Abstract

Purpose

To analyse the usefulness of the composite index of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) as urinary biomarkers for the early prediction of AKI in septic and non-septic patients.

Methods

This is a prospective, observational study including patients admitted to ICU from acute care departments and hospital length of stay <48 h. The main exclusion criteria were pre-existing eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and hospitalisation 2 months prior to current admission. The [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index was analysed twice, within the first 12 h of ICU admission.

Results

The sample included 98 patients. AKI incidence during ICU stay was 50%. Sepsis was diagnosed in 40.8%. Baseline renal variables were comparable between subgroups except for a higher baseline eGFR in non-septic patients. Patients were stratified based on the presence of AKI and their highest level of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] within the first 12 h of stay. [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index values were dependent on the incidence of AKI but not of sepsis. [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] values were significantly related to AKI severity according to AKIN criteria (p < 0.0001). The AUROC curve to predict AKI of the worst [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index value was 0.798 (sensitivity 73.5%, specificity 71.4%, p < 0.0001). Index values below 0.8 ruled out any need for renal replacement (NPV 100%), whereas an index >0.8 predicted a rate of AKI of 71% and AKIN ≥ 2 of 62.9%.

Conclusions

In our study, urinary [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] was an early predictor of AKI in ICU patients regardless of sepsis. Besides, index values <0.8(ng/mL)2/1000 ruled out the need for renal replacement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a frequent complication in ICU patients [1]. AKI definitions based on serum creatinine (sCr) have shown a large variation in AKI incidence and associated outcomes [2]. However, it has been observed that AKI requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) is an independent factor of poor outcome [3, 4], with an associated mortality rate of 50–60% [2, 3].

Sepsis is a relevant contributing factor to AKI development. AKI is present in >30% of those with sepsis [5, 6] and in >50% of those with septic shock [7, 8]. Pathogens producing sepsis and their toxins affect the whole body as well as specific organs. Damaging molecules can reach the proximal renal tubular cells in high concentrations and may trigger kidney injury followed by inflammation and oxidative stress and, finally, cell damage [9].

Diagnosis of AKI has changed in the last decade with the advent of RIFLE [10], AKIN [11] and KDIGO [12] classifications. These tools are based on sCr and diuresis. However, sCr is a late and non-specific AKI biomarker [13, 14]. Biomarkers that can rapidly and specifically recognise AKI are therefore needed. A few recent studies have shown that tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) are specific biomarkers of structural renal damage in critically ill patients [15, 16]. Renal tubular cells enter in G1 cell arrest to block the effects of molecules contributing to cell-cycle promotion, such as cyclins. This mechanism prevents the extension of cell damage. TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 are protective molecules involved in G1 cell-cycle arrest that moderate apoptotic, angiogenic [17], inflammatory [18, 19] and ischaemic processes [20]. Since renal cell arrest usually occurs 24–48 h before sCr rises due to a significant fall in the glomerular filtration rate, TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 are thought to be earlier AKI biomarkers than sCr.

TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 are detectable in urine. Previous studies in unselected ICU populations have shown that when analysed together as the index [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7], they perform better than sCr, urine and plasma NGAL, plasma cystatin-C and KIM-1 for early detection of AKI and improved risk stratification for renal and general outcomes [15, 16]. The aim of this study was to assess whether values of the TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 index were early predictors of AKI in a selected ICU population free of the most frequent AKI risk factors. To date, the influence of sepsis on TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 expression in critically ill patients is not well defined. As a secondary objective, we thus also evaluated the potential usefulness of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index in septic ICU patients.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating centre. We obtained informed consent from patients or their guardians. The study prospectively included patients over 18 years of age with an expected ICU stay of at least 48 h. We included patients admitted to ICU either from the emergency department or after undergoing acute surgery. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, established anuric AKI, pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and current hospital length of stay >48 h. Medical management was left to the discretion of the attending physicians. All healthcare providers involved were blinded to the biomarkers results.

Sampling and measurement of the [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index

Urine samples for biomarker analysis were collected twice: at ICU admission and up to 12 h later simultaneously with the morning blood work. Urine samples were centrifuged, and supernatants were frozen at ≤−70 °C and stored until analysed. Before analysis in a central laboratory at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, aliquots were thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min. A previous study in the central laboratory showed there were no significant differences in the [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index between fresh and frozen urine samples (data not shown). The [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index was measured by a sandwich fluorescent quantitative immunoassay adapted to a portable device (Nephrocheck®, Astute Medical). All samples were analysed in the same batch to avoid between-batch variability. The portable device provides a [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index in ((ng/mL)2/1000) units. According to the manufacturer, an index ≤0.3 suggests a low risk of AKI, values between 0.3 and 2.0 suggest a high risk, and values >2.0 suggest a very high risk [15].

