Abstract

Background

To evaluate the ability of the central venous-to-arterial CO2 content and tension differences to arteriovenous oxygen content difference ratios (∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2, respectively), blood lactate concentration, and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) to detect the presence of global anaerobic metabolism through the increase in oxygen consumption (VO2) after an acute increase in oxygen supply (DO2) induced by volume expansion (VO2/DO2 dependence).

Methods

We prospectively studied 98 critically ill mechanically ventilated patients in whom a fluid challenge was decided due to acute circulatory failure related to septic shock. Before and after volume expansion (500 mL of colloid solution), we measured cardiac index, VO2, DO2, ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios, lactate, and ScvO2. Fluid-responders were defined as a ≥15 % increase in cardiac index. Areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) were determined for these variables.

Results

Fifty-one patients were fluid-responders (52 %). DO2 increased significantly (31 ± 12 %) in these patients. An increase in VO2 ≥ 15 % (“VO2-responders”) concurrently occurred in 57 % of the 51 fluid-responders (45 ± 16 %). Compared with VO2-non-responders, VO2-responders were characterized by higher lactate levels and higher ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios. At baseline, lactate predicted a fluid-induced increase in VO2 ≥ 15 % with AUC of 0.745. Baseline ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios predicted an increase of VO2 ≥ 15 % with AUCs of 0.965 and 0.962, respectively. Baseline ScvO2 was not able to predict an increase of VO2 ≥ 15 % (AUC = 0.624).

Conclusions

∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios are more reliable markers of global anaerobic metabolism than lactate. ScvO2 failed to predict the presence of global tissue hypoxia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The aim of volume expansion, during acute circulatory failure, is to increase cardiac index (CI) and oxygen delivery (DO2) and to improve tissue oxygenation. Unrecognizable and untreated global tissue hypoxia is thought to contribute to the development of multiple organ failure or death. The usual indicators of global tissue hypoxia, such as blood lactate and venous oxygen saturation, are misleading. Increased lactate levels in sepsis are traditionally viewed as the result of activation of anaerobic glycolysis pathway due to inadequate oxygen delivery. According to such paradigms, hyperlactatemia signals tissue hypoxia and hypoperfusion [1, 2]. Nevertheless, in septic states, lactate concentration may increase through other mechanisms unrelated to tissue oxygen debt [3, 4]. Therefore, hyperlactatemia does not necessarily reflect anaerobic metabolism secondary to cellular hypoxia.

Measurement of mixed or central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) has been advocated in order to detect global tissue hypoxia [5]. ScvO2 reflects the balance between oxygen consumption and supply. A low ScvO2 represents a high oxygen extraction (OE) in order to maintain oxygen consumption (VO2) in spite of low DO2. However, a low ScvO2 does not necessarily indicate the presence of VO2/DO2 dependency. It is when ScvO2 cannot decrease proportionally to the decline of DO2 to maintain VO2, that cell moves from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, leading to tissue hypoxia [6]. On the other hand, in septic shock, due to impairment of OE, normal/high ScvO2 values can also be observed in the presence of oxygen debt [5, 6]. Therefore, other markers are needed to indicate the presence of anaerobic metabolism in critically ill patients.

Considering the ratio of the venous-to-arterial CO2 tension difference (∆PCO2) over the arterial-to-venous oxygen content difference (∆ContO2) as a surrogate of the respiratory quotient (RQ), it has been suggested that this ratio can be used as a marker of global anaerobic metabolism in critically ill patients [7]. Recently, Monnet et al. [8] found that this ratio, calculated from central venous blood, predicted an increase in VO2 after a fluid-induced increase in DO2 and, thus, can be able to detect the presence of global tissue hypoxia. However, PCO2 is not equivalent to CO2 content, and the PCO2/CO2 content relationship is curvilinear rather than linear and is influenced by many factors such as pH and oxygen saturation (Haldane effect). Although VCO2/VO2 might be better reflected by the venous-to-arterial CO2 content over ∆ContO2 (∆ContCO2/∆ContO2) ratio, there is no report in the literature whether this latter ratio can predict more accurately a situation of anaerobic metabolism than ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio. Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate the ability of ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2, ∆PCO2/∆ContO2, ScvO2, and blood lactate to predict the presence of the activation of global anaerobic metabolism through VO2/DO2 dependence in septic shock patients. The presence of VO2/DO2 dependency phenomenon was characterized by the increase in VO2 after an acute increase in DO2 induced by volume expansion (VE).

