Abstract

Background

The benefit of ICU admission for elderly patients remains controversial. This report highlights the methodology, the feasibility of and the ethical and logistical constraints in designing and conducting a cluster-randomized trial of intensive care unit (ICU) admission for critically ill elderly patients.

Methods

We designed an interventional open-label cluster-randomized controlled trial in 24 centres in France. Clusters were healthcare centres with at least one emergency department (ED) and one ICU. Healthcare centres were randomly assigned either to recommend a systematic ICU admission (intervention group) or to follow standard practices regarding ICU admission (control group). Clusters were stratified by the number of ED annual visits (<44,616 or >44,616 visits), the presence or absence of a geriatric ward and the geographical area (Paris area vs other regions in France). All elderly patients (≥75 years of age) who got to the ED were assessed for eligibility. Patients were included if they had one of the pre-established critical conditions, a preserved functional status as assessed by an ADL scale ≥4 (0 = very dependent, 6 = independent), a preserved nutritional status (subjectively assessed by physicians) and without active cancer. Exclusion criteria were an ED stay >24 h, a secondary referral to the ED and refusal to participate. The primary outcome was the mortality at 6 months calculated at the individual patient level. Secondary outcomes were ICU and hospital mortality, as well as ADL scale and quality of life (as assessed by the SF-12 Health Survey) at 6 months.

Results

Between January 2012 and April 2015, 3036 patients were included in the trial, 1518 patients in 11 clusters allocated to intervention group and 1518 patients in 13 clusters allocated to standard care. There were 51 protocol violations.

Conclusions

The ICE-CUB 2 trial was deemed feasible and ethically acceptable. The ICE-CUB 2 trial will be the first cluster-randomized trial to assess the benefits of ICU admission for selected elderly patients on long-term mortality.

Trial registration Clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT01508819

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ageing of the population leads to an increase in intensive care unit (ICU) admissions among elderly patients [1], and patients over 80 years represent 10–20 % of all ICU admissions in Western countries [2–5]. Elderly patients are more vulnerable to acute stress due to age-related diminution of physiological reserve and more common frailty than younger patients [6]. This vulnerability of elderly patients to acute stress makes the benefit of an ICU admission uncertain. Because a judicious resources use is a source of concern in the ICU [7], only patients who would benefit from an ICU stay should be admitted [8]. However, there are no clear recommendations to help physicians in the ICU admission decision-making process for elderly patients [9]. The absence of recommendations leads to an heterogeneity in clinical practices within the same region and across different countries [10, 11].

Until now, there is no randomized clinical trial of ICU admission for elderly patients in the literature. Moreover, epidemiological and observational studies [2, 5, 9, 10, 12–16] failed to provide clear evidence of benefit. In a prospective, observational, cohort study (ICE-CUB 1 study, n = 2646 patients) [10], ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients did not affect the mortality at 6 months (50.6 % for patients admitted to the ICU compared to 50.7 % for all other elderly patients) [10, 17–19]. However, preserved functional status, preserved nutritional status and absence of cancer were associated with a better prognosis at 6 months (62 % mortality for patients without any of these factors versus 31 % mortality for patients with at least one) [10].

Past studies demonstrated a great variation in ICU admission rates for elderly patients, ranging from 8 to 40 % [4, 10, 12–14, 20]. This variability is in part due to differences in medical practices regarding ICU admission, differences in local policies and variability of ICU beds availability. The interpretation of these studies is limited by the absence of consideration of the triage process by the ED physicians prior to the ICU admission. If ED physicians are very selective for ICU candidates, this will result in ICU admission requests for highly selected patients only, then a low refusal rate by intensive care physicians. On the other hand, a more liberal process for ICU admission will result in a higher refusal rate by intensive care physicians. In the ICE-CUB 1 study, only 25 % of patients with a critical condition were referred to the ICU by the ED physicians [10]. Independent factors associated with the absence of ICU referral by the ED physicians were a high age, an active cancer, a low severity of the acute illness and a low score on Activities of Daily Living scale (ADL scale) [11]. Therefore, to better understand the ICU admission decision-making process for the elderly patients, there is a need to evaluate both the ED and ICU physician triage processes.

This report highlights the methodology, the feasibility of and the logistical and ethical constraints in designing and conducting a study to assess the benefit of ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients (the ICE-CUB 2 study).

Methods

Objective and design

We aimed at designing a feasible, ethically acceptable, generalizable and reproducible trial with relevant outcomes. Since randomization of ICU admission at individual patient level is considered unethical (by virtue of beneficence, non-maleficence and respect of the patient’s autonomy), we designed an interventional open-label cluster-randomized trial. Our primary research question was whether a recommendation for a systematic ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients who got to the ED can improve survival at 6 months, compared to usual care.

