Abstract

In two-hop relay-aided cellular networks, both half-duplex (HD) and full-duplex (FD) transmission have been extensively studied. FD transmission can achieve twice throughput of HD transmission, but suffers from strong self-interference (SI), which may not be perfectly cancelled. In this paper, a hybrid HD/FD transmission scheme in a relay-aided cellular network is proposed, which not only utilizes the throughput advantage of FD but also weakens the negative effect of SI. The key idea is that a relay station (RS) switches between the HD and the FD modes based on the received signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR). If the information rate of the base station (BS)-to-RS link is lower than a preset threshold, the RSs adopt the FD mode to guarantee the throughput; otherwise, the RSs adopt the HD mode to reduce the negative effect of SI. As FD transmission consumes more power than HD transmission, we try to maximize the system energy efficiency under the system spectral efficiency constraint and the transmit power constraints. It is difficult to solve this optimization problem directly, so the alternate optimization method is adopted to solve it, i.e., optimizing the transmit power of the BS and the transmit power of RSs in turn. Simulation results show that under perfect SI cancellation, the hybrid scheme can achieve higher energy efficiency than the HD mode by taking the throughput advantage of FD; while under poor SI cancellation, the hybrid scheme can greatly weaken the negative effect of SI and achieve higher energy efficiency than the FD mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Modern cellular networks need to provide ubiquitous coverage and high data rates with low infrastructure deployment cost [1]. The incorporation of two-hop fixed relays, which are connected to base-stations via wireless backhaul, provides a convenient solution toward such a goal. In particular, cooperative relaying in wireless networks is an attractive solution for extending base station coverage and filling coverage gaps that affect user equipment’s performance in the strongly shadowed urban environment. There are two main types of relaying schemes, namely half-duplex (HD) relaying and full-duplex (FD) relaying.

In literature, a large number of works have been done on HD relaying which focused on spectral efficiency [2], channel capacity [3], outage probability [4], etc., as it enables a low-complexity relay design. Nevertheless, HD relaying systems require additional resources (frequency bands or time slots) to transmit data in a multi-hop manner which results in a loss of spectral efficiency.

On the contrary, although FD relaying suffers from inherent self-interference (SI) which was considered impractical in the past, it has regained the attention of both industry [5, 6] and academia [7–9]. Recent research shows that FD relaying is feasible by using interference cancellation techniques and transmit/receive antenna isolation [10–13]. Some works on FD relaying in cellular systems have been done. For example, in [14], the authors focused on designing FD cellular networks with co-channel femtocells. Because wireless virtualization can provide more flexibility, diversity, and other benefits in wireless network design, the authors in [15] introduced the idea of wireless virtualization into FD cellular networks. Because the FD relaying can achieve higher spectral efficiency than HD relaying, a new device-to-device (D2D) communication scheme was proposed that allows D2D links to underlay cellular downlink by assigning D2D transmitters as FD relays to assist cellular downlink transmission [16]. Although these excellent works have been done for FD relaying in cellular networks, the energy efficiency aspect of FD relay systems did not receive much attention.

With the exponential growth of data traffic, energy consumption of wireless networks has been rapidly increasing, and energy-efficient design of wireless networks has become the focus of both academia and industry [17, 18]. However, the existing works on energy efficiency analysis of relay systems mainly focused on the HD mode, which cannot be directly applied in FD relay systems because of SI. The spectral-energy efficiency tradeoff in FD two-way relay networks has been studied [19], in which an optimization problem was formulated to maximize the energy efficiency under the spectral efficiency requirement and the transmit power constraint. A shared FD relay deployment scenario, where a FD relay is deployed at the intersection of several adjacent cell sectors, was considered in [20]. Energy efficiency was also studied in FD massive multi-input multi-output (MIMO) systems [21, 22].

