Abstract

Background

With the burden of prostate cancer, it has become imperative to exploit cost-effective ways to tackle this menace. Women have demonstrated their ability to recognize early cancer signs, and it is, therefore, relevant to include women in strategies to improve the early detection of prostate cancer. This systematic review seeks to gather evidence from studies that investigated women’s knowledge about (1) the signs and symptoms, (2) causes and risk factors, and (3) the screening modalities of prostate cancer. Findings from the review will better position women in the fight against the late detection of prostate cancer.

Methods

The convergent segregated approach to the conduct of mixed-methods systematic reviews was employed. Five databases, namely, MEDLINE (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Web of Science, and EMBASE (Ovid), were searched from January 1999 to December 2019 for studies conducted with a focus on the knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms, the causes and risk factors, and the screening modalities of prostate cancer.

Results

Of 2201 titles and abstracts screened, 22 full-text papers were retrieved and reviewed, and 7 were included: 3 quantitative, 1 qualitative, and 3 mixed-methods studies. Both quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that women have moderate knowledge of the signs and symptoms and the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer. However, women recorded poor knowledge about prostate cancer screening modalities or tools.

Conclusions

Moderate knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms and the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer was associated with education. These findings provide vital information for the prevention and control of prostate cancer and encourage policy-makers to incorporate health promotion and awareness campaigns in health policies to improve knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer globally.

Systematic review registration

Open Science Framework (OSF) registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-skin cancer occurring in men and is accountable for 3.8% of all mortality caused by cancer in men [1, 2]. According to the GLOBOCAN, 2018 database, it is estimated that it is the fifth primary cause of cancer death in men globally. It further reported that the highest mortality rate is found in the Caribbean and Southern African men worldwide [1, 3]. A recent study by Yeboah-Asiamah et al. reported that PCa was the second most common cancer in areas such as Australia, the USA, and New Zealand [4]. Though fewer than 30% of all incidence of PCa are from developing countries, these countries have previously been estimated to have the highest mortality from PCa due to late diagnosis [5, 6]. Although sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has a low rate of the disease, the incidence is projected to increase if screening is encouraged [7]. Hence, PCa remains a vital public health concern in both developed and developing countries.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in North America organized a workshop with the motive to explore strategies to control and prevent the disease based on the increasing incidence and mortality rate of PCa [8]. To address mortality rates related to the disease, participants recommended strategies to improve PCa awareness [8]. Also, as documented by many studies, PCa incidence is a direct reflection of the rate at which high-risk groups screen for the disease [4, 9]. In Europe, early screening was attributed to a 20% reduction in PCa mortality rate [10]. Although there is evidence suggesting a reduction in PCa mortality due to early screening, a United States (US) study did not highlight a reduction in mortality [11]. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the digital rectal examination (DRE) are useful screening tools, although initial controversies were surrounding the use of these tools [12]. Because of overlap in PSA levels in men with prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and PCa, it was assumed that PCa cannot be screened using the PSA test [13]. Catalona et al. demonstrated that PSA could be utilized as a screening tool for PCa, and it has widely been adopted [14]. DRE is the only procedure whereby physicians can examine part of the prostate gland [15]. The findings are only based on the physician impression, hence poor inter-rater reliability and also a limitation to the palpable region of the prostate gland [15]. However, DRE sometimes detects PCa in men with PSA, 4.0 ng/mL [16]. Regardless of the controversial nature of screening and the potential for early screening to reduce mortality, studies support the need to encourage screening [4, 12].

Women have essential characteristics that make them better managers of family health as compared to men. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is evidence positioning women as individuals who make adequate observations about the health of their partners [9, 17]. In promoting the early detection of PCa, women have been documented to observe the slightest symptoms presented by their partners and push them to seek medical attention [9, 18]. In a study conducted by Blanchard et al., it was recommended that efforts must be made to actively involve women in improving the timely detection of PCa through the closure of knowledge gaps [19].

Also, men admit seeking out their wives’ opinions as sources of health information [20]. In the context of the early detection of PCa, women can play various roles such as information seekers, advocates, health advisors, and support persons [21]. Therefore, there is the need to gather current evidence about women’s knowledge of PCa as the findings will be vital in equipping women to contribute towards the early detection of the disease.

