Abstract

Background

Prospective registration aims to reduce bias in the conduct and reporting of research and to increase transparency. In addition, prospective registration of systematic reviews is argued to help preventing unintended duplication, thereby reducing research waste. PROSPERO was launched in 2011 as the first prospective register for systematic reviews. While it has long been the only option to prospectively register systematic reviews, recently there have been new developments. Our aim was to identify and characterize current options to prospectively register a systematic review to assist review authors in choosing a suitable register.

Methods

To identify systematic review registers, we independently performed internet searches in January 2021 using keywords related to systematic reviews and prospective registration. “Registration” was defined as the process of entering information about a planned systematic review into a database before starting the systematic review process. We collected data on the characteristics of the identified registries and contacted the responsible party of each register for verification of the data related to their registry.

Results

Overall, we identified five options to prospectively register a systematic review: PROSPERO, the Registry of Systematic Reviews/Meta-Analyses in Research Registry, and INPLASY, which are specific to systematic reviews, and the Open Science Framework Registries and protocols.io, which represent generic registers open to any study type. Detailed information on each register is presented in tables in the main text. Regarding the systematic-review-specific registries, authors have to trade-off between the costs of registration and the processing time of their registration record. All registers provide an option to search for systematic reviews already registered in the register. However, it is unclear how useful these search functions are.

Conclusion

Authors can prospectively register their systematic review in five registries, which come with different characteristics and features. The research community should discuss fair and sustainable financing models for registers that are not operated by for-profit organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

The purpose of prospective registration of systematic reviews

Prospective registration is a means to publish details about a research project before its commencement thus allowing evidence users to assess whether all steps of the research have been performed and reported as planned, or not. The overall aim is to reduce bias in the conduct and reporting of research and to increase transparency. The Declaration of Helsinki states that “[e]very research study involving human subjects must be registered in a publicly accessible database before recruitment of the first subject” [1]. In addition, prospective registration is legally required in the United States and Europe for some types of clinical trials [2, 3]. However, neither these laws nor the Declaration of Helsinki apply to the literature-based study type of systematic reviews. Nevertheless, one could argue that prospective registration is just as important for systematic reviews for they usually play an even greater role in evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice and health policy than single clinical trials [4]. In addition to reducing bias and increasing transparency, prospective registration of systematic reviews may prevent unintended duplication, thereby reducing research waste [5, 6].

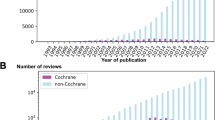

Organizations conducting or commissioning systematic reviews related to health, such as Cochrane or the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), have their own databases of ongoing and published reviews. However, these databases are restricted to systematic reviews performed within these organizations. Thus, the idea of creating an independent registry of systematic reviews was proposed in January 2010 [7]. Following the establishment of a minimum dataset for prospective registration of systematic reviews [8], PROSPERO, the first international prospective register of systematic reviews, has been launched in February 2011. Nowadays, prospective registration of systematic reviews has been widely established and it is estimated that one third of systematic reviews published in 2018 were registered in PROSPERO [9].

From the viewpoint of authors, registers for systematic reviews need two main characteristics:

-

1.

Offering the service to prospectively register a systematic review

-

2.

Providing an oversight of all registered systematic reviews, including a search function

While the first one is obvious, the second one is particularly important when it comes to reducing unintended duplication of systematic reviews. All researchers intending to perform a systematic review should first search bibliographic databases and registers for systematic reviews on the same or similar research questions to avoid conducting duplicate reviews, which is already a major problem [10, 11].

Although PROSPERO has long been the only option to prospectively register systematic reviews, there recently have been new developments. Our aim was to identify and characterize current options to prospectively register a systematic review and thereby to assist review authors in choosing a suitable register.

Scope

In this context, we define “prospective registration” as the action of entering information about a research project (here: a systematic review) into a database before its commencement. Usually, there is a pre-defined set of items the submitting authors are required to enter upon submission, such as the title, authors, aspects of the planned methods, and contact details. The depth of information is often left up to the authors, however. Prospective registration ought to be differentiated from publishing a manuscript for a protocol. Protocols are typically published as a stand-alone peer-reviewed article in a journal, as a registered report, or on a preprint server. The first two options have the advantage that the protocol manuscripts (unlike registration records and preprints) undergo peer-review which resembles a form of quality assurance. Furthermore, it can be assumed that journal publications have a high visibility as they are indexed in electronic databases.