Methods

This prospective single-center observational study was conducted in a general adult intensive care unit (ICU) after approval by our local institutional ethics committee (Lens Hospital, France). Informed consent was obtained from each subject’s next of kin.

Patients

We studied mechanically ventilated patients for whom the attending physician decided to perform a VE due to the presence of at least one clinical sign of inadequate tissue perfusion due to septic shock [2]: (a) systolic arterial pressure <90 mmHg, mean arterial pressure <65 mmHg, or the need for vasopressor infusion; (b) skin mottling; (c) lactate level >2 mmo/L; or (d) urinary output <0.5 mL/kg/h for ≥2 h. Septic shock was defined according to international criteria [9]. Patients had also to be monitored by PiCCO device (PiCCO, Pulsion Medical System, Munich, Germany) as part of routine management of persistent signs of tissue hypoperfusion in our ICU. Exclusion criteria were: liver failure as defined by Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, pregnancy, age <18 years old, moribund, and risk of fluid loading-induced pulmonary edema.

Measurements

CI was obtained with the PiCCO monitor by triplicate central venous injections, in either the internal jugular or subclavian vein, of 20 mL of iced 0.9 % saline solution and recorded as the average of the three measurements.

Arterial lactate levels, arterial, and central venous blood gas were measured using the GEM Premier 4000 (Instrumentation Laboratory Co, Paris, France). The central venous blood was obtained from a central venous catheter with the tip confirmed to be in the superior vena cava at the entrance, or in the right atrium by radiograph. The ∆PCO2 was calculated as the difference between the central venous carbon dioxide tension and the arterial carbon dioxide tension. The arterial (CaO2) and central venous (CcvO2) oxygen contents were calculated using the standard formulas (Additional file 1: Supplementary material). The ∆ContO2 (mL) was calculated as CaO2–CcvO2. The DO2 was calculated by using the formula: DO2 (mL/min/m2) = CaO2 × CI × 10. The VO2 was calculated using the following formula: VO2 (mL/m2) = CI × ∆ContO2 × 10. Oxygen extraction was defined as: OE = VO2/DO2.

We also determined the central venous-to-arterial difference in blood CO2 content [∆ContCO2] according to Douglas et al. [10] (Additional file 1: Supplementary material).

Study protocol

At baseline, a first set of measurements was performed, including hemodynamic and tissue oxygenation variables (Additional file 1: Supplementary material), arterial lactate level, ∆PCO2, ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio, and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio. A 500 mL of colloid solution (4 % human serum albumin, Vialebex®; LFB) was infused to the patient over 15 min via a specific venous line. Immediately after VE, a second set of measurement was recorded, including the same hemodynamic and tissue oxygenation variables. Ventilation parameters and doses of norepinephrine, dobutamine, and sedation drugs were kept constant during the VE.