Some researchers also considered hybrid HD/FD transmission schemes, which combine the advantages of both HD and FD. In [23], an optimal transmission scheduling scheme for a hybrid HD/FD relaying system was proposed, which can attain higher spectral efficiency than the HD mode or FD mode. In [24], duplex mode selection and transmit power adaptation were integrated to maximize the spectral efficiency. In [25], the network interference from FD mode cells was characterized in a heterogeneous network operating in the FD or HD mode. In [26], a unified model was proposed to represent four hybrid relay modes and a joint relay mode selection and power allocation algorithm was developed.

Motivated by the above-mentioned works in FD relaying, a hybrid HD/FD transmission scheme in a relay-aided cellular network is studied in this paper. The system energy efficiency in the hybrid scheme is evaluated under the system spectral efficiency constraint and is compared with those of the HD and FD modes. This hybrid scheme not only utilizes the throughput advantage of FD but also weakens the negative effect of SI. The authors in [24] also studied hybrid HD/FD transmission and transmit power optimization. They considered a two-hop relay system with direct link, where the flexible switching can be done between HD and FD as well as between relaying and direct transmission. However, the switching between HD and FD is based on the end-to-end SINR, which requires global channel state information compared to the proposed hybrid scheme. Besides, they only considered maximizing the system spectral efficiency but ignored the system energy efficiency, which is very important for energy-efficient implementation of the hybrid scheme in the 5G era.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the relay-aided cellular network model and the downlink transmission for HD, FD, and hybrid modes. Then, the energy-efficient power allocation problem is formulated and solved in Section 3. Section 4 presents the simulation results. Finally, some concluding remarks are made in Section 5.

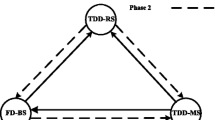

1.1 System model

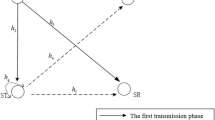

We consider a downlink, two-hop, relay-aided wireless cellular network as depicted in Fig. 1. We focus on a single cell where the base station (BS) is located at the center of the cell. The coverage radius of the cell is denoted by R. We consider the case where there is no direct link between the BS and the mobile users (MUs) due to shadowing, which may happen when the BS and the MUs are far away from each other. Moreover, coordinated multi-point transmission among the relay stations (RSs) is not considered. There is one BS, a set of K RSs, and a set of K MUs staying within the cell. The BS and the MUs are equipped with a single antenna while it is beneficial to equip the RSs with isolated receive and transmit antennas. Each MU connects with the BS through the RS and each RS is allowed to connect only one MU for simplicity. The decode-and-forward relaying protocol is adopted.

The network comprises three kinds of wireless links: feeder link (from the BS to the RS), access link (from the RS to the MU), and residual SI link (from a RS’s transmit antenna to its receive antenna). Their channel coefficients are denoted by H SR, H RM, and H L, respectively. Moreover, the channels H SR, H RM are assumed to experience Rayleigh block fading. We denote H SR, H RM ~ CN(0, d − ν), where v is the path-loss exponent and d is the distance between the respective transmitter and receiver. The transmit power of the BS and the kth RS are denoted by P B and \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{k}}} \), respectively. The unit-variance transmitted signal from the BS and the RS are denoted by X S and X R, respectively.

1.2 Downlink transmission

1.2.1 HD mode

In the HD mode, each transmission frame is divided into two stages. The downlink transmission can be split into two parts: feeder link and access link.

Signal transmission in feeder links

In the first stage, the BS transmits a signal to the associated RSs in a broadcast manner. The signals received at the RSs in the cell can be written as

where \( {H}_{{\mathrm{SR}}_k} \) is the channel coefficient from the BS to the kth RS and U k is an additive white Gaussian noise with zero mean and variance σ 2. The SINRs at the RSs can be calculated as

The information rate of the kth feeder link can be expressed as

where W is the cell bandwidth.

