Abstract

Biosynthesis of bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) nanorods was performed using dried fruit extracts of Hyphaene thebaica as a cost effective reducing and stabilizing agent. XRD, DRS, FTIR, zeta potential, Raman, HR-SEM, HR-TEM, EDS and SAED were used to study the main physical properties while the biological properties were established by performing diverse assays. The zeta potential is reported as − 5.21 mV. FTIR indicated Bi–O and V–O vibrations at 640 cm−1 and 700 cm−1/1120 cm−1. Characteristic Raman modes were observed at 166 cm−1, 325 cm−1 and 787 cm−1. High resolution scanning and transmission electron micrographs revealed a rod like morphology of the BiVO4. Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Fusarium solani indicated highest susceptibility to the different doses of BiVO4 nanorods. Significant protein kinase inhibition is reported for BiVO4 nanorods which suggests their potential anticancer properties. The nanorods revealed good DPPH free radical scavenging potential (48%) at 400 µg/mL while total antioxidant capacity of 59.8 µg AAE/mg was revealed at 400 µg/mL. No antiviral activity is reported on sabin like polio virus. Overall excellent biological properties are reported. We have shown that green synthesis can replace well established processes for synthesizing BiVO4 nanorods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Phytosynthesis of nanoscaled materials is an innovative approach often considered as a potential replacement for various chemical or physical methods. The inherent nature of the chemical process often led to produce toxic wastes while the physical means are often accompanied with elevated energy requirements (Ovais et al. 2018b; Khalil et al. 2019a, b; Shah et al. 2018; Hassan et al. 2018). Relative to the biologically synthesized nanoparticles, the chemically synthesize nanoparticles indicate low biocompatibility and possess latent biological risks. In order to keep the energy balance and mitigating environmental risks, plants are used as a versatile bio-reductant for the synthesis of various metal nanoparticles or their nanocomposites. Medicinal plants possess a diverse reservoir of phytochemicals which can reduce and stabilize the nanoparticles (Ovais et al. 2018c; Mohamed et al. 2019). Metal and metal based nanomaterials have diverse applications in different fields and therefore a number of scientists have adopted novel methods for synthesis and application (Manikandan et al. 2017; Thema et al. 2016; Devika et al. 2012; Mwakikunga et al. 2010; Khamlich et al. 2011).

Metal vanadate have been frequently looked for potential applications as implantable cardiac defibrillators, batteries, catalysis and photo catalysis (Sivakumar et al. 2015). However, bismuth vanadate has emerged as a promising candidate due to its unique physiochemical, optical and ferro-elastic properties (Sarkar and Chattopadhyay 2012). Various applications of BiVO4 has been well studied in water splitting, sensors, pollutant degradation etc. (Ma et al. 2019; Vo et al. 2019; Prado et al. 2019; Jaihindh et al. 2019; Hassan et al. 2019; Chomkitichai et al. 2019). Recently, there has been growing interest in biological applications of BiVO4. The AgI–BiVO4 composite material indicated excellent potential for inactivation of Escherichia coli in water disinfection (Guan et al. 2018). Similarly, the octahedral shaped BiVO4 synthesized via hydrothermal approach revealed inactivation of E. coli (80% to 100%) (Sharma et al. 2016). 100% inactivation of E. coli after 30 min of exposure to Ag loaded BiVO4 is also reported (Regmi et al. 2018). BiVO4 is among few materials that remain stable in mild pH neutral conditions (Lichterman et al. 2013).

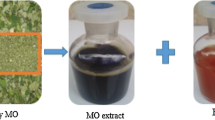

Due to the exciting properties and applications, there is considerable interest for the commercially scalable process for synthesizing BiVO4. Different methods like, ultrasonic-assisted, hydrothermal, pyrolysis, flame spray, chemical bath deposition, sonochemical, template-free solution and co-precipitation method have been explored to synthesize BiVO4 nanoparticles (Hu et al. 2018; Tao et al. 2019). Recently, plant extracts of Callistemon viminalis were used as a low cost reducing and stabilizing agents for biosynthesis of BiVO4 (Mohamed et al. 2018). Complementing to the limited literature on green avenues and biological properties of BiVO4, a green method was adopted by using dried fruit aqueous extracts of Hyphaene thebaica as green scaffolds for the synthesis of rod shaped BiVO4 which were subsequently studied for various biological properties. H. thebaica is a member of Arecaceae, locally referred as Doum (Arabic) and gingerbread tree (English). The medicinal applications of H. thebaica is well reported in the ethno-medicinal and folkloric scriptures (Khalil et al. 2019a, b). Various preparation of H. thebaica is reported for bleeding, haematuria, dyslipidemia, antihypertensive, diuretic diaphoretic, hypertension and lowering blood pressure etc. (Abdulazeez et al. 2019). In view of the medicinal applications and ethnopharmacological relevance, the fruit part of the H. thebaica was selected for biosynthesis.

