Abstract

Background

Evaluation of fluid responsiveness during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support is crucial. The aim of this study was to investigate whether changes in left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral (ΔVTI), induced by a Trendelenburg maneuver, could predict fluid responsiveness during VA-ECMO.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted in patients with VA-ECMO support. The protocol included four sequential steps: (1) baseline-1, a supine position with a 15° upward bed angulation; (2) Trendelenburg maneuver, 15° downward bed angulation; (3) baseline-2, the same position as baseline-1, and (4) fluid challenge, administration of 500 mL gelatin over 15 min without postural change. Hemodynamic parameters were recorded at each step. Fluid responsiveness was defined as ΔVTI of 15% or more, after volume expansion.

Results

From June 2018 to December 2019, 22 patients with VA-ECMO were included, and a total of 39 measurements were performed. Of these, 22 measurements (56%) met fluid responsiveness. The R2 of the linear regression was 0.76, between ΔVTIs induced by Trendelenburg maneuver and the fluid challenge. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of ΔVTI induced by Trendelenburg maneuver to predict fluid responsiveness was 0.93 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81–0.98], with a sensitivity of 82% (95% CI 60–95%), and specificity of 88% (95% CI 64–99%), at a best threshold of 10% (95% CI 6–12%).

Conclusions

Changes in VTI induced by the Trendelenburg maneuver could effectively predict fluid responsiveness in VA-ECMO patients.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT 03553459 (the TEMPLE study). Registered on May 30, 2018

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is a rescue therapy for patients with refractory cardiogenic shock [1, 2]. During VA-ECMO support, hypotension may frequently occur due to deteriorated cardiac function, vasoplegia, or hypovolemia [3, 4]. Volume expansion is a common means to correct hypotension and improve systemic perfusion, but inappropriate fluid therapy is associated with adverse outcomes [5]. Prediction of fluid responsiveness before fluid resuscitation could achieve a lower fluid balance, reduce the risk of renal and respiratory failure, and improve outcomes for critically ill patients [6].

Several methods are currently available to evaluate fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients [7,8,9]. Mechanical ventilation generates a cyclical change in intra-thoracic pressure and venous return. Based on this interaction, stroke volume variation (SVV) and pulse pressure variation (PPV) are often used as dynamic parameters to predict fluid responsiveness [8]. However, VA-ECMO patients frequently present with low tidal volume, cardiac arrhythmia and especially pulselessness, thus making these parameters less reliable [8, 10, 11]. Respiratory variations in the inferior vena cava diameter (ΔIVCD) have previously been used as accurate predictors for fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients [12]. However, drainage cannulation placed in the inferior vena cava impedes the application of ΔIVCD. Simulation of a revisable “autotransfusion” is another feasible approach to assess fluid responsiveness. Passive leg raising (PLR) test transiently increases venous return by postural maneuver [8]. Unfortunately, the risk of cannula distortion or displacement precluded the application of this maneuver to VA-ECMO patients. Overall, the physiological features of VA-ECMO patients restrict the use of conventional methods to assess fluid responsiveness [11].

The Trendelenburg maneuver is a “self” volumetric loading maneuver [13], and has demonstrated good accuracy in predicting responsiveness for acute respiratory distress syndrome [14] and surgical patients [15], and can be performed for the majority of VA-ECMO patients. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is now routinely used to evaluate cardiac function recovery, and allows the measurement of stroke volume and cardiac output in VA-ECMO patients [16]. Thus, the combination of the Trendelenburg maneuver and TTE facilitates the evaluation of fluid responsiveness during VA-ECMO support.

This study was designed to investigate whether a change in velocity–time integral (ΔVTI) measured by TTE induced by the Trendelenburg maneuver, could predict fluid responsiveness in patients on VA-ECMO.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China: Number B2018-074), and conducted in a 40-bed cardiac surgical intensive care unit (ICU). During the study period (June 2018–December 2019), 22 postoperative patients were prospectively enrolled after informed consent was received from the patient’s next of kin. We included ventilated patients with relatively low VA-ECMO pump flow (2–3 L/min) for whom the decision to perform volume expansion was made by the attending physician (hypotension, hypoperfusion [oliguria or skin mottling], or attempt to reduce vasopressor dose [17, 18]). Exclusion criteria were patients < 18 years old, pregnant, pulselessness (pulse pressure (PP) < 15 mmHg [19]), contraindication to the Trendelenburg position (cerebral edema, intra-abdominal hypertension and gastric retention), or unsatisfactory cardiac echogenicity (an inability to correctly align the Doppler beam to generate reliable VTI measurements at the left ventricular outflow tract [LVOT]). Patients with evidence of significant hypovolemia, such as kicking drainage cannula [20] (suggesting a transient venous or atrial collapse) and persistent hemorrhage, were also excluded.

