Abstract

Introduction

Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) has emerged as a challenge to global tuberculosis (TB) control and remains a major public health concern in many countries. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an increasingly recognized comorbidity that can both accelerate TB disease and complicate its treatment. The aim of this study is to summarize available evidence on the association of DM and MDR-TB among TB patients and to provide a pooled estimate of risks.

Methods

All studies published in English before October 2016 will be searched using comprehensive search strings through PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and WHO Global Health Library databases which have reported the association of DM and MDR-TB in adults with TB (age > =15). Two authors will independently collect detailed information using structured data abstraction form. The quality of studies will be checked using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort and case-control studies and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality tool for cross-sectional studies. Heterogeneity between included studies will be assessed using the I2 statistic. We will check potential publication bias by visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test statistic. We will use the random effects model to compute a pooled estimate.

Discussion

Increases in the burden of non-communicable diseases and aging populations are changing the importance of different risk factors for TB, and the profile of comorbidities and clinical challenges for people with TB. Although classic risk factors and comorbidities such as overcrowding, under-nutrition, silicosis, and HIV infection are crucial to address, chronic conditions like diabetes are important factors that impair host defenses against TB. Thus, undertaking integrated multifaceted approach is remarkably necessary for reducing the burden of DM and successful TB treatment outcome.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016045692.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) has emerged as a challenge to global tuberculosis (TB) control and remains a major public health concern in many countries. It is an infectious disease caused by strains of mycobacterium TB that are resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin [1]. Drug-resistant TB has been reported since the early days of the introduction of anti-TB chemotherapy [2].

In the year 2014, an estimated 3.3% of new cases and 20% of previously treated TB cases have MDR-TB [3]. The eastern European and central Asian countries have the highest levels of MDR-TB. For example, estimated new TB cases with MDR-TB were 34% in Belarus and 26% in both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan [3]. Similarly, the estimated re-treatment TB cases with MDR-TB were as high as 69% in Belarus and 58% in Kazakhstan [3]. Globally in 2014, 190,000 deaths occurred due to MDR-TB. It is also estimated that 99,000 cases of MDR-TB emerge every year, of which 62,000 were among notified cases of TB in 2014 [3].

The emergence of multi-drug resistance across the world poses a global threat as the treatment is difficult, expensive, and a major health care cost burden to developing countries [4]. Most cases of MDR-TB are arising from a mixture of physician error, inadequate and incomplete treatment, and patient non-compliance during treatment of susceptible TB [5, 6]. The international community has responded with financial and scientific support, leading to new rapid diagnostics, new drugs, and regimens in advanced clinical development [7].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an increasingly recognized comorbidity that can both accelerate TB disease and complicate TB treatment. The prevalence of DM among TB patients around the world varies according to different regions that range from 12 to 44% and tended to increase in the past decade [8]. It increases the risk of TB disease, complicates TB treatment, and increases the risk of a poor TB outcome [9, 10]. Among MDR-TB patients, DM is a relatively common comorbidity [11]. In addition to the well-established contribution of DM to enhanced TB risk, there is growing evidence from observational studies that this comorbidity is associated with delays in mycobacterium TB clearance during treatment, treatment failures, death, relapse and re-infection [12]. However, whether DM presents any additional risk for the development or acquisition of MDR-TB remains controversial [13–15]. Three case-control studies comparing DM/TB and non-diabetic TB patients from Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey showed no significant association between DM and the risk of MDR-TB [16–18]. Similarly, cross-sectional studies in Iran, Turkey, and Taiwan have reported no association between DM and MDR-TB [19–21]. On the other hand, many studies have found 2.1 to 8.8 times increased the risk of MDR-TB among diabetic TB patients [22–26]. In addition, observational studies from Israel, Georgia, and Mexico have also shown patients with DM had a higher risk of developing MDR-TB [27–29].

Similarly, none of the systematic reviews and meta-analysis conducted so far [10, 11, 22, 30–36] has addressed DM associated risk of developing MDR-TB. Thus, further meta-analysis and synthesis of the available evidence is needed now. This systematic review and meta-analysis will be done to identify gaps on whether there is a risk of MDR-TB associated with DM and provide the necessary evidence to design (inter)national policy guidelines for the management of MDR-TB. Hence, the current study aims to summarize available evidence on the association of DM and MDR-TB and to provide a pooled estimate on the risk of DM for developing MDR-TB.

