Abstract

We analyze the stability of positive equilibrium in a predator-prey model with time delay τ and subsidies. The sufficient conditions of the local Hopf bifurcations at the positive equilibrium are obtained. By center manifold theorem and normal form theory, we analyze the direction of Hopf bifurcations and stability of the bifurcating periodic solution. Using the global Hopf bifurcation theorem, we find that each connected component is unbounded. High-dimensional Bendixson theorem is used to prove that the system has no nonconstant periodic solutions of τ-period, then we obtain the global existence of periodic solutions. Finally, a numerical example is performed to support the theoretical results, and the effect of the food subsidy is discussed. We find that the food subsidy will make the stable interval \([0,\tau _{0})\) of positive equilibrium larger with \(\tau _{0}\) the first Hopf bifurcation value.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Predator-prey mechanism has been analyzed for almost a century since Lotka and Volterra [1, 2] established the first predator-prey model on the basis of population dynamics. Regarding the subject, many scholars are still working on different kinds of the mathematical model. For example, the authors in [3] analyzed the multiple bifurcation problem of a predator-prey model with nonmonotonic functional reaction function. The authors in [4] investigated the population relation between prey and predator in ecology. In the year 2012, Nevai et al. established a model about prey, predator, and subsidies [5] and discussed the dynamical behavior of such systems. Recently, time delay effect has been proved to significantly affect the dynamics of predator-prey models [6, 7]. Thus, in this paper, we consider the effect of time delay τ on the model given in [5], which leads to the delay differential equation model

where \(x(t)\), \(y(t)\) stand for the density of prey and predator species at time t, respectively. \(s(t)\) represents resource subsidies, r is the inherent growth rate of the prey, K is its carrying capacity, θ represents the maximum rate at which predators can consume prey, i is the rate at which the subsidy appears, γ is its vanishing rate or inedibility, ψ is the maximum rate at which predators can consume subsidies, ε and η are conversion factors, e is a half-saturation constant, δ is the mortality rate of the predator, and τ is conversion time delay. We assume that all constants are positive and \(\varepsilon \theta > \delta \), \(\eta \psi > \delta \), which means that the natural death rate of the predator is not very high compared with the conversion rate. Otherwise, the predator’s per-capita growth rate is always negative.

In this paper, we first investigate the effect of time delay on the stability of the positive equilibrium by analyzing the roots’ distribution of the associated characteristic equation. We find that time delay will destabilize the equilibrium and induce Hopf bifurcation at a sequence of critical values. The direction of Hopf bifurcation and the stability of Hopf bifurcating periodic solutions are investigated on the center manifold of the equilibrium by deriving the simplest normal form. The method is based on the framework introduced by Hassard et al. [8], where explicit formulas determining the properties of Hopf bifurcation are given. In fact, these results are obtained locally near the bifurcation points. To study the global continuation of Hopf bifurcating periodic solutions, we also investigate the properties of Hopf branches by using the global Hopf bifurcation theorem established by [9] which has also been widely used by many scholars such as in [10]. One key step in proving the global existence is to rule out the existence of nonconstant τ-period solutions by using the high-dimensional Bendixson’s theorem established by [11]. Finally, some simulations are performed by numerically solving system (1) and the simulation package DDE-Biftool [12, 13].

This paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, we investigate the existence and stability of positive equilibria and obtain sufficient conditions for local Hopf bifurcations at the positive equilibrium. Then, by using the center manifold theorem and normal form theory, we obtain the properties of Hopf bifurcations. In Sect. 3, by using global Hopf bifurcation theory, we analyze the global Hopf bifurcation, and we give some simulations in Sect. 4. Finally, some conclusions complete this paper.

2 Stability and local Hopf bifurcation

In this section, we mainly investigate the stability of the unique equilibrium of system (1) by analyzing the corresponding characteristic equation and prove that there exist local Hopf bifurcations when increasing the time delay. By the center manifold theorem and normal form theory provided by [8], we obtain the properties of Hopf bifurcation, including the direction of Hopf bifurcation and stability of the bifurcating periodic solution.

2.1 Positive equilibria

First, we give the existence of equilibria of system (1). Obviously, \(E_{1}=(0,\frac{i}{\gamma },0)\) and \(E_{2}=(K,\frac{i}{ \gamma },0)\) are two boundary equilibria of system (1). When \(i>\gamma \bar{l}\), \(E_{3}=(0,\bar{l}, \frac{\eta (i-\gamma \bar{l})}{ \delta })\) is also a boundary equilibrium of system (1), where \(\bar{l}=\frac{e\delta }{\eta \psi -\delta }\). In fact, what we are interested in is the existence of positive equilibria of system (1). Suppose that \(E^{\ast }=(x^{\ast },s^{\ast },y^{\ast })\) is a positive equilibrium of system (1) with \(x^{\ast },s ^{\ast },y^{\ast }>0\), then \((x^{\ast },s^{\ast },y^{\ast })\) must satisfy

Due to \(x^{\ast }, y^{\ast }>0\), we can obtain \(s^{\ast }\) satisfies

and

where \(\bar{l} = {{e\delta } / { ( {\eta \psi - \delta } )}}\) and \(\bar{K} = {{e\delta } / { ( {\varepsilon \theta - \delta } )}}\). According to the results given in [5], we have the following result about the existence of positive equilibrium.