Data collection

Clinical data included patient demographics and comorbidities. The APACHE II score, the SAPS II and the SOFA score were recorded at ICU admission. Patients were classified following the AKIN classification [11], which includes changes in sCr and urine output. Baseline sCr was taken from patients’ pre-admission records whenever possible and used to estimate eGFR before ICU admission using the Cockcroft–Gault formula. When baseline sCr was not available, AKI was defined only with AKIN urine output criterion. Sepsis and septic shock were defined according to standard criteria [1, 21].

Statistical analysis

IBM® SPSS® version 21 (IBM corp., Armonk, NY) was used. Variables with Gaussian distribution are reported as mean ± standard deviation and were compared with the Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance. Variables with a non-Gaussian distribution are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared with Mann–Whitney’s U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical data are reported as percentage and were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test.

The primary outcome of the study was AKI prediction with the [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index. For statistical analyses, we used the highest value observed during the first 12 h of ICU admission as the worst index. Reporting of results followed the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) statement. As [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index provides a quantitative result that it is interpreted with two cut-offs, analysis was performed to establish the diagnostic accuracy of the test in comparison with the reference standard, which is the AKIN definition of AKI. Diagnostic values, positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) were assessed a priori for AKI statistically relevant variables by the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUROC) and by the odds ratio (OR). Results were presented with a 95% confidence interval and probability (p). For selected thresholds of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7], sensitivities, specificities, PPV and NPV were reported for the worst [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] value within the first 12 h in the ICU. The ROC analysis was used to calculate the best [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] cut-off point for AKI and AKIN ≥ 2 prediction. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

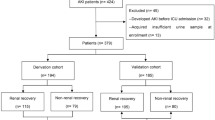

We recruited 100 consecutive patients fulfilling the admission criteria in the ICU of two university hospitals, from June 2011 to April 2013. Two patients were excluded from the study because one of their samples was missing (Fig. 1). Table 1 includes the main characteristics and outcomes of the overall study population as well as in subgroups depending on the occurrence of AKI and sepsis at admission. Further epidemiological data are included in Additional file 1: Table S1.

At admission, 44 patients presented some grade of AKI, more frequently observed in septic patients; 19 fulfilled criteria for AKIN 1, 20 AKIN 2 and 5 AKIN 3. Throughout ICU admission AKI affected 49 of 98 patients. The incidence of AKIN ≥ 2 increased from 25.5 to 31.6% in those patients who presented AKI. Five of 98 patients required RRT within the first 48 h of admission. 40.8% had sepsis at ICU admission.

When comparing subgroups depending on the occurrence of AKI and sepsis in ICU (Table 1; Additional file 1: Table S1), those patients in AKI or sepsis categories were older and had a higher incidence of shock and higher severity scores. Although the incidence of shock in both subgroups was higher, there was no statistical difference in the incidence of septic shock between the non-AKI and AKI subgroups. Septic patients also showed a lower baseline eGFR. However, baseline sCr and the remaining patients’ characteristics for both subgroups did not differ.

Overall mortality was 10.2% in ICU, and 12.2 and 13.3%, respectively, at 28 and 90 days (Table 1; Additional file 1: Table S1).

Composite index of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]

[TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index values were significantly higher in patients with AKI (1.03, IQR 0.38–3.29) than in those without AKI (0.24, IQR 0.11–0.48) (p < 0.001) (Table 1). These differences were unrelated to the presence of sepsis (Table 2). Patients who developed AKI presented higher median index values (1.05, IQR 0.41–2.31 for patients without sepsis; 0.98, IQR 0.36–3.94 for septic patients) than those without AKI (0.21 IQR 0.10–0.40 in non-septic patients and 0.32 IQR 0.15–0.63 for those with sepsis) with p < 0.001 between subgroups with and without AKI (no statistical differences were found between septic and non-septic status).

The index values were significantly related to AKI presence and severity according to AKIN criteria (Fig. 2). In contrast, index values did not appear to be influenced by sepsis, either in AKI or non-AKI patients (Table 2).

