Abstract

Background

Of various chronic diseases, low back pain (LBP) is the most common and debilitating musculoskeletal condition among older adults aged 65 years or older. While more than 17 million older adults in the USA suffer from at least one episode of LBP annually, approximately six million of them experience chronic LBP that significantly affects their quality of life and physical function. Since many older adults with chronic LBP may also have comorbidities and are more sensitive to pain than younger counterparts, these older individuals may face unique age-related physical and psychosocial problems. While some qualitative research studies have investigated the life experiences of older adults with chronic LBP, no systematic review has integrated and synthesized the scientific knowledge regarding the influence of chronic LBP on the physical, psychological, and social aspects of lives in older adults. Without such information, it may result in unmet care needs and ineffective interventions for this vulnerable group. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review is to synthesize knowledge regarding older adults’ experiences of living with chronic LBP and the implications on their daily lives.

Methods/design

Candidate publications will be sought from databases: PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Qualitative research studies will be included if they are related to the experiences of older adults with chronic LBP. Two independent reviewers will screen the titles, abstracts, and full-text articles for eligibility. The reference lists of the included studies will be checked for additional relevant studies. Forward citation tracking will be conducted. Meta-ethnography will be chosen to synthesize the data from the included studies. Specifically, the second-order concepts that are deemed to be translatable by two independent reviewers will be included and synthesized to capture the core of the idiomatic translations (i.e., a translation focusing on salient categories of meaning rather than the literal translation of words or phrases).

Discussion

This systematic review of qualitative evidence will enable researchers to identify potential unmet care needs, as well as to facilitate the development of effective, appropriate, person-centered health care interventions targeting this group of individuals.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO 2018: CRD42018091292

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The average human life expectancy has increased significantly worldwide due to advances in medicine, health care delivery, and technologies over the recent years [1]. The The United Nations has estimated that the global population of people aged 60 or over will triple by 2050 [2]. The fast-growing aging population is accompanied by multiple health issues (e.g., musculoskeletal pain). It has been estimated that approximately 65 to 85% of older adults are suffering from musculoskeletal pain [3, 4].

Of various musculoskeletal pain, low back pain (LBP) is the most prevailing health condition in older adults that leads to functional limitations and disability [5,6,7]. LBP is defined as pain or discomfort between the 12th rib and above the gluteal sulcus with or without radiating leg pain [8]. More than 17 million older adults in the USA suffer from at least one episode of LBP annually [9]. Similarly, multiple population-based studies have found that the prevalence of LBP (regardless of chronicity) among community-dwelling older adults in the last 12 months ranged from 13 to 50% [3, 10,11,12]. Since the prevalence of chronic LBP increases with age [13,14,15], many older adults experience chronic LBP that lasts for at least 3 months [16, 17]. It has been estimated that prevalence rates of chronic LBP in individuals aged 60 years or older were approximately 30% in different parts of the world [12, 18]. In the USA alone, over six million older adults experienced chronic LBP that significantly compromised their quality of life and physical function. [9]. Importantly, since chronic LBP is the major contributor of disability (including falls [19]) in older adults [20, 21], its negative impacts extend beyond the patients. Chronic LBP (like other chronic pain) imposes severe financial burden to caregivers and society [22] although the direct impact of LBP on work productivity in retired older adults appears minimal.

Older adults with LBP face unique age-related vulnerabilities. Compared to younger individuals, older adults are more sensitive to pain because of the compromised endogenous pain modulation processing [23, 24] and decreased pain thresholds [25]. Additionally, comorbidities in older adults (e.g., cognitive impairment [26], polypharmacy [27], and multisource pain generation [28]) may potentiate the debilitating effects of chronic LBP [29], reduce patients’ adherence to medical and therapeutic interventions, and/or cause contraindications to LBP treatments [30]. Since older adults may also need to face multiple age-related psychosocial comorbidities (e.g., bereavement from the loss of spouse or friends, financial constraints, depression and social isolation [31,32,33]), these factors can negatively affect their LBP recovery, LBP-related disability, and attitudes/beliefs about pain [34].

