Abstract

Background

A previous study found that 2 of 29 (6.9%) meta-analyses published in high-impact journals in 2009 reported included drug trials’ funding sources, and none reported trial authors’ financial conflicts of interest (FCOIs) or industry employment. It is not known if reporting has improved since 2009. Our objectives were to (1) investigate the extent to which pharmaceutical industry funding and author-industry FCOIs and employment from included drug trials are reported in meta-analyses published in high-impact journals and (2) compare current reporting with results from 2009.

Methods

We searched PubMed (January 2017–October 2018) for systematic reviews with meta-analyses including ≥ 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of patented drugs. We included 3 meta-analyses published January 2017–October 2018 from each of 4 high-impact general medicine journals, high-impact journals from 5 specialty areas, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, as in the previous study.

Results

Among 29 meta-analyses reviewed, 13 of 29 (44.8%) reported the funding source of included trials compared to 2 of 29 (6.9%) in 2009, a difference of 37.9% (95% confidence interval, 15.7 to 56.3%); this included 7 of 11 (63.6%) from general medicine journals, 3 of 15 (20.0%) from specialty medicine journals, and 3 of 3 (100%) Cochrane reviews. Only 2 of 29 meta-analyses (6.9%) reported trial author FCOIs, and none reported trial author-industry employment.

Protocol Publication

A protocol was uploaded to the Open Science Framework prior to initiating the study. https://osf.io/8xt5p/

Limitations

We examined only a relatively small number of meta-analyses from selected high-impact journals and compared results to a similarly small sample from an earlier time period.

Conclusions

Reporting of drug trial sponsorship and author FCOIs in meta-analyses published in high-impact journals has increased since 2009 but is still suboptimal. Standards on reporting of trial funding described in the forthcoming revised PRISMA statement should be adapted and enforced by journals to improve reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Financial conflicts of interest (FCOIs) in drug trials can influence trial design, drug dosages and comparators, data analysis, interpretation of findings, and the likelihood that favorable results are reported [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Industry-sponsored trials are approximately 30% more likely to report favorable efficacy results and conclusions than non-sponsored trials, and this is not explained by other trial elements associated with risk of bias [6]. Similarly, trials conducted by principal investigators with FCOIs have higher odds of reporting positive outcomes than trials led by non-affiliated principal investigators, controlling for trial funding source [7].

Meta-analyses are highly cited [8] and are prioritized in the development of clinical practice guidelines and in setting research priorities [9,10,11]. A review of a sample of 29 meta-analyses of drug trials published in high-impact medical journals in 2009, however, reported that only 2 (6.9%) reported funding sources and none reported author FCOIs or industry employment from included trials [12]. A 2012 review of 151 Cochrane reviews of drug trials found that only 46 (30.5%) reported the funding source of some or all included trials; only 16 (10.6%) provided any information on author FCOIs or industry employment [13].

In 2012, the Cochrane Collaboration began to require that funding sources and author FCOIs be reported for all trials included in Cochrane reviews [14,15,16]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement, which was published in 2009 [17, 18], however, did not address reporting of trial funding and author-industry financial ties from included trials. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines require that meta-analysis authors declare their own FCOIs but do not address reporting of study funding or author FCOIs of included trials [19].

The objectives of this study were to (1) investigate the extent to which pharmaceutical industry funding and author-industry financial ties and employment from drug trials synthesized in meta-analyses are reported in meta-analyses published in high-impact journals and (2) compare current reporting with results from 2009 [12].

Methods

Our study protocol was published on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/8xt5p/) and followed the methods of the previous Roseman et al. [12] study with 2 exceptions. First, whereas the previous study was limited to a 10-month period (January to October 2009), we extended the period to 22 months a priori (January 2017 to October 2018) to improve the likelihood that we could include the same number of meta-analyses from each journal or specialty area. Second, in addition to extracting reporting of trial information in meta-analyses, the previous study [12] reviewed FCOIs from all included trials. Since it is well-established that FCOIs are common in drug trials [1, 12, 20], we examined reporting in meta-analyses, but did not extract information from included trials.