Boxplot comparing the worst [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index and sCr upon admittance with the worst AKIN. Boxplots indicate the median, 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers indicate the 5th and 95th percentiles. Statistical significance (p) comparing each biomarker index with AKIN and RIFLE categories. p was determined by Kruskal–Wallis test, not correlation. We found statistical differences in the worst [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index concentrations when comparing the subgroup without AKI with any degree of AKI defined by AKIN. Between non-AKI and AKIN 1, p was 0.014 and p < 0.001 when comparing with AKIN 2 and AKIN 3. In between AKIN 1 and AKIN 3, p = 0.004, whereas in between AKIN 2 and AKIN 3 p = 0.039. When comparing sCr levels with AKIN, we found differences between the subgroup without AKI with AKIN 1 (p = 0.008), AKIN 2 and 3 (for both p < 0.001). In between AKIN 1 and 3, p was 0.048 and p = 0.033 in AKIN 2 versus AKIN 3

[TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] values increased in 44% of patients within 12 h of ICU admission; index values decreased in all other patients. Overall, a repeated determination of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] did not show any differences between non-AKI/AKI and non-septic/septic subgroups (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

We divided the patients into 3 subgroups depending on the cut-offs proposed in previous studies [15] (Table 3). Although baseline sCr showed no statistically significant difference between subgroups, baseline eGFR significantly declined at index values >2.0. AKI occurrence and AKIN ≥ 2 during ICU stay were significantly more frequent in the groups with index >0.31. However, the need for RRT did not differ according to the index values. There were also differences between subgroups in the incidence of shock, SAPS II score and ICU length of stay. Patients with high-risk values also had longer ICU length of stay but not hospital length of stay, both with wide standard deviation. According to the manufacturer’s [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] stratification, both subgroups of patients with high and very high-risk values needed RRT. There were no differences between subgroups regarding ICU mortality or mortality at 28 and 90 days.

We assessed the best predictive cut-off of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index to predict AKI and AKIN ≥ 2.0 in our population. Table 4 details the sensitivity and specificity of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] test with increasing indexes, as well as the overall accuracy of the test to predict AKI and AKIN ≥ 2. The AUROC curve of the worst value [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] within the first 12 h of ICU admission for AKI prediction was 0.798 (0.709–0.886, p < 0.0001)) for an index value of 0.40, with sensitivity of 73.5% (95% CI 69.7–77.5%) and specificity of 71.4% (95% CI 67.4–75.4%) (Table 4; Fig. 3). To predict AKIN ≥ 2, the AUROC was 0.805 (0.700–0.909, p < 0.0001) with an index value of 0.80, sensitivity of 72.0% (95% CI 68.1–75.9%) and specificity of 78.1% (95% CI 74.6–81.8%).

Patients with index values ≥0.80 (ng/mL)2/1000 were older (Table 3). Our threshold did not reveal differences in baseline sCr, baseline eGFR, ICU or hospital length of stay between subgroups. The incidence of shock was higher in patients with index values ≥0.8, although this difference was only marginally significant (p = 0.053). However, all patients requiring RRT showed an index value ≥0.8. Thus, compared with the values previously reported in other studies, the observed cut-offs identified 25 additional patients that would not require RRT.

We also evaluated PPV and NPV for both sets of cut-offs (data not shown). However, both sets were equally able to differentiate patients with AKI and AKIN ≥ 2. Although the low incidence of RRT per se increases the NPV, our own specific cut-offs better classified those patients who finally underwent RRT (p = 0.007), with a NPV of 100% (95% CI 96.4–100%) for a cut-off >0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000) versus 96.2% (95% CI 92–100%) for a cut-off >2 ((ng/mL)2/1000). Values above 2 ((ng/mL)2/1000) could only rule out the need of RRT in 40% of cases (95% CI 0–83%).

Taking into account the characteristics of our population (Tables 1, 3), we conducted stepwise logistic regression analysis using as covariates age, sepsis, shock, previous hepatopathy, secondary ARDS, SAPS II, SOFA at admission and the worst value [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] for AKI and AKIN ≥ 2 prediction. In our equation, [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index showed an OR of 3.15 (95% IC 1.60–6.17, p = 0.001) for AKI prediction and 1.85 (95% IC 1.33–2.57, p = 0.001) for AKIN ≥ 2 prediction.