Given the high prevalence of debilitating chronic LBP in older adults, designing and implementing proper age-related pain interventions has been suggested to be one of the priorities for educating healthcare professionals [35]. Although multidisciplinary chronic pain management approaches that incorporate the physician’s, nurse’s, and social worker’s perspectives have been recommended for treating older adults with chronic pain [36], patients’ perspective on their chronic LBP experiences is less emphasized in existing pain management guidelines [37]. Since chronic LBP can disrupt older adults’ life, as well as their family’s life and/or social relationships [36], it is paramount to look beyond medical treatments for these individuals so that more comprehensive approaches (e.g., the provision of supportive services or spouse participation) can be formulated to address age-related needs. For instance, a qualitative study interviewing a group of older adults with chronic pain living in rural Thailand revealed that these patients were more likely to adopt self-management programs when treatment for pain reduction or related information was more accessible, affordable, and acceptable [38]. Such information can inform the effective allocation of resources to meet patients’ needs.

While quantitative studies usually use theoretical-based self-reported questionnaires to evaluate the pain and function of older adults with chronic LBP [39], these studies are unable to determine the in-depth concerns or feeling of older adults with chronic LBP [40], which can explain patients’ behaviors and may better inform health and social policy for these patients. This limitation can be addressed by qualitative research. For instance, qualitative studies can provide insights into how age-related social roles can affect the older adults’ experiences with LBP. Therefore, a growing number of qualitative studies have been conducted to investigate the impacts of chronic LBP on various facets of life (e.g., coping strategies and social roles) in older adults residing in different settings [41,42,43,44,45,46]. However, no systematic review of qualitative studies has ever been conducted, and we propose to utilize qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) to integrate these research findings. Since age, gender, social class, levels of education, culture, and living environments may have differential influences on the perceived impacts of chronic LBP in older adults, QES can be applied to re-interpret the conceptual data from primary studies [47] in order to deepen the understanding of how chronic LBP impacts the life experience of older adults. Furthermore, QES can enrich the relevance of findings from multiple qualitative studies, thereby broadening the perspectives [48] and enabling to inform healthcare policy or practice [49].

Given the above, the overarching objective of this systematic review of qualitative research is to synthesize and conceptualize daily life experience of older adults living with chronic LBP. It will pose two specific questions to the included studies:

-

What concepts concerning older adults’ experiences of daily life, when living with chronic LBP, can be identified?

-

How can the identified concepts be understood (i.e., conceptually clarified)?

Method/design

Meta-synthesis is often used as an overarching umbrella term for describing different methods of qualitative evidence synthesis. Meta-ethnography [50], the approach used in the current review, is the most commonly cited method in health service research to synthesize findings from studies with a qualitative design. Our rationale for conducting a meta-ethnography, instead than for example a thematic analysis, is that it is an interpretative rather than an aggregate form of knowledge synthesis. Accordingly, it aims to develop a conceptual understanding of the phenomenon [50].

Search strategies

The search strategy, design, and structure for this meta-synthesis was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement for protocols [51] (Additional file 1). A thorough search strategy will be developed using the SPICE (setting, population/perspective, intervention, composition, and evaluation) tool [52, 53], which will help formulate search terms for qualitative research studies with appropriate sample and phenomenon of interest (Table 1). An initial scoping search has been conducted on PubMed to understand how studies are indexed and what terms to use in searching titles and abstracts (Additional file 2). There was no date range limitation for the search. The initial search also aimed to check the suitability of the method of review and review questions and to estimate the number of expected citations for screening [54, 55]. The search supported the feasibility of formulating our tentative review questions, as well as the suitability of our method of synthesis (i.e., meta-ethnography).