Protocol

Throughout the study, patients were sedated with a combination of remifentanil and midazolam, with the aim of achieving a Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale [21] of − 5. The protocol included four sequential steps (Fig. 1):

-

1.

Baseline-1: a supine position with a 15° upward bed angulation,

-

2.

Trendelenburg maneuver: 15° downward bed angulation [22],

-

3.

Baseline-2: recover to the same position as baseline-1, and

-

4.

Fluid challenge: administration of 500 mL gelatin over 15 min without postural change.

After 1 min stabilization for each step, VTI, heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), central venous pressure (CVP) and pulse pressure (PP) were recorded. In our center, the tip of the drainage cannula was placed in the right atrium to guarantee adequate blood collection [11]. The pressure transducer was fixed at the level of the patient’s right atrium, which was located at the intersection of the mid-axillary line and the fourth interspace. During the study, the pump was maintained at the same rotation speed. Other therapies such as sedation, vasopressors and ventilation also remained unchanged. To acquire as much data as feasible, some patients underwent the test more than once (on different days) if required, therefore 39 measurements were conducted and recorded.

VTI measurements

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on a CX50 instrument (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) by the same experienced operator (LL Dong) who was blinded to patient clinical data. VTI was measured at the level of the LVOT, using the 5-chamber apical view. Five consecutive measurements were recorded to calculate a mean VTI value. For TTE measurement, some indices were defined to estimate the reproducibility [17, 23]: (1) coefficient of variation (CV) = standard deviation (SD)/mean; (2) coefficient of error (CE) = CV/√n (the number of replicate TTE); (3) precision = 2 × CE; (4) least significant change (LSC) = CE × 1.96 × √2, indicting the minimal observed change value can be considered as real. These assessments were performed in eight patients at baseline position by obtaining twice by the same operator (LL Dong; intra-observer reproducibility) and a second operator (Y Liu; inter-observer reproducibility). The CV was 4% for intra-observer variability, and 5% for inter-observer variability. The intra-observer LSC was 8% for VTI measurements.

Data collection

Upon patient inclusion, demographic information, surgical procedures, Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), laboratory examinations and blood gas analyses were collected. Supportive therapies included VA-ECMO and mechanical ventilation (MV) indices, vasoactive drug doses (transferred to equivalent inotropic scores) [24], and the concomitant use of intra-aortic balloon pumps (IABP), renal replacement therapy (RRT) or inspired nitric oxide (iNO). We recorded all data related to these parameters. All study patients were followed up until hospital discharge or death, to record clinical outcomes, such as length of MV, tracheotomy rate, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay and hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation was performed using PASS software. We used the following settings: AUC0 = 0.5, AUC1 = 0.80, power = 0.9, alpha = 0.05, allocation ratio = 1, lower false positive rate (FPR) = 0, upper FPR = 1.00, type of data = continuous, and alternative hypothesis = two-sided test, therefore the least number of measurements required was 34.

Continuous variables were expressed as medians (with interquartile ranges [IQR]) and compared between groups using the Wilcoxon or Friedman rank sum tests. For pairwise multiple comparisons, we used the Nemenyi post hoc test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (and percentages) and compared using the Fisher's exact test. Linear regression analysis was used to demonstrate relationships between percent change of VTI (ΔVTI) induced by the Trendelenburg position, and fluid challenge. Fluid responsiveness was defined as a VTI increase of 15% or more after volume expansion [17].

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to evaluate percent changes in VTI and arterial pressure parameters (ΔSBP, ΔDBP and ΔPP), induced by the Trendelenburg maneuver to predicts fluid responsiveness. The area under ROC curves (AUROC) were compared using the DeLong test [25]. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated based on the cutoff value as determined by the Youden Index (specificity + sensitivity − 1) [26]. To evaluate the variation of best threshold, we conducted a gray-zone analysis, as described by Georges et al. [17]. To visualize whether a predictive test can recognize the positive events fully and accurately, the recall (i.e., true positive rate)-precision (i.e., PPV) curves (PRC) were generated and area under precision–recall curve (AUPRC) were calculated [27].