Study selection

To be included, publications had to include at least 1 meta-analysis that (1) was part of a documented systematic review, (2) statistically combined results from ≥ 2 RCTs, (3) did not include non-RCTs, (4) evaluated the efficacy or harm of a drug or class of drugs, and (5) included at least 1 drug in any study arm under patent in the USA at the time of publication based on the electronic US Food and Drug Administration Orange Book [21]. Drugs were defined broadly to include biologics and vaccines but not nutritional supplements (e.g., vitamins) or medical devices without a drug component. Status of potential drug products not found in the FDA database, such as products registered as drugs only outside of the USA, was determined by review of team members and consensus. A drug was considered under patent if any aspect of the active ingredient (e.g., dosage, route, strength) was protected by an unexpired patent. We included the patent requirement to restrict the sample to drugs of potential economic importance to pharmaceutical companies. See Additional Methods 1 for the title/abstract and full-text eligibility coding guides.

Data sources and searches

We selected a sample of meta-analyses published from January 1, 2017, to October 25, 2018, in 3 categories of high-impact publications: (1) general medicine journals, (2) journals from 5 specialty medicine areas (oncology, cardiology, respiratory medicine, endocrinology, and gastroenterology), and (3) the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [12].

In the previous study [12], among general medicine journals, we selected the 3 most recently published eligible meta-analyses from each journal with a 2008 impact factor ≥ 10 (New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, Lancet, BMJ, Annals of Internal Medicine, PLoS Medicine) with fewer included if < 3 met eligibility criteria. Neither the New England Journal of Medicine nor PLoS Medicine had any eligible meta-analyses, and the Annals of Internal Medicine had only 2. Thus, in the present study, only meta-analyses from JAMA, Lancet, BMJ, and Annals of Internal Medicine were eligible, and we included only 2 meta-analyses from Annals of Internal Medicine.

In the previous study [12], we selected the top 5 specialty areas based on 2008 global pharmaceutical sales. For the present study, we included the same 5 specialty areas (oncology, cardiology, respiratory medicine, endocrinology, and gastroenterology). In each specialty area, we included the 3 most recently published eligible meta-analyses in the top impact factor journal in the specialty area based on the 2016 Clarivate Analytics Science Citation Index. If 3 eligible meta-analyses were not published in the top journal, we searched the journal with the next highest impact factor and continued in declining order of impact factor until 3 eligible meta-analyses were identified.

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed using limits of article type (“meta-analysis”) with journal names, supplemented by a manual search of each journal’s table of contents. Articles published online ahead of print, but not in the final format, as of the search date were not eligible. For articles published in the same journal issue, the one with the highest page number was considered most recent. In each Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews issue, meta-analyses were reviewed in reverse sequence as the most recently published reviews are listed first.

Data extraction

We uploaded search results into the systematic review software DistillerSR® for inclusion and exclusion and result coding. Review of identified articles from each general medicine journal, specialty medicine area, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was conducted independently by 2 reviewers, 1 article at a time, in reverse temporal sequence until the targeted number of eligible meta-analyses was obtained. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus, involving a third reviewer if necessary.

Two investigators independently reviewed all included meta-analyses, including disclosure statements, article texts and tables, author bylines and acknowledgments, and online journal supplements to identify (1) in the meta-analysis: disclosed funding sources, author-industry financial ties, author-industry employment, and whether a quality or risk of bias assessment was conducted, and (2) whether or not the meta-analysis reported trial funding, author-industry financial ties, and author-industry employment from included drug RCTs. See Additional Methods 2 for the Meta-Analysis Data Extraction dictionary. Additionally, in February 2020, we examined author instructions from all journals with included meta-analyses to determine if they included instructions on reporting of funding sources, author-industry financial ties, or author-industry employment for studies included in meta-analyses published in the journal.

Data synthesis and analysis

Study funding sources for meta-analyses were classified as pharmaceutical industry, non-industry (e.g., public granting agency, private not-for-profit granting agency), combined pharmaceutical industry and non-industry, no study funding, or not reported. Meta-analyses reported as funded “in part” by the pharmaceutical industry with no other indication of funding source or funded by a not-for-profit organization fully sponsored by pharmaceutical industry sources were coded as industry-funded. Industry funding was considered to be a provision of financial support, resources (e.g., statistical analyses), or study personnel.

