n+1)t+k+1},x_{k}) \geq \epsilon> 0\). Let \(n = n(k) > 0\) be the smallest numbers satisfying this inequality for infinitely many large k. For simplicity let us adopt \(x = x_{k} = f^{k}(x_{0})\), and \(x_{n}= f^{n}(x)\), \(n \in\mathbb{N}\). Clearly, \(x \in X_{j}\) yields \(x_{nt+1},x_{(n+1)t+1} \in X_{j++}\). We have

which for \(n = n(k)\) means that

as \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\) and \(\lim_{m \rightarrow\infty} p(x_{m+1},x_{m}) = 0\) (see Lemma 3.7). Now for \(y = x_{nt+1}\) condition (3.2) yields

and we obtain (from (3.1) as well)

for large k. Now, \(p(x_{nt+1},x) < \epsilon\), \(\lim_{k \rightarrow \infty } p(x_{nt+1},x) = \epsilon\), and condition (3.6) yield

a contradiction. Similarly, \(p(x_{(n+1)t+1},x) \geq\epsilon\),

and condition (3.4) yield

a contradiction. Now, it is clear that \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{m+nt+1},x_{m}) = 0\). Consequently,

for any \(s \in\{2,\ldots,t\}\), i.e. \(\lim_{m,n \rightarrow \infty}p(x_{n},x_{m}) = 0\). □

Karapinar and Salimi [5], Definition 1.7, have defined the notion of a generalized ϕ-ψ-contractive mapping. It appears that \(\varphi = (id + \psi )^{-1}\circ(id + \psi- \phi) \in\Phi_{P}\) because condition (3.4) is satisfied. Therefore, [5], Theorem 1.9, is a particular case of Theorem 3.3, and [5], Theorem 1.8, is a consequence of Theorem 3.9 (see also the example preceding Lemma 3.1).

Let us present cyclic mappings of the second type, i.e. those for (3.1) or (3.2) with \(x,y \in X_{j}\), \(j = 1,\ldots,t\). It is convenient to apply the idea of cross mappings introduced in [4].

Let \(F_{j} : X_{j}\rightarrow2^{E{j++}}\), \(j = 1,\ldots,t\) (for \(t > 1\)), be multivalued mappings. Then for \(Y = X_{1}\times\cdots\times X_{t}\), \(E = E_{1} \times\cdots\times E_{t}\) we define a cross mapping \(F : Y \rightarrow2^{E}\) as follows [4], (3.1):

We can see that for \(E_{j} \subset X_{j}\), \(j = 1,\ldots,t\) the composition \(F_{t} \circ F_{t-1} \circ\cdots\circ F_{1}\) has a fixed point in \(X_{1} \) iff F has a fixed point. This concept is very efficient for multivalued mappings (see [4], Section 3). Let us apply cross mappings to prove the following.

Theorem 3.10

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete d-metric space, and let \(f : X \rightarrow X\) be cyclic on 0-complete sets \(X_{1},\ldots,X_{t}\). Assume that (3.1) or (3.2) is satisfied for all \(x,y \in X_{j}\), \(j=1,\ldots,t\), and a nondecreasing \(\varphi \in\Psi_{P}\). Then f has a unique fixed point; if \(x = f(x)\), then \(p(x,x)= 0\) and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,f^{n}(x_{0})) = 0\), \(x_{0}\in X\).

Proof

Let us consider \(Y = X_{1}\times\cdots\times X_{t}\) and

Then \((Y,q)\) is a d-metric space, and it is 0-complete. If φ is nondecreasing and (3.1) or (3.2) is satisfied for p, then it is also satisfied for q, as e.g. \(\max\{\varphi (a),\varphi (b)\} = \varphi (\max\{a,b\})\). In view of Theorem 3.3 the cross mapping h defined by

has a unique fixed point. This means that \(f^{t}\) has a unique fixed point. Now we apply Lemma 3.4. □

There exist many papers concerning cyclic mappings (see, e.g., the references of [18]), and it is very likely that Theorems 3.9 and 3.10 are just a starting point for further development.

4 Variational results

In this section p is a dislocated strong quasi-metric (i.e. a dsq-metric).

To present a simple example of a 0-complete dsq-metric space let us consider \(X = [-1,\infty)\) and \(p(x,y)= x + 2y +3\). An easy computation shows that \(p(y,x)= 0\) yields \(x = y = -1\). Clearly,

yields (2.2). Moreover, (2.3) is not satisfied and therefore, p is not a d-metric. In addition, \((X,p)\) is 0-complete, as \(\lim_{n>m \rightarrow\infty }p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\) means that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(-1,x_{n}) = 0\).