Statistical analysis

According to changes in CI after the 500-mL VE, patients were classified as fluid-responders (≥15 % increase in CI) or fluid-non-responders. Also, in the fluid-responders’ group, patients were separated into two subgroups according to their increase in VO2 (< or ≥15 %) induced by VE [8]. All data are expressed as mean ± SD when they are normally distributed, or as median [25–75 %, interquartile range, (IQR)] when they are non-normally distributed. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Comparisons of values between different groups of patients were made by two-tailed Student’s t test, or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Pairwise comparisons between different study times were assessed using paired Student’s t test or Wilcoxon’s test, as appropriate. Linear correlations were tested by using the Pearson or the Spearman test, as appropriate. To adjust for the regression to the mean phenomenon, the absolute change in variables over time was also analyzed by performing an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the absolute change in variable as dependent variable, the group of patients as a factor, and the baseline value as a covariate.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the ability of tissue oxygenation variables at baseline to predict an increase of VO2 ≥ 15 % after VE in fluid-responders’ group. The areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) were compared using the nonparametric technique described by DeLong et al. [11]. The best cutoff of a ROC curve was chosen with the highest Youden index [12]. Usually, variables are considered of good clinical tool (having good discriminative properties tests) when the inferior limits of the 95 % confidence interval (CI) of their AUC are more than 0.75 [12]. For this purpose, considering a proportion of VO2 responders of 21 % [8], 51 fluid-responder’s patients are required for a power of 90 % and an alpha risk of 0.05. Assuming a proportion of responders close to 50 %, about 102 patients would be necessary. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) and SPSS for Windows release 17.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All reported P values are two-sided.

Results

Patients

Ninety-eight septic shock patients were prospectively included in this study. The main characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The median time between the start of care and enrollment was 1.7 [1.0–2.0] h. The major source of infection was pneumonia (55 %) with ICU mortality rate of 42.8 %.

The whole population

At baseline, there was a significant but weak correlation between lactate and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 (r = 0.33, p = 0.001) and between lactate and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 (r = 0.32, p = 0.001). Furthermore, fluid-induced changes in ∆PCO2/∆ContO2, ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2, and lactate were weakly correlated (r = 0.25, p = 0.01 and r = 0.21, p = 0.04; respectively). We found a good correlation between ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). Fluid-induced changes in ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios were also well related (r = 0.63, p < 0.001).

Effects of volume expansion on hemodynamic variables

VE increased CI by more than 15 % in 51 patients who were “fluid-responders” (52 %; Additional file 2: Table S1). In these patients, VE significantly increased CI by 30 ± 13 %, DO2 by 31 ± 12 %, and VO2 by 25 ± 26 % (Additional file 2: Table S1). Volume expansion induced less than 15 % increase in CI in 47 patients (48 %). In these patients, we observed no significant changes in DO2 and VO2.

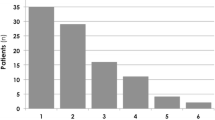

Differences between VO2-responders and VO2-non-responders in fluid-responders’ group

Of the 51 fluid-responders, VE increased VO2 ≥ 15 % (45 ± 16 %) in 29 who were “VO2-responders.” In the remaining 22 fluid-responders, VE did not significantly change VO2 “VO2-non-responders” (Table 2; Fig. 1).

At baseline, compared with the VO2-non-responders, lactate levels and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios were significantly higher in VO2-responders, whereas ScvO2 value was not significantly different between these two subgroups (Table 2). In these patients, ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios decreased significantly by 30 ± 13 and 45 ± 24 % (respectively) with VE, whereas they did not change in VO2-non-responders (Table 2). ScvO2 significantly increased (22 ± 16 %) with VE only in VO2-non-responders (Table 2).

Lactate levels decreased significantly with VE in both VO2-responders and VO2-non-responders. The magnitude of decrease in lactate levels was not different between these two subgroups (13 ± 7 % for VO2-responders vs. 13 ± 10 % for VO2-non-responders, p = 0.98, Table 2).

Among fluid-responder patients, VE-induced changes in ∆PCO2/∆ContO2, ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2, and ScvO2, but not in lactate, were significantly higher, after adjustment to their baseline values, in VO2-responders than in VO2-non-responders (ANCOVA, p < 0.001, p = 0.006, p < 0.001, and p = 0.18; respectively).

VE-induced change in VO2 was not significantly correlated with the changes in lactate (r = −0.17, p = 0.22). However, changes in both ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios induced by VE were well correlated with changes in VO2 (r = −0.52, p < 0.001, and r = −0.59, p < 0.001; respectively).