Materials and methods

Processing of plants

The fruits of H. thebaica were obtained from (Aswan) Egypt, gently washed in running distill water for removing dust/impurities or any form of particulate matter, shade dried, powdered and used for extraction by heating 10 g of powdered fruit material to 400 mL of distil water at 100 °C/2 h on magnetic stirrer hotplate. Residual wastes were removed by filtering extracts for three times with Whattman filter paper and the remaining transparent extracts were used further.

Biosynthesis of BiVO4

Bismuth nitrate (2.448 g) was added to 50 mL aqueous extracts and heated at 100 °C/1 h for ensuring complete dissolution of precursor salt. In a separate flask, VOSO4 (1.126 g) was introduced to 50 mL extracts and heated at 100 °C/1 h. Change in color was observed. Both solutions were mixed to make a mix of bismuth and vanadium ions, proportionally mixed to form bismuth vanadate. The resultant precipitates were washed three times by centrifugation and dried at 100 °C. The dried precipitate was annealed at 500 °C for 2 h in a tube furnace which yielded yellow colored powder assumed as BiVO4. Annealing was performed to obtain a high degree crystallinity and purity.

Physical properties

Diverse techniques were applied to elucidate the main physical properties of green synthesized BiVO4. Powder X-ray diffraction was carried with diffractometer equipped with an irradiation line of 1.5406 A0 Cu Kα operating in Bragg–Brentano geometry. Debye Scherer formula was used to calculate the nano size while the data was compared with standard diffraction database. Vibrational characteristics were studied using Raman spectroscopy and FTIR. Diffuse reflectance spectra was recorded. Morphology was studied using HR-SEM and HR-TEM. Elemental composition was analyzed by Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy while Selected Area Electron Diffraction and zeta potential was also investigated. Once the physiochemical nature of the nanoparticles was established, they were then processed for analyzing their biomedical applications.

Antimicrobial properties

Simple well diffusion assay as described earlier (Khalil et al. 2014) was used at different concentration to investigate the antibacterial and antifungal potential of the BiVO4 nanorods in the concentration range of 4 mg/mL to 250 µg/mL. Test bacterial strains were Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 14490), Klebsiella pneumonia (ATCC 13883), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Escherichia coli (ATCC 15224) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9721), while test fungal strains were Aspergillus fumigates (FCBP 66), Aspergillus flavus (FCBP 0064), Aspergillus niger (FCBP 0918), Mucor sp. (FCBP 300) and Fusarium solani (FCBP 434). Briefly, the microbial cultures were standardized to an optical density of 0.5, corresponding to the MacFarland standards. 100 µL of inocula was dispensed on the Tryptic Soy Agar (bacterial media) and Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (fungal media) plates which was uniformly spread with sterile cotton swabs. Through sterile borer, 5 mm wells were made and 30 µL samples was introduced. Erythromycin and Amp B were used as positive control for bacteria and fungi respectively, while DMSO was added as a negative control. The bacterial cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h while the fungal plates were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. Zones of inhibition was measured and the MIC was considered as the least test concentration to cause microbial inhibition.

Protein kinase inhibition

Streptomyces 85 E cultured on ISP4 medium was used to assess the PK inhibition as described previously (Fatima et al. 2015), from 4 mg/mL to 250 µg/mL. The standardized culture (100 µL) was dispensed on the media plates and spread uniformly. 5 mm borer was used to make wells and the test samples were introduced followed by incubation for 72 h at 30 °C. Bald and clear zones were measured while DMSO and Streptomycin were used as negative and positive controls respectively.

Antioxidant assays

DPPH free radical scavenging and total antioxidant capacity were performed in the concentration range of 400–25 µg/mL, through a spectrophotometer based method as described previously (Hameed et al. 2019). The DPPH reagent solution was prepared by dissolving DPPH (9.6 mg) in methanol (100 mL). Test samples (20 µL) was added to DPPH reagent (180 µL), and the incubated for 20 min in dark. Results were recorded at 517 nm, and calculations were performed according to;

Total antioxidant capacity (Karunakaran et al. 2016) was investigated using phosphomolybdenum based method and the results were expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents per milligram.