Theorem 1

System (1) has a unique positive equilibrium \(E^{\ast }\) when one of the following two conditions is satisfied:

-

(i)

\(K<\bar{K}\) and \(i_{\ast }(K)< i< i^{\ast }\);

-

(ii)

\(K>\bar{K}\) and \(i< i^{\ast }\),

where \(\bar{K} = \frac{{e\delta }}{{\varepsilon \theta - \delta }}\), \({i^{*} } = ( {\gamma + \frac{{r\psi }}{\theta }} ) \bar{l}\), \({i_{*} } ( K ) = ( {1 - \frac{K}{{\bar{K}}}} )\gamma \bar{l}\), and \(\bar{l} = \frac{ {e\delta }}{{\eta \psi - \delta }}\).

2.2 Stability and existence of Hopf bifurcation

In this section we shall study the stability of the positive equilibrium \(E^{\ast }\). For convenience, let \(u_{1}(t)=x(t)-x^{\ast }\), \(u_{2}(t)=s(t)-s^{\ast }\), \(u_{3}(t)=y(t)-y^{\ast }\), then we have the linearized equation

where \({a_{11}} = r ( {1 - \frac{{2{x^{*} }}}{K}} ) - \frac{ {\theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} ){y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{12}} = \frac{{\theta {x^{*} }{y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{13}} = - \frac{{\theta {x^{*} }}}{\nu }\), \({a_{21}} =\frac{{\psi {s^{*} }{y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{22}} = - \gamma - \frac{{\psi {y^{*} } ( {{x^{*} } + e} )}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{23}} = - \frac{{\psi {s^{*} }}}{\nu }\), \({a_{31}} = \frac{{\varepsilon \theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} ) - \eta \psi {s^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}} {y^{*} }\), \({a_{32}} = \frac{{\eta \psi ( {{x^{*} } + e} ) - \varepsilon \theta {x^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}{y^{*} }\), and \(\nu = {x^{*} } + {s^{*} } + e\).

The characteristic equation of system (2) is

where \(A=-(a_{11}+a_{22})\), \(B=(a_{11}a_{22}-a_{21}a_{12})\), \(C=-(a_{23}a_{32}+a_{31}a_{12})\), and \(D=a_{11}a_{23}a_{32}-a_{21}a _{13}a_{32}-a_{31}a_{12}a_{23}-a_{31}a_{13}a_{22}\).

Now, we discuss the distribution of the roots of Eq. (3) by using the method given in [14, 15]. First we state the following lemma which is useful for analyzing the characteristic equations.

Lemma 1

(Ruan and Wei [14])

Suppose that \(B\subset \mathrm{R}^{n}\) is an open connected set, the characteristic exponential polynomial \(h(\lambda , \tau )\) is continuous in \((\lambda ,\tau )\in \mathrm{C}\times B \) and analytic in \(\lambda \in \mathrm{C}\); and the zeros of \(h(\lambda , \tau )\) in the right half plane

are uniformly bounded. If for any \(\tau \in B_{1}\subset B\), where \(B_{1}\) is a bounded, closed, and connected set, \(h(\lambda , \tau )\) has no zeros on the imaginary axis, then the sum of the orders of the zeros of \(h(\lambda , \tau )\) in the open right half plane (\(\operatorname{Re} \lambda > 0\)) is a fixed number for \(B_{1}\).

When \(\tau =0\), Eq. (3) becomes

By the well-known Routh–Hurwitz criterion, the sufficient and necessary condition that all the roots of Eq. (4) have a negative real part is

When \(\tau >0\), substituting \(\lambda =i\omega \) into Eq. (3), we have

Separating the real and imaginary parts gives

From Eq. (5), we have

Let \(z = {\omega ^{2}}\), then

Denote \(p = {A^{2}} - 2B\), \(q = {B^{2}} - {C^{2}}\), \(q = {B^{2}} - {C^{2}}\), and \(r = - {D^{2}} \), then we have

Let

Obviously, \(h ( 0 ) = r < 0\), \(\lim_{z \to \infty }h ( z ) = \infty \). Thus, Eq. (7) has at least one positive root. From (8) we have

Let

then roots of Eq. (9), i.e., the local extreme values of \(h(z)\), can be written as

with \(\Delta = {{p^{2}} - 3q}\).