Participating hospitals

To maximize the generalizability of the results, the ICE-CUB 2 study aimed to involve a geographically and clinically diverse spectrum of EDs and ICUs across France. Clusters were academic or non-academic healthcare centres with at least one ED and one ICU willing to participate.

Patients

In each participating hospital, all elderly patients (>75 years of age) who got to the ED were assessed for eligibility. Patients were included in the trial if they met all the inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

A diagnosis among a pre-established list of critical conditions (Table 1).

Table 1 Main admission criteria -

2.

A preserved functional status, as assessed by an ADL scale [21] ≥4 (0 = very dependent, 6 = independent).

-

3.

A preserved nutritional status (defined as the absence of cachexia).

-

4.

No known active cancer.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

An emergency department stay >24 h.

-

2.

A secondary referral to the emergency department.

-

3.

Patient’s or surrogate decision-makers’ refusal to participate.

-

4.

No social security coverage.

The list of critical conditions that required ICU admission was retrieved from the ICE-CUB 1 study [11]. This list of critical conditions adapted to the elderly patient was established by a Delphi consensus method among emergency physicians and adapted from the Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage [22]. We also restricted the list mostly to critical conditions that potentially require an organ support (Table 1). In order to focus on patients perceived as good candidates for ICU admission, we excluded patients with factors of poor prognosis, as identified in the ICE-CUB 1 study: presence of cachexia, active cancer and a decline in functional status [10]. We used the ADL scale [21] to evaluate the functional status, since this scale is widely employed and easy to use. We subjectively assessed the nutritional status by physician at bedside because it is faster and easier compared to a BMI calculation in an emergency room setting and because nutritional laboratory assessments are not reliable in critically ill patients [23].

Randomization

The allocation schedule was independently established by a statistician (AB) at the clinical research unit using a computer-generated randomization list. Randomization was stratified by the annual number of ED visits (the cut-off value was the median of the annual number of ED visits in each participating centres, N = 44,616) and the presence or absence of a geriatric ward and the geographical area (Paris area vs other regions in France). The allocation was kept concealed by the clinical research unit until the beginning of the study. The investigators, physicians and patients were not blinded due to the study design.

Intervention

In the intervention group, ED and intensive care physicians were asked to recommend a systematic ICU admission for all included patients. In case of unavailability of an ICU bed, another ICU bed had to be found in another or other hospital. In that case, patient’s transfer was done in priority in wards or centres participating in the study. If no ICU bed was available in participating wards/centres, patients could be transferred in a ward/centre not participating in the study. In these patients, the case report forms were completed as appropriate. All patients had to undergo a bedside evaluation by the intensive care attending physicians. The clinical case of all patients had to be systematically discussed between the ED and intensive care attending physicians. At the beginning of the trial, in-hospital meetings were organized with members of the scientific committee, ED and ICU staff to introduce and explain the trial. During the study period, there were monthly visits by clinical research nurses and ICU admission rates were presented during a twice-yearly investigators’ meetings and through newsletters.

In the control group, ED and intensive care physicians did not receive any recommendation regarding ICU admission (usual care). For all included patients (intervention and control groups), the final decision for ICU admission was made by the clinician at bedside and/or the patient or their surrogate decision-makers.

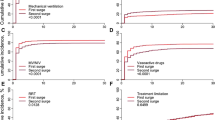

Data collection

Screening forms of eligibility criteria were available at the emergency department of each participating hospital. A case report form (CRF) was filled out for each included patient by the ED and intensive care attending physicians. We collected the following data: age; sex; demographic and social characteristics; living place; clinical and biological evaluations to estimate the SAPS3 [24] (in the ED, one hour before admission to ICU or to another ward); prior comorbidities; ADL scale [21]; circumstances of the ED visit (day, time, availability of an ICU bed); referring physician; ED and intensive care physicians’ characteristics (age, gender, years of experience); physicians’ requests for an ICU admission; patient’s and family’s wishes about ICU admission; circumstances of the decision about ICU admission; final triage decision; characteristics of the hospital stay (admission and discharge dates and locations); survival status at ICU and hospital discharge. For patients admitted to the ICU, we collected performed invasive procedures, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs administration, massive fluid resuscitation (defined as greater than half of an estimated body blood volume) and renal replacement therapy.

Follow-up

Follow-up at 6 months was performed through phone calls or written questionnaires. If the patient could not be reached, relatives and/or the general practitioner was contacted. When necessary, the vital status was retrieved from appropriate legal institutions.

Conduct of the study

The clinical research unit facilitated the conduct of the trial through an effective logistical coordination:

-

Study nurses helped gathering missing information from CRFs and made follow-up phone calls;

-

Clinical research assistants were responsible for centres set-up, monthly visits to intervention centres, completeness audit, database management and centres closures.

-

Weekly control visits were organized in centres with low recruitment rates.