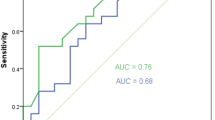

Ability of tissue oxygenation variables to predict the response of VO2 to VE in fluid-responders

The ability of ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 at baseline to predict an increase of VO2 ≥ 15 % induced by VE was excellent in fluid-responder patients with AUCs of 0.962 (95 % CI 0.900–1.000) and 0.965 (95 % CI 0.918–1.000), respectively (Fig. 2). The AUC for baseline value of lactate was 0.745 [(95 % CI 0.608–0.883), p = 0.003 vs. 0.5]. However, ScvO2 at baseline did not predict the VO2 increase of ≥15 % [AUC = 0.624, (95 % CI 0.449–0.798), p = 0.14 vs. 0.5].

AUCs for baseline ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios were both significantly larger than the AUCs for baseline lactate (p = 0.003 and p = 0.002, respectively) and baseline ScvO2 (p < 0.001 for both ratios, Fig. 2). However, there were no significant differences between AUC for ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and AUC for ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 (p = 0.80), neither between AUC for baseline lactate and AUC for baseline ScvO2 (p = 0.24).

The best cutoff values at baseline, when predicting VO2 responsiveness, were ≥1.68 mmHg/mL for ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio [sensitivity = 90 % (95 % CI 71–97 %); specificity = 100 % (95 %CI 81–100 %)], ≥1.02 for ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio [sensitivity = 86 % (95 % CI 67–95 %); specificity = 100 % (95 % CI 81–100 %)], and ≥4.6 mmol/L for lactate [sensitivity = 69 % (95 % CI 49–84 %); specificity = 77 % (95 % CI 54–91 %)] (Table 3). Even though the AUC for baseline ScvO2 was not significantly different from 0.5, a ScvO2 value ≥80 % had a specificity of 100 % (95 % CI 81–100 %) but a sensitivity of 21 % (95 % CI 9–40 %) to predict the VO2 increase ≥15 %. Thus, in fluid-responders, a ScvO2 value ≥80 % was always associated with an increase in VO2 ≥ 15 % induced by VE. Compared with patients with a baseline ScvO2 < 80 %, these patients had higher baseline lactate levels [4.3 (2.3–6.3) mmol/L vs. 7.6 (5.6–8.1) mmol/L, p = 0.011; respectively], higher baseline ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio [1.46 (1.05–2.17) mmHg/mL vs. 2.20 (2.20–2.38) mmHg/mL, p = 0.011; respectively], and higher baseline ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio [0.94 (0.53–1.05) vs. 1.52 (1.42–1.62), p < 0.001; respectively].

Comparisons between patients with ScvO2 > 70 % and patients with ScvO2 ≤ 70 % at baseline in the whole population

Only 28 patients had a ScvO2 of more than 70 % at baseline (Additional file 3: Table S2). They had significantly lower baseline VO2 and higher baseline DO2 compared with patients with low baseline ScvO2. The mean baseline value of VO2 significantly increased with volume expansion only in patients with ScvO2 > 70 % (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Discussion

The main findings of our study were that in fluid-responder septic shock patients (1) the ability of ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratios to predict the presence of global anaerobic metabolism was excellent and higher than lactate; (2) ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio was not a better marker of global anaerobic metabolism than ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio; (3) ScvO2 failed to detect the presence of global tissue hypoxia, except for values ≥80 %.

When DO2 is acutely reduced, VO2 remains stable (oxygen supply independency) because the tissues adapt their OE proportionally. When DO2 falls below a critical low value, a proportionate increase in OE cannot be maintained and the VO2 starts to fall (oxygen supply dependency) and tissue hypoxia occurs as reflected by an abrupt increase in blood lactate concentration [13–15]. Thus, VO2/DO2 dependence has been considered to be a hallmark of tissue hypoxia and the activation of anaerobic metabolism [14–16], although it has been challenged because of the methodological limitations (mathematical coupling) in the VO2/DO2 relationship assessment [17, 18].