We only considered registers for prospective registration of systematic reviews. Registers of completed systematic reviews, such as the Center on Knowledge Translation for Disability and Rehabilitation Research (KTDRR) Registry of Systematic Reviews [12], or KSR Evidence [13] are not further considered. Furthermore, we did not consider registers that are not universally open to all authors, such as the options offered by Cochrane, the Campbell Collaboration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the JBI, or the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration.

Overview of current options to prospectively register a systematic review

To identify systematic review registers, the two authors independently performed internet searches in generic search engines (Google, DuckDuckGo) using keywords related to systematic reviews and prospective registration in January 2021. Furthermore, experts from the authors’ wider research network were contacted about their knowledge of further systematic review registers. We collected data on the registries identified in the previous step and organized the data in structured tables. Categories were developed deductively by the two authors. Regular meetings were held between the authors to agree on the categories. This process was informed by relevant literature, including several works of the authors. Following data collection, we contacted the responsible party of each register in April 2021 for verification of the data we had collected with regard to their registry.

Overall, we describe five options to prospectively register a systematic review: PROSPERO, the Registry of Systematic Reviews/Meta-Analyses in Research Registry, and INPLASY, which are specific to systematic reviews, and Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries and protocols.io, which present generic registers open to any study type. OSF registries specifically focuses on preregistration of studies, while the OSF in general is a project management tool for researchers with various functions, for example storing and publishing data. The key characteristics of these registers are reported in Table 1. Data have been verified for all registers except OSF Registries (no response received). At the end of the article, in addition to the five registries, other options are described for how and where to prospectively and transparently determine one’s planned methods.

PROSPERO seems to be the most prominent option by far, as indicated by their high number of registrations. However, this popularity also seems to have led to increased turn-around times. While there is no information on the overall processing time in PROSPERO, there is some evidence that it may take up to several months [14]. It can be assumed that in particular the assessment of submissions for eligibility and completeness take time. Such checks are also performed in Research Registry and INPLASY. However, registration records become immediately visible in Research Registry as submissions are assessed after registration, while INPLASY promises a fast turn-around time taking no longer than 48 hours. Although fast turn-around times are highly appreciated by authors [15, 16], they come at the price of a having to pay a fee for the services offered by Research Registry and INPLASY. This might be problematic for systematic reviews without specific funding. Submissions to OSF Registries or protocols.io are not formally assessed, but these registers are also free of charge. Another advantage of both is that they offer services to share the data collected as part of the systematic review.

The three registers specific to systematic reviews have a given structure consisting of 24–28 mandatory fields. In OSF Registries, users can select from different registration forms or chose “Open-Ended-Registration” and provide a narrative summary of their systematic review registration. All registers can be searched for systematic reviews already registered in the register. PROSPERO offers most search tools, including use of Medical Subject Headings. However, it has previously been reported that PROSPERO’s search function is suboptimal [17]. It is unclear how well the search functions of the remaining registers exactly work, but one could argue that more sophisticated search functions must be implemented to facilitate efficient searches as the number of registrations increases. In a perfect world, the search functions should be similar as in bibliographic databases. Authors’ contact details are provided in the three systematic-review-specific registers, but not in OSF Registries and protocols.io. PROSPERO, OSF Registries and protocols.io enable version tracking, and INPLASY, OSF Registries and protocols.io provide Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) for registrations. Authors should note that there are differences between the registries with respect to their eligibility criteria. For example, PROSPERO only accepts reviews including at least one direct health-related outcome. Further information on the identified registers can be found in Table 2.

Additional options to prospectively and transparently determine one’s planned methods

In addition to publishing a protocol and registering a systematic review in one of the five registers described above, we identified further options for prospectively reporting one’s planned methods. However, we do not consider them as registers (see definition above).