Signal transmission in access links

In the second stage, each RS forwards the decoded signal to its associated MU. It is assumed that the decoding is always successful. The received signals at the MUs in the cell can be written as

where \( {H}_{{\mathrm{RM}}_k} \) is the channel coefficient from the kth RS to its associated MU, U k is an additive white Gaussian noise with variance σ 2, and I k is the co-channel interference among the RSs. The SINRs at the MUs can be calculated as

The information rate of the kth access link can be expressed as

1.2.2 FD mode

The FD relaying allows simultaneous transmission and reception over the same frequency band. Thus, the communication quality is degraded by SI from a RS transmit antenna to its receive antenna. For the convenience of description, the downlink transmission is also split into two parts: feeder link and access link.

Signal transmission in feeder links

The BS transmits a signal to the associated RSs also in a broadcast manner. The signal received at a RS includes both SI and co-channel interference among the RSs. Therefore, after SI cancellation (by using antenna isolation, SI cancellation techniques, etc.), the signal received at the kth RS in the cell can be written as

where \( {H}_{{\mathrm{L}}_k}^{\hbox{'}}=\beta {\mathrm{H}}_{{\mathrm{L}}_k} \), \( {H}_{{\mathrm{L}}_k} \) is the SI channel coefficient from the transmit antenna to the receive antenna of the kth RS, β(0 ≤ β ≤ 1) is the interference cancellation factor at the RSs (obviously, β = 0 indicates that the SI is perfectly cancelled, but it is impossible in practical environments), \( G={\left|{H}_{{\mathrm{L}}_k}^{\hbox{'}}\right|}^2 \) is the SI channel gain, which is caused by imperfect cancellation of SI, and N k is the co-channel interference from the other RS transmissions. The SINRs at the kth RS can be calculated as

The information rate of the kth feeder link can be expressed as

From this expression, we find that a larger power of residual SI will result in a lower rate of the feeder link. That is to say, the residual SI couples the feeder link and the access link, which makes power allocation at RSs quite important and different from that of HD relay systems.

Signal transmission in access links

Each RS also forwards the decoded signal to its associated MU. It is assumed that the decoding is always successful. So the signals received at the kth MU in the cell can be written as

where \( {H}_{{\mathrm{RM}}_k} \) is the channel coefficient from the kth RS to its associated MU and I k is the co-channel interference among the RSs. The SINRs at the kth MU can be calculated as

The information rate of the kth access link can be expressed as

To guarantee the throughput, the information rate of the feeder link should be no lower than that of the access link [20], i.e., \( {R}_{{}_{\mathrm{Feeder}}}^k\ge {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^k \). Here, the information rate \( {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^k \) can be viewed as the effective service rate for each MU. From the above signal transmissions, the cell throughput can be expressed as

1.2.3 Hybrid mode

In the hybrid mode, a RS switches between the HD mode and the FD mode with a certain probability. For the ease of analysis, suppose now the kth RS is working on the HD mode. In the first stage, if \( {\mathrm{SINR}}_{1,k}^{\mathrm{HD}}\le {I}_{th} \), where I th is the preset SINR threshold that the access link requires, in order to improve the information rate of the access link, the kth RS will switch to the FD mode; otherwise, the kth RS will stay in the HD mode. So, the cell throughput can be expressed as

where \( x={e}^{-\frac{a}{P_B}},\ a=\frac{I_{th}.{\sigma}^2}{d^{\hbox{-} \nu }} \).

1.3 Power consumption model

The power consumption of the stations can be expressed as a linear form similar to [27, 28]:

where the coefficients a B and a R, respectively, account for power consumption that scales with the average radiated power, and the terms b B and b R model the static power consumed by signal processing, battery backup, and cooling. Therefore, if the RSs work on the FD mode, the total power consumption is written as

where P C = b B + Kb R is the static power consumed by signal processing, battery backup, and cooling. When the RSs work on the HD mode, the static power P C is the same as that in FD, but the average radiated power is half of that in FD. The total power consumption is written as

According to the total probability formula, if the RSs work on the hybrid mode, the total power consumption can be written as

The system spectral efficiency and system energy efficiency can be respectively defined as