Potential studies will be searched from PubMed (Additional file 3), PsycINFO, and CINAHL, acknowledged to cover the important quantity of health service research, by using keywords and their equivalent subject headings (e.g., Medical Subject Headings or CINAHL Subject Headings). Three search strings will be included: (chronic low* back pain OR chronic LBP OR CLBP OR chronic backache OR chronic non-specific low back pain OR chronic non-specific LBP OR lumbar pain OR lumbago) AND (qualitative study OR qualitative research OR action research OR ethnographic research OR grounded theory OR phenomenological research OR naturalistic inquiry OR focus group OR interview OR narrative) AND (older adults OR old people OR older persons OR older individuals OR geriatric OR seniors OR elderly). Adjacent syntax (older adj2 adult*) will also be used to identify papers involving older adults. A manual search of reference lists of the included studies will be performed. Forward citation tracking will be conducted using Scopus to identify additional relevant articles that were cited in the included studies.

Selection of studies

Studies will be included if they (i) are in English, French, German, Spanish, Swedish, or Chinese; (ii) are published in peer-reviewed journals; (iii) used qualitative methods and a qualitative analysis; (iv) included participants aged 65 years and older regardless of study context; and (v) report on the experience of older adults with chronic nonspecific LBP. The latter is defined as pain in or near the lumbosacral spine with or without radiating leg pain that lasts for at least 3 months unrelated to osteoporosis, infection, tumor, fracture, cauda equina syndrome, and inflammatory disorders. There will be no limitations regarding the types of qualitative designs in the current meta-ethnography based on the suggestion from studies discussing the methodology of meta-ethnography [56, 57].

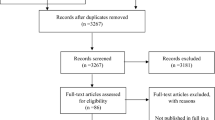

Studies will be excluded if (i) they used mixed methods where qualitative data cannot be extracted or (ii) the data analysis lacks the necessary conceptual depth (i.e., assessed as containing only non-translatable second-order concepts) [58]. A two-stage screening approach will be used. At the first stage, two independent reviewers (AW and GB) will screen titles and abstracts for the selection of articles for full-text screening. Any disagreement between the two reviewers will be resolved through discussion. If disagreement persists, the article under scrutiny will be included for full-text screening. At the second stage, all selected full-text articles will be retrieved. The same reviewers will use the previously applied selection criteria to perform full-text screening. Any disagreements will first be resolved through discussion, and if it persists, a third reviewer will make the decision for inclusion or exclusion of articles.

Data extraction and data synthesis

This study will adopt an inclusive approach to extract data. Specifically, reviewers will extract all relevant data presented in a study using a standard form developed based on the suggestions from Toye et al. [58]. The extracted data will include study objectives, study design, authors, year of publication, context, sample size and demographics (gender, age, living circumstances), data collection methods, data analysis, and clearly articulated second-order constructs (e.g., concepts). Notably, second-order constructs, together with the text underpinning the construct, will be extracted. According to Schutz [59], a first-order construct is the phenomenon/experience perceived by the participants. A second-order construct is the researchers’ interpretation of the participants’ first-order constructs. In this review, all extracted concepts should explain the data (i.e., to be translatable). Two independent reviewers will exclude all second-order concepts that are deemed to be non-translatable or are irrelevant to the review questions. According to Toye and colleagues [58], this is a useful strategy for interpreting data of qualitative studies. Any disagreements between the two reviewers in regard to second-order concepts will be discussed with the research team, whereas a third reviewer will be consulted if disagreements among reviewers persist.

The extracted second-order constructs and their underpinning text will subsequently be transferred to a Word document (i.e., to a synthesis matrix). The latter will contain free space for the non-linear process of condensing the supporting content into idiomatic translations (i.e., translations focusing on salient categories of meaning rather than the literal translations of words or phrases [60]). According to Campbell and colleagues (2011), it is the translated data that gets synthesized so that a full understanding of the concepts can be reached [61]. The matrix will assist in identifying similarities and differences within and across included studies. Lines-of-argument (LOA) synthesis will be used to capture the core of the idiomatic translation. Specifically, the LOA synthesis will help interpret various translatable concepts within and across studies to construct the main core meaning (i.e., provide an overarching conceptual understanding) [60].