Methods

Protocol and registration

Our systematic review has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016045692; registration number CRD42016045692). This protocol is written in accordance with recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement [37] and the PRISMA-P checklist has been completed (see Additional file 1). Results will be reported based on the PRISMA statement guideline [38, 39].

Eligibility criteria

We will include all observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort, survey, and surveillance reports) which have reported the association of DM and MDR-TB in adults with TB (age > =15). All studies published in English before October 2016 will be reviewed as well.

Data source and search strategy

PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database(EMBASE), Web of Science, and WHO Global Health Library databases will be searched for all publications. We will also search bibliographies of identified articles and gray literature. In addition, authors will be contacted and requested for additional information in case of missing data. In consultation with an experienced medical information specialist, comprehensive search strategy has been developed (see Additional file 2).

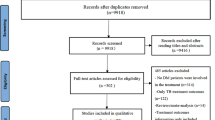

Study selection

Articles will be screened and selected for full-text review if they met the following selection criteria: (1) they provided or permitted the computation of an effect estimate of DM on the development of MDR-TB among TB patients. (2) They included TB patients (all type) and defined MDR-TB based on standard protocols. (3) They defined DM as any of the following: baseline diagnosis by self-report, medical records, laboratory test, or treatment with oral hypoglycemic medications or insulin. We will exclude studies for any of the following reasons: citations without abstracts; anonymous reports; duplicate studies; case reports or studies which did not compare MDR-TB among people with DM to people without DM; systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Also, studies in which people with DM received different anti-TB treatment regimens than people without DM and studies that either did not provide effect estimates in odds ratios, rate ratios, hazard ratios, or relative risks or did not allow for the computation of these values will be excluded. Two reviewers will screen and check full-text studies for inclusion independently. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer will determine the eligibility and approve the final list of retained studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Structured data abstraction form will be constructed and pre-tested. For every study that met our eligibility criteria, two investigators (BS and TD) independently will extract the title, name of authors, year of publication, country, study design, study population, sample size, data collection procedure, diagnosis of DM, and MDR-TB, adjustment for potential confounders, effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals and proportion of TB-diabetic patients who developed MDR. Search results will be compiled using citation management software (RefWorks 2.0; ProQuest LLC, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://www.refworks.com). The same authors (BS and TD) will check the quality of studies independently using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [40] for cohort and case-control studies and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ARHQ) [41] tool for cross-sectional studies. Disagreement will be resolved by consensus. In case of persistent disagreement a third reviewer will be consulted.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3.5 (Cochrane Informatics and Knowledge Management Department) for Windows [42] will be used for analysis. Heterogeneity between included studies will be assessed using the I2 statistic described by Higgins et al. with I2 from 75 to 100% suggesting considerable heterogeneity [43].We will check potential publication bias by visual inspection of the funnel plot. Besides, Egger’s regression test will be used to statistically check the asymmetry of the funnel plot [44]. Publication bias will be assumed P value less than 0.10.

Original studies will be described using study characteristics summary table and forest plot. A meta-analysis, to compute a pooled estimate, will be performed if variability among studies is low. However, if the pooling of data is not feasible due to heterogeneity, we will descriptively report the results of each study. Odds ratio will be used as a measure of overall association between DM and MDR-TB. We will meta-analyze estimates with similar sets of confounds. Presuming the variation of the true effect of DM on MDR-TB for different populations, we will use the random effects model and weighting method [45]. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression will be performed for types of DM and types of TB.

Discussion

Increases in the burden of non-communicable diseases and aging populations are changing the importance of different risk factors for TB. Although classic risk factors and comorbidities such as overcrowding, undernutrition, silicosis, and HIV infection are crucial to address, chronic conditions like diabetes are important factors that impair host defenses against TB [46].