Hemolysis

Hemolytic activity was performed as described previously (Malagoli 2007). Erythrocytes were isolated from freshly collected human blood in EDTA tubes, and their subsequent centrifugation at 14,000 RPM/5 min. 200 µL erythrocytes were added to 9.8 mL PBS for making erythrocytes suspension. The test nanoparticles in different concentrations were introduced in the Eppendorf tubes having an equal amount of the made erythrocytes suspension and incubated for 1 h at 35 °C. The reaction mix was then centrifuged at 10,000 RPM/10 min. Obtained supernatant was dispensed gently in 96 well plates and the hemoglobin release was monitored at 540 nm. Hemolysis was determined using the following formula;

Cell culture and antiviral experiments

Human Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells (RD), Human Laryngeal Carcinoma (HEp-2 cells) and L20B cells (mouse fibroblast cells) were enriched in Eagle’s Minimal Essential Medium (E’MEM) containing (10%) FBS. Propagation of Sabin like Poliovirus (Type 1) was done through HEp-2 cells supplemented with 2% FBS. Viral titers were determined using Karber formula after titration of the virus on RD cell (Thuy et al. 2013).

Assessment of cytotoxicity

MTT assay was used for cytotoxicity assessment with slight modifications (Lin et al. 2005). MTT assay is based on the mitochondrial dehydrogenase of viable cells, giving blue formazan product quantified spectrophotometrically. MTT assay was performed in 96-well plates, seeded with 100 µL RD cells, HEp-2 cells and L20B cells at a concentration of 3.5 × 105 cells/mL cultured in E’MEM (200 μL) containing FBS (10%) and incubated at 36 °C for 48 h in CO2 incubator to maintain a stable normal cell monolayers. Afterwards cells were treated with different doses of BiVO4 NPs (1000–15 μg/mL), and incubated for an additional 48 h at 36 °C. Cells were examined daily under inverted light microscope to determine the minimum concentration of BiVO4 NPs resulting in morphological changes in cells. 100 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was introduced to wells after removing the media and incubated (4 h/37 °C). MTT solution was then discarded and 50 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve insoluble formazan crystals and incubated (37 °C/30 min). Optical density (OD) was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer reader (victor × 3, Perkin Elmer). Data were obtained from triplicate wells. Cell viability was expressed with respect to the absorbance of the control wells (untreated cells), which were considered as 100% of absorbance. The percentage of cytotoxicity is calculated as

where A and B are the OD540 of untreated and of treated cells, respectively. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was defined as the compound’s concentration (μg/mL) required for the reduction of cell viability by 50%.

Assessment of antiviral activity

Confluent RD, Hep2C and L20B cell culture were treated with mixture of BiVO4 NPs and virus dilutions. Firstly, 100TCID50 poliovirus type 1 were diluted tenfold into two concentration of 10TCID50 and 1TCID50 in 2% E’MEM and introduce to non-cytotoxic concentrations of BiVO4 NPs (15 µg/mL) in ratio of 1:1 (v/v) and incubated for 1 h at 36 °C. After that, mixture of virus dilutions (100TCID, 10TCID50 and 1TCID50) was incubated with BiVO4 NPs (1 mg/mL to 15 µg/mL) in 96 well plate seeded with healthy monolayer of Hep2C cells (3.5 × 105 cells/mL) in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2. Cell growth 10% EMEM medium was decanted and replaced with 200 µL media respectively. Three controls were used including: (i) 50 μL of BiVO4 NPs at 15 µg/mL concentration (without poliovirus) were added to wells containing RD cells for BiVO4 NPs control (Magudieshwaran et al. 2019); 50 µL of poliovirus at concentration of 1TCID50, 10TCID50 and 100TCID50 was added to wells (iii) 200 μL of fresh maintenance medium was added for negative controls. The cultures were incubated at 36 °C post-infection, and cytopathic effect (CPE) was daily observed by inverted light microscopy. The cellular viability was determined through staining method using crystal violet. Optical density (OD) was measured at 490 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Results