Meta-analysis author financial ties to industry were defined per the ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest [19] and included current or former board membership, current or former consultancy, former industry employment, equity holdings (e.g., stock ownership, stock options), expert testimony, gifts, patents (planned, pending, issued), payment for manuscript preparation, other research funding, royalties, speaker fees/payment for presentation development, travel reimbursement, or other unspecified FCOIs, as disclosed in the article. If an article did not contain a disclosure statement, author-industry financial ties were coded as not reported. Authorship by persons employed by the pharmaceutical industry at the time of article publication was coded separately as “industry employment.”

For reporting in meta-analyses of trial funding, author-industry financial ties, and author-industry employment from included drug RCTs, for each category, we determined if the meta-analysis reported for all, some, or no included RCTs. When information was reported, we determined where information could be found in the meta-analysis (e.g., text, characteristics of studies table, risk of bias assessment, footnote).

Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus, including consultation with a third reviewer if necessary.

We reported descriptive characteristics of included meta-analyses, their funding, and author-industry financial ties. To compare the proportion of meta-analyses that reported study funding, author financial ties, and author employment from included RCTs, we generated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the differences in proportions [22].

Role of the funding source

No funder had any role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Dr. Thombs had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Article selection

A total of 176 publications were reviewed (37 from general medicine journals, 121 from specialty medicine journals, 18 from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) to obtain the 29 that were included in the review (Fig. 1) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. As shown in Table 1, impact factors of journals with included publications ranged from 17.2 to 47.8 in general medicine, 11.9 to 24.0 in oncology, 19.3 to 19.9 in cardiology, 10.3 to 10.6 in respiratory medicine, 11.9 to 19.7 in endocrinology, 16.7 to 18.4 in gastroenterology, and 6.3 for the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The 29 selected meta-analyses evaluated a broad spectrum of pharmacological interventions, including 11 on treatment efficacy [24, 29, 33, 35, 36, 40, 42, 44,45,46,47], 2 on harms [31, 50], and 16 [23, 25, 28, 30, 32, 34, 37,38,39, 41, 43, 48, 49, 51] on both efficacy and harms. Between 2 and 522 RCTs were included in each meta-analysis. None of the journals with included meta-analyses mentioned reporting of funding or author FCOI of studies included in meta-analyses that are published in the journal.

Study funding and author-industry financial ties of meta-analyses

As shown in Tables 1 and 2 of 29 (6.9%) included meta-analyses, both published in specialty journals [34, 43], reported receiving pharmaceutical industry funding, 11 (37.9%) reported non-industry funding [23, 26, 29,30,31,32, 35, 40, 49,50,51], 3 reported no study funding (10.3%) [28, 33, 46], and the funding source of 13 (44.8%) was not reported [24, 25, 27, 36,37,38,39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 48]. Meta-analysis funding sources were reported for 8 of 11 meta-analyses from general medicine journals (72.7%) [23, 26, 28,29,30,31,32,33], 5 of 15 (33.3%) from specialty medicine journals [34, 35, 40, 43, 46], and all 3 (100%) Cochrane reviews [49,50,51].

All 29 meta-analyses included author COI statements. In 15 of the 29 meta-analyses (51.7%), at least 1 author reported 1 or more financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry [24,25,26, 29, 34, 35, 37,38,39,40, 43, 45, 47, 49, 50], whereas all authors reported no financial ties in 14 (48.3%) [23, 27, 28, 30,31,32,33, 36, 41, 42, 44, 46, 48, 51]. In 5 of 29 (17.2%) meta-analyses [34, 35, 38, 39, 43], all published in specialty medicine journals and including the 2 meta-analyses with industry funding [34, 43], the majority of authors had financial ties to industry. Author-industry financial ties were present in 4 of 11 meta-analyses published in general medicine journals (36.4%) [24,25,26, 29], 9 of 15 (60.0%) in specialty medicine journals [34, 35, 37,38,39,40, 43, 45, 47], and 2 of 3 (66.7%) Cochrane reviews [49, 50]. Specific types of author ties to industry are shown in Table 2.