2 Energy-efficient power allocation

The energy-efficient power allocation problem is formulated to maximize the system energy efficiency under the system spectral efficiency and the transmit power constraints, which is

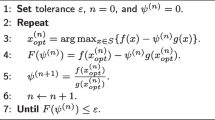

where \( \overline{\eta_{\mathrm{SE}}} \) is the minimum spectral efficiency requirement, \( {\displaystyle {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{B}}} \) and \( {\displaystyle {\overline{P}}_{{\displaystyle {\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{k}}}}} \) are the maximum allowed transmit powers of the BS and the RSs, respectively. Here for simplicity it is assumed that the transmit powers of the RSs are the same. According to the signal transmissions described above, the cell throughput only includes the effective service rate of the MUs, and the information rate of feeder links is not included. We further consider the information rate of feeder links as a constraint in the following, which guarantees that the information rate of a feeder link is no lower than that of a corresponding access link. The above optimization problem is not concave in P B and \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) jointly. To overcome this difficulty, we adopt the alternating optimization method (i.e., first fix the BS power and optimize the power of each RS; then fix the RS power and optimize the BS power) to maximize the system energy efficiency under the constraints below. This method can reach a near-optimal solution with affordable computational complexity, compared to other optimization methods.

2.1 Optimizing over P B for a fixed \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \)

Given a fixed \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \), our target is to seek the optimal transmit power P B to maximize the system energy efficiency while satisfying the above-mentioned constraints. Thus, the problem (P) can be rewritten as

Obviously, with a fixed \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \), η SE is a strictly decreasing function of P B. However, the objective function is a fractional function and it is hard to find the optimal solution. To overcome this issue, we apply the fractional programming technique [29] to transform the objective function to an integral expression. The optimal value \( {q}^{*}=\frac{\eta_{\mathrm{SE}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}}^{*},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}^{*}\right)}{P_{\mathrm{T}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}}^{*},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}^{*}\right)} \) can be achieved as long as \( {\eta}_{\mathrm{SE}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}}^{*},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}^{*}\right)-{q}^{*}{P}_{\mathrm{T}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}}^{*},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}^{*}\right)=0 \). Hence, we can conclude that the solution of sub-problem Eq. (21) is equivalent to \( F\left({q}^{*}\right)={\eta}_{\mathrm{SE}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}\right)-{q}^{*}{P}_{\mathrm{T}}\left({P}_{\mathrm{B}},{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}\right)=0 \). Searching q* can be done by the Dinkelbach method which can converge to the optimal value at a superlinear rate [29]. Therefore, for any feasible q, the sub-problem Eq. (21) can be equivalently transformed into a sub-problem Eq. (22), as follows:

The objective function can be calculated as

F q (x) = x(R HD − R FD) + R FD − q[x(P half − P full) + P full], where x ~ [max(b1, b2), min(b3, b4)] ⊂ (0, 1), b1 is taken from \( {R}_{\mathrm{Feeder}}^{\mathrm{HD},k}\ge {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^{\mathrm{HD},k} \), b2 is got from \( {R}_{\mathrm{Feeder}}^{\mathrm{FD},k}\ge {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^{\mathrm{FD},k} \) (obviously, b 2 = max(b 1, b 2)), \( b3=\frac{\overline{\eta_{\mathrm{SE}}}-{R}_{\mathrm{FD}}}{R_{\mathrm{HD}}-{R}_{\mathrm{FD}}} \), and \( b4={e}^{-\frac{a}{\overline{P_{\mathrm{B}}}}} \). From the above description, the objective function can be expressed as

where \( b={R}_{\mathrm{HD}}-{R}_{\mathrm{FD}}+\frac{1}{2}q{a}_{\mathrm{R}}{\displaystyle {\sum}_{k=1}^K{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}},\ c=\frac{1}{2}aq{a}_{\mathrm{B}},\ d={R}_{\mathrm{FD}}-q\left({P}_{\mathrm{C}}+{a}_{\mathrm{R}}{\displaystyle {\sum}_{k=1}^K{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}}\right) \). The first-order derivative of the objective function is \( {F}_q^{\hbox{'}}(x)=b+\frac{g(x)}{x{\left( \ln x\right)}^2} \), where g(x) = − cx ln x + cx − 2c, g '(x) = − c ln x > 0. Obviously, g(x) < 0.