We defined an increase in VO2 ≥ 15 % as a clinically significant augmentation by similarity to the definition of the increase in cardiac index, since VO2 is proportional to this variable. This cutoff value was chosen by the fact that the least significant change in CI measured by transpulmonary thermodilution is 11.0 % when 20 mL is used to perform iced saline injections in triplicate (unpublished data). On the other hand, this definition of “VO2 response” allows us comparing our findings with those of a previous study [8]. We confirm the results of Monnet et al. [8] that calculating VO2 from the central instead of the mixed venous blood also allows to detect the presence of anaerobic metabolism through VO2/DO2 dependence. Indeed, in our study, the baseline lactate concentration was elevated in patients with VO2/DO2 dependency phenomenon and higher than in patients with VO2/DO2 independency (Table 2). Moreover, it is hard to believe that mathematical coupling of measurement errors was responsible for the VO2/DO2 dependency in our study. Indeed, we observed that VO2/DO2 dependency occurred in one subgroup of patients but not in others, despite similar changes in DO2 (Table 2). Such a methodological problem can hardly account for the existence of VO2/DO2 dependency only in one subgroup. If that were an issue, one would expect it to influence results uniformly. Finally, the increase in VO2 could have resulted from an additional non-mitochondrial non-oxidative oxygen uptake when dysoxia has resolved [19]. However, this mechanism is less likely to have occurred in our study because the observed mean slope of the VO2/DO2 relationship in the subgroup of VO2-responders was 47.8 ± 10 %, suggesting VO2/DO2 dependency and activation of anaerobic metabolism (Table 2) [20].

In experimental conditions of tissue hypoxia, a smaller reduction in VCO2 than VO2 has been observed, suggesting a non-aerobic production of CO2 [21–23]. Therefore, the occurrence of a high RQ may be considered as a sign of anaerobic metabolism. Recently, Monnet et al. [8] have used the ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio as a surrogate of RQ and found that a ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio at baseline ≥ 1.8 mmHg/mL predicted accurately VO2/DO2 dependence among patients whose DO2 increased after fluid administration. Our results agree with those findings, and interestingly, the observed cutoff value of this ratio, in our septic shock patients, was almost similar to what was found in the Monnet et al. report [8].

The use of ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio as a surrogate of VCO2/VO2 assumes that the PCO2/CO2 content relationship is quasi-linear, which may be true over the physiologic range of PCO2 [24]. However, this relationship can be affected by the degree of metabolic acidosis, hematocrit, and oxygen saturation (Haldane effect), and it becomes nonlinear if these factors change [25]. In this regard, it has been shown that venous-to-arterial PCO2 differences and venous-to-arterial CO2 content differences might change in opposite direction in splanchnic region under conditions of very low venous oxygen saturation [26]. Recently, Ospina-Tascon et al. found a significant association with mortality, in septic shock patients, for the mixed ∆ContCO2/mixed ∆ContO2 ratio but not for the mixed ∆PCO2/mixed ∆ContO2 ratio [27]. Thus, ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio could be a more reliable marker of tissue hypoxia than ∆PCO2/∆ContO2. However, we found that ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 was not better predictor of tissue hypoxia than the ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 in septic shock patients (Fig. 2). It does not seem that Haldane effect has played an important role in our study. Furthermore, the degree of metabolic acidosis, as reflected by base excess, was not severe enough to significantly affect the PCO2/CO2 content relationship in our septic shock patients. Even though the ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratio more physiologically mirrors RQ compared with ∆PCO2/∆ContO2, we found that both ratios can be used accurately to predict fluid responsiveness at tissue level. However, the computation of ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio is less cumbersome and less subject to the risk of errors, and therefore, it is much easier to be used at the bedside.