Let us prove the following analog of [19], Theorem 21.

Theorem 4.1

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete dsq-metric space and \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a mapping lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp. Let us adopt \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi (y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\), \(x,y \in X\), and assume that ψ is bounded below on each chain and the following holds:

Then for any \(x_{0}\in X \setminus B\), each maximal chain \(A \subset X \) containing \(x_{0}\) has a unique smallest element x, in addition satisfying

-

(i)

\(\psi(x) = \inf\{\psi(z) : z \in A\}\) and \(x \in B\),

-

(ii)

\(\psi(x) + p(x,x_{0}) - \psi(x_{0}) = \inf\{\psi(z) + p(z,x_{0}) - \psi(x_{0}) : z \in A \} \leq0\),

-

(iii)

\(0 < \psi(y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x)\), for each \(y \in X \setminus\{x\}\),

-

(iv)

\(x \in \operatorname {Ker}p\) (i.e. \(p(x,x)= 0\) if p is a d-metric).

Proof

The relation ≼ is transitive and in view of Kuratowski’s lemma [7], p.33, for any \(x_{0}\in X \setminus B\) there exists a maximal chain A containing \(x_{0} \). Let us adopt \(\alpha= \inf\{ \psi(z) : z \in A \}\) and suppose \(\alpha< \psi (x)\), for each \(x \in A\). Then there exists a sequence \((x_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) in A such that \((\psi(x_{n}))_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) decreases to α. For any \(y \in A\) such that \(\psi(x_{n}) < \psi(y)\) the condition \(y \preccurlyeq x_{n}\) cannot hold, as then

Therefore, if \(y \in A\) and \(\psi(x_{n}) < \psi(y)\), then \(x_{n}\preccurlyeq y\). In particular, \(m < n\) yields \(x_{n}\preccurlyeq x_{m}\), i.e.,

and consequently, \(\lim_{n>m \rightarrow\infty}p(x_{n},x_{m})= 0\), as ψ is bounded below on A. Therefore, there exists an x such that \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}p(x,x_{n})= 0\), i.e. \(x \in \operatorname {Ker}p\) (see Definition 2.1), and \(p(x,x)=0\) if p is a d-metric (see (2.4)). Clearly,

is lower semicontinuous at x (see Proposition 2.2). Now, we obtain

i.e. \(x \preccurlyeq x_{m}\), and \(\psi(x) \leq\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}\psi(x_{n}) = \alpha\). For any \(y \in A\) and \(\psi(x_{m}) < \psi(y)\) we get \(x \preccurlyeq x_{m}\preccurlyeq y\). Consequently, \(x \in A\) and (iv) is satisfied. Suppose a \(y \in A \setminus\{x\}\) such that \(\psi(y) = \alpha\). Then \(0 \leq\min\{p(x,y),p(y,x)\} \leq|\psi(y) - \psi(x)| = 0\) yields \(x = y\). Therefore, x is the unique smallest element of A and conditions (ii), (iii) follow. In view of (4.1) \(x \in B\), and we get (i). □

The ‘order’ reasoning fails for a quasi-metric (\(x = y\) iff \(q(x,y) = q(y,x) = 0\), \(q(z,x) \leq q(z,y) + q(y,x)\)), as \(q(y,x) = 0\) does not necessarily yield \(q(x,y) = 0\).

A reasoning similar to the one presented in the above proof yields the following analog of [19], Theorem 22.

Theorem 4.2

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete dsq-metric space and \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a mapping lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp. Let us adopt \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi(y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\), \(x,y \in X\), and assume that \(x_{0} \in X\) belongs to a chain and ψ is bounded below on each chain containing \(x_{0}\). Then each maximal chain \(A \subset X \) containing \(x_{0}\) has a unique smallest element x, in addition satisfying

-

(i)

\(\psi(x) = \inf\{\psi(z) : z \in A\}\),

-

(ii)

\(\psi(x) + p(x,x_{0}) - \psi(x_{0}) = \inf\{\psi(z) + p(z,x_{0}) - \psi(x_{0}) : z \in A \} \leq0\),

-

(iii)

\(0 < \psi(y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x)\), for each \(y \in X \setminus\{x\}\),

-

(iv)

\(x \in \operatorname {Ker}p\) (i.e. \(p(x,x)= 0\) if p is a d-metric).