If \(\Delta <0\), then Eq. (9) has no real roots and \(h(z)\) is monotonically increasing with z. Thus Eq. (7) has only one positive solution. If \(\Delta \geq 0\), then

is the local minimum value of \(h(z)\);

is the local maximum value of \(h(z)\). Thus, we have the following conclusions.

Lemma 2

For Eq. (7),

-

(1)

when \(\Delta >0\), \(z_{a}>0\), \(h(z_{a})>0\), and \(h(z_{b})<0\), Eq. (7) has three positive roots;

-

(2)

when \(\Delta >0\), \(z_{a}>0\), \(h(z_{a})>0\), and \(h(z_{b})=0\), Eq. (7) has two positive roots;

-

(3)

in other cases, Eq. (7) has only one positive root.

Now we suppose that Eq. (7) has three positive roots \(z_{1}\), \(z_{2}\), and \(z_{3}\), then Eq. (6) has three positive roots correspondingly, \({\omega _{k}} = \sqrt{{z_{k}}} \), \(k = 1,2,3\). From Eq. (5), we have

then the critical values of τ can be expressed by

\({k = 1,2,3,j = 0,1, \ldots }\). Therefore, \(\pm {\mathrm{{i}}}{\omega _{k}}\) are a pair of imaginary roots of Eq. (3) when \(\tau = \tau _{k}^{ ( j )}\), \(k = 1,2,3\); \(j = 0,1, \ldots \) .

Define \({\tau _{0}} = \tau _{k_{0}}^{ ( 0 )} = \mathrm{ {mi}}{\mathrm{{n}}_{k \in \{ {1,2.3} \}}} \{ {\tau _{k}^{(0)}} \}\), and \({\omega _{0}} = {\omega _{{k_{0}}}}\). Suppose that \(\lambda ( \tau ) = \alpha ( \tau ) + \mathrm{ {i}}\beta ( \tau )\) is a root of Eq. (3) satisfying \(\alpha ( {{\tau _{0}}} ) = 0\), \(\omega ( {{\tau _{0}}} ) = {\omega _{0}}\), then we have the following conclusion.

Lemma 3

If Eq. (7) has only one positive root z̄, that is, there only exists one sequence of \(\tau _{k}, k=1,2,\ldots \) , then the following condition holds true:

Proof

In fact, we have

thus, we have

and

□

Now, we are in a position to state the stability and Hopf bifurcation results about system (1) based on the fundamental Hopf bifurcation Theorem in [16, 17].

Lemma 4

(Hale and Verduyn Lunel [17])

Consider the functional differential equation \(\dot{x}(t)=F(\alpha ,x_{t})\), where F has continuous first and second derivatives in α and ϕ with \(F(\alpha ,0)=0\) for all α. Define \(L(\alpha )\psi =D_{\phi }F(\alpha ,0) \psi \). Assume that \(\dot{x}(t)=L(0)x_{t}\) has a simple purely imaginary characteristic root \(\lambda _{0}=\mathrm {i}\omega \) and all characteristic roots \(\lambda \neq \pm \mathrm {i}\omega \) satisfy \(\lambda \neq m\lambda _{0}\) for any integer m. Assume further that Re\(\lambda '(0)\neq 0\). Then \(\alpha =0\) is a Hopf bifurcation point in the sense described by Theorem 1.1 in [17].

In fact, condition \((H1)\), which means the characteristic equation has no roots on the right half plane when \(\tau =0\), is important for the system to undergo Hopf bifurcations at the stability boundary of the positive equilibrium. Choose the parameter interval \(B_{1}=[0, \hat{\tau }]\) as stated in Lemma 1 with \(\hat{\tau }< \tau _{0}\), then we know that the characteristic equation has no roots on the right half plane for any \(\tau \in [0,\hat{\tau }]\), i.e., the equilibrium is asymptotically stable when \(\tau \in [0,\tau _{0})\). When τ increases from zero, \(\tau _{0}\) is the first critical value at which the characteristic equation has roots on the imaginary axis. This means that all roots except \(\pm \mathrm {i}\omega \) have a negative real part when \(\tau =\tau _{0}\), then we have the following stability and Hopf bifurcation results by applying the above Lemmas 1–4.

Theorem 2

Assume that \((H1)\) holds true, then for \(\tau \in [0,{\tau _{0}})\), the positive equilibrium \(E^{\ast }\) of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable; furthermore, if case \((3)\) in Lemma 2 holds true, then when \(\tau > {\tau _{0}}\), the positive equilibrium \(E^{\ast }\) of system (1) is unstable. Moreover, when \(\tau = {\tau _{k}}\), system (1) undergoes a Hopf bifurcation at \(E^{*}\).

