Abstract

Background

The welfare state is potentially an important macro-level determinant of health that also moderates the extent, and impact, of socio-economic inequalities in exposure to the social determinants of health. The welfare state has three main policy domains: health care, social policy (e.g. social transfers and education) and public health policy. This is the protocol for an umbrella review to examine the latter; its aim is to assess how European welfare states influence the social determinants of health inequalities institutionally through public health policies.

Methods/design

A systematic review methodology will be used to identify systematic reviews from high-income countries (including additional EU-28 members) that describe the health and health equity effects of upstream public health interventions. Interventions will focus on primary and secondary prevention policies including fiscal measures, regulation, education, preventative treatment and screening across ten public health domains (tobacco; alcohol; food and nutrition; reproductive health services; the control of infectious diseases; screening; mental health; road traffic injuries; air, land and water pollution; and workplace regulations). Twenty databases will be searched using a pre-determined search strategy to evaluate population-level public health interventions.

Discussion

Understanding the impact of specific public health policy interventions will help to establish causality in terms of the effects of welfare states on population health and health inequalities. The review will document contextual information on how population-level public health interventions are organised, implemented and delivered. This information can be used to identify effective interventions that could be implemented to reduce health inequalities between and within European countries.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016025283

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Socio-economic inequalities are associated with unequal exposure to social, economic and environmental risk factors, which in turn contribute to health inequalities. People with higher income, employment and educational opportunities have lower mortality and morbidity [1]. Social inequalities in health are widespread, for example in Europe where an estimated 80 million people are living in relative poverty [2]. Important European differences in health outcomes have been attributed to variations in how the welfare state is administered [3, 4]. The welfare state is therefore potentially an important macro-level determinant of health which also moderates the extent, and impact, of socio-economic inequalities in exposure to the social determinants of health. The welfare state has three main policy domains: health care, social policy (e.g. social transfers and education) and public health policy. This planned umbrella review examines the latter; its aim is to assess how European welfare states influence the social determinants of health inequalities institutionally through public health policies. Understanding the impact of specific public health policy interventions will help to establish causality in terms of the effects of welfare states on population health. This review will therefore help identify effective interventions that could be implemented to reduce health inequalities between and within European countries.

Many commentators have sought to define what is meant by public health. The World Health Organization [5] emphasises how public health refers to ‘all organized measures (whether public or private) to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among the population as a whole’. The system of administering public health to populations could be the private or voluntary sector, but in European welfare states, it is most usually instigated by governments—centrally, regionally or locally. Welfare states may impact the health of citizens either indirectly through influencing the social determinants of health (e.g. through changes to social policy such as education, social security and housing) or directly through health care systems or policies aimed at promoting public health specifically [6, 7]. The proposed umbrella review will examine the latter aspect of European welfare states.

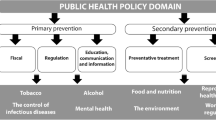

Public health policies can operate on a number of different levels, which affects population health and health inequalities. Following Mackenbach and McKee [8], public health policies may influence primary prevention (which aims to avoid the occurrence of a disease by reducing exposure to health risks) or secondary prevention (which aims to avoid the development of a disease to a symptomatic stage by diagnosing and treating the disease before it causes significant morbidity of the disease) (p. 195). Public health interventions may occur at multiple levels. Downstream interventions involve individual-level behavioural approaches for prevention or disease management, and their success depends on whether some sections of the population are more likely to take up or successfully engage with certain initiatives compared to others [9]. Upstream interventions involve state or institutional control, regulating the supply of a particular substance or activity, promoting a method of preventative health behaviour or improving the wider environment. These population-level interventions will be the focus for the proposed umbrella review, as they are likely to reduce socio-economic inequalities in health and have the greatest influence on overall population health within a territory [10–13].