Reporting of trial funders and author FCOI from RCTs included in meta-analyses

As shown in Table 3, 13 of 29 (44.8%) meta-analyses reported the funding sources of included RCTs; 12 reported for all included RCTs [23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 45, 49,50,51], whereas 1 reported for 5 of 7 included RCTs [39]. Funding sources of included RCTs were reported for 7 of 11 (63.6%) meta-analyses from general medicine journals [23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32], 3 of 15 (20.0%) from specialty medicine journals [34, 39, 45], and for all 3 (100%) Cochrane reviews [49,50,51]. The mean, median, and range of the number of RCTs in meta-analyses that reported trial funding sources were 52.9, 13, and from 2 to 522, respectively. For those that did not report funding sources, they were 29.2, 16, and from 3 to 236, respectively.

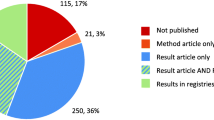

Only 2 of the 29 meta-analyses (6.9%) reported trial author-industry financial ties, including 1 from a general medicine journal [24] and 1 Cochrane review [49]. None of the 29 meta-analyses reported industry employment status of included RCT authors. See Fig. 2.

Comparison of reporting of industry funding of included RCTs in 2017–2018 versus 2009

The overall percentage of meta-analyses of drug treatments that reported the funding source of included RCTs increased from 6.9% (2 of 29) in 2009 to 44.8% (13 of 29) in 2017–2018, a difference of 37.9% (95% CI, 15.7 to 56.3%). This included an increase from 0% (0 of 11) to 63.6% (7 of 11) in general medicine journals (difference 63.6%; 95% CI, 25.3 to 84.8%), an increase from 6.7% (1 of 15) to 20.0% (3 of 15) in specialty medicine journals (difference 13.3%; 95% CI, − 13.2 to 39.1%), and an increase from 1 of 3 (33.3%) to 3 of 3 (100%) among Cochrane reviews.

Discussion

The main finding was that the reporting of funding sources of drug trials included in meta-analyses in high-impact journals improved, from 2 of 29 (6.9%) in 2009 to 13 of 29 (44.8%) in 2017–2018, but it continues to be sub-optimal. Only 2 of 29 (6.9%) meta-analyses provided information on author-industry financial ties from included trials, and no meta-analyses reported if industry employees were involved in the trials.

In 2012, the Cochrane Collaboration began to require that trial funding sources and conflicts of interest of authors of included trials be reported in the “characteristics of included studies” table of all Cochrane reviews [15], and this is still mandatory [16]. We evaluated 3 Cochrane reviews, and all 3 reported trial funding sources, but only 1 of 3 provided information on author-industry financial ties from included trials. A recent study [52] that investigated the extent to which recently published meta-analyses reported trial funding, author-industry financial ties, and author-industry employment from included RCTs found that reporting of trial funding in Cochrane meta-analyses increased from 30% (46 of 151 reviews) in 2010 to 84% (90 of 107) in 2016–2018. Reporting of trial author-industry financial ties increased from 7% (11 of 151) in 2010 to 44% (47 of 107) in 2016–2018, which suggests that this could still improve. Non-Cochrane meta-analyses published in 2016–2018 reported funding sources of included studies 15% of the time (21 of 143) and author-industry financial ties from included trials 1% of the time (2 of 143).

Cochrane reviews are recognized for their rigor [53] and often seen as the standard for systematic reviews on the benefits and harms of health care interventions [54, 55]. Consistent with this, Cochrane reporting standards are highlighted on the PRISMA website [56]. Ideally, the Cochrane Collaboration would ensure that authors of reviews adhere to both the requirement to report funding of trials included in reviews and to report author-industry financial ties from those trials. Nonetheless, Cochrane provides an example of how institutional commitment can lead to change on a large scale, which suggests that other journals could achieve similar results, but that it would require explicit guidance from journal editors and enforcement of that guidance.

The original PRISMA statement, which was published in 2009, did not address reporting of the funding sources of studies included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses or the FCOIs of study authors [17, 18]. An updated PRISMA statement is forthcoming and, though not completed, based on a preliminary version will likely encourage, though not required, reporting of funding and author FCOI from studies included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (personal communication, David Moher, February 13, 2020). It is possible that including encouragement to report on funding and FCOI in PRISMA could improve reporting, but the lack of a strong requirement and inclusion as an item in the checklist itself and the general low adherence to PRISMA [57] suggests that this may not have a strong effect.