In order to determine whether the first-order derivative of the objective function is positive or negative, we discuss it in the following two cases.

Case 1: b < 0

The first-order derivative of the objective function \( {F}_q^{\hbox{'}}(x) \) will always be less than zero. Hence,

where \( k1=\frac{{\left|{H}_{{\mathrm{R}\mathrm{M}}_k}\right|}^2}{{\displaystyle {\sum}_{j=1,j\ne k}^K{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_j}{\left|{H}_{{\mathrm{R}}_j{\mathrm{M}}_k}\right|}^2+{\sigma}^2}} \).

Case 2: b > 0

The first-order derivative of the objective function is \( {F}_q^{\hbox{'}}(x)=\frac{bx{\left( \ln x\right)}^2-cx \ln x+cx-2c}{x{\left( \ln x\right)}^2} \). Let y(x) = − cx ln x + cx + bx(ln x)2 − 2c, y '(x) = b(ln x)2 + (2b − c)ln x. We can get y '(e t) = bt 2 + (2b − c)t = 0, t = ln x, t < 0. The solution to it is \( {t}_1=0,\kern0.01em {t}_2=\frac{c-2b}{b}. \). Next, we will discuss it under two different conditions:

-

1)

t 2 > 0. We have y '(x) > 0 and \( \underset{x\to 1}{ \lim }y(x)=-c<0 \). Hence, F '(x) < 0, F q (x)max = F q (b2).

-

2)

\( {t}_2<0.\ y{(x)}_{\max }=\left(4b-c\right){e}^{\frac{c-2b}{b}}-2c \).

The above discussion of the positive/negative property of y(x)max is summarized below:

2.2 Optimizing over \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) with a fixed P B

Given a fixed P B, our target is to seek the optimal transmission power \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) to maximize the system energy efficiency while satisfying the above-mentioned constraints. The problem (P) can be rewritten as

With a fixed P B, the sub-problem Eq. (26) is a convex optimization problem for a given q. We now prove the convexity. For a given q, the transformed subtractive form can be written as η SE − qP T. The first part of the subtractive form is η SE which is a concave function in \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) and the second part is an affine function. Since the sum of a concave function and an affine function is also a concave function, the proof of convexity is complete. Therefore, we can derive the optimal solution in an effective way. The partial Lagrangian function of the sub-problem Eq. (26) can be expressed as

where λ 1 is the Lagrangian multiplier associated with the inequality constraints and is required to be non-negative. By using the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions, it is required that the first-order derivative of L EE with respect to \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) be zero, i.e.,

We can obtain

where \( \theta =\frac{q{a}_{\mathrm{R}}}{1+{\lambda}_1} \), []+ guarantees \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k}\ge 0 \).

Note that the sub-optimal transmit power of \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) given by Eq. (28) is similar to customized water-filling solutions, where the heights of the pool are defined as 1/k1 and the water level is partially determined by λ 1 and q. Because \( {P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_k} \) involves the Lagrangian multiplier λ 1 and the KKT conditions require λ 1 to be non-negative, we derive λ 1 in the following two cases:

Case 1: λ 1 > 0

In this case, from the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions, we have \( {\eta}_{\mathrm{SE}}=\overline{\eta_{\mathrm{SE}}} \). We can get \( {\lambda}_1=\frac{ \ln 2*q*{a}_{\mathrm{R}}}{2^a}-1 \), where \( a=\frac{{\displaystyle \sum_{k=1}^K{ \log}_2k1-\frac{2\overline{\eta_{\mathrm{SE}}}}{2-x}}}{K} \). Substituting this positive root back yields the sub-optimal solution of the sub-problem Eq. (26) as

