Abstract

Background

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common, life-long paediatric disability. Taking care of a child with CP often results in caregiver burden/strain in the long run. As caregivers play an essential role in the rehabilitation of these children, it is therefore important to routinely screen for health outcomes in informal caregivers. Consequently, a plethora of caregiver burden outcome measures have been developed; however, there is a dearth of evidence of the most psychometrically sound tools. Therefore, the broad objective of this systematic review is to evaluate the psychometrical properties and clinical utility of tools used to measure caregiver burden in caregivers of children with CP.

Methods/design

This is a systematic review for the evaluation of the psychometric properties of caregiver burden outcome tools. Two independent and blinded reviewers will search articles on PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsychINFO and Africa-Wide Google Scholar. Information will be analysed using predefined criteria. Thereafter, three independent reviewers will then screen the retrieved articles. The methodological quality of studies on the development and validation of the identified tools will be evaluated using the four point COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist. Finally, the psychometric properties of the tools which were developed and validated from methodological sound studies will then be analysed using predefined criteria.

Discussion

The proposed systematic review will give an extensive review of the psychometrical properties of tools used to measure caregiver burden in caregivers of children with CP. We hope to identify tools that can be used to accurately screen for caregiver burden both in clinical setting and for research purposes.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42015028026.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Provision of care for a child with a long-term health condition is often associated with negative health outcomes in caregivers, for instance, depression, stress, anxiety and low self-efficacy were reported in caregivers [1–6]. Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common paediatric disability causing long-term functional limitations [7, 8]. Children with CP most often present with multiple impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions [9, 10]. More so, due to its diverse and complex presentation, CP is envisaged as the prototype paediatric disability [7, 8]. As such, most children require lifetime extensive assistance in functional day to day activities [10–12]. The level of required assistance depends on the severity of impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions [13]. Taking care of a child is part of normal parenthood; however, the excessive demands associated with taking care of a child with a disability may lead to increased burden/strain [5, 14]. Consequently, long-term caregiving for a child with CP may negatively affect the well-being of caregivers [4, 12, 15].

Caregiver burden has been defined as “strain or load borne by a person who cares for a family member with a disability” [16]. Caregiver burden is multifactorial complex, subjective and dynamic as envisaged in different conceptual models which have been developed to explain this construct [16–19]. The conceptual model by Raina et al. (2004) is one of the mostly cited and applied caregiver burden conceptual frameworks [19]. It postulates that caregiver burden is an interaction between the caregivers’ background, contextual factors, child characteristics, intrapsychic factors and coping factors [19]. For instance, presence of behavioural problems in children with CP, caregivers’ socio-economic status, availability of social support and caregivers’ self-efficacy all affect the overall perception of the burden of care [19]. Although usage of diverse semantics in describing caregiver burden makes it difficult to come up with a universally conceptualized definition and model, it is clear that long-term caregiving may lead to physical, psychological, emotional, social and financial strain [16–18].

With the advent of patient-centred and family-centred approaches to clinical care, the need to evaluate services from the perspective of patients, specifically the perceived impact of care on patients’ well-being, becomes more inherent [20]. More so, it is essential to evaluate the health outcomes in caregivers as they are an invaluable resource in the rehabilitation of children with long-term disabilities [5, 6]. For instance, the caregiver acts as the provider, decision maker, companion, custodian and advocator for a child with a disability [21]. Thus, routine assessment/screening of caregiver burden is of paramount importance for optimal functional outcomes of children with disabilities.

Given the well-documented effects of caregiving on the health of caregivers, it is important to routinely screen for caregivers burden/strain [5]. This is only attainable through the use of psychometrically sound outcome measures [14]. According to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines, an outcome measure has to be valid, reliable and responsive in order for it to adequately capture the construct it is purposed to measure [22]. Over the past few decades, there has been an exponential increase in the number of outcome measures to evaluate burden of care [14]. However, some of them are generic in nature and their utility in measuring burden of care in caregivers of children with disabilities may be questionable [14, 23, 24]. Further, there is a paucity of systematic evidence of the psychometric rigour of tools that have been used to measure the caregivers’ burden while taking care of a child with a disability.

Therefore, the broad objective of this systematic review is to evaluate the psychometrical properties of tools that have been utilized to measure caregiver burden in caregivers of children with CP. The specific objectives are to:

-

1.

Identify tools used to measure perceived caregiver burden in caregivers of children with CP

-

2.

Evaluate the psychometric properties of the identified outcome measurement tools

-

3.

To evaluate the clinical utility of the identified outcome measurement tools

Methods

Protocol/ registration

In conducting this review, we will utilize the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) guidelines [25]. The protocol has been registered on PROSPERO database (Ref: CRD42015028026).

