Abstract

Background

Evidence for distinct asthma phenotypes and their overlap is becoming increasingly relevant to identify personalized and targeted therapeutic strategies. In this study, we aimed to describe the overlap of five commonly reported asthma phenotypes in US adults with current asthma and assess its association with asthma outcomes.

Methods

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2007–2012 were used (n = 30,442). Adults with current asthma were selected. Asthma phenotypes were: B-Eos-high [if blood eosinophils (B-Eos) ≥ 300/mm3]; FeNO-high (FeNO ≥ 35 ppb); B-Eos&FeNO-low (B-Eos < 150/mm3 and FeNO < 20 ppb); asthma with obesity (AwObesity) (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2); and asthma with concurrent COPD. Data were weighted for the US population and analyses were stratified by age (< 40 and ≥ 40 years old).

Results

Of the 18,619 adults included, 1059 (5.6% [95% CI 5.1–5.9]) had current asthma. A substantial overlap was observed both in subjects aged < 40 years (44%) and ≥ 40 years (54%). The more prevalent specific overlaps in both age groups were AwObesity associated with either B-Eos-high (15 and 12%, respectively) or B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma (13 and 11%, respectively). About 14% of the current asthma patients were “non-classified”. Regardless of phenotype classification, having concomitant phenotypes was significantly associated with (adjusted OR, 95% CI) ≥ 2 controller medications (2.03, 1.16–3.57), and FEV1 < LLN (3.21, 1.74–5.94), adjusted for confounding variables.

Conclusions

A prevalent overlap of commonly reported asthma phenotypes was observed among asthma patients from the general population, with implications for objective asthma outcomes. A broader approach may be required to better characterize asthma patients and prevent poor asthma outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Profiling asthma phenotypes is becoming increasingly relevant to choose the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for individual patients, and to provide optimal improvement of disease control and quality of life [1, 2].

The predominant pathophysiological mechanism of asthma is type 2-mediated, associated with atopy and eosinophilic inflammation [3, 4]. However, it has been shown that asthma is a heterogeneous disease that involves other mechanisms that are not so well understood and respond poorly to corticosteroid therapy (e.g. non-type 2-mediated) [3, 5, 6].

There has been a recent rise in the number of studies that try to identify asthma phenotypes based on non-invasive type 2-markers, such as blood eosinophils (B-Eos) count, fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), serum IgE, and/or serum periostin [7,8,9,10]. Moreover, there appears to be an additive role of biomarkers, such as B-Eos and FeNO, in relation to recent asthma morbidity [7, 11, 12].

However, there is little information regarding the appropriate use of these biomarkers in asthma phenotype classification, particularly when a significant overlap occurs. Also, the importance of having concomitant asthma phenotypes for disease outcomes has scarcely been studied in the general population. This information may be useful to identify personalized and targeted therapeutic strategies [13, 14].

Recently, an extensive overlap of asthma phenotypes was described [15]. However, only type 2-high, atopic, and eosinophilic asthma were examined. The extent of overlap with other phenotypes commonly reported in the literature, among adults with asthma from the general population remains unknown. Asthma phenotypes are frequently reported in the literature according to the high levels of systemic and local type 2-markers (B-Eos high and FeNO-high, respectively) [1,2,3,4, 16,17,18]. However, other distinct subgroups of asthma phenotypes are increasingly being reported due to its characteristics of steroid therapy resistance and lack of inflammatory markers: e.g. subjects with asthma without evidence of type 2 inflammation (Th2-low phenotype); obese asthmatic subjects (obesity-related asthma phenotype); and patients with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome [19,20,21,22].Therefore, we hypothesized that if, in general population, occurs a high proportion of overlap of commonly reported asthma phenotypes, there may be a need for improving the definition of asthma phenotypes. Additionally, asthma subjects with multiple phenotypes may have poorer asthma-related outcomes.

The aims of this study were to describe the proportion of overlap of five commonly reported asthma phenotypes: asthma with obesity (AwObesity), asthma with concurrent COPD (AwCOPD), B-Eos-high, FeNO-high and B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma, and to examine the association of their overlap with asthma-related outcomes, using population-based data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), 2007–2012.

Methods

Study design

The NHANES is a nationally representative survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population that uses a complex stratified, multistage probability sampling. Further details on NHANES survey design databases can be found in Additional file 1: Supplementary methods. The National Center for Health Statistics, Ethics Review Board approved NHANES protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Subjects selection

Six survey years (NHANES 2007–2012) were analyzed, resulting in 30,442 individuals of all ages (Fig. 1). We included adults (≥ 18 years-old) with current asthma (n = 1059), defined by a positive answer to the questions: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have asthma?” together with “Do you still have asthma?”, and either “wheezing/whistling in the chest in the past 12 months” or “asthma attack in the past 12 months.”