Case 2: λ 1 = 0

In this case,

Note that, this case may break the SE constraint. If this happens, the solution Eq. (29) should be adopted. Otherwise, both Eqs. (29) and (30) are feasible and the one leading to a greater EE is the final solution. In addition, we need to guarantee that the information rate of the feeder link is no lower than that of the access link, i.e., \( {R}_{\mathrm{Feeder}}^k\ge {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^k \). Obviously, the condition to guarantee it for FD is more strict than that for HD. Hence, we only consider the condition \( {R}_{\mathrm{Feeder}}^{\mathrm{FD},k}\ge {R}_{\mathrm{Access}}^{\mathrm{FD},k} \). In this case,

where \( c={\displaystyle {\sum}_{l=1,l\ne k}^K{P}_{{\mathrm{R}}_l}{\left|{H}_{R_{l,k}}\right|}^2}+{\sigma}^2 \). Considering the transmit power constraints, the final solution can be expressed as

2.3 Iterative optimization algorithm

In the alternate optimization method, the basic idea is that the sub-problem Eq. (22) and the sub-problem Eq. (26) are solved in turn to reach the solution to the primal problem (P). For clarity, the detailed procedure of the iterative optimization algorithm is listed in Table 1. From Table 1, in each iteration l, we first set the optimal solution to the sub-problem Eq. (26) in the previous iteration l − 1 as the initial value of the sub-problem Eq. (22). Then, we solve the sub-problem Eq. (22) and output the optimal solution P B in Eq. (22) as the initial value of the sub-problem Eq. (26). The process is repeated until convergence is attained, i.e., |q (k) − q (k − 1)| is smaller than a predefined threshold ε 0.

3 Simulation results

The MATLAB tool is adopted to simulate the energy efficiency of the relay-aided cellular network under various system parameters and verify the effectiveness of the hybrid scheme. Here, the cell bandwidth has been normalized to 1 Hz. Some simulation parameters are specified in Table 2.

The distance between the BS and a RS is set to d RS = 0.7R in the cell. The distance between the RS and a MU is set to d ∼ U[0, 0.3R], and the interference distance among the RSs is set to d ∼ U[0.5R, 1.7R], where U[] represents the uniform distribution.

As shown in Fig. 2a, under perfect SI cancellation, the hybrid scheme approaches to the FD mode. That is to say, the probability of hybrid transmission selecting HD will be very low. With the increase of SI, the performance of FD begins to deteriorate, and the hybrid scheme moves toward HD. Under poor SI cancellation, the hybrid scheme tends to the HD mode. Hence, the probability of hybrid transmission selecting HD will be close to 1.

Figure 2b shows the effect of SI channel gain on energy efficiency. It is clear that energy efficiency in the HD mode is a fixed value due to no SI. Note that energy efficiency is defined as the ratio of spectral efficiency to total power consumption. Under perfect SI cancellation, because the throughput in the FD mode is twice of that in the HD mode, the FD mode can achieve higher energy efficiency than the HD mode. Combining Figs. 2a, b, under perfect SI cancellation, the hybrid schemes adopts the FD mode basically, and takes the throughput advantage of FD to achieve higher energy efficiency than the HD mode, which is close to that of the FD mode. With the increase of SI, the performance of FD starts to deteriorate, but the energy efficiency in the hybrid scheme is between those of the HD and the FD schemes. Nearly in G = −45 dB, the energy efficiency in the FD mode starts to be less than the energy efficiency in the HD mode. At this point, because the probability of hybrid transmission selecting HD is greater than that selecting FD, the throughput of the system reduces. However, the total power consumption does not reduce obviously, which leads to the fact that the energy efficiency in the hybrid scheme is less than that in the HD or FD mode. With the increase of SI channel gain, the energy efficiency in the FD mode is lower than that in the hybrid scheme. While the SI becomes large, due to the strong SI of FD, it cannot work normally. Hence, the energy efficiency in the FD mode is close to 0, and the probability of hybrid transmission selecting HD is close to 1. Even in the case of strong SI, the energy efficiency in the hybrid scheme can be much better than that in the FD mode.