Assessment of the methodological quality of included studies

In this review, methodological quality appraisal of the included studies will be conducted by the two independent reviewers because it is important to account for study quality when evaluating their overall influences on the end results. The appraisal is influenced by Toye et al.’s [58] conceptual model to quality appraisal, which suggested two core facets of quality for inclusion in meta-ethnography: (1) conceptual clarity (the clarity of the authors in articulating a concept that facilitates theoretical insight) and (2) interpretive rigor (what is the context of the interpretation; how inductive are the findings; has the interpretation been challenged?). The research team will develop an appraisal sheet in accordance with Toye et al.’s [58] conceptual model. The included studies will then be categorized as either a key paper, satisfactory paper, fatally flawed paper, or an irrelevant paper. If there are any disagreements between the two reviewers, a third reviewer will be consulted for decision-making. Our experience from previously conducted meta-ethnographies has shown that a study can be deemed as fatally flawed methodologically but it can still provide interesting and rich insights (Authors, under review). Therefore, we will include conceptually rich studies even when the methodological quality may be suboptimal. A sensitivity analysis of findings based on the quality of the included studies will be conducted [58].

Discussion

Since the current systematic review aims to encompass relevant qualitative research papers related to experiences of older adults with chronic LBP, it will be a comprehensive benchmark review paper in the field. The findings not only will provide an overview of all relevant qualitative research areas but also will identify research gaps for future studies and can be used as a foundation for developing adequate assessments and/or interventions for older adults with chronic LBP. Specifically, this review will significantly contribute to the holistic management of chronic LBP in older adults by (1) integrating and synthesizing existing qualitative research findings related to chronic LBP experiences of older adults residing in different settings; (2) providing an in-depth knowledge with regard to older adults’ experiences of living with chronic LBP and the implications on daily life; and (3) identifying potential unmet care needs of this population so that more effective person-centered healthcare and social interventions can be developed/implemented. The findings emerging from the proposed project will subsequently form the theoretical and empirical basis for designing a research program to investigate the effectiveness, adequacy, and feasibility of culturally competent interprofessional allied health interventions in improving the health and independence of living in older people with chronic LBP.

Abbreviations

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- SPICE:

-

Setting, population or perspective, intervention, composition, and evaluation

References

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2016.

DoEaSA UN. World population ageing 2009. New York: United Nations Publication; 2010.

Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly: a systematic review of the literature. Spine. 1999;24:1813–9.

Podichetty VK, Mazanec DJ, Biscup RS. Chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain in older adults: clinical issues and opioid intervention. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:627–33.

Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, Gutierrez Robledo LM, O’Donnell M, Sullivan R, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet. 2015;385:549–62.

Palacios-Ceña D, Alonso-Blanco C, Hernández-Barrera V, Carrasco-Garrido P, Jiménez-García R, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Prevalence of neck and low back pain in community-dwelling adults in Spain: an updated population-based national study (2009/10–2011/12). Eur Spine J. 2015;24:482–92.

Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Hernández-Barrera V, Palacios-Ceña D, Jiménez-García R, Carrasco-Garrido P. Has the prevalence of neck pain and low back pain changed over the last 5 years? A population-based national study in Spain. Spine J. 2013;13:1069–76.

Wong AYL, Kawchuk G, Parent E, Prasad N. Within- and between-day reliability of spinal stiffness measurements obtained using a computer controlled mechanical indenter in individuals with and without low back pain. Man Ther. 2013;18:395–402.

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;41:778–99.

Leopoldino AAO, Diz JBM, Martins VT, Henschke N, Pereira LSM, Dias RC, et al. Prevalence of low back pain in older Brazilians: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition). 2016;56:258–69.

