Abstract

We study the basic dynamical features of a stochastic SIR epidemic model incorporating media coverage. Firstly, we discuss the positivity and boundedness of solutions of the model within deterministic environment and then investigate the asymptotical stability and global stability of equilibria of deterministic model. Secondly, we show that the stochastic model has a unique global positive solution and that this solution oscillates around the equilibria of the deterministic model under certain conditions. Finally, we give some numerical simulations to illustrate our analytical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Mathematical models plays an important role in the study of epidemiology, which provides understanding of the underlying mechanisms that influence the spread of disease, and in the process, it suggests control strategies. Various epidemic models have been proposed and explored extensively, and great progress has been achieved in the studies of disease control and prevention (see, e.g., [1–4]).

For establishing a mathematical model of disease transmission with the population under study being divided into compartments and with assumptions about the nature and time rate of transfer from one compartment to another, we can formulate our descriptions as compartmental models. One of the most fundamental compartment models is the SIR model [5]. This model classifies individuals to be susceptible, infectious, or removed and permanently immune. Let \(S(t)\) be the number of susceptible individuals, \(I(t)\) the number of infective individuals, and \(R(t)\) the number of removed individuals at time t, respectively. A general SIR epidemic model can be formulated as

where \(\Lambda>0\) is the recruitment rate of the population, \(\mu>0\) is the natural death rate of the population, and \(\gamma>0\) is the natural recovery rate of the infective individuals. The transmission of the infection is governed by the incidence rate \(g(I)S\), and \(g(I)\) is called the infection force.

In real life, the incidence rate \(g(I)S\) may be affected by many factors, such as media coverage, density of population, and life style. Especially, media coverage plays an important role in helping both the government authority make interventions to contain the disease and people response to the disease [6, 7]. Recently, many mathematical models have been proposed to investigate the impact of media coverage on the transmission dynamics of infectious diseases. Especially, Cui et al. [8], Tchuenche et al. [9], and Sun et al. [10] incorporated a nonlinear function of the number of infective individuals in their transmission term to investigate the effects of media coverage on the transmission dynamics:

where \(\beta_{1}>0\) is the contact rate before media alert; the terms \(\beta_{2}I/(m+I)\) measure the effect of reduction of the contact rate when infectious individuals are reported in the media. Because the coverage report cannot prevent disease from spreading completely, we have \(\beta_{1}\geqslant\beta_{2}>0\). The half-saturation constant \(m>0\) reflects the impact of media coverage on the contact transmission. The function \(I/(m+I)\) is a continuous bounded function that takes into account disease saturation or psychological effects [10]. Hence, considering the effects of media coverage on the transmission dynamics, model (1.1) can be modified as follows:

As is known to us, real life is full of randomness and stochasticity, so it is important whether or not the long-time behavior of the solution for deterministic dynamics system can be changed by stochastic perturbations. In this paper, following the idea of [11–13], we introduce a random noise to model (1.3). Following the approach used in [14, 15], for Δt small, it is appropriate to model \(X(t)= (S(t), I(t), R(t))^{T}\) as a Markov process with the following specifications:

and

More formally, we consider the following stochastic system:

Here we assume that \(B_{i}(t)\) (\(i=1,2,3\)) are independent Brownian motions and \(\sigma_{i}\) (\(i=1,2,3\)) are the coefficients of the effects of environmental stochastic perturbations on \(S(t)\), \(I(t)\), and \(R(t)\).