In Fig. 2a, b, the static power consumption of the BS and the RSs (b B and b R) are set to 120 and 22 W, respectively. Next, we will show the effect of SI channel gain on energy efficiency under the condition of b B = 10 W and b R = 1 W, and the other parameters are the same as before, as shown in Figs. 3a, b.

Obviously, the static power consumption reduces and the energy efficiency of the system increases. However, the trend of energy efficiency versus SI channel gain does not change.

Figure 4a, b shows the influence of the cell radius on the energy efficiency under the conditions of G = − 20 dB and G = − 60 dB, respectively. Taking the actual scenario into account, the cell radius varies from 700 to 1500 m. From Figs. 4a, b we can see: in the case of G = − 20 dB, the energy efficiency in the FD mode is lower than that in the HD mode. In the case of G = − 60 dB, the energy efficiency in the FD mode is higher than that in the HD mode. The energy efficiency in the hybrid scheme is between those in the HD and the FD modes. Comparing Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b, in the same cell radius, since there is no SI in HD, the energy efficiency is the same; in the case of G = − 60 dB, the energy efficiency in the FD mode and the hybrid scheme are higher than those in the case of G = − 20 dB, respectively. In addition, with the increase of cell radius, the energy efficiency of the system gradually reduces in the three transmission modes.

Figure 5 illustrates the convergence of the iterative optimization algorithm in the condition of G = − 60 dB and the other parameters are the same as before. It can be seen that the proposed algorithm can converge quickly.

4 Conclusions

In this paper, a hybrid HD/FD transmission scheme in a relay-aided cellular network has been presented, taking SI cancellation into account. An optimization problem was formulated to maximize the system energy efficiency under the system spectral efficiency constraint as well as the transmit power constraints of BS and RSs. The alternate optimization method was used to solve the optimization problem and obtain the optimal transmit powers. Simulation results showed that the hybrid scheme not only takes the throughput advantage of FD, but also weakens the negative effect of SI.

References

R Pabst, B Walke, D Schultz et al., Relay-based deployment concepts for wireless and mobile broadband radio. IEEE Commun. Maga. 42(9), 80–89 (2004)

N Lee, D Morales-Jimenez, A Lozano, RW Health, Spectral efficiency of dynamic coordinated beamforming: a stochastic geometry approach. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 14(1), 230–241 (2015)

K Xu, X Yi, Y Gao, G Zang, Outage analysis of dual-hop Alamouti transmission with channel estimation error. Trans. Emerging. Tel. Tech. 23(4), 393–398 (2012)

B Radunovic, A Proutiere, On downlink capacity of cellular data network with WLAN/WPAN relays. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 21(1), 286–296 (2013)

“Full duplex configuration of Un and Uu subframes for type I relay,” 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 R1-100139, Tech. Report, 2010.

“Text proposal on inband full duplex relay for TR 36.814,” 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 R1-101659, Tech. Report, 2010.

H Ju, E Oh, D Hong, Improving efficiency of resource usage in two-hop full duplex relay systems based on resource sharing and interference cancellation. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 8(8), 3933–3938 (2009)

T Kwon, S Lim, S Choi, D Hong, Optimal duplex mode for DF relay in terms of the outage probability. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 59(7), 3628–3634 (2010)

T Riihonen, S Werner, R Wichman, Optimized gain control for single-frequency relaying with loop interference. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 8(6), 2801–2806 (2009)

T Riihonen, S Werner, R Wichman, Mitigation of loopback self-interference in full-duplex MIMO relays. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 59(12), 5983–5993 (2011)

S Hong, J Brand, JII Choi, M Jain, J Mehlman, S Katti, P Levis, Applications of self-interference cancellation in 5G and beyond. IEEE Commun. Maga. 52(2), 114–121 (2014)