Variables

Demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), race/ethnicity, and educational status were analyzed. B-Eos count, FeNO and spirometric measurements, collected at the NHANES Mobile Examination Center were also examined. A detailed description of the procedures can be found elsewhere [23,24,25]. FeNO and spirometric measurements not fulfilling ATS/ERS recommendations [26, 27] were excluded (n = 653). After predicted values of basal FEV1 and FEV1/FVC were calculated [28], with a correction factor for ethnicity [29], abnormal lung function was defined if either one of them were less than the lower limit of normal (LLN), defined as lower fifth percentile of the reference population [30].

Prescription medications used last month were also analyzed [31]. More details regarding the inclusion of reliever and controller medications for asthma and the definitions of each asthma-related variable included in the analysis (asthma attack, asthma-related emergency department (ED) visit, work/school absenteeism, asthma symptoms, smoking status and rhinitis) are provided in the supplementary material (see Additional file 1: Supplementary methods).

Asthma phenotypes definition

A B-Eos count ≥ 300/mm3 was used to define an B-Eos-high asthma phenotype [32, 33], while FeNO-high was defined as FeNO ≥ 35 ppb [34]. Asthma patients with both B-Eos < 150/mm3 and FeNO < 20 ppb were categorized as B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma [35]. Additionally, we considered subjects with either B-Eos-high or FeNO-high as having “Type 2-high” asthma.

The AwObesity phenotype was defined by a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 in individuals with current asthma [36]. Finally, the AwCOPD phenotype was considered if participants ≥ 40 years-old had concurrent asthma and COPD, defined by a positive answer to “Has a doctor ever told you that you have chronic bronchitis/emphysema”, with age of diagnosis ≥ 40 years and having self-reported smoking history (being either a current or ex-smoker) [37, 38].

Statistical analysis

In accordance with the NHANES sampling design, the weights for each full sample 2-year mobile examination center were used to obtain weighted percentages adjusted to the US adult population.

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and weighted proportions, and continuous variables were described as median and first and third quartiles (Q1–Q3). Chi square test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare groups. To explore the association of concomitant (having at least 2 concurrent) phenotypes with each asthma-related outcome we performed multivariate logistic regression modelling. Separate models were run using each asthma-related outcome and abnormal lung function as dependent variable and having multiple phenotypes as independent variables. Adjustments were also made for potential confounders: sex, age, race, current smoking and rhinitis. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were presented, and model fit was assessed using the svylogitgof function [39].

According to age (< 40 or ≥ 40 years-old), a four- or five-set Venn-Euler diagram was used to quantify the proportion of individuals with different asthma phenotypes and to illustrate the overlap.

The diagrams were created using R software version 3.2.0 (“VennDiagram”, “venneuler” and “reshape2” packages) and all statistical analyses were performed in Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA), using the survey command to account for the complex sampling design and weights in the NHANES. The MI command was used to perform sensitivity analysis by multiple-imputation of missing values; however, to create the Venn-Euler diagrams, a listwise deletion for missing data was applied. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 18,619 adults included in NHANES 2007–2012 datasets, 1059 (5.6% [95% CI 5.1–5.9]) had current asthma (Fig. 1). Of these, 63% were female, and the median (Q1–Q3) age was 48.0 (32.0–62.0) years. After excluding subjects with missing data on the main variables, 634 individuals were included for phenotype classification (Fig. 1). Despite having all information available, 77 patients did not meet the criteria for any of the defined asthma phenotypes and were considered “non-classified”. These were non-obese subjects with asthma who did not meet the criteria for COPD, had B-Eos values ranging between 150 and 300/mm3, and FeNO ranging 20–34 ppb.

Demographic characteristics of adults with current asthma included and excluded from the analysis and patients with single (n = 271) and multiple phenotypes (n = 286) are described in Table 1.

There is a female predominance in both groups (64 and 66%, respectively). Subjects with multiple phenotypes were older (p = 0.003), had higher BMI (p < 0.001), were more often obese (p < 0.001) and ex-smokers (p = 0.003), and a higher proportion of patients were treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (p = 0.01), than those with only one phenotype. Females were more obese, regardless the number of concomitant asthma phenotypes (data not shown).

Phenotypes and overlap description

The weighted proportions of asthma phenotypes were (in descending order): 49% for AwObesity, 36% for B-Eos-high asthma, 26% for B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma, 18% for FeNO-high asthma, and 8% for AwCOPD (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics among all 5 asthma phenotypes and the “non-classified” group are described in Table 2.

There is a female predominance among all phenotypes, particularly in the B-Eos&FeNO-low (78%). Subjects with AwCOPD phenotype were the oldest group (median [Q1–Q3]: 61.0 [52.0–69.0] years-old), with the lowest proportion of individuals that had ≥ high school and lowest FEV1/FVC (0.63 [0.50–0.75]), comparing to the other phenotypes.

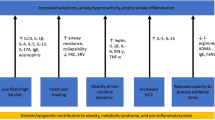

When categorized by age, < 40 (n = 227) and ≥ 40 years-old (n = 330), the most prevalent phenotypes were AwObesity (42 and 53%, respectively) and B-Eos-high asthma (34 and 37%). The less ones were FeNO-high asthma (18 and 19%) and AwCOPD (19% in the older group) (Fig. 2).

