Abstract

Background

Information-seeking behaviour is necessary to improve knowledge on diabetes therapy and complications. Combined with other self-management skills and autonomous handling of the disease, it is essential for achieving treatment targets. However, a systematic review addressing this topic is lacking. The aims of this systematic review were to identify and analyse existing knowledge of information-seeking behaviour: (1) types information-seeking behaviour, (2) information sources, (3) the content of searched information, and (4) associated variables that may affect information-seeking behaviour.

Methods

The systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) requirements. MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, ScienceDirect, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CCMed, ERIC, Journals@OVID, Deutsches Ärzteblatt and Karlsruher virtueller Katalog (KvK) databases were searched. Publications dealing with information-seeking behaviour of people with diabetes mellitus published up to June 2015 were included. A forward citation tracking was performed in September 2016 and June 2017. Additionally, an update of the two main databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL) was conducted, considering studies published up to July 2017. Studies published in languages other than English or German were excluded, as well as letters, short reports, editorials, comments and discussion papers. A study selection and the critical appraisal of the selected studies were performed independently by two reviewers. A third reviewer was consulted if any disagreement was found. Data extraction and content analysis were performed using selected dimensions of Wilson’s ‘model of information behaviour’.

Results

Twenty-six studies were included. Five ‘types of information-seeking behaviour’ were identified, e.g. passive and active search. The ‘Internet’ and ‘healthcare professionals’ were the most frequently reported sources. ‘Diet’, ‘complications’, ‘exercise’ and ‘medications and pharmacological interactions’ were the most frequently identified content of information. Seven main categories including associated variables were identified, e.g. ‘socioeconomic’, ‘duration of DM’, and ‘lifestyle’.

Conclusion

The systematic review provides a valuable overview of available knowledge on the information-seeking behaviour of people with diabetes mellitus, although there are only a few studies. There was a high heterogeneity regarding the research question, design, methods and participants. Although the Internet is often used to seek information, health professionals still play an important role in supporting their patients’ information-seeking behaviour. Specific needs of people with diabetes must be taken into consideration.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016037312

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2013, it was estimated that 382 million adults (18–79 years) worldwide had diabetes mellitus (DM), and this number is expected to rise to 592 million in 2035 [1]. DM is associated with high healthcare costs and comorbidities that can result in individual restrictions and in a reduced quality of life [2,3,4]. In this regard, the International Diabetes Federation estimated the costs of DM treatment in Europe at US$290 billion in 2015 [4].

Self-management is essential in achieving treatment targets, as is indicated by the outcomes of clinical studies regarding the percentage of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c%) or blood pressure control [5]. An important aspect of self-management is patients’ knowledge, including their ability to seek information [6]. Information-seeking behaviour is one component of information behaviour along with handling sources and channels and using information. Wilson’s ‘model of information behaviour’ describes information seeking and use as direct consequences of information need [7], and characterises ‘types of information seeking’ and its related ‘intervening variables’ and considers ‘activating mechanism’ based on several psychological and social theories [8]. Within this context, this review focuses on information-seeking behaviour that is defined as ‘the purposive seeking for information as a consequence of a need to satisfy some goal’ [7]. According to Wilson’s model, there are four different types of information-seeking behaviour: passive attention, passive or active searching and ongoing search [8]. Passive attention is obtaining information without intending to look for it (e.g. watching television). Passive searching is finding relevant information while searching for other topics of information. This usually leads to active searching, ‘the principal mode’ in the process of information seeking, where ‘an individual actively seeks out information’ [8]. The last mode is ‘ongoing search’, which is performed during active search to update or to expand present information [8]. The intervening variables that are associated with information-seeking behaviour are ‘psychological’, ‘demographic’, ‘role-related or interpersonal’, ‘environmental’ variables and ‘source characteristics’ (e.g. currency, appropriateness) [8].

Research into information-seeking behaviour among people with DM appears to be limited so far, despite the fact that studies have demonstrated that information-seeking behaviour is crucial in enabling people to cope with the consequences of their disease [5]. Although there are some publications concerning information-seeking behaviour among individuals with DM [5, 9, 10], to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has yet analysed knowledge on information-seeking behaviour. An overview of the information-seeking behaviour of people with DM is needed to develop recommendations for practice and research in order to guarantee the necessary support for handling information on diabetes.

The aims of this systematic review were to identify and analyse existing knowledge of information-seeking behaviour: (1) types of information-seeking behaviour, (2) information sources, (3) the content of searched information, and (4) associated variables, which may affect the information-seeking behaviour of people with all types of DM.