It is not clear why general medicine journals improved in reporting between 2009 and the present study. It is unlikely related to PRISMA, since the existing PRISMA statement does not touch upon this issue. It is possible that this may be due to a more general awareness of these issues, that Cochrane added this requirement for its reviews, or a higher scrutiny by editors of these journals than previously or compared to specialty journals. None of the general medicine or specialty journals included in our review mention the reporting of funding sources or author FCOI from studies included in systematic reviews in their instructions to authors. Ideally, the forthcoming PRISMA checklist would include funding and FCOI of studies included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses as a dedicated item, which could support improvements in reporting, if adopted and enforced by reviewers and editors.

We previously recommended that the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [58] be revised to include risk of bias due to industry sponsorship of trials and FCOIs of trial investigators [12]. This would be consistent with empirical evidence that has linked both sponsorship and other FCOIs to trial outcomes, controlling for other factors known to be associated with bias [6, 7, 14]. There is no, however, consensus on this approach [14, 59]. Currently, an alternative is being created to explicitly address risk of bias from industry sponsorship of trials and author-industry financial ties in Cochrane reviews, the Tool for Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Trials (TACIT) [60]. Once completed, TACIT will include a Conflicts of Interest Grid, which will facilitate a systematic collection of relevant information and allow for determination of when there is notable concern, which may then be integrated into an assessment of risk of bias. In the present study, only 3 meta-analyses, 1 of which was a Cochrane review, attempted to incorporate funding sources of included trials into an assessment of risk of bias.

In interpreting results from this study, there are limitations to consider. First, the focus of the study was on reporting of trial funding and trial author FCOIs, and it was not designed to assess whether these were associated with meta-analysis quality or with the results of meta-analyses. Second, in replicating the methods of the previous study from 2009 [12], we selected 29 meta-analyses from high-impact journals in general medicine and 5 specialty areas for review; thus, it is not known to what degree these results may be generalizable to other areas of medicine or to lower impact journals. Third, we examined only a relatively small number of meta-analyses and compared results to a similarly small sample from an earlier time period.

Conclusion

In summary, reporting of funding sources of included trials in meta-analyses of drug treatments published in high-impact journals has improved since 2009 but is still alarmingly low. Fewer than half of the meta-analyses we reviewed reported funding sources of included trials, and fewer than a third provided information on trial funding in the main meta-analysis report. Reporting of trial author FCOIs and industry employment is even more concerning. Only 2 studies reported trial author-industry financial ties, and none directly reported whether industry employees were authors of included trials. Confidence in medical research and the quality of care delivered by those who rely on evidence from meta-analyses depends on transparent reporting and the ability to evaluate the degree to which conflicts of interest may have influenced trial design, conduct, and outcomes. The forthcoming revised PRISMA statement will require transparent reporting of funding in trials included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and the new TACIT tool is being developed by the Cochrane Collaboration to supplement its risk of bias tool and to integrate considerations of FCOIs into bias assessment. We encourage uptake of both of these tools by journals and authors of systematic reviews and meta-analyses so that the potential influence of industry sponsorship and other author-industry ties can be considered by users of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Abbreviations

- FCOI:

-

Financial conflicts of interest

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Sismondo S. How pharmaceutical industry funding affects trial outcomes: causal structures and responses. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(9):1909–14.

Bero LA, Rennie D. Influences on the quality of published drug studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12(2):209–37.

Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):252–60.

Rising K, Bacchetti P, Bero L. Reporting bias in drug trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration: review of publication and presentation. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e217.

Melander H, Ahlqvist-Rastad J, Meijer G, Beermann B. Evidence b(i)ased medicine—selective reporting from studies sponsored by pharmaceutical industry: review of studies in new drug applications. BMJ. 2003;326(7400):1171–3.

Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017;2:MR000033.

Ahn R, Woodbridge A, Abraham A, et al. Financial ties of principal investigators and randomized controlled trial outcomes: cross-sectional study. BMJ. 2017;356:i6770.

Patsopoulos NA, Analatos AA, Ioannidis JP. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2362–6.

Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ. 2001;323(7308):334–6.

Institue of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–65.

Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA, Coyne JC, Lexchin J, Turner EH, et al. Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. JAMA. 2011;305(10):1008–17.

Roseman M, Turner EH, Lexchin J, Coyne JC, Bero LA, Thombs BD. Reporting of conflicts of interest from drug trials in Cochrane reviews: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5155.