Venn-Euler diagrams quantifying the overlap among the asthma phenotypes, stratified by age. Data presented in weighted percentages to the US population. The overlap between AwCOPD with FeNO-high asthma (0.1%) and the overlap between AwCOPD, FeNO-high, AwObesity and B-Eos-high (0.5%) phenotypes are not shown

The areas of intersection in the four- and five-set Venn-Euler diagrams revealed 5 and 12 overlapping categories, and proportions of 17 and 12% of non-classified asthma subjects, respectively.

In both diagrams, a substantial total overlap was observed: 44% in subjects < 40 years-old and 54% in subjects ≥ 40 years-old. About 40% of the individuals in both age groups had two concomitant asthma phenotypes, 4% of the younger group had 3 concomitant phenotypes and 13% of the older group had ≥ 3 (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Furthermore, 1% of the older subjects had four concomitant asthma phenotypes: AwObesity, AwCOPD, FeNO-high, and B-Eos-high asthma.

The most prevalent overlaps in both groups (< 40 and ≥ 40 years-old) were AwObesity together with either B-Eos-high (15 and 12%, respectively) or B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma (13 and 11%) (Fig. 2).

Moreover, the proportions of subjects having AwObesity together with other phenotypes were high: 53% for the B-Eos-high phenotype, 48% for AwCOPD, 45% for the B-Eos&FeNO-low, and 44% for the FeNO-high phenotype. Also, the proportion of individuals having AwCOPD together with the B-Eos-high phenotype was high (36%), whereas the proportions were lower for the B-Eos&FeNO-low and the FeNO-high asthma phenotypes (15 and 10%, respectively) (data not shown).

In this population, only 12 and 15% of asthma subjects (< 40 and ≥ 40 years-old, respectively) with high B-Eos count had a concomitant high FeNO values (Fig. 2). Moreover, the two biomarkers were non-congruent across cut-offs. For example, when comparing groups with B-Eos count < 150/mm3 and 150–300/mm3, the proportion of asthma subjects having low FeNO (< 20 ppb), was not significantly different (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Associations between asthma-related outcomes and phenotype overlap

A comparison of the clinical characteristics of participants with one, two or three or more asthma phenotypes, stratified by age, is presented in Table 3 and no significant differences were observed in any age groups with regard to asthma attacks, asthma-related ED, ≥ 2 asthma symptoms, and use of ≥ 1 reliever. In the older group, the proportion of individuals with work/school absenteeism, ≥ 2 controller medications and with FEV1/FVC < LLN was significantly higher in participants with concomitant phenotypes than in those with a single phenotype (Table 3). In both age groups, the proportion of patients with FEV1 < LLN was significantly higher when participants presented multiple phenotypes, as well as they presented lower median FEV1% predicted values.

When analyzing the asthma-related outcomes in subjects with a single phenotype with those having specific combination of asthma phenotypes, the overall findings were that subjects having multiple phenotypes had significantly higher proportion of using ≥ 1 reliever and ≥ 2 controller medications and had decreased lung function, with the exception of those with the B-Eos&FeNO-low phenotype combined with any of the other phenotypes (Additional file 3: Table S2, and Additional file 4: Table S3).

Moreover, a lower proportion of subjects reporting asthma attacks was observed in subjects with AwObesity and either FeNO-high (26%) or AwCOPD (20%), compared to those with a single phenotype (67%) (Additional file 3: Table S2). Subjects with concomitant AwCOPD and B-Eos&FeNO-low phenotypes had the lowest proportion of ≥ 2 asthma symptoms (20%), but had the highest proportion of using ≥ 1 reliever medication (84%) as well as having FEV1 < LLN (71%).

In multivariate regression analysis, adjusting for co-variables, having multiple phenotypes was significantly associated with using ≥ 2 controller medications (aOR, 95% CI 2.03, 1.16–3.57), and having reduced FEV1 (3.21, 1.73–5.94) (Table 4). However, no associations were seen with asthma attacks, asthma-related ED, ≥ 2 asthma symptoms, work/school absenteeism, use of reliever medication or FEV1/FVC < LLN (Additional file 5: Table S4).

Furthermore, subjects aged ≥ 40 years-old, had significantly higher odds of using ≥ 2 controller medications and having FEV1 < LLN predicted, compared to those < 40 years-old, adjusted for covariates (Table 4). Being a current smoker was significantly associated with using ≥ 1 reliever medication (1.95, 1.35–2.83) and with reduced lung function: FEV1 < LLN predicted (2.01, 1.21–3.33) and FEV1/FVC < LLN (2.02, 1.16–3.51) and not associated with any other asthma-related outcomes (Table 4 and Additional file 5: Table S4).

The association between having concomitant phenotypes and using multiple controller medications was consistent when considering oral corticosteroids (OCS) separated from other controller medications (1.87, 1.09–3.21) (data not shown).

We also analyzed the potential bias of controller medications in the phenotype classification, particularly in the B-Eos-high and FeNO-high phenotypes (Additional file 6: Fig. S1). No significant differences in asthma-related treatment were found between the phenotypes, with exception for a higher proportion of patients treated with ICS within the FeNO-high and B-Eos-high phenotypes compared to those with B-Eos&FeNO-low phenotype (p = 0.03). When restricting to subjects with a single asthma phenotype no significant differences were found.