Physical characterizations

Hyphaene thebaica dried fruit aqueous extracts were used as bio reductant for synthesis of novel BiVO4 nanorods. Different techniques were used to characterize the room temperature physiochemical properties of the nanorods. The overall process and study scheme has been summarized in Fig. 1. The extracts were treated separately with precursor salts of bismuth and vanadium giving light brown and blue color. Powdered X-ray diffraction was carried out to reveal the crystallographic properties and presence of BiVO4 nanorods. Figure 2a indicate the XRD spectra. Bragg peaks are observed at 18.6°, 28.9°, 30.5°, 34.4°, 35.2°, 39.5°, 42.4° 47.3°, 50.3°, 53.3°, 58.5° and 59.2° on 2 theta scale that corresponds to the crystallographic reflections of (110), (121), (040), (200), (002), (141), (051), (042), (202), (161), (321) and (123) respectively. These crystallographic peaks were in correspondence with the JCPDS pattern 00-014-0688 for Clinobisvanite phase monoclinic bismuth vanadium oxide (BiVO4). Sharpness of the peaks indicate a highly crystalline nature of the BiVO4. No other peaks were detected which suggested the single phase purity of the BiVO4 nanorods. The crystal structure belonged to space group I2/a with lattice parameters were deduced as 〈a〉 = 5.1 A°, 〈b〉 = 11.7 A°, and 〈c〉 = 5.09 A° correlating to the BiVO4 with yellow color. Scherer approximation revealed average size of ~ 7 nm as indicated in Table 1A.

After establishing single phase purity of BiVO4 nanorods, their elemental analysis were carried out using Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy as indicated in Fig. 2b. Spectral analysis confirmed the presence of “Bi”, “V” and “O”. The peak of “C” relates to the grid support. Some traces of “Cu” and “K” were also found that most probably emanates from the organic components of the fruit material.

Figure 2c indicate the FTIR spectra of the biosynthesized BiVO4 nanorods from 200 to 4000 cm−1. Main absorption peaks were observed centered at ~ 640 cm−1, ~ 700 cm−1, ~ 1120 cm−1, ~ 1625 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1. Peak centered at ~ 640 cm−1 can be ascribed to Bi–O (bending) while at ~ 700 cm−1 and ~ 1120 cm−1 to V–O symmetric and asymmetric vibrations (Khan et al. 2017). IR peaks centered at ~ 1625 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1 can be ascribed to the stretching vibrations of O–H group.

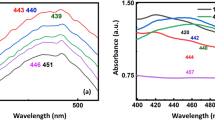

Raman spectroscopy is considered as a powerful technique to probe structure of metal oxides. Raman spectroscopy was carried out to further elaborate the vibrational properties of BiVO4 nanorods in the spectral range of 0 cm−1 to 1500 cm−1. Three noticeable raman peaks were observed centered at 166 cm−1, 325 cm−1 and 787 cm−1. The intense stretching mode of VO4 is observed at 787 cm−1. Raman peak centered at 325 cm−1 represents the asymmetric bending mode of VO4 tetrahedron (Brack et al. 2015). Peak centered at 166 cm−1, is attributed to the external mode vibration (Xu et al. 2018; Nikam and Joshi 2016). The raman spectra of BiVO4 nanorods is indicated in Fig. 2d. The UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectrum was recorded from 0 to 3000 nm. The BiVO4 nanorods revealed good visible light absorption with absorption edge at 487 nm. The steep shape is ascribed to the band gap transitions. The energy of the band gap is estimated to be ~ 2.54 eV. DRS spectra has been indicated in Fig. 3.

Inset Fig. 4A–F indicate the various high resolution microscopic images of the synthesized nanoparticles to establish their morphology. One can conclude the formation of well aligned rod shape of the BiVO4. The Selected Area Electron Diffraction pattern suggest crystalline nature of the nanorods as indicated in Fig. 4F. Zeta potential of the BiVO4 nanorods was recorded as − 5.21 mV. Results are indicated in Table 1B.

Antimicrobial properties

The antimicrobial properties of the BiVO4 nanorods have been explored against various bacterial and fungal strains. Results of the antibacterial and antifungal properties are indicated in Fig. 5a, b. Among the tested bacterial strains, B. subtilis revealed highest zone of inhibition (20 mm to 9.5 mm) in the concentration range of 4 mg/mL to 250 µg/mL. The least susceptible strain was found to be E. coli which revealed maximum zone of inhibition (11.5 mm) at 4 mg/mL. The order of the antibacterial activity of BiVO4 nanorods was found as B. subtilis > K. pneumoniae > S. epidermidis > P. aeruginosa > E. coli. Interestingly for P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis, the observed zone of inhibition was much larger than the positive control Erythromycin at the rate of 1 mg/mL. Similarly, against K. pneumoniae, the BiVO4 nanorods were found to be as effective as the positive control.