The nature of public health interventions means their influence percolates into many aspects of how we behave, live and work. For the purposes of this review, we categorise these interventions into fiscal policy, regulation, education, preventative treatment and screening. It is also helpful to consider the broad areas by which local and national governments may intervene and regulate. An example of the public health domain groupings (and intervention types) we propose can be found in Table 1. These groups are based on the ten areas of public health policy that Mackenbach and McKee [7, 14] identify as contributing to major population health gains: tobacco; alcohol; food and nutrition; reproductive health services; the control of infectious diseases; screening; mental health; road traffic injuries; air, land and water pollution; and workplace regulations. Whilst acknowledging that this list may not be exhaustive, its inclusion highlights the broad areas that our final report will focus on. Furthermore, distinguishing public health policies from other welfare state policy domains such as social policy may not be clear-cut (the division is based on practicality as a parallel review on social and health care policy is also underway). Public health policies influence almost all aspects of society, but the focus here centres on policies directly influencing health (e.g. the control of infectious diseases), or those indirectly regulating other areas of government regulation policy which have clear and direct pathways to (poor) health (e.g. workplace regulations).

Whilst there are many excellent reviews which focus on specific public health areas (e.g. [15, 16]), to our knowledge, there is no truly comprehensive umbrella systematic review which has sought to evaluate the full suite of population-level public health policies available to governments. Lorenc et al. [10] undertook a rapid review searching only one database (Medline) and identified 12 reviews meeting their inclusion criteria. Bambra et al. [17] conducted a much more complete review which focused on both social and public health policies. However, their searching only spanned the period 2000–2007, and at that time, the authors concluded that the systematic review evidence base was unclear to determine the effects of interventions on health inequalities. Nor did these previous reviews focus on the potential importance of different welfare state context. In recent years, there has been an effort to promote health equity by encouraging authors of systematic reviews to document health inequalities amongst disadvantaged groups through reporting guidelines such as ‘PRISMA-E 2012’ and ‘PROGRESS-PLUS’ [18–20]. It is therefore timely to update these umbrella reviews and comprehensively document population-level public health interventions designed to improve health and reduce health inequalities.

Methods

Our systematic review was designed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [21]. A PRISMA-P checklist is available as an Additional file 1 to this protocol. This protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016025283).

Research question

What are the effects of population-level public health policies on health and health inequalities in European welfare states?

Study design

A systematic review methodology will be used to locate and evaluate published systematic review-level evidence on the effects of public health policy regulation on health and inequalities in health (‘umbrella review’) [17, 22, 23]. Umbrella reviews are an established method of locating, appraising and synthesising systematic reviews [24]. Umbrella reviews are therefore able to present the overarching findings of such systematic reviews (usually considered to be the highest level of evidence) and can also extract data from the best quality studies within them [17]. In this way, they represent an effective way of rapidly reviewing a broad evidence base. An umbrella review methodology is an increasingly used technique in public health and medical research but is seldom used in the evaluation of institutional policies or the social determinants of health [24, 25]. Although umbrella reviews have been published on particular aspects of public health interventions (e.g. [13, 15, 17, 22]), no comprehensive umbrella review has been reported detailing the full suite of public health policies which governments may use to influence public health and reduce health inequalities.

Inclusion criteria

Following standard evidence synthesis approaches [18], the inclusion criteria for the review are determined a priori in terms of PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Setting; [26]).

-

Population: Children and adults (all ages) in any high-income country (defined as Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD) members) and additional EU-28 members not OECD members.Footnote 1 The population is kept purposively broad to allow the widest range of literature to be identified.

-

Intervention: Upstream, population-level and public health policies defined as primary and secondary interventions. The inclusion criteria are purposely broad to allow for a range of different public health interventions to be located. Table 1 gives an indication of the type of interventions which this review may highlight. The domains listed and the specific intervention types are however illustrative of the variety of policy areas and interventions which public health spans and should not be considered exhaustive.

-

Comparison: We will include systematic reviews that include studies with and without controls. Acceptable controls include randomised or matched designs.

-

Outcomes: Health and health inequality outcomes. Primary outcome measures include (but are not limited to) morbidity, health behaviours, mortality, accidents and injuries. Secondary outcomes relate to health inequalities in terms of gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status (defined as individual income, wealth, education, employment or occupational status, benefit receipt; as well as area-level economic indicators). When available, cost-effectiveness data will also be collected.

-

Setting: Only systematic reviews will be included in the analysis.