Outcome measures

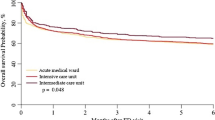

The primary outcome was the overall mortality at 6 months (individual level outcome).

Secondary outcomes were:

-

ICU admission rate,

-

ICU mortality,

-

Hospital mortality,

-

Functional status at 6 months (as assessed by the ADL scale [21]),

-

Quality of life at 6 months (as assessed by the SF-12 Health Survey [25]).

A substudy of caregivers’ burden of care with only two centres is also planned. The evaluation of the burden of care was performed using the Zarit Burden Interview [26].

Sample size and statistical analysis plan

Sample size

Using data from the ICE-CUB 1 study, we estimated a 32 % 6-month mortality rate in the control group. Considering an estimated intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.01, we estimated that 3000 patients would provide a power of 74 % to detect a difference of 6 % in mortality rates between the two groups, with a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05. We planned to recruit 25 centres during an inclusion period of 2 years and a half, based on a predicted average of 56 included patients per year per centre (data from ICE-CUB 1 study).

Statistical analysis plan

We will perform an intention-to-treat analysis using multilevel and mixed models. Specifically, random effect models will be used to take into account the clustered nature of the data. Multilevel logistic models with robust variance will be used for binary outcome variables and mixed effect Cox model for survival data. We planned a subgroup analysis on patients admitted in the ICU and with at least one organ support (mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy or vasopressors). R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) will be used for statistical analyses. No interim analysis is planned.

Quality of the data

The quality of the data was assessed by an independent clinical research assistant through data monitoring online. Systematic tests for consistency of the data were performed. Five per cent of the CRFs were randomly analysed. If discrepancies were >5 % in a centre, all data registered for that centre were verified.

Ethical considerations and legal requirements

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France), and all responsible authorities from each centres provided consent. Patient’s or surrogate decision-makers’ non-opposition to trial participation was assessed. An information sheet with contact details was handed to all patients and/or surrogate decision-makers. The authorization to use the patient’s data could be withdrawn by the patient or the surrogate decision-makers at any time.

The nominative database was approved by CCTIRS and CNIL (reference # 911503). The study was registered on Clinical trials.gov (NCT01508819). The electronic case report form (eCRF) was developed by URC-Ouest (TS) and URC-Est (SA), Paris, using online system CleanWeb (http://www.tentelemed.com/en/cleanweb/).

The scientific committee was composed of scientists and physicians from different specialties and backgrounds: intensive care medicine (BG, MG), emergency medicine (DP), geriatric medicine (CT), statistics (AB) and research unit of the hospital (TS).

Funding

The study was funded by the French ministry of health (PHRC 2010 AOM 10154 K100103). The funding source had no interference with the conduct of the study. The research sponsor was the DRCD Ile-de-France who served as an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) (Project Code: K100103/No. IDRCB 2011-A00758-33). The DSMB had full access to the mortality data and could stop the trial in case of important disparity in mortality between groups. None of the members of the scientific committee nor the investigators declared any conflict of interest related to this study.

Results

Twenty-five healthcare centres were randomized to the intervention or the control group (Figs. 1, 2). One centre withdrew consent to participate after the randomization, leaving 24 centres participating to the study. Eleven centres were allocated to intervention group, and 13 centres were allocated to standard care. There were 18 academic centres and 6 non-academic centres. Fifteen centres were located in the Paris area and 9 in other areas in France. Between January 2012 and April 2015, 3036 patients were included in the trial (1518 patients in the intervention group and 1518 patients in the control group). One patient withdrew consent. There were 51 protocol violations for 49 patients (Table 2). Missing values were rare (Table 3). The ADL scale was completed for 83 % of patients.

Discussion

This cluster-randomized clinical trial will assess the benefit of a strategy of recommendation for systematic ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients who get to the emergency department. Our trial was successfully completed and could overcome methodological, ethical and practical issues. Recruitment period lasted 36 months instead of the planned 30 months due to a lower than expected recruitment rate. There were few missing data.

Several constraints made this trial difficult to design and implement. First, despite the clinical equipoise about ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients [10, 18], randomization at the individual patient level was deemed unethical by virtue of beneficence, non-maleficence and respect of the patient’s autonomy. To overcome this barrier, we designed a cluster-randomized trial of a strategy of recommendation for systematic ICU admission for critically ill elderly patients. As the control group was assigned to standard practices regarding ICU admission, patients were not exposed to additional risks than usual. Second, a refusal of ICU admission for elderly patients may consist in a limitation of life-sustaining therapy and refers to an end-of-life decision-making process. The cluster design facilitated the feasibility of the study, as no treatment limitation was imposed to any patient in the course of the study. Furthermore, the final decision for ICU admission was made by the clinician at bedside and/or the patient or their surrogate decision-makers. Third, recruitment period lasted longer than expected due to a lower recruitment rate. Several actions had to be implemented to keep the hospital staff motivated owing to a longer than expected recruitment period. Fourth, elderly patients may have several disabilities (deafness, memory and cognitive impairment, comprehension difficulties) which complicated the follow-up. Finally, the study relied on a shared-decision model between the ED and the intensive care physicians in the intervention arm. We had to make efforts to foster the implication of both ED and ICU teams during the implementation of the study (Additional file 1).