Moreover, sensitivity analyses showed that the proportion of total overlap (weighted 53%), and the associations between having multiple phenotypes and asthma outcomes were similar when imputing all missing values (data not shown). The goodness-of-fit test revealed adequate fitting for all regression models, except when using FEV1/FVC < LLN as dependent variable (Additional file 5: Table S4) and no statistically significant interactions between co-variables were observed.

Discussion

We report a substantial overlap of commonly reported asthma phenotypes among adults with current asthma in a large population sample, with almost half of them having two or more concomitant phenotypes. Furthermore, having multiple asthma phenotypes, regardless of their classification, was associated with poorer asthma outcomes, particularly the use of more controller medication and reduced lung function.

These findings illustrate the complexity and unique features of the concomitant asthma phenotypes when categorizing asthma in adults, using only the “classical” (hypothesis-driven) approach, based on measures readily available in the clinic (such as non-invasive biomarkers and medical records).

Hypothesis-driven asthma phenotypes are usually based on single dimensions of the disease, such as clinical symptoms, triggers, pathology or patterns of airway obstruction [16,17,18, 40,41,42]. However, evidence has shown that this approach is highly heterogenous, as it depends on the a priori assumptions and target population [43,44,45]. Also, it is of note that the 77 subjects with asthma that could not be classified as having any of the studied phenotypes, supports the fact that there is a considerable number of asthma patients whose clinical phenotype is not easily classified (e.g. asthmatics with irreversible airflow obstruction, patients with similar airways symptoms but with different pattern of airway inflammation), suggesting the presence of sub-phenotypes [1, 22, 44, 45].

In an attempt to explore the pathophysiology of specific asthma subgroups, and help stratify patients for targeted therapies, data-driven or unsupervised approaches (such as k-means, hierarchical clustering, partition-around-medoids methods or latent class analysis) are being applied in airways disease to identify “novel” accurate and distinct phenotypes, taking into account the heterogeneity and multidimensional characteristics of the disease [8, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Our study results seem to be in line with the view of those that argue for a combination of both hypothesis- and data-driven approaches as a way forward to progress our knowledge on asthma endotypes and clinical phenotypes in an iterative way [52,53,54]. The data-driven phenotypes studies obtained some of the phenotypes already defined by hypothesis-driven approaches (e.g. obese, non-eosinophilic asthmatics [8]; persistent airway inflammation [46]; low type-2 inflammation [49]; fixed obstructive, non-eosinophilic and neutrophilic [50]), but, importantly, they identified other phenotypes that differ by certain characteristics: clinical parameters [8, 47,48,49], clinical response to treatment [46, 52], and airway inflammation [49, 51]. Therefore, further studies are required to compare and validate the asthma phenotypes obtained using different unsupervised methods.

The high overlap of asthma phenotypes seen in this study was similar to the findings of Tran et al. [15], who used datasets from previous NHANES surveys to evaluate the overlap of asthma phenotypes. However, Tran et al. study focused on allergic asthma phenotypes, based on IgE levels, and was therefore limited to the 2005–2006 survey that lacks data on FeNO. We provided a broader analysis of phenotypes that included not only the eosinophil-based phenotype (associated more closely with IL-5-driven) and the one based on FeNO values (mostly dependent on IL-4/IL-13-driven) [12], but also other phenotypes not defined by biomarkers and in a much larger dataset.

In this study, we extended previous observations [7, 11] suggesting that FeNO and B-Eos count partially reflect different inflammatory pathways, representing a local and a systemic type 2-marker, respectively. We observed that only 12–15% of asthma subjects with high B-Eos count had concomitant high FeNO levels, in this population. Also, a similar proportion of subjects with multiple phenotypes was obtained when considering the “Type 2-high” phenotype, supporting the view that these two biomarkers are not interchangeable and that the use of both biomarkers in combination may allow for better targeted and personalized treatment for at least certain subsets of asthma patients [7, 10, 11].

The more prevalent combinations of phenotypes observed in this study were AwObesity together with either B-Eos-high or B-Eos&FeNO-low phenotypes. This supports the view that obesity-related asthma, despite often suggested to be a separate asthma phenotype associated with non-eosinophilic airway inflammation [9, 55, 56], may also be associated to eosinophilic inflammation.

Given the high prevalence in the US population, in this sample, obesity is likely to be a comorbidity, rather than the primary reason for asthma [57]; however, we defined the AwObesity phenotype as a separate group, since the interdependence on inflammatory markers to targeting different asthma therapies makes essential the accurate characterization of inflammation in obese asthmatic subjects [19, 58]. In addition, the relevance of defining the AwObesity phenotype is supported by the data as the weighted proportion of overlap is similar when excluding AwObesity or B-Eos-high phenotype from the analysis (data not shown). Moreover, the weighted proportion of subjects with “non-classified” asthma doubled when excluding the AwObesity phenotype (increasing to 32% in the < 40 years-old and 29% in ≥ 40 years old).