Among the five tested fungal strains, F. solani was observed as most susceptible fungal strain revealing zones ranging from 13 to 5.7 mm at the tested concentrations of BiVO4 nanorods. The order by which the antifungal potential observed was F. solani > A. niger > Mucor sp. > A. fumigatus > A. flavus. A. niger did not revealed any zones at 500 µg/mL or below, while A. fumigatus was found to be in effective at 250 µg/mL. Against F. solani and A. niger, the zones were revealed similar to the zones obtained from positive control (Amp B). Results of antifungal activity are summarized in Fig. 5b. Figure 6 indicate various selected images of the antibacterial and antifungal activities. Moreover, these activities revealed a dose dependent response.

Protein kinase inhibition

A simple assay based on the Streptomyces 85 E strain is used to screen PK inhibitors. Figure 7a, b indicate the protein kinase inhibition potential of the H. thebaica mediated BiVO4 nanorods. Excellent PK inhibition was revealed. The zones of inhibition at the tested concentration ranged from 13 to 8 mm. However, the zones of inhibition was much smaller then obtained for positive control.

Antioxidant assays

The antioxidant potential of the BiVO4 nanorods was determined using DPPH free radical scavenging and total antioxidant capacity. Moderate free radical scavenging potential is reported. At the highest tested concentration of 400 µg/mL, the percent scavenging was found to be 48%, which gradually declined as the concentration was lowered below 400 µg/mL. At the lowest tested concentration (25 µg/mL) of BiVO4 nanorods, 29% scavenging was observed. These results were complemented by the total antioxidant capacity which was determined as µg AAE/mg. Highest value (59.8 µg AAE/mg) of the ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE) was reported at 400 µg/mL while at lowest concentrations of 25 µg/mL, 26.9 µg AAE/mg was reported. Overall the antioxidant activity can be concluded as moderate and dose dependent. Results of antioxidant potential is indicated in Fig. 7c.

Hemolysis

Erythrocytes lysis assay was performed to evaluate the toxicity of BiVO4 on fresh isolated RBCs in test concentrations ranging from 600 to 12.5 µg/mL. The BiVO4 nanorods were observed to cause increased degree of hemolysis (75%) at higher concentrations 600 µg/mL, while percent hemolytic potential decreased with decrease in concentration. At lowest tested concentration (12.5 µg/mL), 14.8% hemolysis was observed. Overall, significant hemolytic nature of the BiVO4 nanorods is observed. Results are indicated in Fig. 7d.

Cytotoxicity of BiVO4 (RD cells, Hep2C and L20B)

Figure 8 indicate the experimental results revealed ~ 95% cell viability of RD cells (Human Rhabdomyosarcoma cells), Hep2C cells (Human Laryngeal Carcinoma) and L20B cells (Mouse Fibroblast cells) after incubation with both BiVO4 NPs (15 µg/mL). At higher concentration of BiVO4 NPs, the viability of cells started decreasing slightly compared to negative control. No cytopathic effects was indicated RD, Hep2C and L20 cells was revealed indicating compatibility of cell cultures with biological synthesized BiVO4 NPs after 2 h and 48 h incubation time. These obtained results suggest that both synthesized BiVO4 NPs are nontoxic to cells up to 48 h post-incubation at low concentration.

Antiviral activity of BiVO4

In order to investigate the antiviral activity of BiVO4, three concentrations (1TCID50, 10TCID50 and 100TCID50) of Sabin like poliovirus (Type 1) were incubated with BiVO4 NPs (15 µg/mL). Our results indicated that cells remained viable at 24 h post-infection. At 5th day of incubation, it was observed that most Hep2C cells were destroyed at viral concentration of 100TCID50, 10TCID50 and 1TCID50 across all the tested concentrations of BiVO4 NPs. It can be inferred that the BiVO4 nanorods were unable to inhibit the propagation of polio virus in the Hep2C cells. Complete destruction of the Hep2C cells was due to the intracellular propagation of the polio virus in Hep2C, cultured with 15 µg/mL of the BiVO4 nanorods.