Methods

A systematic review was performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) quality requirements [11] and is registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42016037312). A systematic review protocol was developed that guided the review process (Additional file 1).

Search strategy

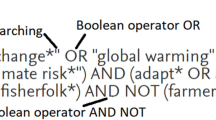

The systematic literature search was performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CCMed, ERIC, Journals@OVID, DARE, ISI and EED. German sources were also searched: Deutsches Ärzteblatt and Karlsruher virtueller Katalog (KvK). Studies published up to June 2015 were considered. Additionally, an update of the two core databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL) was conducted, including studies published up to July 2017. The search strategy was developed using database-specific controlled vocabularies and free-text terms (Additional file 2). The search terms included for DM were, among others, ‘diabetes mellitus’, ‘diabetes mellitus, Type 1/Type 2’, ‘diabetic’, ‘niddm’, ‘iddm’, ‘t2dm’ and ‘t1dm’. The search terms included for information-seeking behaviour were, among others, ‘information-seeking behaviour’, ‘information behaviour’ and ‘isb’. Duplicates of all databases were removed. A forward citation tracking was performed in September 2016 and June 2017 to identify further relevant studies in Google Scholar by searching citations of already identified core publications [5, 12, 13]. Google Scholar locates articles by using a matching algorithm and searching keywords in title, abstract or full text [14].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review included quantitative studies as well as qualitative and mixed-methods studies, also sourced from grey literature such as dissertations. Publications considering people with DM and diabetes-related information-seeking behaviour were included that used the following terms in different combinations and their synonyms, e.g. information-seeking behaviour and/or information seeking, information search and/or seek for information.

Studies published in languages other than English or German were excluded, as well as letters, short reports, editorials, comments and discussion papers. However, they were used to find further studies.

There were no exclusion criteria concerning the type of diabetes or the assessment tools used to collect data about information-seeking behaviour. None of the studies were excluded because of their low quality.

Study selection process

A pre-test for the title and abstract screening was performed, which included 100 articles selected by three reviewers. Potentially eligible publications were selected by their title and abstract and categorised into ‘included’, ‘unclear’ and ‘excluded’. Literature identified by title and abstract and labelled as ‘included’ or ‘unclear’ was screened as full texts and analysed for final inclusion. Two raters reviewed independently each step and a third reviewer resolved unclear coding.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed according primarily to Wilson’s ‘model of information behaviour’ as described above (Table 1).

However, two adjustments were made: (1) since information sources are implicitly described in the definitions of information-seeking behaviour [7], it was defined as an additional main category (instead of an associated variable). The preferred sources for gaining information, such as the Internet, television and health professionals, were subdivided. (2) A further main category was also introduced, namely content of information, since it is one of the main questions of the review.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis (narrative synthesis) was performed in accordance with the Cochrane methods for data analysis and syntheses [15], which is in line with the “Best-fit” framework synthesis as described by Carroll et al. [16], except the adjustment of the model, which was not the aim of our review.

Qualitative and quantitative data, including data from mixed-methods studies, were described, analysed separately and grouped. The characteristics of the studies and important differences between them were described systematically. The results were then tabulated. Relevant topics were highlighted and data transformed into a descriptive format. The results from the content analysis were described by summarising similar findings regarding information-seeking behaviour and associated variables from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies. Deductive and inductive content analyses were performed [17, 18]. Deductive categories were derived from Wilson’s model (Table 1), including the adjustments, and inductive categories or subcategories from the included publications. Several steps were performed for the inductive approach [17, 18]. The first step was to identify relevant data segments from the included studies. The second step was to develop data matrices including raw data, first codes and memos. The third step was to arrange similar memos together and to find categories into which the corresponding segments fitted. This step was repeated and re-evaluated several times. A combined coding protocol and data extraction sheet was developed for the deductive and inductive categories.

Critical appraisal and risk of bias

Qualitative and quantitative studies were analysed using the quality criteria of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [19], using a coherent set of critical appraisals. These NICE appraisal checklists were developed to assess the risk of bias in diverse types of studies [19]. The degree of bias risk can be determined at the end of the appraisal process.