Remark 1

Obviously, \((H1)\) has extremely complicated expressions in terms of the original parameters from system (1). Analyzing this assumption theoretically is impossible, but instead, we will give some numerical examples to illustrate the existence of Hopf bifurcations. Figure 1 illustrates the region where \((H1)\) holds true in the \(K-i\) plane and \(\gamma -i\) plane, respectively. The parameters are chosen from [5] as \(r=0.1\), \(\theta =5\), \(e=1\), \(\psi =5\), \(\epsilon =0.1\), \(\eta =0.1\), \(\delta =0.1\). In the left figure we use \(\gamma =1\) and in the right \(K=0.2\). Numerically, we have that both large or small food subsidy i may destabilize the positive equilibrium.

2.3 Properties of Hopf bifurcation

Now we investigate the property of Hopf bifurcation by using the method given in [8]. Introduce a new perturbation parameter \(\mu = \tau - {\tau _{0}}\) with \(\mu \in R\), then \(\mu = 0\) is a Hopf bifurcation value of system (1). Let \({u_{1}} ( t ) = x ( t ) - {x^{*} }\), \({u_{2}} ( t ) = s ( t ) - {s^{*} }\), \({u_{3}} ( t ) = y ( t ) - {y^{*} }\), then system (1) becomes an equation in the phase space \(C = C ( { [ { - {\tau _{0}},0} ], {R^{3}}} )\)

where \(u ( t ) = { ( {{u_{1}}(t), {u_{2}}(t), {u_{3}}(t)} )^{\mathrm{T}}} \in {R^{3}}\), \(L:C \to {R^{3}}\), \(F:{R^{3}} \times C \to {R^{3}}\), with

\(B_{1}\) and \(B_{2}\) are defined by the following form:

and

where \({a_{14}} = - \frac{r}{K} + \frac{{\theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} ){y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{15}} = - \frac{{\theta {x^{*} } {y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{16}} = \frac{{\theta {y^{*} } ( {{s^{*} } + e - {x^{*} }} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{17}} = - \frac{ {\theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} )}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{18}} = \frac{ {\theta {x^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{24}} = - \frac{{\psi {s^{*} } {y^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{25}} = \frac{{\psi {y^{*} } ( {{x^{*} } + e} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{26}} = \frac{{\psi {y^{*} } ( {{x^{*} } + e - {s^{*} }} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{27}} = \frac{{\psi {s^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{28}} = - \frac{ {\psi ( {{x^{*} } + e} )}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{34}} = - \frac{ {{y^{*} } ( {\varepsilon \theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} ) - \eta \psi {s^{*} }} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{35}} = - \frac{ {{y^{*} } ( {\eta \psi ( {{x^{*} } + e} ) - \varepsilon \theta {x^{*} }} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{36}} = \frac{{\varepsilon \theta {y^{*} } ( {{x^{*} } - {s^{*} } - e} ) + \eta \psi {y^{*} } ( {{s^{*} } - {x^{*} } - e} )}}{{{\nu ^{3}}}}\), \({a_{37}} = \frac{{\varepsilon \theta ( {{s^{*} } + e} ) - \eta \psi {s^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), \({a_{38}} = \frac{{\eta \psi ( {{x^{*} } + e} ) - \varepsilon \theta {x^{*} }}}{{{\nu ^{2}}}}\), and \(a_{11}\), \(a_{12}\), \(a_{13}\), \(a_{21}\), \(a_{22}\), \(a_{23}\), \(a_{31}\), \(a_{32}\) are given in (2).

From the Riesz representation theorem, there exists a function \(\eta ( {\theta ,\mu } )\) of bounded variance such that

In fact, we can choose

and for \(\varphi \in {C^{1}} ( { [ { - {\tau _{0}},0} ], {R^{3}}} )\), define the operator \(A ( \mu )\):

and

then system (1) is equivalent to the following abstract ordinary differential equation:

where \({u_{t}} = u ( {t + \theta } )\) and \(\theta \in [ { - {\tau _{0}},0} ]\).

For \(\psi \in {C^{1}} ( { [ {0,{\tau _{0}}} ], {R ^{3}}} )\), define \(A^{\ast }\), the adjoint operator of A, by

and a bilinear product

where \(\eta ( \theta ) = \eta ( {\theta , 0} )\).

We know that \(\pm {\mathrm{{i}}}{\omega _{0}}\) are eigenvalues of \(A(0)\), so are the eigenvalues of \(A^{\ast }(0)\), that is, \(A ( 0 )q ( \theta ) = \mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}q ( \theta )\) and \({A^{*} } ( 0 )q{}^{*} ( s ) = - \mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}{q^{*} } ( s )\). Suppose that \(q ( \theta ) = { ( {1,\alpha ,\beta } ) ^{\mathrm{T}}}{\mathrm{{e}}^{\mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}\theta }}\) and \({q^{*} } ( s ) = D ( {1,{\alpha ^{*} },{\beta ^{*} }} ){\mathrm{{e}}^{\mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}s}}\) are the corresponding eigenfunctions. By calculation we have

From \(\langle {{q^{*}},q} \rangle = 1\), we have

then

Define

on the center manifold \(C_{0}\). \(w ( {t, \theta } ) = w ( {z ( t ), \bar{z} ( t ), \theta } )\), where \(w ( {z, \bar{z}, \theta } )\) can be written as a power series form of z and z̄

Thus we have

which is denoted by

where

Using the algorithm given in the Appendix, we have \(g_{21}\) and

According to the fundamental results about Hopf bifurcations [8], these quantities determine the properties of Hopf bifurcation at \(\tau _{0}\), precisely we state the main results given in [8].