Discussion

The interface of green nanotechnologies and medicinal plants have delivered excellent results over the previous decades. A number of biogenic metal based nanoparticles has revealed excellent results (Sathiyavimal et al. 2018). Green synthesized nanoparticles often exhibit multifunctional nature and therefore can be applied in diverse applications (Nasar et al. 2019; Venugopal et al. 2017). The interesting properties and potential applications of BiVO4 has fueled the growing research on their synthesis procedures which easy, scalable, green and cost effective. Different chemical and physical processes have been adopted for the synthesis of BiVO4, however, the potential of biological resources in their synthesis is largely untapped. Recently, we have established the successful synthesis of BiVO4 by using Callistemon viminalis floral extracts as bioreductant (Mohamed et al. 2018). Herein, a further detailed study was conducted on the physical as well as biological properties of BiVO4 nanorods, synthesized using the fruit extracts of H. thebaica. Plant extracts are reported to have a rich chemistry which has the tendency to catalyze redox reactions and subsequently stabilize the nanoparticles. The phytochemicals that usually take part in the reduction are mostly considered to be phenols, flavonoids, citric acid, membrane proteins, reductases, dehydrogenases etc. while the stabilizing moieties can be tannic acids, extracellular proteins, peptides, enzymes (Karatoprak et al. 2017; Akhtar et al. 2013; Elegbede et al. 2018). H. thebaica extracts are rich in the phenolic like cinnamic acid, sinapic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, Epicatechin, caffeic acid, coumarin and flavonoids like quercetin, hesperetin, naringin, glycosides, rutin (El-Beltagi et al. 2018) etc. which can serve as bioreductant and capping agents in biosynthesis of BiVO4 nanorods. This method is easily scalable, environmentally benign and easy to manage. Physical characterisation techniques established the unique structural and morphological nature of BiVO4. XRD data revealed Clinobisvanite phase of BiVO4 and the obtained peaks are consistent with previous results (Gawande and Thakare 2012; Sivakumar et al. 2015). In literature, three polymorphs of BiVO4 are reported which are Pucherite (orthorhombic), Dreyerite (tetragonal) and Clinobisvanite (monoclinic). Among these mineral forms, Clinobisvanite is most stable thermodynamically and possess significant photocatalytic potential (Zhao et al. 2011). Depending on the conditions, ferroelastic monoclonal-tetragonal-phase transitions are reported (Frost et al. 2006). The elemental analysis confirms the presence of “Bi”, “V” and “O” which establishes the synthesis of BiVO4. The infrared spectra of the synthesized nanorods affirms the potential role of phenolic components in plant extracts that have catalyzed the reduction and stabilization of BiVO4 nanorods. The role of phenolic compounds as reducing agents is well established (Ovais et al. 2018a; Soto et al. 2019). The role of Sulphur and Nitrogen rich protein compounds are also considered to play a significant role (Ballottin et al. 2016). The IR peaks obtained for Bi–O bending vibrations and V–O symmetric and asymmetric vibrations are consistent with previous studies (Khan et al. 2017). The Raman peaks were found to be in agreement with reported studies (Nikam and Joshi 2016; Xu et al. 2018). The shape and morphology of the BiVO4 was investigated as to be nanorods. The nanorods shaped morphology of the BiVO4 has been reported in the literature (Dubal et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Chen and Lin 2018). Zeta potential revealed a value of − 5.21 mV. The presence of negative charge suggest the presence of electrostatic repulsive forces which intends to repel the particles from one another, therefore, enhances stability by preventing aggregation. The surface charge on the nanoparticles and local environment plays an important role in determination of zeta potential (Chaudhuri and Malodia 2017).