Following the methods of previous umbrella reviews [17, 22], publications will need to meet the two mandatory criteria of Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): (i) that there is a defined review question (with definition of at least two of the participants, interventions, outcomes or study designs) and (ii) that the search strategy included at least one named database, in conjunction with either reference checking, hand searching, citation searching or contact with authors in the field. When two reviews are identified with the same research question, only the most recent umbrella review will be synthesised as part of this study. A rigorous and inclusive literature search for existing systematic reviews will be conducted, incorporating a range of study designs (following [27]), including randomised and nonrandomised controlled trials, randomised and nonrandomised cluster trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies (with and/or without control groups), prospective repeat cross-sectional studies (with and/or without control groups) and interrupted time series (with and/or without control groups).

Search strategy

Twenty databases will be searched from their start until March 2016 (host sites given in parentheses): Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Social Science Citation Index (Web of Science), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; ProQuest), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS; ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Social Services Abstracts (ProQuest), PROSPERO (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York), Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews (The Campbell Library), Cochrane Library (includes Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, DARE, Health Technology Assessment Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database; Wiley), Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER; EPPI-Centre), Social Care Online (SCIE) and Health Systems Evidence. All searches will be tailored to the specific host site; an example search strategy is shown for Medline in Additional file 2. To complement these searches, citation follow-up from the bibliographies and reference lists of all included articles will be conducted. No language or publication date restrictions will be included. Searches will be limited to peer-reviewed publications only. Authors will be contacted to obtain any relevant information that is missing. If reviews do not have sufficient data, they will be excluded from further analysis.

The proposed search terms used in the search strategy are shown in Additional file 2. After careful consideration, and some initial searches, inequality terms were not included in the final search strategy. It was decided to screen the articles after the initial search to maximise ‘hits’ using the PROGRESS-Plus acronym recommended by the Cochrane/Campbell Health Equity Group [18, 19]. The framework includes socio-economic factors that may impact health equity including Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socio-economic status and Social capital [28]. The additional ‘Plus’ captures further variables of age, disability and sexual orientation that may indicate a disadvantage [18]. Due to the diverse nature of interventions this review will synthesise, a discrete list of health outcomes has not been generated either, but will be reviewed post screening.

Screening, data extraction and quality appraisal

The initial screening of titles and abstracts using EndNote will be conducted by one reviewer (KT), with a random sample of at least 10 % (in keeping with previous successful reviews, e.g. [27]) checked by a second reviewer (AT or CM). Full-text copies of potentially relevant articles will then be examined for inclusion by two reviewers independently (KT and CM or AT). Any discrepancies will be resolved through discussion between the two reviewers, and, if consensus is not reached, with the project lead (CB). Furthermore, inter-rater reliability will be assessed using the kappa statistic.

Data will be extracted using standard data extraction forms based on previous reviews [17]. The following data will be extracted: the intervention type reviewed; the study population in the review (and in the included studies); any age/gender/location, etc. restrictions in the review; the number of relevant studies in the review (total); number of databases searched (total); whether grey literature was searched or citation follow-up conducted; any time/language/country restrictions in the review; study design of studies included in the review (e.g. randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled prospective cohort, repeat cross sections); the method of synthesis (meta-analysis or narrative); any details on implementation of interventions contained within the review; and the main findings both at a population level and in terms of socio-economic inequalities in health.

Quality will be assessed using a checklist adapted from DARE, which has been used successfully in previous umbrella reviews [22]. Articles will be categorised as low (met 0–3 criteria), medium (4–5) or high (6–7) quality, with one point attributed for each of the questions answered ‘yes’ on the methodological checklist in Table 2.

Synthesis

If meta-analysis has been undertaken, the effect size will be used. In cases of narrative summaries where no summary effect sizes are provided, an exploration of patterns in the data will be accompanied by a discussion of similarities and differences between the findings of different studies. A detailed commentary on the major methodological problems or biases in the review will also be included, alongside an assessment of completeness and applicability [29]. We will also incorporate an assessment of the quality of included systematic reviews in our interpretation of findings—something which has been lacking in previous umbrella reviews [25]. We will synthesise the health effects at a population level and also at subgroup level with regard to health inequalities (e.g. gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status). An assessment of the strength of evidence will be made using GRADE [30].