Discussion

Our results showed that the [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index is a useful predictor of AKI in the first 12 h of ICU admission in both septic and non-septic critically ill patients otherwise free of common AKI risk factors. Our AUROC curves of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] for prediction of both AKI and AKIN ≥ 2 (0.798 and 0.805, respectively) agreed with the results already described in the literature [15, 22,23,24,25]. A recently published subgroup analysis of septic patients in sapphire and topaz studies shows similar results [26]. In our study, patients with high index values showed a 3.15- and a 1.85-fold risk to present AKI and AKIN ≥ 2, respectively. The most relevant finding in our study is that a cut-off [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] of 0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000) showed a NPV 100% for RRT requirement. Thus, beyond their AKI prognostic capacity, these biomarkers also ruled out the need for RRT below this threshold over the first 12 h of ICU admission.

Sepsis is a common feature in ICU patients [1]. In our study, 40.8% of patients were septic at ICU admission and had a higher incidence of AKIN ≥ 2. Gómez’s unified theory of sepsis-induced AKI may explain why some critically ill patients can present AKI in hyperdynamic and/or non-hypotensive status [27]. AKI and sepsis are reciprocal risk factors. Sepsis triggers inflammation and oxidative stress, and promotes microvascular dysfunction, which can lead to AKI. On the other hand, AKI impairs monocyte cytokine production and elevates plasma cytokine levels [28], acting as a sepsis risk factor. The fact that [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] are independently associated with AKI in sepsis is a relevant advantage of these biomarkers compared with more widely described NGAL or cystatin-C [29,30,31].

Another important finding regards the timing to analyse [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]. Repeated determinations of any biomarker in a short period of time may reduce their intrinsic variability and increase their diagnostic or prognostic power. We performed two [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] determinations (admission and up to 12 h later) for each patient. In a post-operative cardiac surgery setting, Meersch [23, 32] showed that [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] rose as fast as 4 h after surgery (AUROC 0.84, Se 0.92 Sp 0.81) for the highest concentration of [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] within the first 24 h. However, in our study, repeated determinations did not improve prediction. This is relevant because a single analysis is easier to implement and decreases costs. The manufacturer recommends repeat testing of patients with an inconclusive result. We would only suggest considering repeating the test in those cases in which clinically their result is difficult to interpret.

Our study tested these biomarkers in a selected ICU population free of common AKI risk factors [33]. Most studies analysing the role of classical or emerging biomarkers in ICU subjects have been done in unselected populations. Accordingly, the number of patients presenting different degrees of renal dysfunction is variable, but usually high. AKI is a common complication of many non-renal hospitalisations [34, 35]; it has been estimated that the incidence of hospital-acquired renal insufficiency is about 7% [36]. Ideally, to describe the characteristics of a new AKI biomarker this incidence should be studied in subjects with a normal baseline renal function. Although our patients may not fully represent an average ICU population in view of our selective inclusion and exclusion criteria, our approach decreases the confounding effect of intra-hospital risk factors to develop AKI, such as exposure to nephrotoxics, hypotension and nosocomial sepsis.

Patients with AKI and/or sepsis showed higher severity scores, and ICU and hospital length of stay, although the latter did not reach statistical difference. Mortality rates remained very low. Thus, we did not find significant differences. This could be partially explained because of our study exclusion criteria. We excluded patients with established anuric AKI at admission, who had the highest risk for poor outcome related to AKI [2, 3], and patients with an expected ICU length of stay <2 days because of their severe condition. Besides, we did not recruit those subjects who had already been hospitalised. In a subanalysis of the PICARD study [37], which analysed the relationship between AKI and sepsis, septic patients either before or after AKI onset presented higher mortality rates than non-septic patients (48, 44 and 21%, respectively).

We also clinically assessed the cut-off values described in the literature. The sapphire and opal studies [15, 16] reported the same cut-off values for the risk of AKI development. In our cohort, the best cut-off index values were 0.4 and 0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000) to differentiate no AKI risk, high risk and very high risk (Table 4). The lower cut-off was very close to the 0.3 previously reported, and it is in keeping with the value cited in the FDA report [38]. Thus, the lower threshold may be helpful to consider before the indication of procedures involving nephrotoxics or to avoid starting RRT in oliguric patients. We also found a consistent NPV above 70% to exclude any degree of AKI. When using our own threshold for very high risk of AKI [0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000)], we did differentiate all patients who finally underwent RRT (p = 0.007). The controversy arises in the 0.41–0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000) range; although this subgroup of patients might benefit from a second sampling, this is not supported by our results.