In the following, unless otherwise specified, we assume that \((\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \{\mathcal{F}_{t} \}_{t\geqslant0}, P)\) is a complete probability space with filtration \(\{\mathcal{F}_{t} \}_{t\geqslant0}\) satisfying the usual conditions (i.e., it is increasing and right continuous, and \(\mathcal{F}_{0}\) contains all P-null sets). Let \(B_{i}(t)\), \(i=1,2,3\), be Brownian motions defined on this probability space. Also, let \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}=\{\mathbf{x}\in\mathbb{R}^{3}, x_{i}>0 \mbox{ for all } 1\leqslant i \leqslant3 \}\) and \(\mathbf {x}(t)=(S(t), I(t), R(t))^{T}\).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we first show the positivity and boundedness of the deterministic model (1.3); the existence and stability of equilibria of model (1.3) is also investigated in this section. In Section 3, we first study the existence of the global positive solution of the stochastic model (1.4), and then, we investigate the asymptotic behavior around the equilibria of model (1.3). In Section 4, we give some numerical simulations to support the theoretical prediction. In Section 5, a brief discussion is given.

2 Deterministic model

In this section, we first discuss some basic dynamical properties of the deterministic model (1.3), which is subjected to positive initial conditions

2.1 Positivity and boundedness

In this subsection, we study the positivity and boundedness of solutions of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1).

Theorem 2.1

Solutions of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1) are positive for all \(t \geqslant0\).

Proof

Let \((S(t),I(t),R(t))\) be a solution of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1). Let us consider \(I(t)\) for \(t \geqslant 0\). It follows from the second equation of system (1.3) that

From the initial condition (2.1) we have \(I(t)>0\) for \(t \geqslant0\). Then, from the third equation of system (1.3) we have

A comparison argument shows that

From the initial condition (2.1) we have \(R(t)>0\) for \(t \geqslant0\).

Next, we prove that \(S(t)\) is positive. Assume the contrary; then let \(t_{1}\) be the first time such that \(S(t_{1})=0\). By the first equation of (1.3) we have

This means that \(S(t)<0\) for \(t\in(t_{1}-\epsilon, t_{1})\), where ϵ is an arbitrarily small positive constant. This leads to a contradiction. It follows that \(S(t)\) is always positive for \(t \geqslant0\). This ends the proof. □

Theorem 2.2

Solutions of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1) are ultimately bounded.

Proof

From Theorem 2.1, solutions of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1) are positive for all \(t \geqslant0\). Let \(N(t)= S(t)+I(t)+R(t)\). From (1.3) we have

Therefore, \(N(t)<\frac{\Lambda}{\mu} +\epsilon\) for all large t, where ϵ is an arbitrarily small positive constant. Thus, \(S(t),I(t),R(t)\) are ultimately bounded. □

2.2 Equilibria and their existence

By the next generation method in [16] the basic reproduction number for model (1.3) is

Irrespective of the parameter values, system (1.3) always possesses a disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}(\frac{\Lambda}{d},0,0)\). We next discuss the existence of endemic equilibrium. Suppose that \(E^{*}(S^{*},I^{*},R^{*})\) is an endemic equilibrium. Then \((S^{*},I^{*},R^{*})\) satisfies

It follows that

and \(I^{*}\) determined by

where \(g(I)=\beta_{1}-\frac{\beta_{2}I}{m+I}\). Equation (2.6) is equivalent to

Denote

From Theorem 2.1 and (2.2) we have \(I^{*}\in[0,\frac{\Lambda}{\mu }]\). From (2.8) we have

Hence, for \(R_{0}>1\), we have

For \(R_{0}<1\), we have

Moreover, we can compute that

Note that \(\beta_{1} \geqslant\beta_{2}>0\). From (2.12) we can easily prove that \(G(I)\) is decreasing and \(H(I)\) is increasing. Hence, from (2.10)-(2.12) we can verify that if \(R_{0}>1\), then the two curves \(G(I)\) and \(H(I)\) have only one positive intersection in \([0,\frac{\Lambda}{\mu}]\), which gives only one endemic equilibrium. However, if \(R_{0}<1\), then it follows that the two curves \(G(I)\) and \(H(I)\) have no intersection in \([0,+\infty)\), which implies that there is no endemic equilibria.