Pilot search strategy

A pilot search strategy has been conducted in Medline (via Ovid) and is shown in Table 3. At each stage, the type of study (pilot 1), intervention (pilot 2) and outcomes (health, pilot 3 and SES, pilot 4) are added. Three key papers were used as examples to see if the different searches located them. Pilot search 1 used a search strategy based primarily on the Health Information Research Unit of McMaster University [31] and also the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) filter for systematic reviews [32]. Additionally, specific reference to umbrella reviews was included to ensure existing umbrella systematic reviews were highlighted and their bibliographic literature added where necessary. This identified over 355,412 records. Next, population-level intervention terms were added (pilot 2). When combined with the systematic review terminology previously searched, the number of hits dropped dramatically to 8,821. Pilot 3 includes examples of outcomes and reduces the number of hits only slightly to 8,550. Adding inequality terminology reduced the number of hits further to ca. 1,700 (pilot 4). Although adding outcome terms (pilots 3 and 4) decreased the number of hits to one fifth compared to just using the type of study and population-level terms (pilot 2), it was felt that these outcome terms should not be included in the final search strategy. Instead, the search strategy advocated in pilot 2 would be used and screening for outcome terms would occur after the initial searches have been conducted. This was in part due to the variety of interventions (and therefore outcomes) which this public health review might highlight. The search strategy will be adapted for each of the specific databases; an example for Medline (Ovid) is shown in Additional file 2.

Discussion

This umbrella review will provide evidence of macro, population-level public health interventions which affect health and reduce health inequalities amongst European welfare states. Understanding the impact of specific public health policy interventions will help to establish causality in terms of the effects of welfare states on population health and health inequalities and, most importantly, identify effective interventions that could be implemented to reduce health inequalities across European countries. The umbrella review will consider public health strategies across ten different domains of public health, and, as such, it will also serve as a mapping exercise of the types of interventions that have been systematically reviewed, thereby highlighting any gaps in the systematic review evidence base. The review will also seek to establish (where reported) how such public health interventions are organised, implemented and delivered. Context is increasingly recognised as an important factor in the success of public health interventions [33] and has begun to be taken into account in systematic reviews. However, the assessment of implementation has not featured strongly in previous umbrella reviews. We will therefore develop and refine existing methodological tools and apply them to umbrella reviews [33, 34]. The review also adds to the literature that conceptualises public health regulation as one of the three tiers of the welfare state—alongside health care access/provision and social policy [14].

Notes

The World Bank classifies as high-income countries those countries with GNI per capita income of $12,736 or more for the current 2016 fiscal year. Further details can be found at http://data.worldbank.org/income-level/OEC. The list of OECD countries includes Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Israel, Japan, Korea Republic, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK and the USA. Additional EU-28 countries not included in the previous list were also added (including Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Romania).

Abbreviations

- DARE:

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

- EU-28:

-

European Union member countries

- PICOS:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Setting

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROGRESS-Plus:

-

Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socio-economic status and Social capital-Plus

- PROSPERO:

-

international prospective register of systematic reviews

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

References

Graham H. Unequal lives: health and socioeconomic inequalities. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2007.

European Commission. Joint report on social protection and social inclusion. Brussels: European Commission; 2007.

Bambra C. Health inequalities and welfare state regimes: theoretical insights on a public health ‘puzzle’. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2011;65(9):740–5. doi:10.1136/jech.2011.136333.

Bergqvist K, Yngwe MA, Lundberg O. Understanding the role of welfare state characteristics for health and inequalities—an analytical review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1234

World Health Organization. Public health. 2015. http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story076/en/. Accessed 16th November 2015.

Bambra C, Fox D, Scott-Samuel A. Towards a politics of health. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(2):187–93. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah608.

MacKenbach JP, McKee M. Social-democratic government and health policy in Europe: a quantitative analysis. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(3):389–413. doi:10.2190/HS.43.3.b.

Mackenbach JP, McKee M. A comparative analysis of health policy performance in 43 European countries. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(2):195–201. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks192.

Macintyre S. Modernising the NHS: prevention and reduction of health inequalities. BMJ. 2000;320:1399–400.

Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2013;67(2):190–3. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201257.

White M, Adams J, Heywood P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? In: Babones SJ, editor. Social Inequality and Public Health. Bristol: Policy Press; 2009. p. 65-83

Macintyre S. Inequalities in Scotland: what are they and what can we do about them? Glasgow: MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit; 2007.

Main C, Thomas S, Ogilvie D, Stirk L, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, et al. Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking: placing an equity lens on existing systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:6. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-178.