Quality criteria include factors such as whether the study population is well described and whether it is representative, how explanatory variables were selected, how the confounding factors were identified and controlled, whether the outcome measures were reliable or complete, whether the power was calculated and multiple explanatory variables were considered, whether the precision of the association was provided, and whether the studies were internally or externally valid for quantitative studies [19]. For qualitative studies, quality criteria regarding the methods were, for example, whether the qualitative approach was appropriate, the study aim was clear, the research design and methodology were defensible, how well data collection was performed, whether the researchers’ role and the context were clearly described, whether the methods were reliable, and whether the data analysis was sufficiently rigorous as well as reliable. Additional criteria for apprising the results and conclusions were, for example, whether the data was rich, relevant, the findings convincing and the conclusions adequate [19]. According to NICE grading, the study’s quality was described as follows: ‘(++) all or most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled the conclusions are very unlikely to alter; (+) some of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled, or not adequately described, the conclusions are unlikely to alter; (-) few or no checklist criteria have been fulfilled and the conclusions are likely or very likely to alter’ [19].

Criteria from the “Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)” for mixed-methods studies include whether the mixed-methods design was appropriate, the integration was relevant to address the research question (objective) and whether the consideration given to the limitations associated with this integration, e.g. the divergence of qualitative and quantitative data (or results) in a triangulation design, was appropriate [20, 21]. The study quality was described by fulfilled or not fulfilled criteria [20, 21]. Two raters performed independently the critical appraisal and then resolved differences, if necessary.

Results

A total of 2285 hits were identified. Finally, 28 publications (covering 26 studies) were included, of which 17 studies (covering 18 publications) were found by searching for studies published up to June 2015 [5, 9, 10, 12, 13, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] and two publications [35, 36] by forward citation tracking of which one study was new [36] and one was already identified in the first search process. Additionally, eight further studies (covering eight publications) were identified by updating the search in July 2017 [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] (see Fig. 1). The 26 selected studies comprise the following: one by forward citation tracking, 10 applied qualitative methods [9, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 37, 39, 40], 12 applied quantitative methods [5, 10, 22,23,24,25,26, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44] and four mixed-methods [12, 33, 34, 43].

The studies investigated information-seeking behaviour, applied for example semi-standardised questionnaires [32, 34, 37, 43], interviews with open-ended questions [12, 28, 30, 31, 33, 39, 43] and focus groups [9, 27, 29, 31, 40].

The sample sizes of the participants with DM of the studies ranged from n = 12 [40] to n = 3652 [41]. Most of the studies (n = 25) provided information about gender, age and the region participants were recruited from. Three studies [34, 39, 42] included only female participants because they focussed on DM and pregnancy. Most of the studies included adults, and only one focused on younger people with DM [23]. Participants were mostly recruited from Europe (n = 10) [5, 22,23,24, 29, 31, 34, 37, 38, 43] or North America (n = 6) [9, 12, 25, 27, 30, 33], while five studies took place in Asia [26, 28, 36, 40, 44], three in Australia [39, 41, 42] and one in Canada [10]. The region of one study is unknown [32]. An overview of the included studies is presented in Table 2.

Types of DM were specified in 23 studies: 11 studies included participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [10, 12, 25, 28,29,30,31, 36, 40, 41, 43], four included participants with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) [23, 26, 34, 38], five included participants with T1DM and T2DM [5, 9, 24, 32, 33], two with gestational diabetes (GDM) [39, 42] and one study included participants with prediabetes [22]. One study included people with T2DM as well as people with prediabetes and GDM [44].

Five studies provided specifications about the minimum duration of the diagnosis of DM [23, 26, 28, 33, 38], and six studies provided information on HbA1c% [5, 12, 26, 38, 41, 43] and five on body mass index (BMI) [22, 26, 27, 39, 41].

Only four studies provided a clear definition of ‘information-seeking behaviour’. It is seen in the context of health information behaviour, consisting of ‘health-related information needs, information seeking, and information use’ [12]. Longo et al. describes it as consisting of ‘active information seeking’, with the aim of acquiring specific information for an intended purpose with a ‘passive receipt of information’ where information is gained ‘unintentionally’ [9]. Moonaghi et al. provides an extended explanation by describing it as being ‘influenced by peoples’ perceptions about a disease within the context of traditional and cultural beliefs and attitudes’. Furthermore, information seeking is outlined ‘as a key coping strategy in health-promotion activities and in the psychosocial adjustment to illness’ [28]. Zare-Farashbandi et al. defined that ‘Health information-seeking behaviours of a person include search, discovery, and use of information related to diseases, health-threatening factors, and health care’ [44].

The critical appraisal performed showed that only three of the 28 publications (covering 26 studies) identified fulfilled all or most of the checklist criteria of NICE or MMAT. In accordance with the NICE grading system, the other publications fulfilled some (n = 14) or a few (n = 5) of the quality criteria and displayed a higher level of bias [19] (Table 2).