Lactate value was not good to detect the presence of anaerobic metabolism in our septic shock patients. Our results are in discrepancy with previous findings [7, 8, 28]. However, hyperlactatemia does not necessarily reflect anaerobic metabolism secondary to tissue hypoxia, especially in septic states [3, 4, 29]. Other non-hypoxic mechanisms such as accelerated aerobic glycolysis induced by sepsis-associated inflammation [30], inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase [31], and impaired lactate clearance [32] may contribute to hyperlactatemia found in septic patients. In endotoxic states, lactate levels failed to discriminate between hypoxia and aerobiosis [33]. Furthermore, Rimachi et al. [34] found the presence of hyperlactatemia in 65 % of septic shock patients, but only 76 % of these patients also had a high lactate/pyruvate ratio confirming the non-hypoxic cause of hyperlactatemia in septic states. Moreover, in fluid-responder patients, we found no significant relationship between changes in VO2 induced by VE and changes in lactate levels, whereas changes in ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios were correlated well with changes in VO2. This finding suggests that these ratios respond to changes in global tissue oxygenation faster than blood lactate concentration likely due to the alteration of lactate clearance.

The majority (71 %) of our septic shock patients had a ScvO2 value ≤70 % at their inclusion in the study. This finding is due to the fact that patients, in our study, were recruited in the very early period of acute circulatory failure; the time between the start of care and enrollment was only 102 min. Within this period, septic shock patients are not fully resuscitated yet, and as a consequence, low values of ScvO2 are observed more frequently [35–37]. Even though our population seems to be different from that in the study of Monnet et al. [8], we confirm that ScvO2 is a poor predictor of the presence of anaerobic metabolism. This can be explained by the fact that ScvO2 is not a regulated parameter but an adaptive one that depends on four regulated constituents: oxygen consumption, hemoglobin, SaO2, and cardiac output. Therefore, ScvO2 is widely fluctuating. However, these results should not dissuade us from monitoring ScvO2 but encourage us to include it in a multimodal approach. Indeed, a low ScvO2 value reflects the inadequacy of oxygen supply, and fluid administration can be helpful in order to correct oxygen supply/demand imbalance, even in situations of VO2/DO2 independency, to avoid further decreases in DO2 below a critical value leading to tissue hypoxia. On the other hand, only ScvO2 values ≥80 % were able to predict the presence of global tissue hypoxia with a high specificity. All these patients also had higher lactate levels and higher ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 ratios. This suggests that these patients had a greater alteration of their microcirculation due to sepsis than the other fluid-responder patients. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, since only six patients had a baseline ScvO2 value ≥80 % in fluid-responders’ group, and our study was not designed for testing this hypothesis.

Contrary to what was found previously [8], DO2 did not decrease during VE, in fluid-non-responder patients, even though arterial hemoglobin significantly decreased by 5.6 ± 4.6 % (Additional file 2: Table S1), which was lower than that in the Monnet et al. study (8 ± 4 %) [8]. The discrepancy between the two studies may be due to dissimilar populations of patients and to the differences in the time to inclusion, which was longer in the study by Monnet et al. [8] than that in our study (6.1 vs. 1.7 h) explaining the more pronounced hemodilution effect in their study.

We believe our findings add significant values to the Monnet et al. study [8]. Indeed, we have demonstrated that the ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 ratio is a reliable marker of global anaerobic metabolism in the very early period of septic shock where patients are still not fully resuscitated and that ∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 is not superior to ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 for predicting the presence of global tissue hypoxia in these patients. Furthermore, our study shed the light on the fact that hyperlactatemia should not always be regarded as reflecting the presence of global tissue hypoxia, especially in septic shock patients. This finding is of clinical importance since elevated lactate values could incite the clinician to undertake unnecessary interventions, with their potentially harmful effects, such as tissue edema and positive fluid balance, which have constantly been associated with poorer outcome [38].

Our study presents several limitations. First, we used central venous blood instead of mixed venous to assess VO2- and CO2-derived variables, and thus, we might have missed the evaluation of the splanchnic oxygenation. However, our study is the second one that confirms that calculating oxygen-derived variables from the central venous blood is able to detect the presence of tissue hypoxia through VO2/DO2 dependence. Second, regional or local tissue hypoxia might not be detected by the assessment of the changes in global oxygen consumption. Finally, it is a single-center study, which may limit its external validity.