Lemma 5

(Hassard et al. [8])

There exist \(\epsilon _{H}>0\) and an analytic function \(\mu ^{H}(\bar{\epsilon })=\mu _{2}\bar{\epsilon }^{2}+\cdots\) such that, for each \(\bar{\epsilon }\in (0,\epsilon _{H})\), there exists a periodic solution occurring for \(\mu =\mu ^{H}(\bar{\epsilon })\), whose period is an analytic function \(T^{H}(\bar{\epsilon })=\frac{2\pi }{ \omega _{0}\tau _{0}}(1+T_{2}\bar{\epsilon }^{2}+\cdots)\). One of the Floquet exponents of the periodic solution is zero and the other is an analytic function \(\beta ^{H}(\bar{\epsilon })=\beta _{2}\bar{\epsilon }^{2}+\cdots\) .

By using Lemma 5, we have the following Hopf bifurcation results about system (1).

Theorem 3

In a neighborhood of \(\mu =0\), the following statements hold:

-

(1)

\(\mu _{2}\) determines the direction of Hopf bifurcation: if \(\mu _{2}>0\) (<0), then Hopf bifurcation is forward (backward), i.e., bifurcation periodic solutions exist for \(\tau >\tau _{0}\) (\(\tau <\tau _{0}\));

-

(2)

\(\beta _{2}\) determines the stability of Hopf bifurcating periodic solutions: if \(\beta _{2}<0\) (>0), then the Hopf bifurcating periodic solution is orbitally asymptotically stable (unstable) restricted on the center manifold;

-

(3)

\(T_{2}\) affects the period: if \(T_{2}>0\) (<0), then the period increases (decreases).

3 Global Hopf bifurcation analysis

In this section, we shall study the global continuation of Hopf bifurcation by employing the global Hopf bifurcation theorem given by Wu [9] and the high dimensional Bendixson theorem established by Li and Muldowney [11]. Similar derivations can also be found in [10].

3.1 Global Hopf bifurcation theorem

Suppose \(R_{+} ^{3} = \{ { ( {x, s, y} ) \in R ^{3}, x > 0, s > 0, y > 0} \}\), \(X = C ( { [ { - \tau , 0} ], R_{+} ^{3}} )\), \({z_{t}} = ( {x ( t ), s ( t ),y ( t )} ) \in X\). Define \({z_{t}} ( \theta ) = ( {{z_{1}} ( {t + \theta } ), {z_{2}} ( {t + \theta } ), {z_{3}} ( {t + \theta } )} )\), \(t \ge 0\), \(\theta \in [ { - \tau ,0} ]\).

On \(R^{3}_{+}\), using similar notations as those in [9], we consider system (1), which can be rewritten as the following form:

where \(( {\tau ,p} ) \in {R_{+} } \times {R_{+} }\), \({R_{+} } = [ {0, + \infty } )\), and \(F:X \times {R_{+} } \times {R_{+} } \to R _{+} ^{3}\) is completely continuous. If we restrict F onto the subspace of constant functions, then we have \(\hat{F} = F{|_{R_{+} ^{3} \times {R_{+} } \times {R_{+} }}}:R_{+} ^{3} \times {R_{+} } \times {R_{+} } \to R_{+} ^{3}\).

Denote the constant mapping \(z_{0}\in R_{+}^{3}\) by \(\bar{z}_{0}\). If \(\hat{F} ( {{{\bar{z}}_{0}}, {\tau _{0}}, {p_{0}}} ) = 0\), we say \(( {{{\bar{z}}_{0}}, {\tau _{0}}, {p_{0}}} )\) is a stationary solution of (11). Obviously, we have

-

(A1)

\(\hat{F} \in {C^{2}} ( {R_{+} ^{3} \times {R_{+} } \times {R_{+} }, R_{+} ^{3}} )\).

From system (1), we know

Under assumption \((H1)\), we obtain

Thus, about the linear operator \({D_{z}}\hat{F} ( {z,\tau ,p} )\), we have

-

(A2)

The derivative \({D_{z}}\hat{F} ( {z,\tau ,p} )\) at equilibrium \(z^{\ast }\) is a homomorphism on \(R_{+}^{3}\);

-

(A3)

\(F(\phi ,\tau ,p)\) is differentiable with respect to ϕ.