First, there are online open access data repositories allowing users to upload time-stamped, version-tracked files with a DOI. These services can be used to upload protocol documents, but also any other type of data associated with a research project. Examples include the OSF (open source; https://osf.io/), Figshare (commercial; https://figshare.com/), or Zenodo (open source;funded by CERN, OpenAIRE and the European Union; https://zenodo.org/). Using OSF and Zenodo is suggested as an option in the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 explanation and elaboration (Box 6) [29]. Recently, the PreregRS template for preregistering research syntheses was published, which aims to guide researchers in preparing a file that can be uploaded to such repositories [30]. More data repositories can be found by searching re3data.org, a registry of research data repositories. One option specifically for systematic reviews is the Systematic Review Data Repository by the AHRQ [31]. Second, we identified a pre-registration service called AsPredicted by the Penn Wharton Credibility Lab [32]. AsPredicted allows users to create a time-stamped PDF with the planned methods that can be shared selectively via a unique URL, but which remains private until an author makes it public. Third, we identified the Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies (CAMARADES) by the Preclinical Systematic Review & Meta-analysis Facility (SyRF) [33]. SyRF shared protocols of systematic reviews of animal studies in in a standardized way on the CAMARADES website until 2018. Afterwards, the service was stopped, as systematic reviews of animal studies relevant to human health can nowadays be registered in PROSPERO. However, SyRF will continue to host systematic review protocols submitted previously [34]. Last, we also identified registration records for systematic reviews in ClinicalTrials.gov [35, 36]. While ClinicalTrials.gov aligns with our definition of a register, we did not consider it in our overview as it clearly has a different purpose, i.e., the prospective registration of clinical trials.

Discussion

The five identified registers have different characteristics and features which authors may want to consider when choosing a suitable register for their next systematic review. It seems that, among the systematic-review-specific registries, authors have to trade-off between the costs of registration and the processing time. While being the costliest, Research Registry is also the fastest register as records are published immediately. PROSPERO is used widely and is free of charge, but as PROSPERO receives funding from the United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), registrations from the UK are prioritized. While this is understandable, it may be problematic for users from outside the UK. Furthermore, there is a potential risk that funding will be discontinued at some point as it has previously been the case with the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects that were also hosted by the CRD and funded through the UK NIHR [37]. Thus, it seems to be necessary to discuss alternative financing schemes for registries, which are both fair and sustainable. However, this is also so case for clinical trials registers. Originally, it has been discussed to include a systematic review registry in clinical trials registries to use existing technology and resources efficiently and promote collaboration among trialists and reviewers [7].

Limitations

We identified several options to prospectively register a systematic review. While there are also important points regarding systematic review registers from a meta-perspective, this commentary is written from an author perspective. Furthermore, it is possible that we missed other available options and thus encourage others to share further options for the prospective registration of systematic reviews with us.

Conclusion

We identified five registries where authors can prospectively register their systematic review, three of which are systematic-review-specific and two generic ones. These registries come with different characteristics and features, for example in terms of the costs of registration, turn-around times, and funding/business model. For registers that are not operated for-profit, e.g., PROSPERO, the research community should discuss fair and sustainable financing models to ensure long-term access and performance.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- BEME:

-

Best Evidence Medical Education

- CAMRADES:

-

Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies

- CRD:

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- DOI:

-

Digital Object Identifier

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- KTDRR:

-

Center on Knowledge Translation for Disability and Rehabilitation Research

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health Research

- OSF:

-

Open Science Framework

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SyRF:

-

Systematic Review Facility

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

U.S. Congress. PUBLIC LAW 105–115—NOV. 21, Food and Drug Administration Moderization Act of 1997. 1997. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ115/pdf/PLAW-105publ115.pdf#page=16. Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

European Commission. Regulation (EU) no 536/2014 of the European parliament and of the council. OJEU. 2014;L 158:1–76.

The PLoS Medicine Editors. Best practice in systematic reviews: the importance of protocols and registration. PLOS Med. 2011;8(2):e1001009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001009.

Stewart L, Moher D, Shekelle P. Why prospective registration of systematic reviews makes sense. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-7.

Davies S. The importance of PROSPERO to the National Institute for Health Research. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-5.

Straus S, Moher D. Registering systematic reviews. CMAJ. 2010;182(1):13–4. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081849.

Booth A, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, Stewart L. Establishing a minimum dataset for prospective registration of systematic reviews: an international consultation. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27319. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027319.

Rombey T, Doni K, Hoffmann F, Pieper D, Allers K. More systematic reviews were registered in PROSPERO each year, but few records’ status was up-to-date. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;117:60–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.09.026.

Riaz IB, Khan MS, Riaz H, Goldberg RJ. Disorganized systematic reviews and meta-analyses: time to systematize the conduct and publication of these study overviews? Am J Med. 2016;129(3):339.e11–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.009.

Ioannidis JP. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12210.