Eligibility criteria

In selecting the studies, we will apply the following criterion:

Study designs/interventions

We will give precedence to articles on the development and validation of tools for measuring caregiver burden in caregivers of children with CP and/or other physical disabilities such as spinal bifida hydrocephalus among others. In as much as CP is considered to be a prototype paediatric disability [7, 8], we hypothesize that the burden of caring may be equivalent, regardless of the causative condition .Therefore, we will also include other disabilities such as hydrocephalus, spinal bifida among others. We will also consider studies that evaluated caregiver burden/strain in informal caregivers of children with CP and/or other disabilities or interventional studies with caregiver burden as an outcome measurement. We will exclude systematic reviews, qualitative studies, case studies and editorial letters. To capture as much information as possible, all quantitative study designs will be considered.

Participants

We will include studies examining the perceived burden of care in informal caregivers (18 years or older) of children with disabilities in the age range 0–12 years. We are cognisant of the changes in the dynamics of caregiving along the developmental trajectory. For instance, the dynamics of caregiving for a teenager with a disability may be different from providing care for a child in the age range 0–12 years [26]. Additionally, in the present review, an informal caregiver is defined as someone who takes the primary responsibility for caregiving a child with CP and are not formally educated nor remunerated for assuming the caregiver role.

Language

We will be selecting articles published in English language only as we do not have the financial resources for the translation of articles published in other languages. Further, when we performed our preliminary searches, we did not come across tools that were developed in languages other than English.

Information sources

We will search the following databases from their inception up to September 2015: PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, PsychINFO and Africa-Wide information. To ensure literature saturation, where only abstracts are available online, we will first try to contact the authors to see if a full text is available. If, after consulting the authors, only an abstract is available, we will exclude this abstract from our review.

We will also review grey literature, i.e. we will use the Google Scholar search engine to search potential databases such as university databases conference proceedings among others for articles. For completeness, the reference lists of identified articles will also be manually searched.

Search strategy

Outlined in Table 1 below is an example of how we will search for the articles in CINAHL database.

As an illustration, we will input the following key words to search articles in the CINAHL database: (“Caregiver” OR “care*” OR “mother”) AND (“burden” OR “strain” OR “stress” OR “distress”) AND (“outcome” OR “tool” OR “scale”) AND( “valid*” OR “reliability” AND “dev*”) AND (“CP” OR “cerebral palsy” OR “disabilit*” OR “long term health condition”) AND (“child” OR “paediatr*” AND “development” OR “construction”).

Data management

The articles will be imported into RevMan (version 5.3) data management software. The electronic searches will also be saved on users’ PubMed Scopus and EBSCOhost accounts. We will also print the summaries of all the searches to enhance the data capturing of the search records. The principal investigator will create a Google Drive folder which will act as repository of all the articles, which will be made available to all authors.

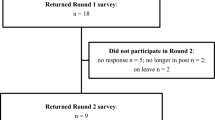

Data collection process

The principal author (JD) will search the databases and extract the titles and abstracts for further investigation. Thereafter, two researchers (NM and MC) will independently retrieve the full manuscripts of articles deemed relevant. Two other independent reviewers (LC and TM) will blindly screen the retrieved articles using a standardized data collection form. Information to be extracted will include the research setting and design, study sample, demographics of the participants, mode of administration, number of items, cost, total possible score and the year in which the tool was developed. In the event of a disagreement, a third reviewer (JJ) will make the final decision.

Outcomes and prioritization

For this review caregiver burden/strain will be the primary outcome measure.

Risk of bias individual studies

The four-point COSMIN checklist [22, 27] will be used to assess the methodological quality of the reviewed studies. This is essential to prevent the risk of selecting and evaluating tools which were developed using designs with poor methodological rigour [22]. The COSMIN checklist rates the rigour of the reliability, validity, responsiveness, hypothesis testing, interpretability and generalizability of studies on the development and use of health-related patient-reported outcomes [22, 27]. Items are rated on a four-point Likert scale, i.e. “excellent”, “good”, “fair” and “poor”. Where details are not published, the authors of the article will be contacted to achieve the most truthful rating of the assessment tool and to decrease bias in the analysis.

Psychometric properties and data extraction

The psychometrical properties will be evaluated using the checklist as outlined by Terwee et al. [28] (See Table 2). Each psychometric property can be rated as positive negative or questionable. An ideal tool should possess positive ratings [28].

Best evidence synthesis

Where a tool has validated in several studies, we will combine the findings to come with the best evidence for that particular tool. We will use a previously established criterion for synthesizing evidence by the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group [29] as outlined in Table 3.