Information-seeking behaviour: type, sources and content

In total, five types of information-seeking behaviours were identified (Table 3), namely ‘passive attention’ (n = 4) [9, 28, 30, 44], ‘passive search’ (n = 2) [29, 30], ‘active search’ (n = 7) [9, 12, 28,29,30,31, 35, 44] and ‘ongoing search’ (n = 4) [9, 12, 28, 29] as defined in Wilson’s model and an additional ‘combined search types’ (n = 6) category [9, 12, 28, 29, 31, 32]. For example, one study reported that the information-seeking process began with a more general approach and became more specific [12].

Nine inductively developed subcategories of information sources were addressed in the studies. The most frequently reported sources of information were the Internet (n = 22) [5, 9, 10, 12, 23,24,25,26,27, 29, 31,32,33,34, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] and healthcare professionals (n = 17) [5, 9, 10, 12, 24, 26, 27, 29,30,31,32,33, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43]. Slightly fewer studies mentioned ‘relatives and friends’ (n = 10) [9, 10, 12, 26, 29, 31, 33, 36, 40, 43], ‘brochures and magazines’ (n = 7) [9, 12, 26, 29, 31, 36, 40], ‘books’ (n = 6) [9, 12, 29, 31, 33, 40] and ‘broadcast media’ (n = 6) [5, 12, 26, 29, 36, 43] as a source of information. Social networks were identified as information sources in six studies [25, 30, 36,37,38, 40], diabetes groups in three [12, 31, 42] and other patients [12, 26] in two studies. One study addressed several information sources [44]. However, these were described as “traditional” or “novel” sources, for example, without further specification of the terms [44].

Regarding the content of information, people with DM searched for ‘diet’ (n = 8) [5, 12, 22, 23, 32, 34, 36, 43], ‘complications’ (n = 8) [5, 12, 23, 24, 32, 34, 36, 43], ‘exercise’ (n = 8) [5, 12, 22, 23, 32, 34, 37, 43] and ‘medication and pharmacological interactions’ (n = 6) [12, 23, 32, 34, 36, 43]. Fewer studies investigated the information needs of pregnant women with DM (n = 3) [23, 34, 39].

Associated variables

Associated variables regarding the information-seeking behaviour of people with DM are presented in Table 4 in their respective categories.

Seven main categories associated with information-seeking behaviour were identified in the selected studies. Four categories were in line with Wilson’s model, namely ‘demographic’ (n = 10) [5, 10, 24, 27, 28, 33, 36, 38, 41, 42], ‘personal and role-related/interpersonal’ (n = 3) [27, 34, 44], ‘environmental’ (n = 1) [28], and ‘source characteristics’ (n = 4) [29, 30, 33, 35]. Variables of the category ‘psychological’ as defined in Wilson’s model were not addressed in the selected studies. Three further categories were ‘socioeconomic’ (n = 11) [5, 12, 24, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34, 36, 41], ‘duration of diabetes’ (n = 9) [5, 9, 12, 29,30,31, 36, 41, 44] and ‘lifestyle’ (n = 2) [22, 41].

Variables of the category ‘demographic’ associated with preferred information sources were identified in 10 studies [5, 10, 24, 27, 28, 33, 36, 38, 41, 42]. One study showed an association between female gender and older age, and reduced information-seeking behaviour [5]. Furthermore, studies showed that younger participants used the Internet more often to find health information [5, 24, 36, 38, 41] than the older population [27]. Only a few of the older participants used the Internet to seek health information [27]. Kalantzi et al. identified that younger participants preferred information about exercise, hypoglycaemia and dietary issues [5].

Variables of the category ‘personal, role-related and interpersonal’ were identified in three studies [27, 34, 44]. Childbearing women with T1DM preferred information about pregnancy and DM [34]. There appears to be a correlation between family and searching the Internet for health information [27]. Having a family history of DM is associated with a higher average of information-seeking behaviour scores, e.g. of interpersonal relationships [44].

Variables of the category ‘environmental’ were addressed in one study [28]. It was pointed out that cultural aspects such as a preference for herbal medicine or religious and spiritual beliefs could lead to an avoidance of healthcare professionals [28].

‘Source characteristics’ were also addressed [5, 29, 30, 33, 35]. The quality of information and its sources appears to be an associated variable. For example, Meyfroidt et al. point out that participants trusted information obtained from healthcare professionals most, due to their experience [29]. However, less trust is placed in advertisements, for example [29]. Milewski and Chen demonstrate that information that often addressed patients with recently diagnosed DM, especially in flyers and brochures, did not meet individual information needs [30]. Furthermore, this study showed that lower-quality information could lead to less-active seeking [30]. Another study showed that unorganised information appears to act as a barrier for younger people with diabetes [5].