Center on Knowledge Translation for Disability & Rehabilitation Research. About KTDRR’s Registry of Systematic Reviews. 2021. Available from: https://ktdrr.org/systematicregistry/about.html. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd. KSR Evidence. 2021. Available from: https://www.systematic-reviews.com/ksr-evidence/. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

Puljak L. Delays in publishing systematic review registrations in PROSPERO are hindering transparency and may lead to research waste. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111474.

Rombey T, Puljak L, Allers K, Ruano J, Pieper D. Inconsistent views among systematic review authors toward publishing protocols as peer-reviewed articles: an international survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.010.

Tawfik GM, Giang HTN, Ghozy S, Altibi AM, Kandil H, Le HH, et al. Protocol registration issues of systematic review and meta-analysis studies: a survey of global researchers. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01094-9.

Solla F, Bertoncelli CM, Rampal V. Does the PROSPERO registration prevent double review on the same topic? BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020;140. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111361.

Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-2.

Booth A, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, Stewart L. An international registry of systematic-review protocols. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):108–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60903-8.

Agha R, Rosin D. The Research Registry – answering the call to register every research study involving human participants. Int J Surg. 2015;16(Pt A):113–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.03.001.

Agha R, Rosin D. The Research Registry - answering the call to register every research study involving human participants. Ann Med Surg. 2015;4(2):95–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2015.03.001.

Nosek BA, Ebersole CR, DeHaven AC, Mellor DT. The preregistration revolution. PNAS. 2018;115(11):2600–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114.

Teytelman L, Stoliartchouk A, Kindler L, Hurwitz BL. Protocols.io: virtual communities for protocol development and discussion. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(8):e1002538. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002538.

Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. PROSPERO at one year: an evaluation of its utility. Syst Rev. 2013;2:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-2-4.

Page MJ, Shamseer L, Tricco AC. Registration of systematic reviews in PROSPERO: 30,000 records and counting. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0699-4.

Agha R, Fowler AJ, Limb C, Al Omran Y, Sagoo H, Koshy K, et al. The first 500 registrations to the Research Registry(®): advancing registration of under-registered study types. Front Surg. 2016;3:50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2016.00050.

Fowler AJ, Dowlut N, Limb R, Baldacchino MV, Sonagara V, George N, et al. Analysis of the first 2645 registrations at the research registry(®): a global repository for all study types involving human participants. Int J Surg. 2018;60:231–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.036.

Bakker M, Veldkamp CLS, van Assen M, Crompvoets EAV, Ong HH, Nosek BA, et al. Ensuring the quality and specificity of preregistrations. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(12):e3000937. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000937.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160.

Schneider J, Backfisch I, Lachner A. Facilitating Open Science Practices for Research Syntheses: PreregRS Guides Preregistration. Res Syn Meth. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1540.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Systematic review data repository. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. Available from: https://srdr.ahrq.gov/home/index. Accessed 5 May 2021

Penn Wharton Credibility Lab. AsPredicted. Philadelphia: University of Pennsilvania; 2021. Available from: https://aspredicted.org/. Accessed 5 May 20201

CAMARADES. Welcome to the CAMARADES Preclinical Systematic Review & Meta-analysis Facility (SyRF). 2021. Available from: http://syrf.org.uk/. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

SYRF Info. Personal communication via email on 18 January 2021. 2021.

Teichgräber U. Systematic review and meta-analysis on DCB vs. POBA in de-novo femoropopliteal disease (DOND). 2020. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02927574?term=systematic+review&draw=2&rank=10. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

GlaxoSmithKline. A systematic review of studies of the effect of influenza vaccine against mismatched strains. 2012. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01416597?term=systematic+review&draw=2&rank=8. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

Briscoe S, Cooper C, Glanville J, Lefebvre C. The loss of the NHS EED and DARE databases and the effect on evidence synthesis and evaluation. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(3):256–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1235.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Connor Evans from PROSPERO, Riaz Agha from Research Registry, João Vitor Canellas from INPLASY, and Emma Ganley from protocols.io for verifying the data related to their registry.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. There was no funding for the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DP and TR were equally involved in the conception and design of the work and the acquisition and interpretation of data. DP has drafted the work and TR has substantively revised it. Both authors approved the submitted version and agree to be personally accountable for the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DP and TR declare to have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pieper, D., Rombey, T. Where to prospectively register a systematic review. Syst Rev 11, 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01877-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01877-1