Conclusion

The ICE-CUB 2 trial was deemed feasible and ethically acceptable. This study will be the first cluster-randomized clinical trial to assess the benefit on long-term outcomes of a recommendation for systematic ICU admission for selected critically ill elderly patients.

References

Ageing and health—an agenda half completed. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1509. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00521-8.

Andersen FH, Kvåle R. Do elderly intensive care unit patients receive less intensive care treatment and have higher mortality? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:1298–305.

Bagshaw SM, Webb SA, Delaney A, et al. Very old patients admitted to intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a multi-centre cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2009;13(2):R45.

Ihra GC, Lehberger J, Hochrieser H, et al. Development of demographics and outcome of very old critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(4):620–6.

Nielsson MS, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Rasmussen BS, Tønnesen E, Nørgaard M. Mortality in elderly ICU patients: a cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(1):19–26.

Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, et al. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2014;186(2):E95–102.

Rhodes A, Ferdinande P, Flaatten H, Guidet B, Metnitz PG, Moreno RP. The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1647–53.

Nguyen Y-L, Angus DC, Boumendil A, Guidet B. The challenge of admitting the very elderly to intensive care. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(29):9.

Sprung CL, Danis M, Iapichino G, et al. Triage of intensive care patients: identifying agreement and controversy. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1916–24.

Boumendil A, Angus DC, Guitonneau A-L, et al. Variability of intensive care admission decisions for the very elderly. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e34387.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Boumendil A, Pateron D, et al. Selection of intensive care unit admission criteria for patients aged 80 years and over and compliance of emergency and intensive care unit physicians with the selected criteria: an observational, multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2919–28.

Sprung CL, Artigas A, Kesecioglu J, et al. The Eldicus prospective, observational study of triage decision making in European intensive care units. Part II: intensive care benefit for the elderly. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):132–8.

Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, Barnato AE, Rowan KM, Angus DC. Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(9):875–80.

Bagshaw SM, Webb SAR, Delaney A, et al. Very old patients admitted to intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a multi-centre cohort analysis. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2009;13(2):R45.

Boumendil A, Maury E, Reinhard I, Luquel L, Offenstadt G, Guidet B. Prognosis of patients aged 80 years and over admitted in medical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(4):647–54.

Boumendil A, Somme D, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Guidet B. Should elderly patients be admitted to the intensive care unit? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(7):1252–62.

Boumendil A, Latouche A, Guidet B. On the benefit of intensive care for very old patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1116–7.

Guidet B, Hodgson E, Feldman C, et al. The Durban World Congress Ethics Round Table Conference Report: II. Withholding or withdrawing of treatment in elderly patients admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):896–901.

Nathanson BH, Higgins TL, Brennan MJ, Kramer AA, Stark M, Teres D. Do elderly patients fare well in the ICU? Chest. 2011;139(4):825–31.

Evans TW, Nava S, Mata GV, et al. Critical care rationing: international comparisons. Chest. 2011;140(6):1618–24.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of HE INDEX OF ADL: a standardized measure of biological and physiological function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633–638.

McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN). J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40:159–211.

Moreno RP, Metnitz PGH, Almeida E, et al. SAPS 3—from evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1345–55.

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–8.

Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–55.

Authors’ contributions

AB wrote the protocol and carried out the statistical analysis; MW, JPQ, FXR, FM, YY, SD, KT, PR, MCK, CP were among the top 10 recruiters and participated in investigators meetings; MGO, CT, DP were members of the scientific committee; TB coordinated the study; SA set the eCRF; GL drafted the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation and analysis of the data; BG was the principal investigator and contributed to all steps of the study and takes responsibility for all aspects of the ICE-CUB 2 study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by a grant from Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique—PHRC 2010—ministère de la santé. Unité de Recherche Clinique Paris Ile de France Ouest (URCPO); Ph Aegerter; Unité de Recherche Clinique-Est; T Simon; SALHI Sara Nesrine; France Guyot-Rousseau; and all the TEC and ARC involved in the study. All the ED and ICU teams of the participating centres are acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Boumendil, A., Woimant, M., Quenot, JP. et al. Designing and conducting a cluster-randomized trial of ICU admission for the elderly patients: the ICE-CUB 2 study. Ann. Intensive Care 6, 74 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0161-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0161-5