The association of diabetes and TB was confirmed by Root since 1934 [47]. So far, many types of research and reviews have confirmed this finding and suggest that the overall risk of TB in persons with DM is two to three times higher than in the general population [10, 46, 48]. DM in this association may still contribute substantially to the burden of TB and negatively affect the treatment outcome. Chronic hyperglycemia at least to some extent may alter the treatment outcome and prognosis of TB [49]. Several studies have been conducted to assess the association between MDR-TB and DM in different regions of the world [13, 15–17, 22]. However, these studies did not provide consistent evidence on whether DM has an increased risk for MDR-TB. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aim to provide a pooled estimate on the risk of DM for developing MDR-TB.

Clinicians and researchers should generate the necessary evidence for improvements to patient services and policies on combined TB and diabetes [50]. Our review will clarify the existing controversies on whether DM puts the higher risk for MDR-TB. Hence, the results of this review will be helpful to remove confusions for policy-makers, clinicians, and patients and it might be helpful to undertake integrated approach for reducing the burden of DM on successful TB treatment outcome.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MDR-TB:

-

Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. World Health Organization multidrug and extensively drug-resistant TB (M/XDR-TB): 2010 global report on surveillance and response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Espinal MA. The global situation of MDR-TB. Tuberculosis. 2003;83(1):44–51.

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Nations JA, Lazarus AA, Walsh TE. Drug-resistant tuberculosis. Dis Mon. 2006;52(11-12):435–40.

Ormerod LP. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB): epidemiology, prevention and treatment. Br Med Bull. 2005;73-74:17–24.

Jain A, Dixit P. Multidrug resistant to extensively drug resistant tuberculosis: what is next? J Biosci. 2008;33(4):605–16.

Kurz SG, Furin JJ, Bark CM. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: challenges and progress. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30(2):509–22.

Ko P, Lin S, Tu S, Hsieh M, Su S, Hsu S, et al. High diabetes mellitus prevalence with increasing trend among newly-diagnosed tuberculosis patients in an Asian population: a nationwide population-based study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2016;10(2):148–55.

Alkabab YM, Al-Abdely HM, Heysell SK. Diabetes-related tuberculosis in the Middle East: an urgent need for regional research. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;40:64–70.

Jeon CY, Murray MB. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of active tuberculosis: a systematic review of 13 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e152.

Kang YA, Kim SY, Jo KW, Kim HJ, Park SK, Kim TH, et al. Impact of diabetes on treatment outcomes and long-term survival in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Respiration. 2013;86(6):472–8.

Restrepo BI, Schlesinger LS. Impact of diabetes on the natural history of tuberculosis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(2):191–9.

Kameda K, Kawabata S, Masuda N. Follow-up study of short course chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis complicated with diabetes mellitus. Kekkaku. 1990;65(12):791–803.

Park S, Shin J, Kim J, Park I, Choi B, Choi J, et al. The effect of diabetic control status on the clinical features of pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(7):1305–10.

Chang J, Dou H, Yen C, Wu Y, Huang R, Lin H, et al. Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the clinical severity and treatment outcome in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a potential role in the emergence of multidrug-resistance. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110(6):372–81.

Singla R, Khan N, Al-Sharif N, Al-Sayegh M, Shaikh M, Osman M. Influence of diabetes on manifestations and treatment outcome of pulmonary TB patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(1):74–9.

Tatar D, Senol G, Alptekin S, Karakurum C, Aydin M, Coskunol I. Tuberculosis in diabetics: features in an endemic area. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009;62(6):423–7.

Baghaei P, Tabarsi P, Abrishami Z, Mirsaeidi M, Faghani YA, Mansouri SD, et al. Comparison of pulmonary TB patients with and without diabetes mellitus type II. Tanaffos. 2010;9(2):13–20.

Tanrikulu AC, Hosoglu S, Ozekinci T, Abakay A, Gurkan F. Risk factors for drug resistant tuberculosis in southeast Turkey. Trop Dr. 2008;38(2):91–3.

Chiang CY, Bai KJ, Lin HH, Chien ST, Lee JJ, Enarson DA, et al. The influence of diabetes, glycemic control, and diabetes-related comorbidities on pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121698.