In light of the availability of limited evidence addressing the awareness of women on prostate cancer, this review will seek to combine quantitative and qualitative data to increase the validity of findings through data triangulation as recommended by Caruth and supported by Lizarondo et al. [22, 23]. Thus, this review seeks to map out current evidence regarding women’s awareness of PCa under the scopes of (1) signs and symptoms, (2) risk factors and causes, and (3) screening guidelines.

Review question

Do women have adequate knowledge about prostate cancer?

Methodology

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) reviewer’s manual for the conduct of mixed-methods critical appraisal and synthesis formed the backbone of the study [23]. With guidance from the JBI manual, a protocol was developed to guide the review process according to the convergent segregated approach [23]. The respective DOIs of the review protocol and review, registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF), are https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EYHF2 and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456. The review protocol is readily available to the scientific community [24].

Inclusion criteria

The following were grounds for the inclusion of studies:

-

Studies that were conducted among women aged 18 years and above.

-

Studies that were conducted among women of all racial backgrounds.

-

Studies published from January 1999 to December 2019.

-

Studies that were conducted among women of all geographical locations.

-

Studies of all research designs.

-

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

-

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

-

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the screening recommendations of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

-

Studies that were published in the English language.

-

Studies with abstract and full text available.

Exclusion criteria

The following were grounds for the exclusion of studies:

-

Studies that were published before January 1999 or after December 2019.

-

Studies that were not published in the English language.

-

Studies that include women below the age of 18 years.

-

Studies in which the age of included women cannot be established.

-

Studies that did not indicate the number/percentage of included women.

-

Studies that exclusively included men without any women component (18 years and above).

-

Studies conducted among women who were previously given education on prostate cancer.

-

Studies that exclusively involved lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual/transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) participants.

-

Studies that exclusively included healthcare professionals.

-

Studies that exclusively involved healthcare and college/university students.

-

Studies that do not include the outcome of interest.

-

Book chapters.

-

Reviews and overviews.

-

Abstracts and conference papers.

-

Dissertations and thesis.

-

Commentaries and letters to editors.

-

Studies published without abstracts.

Information sources and search strategy

An initial explorative search in PubMed founded search terms in preparation for comprehensive electronic search. The selected search terms, applied as MeSH terms, were combined with Boolean operators for a comprehensive electronic search in MEDLINE (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Web of Science, and EMBASE (Ovid) as “(prostate cancer ) AND (awareness OR knowledge) AND (signs OR symptoms) AND (risk factors OR causes) AND (screening) AND (women)”. The search strategy (Additional file 1), so developed, was utilized by the first (EW) and second (KBM) reviewers to independently conduct a literature search as outlined in the review protocol e24].