From the discussion above we obtain the following:

Theorem 2.3

If \(R_{0}<1\), then system (1.3) has no endemic equilibria. If \(R_{0}>1\), then system (1.3) has only one endemic equilibrium.

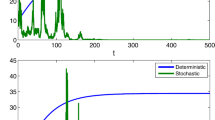

Figure 1 shows two possible cases of the intersection of the curves \(G(I)\) and \(H(I)\). Figure 1(a) shows that the two curves have no intersection with parameter I varying when \(R_{0}<1\). Figure 1(b) shows that the two curves have only one intersection with parameter I varying when \(R_{0}>1\).

Two possible cases of the intersection of the curves \(\pmb{G(I)}\) and \(\pmb{H(I)}\) indicating the existence of positive equilibria. (a) \(\Lambda=15\), \(\beta_{1}=0.0008\), \(\beta_{2}=0.0006\), \(m=30\), \(\mu=0.05\), \(\gamma=0.2 \). \(R_{0}=0.96<1\). (b) \(\Lambda=15\), \(\beta_{1}=0.002\), \(\beta_{2}=0.0018\), \(m=30\), \(\mu=0.05\), \(\gamma=0.2 \). \(R_{0}=2.4>1\).

2.3 Stability of equilibria

In this subsection, by analyzing the corresponding characteristic equations we discuss the local stability of a disease-free equilibrium and endemic equilibrium of system (1.3), respectively.

The characteristic equation of system (1.3) at \(E_{0}\) is

which is equivalent to

It is easy to see that, when \(R_{0}<1\), (2.14) has three negative roots and, when \(R_{0}>1\), (2.14) always has one positive root. Thus, we have the following:

Theorem 2.4

-

(i)

The disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}\) of (1.3) is locally asymptotically stable if \(R_{0}<1\).

-

(ii)

The disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}\) of (1.3) is unstable if \(R_{0}>1\).

Next, we discuss the global stability of \(E_{0}\). It is easy to prove the following lemma.

Lemma 2.1

The plane \(S+I+R= \frac{\Lambda}{\mu}\) is an invariant manifold of system (1.3), which is globally attractive in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\).

Theorem 2.5

If \(R_{0}<1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}\) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof

Let \((S(t),I(t),R(t))\) be any positive solution of system (1.3) with initial condition (2.1).

If \(R_{0}<1\), then choose \(\epsilon>0\) sufficiently small to satisfy

It follows from the first equation of system (1.3) that

By comparison we obtain that

Hence, for \(\epsilon>0\) sufficiently small to satisfy (2.15), there is \(T_{1}>0\) such that if \(t>T_{1}\), then \(S(t)<\frac{\Lambda }{\mu} +\epsilon\).

For \(\epsilon>0\) sufficiently small to satisfy (2.15), it follows from the second equation of system (1.3) that, for \(t>T_{1}\),

From (2.15) a comparison argument shows that

Hence, for \(\epsilon>0\) sufficiently small to satisfy (2.15), there is \(T_{2}>T_{1}\) such that if \(t>T_{2}\), then \(I(t)<\epsilon\).

From the first equation of system (1.3), for \(t>T_{2}\), we have

By comparison it follows that

Letting \(\epsilon\rightarrow0\), we derive that

Note that if \(R_{0}<1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable. Then, combining this with Lemma 2.1, we conclude that if \(R_{0}<1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}(\Lambda/\mu, 0, 0)\) is globally asymptotically stable. □

In the following, we suppose that \(R_{0}>1\) and \(E^{*}\) is an endemic equilibrium satisfying Eqs. (2.4)-(2.6).

Theorem 2.6

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the endemic equilibrium \(E^{*}\) is globally stable in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\).

Proof

Noting that the variable R only occurs in the third equation of system (1.3), by Lemma 2.1 it suffices to investigate the subsystem

Taking the Dulac function \(D=\frac{1}{S(t)I(t)}\), we have

From the Bendixson-Dulac theorem [17] we know that system (2.18) has no limit cycle in \(\mathbb{R}^{2}_{+}\). Hence, system (1.3) has no limit cycle in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\).