The characteristic matrix of (11) at \((\bar{z}_{0},\tau _{0},p)\) is

that is,

where \({m_{1}} = - r ( {1 - \frac{{2{{\bar{z}}^{ ( 1 )}}}}{K}} ) + \frac{{\theta ( {{{\bar{z}}^{ ( 2 )}} + e} ){{\bar{z}}^{ ( 3 )}}}}{{{{ ( {{{\bar{z}}^{ ( 1 )}} + {{\bar{z}}^{ ( 2 )}} + e} )}^{2}}}}\), \({m_{2}} = \gamma + \frac{{\psi {{\bar{z}}^{ ( 3 )}} ( {{{\bar{z}} ^{(1)}} + e} )}}{{{{ ( {{{\bar{z}}^{ ( 1 )}} + {{\bar{z}}^{(2)}} + e} )}^{2}}}}\), and \({m_{3}} = \delta - \frac{ {\varepsilon \theta {{\bar{z}}^{ ( 1 )}} + \eta \psi {{\bar{z}}^{ ( 2 )}}}}{{{{\bar{z}}^{ ( 1 )}} + {{\bar{z}}^{ ( 2 )}} + e}}\).

The roots of \(\operatorname{det} ( {{\Delta _{ ( {\bar{z},\tau ,p} )}} ( \lambda )} ) = 0\) are called characteristic roots. (A2) indicates that 0 is not an eigenvalue of the stationary solution.

Obviously, the characteristic matrix \({\Delta _{ ( {z,\tau ,p} )}} ( \lambda )\) is continuous with respect to \(( {\tau , p, \lambda } ) \in {B_{{\xi _{0}}}} ( {{\tau _{j}}, {{2\pi } / {{\omega _{0}}}}} ) \times C\). If the stationary solution \(( {{{\bar{z}}_{0}}, {\tau _{0}}, {p_{0}}} )\) has eigenvalue with the form \(\mathrm{{i}}m ( {{{2 \pi } / {{p_{0}}}}} )\) with m an integer, we say it is a center. If in some neighborhood of \(( {{{\bar{z}} _{0}}, {\tau _{0}}, {p_{0}}} )\) it is the only center, then we say it is an isolated center.

From (12), we have

By the discussion in the previous section, we know \(( {z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, {2\pi } / {{\omega _{0}}} )\), \(j = 0,1,2, \ldots \) , are isolated centers. There exist \(\xi >0\), \(\zeta >0\), and a smooth function \(\lambda : ( {{\tau _{j}} - \zeta , {\tau _{j}} + \zeta } ) \to C\) such that, for any \(\tau \in [\tau _{j}-\zeta ,\tau _{j}+\zeta ]\), \(\operatorname{det} ( \Delta _{ ( {z^{*} },\tau ,{2\pi } / {{\omega _{0}}} )} ( {\lambda ( \tau )} ) ) = 0\), \(\vert {\lambda ( \tau ) - \mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}} \vert < \xi \), \(\lambda ( {{\tau _{j}}} ) = \mathrm{{i}}{\omega _{0}}\), and \(\operatorname{Re} \frac{\mathrm{d}\lambda }{\mathrm{d}\tau } |_{\tau = \tau _{j}} > 0\).

For \(\xi > 0\), define

then on

obviously we have

-

(A4)

\(\operatorname{det} ( {{\Delta _{ ( {{z^{*} },\tau ,p} )}} ( {v + \mathrm{{i}}\frac{{2\pi }}{p}} )} ) = 0\) if and only if \(v=0\), \(\tau =\tau _{j}\), and \(p = \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}\), \(j = 0,1,2, \ldots \) .

Furthermore, we define

From (A4), we know \({H^{+} } ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{ {2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} ) \ne 0\) on \(\partial {\varOmega _{\xi ,\frac{ {2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}}}\). The first cross number is

Write

and

Denote by \(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) the connected component of \(( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) in Σ.

To obtain the global continuation of Hopf bifurcation, we need the following result.

Lemma 6

(Wu [9])

About the connected component \(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\), we have that at least one of the following two results holds true:

-

(a)

\(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) is unbounded.

-

(b)

The projection of \(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{ {2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) onto \(X\times R_{+}\) is finite and

$$ {\varSigma _{ ( { ( {\bar{z},\bar{\tau }.\bar{p}} ) \in C ( {{z^{*} },{\tau _{j}},\frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} ) \cap N} )}}\gamma ( {\bar{z},\bar{\tau },\bar{p}} ) = 0. $$

In fact, we always have

because the cross number of any center is −1. Thus, the component \(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) through \(( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{ {{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) is nonempty and unbounded.

Lemma 7

For every center \(( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{ {{\omega _{0}}}}} )\), \(j = 0,1,2 \ldots \) , the component \(C ( {{z^{*} }, {\tau _{j}}, \frac{{2\pi }}{{{\omega _{0}}}}} )\) is unbounded.

3.2 Global existence of periodic solution

Lemma 8

The solution of (1) through nonnegative initial functions is always nonnegative.