Having multiple asthma phenotypes was more common in older subjects and in non- and former- smokers; whether this is due to a general increase of comorbidities with age [58,59,60] and/or an interaction with environmental factors [61] cannot be specifically addressed by this study design. Nevertheless, when interpreting these results one should bear in mind that AwCOPD is associated to older age and prior/current smoking while FeNO increases with age and decreases with smoking [62, 63].

Interestingly, subjects with a higher number of concomitant asthma phenotypes presented reduced lung function and this association remained when controlling for potential confounders by multiple regression analysis. This shows that having multiple phenotypes is independently associated with reduced lung function, suggesting a cumulative effect of different disease processes.

Moreover, patients having several commonly reported asthma phenotypes had higher odds of using more controller medications, supporting the view that these patients are those with more complex disease and higher asthma morbidity [9, 15]. This also suggests that these asthma patients have an inadequate response to prescribed therapies, since lung function was reduced, and that they may represent a group of patients with the need for add-on treatment. However, the choice of specific treatments, such as biological therapies, will be more difficult considering the complexity introduced by having multiple phenotypes.

The lack of significant associations between multiple phenotypes and the other asthma-related outcomes may be difficult to understand. A possible explanation could be that the prescribed medication is effective against asthma symptoms and attacks but less effective against (subclinical) processes that cause long-term reduction in lung function. However, the results could also be related to data collection methods, as lung function measurement and the way medication use was ascertained, were less dependent on patient recall than the self-reported variables that were used for the outcomes with null results in the present study. Further studies should be done, adding the quantitative assessment of asthma attacks/asthma-related ED visits, and also including the age of asthma onset, that could have an influence on asthma-related outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, because of its cross-sectional design, it was not possible to evaluate interactions between phenotypes over time in patients with concomitant phenotypes, nor was it possible to determine which phenotype occurred first. Second, although there were differences between the included and excluded groups in the variables age, BMI, non-Hispanic white/black subjects, having finished high school and OCS use, the majority were not used for phenotypic classification and did not affect the outcomes, as shown in sensitivity analysis. Third, as our asthma and COPD definitions were based on self-reported diagnosis, rather than relying on lung function tests, the acquired information is subject to recall bias and misclassification. However, these definitions have been commonly used in NHANES reports [7, 11, 15] and have proven to be reasonably reliable [64, 65]. Moreover, we have used the most frequent combination of questions seen in epidemiological studies [65, 66], and we also included questions on recent wheeze and/or asthma attacks, which should reduce the risk of including individuals without true disease. Also, we stratified the analysis by age (at 40 years), as used in other COPD studies [37, 67], in order to improve the clinical value into the interpretation of phenotyping data, as the overlap among asthma phenotypes will be different among those less than age 40 and those older than 40 (with higher possibility of having COPD) [37]. Fourth, the lack of other biomarkers in the present NHANES years, prevented the analysis of other asthma phenotypes and the use of alternative definitions. However, we analyzed biomarkers of type 2-inflammation in both blood and exhaled air that previously have been shown to independently relate to asthma morbidity [7, 11]. Fifth, as there is no consensual definition of biomarker-defined asthma phenotypes, we based our definitions on cut-offs used in previous studies to discriminate patients in single asthma phenotypes [32,33,34,35], rather than on any reported specificity or sensitivity for predicting asthma morbidity or response to therapeutics [68, 69]. For high probability of eosinophilic inflammation, the cut-off value for FeNO has been suggested to be > 50 ppb for adults [70]. However, we chose a FeNO cut-off of 35 ppb, based on the mean baseline FeNO levels of patients included in randomized controlled trials of anti-IL-13 treatment [33, 69]. In spite of using this lower cut-off, 77 subjects with current asthma could not be classified as having any of the predefined phenotypes, indicating the need for better, and probably personalized, cut-offs for biomarkers in asthma.

Furthermore, we could not demonstrate a clear effect of ongoing controller medication in the phenotypic classification in our data. No significant associations were observed, probably at least partially explained with the exclusion of the participants with ICS/OCS use < 48 h prior to the exhaled NO measurements. Also, contrary to the expected, we observed a higher proportion of patients treated with ICS/OCS within both B-Eos-high and FeNO-high phenotypes than the B-Eos&FeNO-low phenotype. A plausible explanation is that subjects with ongoing inflammation have more clear asthma, with more symptoms, and, thus, a higher need of treatment. B-Eos&FeNO-low asthma is a heterogeneous group with less need of controller treatment, and because the treatment is ineffective, it may be that medication use and even prescription has been stopped.

Finally, even though we did not specifically analyze the overlap of asthma phenotypes in patients with severe asthma, the significant association between presenting more than one phenotype and being treated with multiple asthma controller medications suggests higher asthma severity in this subset [71]. Also, we did not consider individual environmental factors, such as air pollution and/or indoor allergens, that could influence asthma phenotypes. Further studies describing the overlap in patients with severe asthma and studies examining asthma patients exposed to different environmental factors, such as subjects who live in cities versus in rural areas are needed.