When \(R_{0}>1\), by Theorem 2.1, \(E_{0}\) is a hyperbolic unstable saddle point and repels solutions in its neighborhood. Due to the hyperbolicity of \(E_{0}\), it is not part of any cycle chain in \(\mathbb {R}^{3}_{+}\). Thus, every bounded forward orbit of (1.3) in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) converges to the unique endemic equilibrium \(E^{*}\). Therefore, \(E^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable. The proof is complete. □

3 Stochastic model

In this section, we first show that the solution of system (1.4) is global and nonnegative. As we know, in order for a stochastic differential equation to have a unique global (i.e., without explosion in finite time) solution for any given initial value, the coefficients of the equation are generally required to satisfy the linear growth condition and local Lipschitz condition [18]. However, the coefficients of Eq. (1.4) do not satisfy the linear growth condition, though they are locally Lipschitz continuous, so the solution of Eq. (1.4) may explode in finite time [18]. Using the Lyapunov analysis method (mentioned in [18]), it is easy to show that the solution of Eq. (1.4) is positive and global.

Theorem 3.1

For any given initial value \((S(0),I(0),R(0))\in\mathbb {R}^{3}_{+}\), there is a unique positive solution \((S(t),I(t),R(t))\) of model (1.4) on \(t\geqslant0\), and the solution remains in \(\mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) with probability 1, namely \((S(t),I(t),R(t)) \in \mathbb{R}^{3}_{+}\) for all \(t\geqslant0\) almost surely.

From the discussion of Section 2, for the deterministic model (1.3), there is a disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}=(\frac{\Lambda }{d},0,0)\), which is globally stable if \(R_{0}=\frac{ \beta_{1}\Lambda }{\mu(\mu+\gamma)}<1\). However, for the stochastic model (1.4), \(E_{0}=(\frac{\Lambda}{d},0,0)\) is no longer a disease-free equilibrium. In this subsection, we investigate the asymptotic behavior around \(E_{0}\).

Theorem 3.2

Suppose that \(R_{0}=\frac{ \beta_{1}\Lambda}{\mu(\mu+\gamma)}<1\) and

Then, for any given initial value \((S(0),I(0),R(0))\in\mathbb {R}^{3}_{+}\), the solution of model (1.4) has the property

where

Proof

Let \(x=S-\frac{\Lambda}{\mu}\), \(y=I\), \(z=R\). Then system (1.4) can be rewritten as

By Theorem 3.1 we have \(x=S-\frac{\Lambda}{\mu}> -\frac{\Lambda}{\mu}\), \(y>0\), \(z>0\). Define the function

where \(c_{1}\) and \(c_{2}\) are positive constants to be determined later. Then the function V is positive definite. Applying Itô’s formula, we obtain

where

We can choose \(c_{1}=\frac{2(2\mu+\gamma)}{\beta_{1}}>0\) such that \(c_{1}\beta_{1}-2(2\mu+\gamma)=0\), and noting that \(R_{0}<1\), we can choose \(c_{2}>0\) such that \(c_{2}\gamma-c_{1}\beta_{1}\frac{\Lambda }{\mu} ( \frac{1}{R_{0}}-1 )=0\); then \(c_{2}=\frac{2\Lambda (2\mu+\gamma)(1-R_{0})}{\gamma\mu R_{0}} \). Thus, we obtain

Therefore,

Integrating both sides of (3.4) from 0 to t and then taking expectation yield

which implies

Therefore,

from which it follows that

Letting

we have

This ends the proof. □

Remark 3.1

From Theorem 3.2 we can conclude that if \(R_{0}<1\) and condition (3.1) holds, then the solution of Eq. (1.4) will fluctuate around the disease-free equilibrium of Eq. (1.3).