Discussion

We hope to identify the most psychometrically sound, caregiver burden outcome measures. This is important given a plethora of tools which have been developed to measure this multidimensional construct. This is especially important for clinical use as there is a great need to routinely screen of caregivers at risk or who are exhibiting signs of strain/distress. Identification and use of caregiver burden outcomes with rigorous psychometrical properties will also enhance the credibility, methodological rigour and overall external validity and comparability of interventions for improving caregiver burden.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments

- CP:

-

cerebral palsy

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol

References

Pousada M, Guillamón N, Hernández-Encuentra E, Muñoz E, Redolar D, Boixadós M, et al. Impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy on the quality of life of parents: a systematic review of the literature. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2013;25:545–77.

Kaya K, Unsal-delialioglu S, Ordu-gokkaya NK, Ozisler Z, Ergun N, Ozel S, et al. Musculo-skeletal pain, quality of life and depression in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1666–72.

Palsili S, Anksiyete A, Üniversitesi H, Fakültesi T, Fiziksel T, Nöroloji P, et al. Anxiety and depression levels in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Turkish J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;53(November):2006–8.

Byrne MB, Hurley DA, Daly L, Cunningham CG. Health status of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:696–703.

Dambi JM, Jelsma J, Mlambo T. Caring for a child with cerebral palsy: the experience of Zimbabwean mothers. African J Disabil. 2015;4:1–10.

Dambi JM, Jelsma J. The impact of hospital-based and community based models of cerebral palsy rehabilitation: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:1–10.

Gagliardi C, Maghini C, Germiniasi C, Stefanoni G, Molteni F, Burt DM, et al. The effect of frequency of cerebral palsy treatment: a matched-pair pilot study. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39:335–40.

Berker AN, Yalçin MS. Cerebral palsy: orthopedic aspects and rehabilitation. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1209–25. ix.

Martin B, Murray G, Peter R, Alan L, Nigel P. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005.pdf. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:571–6.

Odding E, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:183–91.

Aisen ML, Kerkovich D, Mast J, Mulroy S, Wren TA, Kay RM, et al. Cerebral palsy: clinical care and neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:844–52.

Vargus-Adams J. Parent stress and children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:777.

Dambi JM, Chivambo G, Chiwaridzo M, Matare T- Health-Related Quality of Life of Caregivers of Childrenwith Cerebral Palsy and Minor Health Problems in Zimbabwe: A Descriptive, Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2015;5:11.

Wijesinghe CJ, Fonseka P, Hewage CG. The development and validation of an instrument to assess caregiver burden in cerebral palsy: caregiver difficulties scale. Ceylon Med J. 2013;58(October):162–7.

Raina P, Donnell MO, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J,Stephen D, Russell D, Swinton M, Zhu B, Wood E, Walter SD. The health and well-being of caregivers ofchildren with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics; 2005;115:6.

Oh H, Lee EO. Caregiver burden and social support among mothers raising children with developmental disabilities in South Korea. Int J Disabil, Dev Educ. 2009;56:149–67.

Reid CE, Moss S, Hyman G. Caregiver reciprocity: the effect of reciprocity, carer self-esteem and motivation on the experience of caregiver burden. Aust J Psychol. 2005;57:186–96.

Murphy NA, Christian B, Caplin DA, Young PC. The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: caregiver perspectives. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33:180–7.

Raina P, Donnell MO, Schwellnus H, Rosenbaum P, King G, Brehaut J, et al. Caregiving process and caregiver burden: conceptual models to guide research and practice. BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:1–13.

Cieza A, Stucki G. Content comparison of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instruments based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1225–37.

Dambi JM, Makotore FG, Kaseke F. The Impact of Caregiving a Child with Cancer: A Cross Sectional Study of Experiences of Zimbabwean Caregivers. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:230. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000230.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Gibbons E, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. Inter-rater agreement and reliability of the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments) checklist. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10(82).

Graessel E, Berth H, Lichte T, Grau H. Subjective caregiver burden: validity of the 10-item short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:23.

Erel S, Yakut Y, Uygur F. Turkish version of impact on family scale: a study of reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:1–7.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Carona C, Crespo C, Canavarro MC. Similarities amid the difference: caregiving burden and adaptation outcomes in dyads of parents and their children with and without cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:882–93.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22.

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42.

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1929–41.

Acknowledgements

The systematic review is part of the principal investigators’ PhD Physiotherapy dissertation work. The University Of Cape Town (UCT) has provided a scholarship to the principal investigator (JD) to pay for tuition fees through the JW Jagger Centenary Gift Schol scholarship. There was no external funding for the present protocol; however, the University Of Cape Town Faculty Of Health Sciences Library provided technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JD was primarily responsible for protocol writing. JD, JJ, LC and TM were involved in the conceptualization of the study and editing of the protocol. JD will be responsible for searching the literature and data management. Both MC and NDM will be responsible for article screening and quality assurance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dambi, J.M., Jelsma, J., Mlambo, T. et al. An evaluation of psychometric properties of caregiver burden outcome measures used in caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 5, 42 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0219-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0219-3