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients

The study flowchart is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. Due to unavailability of echocardiography staff in personal vacations, the study period became inconsecutive and 3 patients were not included. Besides, 3 (9%) patients were excluded for poor echogenicity. The main characteristics of the 22 enrolled patients are shown (Table 1). The major surgical procedures were heart transplantation (45%), valve surgery (32%), and Sun’s procedure [28] (14%). The median length of VA-ECMO support was 6 days (IQR 4–10), and 17 patients (77%) were weaned from VA-ECMO. IABP, RRT and iNO were performed in 1 (5%), 11 (50%) and 13 (59%) patients, respectively. The median length of MV was 16 days (IQR 7–23), and 14 patients (64%) underwent a tracheotomy. Eight patients (36%) died during a median length stay of 20 days (IQR 14–36) in ICU.

Measurements

Thirty-nine measurements were performed at a median of 4 days (IQR 3–5) after VA-ECMO support initiation (Table 2). Of these measurements, volume expansions were decided for hypotension, oliguria, skin mottling, and attempt to reduce vasopressor dose in 30 (77%), 4 (10%), 1 (3%) and 4 (10%) measurements, respectively. All laboratory examinations and supportive therapies are presented (Table 2). ECMO flow, tidal volume, and equivalent inotropic scores were 2.4 L/min (IQR 2.2–2.8), 7.0 mL/kg (IQR 6.7–7.6), and 6 μg/kg/min (IQR 1–12), respectively. During the study protocol, no patients developed cannula-related complications (i.e., hemorrhages, thrombosis or cannula displacement) following the Trendelenburg maneuver.

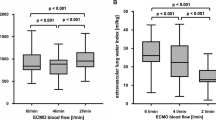

The effects of the Trendelenburg maneuver and fluid challenge

Fluid responsiveness was observed in 22 of the 39 measurements (56%). Hemodynamic parameters from each step are shown (Table 3 and Fig. 3a, b). Higher baseline CVP was observed in non-responders. No variables recorded after return to baseline values exhibited significant differences. CVP, SBP, DBP, PP, and VTI indices were higher for either Trendelenburg or fluid challenges than their corresponding baseline values. The fluid challenge induced higher ΔSBP (9% [IQR 5–18%] vs. 8% [IQR 4–14%], p = 0.019), ΔPP (17% [IQR 1–21%] vs. 12% [IQR 4–21%], p = 0.044), and ΔVTI (16% [IQR 4–30%] vs. 10% [IQR 5–21%], p < 0.001) than the Trendelenburg maneuver. The ΔVTI between the Trendelenburg position and fluid challenge was highly related, with an R2 of 0.7614 and a slope of 0.58 (Fig. 2a). In comparison, the R2 of ΔSBP, ΔDBP and ΔPP were 0.2167, 0.0715 and 0.2187, respectively (Fig. 2b–d).

Linear regression between changes in velocity–time integral (ΔVTI, a), systolic blood pressure (ΔSBP, b), diastolic blood pressure (ΔDBP, c) and pulse pressure (ΔPP, d) induced by the Trendelenburg position and the fluid challenge. Solid and dashed lines indicate regression lines and their 95% confidential intervals

Prediction of fluid responsiveness

Data on fluid responsiveness predictions are shown (Fig. 3 C&D, Additional file 1: Figure S2 and Table 4). The AUROC of ΔVTI induced by Trendelenburg to predict fluid responsiveness was 0.93 (95% CI 0.81–0.98), with a sensitivity of 82% (95% CI 60–95%), and specificity of 88% (95% CI 64–99%), at a best threshold of 10%. The corresponding gray-zone was 6–12%, covering 32% of measurements. The percent change in arterial pressure variables, i.e., ΔSBP, ΔDBP and ΔPP, displayed lower predictive accuracies (AUROCs: 0.76 [95% CI 0.56–0.87], 0.73 [95% CI 0.52–0.85] and 0.69 [95% CI 0.48–0.82], respectively), whereas wider ranges of best thresholds (13% [95% CI 6–14%], 6% [95% CI 2–13%] and 10% [95% CI 2–23%]) than ΔVTI. Also, the ΔVTI showed higher AUPRC (0.96 [95% CI 0.88–0.99]) than ΔPP (0.70 [95% CI 0.61–0.92]), ΔSBP (0.85 [95% CI 0.71–0.95]) and ΔDBP (0.80 [95% CI 0.61–0.94]) (Additional file 1: Figure S3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the predictive value of ΔVTI, induced by the Trendelenburg position for fluid responsiveness in patients with VA-ECMO support. Our work demonstrated that ΔVTI monitoring during the Trendelenburg position was a reliable parameter in predicting fluid responsiveness in this population.