3.1 Asymptotic behavior around the endemic equilibrium of the deterministic model

In this subsection, we assume that \(R_{0} >1\). Then model (1.3) has a single endemic equilibrium \(E^{*}\), but for model (1.4), \(E^{*}\) is not an endemic equilibrium. Similarly, we also expect to find out whether or not the solution goes around \(E^{*}\). The following result gives a positive answer.

Theorem 3.3

If \(R_{0}=\frac{ \beta_{1}\Lambda}{\mu(\mu+\gamma )}>1\) and

then for any given initial value \((S(0),I(0),R(0))\in\mathbb {R}^{3}_{+}\), the solution of model (1.4) has the property

where

Proof

Define the \(\mathcal{C}^{2}\)-function \(V: \mathbb{R}^{2}_{+}\rightarrow\bar{\mathbb {R}}_{+}\) by

where \(a>0\) and \(p>0\) are constants to be determined later. For simplicity, we divide (3.7) into two functions: \(V(x)=V_{1}(x) +V_{2}(x)\), where

Applying Itô’s formula, we obtain

and

where

and

Choose \(a=\frac{2\mu+\gamma}{\beta}>0\) such that \(a\beta-(2\mu+\gamma )=0\), where \(\beta=\beta_{1}-\frac{\beta_{2}I^{*} }{m+I^{*} }\). Noticing that \((I-I^{*})\) and \([ \frac{\beta_{2}I }{m+I }- \frac {\beta_{2}I^{*} }{m+I^{*} } ]\) have the same sign, it follows from (3.8) that

Taking (3.9) and (3.10) together, we have

Note that \(\sigma_{2}^{2}<2(\mu+\gamma)\). Then we can choose \(0< p<\frac {2\mu(\mu+\gamma)-\mu\sigma_{2}^{2}}{\gamma^{2}}\), and the condition (3.6) implies that

Thus,

Integrating both sides of (3.12) from 0 to t, taking expectations, and considering inequality (3.11), we obtain

where

Thus, we have

Dividing both sides of (3.14) by t and letting \(t\rightarrow \infty\), we have

Let \(K_{2}=\min \{ \mu-\frac{1}{2}\sigma_{1}^{2}, \mu+\gamma -\frac{1}{2}\sigma_{2}^{2} -\frac{p\gamma^{2}}{2\mu}, \frac{p}{2}(\mu -\sigma_{3}^{2}) \} \). Then from (3.15) we have

This ends the proof. □

Remark 3.2

From Theorem 3.3 we can conclude that if \(R_{0}>1\) and condition (3.6) holds, then the solution of Eq. (1.4) fluctuates around the endemic equilibrium of Eq. (1.3).

4 Numerical simulations

In this section, we provide numerical simulation results to substantiate the analytical findings for the stochastic model system reported in the previous sections. Using Milstein’s higher-order method [19], we get the discretization equation

where the time increment \(\Delta t>0\), and \(\varepsilon_{1k,i}\), \(\varepsilon_{2k,i}\), \(\varepsilon_{3k,i}\), \(k=1,2,3\), are \(N(0,1)\)-distributed independent random variables.

Example 4.1

In this case, we set \(\Lambda=15\), \(\beta_{1}=0.0008\), \(\beta_{2}=0.0006\), \(m=30\), \(\mu=0.05\), \(\gamma=0.2 \), where ‘year’ is used as the unit of time [20].

From Eq. (2.3) we compute \(R_{0}=0.96<1\). From the discussion of Section 2 we know that system (1.3) has only one disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}(300,0,0)\), which is globally asymptotically stable.