This study indicates that the overlap of commonly reported asthma phenotypes is observed also in non-selected asthma patients from the general population. Our findings highlight the importance of classifying asthma patients with regard to applicable phenotypes, rather than using a single asthma phenotype, to enable the development of adequate targeted strategies to avoid lung function impairment. However, further data is required, such as that from higher order analysis, using data-mining methods possibly combined with those that rely on predefined hypotheses. This synergy is expected to improve the knowledge on asthma phenotypes and, ultimately, to lead to more personalized treatment strategies [53, 54].

Conclusions

In conclusion, a prevalent overlap of commonly reported phenotypes was observed in asthma patients identified from the general population. Subjects classified as having multiple phenotypes used more controller medications and had reduced lung function. Thus, the complexity and unique features of concomitant asthma phenotypes may require a broader data analysis approach, based on a combination of clinical information and biomarkers resulting in better characterization of patients. This could lead to better asthma outcomes, particularly preserved lung function.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

adjusted odds ratios

- ATS/ERS:

-

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society

- AwCOPD:

-

asthma with concurrent COPD

- AwObesity:

-

asthma with obesity

- B-Eos:

-

blood eosinophils

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CI:

-

confidence intervals

- ED:

-

emergency department

- FeNO:

-

fraction of exhaled nitric oxide

- FEV1 :

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FEV1/FVC:

-

ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s to forced vital capacity

- ICS:

-

inhaled corticosteroids

- IgE:

-

immunoglobulin E

- IL:

-

interleukin

- LLN:

-

lower limit of normal

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (USA)

- OCS:

-

oral corticosteroids

- Q1:

-

first quartile

- Q3:

-

third quartile

- Th2:

-

T helper cell type 2

References

Froidure A, Mouthuy J, Durham SR, Chanez P, Sibille Y, Pilette C. Asthma phenotypes and IgE responses. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:304–19.

Corren J. Asthma phenotypes and endotypes: an evolving paradigm for classification. Discov Med. 2013;15(83):243–9.

Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–95.

Robinson D, Humbert M, Buhl R, Cruz AC, Inoue H, Korom S, Hanania NA, Nair P. Revisiting Type 2-high and Type 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(2):161–75.

Hastie AT, Moore WC, Li H, Rector BM, Ortega VE, Pascual RM, Peters SP, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Biomarker surrogates do not accurately predict sputum eosinophil and neutrophil percentages in asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(1):72.e12–80.e12.

Green RH, Brightling CE, Woltmann G, Parker D, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Analysis of induced sputum in adults with asthma: identification of subgroup with isolated sputum neutrophilia and poor response to inhaled corticosteroids. Thorax. 2002;57(10):875–9.

Malinovschi A, Fonseca JA, Jacinto T, Alving K, Janson C. Exhaled nitric oxide levels and blood eosinophil counts independently associate with wheeze and asthma events in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(4):821.e5–27.e5.

Jia G, Erickson RW, Choy DF, Mosesova S, Wu LC, Solberg OD, et al. Periostin is a systemic biomarker of eosinophilic airway inflammation in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):647.e10–54.e10.

Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):218–24.

Jia G, Erickson RW, Choy DF, Mosesova S, Wu LC, Solberg OD, Shikotra A, Carter R, Audusseau S, Hamid Q, et al. Identification of airway mucosal type 2 inflammation by using clinical biomarkers in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):710–9.

Malinovschi A, Janson C, Borres M, Alving K. Simultaneously increased fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels and blood eosinophil counts relate to increased asthma morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(5):1301.e2–308.e2.

Katial RK, Bensch GW, Busse WW, Chipps BE, Denson JL, Gerber AN, Jacobs JS, Kraft M, Martin RJ, Nair P, et al. Changing paradigms in the treatment of severe asthma: the role of biologic therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):S1–14.

Chung KF, Adcock IM. How variability in clinical phenotypes should guide research into disease mechanisms in asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(Suppl):S109–17.

Merritt F. Blood eosinophils: the Holy Grail for asthma phenotyping? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(2):90–1.

Tran TN, Zeiger RS, Peters SP, Colice G, Newbold P, Goldman M, Chipps BE. Overlap of atopic, eosinophilic, and TH2-high asthma phenotypes in a general population with current asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(1):37–42.

Borish L. The immunology of asthma: asthma phenotypes and their implications for personalized treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(2):108–14.

Hekking PPW, Bel EH. Developing and emerging clinical asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(6):671–80.

Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):716–25.

Gibeon D, Batuwita K, Osmond M, Heaney LG, Brightling CE, Niven R, et al. Obesity-associated severe asthma represents a distinct clinical phenotype: analysis of the British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Registry Patient cohort according to BMI. Chest. 2013;143(2):406–14.

Kobayashi S, Hanagama M, Yamanda S, Ishida M, Yanai M. Inflammatory biomarkers in asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;11:2117–23.

Carr TF, Zeki AA, Kraft M. Eosinophilic and noneosinophilic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):22–37.

Christenson SA, Steiling K, van den Berge M, Hijazi K, Hiemstra PS, Postma DS, Lenburg ME, Spira A, Woodruff PG, et al. Asthma-COPD overlap. Clinical relevance of genomic signatures of type 2 inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):758–66.