Proof

The first equation of (1) means

which indicates \(x(t)\geq 0\) if \(x(0)\geq 0\). Similarly, we have \(y(t)\geq 0\). Suppose that there exists \(t_{0}>0\) such that \(s(t)>0\) for \(t< t_{0}\) and \(s(t_{0})=0\), then

which is a contradiction. □

In the coming part, we shall prove that system (1) has no nonconstant τ-period solution. We first make the following assumptions:

where

and

For readers’ convenience, we state the high-dimensional Bendixson theorem [11] as follows.

Lemma 9

(Li and Muldowney [11])

Suppose that one of

holds on \(\mathrm{R}^{n}\) where μ is a Lozinskiı̌ measure corresponding to an absolute norm \(|\cdot |\) on \(\mathrm{R}^{N}\), \(N= (^{n}_{2} )\). Then no simple closed rectifiable curve in \(\mathrm{R}^{n}\) is invariant with respect to \(d x /dt=f(x)\).

Lemma 10

If (H2) holds true, then system (1) has no nontrivial τ-period solution.

Proof

Suppose that (1) has a nontrivial τ-period solution, which is equivalent to the following system having a nonconstant periodic solution:

Denote \(x = { ( {{x_{1}}, {x_{2}}, {x_{3}}} )^{ \mathrm{T}}}\) and

then we know

In fact, the compound matrix of \({{\partial f} / {\partial x}}\) is

where

and

Recalling Lemma 7, the conclusion follows from Lemma 9. □

Theorem 4

Suppose (H1) and (H2) hold true, then we have the following conclusions:

-

(1)

The bifurcating periodic solutions from \(\tau _{0}\) fulfill the trichotomy

-

(a)

they exist for all \(\tau >\tau _{0}\);

-

(b)

they have amplitude tending to infinity;

-

(c)

they have period tending to infinity.

-

(a)

-

(2)

The bifurcating periodic solutions from \(\tau _{j},j=1,2, \ldots \) , fulfill the dichotomy

-

(a)

they exist for all \(\tau >\tau _{j}\);

-

(b)

they have amplitude tending to infinity.

-

(a)

4 Simulation

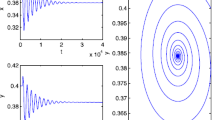

In this section, we will perform a group of simulations as an example to illustrate the theoretical results given in the previous sections. From [5], we first fix \(r=0.1\), \(\theta =5\), \(e=1\), \(\gamma =1\), \(\psi =5\), \(\epsilon =0.1\), \(\eta =0.1\), \(\delta =0.1\), \(K=0.2\), \(i=0.255\). Thus, the unique positive equilibrium \(E^{\ast }\) is \((0.0164,0.2336,0.0229)\). It is not difficult to verify that these parameters fulfill assumptions (H1) and (H2). Thus we obtain a sequence of Hopf bifurcation values \(\tau _{0}=23.1416\) and \(\tau _{k}=\tau _{0}+\frac{2k\pi }{\omega _{0}}\) with \(\omega _{0}=0.0232\). By Theorems 2 and 3, we know that \(E^{\ast }\) is asymptotically stable for \(\tau <\tau _{0}\) and stable Hopf bifurcating periodic solutions exist when \(\tau >\tau _{0}\). These results are shown in Fig. 2, where stable equilibrium and stable periodic oscillations are simulated.

Solutions of system (1) for (a) \(\tau =0\), (b) \(\tau =20\), (c) \(\tau =30\), and (d) \(\tau =35\)

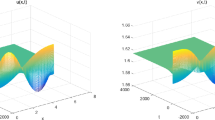

According to the global Hopf bifurcation results in Sect. 3, we give simulation by DDE-Biftool and the results are given in Fig. 3. We find that the bifurcating periodic solutions from \(\tau _{1}\) exist for any \(\tau >\tau _{1}\). However, the branch from \(\tau _{0}\) has amplitude tending to infinity. These simulations verify the unboundedness of Hopf branches established in Theorem 4.

To discuss the effect of the subsidy in model (1), we calculate the first Hopf bifurcation point as a function of the rate at which the subsidy appears, i.e., the function \(\tau _{0}(i)\) shown in Fig. 4. We find that increasing subsidies supplement would postpone the occurrence of Hopf bifurcation and lead to a larger stable interval of the positive equilibrium.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, the stability of positive equilibrium in a predator-prey model with time delay τ and subsidies and the existence of local Hopf bifurcations at the positive equilibrium were obtained. By employing the center manifold theorem and normal form theory, we obtained the properties of Hopf bifurcations including the direction of Hopf bifurcation and the stability of bifurcating periodic solutions. We further considered the global continuation of local Hopf bifurcations and obtained the global existence of periodic solutions. Usually, the conversion delay induces Hopf bifurcation and destabilizes the equilibrium, such as reported by [7]. Our theoretical findings suggest that incorporating food subsidy into a prey-predator model leads to a large stable interval of the coexistence equilibrium.