The main limitations in our study are the small sample size and the enrolment in only two centres. Although the overall findings are consistent with recent studies, our thresholds do need further validation. The main strength of the study is the clinical design. The restricted inclusion criteria reduced the size of our cohort and the statistical power, which may also explain the low mortality rate. However, we obtained most baseline sCr and we ensured that patients who developed AKI did not have previous significant CKD. Unlike most observational studies, our proof of model selection of patients also ruled out the added effect of intra-hospital risk factors for AKI.

Conclusions

Unlike other renal biomarkers, [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] predict AKI in both septic and non-septic critically ill patients. These biomarkers are especially useful to promptly differentiate patients without AKI from those with a very high risk of developing AKI. Below the cut-off value of 0.8 ((ng/mL)2/1000), the [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index was able to exclude those patients who needed RRT in our study population.

Abbreviations

- TIMP-2:

-

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2

- IGFBP7:

-

insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

acute kidney injury network definition

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy

- sCr:

-

serum creatinine

- RIFLE:

-

risk–injury–failure–loss–end-stage renal disease classification

- ED:

-

emergency department

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- CrCL:

-

creatinine clearance

- APACHE II:

-

acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SOFA:

-

sequential organ failure assessment

- SIRS:

-

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- Md:

-

median

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- PPV:

-

positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

negative predictive value

- AUROC:

-

area under the receiver operator characteristic curve

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- Se:

-

sensitivity

- Sp:

-

specificity

References

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–6.

Hoste EAJ, Schurgers M. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury: how big is the problem? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4 Suppl):S146–51.

Metnitz PGH, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051–8.

Oppert M, Engel C, Brunkhorst F-M, Bogatsch H, Reinhart K, Frei U, et al. Acute renal failure in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock—a significant independent risk factor for mortality: results from the German Prevalence Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):904–9.

Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, et al. Septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(11):431–9.

Lopes JA, Jorge S, Resina C, Santos C, Pereira A, Neves J, et al. Acute renal failure in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2007;11:411.

Bagshaw SM, Lapinsky S, Dial S, Arabi Y, Dodek P, Wood G, et al. Acute kidney injury in septic shock: clinical outcomes and impact of duration of hypotension prior to initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:871–81.

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients a multinational, multicenter study. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(7):813–8.

Gomez H, Ince C, De Backer D, Pickkers P, Payen D, Hotchkiss J. A unified theory of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: inflammation, microcirculatory dysfunction, bioenergetics, and the tubular cell adaptation to injury. Shock. 2014;41:3–11.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure–definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8(4):R204–12.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31.

Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, Barsoum RS, Burdmann EA, KDIGO Group, et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138.

Dunn B, Anderson S, Brenner B. The hemodynamic basis of progressive renal disease. Semin Nephrol. 1986;6(2):122–38.

Brenner B, Rector F. The kidney. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000.

Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T, Artigas A, Bagshaw SM, Bell M, et al. Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care BioMed Central Ltd. 2013;17(1):R25.

Hoste EAJ, McCullough PA, Kashani K, Chawla LS, Joannidis M, Shaw AD, et al. Derivation and validation of cutoffs for clinical use of cell cycle arrest biomarkers. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(11):2054–61.

Rifai N, Gillette MA, Carr SA. Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(8):971–83.

Seo D-W, Li H, Qu C-K, Oh J, Kim Y-S, Diaz T, et al. Shp-1 mediates the antiproliferative activity of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in human microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(6):3711–21.

Bonventre J, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(11):4210–21.

Witzgall R, Brown D, Schwarz C, Bonventre JV. Localization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, vimentin, c-Fos, and clusterin in the postischemic kidney. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(May):2175–88.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Ari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definition for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(8):801–10.

Yamashita T, Doi K, Hamasaki Y, Matsubara T, Ishii T, Yahagi N, et al. Evaluation of urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in acute kidney injury: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):1–9.

Meersch M, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Martens S, Rossaint J, Singbartl K, et al. Urinary TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 as early biomarkers of acute kidney injury and renal recovery following cardiac surgery. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e93460.

Bihorac A, Chawla LS, Shaw AD, Al-Khafaji A, Davison DL, DeMuth GE, et al. Validation of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers for acute kidney injury using clinical adjudication. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(8):932–9.

Gocze I, Koch M, Renner P, Zeman F, Graf BM, Dahlke MH, et al. Urinary biomarkers TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 early predict acute kidney injury after major surgery. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0120863.