Variables of the category ‘socioeconomic’ containing the variables education and income were identified in 11 studies [5, 12, 24, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34, 36, 41]. A higher level of education is associated with active information seeking and with more complex styles of information-seeking behaviour [28, 31]. Additionally, eight studies show that there is a correlation between educational background and preference for specific information sources [5, 24, 29, 33, 34, 36, 41]. A higher level of education seems to be associated with Internet use [24, 29, 34, 36, 41], while participants with a lower educational background appear to prefer verbal communication [24]. A higher income seems to be associated with the use of more complex styles of information-seeking behaviour, while participants with a lower income displayed more simple styles of information-seeking behaviour [31]. Similarly, two studies showed an association between socioeconomic variables and a preference for specific information sources [5, 41]. Kalantzi et al. show that a higher income is associated with a preference for the Internet as an information source, while a lower income is associated with a preference for personal contact (e.g. physicians) as the main source of information [5]. One study identified that a specific content of information is associated with a higher income and education level [5]. Participants with a higher level of education expressed greater interest in information about complications, hypoglycaemia and exercise. Similarly, participants with a higher income preferred information about complications and exercise [5].

Variables of the category ‘duration of DM’ were found in nine studies [5, 9, 12, 29,30,31, 36, 41, 44]. Five of them showed a correlation between the type of information-seeking behaviour and the duration of DM [5, 12, 29,30,31]. Two studies showed that participants start with active information seeking at the beginning of their disease, while a longer duration led to less-active seeking [5, 30]. Milewski and Chen assume that some participants seem to misjudge their disease as being stable and stop adapting once they have basic knowledge [30]. A correlation between duration of DM and preferred information sources was found in five studies [5, 9, 29, 36, 41], e.g. that the Internet was used as a fast alternative at an earlier stage, while health professionals were consulted in all phases of the disease [9, 29]. One study pointed out that participants in the first year of diagnosis preferred to search for baseline information, but after having DM for three or more years, they started to display more complex information-seeking behaviour [31].

Regarding the category ‘lifestyle’, Enwald et al. show that there is an association between the variables BMI and fitness classification, and the content of information [22]. Fitness classification was represented on a 7-point Likert scale with a range from ‘very poor’ to ‘excellent’ [45]. Participants with a lower fitness classification and a higher BMI showed a greater interest in seeking information about nutrition and exercise than those with better scores [22]. Lui et al. identified that participants with a higher BMI seem to search more often the Internet as a source of information [41].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to analyse existing knowledge about information-seeking behaviour of people with DM. Wilson’s model proved to be suitable during the systematic review analysis. Overall, there were few studies with high heterogeneity regarding the research question, design, methods and participants.

Types of information-seeking behaviour

Passive attention was described in patients with diabetes in some studies, in the sense that information was a by-product of everyday activities such as watching television or reading the newspaper [9]. The consequence of this passive role is that information does not always meet individual information needs [29,30,31]. Similar observations have not been made in people with cancer. However, a study with people with breast cancer indicated that healthcare professionals should pay attention to passive information seeking because the information obtained can influence healthcare decisions [46].

Some studies described more active information-seeking behaviour in which the Internet is used as an information source [9, 29]. Particularly, people with a higher level of education and higher income demonstrated a more active and complex type of information seeking [28, 31]. Moreover, a general shift from passive to more active seeking was recognised in one of our identified studies [5]. A similar observation was made in people with cancer [47]. It is therefore likely, then, that health professionals are dealing with more-informed patients [48, 49].

Information sources

The Internet appears to be a preferred source of information, including special information [9, 23,24,25, 27, 29, 32, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43], especially for younger patients and those with a higher level of education [5, 24, 36, 38, 41]. Some participants even noted that they prefer more official websites, such as the guidelines of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, to their doctor’s opinion [37]. However, people with DM largely wish to have Internet information verified by their general practitioner or other healthcare professionals such as dieticians and medical specialists [9, 23, 29, 39], and they ranked professionals as an information source highly [5, 24, 36]. Furthermore, patients with other chronic diseases such as cancer ranked healthcare professionals as their preferred source of information, whereas the media, including the Internet, was ranked in the middle [46, 47, 49]. Healthcare professionals such as diabetes educators ought to support people with DM to identify qualitative information and help them to improve their health literacy skills according to their individual needs [50].