Woo J, Leung J, Lau E. Prevalence and correlates of musculoskeletal pain in Chinese elderly and the impact on 4-year physical function and quality of life. Public Health. 2009;123:549–56.

Patel KV, Guralnik JM, Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Pain. 2013;154:2649–57.

Di Iorio A, Abate M, Guralnik JM, Bandinelli S, Cecchi F, Cherubini A, et al. From chronic low back pain to disability, a multifactorial mediated pathway: the InCHIANTI study. Spine. 2007;32:E809–15.

Rudy TE, Weiner DK, Lieber SJ, Slaboda J, Boston JR. The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults: a comparative study of patients and controls. Pain. 2007;131:293–301.

Jiménez-Sánchez S, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Carrasco-Garrido P, Hernández-Barrera V, Alonso-Blanco C, Palacios-Ceña D, et al. Prevalence of chronic head, neck and low back pain and associated factors in women residing in the autonomous region of Madrid (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2012;26:534–40.

Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581–5.

Wong AY, Karppinen J, Samartzis D. Low back pain in older adults: risk factors, management options and future directions. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017;12:14.

Wong WS, Fielding R. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the general population of Hong Kong. J Pain. 2011;12:236–45.

Hulla R, Moomey M, Garner T, Ray C, Gatchel R. Biopsychosocial characteristics, using a new functional measure of balance, of an elderly population with CLBP. Healthcare. 2016;4:59.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, Vos T, et al. Measuring the global burden of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:155–65.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–74.

Institute of Medicine US Committee on Advancing Pain Research. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington (DC): National Academic Press (US); 2011.

Cole LJ, Farrell MJ, Gibson SJ, Egan GF. Age-related differences in pain sensitivity and regional brain activity evoked by noxious pressure. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:494–503.

Edwards RR, Fillingim RB, Ness TJ. Age-related differences in endogenous pain modulation: a comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in healthy older and younger adults. Pain. 2003;101:155–65.

Lautenbacher S, Kunz M, Strate P, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L. Age effects on pain thresholds, temporal summation and spatial summation of heat and pressure pain. Pain. 2005;115:410–8.

Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30:421–42.

Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2261–72.

Weiner DK, Sakamoto S, Perera S, Breuer P. Chronic low back pain in older adults: prevalence, reliability, and validity of physical examination findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:11–20.

Williams JS, Ng N, Peltzer K, Yawson A, Biritwum R, Maximova T, et al. Risk factors and disability associated with low back pain in older adults in low- and middle-income countries. Results from the WHO Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127880.

Scherer M, Hansen H, Gensichen J, Mergenthal K, Riedel-Heller S, Weyerer S, et al. Association between multimorbidity patterns and chronic pain in elderly primary care patients: a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:68.

Gong F, Zhao D, Zhao Y, Lu S, Qian Z, Sun Y. The factors associated with geriatric depression in rural China: stratified by household structure. Psychol Health Med. 2017;32:1–11.

Volkert J, Schulz H, Härter M, Wlodarczyk O, Andreas S. The prevalence of mental disorders in older people in western countries—a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:339–53.

Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–91.

Meyer T, Cooper J, Raspe H. Disabling low back pain and depressive symptoms in the community-dwelling elderly: a prospective study. Spine. 2007;32:2380–6.

Herr K. Pain in the older adult: an imperative across all health care settings. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11:S1–10.

Reid MC, Eccleston C, Pillemer K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h532.

Lansbury G. Chronic pain management: a qualitative study of elderly people’s preferred coping strategies and barriers to management. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;22:2–14.

Panpanit L, Carolan-Olah M, McCann TV. A qualitative study of older adults seeking appropriate treatment to self-manage their chronic pain in rural North-East Thailand. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:166.

Tse MMY, Lai C, Lui JYW, Kwong E, Yeung SY. Frailty, pain and psychological variables among older adults living in Hong Kong nursing homes: can we do better to address multimorbidities? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23:303–11.