Complete Blood Count. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/cbc_g_met_he.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2017.

Respiratory Health ENO Procedures Manual. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/Respiratory_Health_ENO_Procedures_Manual.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2017.

Respiratory Health Spirometry Procedures Manual. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/spirometry_procedures_manual.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2017.

ATS/ERS. ATS/ERS Recommendations for Standardized Procedures for the Online and Offline Measurement of Exhaled Lower Respiratory Nitric Oxide and Nasal Nitric Oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):912–30.

Miller MR. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–38.

Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87.

Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, Smith LJ, Stukovsky KH, Barr RG. Performance of American Thoracic Society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults. Chest. 2010;137(1):138–45.

Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Hankinson J, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–68.

Prescription Medications - Drug Information. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/1999-2000/RXQ_DRUG.htm. Accessed 6 June 2017.

Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, Bateman ED, Brusselle GG, Bardin P, Murphy K, Maspero JF, O’Brien C, Korn S. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:355–66.

Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D, Spector S, Sher L, Skobieranda F, Wang L, Kirkesseli S, Rocklin R, Bock B, et al. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2455–66.

Dweik RA, Sorkness RL, Wenzel S, Hammel J, Curran-Everett D, Comhair SA, Bleecker E, Busse W, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, et al. Use of exhaled nitric oxide measurement to identify a reactive, at-risk phenotype among patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(10):1033–41.

McGrath KW, Icitovic N, Boushey HA, Lazarus SC, Sutherland ER, Chinchilli VM, Fahy JV, Asthma Clinical Research Network of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. A large subgroup of mild-to-moderate asthma is persistently noneosinophilic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(6):612–9.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(1):39–47.

Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespie S, Burney P, Mannino DM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–50.

Diagnosis of Diseases of Chronic Airflow Limitation: Asthma, COPD and Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS). http://goldcopd.org/asthma-copd-asthma-copd-overlap-syndrome/. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

Archer KJ, Lemeshow S. Goodness-of-fit test for a logistic regression model fitted using survey sample data. Stata J. 2006;6(1):97–105.

Hirano T, Matsunaga K. Late-onset asthma: current perspectives. J Asthma and Allergy. 2018;11:19–27.

Wenzel SE. Asthma: defining of the persistent adult phenotypes. Lancet. 2006;368:804–13.

Vonk JM, Jongepier H, Panhuysen CIM, Schouten JP, Bleecker ER, Postma DS. Risk factors associated with the presence of irreversible airflow limitation and reduced transfer coefficient in patients with asthma after 26 years of follow up. Thorax. 2003;58(4):322–7.

Bousquet J, Anto JM, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Chung KF, Roca J, et al. Systems medicine and integrated care to combat chronic noncommunicable diseases. Genome Med. 2011;3:43.

Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, Vogelmeier C, Brusselle G, Holgate S, Humbert M, Jones P, Gibson PG, Vestbo J, et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):410–9.

Zedan MM, Laimon WN, Osman AM, Zedan MM. Clinical asthma phenotyping: a trial for bridging gaps in asthma management. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4(2):13–8.

Wu W, Bleecker E, Moore W, Busse WW, Castro M, Chung KF, Calhoun WJ, Erzurum S, Gaston B, Israel E, et al. Unsupervised phenotyping of Severe Asthma Research Program participants using expanded lung data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1280–8.

Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(4):315–23.

Siroux V, Basagaña X, Boudier A, Pin I, Garcia-Aymerich J, Vesin A, Slama R, Jarvis D, Anto JM, Kauffmann F, Sunyer J. Identifying adult asthma phenotypes using a clustering approach. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(2):310–7.

Lefaudeux D, de Meulder B, Loza MJ, Peffer N, Rowe A, Baribaud F, Bansal AT, Lutter R, Sousa AR, Corfield J, et al. U-BIOPRED clinical adult asthma clusters linked to a subset of sputum omics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1797–807.

Loza MJ, Adcock I, Auffray C, Chung KF, Djukanovic R, Sterk PJ, Susulic VS, Barnathan ES, Baribaud F, Silkoff PE, et al. Longitudinally stable, clinically defined clusters of patients with asthma independently identified in the ADEPT and U-BIOPRED asthma studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(Suppl 1):S102–3.

Loza MJ, Djukanovic R, Chung KF, Horowitz D, Ma K, Branigan P, Barnathan ES, Susulic VS, Silkoff PE, Sterk PJ, et al. Validated and longitudinally stable asthma phenotypes based on cluster analysis of the ADEPT study. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):165.

Clemmer GL, Wu AC, Rosner B, McGeachie MJ, Litonjua AA, Tantisira KG, Weiss ST. Measuring the corticosteroid responsiveness endophenotype in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):274.e8–81.e8.

Belgrave D, Henderson J, Simpson A, Buchan I, Bishop C, Custovic A. Disaggregating asthma: big investigation vs. big data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;139(2):400–7.