Bero LA. Why the Cochrane risk of bias tool should include funding source as a standard item. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;12:ED000075.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Standards for the reporting of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews Version 1.1 [updated 17 December 2012]. https://wounds.cochrane.org/sites/wounds.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/MECIR%20Reporting%20standards%201.1_17122012_2.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2020.

The Cochrane Collaboration. MECIR Manual [updated 5 April 2019]. https://community.cochrane.org/mecir-manual. Accessed 14 Feb 2020.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Drazen JM, Van Der Weyden MB, Sahni P, et al. Uniform format for disclosure of competing interests in ICMJE journals. JAMA. 2010;303(1):75–6.

Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7400):1167–70.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orange Book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/. Accessed 14 Feb 2020.

Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):873–90.

Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, Bauer DC, de Montmollin M, Aujesky D, Ford I, Gussekloo J, Kearney PM, Mooijaart S, Quinn T. Association of thyroid hormone therapy with quality of life and thyroid-related symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1349–59.

McIntyre WF, Um KJ, Alhazzani W, Lengyel AP, Hajjar L, Gordon AC, Lamontagne F, Healey JS, Whitlock RP, Belley-Côté EP. Association of vasopressin plus catecholamine vasopressors vs catecholamines alone with atrial fibrillation in patients with distributive shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1889–900.

Zheng SL, Roddick AJ, Aghar-Jaffar R, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis D, Oliver N, Meeran K. Association between use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors with all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1580–91.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JP, Egger M. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–66.

Gayet-Ageron A, Prieto-Merino D, Ker K, Shakur H, Ageron FX, Roberts I, Kayani A, Geer A, Ndungu B, Fawole B, Gilliam C. Effect of treatment delay on the effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytics in acute severe haemorrhage: a meta-analysis of individual patient-level data from 40 138 bleeding patients. Lancet. 2018;391(10116):125–32.

Jinatongthai P, Kongwatcharapong J, Foo CY, Phrommintikul A, Nathisuwan S, Thakkinstian A, Reid CM, Chaiyakunapruk N. Comparative efficacy and safety of reperfusion therapy with fibrinolytic agents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390(10096):747–59.

Alibhai SM, Zukotynski K, Walker-Dilks C, Emmenegger U, Finelli A, Morgan SC, Hotte SJ, Tomlinson GA, Winquist E. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for nonmetastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):341–50.

Wilson LM, Rebholz CM, Jirru E, Liu MC, Zhang A, Gayleard J, Chu Y, Robinson KA. Benefits and harms of osteoporosis medications in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):649–58.

Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, Khan N, Wang Z, Boyce L, Korenstein D. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

López-López JA, Sterne JA, Thom HH, Higgins JP, Hingorani AD, Okoli GN, Davies PA, Bodalia PN, Bryden PA, Welton NJ, Hollingworth W. Oral anticoagulants for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network meta-analysis, and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j5058.

Sadeghirad B, Siemieniuk RA, Brignardello-Petersen R, Papola D, Lytvyn L, Vandvik PO, Merglen A, Guyatt GH, Agoritsas T. Corticosteroids for treatment of sore throat: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2017;358:j3887.

McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, Richardson PG, Hulin C, Tosi P, Bringhen S, Musto P, Anderson KC, Caillot D, Gay F. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(29):3279.

van Beurden-Tan CH, Franken MG, Blommestein HM, Uyl-de Groot CA, Sonneveld P. Systematic literature review and network meta-analysis of treatment outcomes in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(12):1312–9.

Abdel-Qadir H, Ong G, Fazelzad R, Amir E, Lee DS, Thavendiranathan P, Tomlinson G. Interventions for preventing cardiomyopathy due to anthracyclines: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(3):628–33.

Siontis KC, Yao X, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease other than significant mitral stenosis and mechanical valves: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2017;135(7):714–6.

Renda G, Ricci F, Giugliano RP, De Caterina R. Non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):1363–71.

Lau ES, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Bonaca MP, Husted S, James SK, Wallentin L, Clemmensen P, Roe MT, Ohman EM. Potent P2Y12 inhibitors in men versus women: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(12):1549–59.

Verberkt CA, van den Beuken-van MH, Schols JM, Datla S, Dirksen CD, Johnson MJ, van Kuijk SM, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Respiratory adverse effects of opioids for breathlessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1701153.