Content of information

The studies showed that people with diabetes have a need to search for information about diabetes treatment [5, 12, 13, 22,23,24, 32, 34, 36, 37, 43]. However, it remains unclear, if information meets their information needs. It can be assumed that the information available does not meet individual information needs [29, 30] or that additional information is needed in where the disease has progressed [12, 28]. Also, a systematic review showed that people with cancer can have a deficit of information regarding ‘treatment options’ and ‘side effects of treatment’ [47].

Associated variables

Individual characteristics (e.g. demographics, socioeconomic status) and the duration of the disease appear to be associated with information-seeking behaviour [5, 10, 12, 24, 27,28,29, 31, 38, 41, 42, 44]. Carlsson found similar results with people with cancer: there was a significant correlation between a higher level of education and an active type of seeking behaviour, and younger participants used the Internet to find health information more often than older participants [51]. Interestingly, patients who predominantly obtain information from the Internet tend to make more independent health decisions or determine whether they need professional support. The Internet is also used where people are dissatisfied with the information provided by health professionals [48]. The progression of the disease is related to seeking behaviour, e.g. a reason for active search [12, 36], and for contacting a doctor [28]. Other studies, for example those including people with end-of-life diabetes, found that there is a correlation between individual information needs, especially those of informal caregivers, and emotional aspects, with the trajectory of the disease [52].

Implications

Our findings indicate that demographics and the socioeconomic status of people with DM are relevant in information management. It transpires that young people with DM require help from professionals in verifying Internet-based information, and perhaps additional information, while more detailed information ought to be provided to older patients and patients with a lower level of education, preferably verbally [24]. Furthermore, health professionals appear to be confronted with a shift from a more passive to a more active patient who is influenced by information from the Internet [9, 23, 25, 27, 29, 32, 48]. Perhaps, a more comprehensive way of exchanging information is needed to help patients to identify reliable information on the Internet by presenting suitable databases and preparing them to deal with several types of information.

Information provision could consider the stage of the disease [28, 36, 52], and informal caregivers could be involved where the disease is in a progressed stage. Research is needed to investigate individual strategies and needs in information-seeking behaviour over the course of the disease, giving consideration to demographics, socioeconomic status and the type of seeking. The heterogeneity of the studies’ populations indicates that further research is needed for each type of diabetes, also with regard to cultural aspects in information-seeking behaviour. The results of the critical appraisal also indicate that there is a need for well-designed studies with a higher level of internal and external validity.

Limitations

The inclusion criteria were handled rigorously, resulting in the inclusion of a small number of studies. A selection bias can be assumed because of the language and database restrictions. Studies published up to June 2015 were searched. In September 2016 and in June 2017, a forward citation tracking was performed in Google Scholar to find current relevant studies by searching studies that cited already-identified core publications [14]. We also performed an update of two of our core databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL) and identified several new publications. However, it cannot be completely ruled out that some publications were missed after June 2015.

Conclusion

There are a low number of studies analysing information-seeking behaviour, with a high heterogeneity regarding the research question, design, methods and participants. Both passive and active seeking seem to be performed by the patients; however, there may be a shift towards more active information-seeking behaviour. There is an association between information-seeking behaviour and demographics, socioeconomic and environmental aspects, source characteristics, and individual needs, including variations due to the progression of the disease. Younger people with higher levels of education and higher incomes especially prefer to search for information on the Internet, which is, however, not a substitute for information provided by healthcare professionals. More well-performed studies are needed to re-evaluate existing models of patient information-seeking behaviour.

Change history

04 December 2017

During the production process for this article [1] some errors were introduced into Table 2. The correct version of Table 2 can be found below; the original article [1] has also been updated with the correct version of Table 2. BMC apologises to the authors and to readers for this error.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- DARE:

-

Database of Abstract of Reviews of Effects

- DDZ:

-

German Diabetes Center

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DZD:

-

German Center for Diabetes Research

- EED:

-

The NHS Economic Evaluation Database

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica Database

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes

- HbA1C%:

-

Percentage of glycated haemoglobin

- Iddm:

-

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- Isb:

-

Information-seeking behaviour

- ISI:

-

Institute of Science Index

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- Niddm:

-

Noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PsycINFO:

-

Psychological Information Database

- T1DM:

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002.

Icks A, Haastert B, Gandjour A, Chernyak N, Rathmann W, Giani G, et al. Costs of dialysis—a regional population-based analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010; doi:10.1093/ndt/gfp672.