E Everett, A Sahai, A Sabharwal, “Passive self-interference suppression for full-duplex infrastructure nodes”. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 13(2), 680–694 (2014)

D Korpi, L Anttila, V Syrjala, M Valkama, Widely linear digital self-interference cancellation in direct-conversion full-duplex transceiver. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 32(9), 1674–1687 (2014)

JH Yun, Intra and inter-cell resource management in full-duplex heterogeneous cellular networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 15(2), 392–405 (2016)

G Liu, FR Yu, H Ji, VCM Leung, Virtual resource management in green cellular networks with shared full-duplex relaying and wireless virtualization: a game-based approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 65(9), 7529–7542 (2016)

G Zhang, K Yang, P Liu, J Wei, Power allocation for full-duplex relaying based D2D communication underlaying cellular networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 64(10), 4911–4916 (2015)

GY Li, Z Xu, C Xiong, C Yang, S Zhang, Y Chen, S Xu, Energy-efficient wireless communications: tutorial, survey, and open issues. IEEE Wireless Commun. 18(6), 28–35 (2011)

JB Rao, AO Fapojuwo, “A survey of energy efficient resource management techniques for multicell cellular networks”. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 16(1), 154–180 (2014)

H Chen, G Li, and J Cai, “Spectral-energy efficiency tradeoff in full-duplex two-way relay networks,”. IEEE Syst. J. 2015, pp. 1–10

G Liu, FR Yu, H Ji, VCM Leung, Energy-efficient resource allocation in cellular networks with shared full-duplex relaying. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 64(8), 3711–3724 (2015)

X Jia, P Deng, L Yang, H Zhu, Spectrum and energy efficiencies for multiuser pairs massive MIMO systems with full-duplex amplify-and-forward relay. IEEE Access. 3, 1907–1918 (2015)

Z Zhang, Z Chen, M Shen, B Xia, Spectral and energy efficiency of multi-pair two-way full-duplex relay systems with massive MIMO. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 34(4), 848–863 (2016)

K Yamatomo, K Haneda, H Murata, S Yoshida, Optimal transmission scheduling for a hybrid of full- and half-duplex relaying. IEEE Commun. Lett. 15(3), 305–307 (2011)

T Riihonen, S Werner, R Wichman, Hybrid full-duplex/half-duplex relaying with transmit power adaptation. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 10(9), 3074–3085 (2011)

J Lee, TQS Quek, Hybrid full-/half-duplex system analysis in heterogeneous wireless networks. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 14(5), 2883–2895 (2015)

Y Li, T Wang, Z Zhao, M Peng, W Wang, Relay mode selection and power allocation for hybrid one-way/two-way half-duplex/full-duplex relaying. IEEE. Commun. Lett. 19(7), 1217–1220 (2015)

A. Fehske, F. Richter, and G. Fettweis, “Energy efficiency improvements through micro sites in cellular mobile radio networks,” in Proc. IEEE GLOBECOM Workshops, 2009, pp. 1-5

O. Arnold, F. Richter, G. Fettweis, and O. Blume, “Power consumption modeling of different base station types in heterogeneous cellular networks,” in Proc. Future Network & Mobile Summit, 2010, pp. 1-8.

S Schaible, T Ibaraki, Fractional programming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 12(4), 325–338 (1983)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61471135, 61671165), the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2013GXNSFGA019004, 2015GXNSFBB139007), the Fund of Key Laboratory of Cognitive Radio and Information Processing (Guilin University of Electronic Technology), Ministry of Education, China, and Guangxi Key Laboratory of Wireless Wideband Communication and Signal Processing (CRKL150104, CRKL160105).

Authors’ contributions

CHB carried out the system model and algorithm design. ZF participated in the mathematical derivation and simulation. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Zhao, F. A hybrid half-duplex/full-duplex transmission scheme in relay-aided cellular networks. J Wireless Com Network 2017, 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-016-0795-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-016-0795-x