Honore PM, Nguyen HB, Gong M, Chawla LS, Bagshaw SM, Artigas A, et al. Urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 for risk stratification of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):1851–60. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001827.

Gomez H, Ince C, De Backer D, Pickkers P, Payen D, Hotchkiss J, et al. A unified theory of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: inflammation, microcirculatory dysfunction, bioenergetics, and the tubular cell adaptation to injury. Shock. 2014;41(1):3–11.

Himmelfarb J, Le P, Klenzak J, Freedman S, McMenamin ME, Ikizler TA. Impaired monocyte cytokine production in critically ill patients with acute reanl failure. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2354–60.

Mårtensson J, Bell M, Oldner A, Xu S, Venge P, Martling C-R, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocaline in adult septic patients with and without acute kidney injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(8):1333–40.

Wheeler DS, Devarajan P, Ma Q, Harmon K, Monaco M, Cvijanovich N, et al. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1297–303.

Bagshaw SM, Bennett M, Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Egi M, Morimatsu H, et al. Plasma and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in septic versus non-septic acute kidney injury in critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(3):452–61.

Stege D, Meersch M, Schmidt C, Aken H Van, Rossaint J, Go D, et al. Validation of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers for acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110865. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110865.

Bienholz A, Wilde B, Kribben A. From the nephrologist’s point of view: diversity of causes and clinical features of acute kidney injury. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(4):405–14.

Hou S, Bushinsky D, Wish J, Cohen J, Harrington J. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am J Med. 1983;74(2):243–8.

Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(4):349–55.

Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):930–6.

Mehta RL, Bouchard J, Soroko SB, Ikizler TA, Paganini EP, Chertow GM, et al. Sepsis as a cause and consequence of acute kidney injury: program to improve care in acute renal disease. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(2):241–8.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2014). Evaluation of automatic class III designation for nephrocheck test system. Retrieved from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/DEN130031.pdf.

Authors’ contributions

MC, JO-Ll and AJB had full access to all data in the study. They take responsibility for both the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. Both authors JO-Ll and AJB were equally directors of the work. MC, JO-Ll, AJB, JB, JS and XP enrolled subjects and collected data from the two ICU involved in the study. All authors reviewed the data and participated in discussions related to interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study sponsor (LaboratorisRubió) was responsible for providing the portable device (Nephrocheck®, Astute Medical). The study design, data analysis and interpretation were independently performed by MC, JO-Ll and AJB. Carolyn Newey made the grammar review. The authors would like to thank the staff in the ICU and biochemistry departments who generously participated in sample processing and analysis and whose work is essential to the completion of this study.

Competing interests

MC has received congress fees from Laboratoris Rubió to present the preliminary results of this study at ISICEM 2015.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the study findings can be shared upon direct request to the authors in a collaborative research approach.

Consent to participate

We obtained informed consent from patients or their guardians.

Consent for publication

The article manuscript does not contain any individual persona data.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (CEIC, Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica) at each participating centre. CEIC Codes: Código Lab IIBSP-NPC-2011-84, EUDRA CT: not applicable, Ref HSCSP: 11/105(OBS).

Funding

The study did not have any funding support.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

13613_2017_317_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1. Main characteristics of study population in subgroups of AKI/non-AKI and septic/non-septic patients. Values expressed as either % per column or mean ± standard deviation; NS no statistical significance; p value of significance. Abbreviations in alphabetical order. AKI acute kidney injury, AKIN acute kidney injury definition, APACHE II acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, BMI body mass index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM diabetes mellitus, HTN hypertension, RRT renal replacement technique, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment score. *Exposure to either nephrotoxic or diuretic prior to ICU admission. **Differences in medical admission are due to higher incidence of neurological admissions in subgroup of non-septic patients (24.1% in non-septic subgroup vs. 7.5% in septic patients) and higher incidence of respiratory admissions in septic patients (10.3% in non-septic vs. 47.5% in septic subgroup). As shown in the table, none of the trauma patients included presented concomitant sepsis at ICU admission.

13613_2017_317_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Boxplot for [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] index values at each determination and depending on AKI and sepsis occurrence. Boxplot represents index values upon admission and up to 12 h later for the overall study population as well as for the subgroups of patients with and without sepsis upon ICU admission. BM biomarker, NS no statistical significance.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuartero, M., Ballús, J., Sabater, J. et al. Cell-cycle arrest biomarkers in urine to predict acute kidney injury in septic and non-septic critically ill patients. Ann. Intensive Care 7, 92 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0317-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0317-y