Conclusion

∆ContCO2/∆ContO2 and ∆PCO2/∆ContO2 are excellent and better markers of global anaerobic metabolism than lactate in fluid-responder septic shock patients. Also, these parameters respond to changes in global oxygenation faster than lactate. ScvO2 cannot predict the presence of global tissue hypoxia, except for values ≥80 %.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

cardiac index

- DO2 :

-

oxygen delivery

- VO2 :

-

oxygen consumption

- ScvO2 :

-

central venous oxygen saturation

- ∆PCO2 :

-

central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide tension difference

- ∆ContCO2 :

-

central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide content difference

- ∆ContO2 :

-

arterial-to-central venous oxygen content difference

- CaO2 :

-

arterial oxygen content

- CcvO2 :

-

central venous oxygen content

- OE:

-

oxygen extraction

- RQ:

-

respiratory quotient

- VE:

-

volume expansion

- AUC:

-

area under receiver operating characteristic curve

- 95 % CI:

-

95 % confidence interval

References

Sterling SA, Puskarich MA, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Kline JA, Summers RL, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with vasoplegic versus tissue dysoxic septic shock. Shock. 2013;40:11–4.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637.

James JH, Luchette FA, McCarter FD, Fischer JE. Lactate is an unreliable indicator of tissue hypoxia in injury or sepsis. Lancet. 1999;354:505–8.

Garcia-Alvarez M, Marik P, Bellomo R. Sepsis-associated hyperlactatemia. Crit Care. 2014;18:503.

van Beest P, Wietasch G, Scheeren T, Spronk P, Kuiper M. Clinical review: use of venous oxygen saturations as a goal—a yet unfinished puzzle. Crit Care. 2011;15:232.

Squara P. Central venous oxygenation: when physiology explains apparent discrepancies. Crit Care. 2014;18:579.

Mekontso-Dessap A, Castelain V, Anguel N, Bahloul M, Schauvliege F, Richard C, et al. Combination of venoarterial PCO2 difference with the arteriovenous O2 content difference to detect anaerobic metabolism in patients. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:272–7.

Monnet X, Julien F, Ait-Hamou N, Lequoy M, Gosset C, Jozwiak M, et al. Lactate and venoarterial carbon dioxide difference/arterial–venous oxygen difference ratio, but not central venous oxygen saturation, predict increase in oxygen consumption in fluid responders. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1412–20.

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:530–8.

Douglas AR, Jones NL, Reed JW. Calculation of whole blood CO2 content. J Appl Physiol. 1998;65:473–7.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45.

Ray P, Le Manach Y, Riou B, Houle TT. Statistical evaluation of a biomarker. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1023–40.

Cain SM, Adams RP. Appearance of excess lactate in anesthetized dogs during anemic and hypoxic hypoxia. Am J Physiol. 1965;209:604–8.

Schumacker PT, Cain SM. The concept of a critical oxygen delivery. Intensive Care Med. 1987;13:223–9.

Vincent JL, Roman A, De Backer D, Kahn RJ. Oxygen uptake/supply dependency: effects of short-term dobutamine infusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1990;142:2–8.

Friedman G, De Backer D, Shahla M, Vincent JL. Oxygen supply dependency can characterize septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:118–23.

Granton JT, Walley KR, Phang PT, Russell JA, Lichtenstein S. Assessment of three methods to reduce the influence of mathematical coupling on oxygen consumption and delivery relationships. Chest. 1998;113:1347–55.

Hanique G, Dugernier T, Laterre PF, Dougnac A, Roeseler J, Reynaert MS. Significance of pathologic oxygen supply dependency in critically ill patients: comparison between measured and calculated methods. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:12–8.

McCord J. Oxygen-derived free radicals in post ischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–61.