Bousquet J, Anto JM, Akdis M, Auffray C, Keil T, Momas I, Postma DS, Valenta R, Wickman M, Cambon-Thomsen A, et al. Paving the way of systems biology and precision medicine in allergic diseases: the MeDALL success story. Allergy. 2016;71(11):1513–25.

Leiria LOS, Martins MA, Saad MJA. Obesity and asthma: beyond TH2 inflammation. Metabolism. 2015;64(2):172–81.

Bates JHT, Poynter ME, Frodella CM, Peters U, Dixon AE, Suratt BT. Pathophysiology to phenotype in the asthma of obesity. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(Supplement 5):S395–8.

Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Pertega S, Perez-Castro T, Sampedro M, Sanchez-Lastres J, San-Jose-Gonzalez MA, Bamonde L, Garnelo L, Valdés-Cuadrado L, Moure JD, et al. Obesity and asthma: an association modified by age. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41(3):176–80.

Amelink M, De Nijs SB, De Groot JC, Van Tilburg PMB, Van Spiegel PI, Krouwels FH, et al. Three phenotypes of adult-onset asthma. Allergy. 2013;68(5):674–80.

Ledford DK, Lockey RF. Asthma and comorbidities. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13(1):78–86.

Yanez A, Cho S-H, Soriano JB, Rosenwasser LJ, Rodrigo GJ, Rabe KF, Peters S, Niimi A, Ledford DK, Katial R, et al. Asthma in the elderly: what we know and what we have yet to know. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7(1):8.

Miller RL, Ho SM. Environmental epigenetics and asthma: current concepts and call for studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(6):567–73.

Jacinto T, Malinovschi A, Janson C, Fonseca J, Alving K. Evolution of exhaled nitric oxide levels throughout development and aging of healthy humans. J Breath Res. 2015;9(3):36005.

Jacinto T, Malinovschi A, Janson C, Fonseca J, Alving K. Differential effect of cigarette smoke exposure on exhaled nitric oxide and blood eosinophils in healthy and asthmatic individuals. J Breath Res. 2017;11(3):036006.

Halldin CN, Doney BC, Hnizdo E. Changes in prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in the US population and associated risk factors. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12(1):47–60.

Sá-Sousa A, Jacinto T, Azevedo LF, Morais-Almeida M, Robalo-Cordeiro C, Bugalho-Almeida A, Bousquet J, Fonseca JA. Operational definitions of asthma in recent epidemiological studies are inconsistent. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:24.

de Marco R, Cerveri I, Bugiani M, Ferrari M, Verlato G. An undetected burden of asthma in Italy: the relationship between clinical and epidemiological diagnosis of asthma. Eur Respir J. 1998;11(3):599–605.

Menezes AMB, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JRB, Muiño A, Lopez MV, Valdivia G, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet. 2005;366(9500):1875–81.

Hanania NA, Noonan M, Corren J, Korenblat P, Zheng Y, Fischer SK, Cheu M, Putnam WS, Murray E, Scheerens H, et al. Lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe asthma: pooled data from two randomised placebo-controlled studies. Thorax. 2015;70(8):748–56.

Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, Korenblat PE, Parsey MV, Arron JR, Harris JM, Scheerens H, Wu LC, Su Z, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1088–98.

Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, Olin AC, Plummer AL. Taylor DR; American Thoracic Society Committee on Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FENO) for Clinical Applications. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):602–15.

Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2016. http://ginasthma.org/2016-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 12 May 2017.

Authors’ contributions

RA, JAF, AM and KA contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing and revising the article. TJ, AMP and CJ contributed to data interpretation, writing and revising the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

RA is supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (PhD grant – Ref. PD/BD/113659/2015), Portugal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available in the NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Index.htm.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The NHANES survey operates under the approval of the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, Protocols #2005-06, and #2011-17 (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). All of the NHANES data meet the circumstances described in Policy #39, Research Using Publicly Available Datasets (Secondary Analysis) for use without application to Institutional Review Board. Moreover, all study participants provided written informed consent.

Funding

Project "NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000016" is financed by the North Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, and through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Methods.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Distribution and comparisons between the FeNO and B-Eos cut-offs used in this study, among individuals with current asthma.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Weighted percentages and comparisons of asthma-related outcomes among subjects with a single asthma phenotype versus: non-classified, and specific combinations of asthma phenotypes.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

Weighted percentages and comparisons of asthma-related outcomes among subjects with a single asthma phenotype versus: non-classified, and specific combinations of asthma phenotypes.

Additional file 5: Table S4.

Multivariable logistic regression models between each asthma-related outcome and having multiple asthma phenotypes, adjusted for co-variables.

Additional file 6: Fig. S1.

Proportions (weighted to the US population) of subjects taking asthma controller medications stratified into the different phenotypes, among all participants included for asthma phenotype classification (left) and only in those with a single phenotype (right). P-values <0.05 were indicated. NA: Non-applicable (not possible to determine because some participants had both B-Eos-high and FeNO-high asthma phenotypes).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Amaral, R., Fonseca, J.A., Jacinto, T. et al. Having concomitant asthma phenotypes is common and independently relates to poor lung function in NHANES 2007–2012. Clin Transl Allergy 8, 13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-018-0201-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-018-0201-3