Abstract

In this article, the existence of solution for the first-order nonlinear coupled system of ordinary differential equations with nonlinear coupled boundary condition (CBC for short) is studied using a coupled lower and upper solution approach. Our method for a nonlinear coupled system with nonlinear CBC is new and it unifies the treatment of many different first-order problems. Examples are included to ensure the validity of the results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this article, we consider the following nonlinear coupled system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs for short):

subject to the nonlinear CBC

where the nonlinear functions \(f,g:[0,1]\times{R}\rightarrow{R}\) and \(h:{R}^{4}\rightarrow{R}^{2}\) are continuous.

A significant motivation factor for the study of the above system has been the applications of the nonlinear differential equations to the areas of mechanics; population dynamics; optimal control; ecology; biotechnology; harvesting; and physics [1–3]. Moreover, while dealing with nonlinear ordinary differential systems (ODSs for short) mostly authors only focus attention on the differential systems with uncoupled boundary conditions [4–6]. But, on the other hand, very little research work is available where the differential systems are coupled not only in the differential systems but also through the boundary conditions [7, 8]. Our system (1)-(2) deals with the latter case.

The other productive aspect of the article is the generalization of the classical concepts that had been discussed in [9–11]. We mean to say if \(h(x,y,z,w)=(x-z,y-w)\), then (2) implies the periodic boundary conditions (BCs for short). Also if \(h(x,y,z,w)=(x+z,y+w)\), then (2) implies the anti-periodic BCs. Definitely, in order to obtain a solution satisfying some initial or BCs and lying between a subsolution and a supersolution, we need additional conditions. For example, in the periodic case it suffices that

and in the anti-periodic case it suffices that

so to generalize the classical results (3) and (4) the concept of coupled lower and upper solution is defined, which allows us to obtain a solution in the sector \([\alpha_{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\) or \([\beta_{1},\alpha _{1} ]\times [\beta_{2},\alpha_{2} ]\) and also the inequalities (22)-(23) imply (3) and (4).

Definition 1.1

We say that a function \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2} )\in C^{1}[0,1]\times C^{1}[0,1]\) is a subsolution of (1) if

In the same way, a supersolution is a function \((\beta_{1},\beta _{2} )\in C^{1}[0,1]\times C^{1}[0,1]\) that satisfies the reversed inequalities in (5). In what follows we shall assume that \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2} )\preceq (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\), if \(\alpha_{1}(t)\leq\beta_{1}(t)\) and \(\alpha_{2}(t)\leq\beta _{2}(t)\), for all \(t\in[0,1]\) or \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2} )\succeq (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\), if \(\alpha_{1}(t)\geq\beta _{1}(t)\) and \(\alpha_{2}(t)\geq\beta_{2}(t)\), for all \(t\in[0,1]\).

For \(u,v\in C^{1}[0,1]\), we define the set

The following lemma is important for our work.

Lemma 1.2

Let \(L: C[0,1]\times C[0,1]\rightarrow C_{0}[0,1]\times C_{0}[0,1]\times{R}^{2}\) be defined by

where λ, a, b, c, and d are real constants such that

and

Then \(L^{-1}\) exists and is continuous and defined by

with

Proof

Choose

and

In the light of (8)-(11), (6) can also be written as

Differentiating (8) w.r.t. t, we have

Multiplying (13) with integrating factor \(e^{\lambda t}\), we have

then after integrating and taking the limits of integration from 0 to t, (14) becomes

\(u(0)\) can easily be determined with the help of (10) as

then

for simplicity of notation, let

Similarly along the same lines, it can easily be shown that

with

(12) can also be written as

2 Coupled lower and upper solutions

The following definition is very helpful to construct the statement of the main result (2.2), and also it covers different possibilities for the nonlinear function h.