Selection of studies

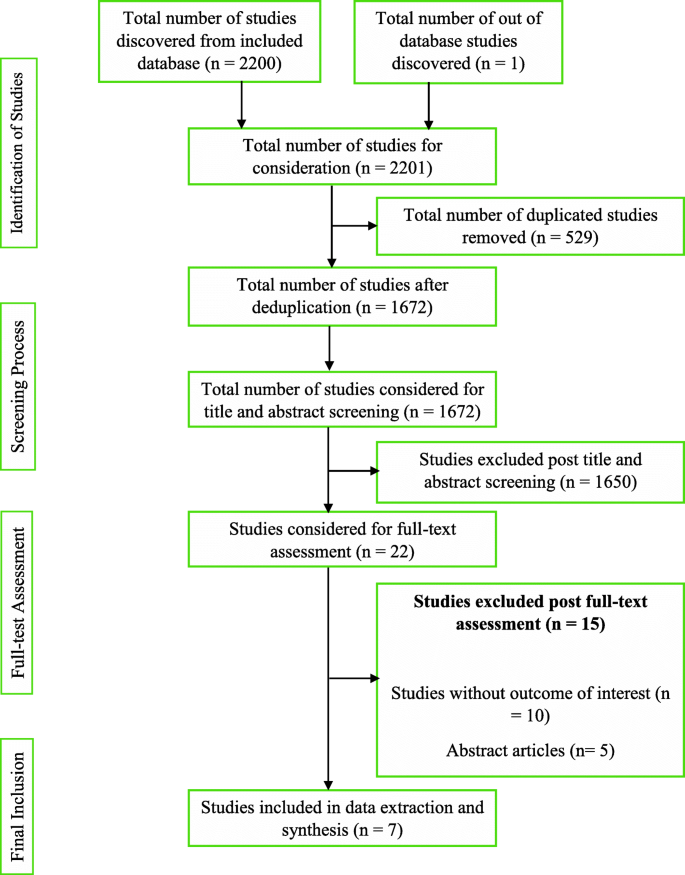

The first and second reviewers, being guided by the developed review protocol, singularly screened and compared the titles and abstracts of the literature search outcomes to a developed standard (the inclusion and exclusion criteria). Studies that successfully passed the initial stage of screening were subjected to the independent full-text reading by EW and KBM before consideration for data extraction. Lastly, hand-searching and snowballing on references of selected articles were done to find eligible studies in the grey area. There were no disagreements between EW and KBM. Hence, the third reviewer (ABBM) assessed the studies before data extraction was conducted by the lead author according to the JBI data extraction tools outlined in the review protocol [24]. The characteristic of studies that successfully went through the data extraction, the key findings that were extracted, and a summary of the study selection process are detailed respectively (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

As described in the review protocol [24], the methodological quality assessment tool (Additional file 2) was adopted and modified for this review due to the similarities this review shares with the study conducted by Mensah et al. [30]. The tool appraised the studies’ quality based on the study sample representativeness, response rate, reliability, and validity of the data collection tool. The tool was modified to suit the results from the included studies. A score was calculated, and the quality of the studies was classified as weak (0 to 33.9%), moderate (34 to 66.9%), or strong (67 to 100%). Eligible records were subjected to independent quality assessment by EW and KBM. Methodological quality outcomes were not grounds for exclusion.

Synthesis and integration of findings

The review findings were subjected to the convergent segregated approach to synthesis and integration according to the developed review protocol [24]. A narrative synthesis was separately performed for qualitative and quantitative findings. The heterogeneous nature of the review findings did not support the conduct of a meta-analysis. The results were finally integrated.

Results

Conducting the review, according to the developed protocol, yielded 2200 study results. A detailed citation screening led to an additional study, which increased the total number of studies to 2201. Regarding the summary of the study selection process (Fig. 1), 1672 studies were obtained after 529 duplicates were removed from the pool of data. Post-titles and abstract review excluded 1650 studies leaving 22 studies. The 22 studies were further reduced to 7 after a full-text reading resulted in the exclusion of 15 studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The data extracted from the seven (7) studies are detailed (Table 1). The publication years ranged from 2003 to 2018 with 5 studies having been conducted in the USA. One of the studies was a multicenter study that involved multinationals [28]. The study with the highest female participants (4040 women) was conducted in Spain [26]. Webb et al. recruited the lowest sample size, 14 women [29]. A total of 5634 women were involved in the 7 studies. Two studies were solely conducted in women, three included other diseases, and two did not disclose study duration.

Quality of included studies

According to the scoring scheme of the quality assessment tool (Additional file 2), two studies [26, 29] were evaluated as moderate quality whilst five studies were evaluated as strong quality. None of the studies was excluded based on methodological quality assessment outcomes. There was no disagreement between EW and KBM.

Review findings

Study findings, presented in Table 2, were heterogeneous. Quantitative studies indicate that women knew about the existence of PCa. In exploring qualitative evidence, women exhibited knowledge of PCa. Therefore, both arms of the review are supportive of each other.

Women had moderate knowledge about the signs and symptoms of PCa drawing from quantitative findings. Women knew about the asymptomatic nature of the early stages of PCa. They also moderately knew urinary symptoms such as urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, and dysuria. Qualitative studies indicate that women were aware prostate cancer patients, usually in advanced stages, could present with signs and symptoms such as urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, glandular enlargement of the prostate, and erectile dysfunction. Hence, quantitative and qualitative findings revealed that women moderately knew the urinary symptoms of PCa.