VA-ECMO could provide extracorporeal life support, as well as reducing the workload of the injured heart, thereby creating favorable conditions for myocardial recovery [1, 2]. During this support, clinicians usually increase ECMO flow to correct hypotension, which would lead to a higher left ventricular afterload and a downward shift of the Frank–Starling curve [29]. Apart from device flow, native cardiac output also plays an important role in maintaining systemic circulation, especially when the heart is in recovery, and device flow decreases correspondingly. Moreover, the volume status of the heart varies at any time due to hemorrhage, capillary leak, fluid therapy and changes in cardiac function, and hence should be dynamically evaluated.

Fluid responsiveness, as a cardiac response parameter to additional preload, is typically used for septic shock patients [8]; however, it may also be useful for patients with VA-ECMO support. On one hand, during VA-ECMO support, traditional parameters such as ejection fraction may not fully reflect cardiac function [30]. Fluid responsiveness may indicate whether the heart works at the steeper part of the Frank–Starling curve, thus guiding volume administration for hypotension, thereby providing indications for myocardial recovery and weaning feasibility from VA-ECMO. On the other hand, fluid unresponsiveness could also be used to guide fluid removal in ventilated patients with fluid overload [31], which may induce heart congestion, pulmonary edema, and acute kidney injury [32, 33], potentially increasing mortality [34]. Hence, assessment of fluid responsiveness could help to optimize preload and also evaluate cardiac function.

The Trendelenburg maneuver is a method that facilitates “autotransfusion”. Geerts et al. concluded that the final changes in cardiac output induced by the Trendelenburg position were similar to PLR [13]. In this study, the Trendelenburg position induced a 58% change in VTI, induced by a 500-mL fluid challenge, indicating a similar physiological effect to PLR. The high correlation between changes in VTI induced by the Trendelenburg position or fluid challenge allowed us to accurately predict fluid responsiveness in VA-ECMO patients.

Arterial pulsatility, coming from left ventricular ejection, is often considered as a marker of cardiac recovery during VA-ECMO [4, 35]. PP, as a parameter of pulsatile-flow, has been used as a predictor of successful weaning from VA-ECMO [36, 37]. However, in this study, changes in PP had a poorer predictive performance for fluid responsiveness than VTI. Although both variables could reflect the stroke volume, the PP is just a difference between SBP and DBP, rather than the area under the pulse contour per se. In fact, the relationship between SV and peripheral PP changes were not straightforward because they depended on arterial compliance, and pulse wave amplification from the aorta to the periphery. Previous studies have indicated that changes in PP exerted significant heterogeneity towards predictive accuracy for fluid responsiveness [38, 39]. Similarly, neither ΔSBP nor ΔDBP, induced by the Trendelenburg maneuver, demonstrated an acceptable predictive accuracy in this study.

Study limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single center, which may have limited generalizability across different clinical settings. Second, a larger angle of Trendelenburg positioning may have introduced more “autotransfusion” to the central circulation [13], and was not evaluated in this study. Third, measurement of LVOT VTI is not the gold standard for evaluating cardiac output, because of its dependence on patient echogenicity and operator expertise. However, techniques based on thermodilution have proven unreliable in VA-ECMO patients [3], although they were accurate in estimating cardiac output under most circumstances [40]. Fourth, all patients in this study were under deep sedation, thus the Trendelenburg maneuver may be less reliable in predicting fluid responsiveness in non-sedated patients. Finally, because the study was conducted in a low VA-ECMO pump flow setting, our data may not be extrapolated to the acute phase of heart failure requiring full mechanical circulatory support.