References

Lotka, A.J.: Element of Physical Biology. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore (1925)

Volterra, V.: Fluctuations in the abundance of a species considered mathematically. Nature 118(2972), 558–560 (1926)

Xiao, D., Ruan, S.: Multiple bifurcation in a delayed predator-prey system with nonmonotonic functional response. J. Differ. Equ. 176(2), 494–510 (2001)

Martin, A., Ruan, S.: Predator-prey model with delay and prey harvesting. J. Math. Biol. 43(3), 247–267 (2001)

Nevai, A.L., Gorder, R.A.V.: Effect of resource subsidies on predator-prey population dynamics: a mathematical model. J. Biol. Dyn. 6(2), 891–922 (2012)

Nindjin, A.F., Tia, K.T., Okou, H., Tetchi, A.: Stability of a diffusive predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type II schemes and time-delay in two dimensions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 177 (2018)

Peng, M., Hopf, Z.Z.: Bifurcation analysis in a predator-prey model with two time delays and stage structure for the prey. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 251 (2018)

Hassard, B.D., Kazarinoff, N.D., Wan, Y.H.: Theory and Applications of Hopf Bifurcation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1981)

Wu, J.: Symmetric functional differential equation and neural networks with memory. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 350(12), 4799–4838 (1998)

Wei, J., Li, M.Y.: Global existence of periodic solutions in a tri-neuron network model with delays. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 198, 106–119 (2004)

Li, Y., Muldowney, J.S.: On Bendixson’s criterion. J. Differ. Equ. 106, 27–39 (1993)

Engelborghs, K., Luzyanina, T., Samaey, G.: DDE-BIFTOOL v. 2.00: a Matlab package for bifurcation analysis of delay differential equations. Technical Report TW-330, Department of Computer Science, K.U. Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (2001)

Engelborghs, K., Luzyanina, T., Roose, D.: Numerical bifurcation analysis of delay differential equations using DDE-BIFTOOL. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 28, 1–21 (2002)

Ruan, S., Wei, J.: On the zeros of transcendental functions with applications to stability of delay differential equations with two delays. Dyn. Contin. Discrete Impuls. Syst., Ser. A Math. Anal. 10, 863–874 (2003)

Ruan, S., Wei, J.: On the zeros of a third degree exponential polynomial with applications to a delayed model for the control of testosterone secretion. IMA J. Math. Appl. Med. Biol. 18, 41–52 (2001)

Wiggins, S.: Introduction to Applied Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Chaos. Springer, New York (1980)

Hale, J., Verduyn Lunel, S.: Introduction to Functional Differential Equations. Springer, New York (1993)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the editors and the reviewers for the helpful comments.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research, including the study of the model, mathematical analysis, and interpretation of data, is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11701120).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YG wrote the paper and performed simulations. NJ performed calculations. BN constructed the mathematical model and performed calculations. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, we give the complete calculations about \(g_{ij}\) in Eq. (10). In fact

where

On the other hand, on the center manifold \(C_{0}\), w satisfies

and we have

Because \({u_{t}} = y ( {t + \theta } ) = w ( {z, \bar{z},\theta } ) + z q + \bar{z} \bar{q}\), so we have

that is,

Furthermore, we have

Thus \({f_{0}} ( {z,\bar{z}} )\) can be written as

where

Since \({\bar{q}^{*} } ( 0 ) = \bar{D}{ ( {1,{{\bar{ \alpha }}^{*} },{{\bar{\beta }}^{*} }} )^{\mathrm{T}}}\), we have

with

To calculate \(g_{21}\), we need to know the center manifold functions \(w_{20}(\theta )\) and \(w_{11}(\theta )\) for \(\theta \in [ { - {\tau _{0}},0} )\). In fact, we have

Thus

In fact

then we obtain

and

with \({E_{1}} = { ( {E_{1}^{ ( 1 )},E_{1}^{ ( 2 )},E_{1}^{ ( 2 )}} )^{\mathrm{T}}}\), \({E_{2}} = { ( {E_{2}^{ ( 1 )},E_{2}^{ ( 2 )},E _{2}^{ ( 3 )}} )^{\mathrm{T}}}\) are all three-dimensional vectors. In \(H ( {z,\bar{z},\theta } )\), let \(\theta =0\), then we have

This leads to

and

From the definition of A, we have

and

This indicates

and

The equation

is actually a linear equation

Thus \(E_{1}\) can be solved by

Similarly, we have

So far, we have obtained the explicit formulas which determine \(g_{20}\), \(g_{11}\), \(g_{02}\), and \(g_{21}\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Ji, N. & Niu, B. Hopf bifurcation analysis in a predator–prey model with time delay and food subsidies. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 99 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2050-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2050-3