Ding PN, Lord SJ, Gebski V, Links M, Bray V, Gralla RJ, Yang JC, Lee CK. Risk of treatment-related toxicities from EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a meta-analysis of clinical trials of gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib in advanced EGFR-mutated non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(4):633–43.

Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, Links M, Gebski V, Mok T, Yang JC. Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic EGFR-mutated non–small cell lung cancer—a meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):403–7.

Bethel MA, Patel RA, Merrill P, Lokhnygina Y, Buse JB, Mentz RJ, Pagidipati NJ, Chan JC, Gustavson SM, Iqbal N, Maggioni AP. Cardiovascular outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(2):105–13.

de Carvalho LS, Campos AM, Sposito AC. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis with over 96,000 patient-years. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(2):364–7.

Maiorino MI, Chiodini P, Bellastella G, Capuano A, Esposito K, Giugliano D. Insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist combination therapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(4):614–24.

Khera R, Pandey A, Chandar AK, Murad MH, Prokop LJ, Neeland IJ, Berry JD, Camilleri M, Singh S. Effects of weight-loss medications on cardiometabolic risk profiles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):1309–19.

Nelson AD, Camilleri M, Chirapongsathorn S, Vijayvargiya P, Valentin N, Shin A, Erwin PJ, Wang Z, Murad MH. Comparison of efficacy of pharmacological treatments for chronic idiopathic constipation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66(9):1611–22.

Ford AC, Luthra P, Tack J, Boeckxstaens GE, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Efficacy of psychotropic drugs in functional dyspepsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66(3):411–20.

Tenforde MW, Shapiro AE, Rouse B, Jarvis JN, Li T, Eshun-Wilson I, Ford N. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7.

McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7.

Normansell R, Sayer B, Waterson S, Dennett EJ, Del Forno M, Dunleavy A. Antibiotics for exacerbations of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6.

Turner KA, Carboni-Jiménez A, Benea C, Elder K, Levis B, Boruff J, Roseman M, Bero LA, Lexchin J, Turner EH, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Reporting of drug trial funding sources and author financial conflicts of interest in Cochrane and non-Cochrane meta-analyses: a cross-sectional study. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9zf7y.

Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Tricco AC, Sampson M, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e78.

Moja LP, Telaro E, D'amico R, Moschetti I, Coe L, Liberati A. Assessment of methodological quality of primary studies by systematic reviews: results of the metaquality cross sectional study. BMJ. 2005;330(7499):1053.

Wen J, Ren Y, Wang L, Li Y, Liu Y, Zhou M, Liu P, Ye L, Li Y, Tian W. The reporting quality of meta-analyses improves: a random sampling study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(8):770–5.

Standards for the reporting of new Cochrane Interventions. http://www.prisma-statement.org/News. February 14, 2020.

Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: a scoping review. Sys Rev. 2017;6:263.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Sterne JA. Why the Cochrane risk of bias tool should not include funding source as a standard item. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12.

Lundh, A. Tool for Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Trials (TACIT) in Cochrane Reviews [PowerPoint slides]. 2018. https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/sites/methods.cochrane.org.bias/files/public/uploads/andreas_lundh_tacit.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2020.

Funding

Dr. Thombs was supported by a Fonds de Recherche Québec - Santé (FRQ-S) researcher award, and Ms. Turner was supported by a FRQ-S masters training award, both outside of the submitted work. There was no sponsor involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BDT had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MR, LAB, JL, EHT, and BDT contributed to the study concept and design. CB, MR, KAT, LB, JL, EHT, and BDT contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. CB, KAT, and BDT drafted the manuscript. CB, KAT, MR, LAB, JL, EHT, and BDT critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. BDT contributed to the statistical analysis. BDT supervised the study. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Bero disclosed that she is Senior Editor, Cochrane Public Health and Health Systems, for which the University of Sydney receives remuneration. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

Methods 1. Title/Abstract and Full Text Eligibility Coding Guide.

Additional file 2:.

Methods 2. Meta-Analysis Data Extraction.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Benea, C., Turner, K.A., Roseman, M. et al. Reporting of financial conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of drug trials published in high-impact medical journals: comparison of results from 2017 to 2018 and 2009. Syst Rev 9, 77 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01318-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01318-5