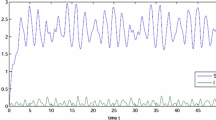

We now consider the environment noise in (1.3) and study the dynamics of the resulting system (1.4). By Theorem 3.2 the expectations of \(S(t)\), \(I(t)\), \(R(t)\) are bounded in time average when condition (3.1) is also satisfied. Obviously, the boundedness is proportional to \(\sigma_{1}\); moreover, the smaller \(\sigma_{1}\), the less the boundedness. The following numerical simulations of the strong solution of (1.4) confirm the results we have shown. Figure 2(a), (b) shows that the curves of system (1.4) always fluctuate around the curves of system (1.3) with different intensities of white noise. Moreover, comparison of Figure 2(a) and Figure 2(b) suggest that the fluctuations reduce as the noise level decreases.

Solutions of deterministic model ( 1.3 ) (blue) and stochastic model ( 1.4 ) (red) with \(\pmb{\Lambda=15}\) , \(\pmb{\beta _{1}=0.0008}\) , \(\pmb{\beta_{2}=0.0006}\) , \(\pmb{m=30}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\gamma=0.2 }\) . (a) \(\sigma_{1}=0.1\), \(\sigma_{2}=0.05\), \(\sigma_{3}=0.05\). (b) \(\sigma_{1}=0.05\), \(\sigma_{2}=0.02\), \(\sigma_{3}=0.02\).

Example 4.2

In this case, we set \(\Lambda=15\), \(\beta_{1}=0.002\), \(\beta_{2}=0.0018\), \(m=30\), \(\mu=0.05\), \(\gamma=0.2 \), where ‘year’ is used as the unit of time [20].

From Eq. (2.3) we compute \(R_{0}=2.4>1\). From the discussion of Section 2 we know that system (1.3) has an unstable disease-free equilibrium \(E_{0}(300,0,0)\) and a globally asymptotically stable endemic equilibrium \(E^{*}=(197.1728, 20.5654, 82.2617)\).

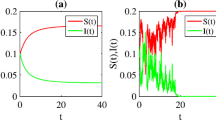

We next consider the environment noise in (1.3) and study the dynamics of the resulting system (1.4). By Theorem 3.3 the expectations of \(S(t)\), \(I(t)\), \(R(t)\) are bounded in time average when condition (3.6) is also satisfied. Similarly as before, the solution of (1.4) also fluctuates around the solution of (1.3), which supports the results of Theorem 3.3. In detail, in Figure 3(a) and Figure 3(b), the parameters are the same except for the decreasing intensities. From Figure 3(a), (b) we can also see that the fluctuation is weaker with intensities decreasing.

Solutions of deterministic model ( 1.3 ) (blue) and stochastic model ( 1.4 ) (red) with \(\pmb{\Lambda=15}\) , \(\pmb{\beta _{1}=0.002}\) , \(\pmb{\beta_{2}=0.0018}\) , \(\pmb{m=30}\) , \(\pmb{\mu=0.05}\) , \(\pmb{\gamma=0.2 }\) . (a) \(\sigma_{1}=0.1\), \(\sigma_{2}=0.05\), \(\sigma_{3}=0.05\). (b) \(\sigma_{1}=0.02\), \(\sigma_{2}=0.02\), \(\sigma_{3}=0.01\).

5 Discussion

In this paper, we proposed a stochastic SIR epidemic model incorporating media coverage. We first investigated the positivity and boundedness of the solution of model (1.3). We showed that the solution of model (1.3) with the initial condition (2.1) is positive and bounded. Our results also show that, when \(R_{0}<1\), model (1.3) has only one disease-free equilibrium and, when \(R_{0}>1\), model (1.3) has a disease-free equilibrium and an endemic equilibrium. Then, we studied the stability of the disease-free and endemic equilibria. Our results show that the disease-free equilibrium is globally stable when the basic reproduction number \(R_{0}<1\) and is unstable when \(R_{0}>1\). This result shows that media coverage cannot change the basic feature of the SIR epidemic model (1.1) [21]. That is to say, disease eventually disappears when the basic reproduction number \(R_{0}<1\); however, the epidemic eventually becomes an endemic disease when \(R_{0}>1\).