Quantitative studies indicate an average score of women on knowledge of risk factors of PCa. Risk factors women knew were increasing age, presence of a first-degree relative, being genetically linked to Africa, and excessive truncal obesity. Qualitative evidence recognized all risk factors documented by the quantitative findings except truncal obesity. Also, identified risk factors included poor diet, inadequate exercise, stressful lifestyle, poor screening habits, cigarette smoking, and poor access to quality healthcare. Women wrongly reported sexual orientation and frequent sexual activity as risk factors. Therefore, qualitative findings confirm the quantitative claim that women have shared knowledge about the risk factors of PCa.

Quantitative studies indicate that women had poor knowledge about PCa screening guidelines, appropriate screening samples, and tools. Although it was reported that women knew about PSA and DRE, the proportions of women who had correct responses to screening knowledge items were not appreciable. Women poorly recognized urine as a screening sample, PSA as an exclusive diagnostic tool (where only 17.5% answered correctly), and failed to identify more than one screening tool (between 41 and 71% of women failed). Qualitative studies respectively reported PSA and blood as a screening tool and sample. Colonoscopy was wrongly reported as a PCa screening tool. Conclusively, both arms of the review reported women knew about PSA and had poor knowledge about PCa screening.

Discussion

The heterogeneity of the study findings warranted the synthesis as a narrative [23, 31]. The convergent segregated approach was employed according to the recommendation of the JBI reviewer’s manual [23].

Generally, from the quantitative evidence, women knew about prostate cancer [19, 25, 27, 28]. The knowledge of women was found to have increased with educational and financial status [19], and disease familiarity [19, 25]. The awareness of women about the existence of PCa increased when the disease was mentioned compared to an initial request for women to list cancers [28]. Qualitative evidence showed that women were aware of PCa [18, 27]. They appreciated and specifically requested for PCa education partly because they could not tell the location of the prostate gland [18]. Thus, quantitative and qualitative evidence indicates that women know about PCa. Women’s awareness could be due to their role in family health management and the possible health-seeking behavior of educated and financially strong women. As persons are faced with the experiences of a health condition, they will seek to make sense of this illness by acquiring knowledge [32], experiences, and beliefs; hence, this theory might explain the improved awareness of women who were familiar with the disease.

Most of the quantitative studies indicate that women are aware of the asymptomatic nature of early-stage PCa [19, 25, 27]. Symptoms that women had a fair knowledge about included urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, and dysuria [25]. Findings from one of the qualitative studies indicate that women fairly recognized urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, glandular enlargement of the prostate, and erectile dysfunction as signs and symptoms of PCa [18]. Being familiar with the disease may explain the awareness of women of the urinary symptoms associated with PCa.

According to Okoro and colleagues’ quantitative study, although knowledge of PCa was not adequate, women knew associated risk factors such as being a first-degree relative, being a man of African descent, and excessive truncal obesity [27]. Blanchard et al. also documented women’s recognition of increasing age as a PCa risk factor [19]. One of the qualitative studies indicates women knew increasing age could increase a man’s chance for PCa development [18, 29]. Other causes and risk factors women identified included poor diet, inadequate exercise, stressful lifestyle, family history of the disease, being of African descent, poor screening habits, cigarette smoking, and poor access to quality healthcare [18]. Erroneously, one study reported that women perceived sexual orientation and frequent sexual activity as risk factors [18]. Both quantitative and qualitative findings documented women knew increasing age, family history, and African descent as PCa risk factors.

Quantitatively, women’s responses to queries about PCa screening were poor [25, 28]. Some women were unable to recognize at least a PCa screening tool whilst others mistakenly recognized urine as a suitable sample for PCa screening [28]. According to Okoro et al., the majority of women exclusively tagged PSA elevation as a basis for PCa diagnosis [27]. This, therefore, calls for extensive education because benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, and PCa usually present with elevated PSA [13]. Evidence from qualitative findings indicated women knew physical examination must augment blood analysis [29]. Also, women mentioned PSA and colonoscopy as screening tools [18]. The results from included qualitative studies confirmed that women had poor knowledge about PCa screening. The mention of colonoscopy as a screening tool further supports a lack of adequate knowledge about PCa screening.