Mackenbach JP, McKee M, editors. Successes and failures of health policy in Europe: four decades of divergent trends and converging challenges. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2013.

Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(E2). doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110.

Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden AJ, Wright K, Whitehead M, Petticrew M. Working for health? Evidence from systematic reviews on the effects on health and health inequalities of organisational changes to the psychosocial work environment. Prev Med. 2009;48(5):454–61. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.018.

Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, Wright K, Whitehead M, Petticrew M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2010;64(4):284–91. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.082743.

Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Lorenc T. Reflections on developing and using PROGRESS-Plus. Equity Update. 2008;2:1–3.

Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Kristjansson E, Oliver S, Ueffing E, Welch V. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: subgroup analysis and equity. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2012;66(1):95–8. doi:10.1136/jech.2010.121095.

Welch V, Petticrew M, Petkovic J, Moher D, Waters E, White H et al. Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:68-89. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.001.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Cairns J, Warren J, Garthwaite K, Greig G, Bambra C. Go slow: an umbrella review of the effects of 20 mph zones and limits on health and health inequalities. J Public Health. 2015;37(3):515–20.

Bambra C. Social inequalities in health: the Nordic welfare state in a comparative context. In: Kvist J, Fritzell J, Hvinden B, Kangas O, editors. Changing social equality: the Nordic Welfare Model in the 21st century. Bristol: Policy Press; 2012. p. 143-63.

Becker L, Oxman A. Overviews of reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2008.

Bambra C, Gibson M. Case study of public health. In: Biondi-Zoccai G, editor. Umbrella reviews—evidence synthesis with overviews of reviews and meta-epidemiologic studies. Chem: Springer; 2016; p. 343-62.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008.

Bambra C, Hillier F, Moore H, Cairns-Nagi J-M, Summerbell C. Tackling inequalities in obesity: a protocol for a systematic review of the effectiveness of public health interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity among adults. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):27.

Evans T, Brown H. Road traffic crashes: operationalizing equity in the context of health sector reform. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10(1-2):11–2. doi:10.1076/icsp.10.1.11.14117.

Ryan R. Cochrane consumers and communication review group. Cochrane consumers and communication review group: data synthesis and analysis. 2013. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/. Accessed 29th February 2016.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schuenemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):380–2. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011.

McMaster University. Reviews: search filters for MEDLINE in Ovid syntax and the PubMed translation. Health Information Research Unit. 2016. http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/HIRU_Hedges_MEDLINE_Strategies.aspx. Accessed 1st March 2016.

Scottish Inter-collegiate Guide-lines Network (SIGN). Search Filters. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh. 2015. http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html. Accessed 4th December 2015.

Egan M, Bambra C, Petticrew M, Whitehead M. Reviewing evidence on complex social interventions: appraising implementation in systematic reviews of the health effects of organisational-level workplace interventions. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2009;63(1):4–11. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.071233.

Bambra C, Hillier F, Cairns JM, Kasim A, Moore H, Summerbell C. How effective are interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity among children and adults? Two systematic reviews. Public Health Research. 2015;3(1). doi:10.3310/phr03010.

Oldroyd J, Burns C, Lucas P, Haikerwal A, Waters E. The effectiveness of nutrition interventions on dietary outcomes by relative social disadvantage: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2008;62(7):573–9. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.066357.

Bambra C, Garthwaite K, Hunter D. All things being equal: does it matter for equity how you organize and pay for health care? A review of the international evidence. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(3):457–77. doi:10.2190/HS.44.3.c.

Footman K, Garthwaite K, Bambra C, McKee M. Quality check: does it matter for quality how you organize and pay for health care? A review of the international evidence. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(3):479–505. doi:10.2190/HS.44.3.d.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of the HiNEWS project—Health Inequalities in European Welfare States—funded by the NORFACE (New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Cooperation in Europe) Welfare State Futures programme (grant reference: 462-14-110). For more details on NORFACE, see www.norface.net. We thank Heather Robb for her advice in developing the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KT led the drafting and revising of the manuscript with the input from CB. AT, CM and TH contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses Protocols) 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol. (DOC 83 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search Strategy—Medline (Ovid). (DOC 39 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomson, K., Bambra, C., McNamara, C. et al. The effects of public health policies on population health and health inequalities in European welfare states: protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev 5, 57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0235-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0235-3