Definition 2.1

We say that \((\alpha_{1},\alpha _{2} ), (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\in C^{1}[0,1]\times C^{1}[0,1]\) are coupled lower and upper solutions for the problem (1) and (2) if \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\) is a subsolution and \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) a supersolution for the system (1) such that

and

Theorem 2.2

Assume that \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) are coupled lower and upper solutions for the system (1)-(2). In addition, suppose that the functions

are monotone on \([\alpha_{1}(1),\beta_{1}(1)]\times[\alpha_{2}(1),\beta _{2}(1)]\), then the system (1)-(2) has at least one solution \((u,v )\in [\alpha_{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\).

Proof

Let \(\lambda>0\) and consider the modified system

with

and

and

Note that if \((u,v )\in [\alpha_{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\) is a solution of the system (24), then \((u,v)\) is a solution of the system (1)-(2).

For the sake of simplicity we divide the proof into three steps.

Step 1: We define the mappings

by

and

Clearly, N is continuous and compact by the direct application of the Arzela-Ascoli theorem. Also from Lemma 1.2 with \(a=1\), \(b=0\), \(c=1\), and \(d=0\), \(L^{-1}\) exists and is continuous.

On the other hand, solving (24) is equivalent to finding a fixed point of

Now, the Schauder fixed point theorem guarantees the existence of at least a fixed point since \(L^{-1}N\) is continuous and compact.

Step 2: It remains to show that \((u,v)\in [\alpha_{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\).

We claim that \((u,v )\preceq (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\). If \((u,v )\npreceq (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\), then \(u\npreceq\beta_{1}\) and/or \(v\npreceq\beta_{2}\). If \(u\npreceq\beta _{1}\), then there exist some \(r_{0}\in[0,1]\), such that \(u-\beta_{1}\) attains a positive maximum at \(r_{0}\in[0,1]\). We shall consider three cases.

Case 1. \(r_{0} \in(0,1]\). Then there exists \(\xi\in (0,r_{0})\), such that \(0< u(t)-\beta_{1}(t)< u(r_{0})-\beta_{1}(r_{0})\), for all \(t\in[\xi,r_{0})\). This yields a contradiction, since

Case 2. \(r_{0}=0\) and \(h_{\beta}\) is monotone nonincreasing. Then \(u(0)-\beta_{1}(0)>0\) or \(v(0)-\beta_{2}(0)>0\), and in view of (22), we have

a contradiction.

Case 3. Similarly \(h_{\beta}\) is monotone nondecreasing. We shall change the inequality (25) by \((u(0),v(0) )\preceq (\beta_{1}(0),\beta_{2}(0) )-h (\beta_{1}(0),\beta _{2}(0),\alpha_{1}(1),\alpha_{2}(1) )\) and again we get a contradiction. Consequently, \((u,v )\preceq (\beta_{1},\beta_{2} )\), for all \(t\in[0,1]\). Similarly, we can show that \((u,v )\succeq (\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2} )\), for all \(t\in[0,1]\).

Step 3: Now, it remains to show that \((u,v)\) satisfies the boundary condition (2).

For this, we claim that

If \((u(0),v(0) )-h (u(0),v(0),u(1),v(1) ) \npreceq (\beta_{1}(0),\beta_{2}(0) )\), then

If \(h_{\beta}(x,y)\) is monotone nonincreasing, then we have

a contradiction. Similarly if \(h_{\beta}(x,y)\) is monotone nondecreasing, then we get the same contradiction. Consequently, (26) holds. Hence the system of BVPs (1)-(2) has a solution \((u,v)\in [\alpha_{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\). □

Remark 2.3

If \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2} )\succeq (\beta_{1},\beta _{2} )\), then (23) is replaced by

Theorem 2.4

Assume that \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) are coupled lower and upper solutions in reverse order for the system (1)-(2). In addition, suppose that the functions

are monotone in \([\beta_{1}(0),\alpha_{1}(0) ]\times [\beta_{2}(0),\alpha_{2}(0) ]\), then the system (1)-(2) has at least one solution \((u,v )\in [\beta_{1},\alpha_{1} ]\times [\beta _{2},\alpha_{2} ]\).