Proof

In view of Kuratowski’s lemma [7], p.33, there exists a maximal chain A containing \(x_{0}\). Now, for A we follow the proof of Theorem 4.1, omitting the last sentence. □

We also have the following analog of [19], Theorem 23.

Theorem 4.3

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete dsq-metric space and \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a mapping lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp. Let us adopt \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi (y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\), \(x,y \in X\), and assume that ψ is bounded below on each chain. If \(X \subset Y\) and \(F : X \rightarrow2^{Y}\) is a mapping satisfying

Then for any \(x_{0}\in X\), \(x_{0}\in F(x_{0})\) holds or each maximal chain \(A \subset X \) containing \(x_{0}\) has a unique smallest element x, which in addition satisfies conditions (i), … , (iv) of Theorem 4.2 and is such that \(x \in F(x)\).

Proof

If \(x_{0}\notin F(x_{0})\), then Theorem 4.2 applies and (iii) contradicts (4.2) for \(x \notin F(x)\). □

The subsequent theorem extends the theorems of Caristi [20], Theorem (2.1)′, and Takahashi [21], Theorem 5.

Theorem 4.4

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete dsq-metric space and \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a mapping lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp. Let us adopt \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi (y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\), \(x,y \in X\), and assume that ψ is bounded below on each chain. If \(X \subset Y\) and \(F : X \rightarrow2^{Y}\) is a mapping satisfying

Then for any \(x_{0}\in X\), each maximal chain \(A \subset X \) containing \(x_{0}\) has a unique smallest element x, which in addition satisfies conditions (i), … , (iv) of Theorem 4.2 and is such that \(x \in F(x)\).

Proof

In view of (4.3) Theorem 4.2 works. Now condition (4.3) and (iii) mean that \(x \in F(x)\). □

The subsequent theorem extends Ekeland’s variational principle [22], Theorem 1, (cf. [19], Theorem 25, and [23], Theorem 3).

Theorem 4.5

Let \((X,p)\) be a 0-complete dsq-metric space and \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) a bounded below mapping lower semicontinuous at points of Kerp. Let us adopt \(y \preccurlyeq x\) iff \(\psi(y) + p(y,x) - \psi(x) \leq0\), \(x,y \in X\), and assume that \(x_{0} \in X\) belongs to a chain (e.g. if \(p(x_{0},x_{0}) = 0\)). Then the following conditions are satisfied:

-

(a)

there exists an \(x \in X\) such that \(\psi(x) \leq\psi (x_{0})\) and \(\psi(x) - p(y,x) < \psi(y)\), for each \(y \in X \setminus\{x\}\),

-

(b)

for any \(\epsilon> 0\) and each \(x_{0}\in X\) with \(p(x_{0} ,x_{0}) = 0\) there exists an \(x \in X\) such that \(\psi(x) \leq\psi(x_{0})\), and \(\psi(x) - \epsilon p(y,x) < \psi(y)\), for each \(y \in X \setminus\{x\}\); if, in addition, \(\psi(x_{0}) \leq\epsilon+ \inf\{\psi(z) : z \in X \}\) holds, then \(p(x,x_{0}) \leq1\).

Proof

Clearly, Theorem 4.2 (i), (iii) yield (a). If we consider ϵp in place of p for \(p(x_{0},x_{0}) = 0\), then for the smallest element x in any maximal chain A containing \(x_{0}\) we have \(\psi(x) \leq\psi(x_{0})\), and \(0 < \psi(y) + \epsilon p(y,x) - \psi (x)\), \(y \in X \setminus\{x\}\) (Theorem 4.2(i), (iii)). From \(\epsilon p(x,x_{0}) \leq\psi(x_{0}) - \psi(x)\) (Theorem 4.2(ii)) and the second assumption of (b) we obtain

□

Kirk and Saliga [24], p.2769, say that for a Hausdorff space \((X,\tau)\) a mapping \(\psi: X \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is τ-lower semicontinuous from above if given any sequence \((x_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) in X, the conditions: \((\psi(x_{n}))_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) decreases to α and \(\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty}x_{n}= x\), yield \(\psi(x) \leq\alpha\). The proof of Theorem 4.1 works without any change if we relax in such a way the assumption of lower semicontinuity of ψ at points of Kerp (we may then say that ψ is lower semicontinuous from above at the points of Kerp). Consequently, all results of the present section stay valid with this weaker assumption.