This critical appraisal and synthesis revealed over the 20 years of study search, only four studies out of the seven included studies investigated all the outcomes of interest. Two studies did not investigate women’s awareness of the signs and symptoms [26, 29] and the causes and risk factors [25, 26] of PCa. Therefore, although quantitative and qualitative findings were supportive of each other, studies investigating the causes and risk factors, as well as the signs and symptoms of PCa, were lacking.

Recommendations for practice

From the review findings, it is recommended that PCa control programs should also focus on educating women. Clinicians and public health practitioners should include women in prostate cancer health promotion. Women should be encouraged to attend PCa clinics with their male significant others suffering from the disease, and the effect of this strategy in reducing PCa mortality rate must be investigated.

Recommendations for research

Further studies are recommended to investigate the knowledge of women living in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) about PCa. Such studies should focus extensively on the knowledge of women on PCa screening. Also, it is recommended for research to develop and pilot a PCa educational intervention model, applicable to women to reduce the burden of the disease. This tool should be culturally specific for easy acceptance and recognition. Also, current evidence on the willingness of women to offer social support to men with PCa should be investigated.

Study limitations

The various restrictions that were imposed on the literature search included a search range from January 1999 to December 2019, a search into only 5 databases, and the outright exclusion of non-English publications. These constitute selection bias. Therefore, some important studies could have been left out of the review.

Although five (5) out of the seven (7) included studies explicitly indicated recruiting participants of African backgrounds, none of the studies were conducted in Africa. Hence, the global generalizability of the review findings, to most importantly cover low and middle-income countries, cannot be documented.

The exclusion of studies conducted in women who received education on prostate cancer, healthcare professionals, healthcare students, and college/university students, and further exclusion of studies that involved (LGBTQ) participants further constitute selection bias.

It is imperative to note that the various limitations, in connection to the included studies, documented in Table 2 have an effect on this review and, as such, could be considered as potential limitations.

Availability of data and materials

Data and other pieces of information are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- DRE:

-

Digital rectal examination

- GLOBOCAN:

-

Global cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence

- JBI:

-

Joanna briggs institute

- LGBTQ:

-

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual/transgender, and queer/questioning

- OSF:

-

Open science framework

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- PCa:

-

Prostate cancer

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- US:

-

United States

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

James LJ, Wong G, Craig JC, Hanson CS, Ju A, Howard K, et al. Men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PloS One. 2017;12(11):e0188258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188258.

GLOBOCAN. GLOBOCAN 2008: Ghana Fact Sheets. 2018. Available from: file:///C:/Users/user-pc/Downloads/288-ghana-fact-sheets.pdf.

Yeboah-Asiamah B, Yirenya-Tawiah D, Baafi D, Ackumey M. Perceptions and knowledge about prostate cancer and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among male teachers in the Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. Afr J Urol. 2017;23(4):184-91.

Rebbeck TR, Devesa SS, Chang B-L, Bunker CH, Cheng I, Cooney K, et al. Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of African descent. Prostate Cancer. 2013;2013:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/560857.

Mofolo N, Betshu O, Kenna O, Koroma S, Lebeko T, Claassen FM, et al. Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a urology clinic, a South African study. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0824-y.

Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D, O'Brien M, Ferlay J, Center M, et al. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4372–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27410.

Dimah KP, Dimah A. Prostate cancer among African American men: a review of empirical literature. Journal of African American Studies. 2003;7(1):27–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-003-1001-x.

Rashid P, Denham J, Madjar I. Do women have a role in early detection of prostate cancer? Lessons from a qualitative study. Aust Fam Phys. 2007;36(5):375.

Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810084.

Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1310–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810696.

Nakandi H, Kirabo M, Semugabo C, Kittengo A, Kitayimbwa P, Kalungi S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Ugandan men regarding prostate cancer. Afr J Urol. 2013;19(4):165–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afju.2013.08.001.

Catalona WJ. Prostate cancer screening. Med Clin. 2018;102(2):199–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.11.001.

Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, Dodds KM, Coplen DE, Yuan JJ, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(17):1156–61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199104253241702.

Wilbur J. Prostate cancer screening: the continuing controversy. Am Fam Phys. 2008;78(12):1377–84.

Federman DG, Pitkin P, Carbone V, Concato J, Kravetz JD. Screening for prostate cancer: are digital rectal examinations being performed? Hosp Pract. 2014;42(2):103–7. https://doi.org/10.3810/hp.2014.04.1108.