De Backer D, Moraine JJ, Berre J, Kahn RJ, Vincent JL. Effects of dobutamine on oxygen consumption in septic patients. Direct versus indirect determinations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:95–100.

Groeneveld AB, Vermeij CG, Thijs LG. Arterial and mixed venous blood acid-base balance during hypoperfusion with incremental positive end-expiratory pressure in the pig. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:576–82.

Cohen IL, Sheikh FM, Perkins RJ, Feustel PJ, Foster ED. Effect of hemorrhagic shock and reperfusion on the respiratory quotient in swine. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:545–52.

Vallet B, Teboul JL, Cain S, Curtis S. Venoarterial CO(2) difference during regional ischemic or hypoxic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1317–21.

Cavaliere F, Giovannini I, Chiarla C, Conti G, Pennisi MA, Montini L, et al. Comparison of two methods to assess blood CO2 equilibration curve in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;146:77–83.

Mchardy GJ. The relationship between the differences in pressure and content of carbon dioxide in arterial and venous blood. Clin Sci. 1967;32:299–309.

Jakob SM, Kosonen P, Ruokonen E, Parviainen I, Takala J. The Haldane effect—an alternative explanation for increasing gastric mucosal PCO2 gradients? Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:740–6.

Ospina-Tascón GA, Umaña M, Bermúdez W, Bautista-Rincón DF, Hernandez G, Bruhn A, et al. Combination of arterial lactate levels and venous–arterial CO2 to arterial–venous O2 content difference ratio as markers of resuscitation in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:796–805.

Mesquida J, Saludes P, Gruartmoner G, Espinal C, Torrents E, Baigorri F, et al. Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide difference combined with arterial-to-venous oxygen content difference is associated with lactate evolution in the hemodynamic resuscitation process in early septic shock. Crit Care. 2015;19:126.

De Backer D. Lactic acidosis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:699–702.

Gore DC, Jahoor F, Hibbert JM, DeMaria EJ. Lactic acidosis during sepsis is related to increased pyruvate production, not deficits in tissue oxygen availability. Ann Surg. 1996;224:97–102.

Vary TC, Siegel JH, Nakatani T, Sato T, Aoyama H. Effect of sepsis on activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in skeletal muscle and liver. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:E634–40.

Levraut J, Ciebiera JP, Chave S, Rabary O, Jambou P, Carles M, et al. Mild hyperlactatemia in stable septic patients is due to impaired lactate clearance rather than overproduction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1021–6.

Curtis SE, Cain SM. Regional and systemic oxygen delivery/uptake relations and lactate flux in hyperdynamic, endotoxin-treated dogs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:348–54.

Rimachi R, Bruzzi de Carvahlo F, Orellano-Jimenez C, Cotton F, Vincent JL, et al. Lactate/pyruvate ratio as a marker of tissue hypoxia in circulatory and septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:427–32.

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–77.

Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, Sleeswijk Visser SJ, van der Klooster JM, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752–61.

Chung KP, Chang HT, Huang YT, Liao CH, Ho CC, Jerng JS, et al. Central venous oxygen saturation under non-protocolized resuscitation is not related to survival in severe sepsis or septic shock. Shock. 2012;38:584–91.

Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada TA, Walley KR, Russell JA. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:259–65.

Authors’ contributions

JM, ML, and MM contributed to the design of the study. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. JM designed and performed the statistical analysis. JM and BV drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nursing staff of the intensive care unit. Without their participations, this work would not have been possible.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

13613_2016_110_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Table S1. Hemodynamic and tissue oxygenation parameters before and after 500 mL of volume expansion in responders and non-responders.

13613_2016_110_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional file 3: Table S2. Hemodynamic and tissue oxygenation parameters before and after 500 mL of volume expansion according to the baseline ScvO2 groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallat, J., Lemyze, M., Meddour, M. et al. Ratios of central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide content or tension to arteriovenous oxygen content are better markers of global anaerobic metabolism than lactate in septic shock patients. Ann. Intensive Care 6, 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0110-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0110-3