Section 3 deals with the stochastic differential equations; by using suitable Lyapunov functions we show that the solution of the stochastic model is positive and global, and this solution oscillates around the equilibria of the deterministic model under certain conditions. That is to say, if the effects of environmental stochastic perturbations are smaller enough than the natural death rate, then the solution of the stochastic model (1.4) oscillates around the disease-free equilibrium when \(R_{0}<1\); however, the solution of the stochastic model (1.4) oscillates around the endemic equilibrium when \(R_{0}>1\). Moreover, the numerical results also suggest that the fluctuations reduce as the noise level decreases.

References

Anderson, R, May, R: Population biology of infectious diseases: part I. Nature 280, 361-367 (1979)

Hethcote, HW: The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 42, 599-653 (2000)

Gao, D, Ruan, S: An SIS patch model with variable transmission coefficients. Math. Biosci. 232, 110-115 (2011)

Arguin, PM, Navin, AW, Steele, SF, Weld, LH, Kozarsky, PE: Health communication during SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 377-380 (2004)

Manfredi, P, d’Onofrio, A: Modeling the Interplay Between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases. Springer, New York (2013)

Liu, Y, Cui, J: The impact of media coverage on the dynamics of infectious disease. Int. J. Biomath. 1, 65-74 (2008)

Xiao, Y, Zhao, T, Tang, S: Dynamics of an infectious diseases with media/psychology induced non-smooth incidence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 10, 445-461 (2013)

Cui, J, Sun, Y, Zhu, H: The impact of media on the control of infectious diseases. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ. 20, 31-53 (2008)

Tchuenche, JM, Dube, N, Bhunu, CP, Smith, RJ, Bauch, CT: The impact of media coverage on the transmission dynamics of human influenza. BMC Public Health 11, Article S5 (2011)

Sun, C, Yang, W, Arino, J, Khan, K: Effect of media-induced social distancing on disease transmission in a two patch setting. Math. Biosci. 230, 87-95 (2011)

Rudnicki, R: Long-time behaviour of a stochastic prey-predator model. Stoch. Process. Appl. 108, 93-107 (2003)

Jiang, D, Yu, J, Ji, C, Shi, N: Asymptotic behavior of global positive solution to a stochastic SIR model. Math. Comput. Model. 54, 221-232 (2011)

Lin, Y, Jiang, D, Xia, P: Long-time behaviour of a stochastic SIR model. Appl. Math. Comput. 236, 1-9 (2014)

Liu, M, Bai, C: Analysis of a stochastic tri-trophic food-chain model with harvesting. J. Math. Biol. (2016). doi:10.1007/s00285-016-0970-z

Evans, SN, Ralph, PL, Schreiber, SJ, Sen, A: Stochastic population growth in spatially heterogeneous environments. J. Math. Biol. (2013). doi:10.1007/s00285-012-0514-0

Van den Driessche, P, Watmough, J: Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 180, 29-48 (2002)

Zhang, Z, Ding, T, Huang, W, Dong, Z: Qualitative Theory of Differential Equations. Am. Math. Soc., Providence (1992)

Mao, X: Stochastic Differential Equations and Applications. Horwood, Chichester (1997)

Higham, KJ: An algorithmic introduction to numerical simulation of stochastic differential equations. SIAM Rev. 43, 525-546 (2001)

Xu, R: Global stability of a delayed epidemic model with latent period and vaccination strategy. Appl. Math. Model. 36, 5293-5300 (2012)

Martcheva, M: An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology. Springer, New York (2015)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank the editors and anonymous referees for their careful reading and constructive suggestions which lead to truly significant improvement of the manuscript. This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11061016, 11461036), the Science and Technology Department of Henan Province (No. 152300410230), and the Doctoral Research Foundation of Zhoukou Normal University (No. ZKNU2014126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, M., Zhao, H. Asymptotic behavior of global positive solution to a stochastic SIR model incorporating media coverage. Adv Differ Equ 2016, 149 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0884-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0884-5