Karim R, Lindberg L, Wamala S, Emmelin M. Men’s perceptions of women’s participation in development initiatives in rural Bangladesh. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(2):398–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988317735394.

Owens OL, Friedman DB, Hebert J. Commentary: Building an evidence base for promoting informed prostate cancer screening decisions: an overview of a cancer prevention and control program. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.27.1.55.

Blanchard K, Proverbs-Singh T, Katner A, Lifsey D, Pollard S, Rayford W. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of women about the importance of prostate cancer screening. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1378–85.

Taylor KL, Turner RO, Davis JL III, Johnson L, Schwartz MD, Kerner J, et al. Improving knowledge of the prostate cancer screening dilemma among African American men: an academic-community partnership in Washington, DC. Public Health Rep. 2016;116(6):590–8.

Miller SM, Roussi P, Scarpato J, Wen KY, Zhu F, Roy G. Randomized trial of print messaging: the role of the partner and monitoring style in promoting provider discussions about prostate cancer screening among African American men. Psychooncol. 2014;23(4):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3437.

Caruth GD. Demystifying mixed methods research design: a review of the literature. Mevlana Int J Educ. 2013;3(2):112–22. https://doi.org/10.13054/mije.13.35.3.2.

Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews.: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017 [Available from: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter+8%3A+Mixed+methods+systematic+reviews.

Wiafe E, Mensah KB, Mensah ABB, Bangalee V, Oosthuizen F. The awareness of women on prostate cancer: a mixed-methods systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):1–6.

Brown N, Naman P, Homel P, Fraser-White M, Clare R, Browne R. Assessment of preventive health knowledge and behaviors of African-American and Afro-Caribbean women in urban settings. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1644–51.

Carrasco-Garrido P, Hernandez-Barrera V, Lopez de Andres A, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Gallardo Pino C, Jimenez-Garcıa R. Awareness and uptake of colorectal, breast, cervical and prostate cancer screening tests in Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(2):264–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt089.

Okoro ON, Rutherford CA, Witherspoon SF. Leveraging the family influence of women in prostate cancer efforts targeting African American Men. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5(4):820–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0427-0.

Schulman CC, Kirby R, Fitzpatrick JM. Awareness of prostate cancer among the general public: findings of an independent international survey. European Urology. 2003;44(3):294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00200-8.

Webb CR, Kronheim L, Williams JE, Hartman TJ. An evaluation of the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of African-American men and their female significant others regarding prostate cancer screening. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):234–8.

Mensah KB, Oosthuizen F, Bonsu AB. Cancer awareness among community pharmacist: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4195-y.

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence: the Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017 [Available from: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter+2%3A+Systematic+reviews+of+qualitative+evidence.

Petrie K, Weinman J. Why illness perceptions matter. Clin Med. 2006;6(6):536–9. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.6-6-536.

Acknowledgements

The review team gives recognition to Dr. Richard Ofori-Asenso.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EW is credited with the conception of the review, the coordination of the systematic review, the development of the search strategy, the search and selection of studies to be included in the review, the extraction and management of quantitative and qualitative data, the assessment of methodological quality, the filtering of all reference materials, the integration and interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the manuscript, and is the principal reviewer. KBM is credited with the conception of the review, the review of the search strategy, the search and selection of studies to be included in the review, the extraction and management of quantitative and qualitative data, the assessment of methodological quality, the integration and interpretation of the data, and the review of the manuscript. ABBM is credited with the review of the search strategy, the assessment of the studies before data extraction, and the review of the manuscript. VB is credited with the review of the manuscript, the coordination of the systematic review, and the as co-supervisor of the review. FO is credited with the conception of the review, the review of the manuscript, and the overall supervision of the review. All authors have reviewed and accepted the final manuscript of the review for publication. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical permission was not required since the study did not involve the enrollment of humans or animals as study subjects.

Consent for publication

None.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

Proposed search strategy using Medline via EBSCOhost

Additional file 2:.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiafe, E., Mensah, K.B., Mensah, A.B.B. et al. Knowledge of prostate cancer presentation, etiology, and screening practices among women: a mixed-methods systematic review. Syst Rev 10, 138 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01695-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01695-5