Icks A, Scheer M, Morbach S, Genz J, Haastert B, Giani G, et al. Time-dependent impact of diabetes on mortality in patients after major lower extremity amputation: survival in a population-based 5-year cohort in Germany. Diabetes Care. 2011; doi:10.2337/dc10-2341.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 2015:2015. http://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 13 Jun 2017

Kalantzi S, Kostagiolas P, Kechagias G, Niakas D, Makrilakis K. Information seeking behavior of patients with diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study in an outpatient clinic of a university-affiliated hospital in Athens. Greece BMC Res Notes. 2015; doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1005-3.

Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159–71.

Wilson TD. Human information behavior. Information Science. 2000:49–55.

Wilson TD. Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Information Processing & Management. 1997; doi:10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9.

Longo DR, Schubert SL, Wright BA, LeMaster J, Williams CD, Clore JN. Health information seeking, receipt, and use in diabetes self-management. Ann Fam Med. 2010; doi:10.1370/afm.1115.

Hyman I, Patychuk D, Zaidi Q, Kljujic D, Shakya YB, Rummens JA, et al. Self-management, health service use and information seeking for diabetes care among recent immigrants in Toronto. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2012; doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.08.267.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

St. Jean B. Information behavior of people diagnosed with a chronic serious health condition: a longitudinal study [dissertation]. 2012.

St. Jean B. Devising and implementing a card-sorting technique for a longitudinal investigation of the information behavior of people with type 2 diabetes. Library & Information Science Research. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2013.10.002.

Bakkalbasi N, Bauer K, Glover J, Wang L. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed Digit Libr. 2006; doi:10.1186/1742-5581-3-7.

Ryan R. Cochrane consumers and communication review group: data synthesis and analysis. 2013. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Analysis.pdf. Accessed 19 Mar 2017.

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J. "Best fit" framework synthesis: Refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-37.

Finfgeld-Connett D. Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qual Res. 2014; doi:10.1177/1468794113481790.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publ; 2009.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health. 2012.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, Seller R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009.

Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009.

Enwald HPK, Niemelä RM, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Leppäluoto J, Jämsä T, Herzig K-H, et al. Human information behaviour and physiological measurements as a basis to tailor health information. An explorative study in a physical activity intervention among prediabetic individuals in northern Finland. Health Inf Libr J. 2012; doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00968.x.

Nordfeldt S, Johansson C, Carlsson E, Hammersjö J-A. Use of the Internet to search for information in type 1 diabetes children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Technol Health Care. 2005;13:67–74.

Robertson JL, Akhtar S, Petrie, JR, Brown FJ, Jones GC, Perry CG, Paterson KR. How do people with diabetes access information? Pract Diab Int. 2005; doi:10.1002/pdi.818.

Shaw RJ, Johnson CM. Health information seeking and social media use on the Internet among people with diabetes. Online J Public Health Inform. 2011; doi:10.5210/ojphi.v3i1.3561.

Yamamoto Y, Nishigaki M, Kato N, Hayashi M, Shiba T, Mori Y, et al. Knowledge and demand for information about islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Transp Secur. 2011; doi:10.1155/2011/136298.

Connolly KK, Crosby ME. Examining e-health literacy and the digital divide in an underserved population in Hawaii. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73:44–8.

Moonaghi HK, Areshtanab HN, Joibari L, Bostanabad MA, McDonald H. Struggling towards diagnosis: experiences of Iranian diabetes. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014; doi:10.5812/ircmj.16547.

Meyfroidt S, Aeyels D, van Audenhove C, Verlinde C, Peers J, Panella M, Vanhaecht K. How do patients with uncontrolled diabetes in the Brussels-capital region seek and use information sources for their diet? Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013; doi:10.1017/S1463423612000205.

Milewski J, Chen Y. Barriers of obtaining health information among diabetes patients. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160:18–22.

Newton P, Asimakopoulou K, Scambler S. Information seeking and use amongst people living with type 2 diabetes: an information continuum. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2012; doi:10.1080/14635240.2012.665581.

Wilson V. Patient use of the Internet for diabetes information. Nurs Times. 2013;109:18–20.

Morgan AJ, Trauth EM. Socio-economic influences on health information searching in the USA: the case of diabetes. Info Technology & People. 2013; doi:10.1108/ITP-09-2012-0098.

Sparud-Lundin C, Ranerup A, Berg M. Internet use, needs and expectations of web-based information and communication in childbearing women with type 1 diabetes. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011; doi:10.1186/1472-6947-11-49.

St. Jean B. Factors motivating, demotivating, or impeding information seeking and use by people with type 2 diabetes: a call to work toward preventing, identifying, and addressing incognizance. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2016; doi:10.1002/asi.23652.