Gold DT, Roberto KA. Correlates and consequences of chronic pain in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2000;21:270–3.

Bailly F, Foltz V, Rozenberg S, Fautrel B, Gossec L. The impact of chronic low back pain is partly related to loss of social role: a qualitative study. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82:437–41.

Lyons KJ, Salsbury SA, Hondras MA, Jones ME, Andresen AA, Goertz CM. Perspectives of older adults on co-management of low back pain by doctors of chiropractic and family medicine physicians: a focus group study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:225.

Sofaer-Bennett B, Walker J, Moore A, Lamberty J, Thorp T, O’Dwyer J. The social consequences for older people of neuropathic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2007;8:263–70.

Lansbury G. Chronic pain management: a qualitative study of elderly people’s preferred coping strategies and barriers to management. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22:2–14.

Makris UE, Higashi RT, Marks EG, Fraenkel L, Sale JEM, Gill TM, et al. Ageism, negative attitudes, and competing co-morbidities - why older adults may not seek care for restricting back pain: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:39.

Makris UE, Higashi RT, Marks EG, Fraenkel L, Gill TM, Friedly JL, et al. Physical, emotional, and social impacts of restricting back pain in older adults: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2017;18:1225–35.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1:28.

Levack WMM. The role of qualitative metasynthesis in evidence-based physical therapy. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17:390–7.

Hannes K, Lockwood C. Synthesizing qualitative research. Chichester: Wiley; 2011.

Nobit GW, Dwight HR. Meta-ethnography synthesizing qualitative studies. Qualitative research method series. California: Sage Publication, Inc; 1988.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Booth A. Formulating answerable questions. In:Evidence-Based Practice for Information Professionals: A Handbook.Andrew Booth and Anne Brice, editors. London: Facet Publishing; 2004.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO; the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1435–43.

Abad-Corpa E, Gonzalez-Gil T, Barderas-Manchado AM, la Cuesta-Benjumea de C, Monistrol-Ruano O, Mahtani-Chugani V, et al. Research protocol: a synthesis of qualitative studies on the process of adaptation to dependency in elderly persons and their families. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:58.

Shaw RL, Booth A, Sutton AJ, Miller T, Smith JA, Young B, et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:5.

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;7:209–15.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:671–84.

Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Andrews J, et al. “Trying to pin down jelly”—exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:46.

Schutz A, Collected Papers I. In: Natanson M, editor. The problem of social reality. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff; 1973.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker-White G, Britten N, Pill R, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:1–164.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Carina Olsson and Ms. Lisa Farare, librarians at Malmo University, for assisting the development of a search strategy for this project.

Funding

This study was funded by the Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö University, and the Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Collaborative Research Grants Scheme (Ref number: 1-ZVJZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW and GB were responsible for the study inception and design. AW and GB were responsible for the data acquisition and drafting the initial manuscript. AW, GB, KSF, JJ, VS, and CK will perform the data extraction and analysis. All authors were responsible for the critical revision of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Dr. AW is an assistant professor at the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Hong Kong, SAR, China. Drs. KSF and JJ are both senior lecturers at the Department of Care Science, Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö University, Sweden. Dr. VS is an assistant professor at the at the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Hong Kong, SAR, China. Dr. CK is a professor in Nursing at Malmö University, Department of Care Sciences, Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö Sweden. Dr. GB is a reader in Nursing at Malmö University, Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö Sweden.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since the current meta-ethnography will not involve any human participants, no ethics approval is needed. This study will be conducted in compliance with the established ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki [62].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Prisma-P checklist. (DOCX 30 kb)

Additional file 2:

Overview search filters PubMed. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 3:

Search string PubMed. (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, A.Y.L., Forss, K.S., Jakobsson, J. et al. Older adult’s experience of chronic low back pain and its implications on their daily life: Study protocol of a systematic review of qualitative research. Syst Rev 7, 81 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0742-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0742-5