Conclusions

Our study suggested that an increase in VTI of at least 10%, induced by the Trendelenburg maneuver, was reliable in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients with VA-ECMO.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- VA-ECMO:

-

Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- SVV:

-

Stroke volume variation

- PPV:

-

Pulse pressure variation

- ΔIVCD:

-

Respiratory variations in the inferior vena cava diameter

- PLR:

-

Passive leg raising

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

- VTI:

-

Velocity–time integral

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure

- PP:

-

Pulse pressure

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- LSC:

-

Least significant change

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- iNO:

-

Inspired nitric oxide

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive values

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive values

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- PRC:

-

Precision–recall curves

References

Pineton de Chambrun M, Brechot N, Combes A. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock: indications, mode of operation, and current evidence. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25:397–402.

Rao P, Khalpey Z, Smith R, Burkhoff D, Kociol RD. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004905.

Krishnan S, Schmidt GA. Hemodynamic monitoring in the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patient. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25:285–91.

Ortuno S, Delmas C, Diehl JL, Bailleul C, Lancelot A, Naili M, et al. Weaning from veno-arterial extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation: which strategy to use? Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:E1–8.

Messmer AS, Zingg C, Muller M, Gerber JL, Schefold JC, Pfortmueller CA. Fluid overload and mortality in adult critical care patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1862–70.

Douglas IS, Alapat PM, Corl KA, Exline MC, Forni LG, Holder AL, et al. Fluid response evaluation in sepsis hypotension and shock: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2020;158:1431–45.

Monnet X, Marik PE, Teboul JL. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: an update. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:111.

Jozwiak M, Monnet X, Teboul JL. Prediction of fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:352.

Monnet X, Teboul JL. Assessment of fluid responsiveness: recent advances. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24:190–5.

Araos J, Kenny JS, Rousseau-Blass F, Pang DS. Dynamic prediction of fluid responsiveness during positive pressure ventilation: a review of the physiology underlying heart-lung interactions and a critical interpretation. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2020;47:3–14.

Su Y, Liu K, Zheng JL, Li X, Zhu DM, Zhang Y, et al. Hemodynamic monitoring in patients with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:792.

Huang H, Shen Q, Liu Y, Xu H, Fang Y. Value of variation index of inferior vena cava diameter in predicting fluid responsiveness in patients with circulatory shock receiving mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2018;22:204.

Geerts BF, van den Bergh L, Stijnen T, Aarts LP, Jansen JR. Comprehensive review: is it better to use the Trendelenburg position or passive leg raising for the initial treatment of hypovolemia? J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:668–74.

Yonis H, Bitker L, Aublanc M, Perinel Ragey S, Riad Z, Lissonde F, et al. Change in cardiac output during Trendelenburg maneuver is a reliable predictor of fluid responsiveness in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in the prone position under protective ventilation. Crit Care. 2017;21:295.

Frost H, Mortensen CR, Secher NH, Nielsen HB. Postoperative volume balance: does stroke volume increase in Trendelenburg’s position? Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2017;37:314–6.

Expert Round Table on Ultrasound in ICU. International expert statement on training standards for critical care ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1077–83.

Georges D, de Courson H, Lanchon R, Sesay M, Nouette-Gaulain K, Biais M. End-expiratory occlusion maneuver to predict fluid responsiveness in the intensive care unit: an echocardiographic study. Crit Care. 2018;22:32.

Cecconi M, Hofer C, Teboul JL, Pettila V, Wilkman E, Molnar Z, et al. Fluid challenges in intensive care: the FENICE study: a global inception cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1529–37.

Brechot N, Demondion P, Santi F, Lebreton G, Pham T, Dalakidis A, et al. Intra-aortic balloon pump protects against hydrostatic pulmonary oedema during peripheral venoarterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7:62–9.

Le Gall A, Follin A, Cholley B, Mantz J, Aissaoui N, Pirracchio R. Veno-arterial-ECMO in the intensive care unit: from technical aspects to clinical practice. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018;37:259–68.

Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289:2983–91.

Nassar B, Deol GRS, Ashby A, Collett N, Schmidt GA. Trendelenburg position does not increase cross-sectional area of the internal jugular vein predictably. Chest. 2013;144:177–82.

Jozwiak M, Mercado P, Teboul JL, Benmalek A, Gimenez J, Depret F, et al. What is the lowest change in cardiac output that transthoracic echocardiography can detect? Crit Care. 2019;23:116.