Jamal A, Khan SA, AlHumud A, Al-Duhyyim A, Alrashed M, Bin Shabr F, et al. Association of online health information-seeking behavior and self-care activities among type 2 diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia. J Med Internet Res. 2015; doi:10.2196/jmir.4312.

Fergie G, Hilton S, Hunt K. Young adults’ experiences of seeking online information about diabetes and mental health in the age of social media. Health Expect. 2016; doi:10.1111/hex.12430.

Giménez-Pérez G, Recasens A, Simó O, Aguas T, Suárez A, Vila M, Castells I. Use of communication technologies by people with type 1 diabetes in the social networking era. A chance for improvement. Prim Care Diabetes. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2015.09.002.

Kilgour C, Bogossian FE, Callaway L, Gallois C. Postnatal gestational diabetes mellitus follow-up: Australian women’s experiences. Women Birth. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2015.06.004.

Low LL, Tong SF, Low WY. Social influences of help-seeking behaviour among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016; doi:10.1177/1010539515596807.

Lui C-W, Col JR, Donald M, Dower J, Boyle FM. Health and social correlates of Internet use for diabetes information: findings from Australia’s living with diabetes study. Aust J Prim Health. 2015; doi:10.1071/PY14021.

Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Sources of information on gestational diabetes mellitus, satisfaction with diagnostic process and information provision. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016; doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1067-9.

Weymann N, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Information and decision support needs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Health Informatics J. 2016; doi:10.1177/1460458214534090.

Zare-Farashbandi F, Lalazaryan A, Rahimi A, Hasssanzadeh A. The effect of contextual factors on health information-seeking behavior of Isfahan diabetic patients. J Hosp Librariansh. 2016; doi:10.1080/15323269.2016.1118266.

Shvartz E, Reibold RC. Aerobic fitness norms for males and females aged 6 to 75 years: a review. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990;61:3–11.

Longo DR, Ge B, Radina ME, Greiner A, Williams CD, Longo GS, et al. Understanding breast-cancer patients’ perceptions: health information-seeking behaviour and passive information receipt. Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 2013; doi:10.1179/cih.2009.2.2.184.

Rutten LJF, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006.

McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006; doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006.

Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Kreps GL, Menon U, McCance K, Parsons SK, Mooney KH. Cancer survivors information seeking behaviors: a comparison of survivors who do and do not seek information about cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007; doi:10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.015.

Schillinger D. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002; doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.475.

Carlsson M. Cancer patients seeking information from sources outside the health care system. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:453–7.

Dikkers MF, Dunning T, Savage S. Information needs of family carers of people with diabetes at the end of life: a literature review. J Palliat Med. 2013; doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0265.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Consent of publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Funding

The German Diabetes Study was initiated and is financed by the DDZ (German Diabetes Center), which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (Berlin, Germany) and the Ministry of Innovation, Science, Research and Technology of the state North Rhine-Westphalia (Düsseldorf, Germany). The present analysis was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.) and by the Research Commission of the Faculty of Medicine of the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf [9772577].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Sigrid Droste is deceased. This paper is dedicated to his memory.

- Sigrid Droste

The original version of this article was revised due to errors in table 2.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0646-9.

Contributions

SK, TS, SG and AI contributed to the concept, design, and drafting of the review. SK, SD and SG participated in the development of the systematic search strategies. TS, AP and SK participated in the title-abstract and full-text selection. SK, AI, TS and SH contributed to the writing and editing of the review and to the critical revision of the important intellectual content of the manuscript. The authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Prof. Silke Kuske, Ph.D., is affiliated with the Institute for Health Services Research and Health Economics, Centre for Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

Tim Schiereck, Sandra Grobosch, Andrea Paduch and Sigrid Droste (deceased) are affiliated with the Institute for Health Services Research and Health Economics, Centre for Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

Sarah Halbach is affiliated with the Institute for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University of Bonn.

Prof. Dr. Andrea Icks, MBA, is the Head of the Institute for Health Services Research and Health Economics, Center for Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, and is also the Head of the Institute Paul Langerhans Group for Health Services Research and Health Economics, German Diabetes Center, Leibniz Center, at the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (professorship unlimited). She is a member of the German Center for Diabetes Research, Neuherberg, Germany.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised due to errors in table 2.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0646-9.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

The PRISMA statement (2009). (DOC 84 kb)

Additional file 2:

Update search strategy (MEDLINE, CINAHL) and search strategy (Ia and Ib). (DOC 343 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuske, S., Schiereck, T., Grobosch, S. et al. Diabetes-related information-seeking behaviour: a systematic review. Syst Rev 6, 212 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0602-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0602-8