Proof

The proof of Theorem 2.4 is analogous to the proof of Theorem 2.2. □

3 Examples

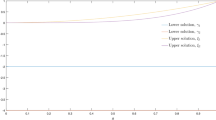

Example 3.1

Let

Let \(\alpha_{1}(t)=-2\gamma\), \(\alpha_{2}(t)=-\gamma\), and \(\beta _{1}(t)=2\gamma\), \(\beta_{2}(t)=\gamma\). It is easy to show that \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) are a subsolution and a supersolution of the system (1), respectively. Further, \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) satisfy (22)-(23). Hence by Theorem 2.2, the system of BVPs (1)-(2) has at least one solution \((u,v )\in [\alpha _{1},\beta_{1} ]\times [\alpha_{2},\beta_{2} ]\).

Example 3.2

Let

Choose \(\alpha_{1}(t)=3\gamma\), \(\alpha_{2}(t)=2\gamma\), \(\beta _{1}(t)=-3\gamma\), \(\beta_{2}(t)=-2\gamma\). We can show that \((\alpha _{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) are a subsolution and a supersolution of the system (1), respectively. Further, \((\alpha _{1},\alpha_{2})\), \((\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\) satisfy (22) and (28). Hence by Theorem 2.4, the system of BVPs (1)-(2) has at least one solution \((u,v )\in [\beta_{1},\alpha _{1} ]\times [\beta_{2},\alpha_{2} ]\).

4 Conclusion

The new existence results are established for a nonlinear ordinary coupled system with nonlinear CBCs. The developed result unifies the treatment of many first-order problems [12–15]. Examples are included to verify the theoretical results. The existence results are also discussed when the lower and upper solutions are in reverse order \((\alpha_{1},\alpha_{2})\succeq(\beta_{1},\beta_{2})\).

References

Zhang, Y: Positive solutions of singular sublinear Embden-Fowler boundary value problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 185, 215-222 (1994)

Zhang, W, Fan, M: Periodicity in a generalized ecological competition system governed by impulsive differential equations with delays. Math. Comput. Model. 39, 479-493 (2004)

Nieto, JJ: Periodic boundary value problems for first-order impulsive ordinary differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 51, 1223-1232 (2002)

Agarwal, RP, O’Regan, D: A coupled system of boundary value problems. Appl. Anal. 69, 381-385 (1998)

Cheng, C, Zhong, C: Existence of positive solutions for a second-order ordinary differential system. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 312, 14-23 (2005)

Henderson, J, Luca, R: Positive solutions for a system of second-order multi-point boundary value problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 218, 6083-6094 (2012)

Asif, NA, Khan, RA: Positive solutions to singular system with four-point coupled boundary conditions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 386, 848-861 (2012)

Wu, J: Theory and Applications of Partial Functional-Differential Equations. Applied Mathematical Sciences. Springer, New York (1996)

Lakshmikantham, V: Periodic boundary value problems of first and second order differential equations. J. Appl. Math. Simul. 2, 131-138 (1989)

Lakshmikantham, V, Leela, S: Existence and monotone method for periodic solutions of first-order differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 91, 237-243 (1983)

Nkashama, MN: A generalized upper and lower solutions method and multiplicity results for nonlinear first-order ordinary differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 140, 381-395 (1989)

Jankowski, T: Ordinary differential equations with nonlinear boundary conditions of antiperiodic type. Comput. Math. Appl. 47, 1419-1428 (2004)

Lakshmikantham, V: Periodic boundary value problems of first and second order differential equations. J. Appl. Math. Simul. 2, 131-138 (1989)

Franco, D, Nieto, JJ, O’Regan, D: Anti-periodic boundary value problem for nonlinear first order ordinary differential equations. Math. Inequal. Appl. 6, 477-485 (2003)

Wang, K: A new existence result for nonlinear first-order anti-periodic boundary value problems. Appl. Math. Lett. 21, 1149-1154 (2008)

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the referees careful reading and comments on this paper that led to the improvement of the original manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Asif, N.A., Talib, I. & Tunc, C. Existence of solution for first-order coupled system with nonlinear coupled boundary conditions. Bound Value Probl 2015, 134 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-015-0397-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-015-0397-2