Lin TW, Tsai MT, Hu YN, Lin WH, Wang WM, Luo CY, et al. Postoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for acute type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:827–33.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45.

Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–5.

Keilwagen J, Grosse I, Grau J. Area under precision–recall curves for weighted and unweighted data. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92209.

Sun L, Qi R, Zhu J, Liu Y, Zheng J. Total arch replacement combined with stented elephant trunk implantation: a new “standard” therapy for type a dissection involving repair of the aortic arch? Circulation. 2011;123:971–8.

Dickstein ML. The starling relationship and veno-arterial ECMO: ventricular distension explained. ASAIO J. 2018;64:497–501.

Morimont P, Lambermont B, Guiot J, Tchana Sato V, Clotuche C, Goffoy J, et al. Ejection fraction may not reflect contractility: example in veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for heart failure. ASAIO J. 2018;64:e68–71.

Monnet X, Cipriani F, Camous L, Sentenac P, Dres M, Krastinova E, et al. The passive leg raising test to guide fluid removal in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:46.

Miller WL. Fluid volume overload and congestion in heart failure: time to reconsider pathophysiology and how volume is assessed. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002922.

Claure-Del Granado R, Mehta RL. Fluid overload in the ICU: evaluation and management. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:109.

Besnier E, Boubeche S, Clavier T, Popoff B, Dureuil B, Doguet F, et al. Early positive fluid balance is associated with mortality in patients treated with veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock: a retrospective cohort study. Shock. 2020;53:426–33.

Vincent F, Rauch A, Loobuyck V, Robin E, Nix C, Vincentelli A, et al. Arterial pulsatility and circulating von Willebrand factor in patients on mechanical circulatory support. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2106–18.

Park BW, Seo DC, Moon IK, Chung JW, Bang DW, Hyon MS, et al. Pulse pressure as a prognostic marker in patients receiving extracorporeal life support. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1404–8.

Aissaoui N, Luyt CE, Leprince P, Trouillet JL, Leger P, Pavie A, et al. Predictors of successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) weaning after assistance for refractory cardiogenic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1738–45.

De la Puente-Diaz de Leon V, de Jesus Jaramillo-Rocha V, Teboul JL, Garcia-Miranda S, Martinez-Guerra BA, Dominguez-Cherit G. Changes in radial artery pulse pressure during a fluid challenge cannot assess fluid responsiveness in patients with septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35:149–53.

Dufour N, Chemla D, Teboul JL, Monnet X, Richard C, Osman D. Changes in pulse pressure following fluid loading: a comparison between aortic root (non-invasive tonometry) and femoral artery (invasive recordings). Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:942–9.

Wetterslev M, Moller-Sorensen H, Johansen RR, Perner A. Systematic review of cardiac output measurements by echocardiography vs. thermodilution: the techniques are not interchangeable. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1223–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yu Liu, MD (Department of Echocardiography) for helping us to evaluate the intra-observer variability of TTE and Qin-yu Zhao (Australian National University) for his help in statistical analyses.

Funding

This article was supported by grants from the Research Funds of Zhongshan Hospital (2019ZSQN13 and XYYX201922), the Research Funds of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2019ZB0105), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (20ZR1411100), Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (20XD1421000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070085), Clinical Research Funds of Zhongshan Hospital (2020ZSLC38 and 2020ZSLC27) and Smart Medical Care of Zhongshan Hospital (2020ZHZS01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL, YS, GT and ZL conceived the idea for the manuscript, and drafted and approved the final version. JL, LD, YS and JH had full access to all study data, and accepted responsibility for data integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. JL and GT performed the data analysis and patient recruitment. All authors were involved in data interpretation, and made critical revisions of the manuscript in terms of intellectual input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics committee of Zhongshan hospital, Shanghai, China. Number B2018-074).

Consent for publication

The manuscript has been read and its submission approved by all coauthors. Patients were prospectively included after informed consent from the patient’s next of kin.

Competing interests

All authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Study flowchart. Figure S2. Receiver operating characteristics curves and grey zone analyses. Figure S3. The precision–recall curves for changes in VTI, PP, SBP and DBP induced by Trendelenburg maneuver.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Jc., Su, Y., Dong, Ll. et al. Trendelenburg maneuver predicts fluid responsiveness in patients on veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann. Intensive Care 11, 16 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-021-00811-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-021-00811-x