It should be noted that the dislocated (strong quasi-)metric p defines the (quasi-)metric δ in the following way: \(\delta(x,x) = 0\), and \(\delta(x,y) = p(x,y)\) for \(x \neq y\). One can see that a dislocated (strong quasi-)metric space \((X,p)\) is 0-complete (Definition 2.3) iff the (quasi-)metric space \((X,\delta)\) is complete (for the quasi-metric, see [19], Definitions 14, 7).

Consequently, if a proof of a fixed point theorem for complete metric spaces is based on a sequence \((x_{n})_{n \in\mathbb{N}}\) that converges to a fixed point, \(\delta (x_{n},x_{n+1}) \neq0\), \(n \in\mathbb{N} \) (and \(\delta(x_{n},x_{n}) = 0\) can be disregarded), then the same proof works for 0-complete d-metric spaces, and further, for 0-complete partial metric spaces.

Another method is to prove that \(Z = \operatorname {Ker}p\) is nonempty, \(f_{|Z} : Z \rightarrow Z\), and to apply Lemma 2.5 (see comments on Theorems 2.3 and 2.4 [13]).

References

Pasicki, L: Fixed point theorems for contracting mappings in partial metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2014, 185 (2014)

Matkowski, J: Integrable solutions of functional equations. Diss. Math. 127, 1-68 (1975)

Boyd, DW, Wong, JSW: On nonlinear contractions. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 20, 458-464 (1969)

Pasicki, L: A fixed point theory and some other applications of weeds. Opusc. Math. 7, 1-96 (1990)

Karapinar, E, Salimi, P: Dislocated metric space to metric spaces with some fixed point theorems. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2013, 222 (2013)

Hitzler, P, Seda, K: Dislocated topologies. J. Electr. Eng. 51(12), 3-7 (2000)

Kelley, JL: General Topology. Springer, Berlin (1975)

Amini-Harandi, A: Metric-like spaces, partial metric spaces and fixed points. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2012, 204 (2012)

Matthews, SG: Partial metric topology. Proc. 8th Summer Conference on General Topology and Applications. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 728, 183-197 (1994)

Oltra, S, Valero, O: Banach’s fixed point theorem for partial metric spaces. Rend. Ist. Mat. Univ. Trieste 36, 17-26 (2004)

O’Neill, SJ: Partial metrics, valuations, and domain theory. Proc. 11th Summer Conference on General Topology and Applications. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 806, 304-315 (1996)

Romaguera, S: A Kirk type characterization of completeness for partial metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2010, Article ID 493298 (2010)

Pasicki, L: Partial metric, fixed points, variational principles. Fixed Point Theory (2016, to appear)

Haghi, RH, Rezapour, S, Shahzad, N: Be careful on partial metric fixed point results. Topol. Appl. 160, 450-454 (2013)

Romaguera, S: Fixed point theorems for generalized contractions on partial metric spaces. Topol. Appl. 159, 194-199 (2012)

Kirk, WA, Srinivasan, PS, Veeramani, P: Fixed points for mappings satisfying cyclical contractive conditions. Fixed Point Theory 4, 79-89 (2003)

Rus, IA: Cyclic representation and fixed points. Ann. “Tiberiu Popoviciu” Sem. Funct. Equ. Approx. Convexity 3, 171-178 (2005)

Alghamdi, MA, Shahzad, N, Valero, O: On fixed point theory in partial metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2012, 175 (2012)

Pasicki, L: Variational principles and fixed point theorems. Topol. Appl. 159, 3243-3249 (2012)

Caristi, J: Fixed point theorems for mappings satisfying inwardness conditions. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 215, 241-251 (1976)

Granas, A, Horvath, CD: On the order-theoretic Cantor theorem. Taiwan. J. Math. 4, 203-213 (2000)

Ekeland, I: Nonconvex minimization problems. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 1, 443-474 (1979)

Kada, O, Suzuki, T, Takahashi, W: Nonconvex minimization theorems and fixed point theorems in complete metric spaces. Math. Jpn. 44, 381-391 (1996)

Kirk, WA, Saliga, LM: The Brézis-Browder order principle and extensions of Caristi’s theorem. Nonlinear Anal. 47, 2765-2778 (2001)

Acknowledgements

The author is obliged to Pascal Hitzler and Anthony Karel Seda for their old idea of dislocated metric (thankfully known to the referee), which is identical to the ‘new’ concept of near metric. That is why the former version of this manuscript entitled ‘Near (quasi-)metric and fixed point theorems’ (sent to FPTAppl in December 2014) had to be rearranged to the present form). The work has been supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pasicki, L. Dislocated metric and fixed point theorems. Fixed Point Theory Appl 2015, 82 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-015-0328-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-015-0328-z