Baghaei P, Tabarsi P, Chitsaz E, Novin A, Alipanah N, Kazempour M, et al. Risk factors associated with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. TANAFFOS-J Respir Dis Thorac Surg Intensive Care Tuberc. 2009;8(3):17–21.

Baghaei P, Marjani M, Javanmard P, Tabarsi P, Masjedi MR. Diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis facts and controversies. J Diabet Metabol Disord. 2013;12(1):1.

Pérez-Navarro LM, Fuentes-Domínguez FJ, Zenteno-Cuevas R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and its influence in the development of multidrug resistance tuberculosis in patients from southeastern Mexico. J Diabet Complications. 2015;29(1):77–82.

Rifat M, Milton AH, Hall J, Oldmeadow C, Islam MA, Husain A, et al. Development of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Bangladesh: a case-control study on risk factors. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105214.

Suarez-Garcia I, Rodriguez-Blanco A, Vidal-Perez J, Garcia-Viejo M, Jaras-Hernandez M, Lopez O, et al. Risk factors for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a tuberculosis unit in Madrid, Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28(4):325–30.

Bashar M, Alcabes P, Rom WN, Condos R. Increased incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in diabetic patients on the Bellevue Chest Service, 1987 to 1997. CHEST J. 2001;120(5):1514–9.

Bendayan D, Hendler A, Polansky V, Weinberger M. Outcome of hospitalized MDR-TB patients: Israel 2000–2005. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(3):375–9.

Kikvidze M, Mikiashvili L. Impact of diabetes mellitus on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment outcomes in Georgia-Cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42 Suppl 57:2826.

Gómez-Gómez A, Magaña-Aquino M, López-Meza S, Aranda-Álvarez M, Díaz-Ornelas DE, Hernández-Segura MG, et al. Diabetes and other risk factors for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in a Mexican population with pulmonary tuberculosis: case control study. Arch Med Res. 2015;46(2):142–8.

Mi F, Jiang G, Du J, Li L, Yue W, Harries AD, et al. Is resistance to anti-tuberculosis drugs associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus? A register review in Beijing, China. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24022.

Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shah NS, Andrews JR, Friedland GH, Moll AP, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(3):153–61.

Johnston JC, Shahidi NC, Sadatsafavi M, Fitzgerald JM. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6914.

Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, Hart JE, Kapur A, Lönnroth K, et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):1.

Jacobson KR, Tierney DB, Jeon CY, Mitnick CD, Murray MB. Treatment outcomes among patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(1):6–14.

Faustini A, Hall AJ, Perucci CA. Risk factors for multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a systematic review. Thorax. 2006;61(2):158–63.

Ettehad D, Schaaf HS, Seddon JA, Cooke GS, Ford N. Treatment outcomes for children with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(6):449–56.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217.

Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Bastian H, Chalmers I, et al. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001419.

Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta‐analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2–10.

Nordic Cochrane Centre The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan)[Computer program] Version 53. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Higgins J, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Lönnroth K, Roglic G, Harries AD. Improving tuberculosis prevention and care through addressing the global diabetes epidemic: from evidence to policy and practice. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):730–9.

Root HF. The association of diabetes and tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1934;210(3):127–47.

Stevenson CR, Critchley JA, Forouhi NG, Roglic G, Williams BG, Dye C, et al. Diabetes and the risk of tuberculosis: a neglected threat to public health? Chronic Illn. 2007;3(3):228–45.

Skowroński M, Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz D, Barinow-Wojewódzki A. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus–an underappreciated association. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10(5):1019–27.

Riza AL, Pearson F, Ugarte-Gil C, Alisjahbana B, van de Vijver S, Panduru NM, et al. Clinical management of concurrent diabetes and tuberculosis and the implications for patient services. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):740–53.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Sjoukje van der Werf (medical information specialist) in this study for her invaluable support in the development of search strings.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

BS and TD conceived and designed the study. BS and TD developed the search strings. BS, TD, MM, and JB wrote the manuscript. All of these authors provided critical comments for revision and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol. (DOC 82 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search strings used and number of identified literature per database. (DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tegegne, B.S., Habtewold, T.D., Mengesha, M.M. et al. Association between diabetes mellitus and multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 6, 6 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0407-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0407-9