To date, most of the studies revealing the antimicrobial potential of BiVO4 considered only the waste water disinfection. Recently, an innovative photocatalytic fabricated by Ni doping on BiVO4 revealed excellent degradation of ibuprofen (80%) within 90 min, while 92% reduction of E. coli after 5 h exposure to light was recorded. In addition, Ni-BiVO4 indicated excellent anti algal potential (Regmi et al. 2017). A novel BiVO4/InVO4 nanocomposite material revealed excellent sterilization potential against various bacterial strains i.e. E. coli (99.71%), S. aureus (99.55%), P. aeruginosa (99.54%) and A. carterae (96%) (Zhang et al. 2019). In a recent report, graphene based nanocomposite of BiVO4 (90 mg/L) was studied for antibacterial potential against B. subtilis and S. aureus using disc diffusion assay with, but no zone of inhibition was observed, suggesting a nontoxic nature of the BiVO4–GO nanocomposite (Zhao et al. 2019). Our work describe for the first time the antimicrobial potential of the phytosynthesized BiVO4. The physiochemical nature of the nanorods (surface coating, reducing-stabilizing agents, shape, size, surface morphology) plays important role in determining the antimicrobial activities (Zhang et al. 2016). The mechanism that drives the antimicrobial potential of the metal nanoparticles has mostly been attributed to the generation of reactive oxygen species. The present age of antibiotic resistance signifies the need to develop alternative antibiotics. The microorganisms tends to smartly evolve in order to develop resistance to the available treatments at a speedy rate. Furthermore, new antibiotics are not produced at the same pace at which microorganisms are getting resistant. Novel approaches like nanoantibiotics are considered vital to curb antibiotic resistance. BiVO4 nanorods have indicated excellent antimicrobial activities and therefore can be considered as a novel nanoantibiotics for future, before detailed evaluation of toxicity. The inhibition of protein kinase enzymes is considered a popular target for the anticancer therapies. Therefore, tremendous research has been devoted for identifying potent inhibitors of PK enzymes. Protein kinase are responsible for phosphorylating serine-threonine and tyrosine amino acids and play integral role in signaling differentiation and division of cells. The malfunctioned phosphorylation leads to the progression of cancer. By inhibiting the protein kinase that serve as a bridge for the signaling factors, cell division can be stopped ultimately hindering cancer progression. PK enzymes are vital for the growth of hyphae in Streptomyces 85 E strain and therefore, considered as a model organism. The cell culture experiments suggested the viability of the cells at low concentrations of the BiVO4 nanorods.

With the advances of the metal nanoparticles research medicinal plants have emerged as an exciting resource to be explored from green synthesis aspects. We have reported the biosynthesis of BiVO4 nanorods using H. thebaica fruit extracts as a low cost and green templating agents and studied them for possible biological applications. Excellent antibacterial and antifungal activities are reported. BiVO4 nanorods were most effective on Bacillus subtilis and Fusarium solani. Good protein kinase inhibition and antioxidant potential is revealed. The BiVO4 induced hemolysis at high concentrations. At low concentrations, the cell culture experiments revealed compatibility and non-toxicity. No potential antiviral activity was identified for BiVO4.

Green synthesis using medicinal plant extracts provides an excellent platform for assembling nanomaterials for different applications. The process is not only economical but converging evidence suggests enhanced compatibility of the biosynthesized nanoparticles making them ideal for nanomedicinal applications. Most of the work in this area has been dedicated to the silver and gold nanoparticles and their nanomedicinal applications which necessitates the need of extending this methodology to novel nanomaterials. BiVO4 has diverse applications in industries and further research is encouraged to use to different plant extracts to synthesize BiVO4 and explore their biomedical potential.

Availability of data and materials

All data material is available for use.

References

Abdulazeez M, Bashir A, Adoyi B, Mustapha A, Kurfi B, Usman A, Bala RK (2019) Antioxidant, hypolipidemic and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory effects of flavonoid-rich fraction of Hyphaene thebaica (Doum Palm) fruits on fat-fed obese wistar rats. Asian J Res Biochem. 1–11

Akhtar MS, Panwar J, Yun Y-S (2013) Biogenic synthesis of metallic nanoparticles by plant extracts. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 1(6):591–602

Ballottin D, Fulaz S, Souza ML, Corio P, Rodrigues AG, Souza AO, Gaspari PM, Gomes AF, Gozzo F, Tasic L (2016) Elucidating protein involvement in the stabilization of the biogenic silver nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett 11(1):313

Brack P, Sagu JS, Peiris TN, McInnes A, Senili M, Wijayantha KU, Marken F, Selli E (2015) Aerosol-assisted CVD of bismuth vanadate thin films and their photoelectrochemical properties. Chem Vapor Depos 21(1-2-3):41–45

Chaudhuri SK, Malodia L (2017) Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Calotropis gigantea: characterization and its evaluation on tree seedling growth in nursery stage. Appl Nanosci 7(8):501–512

Chen Y-S, Lin L-Y (2018) Synthesis of monoclinic BiVO4 nanorod array for photoelectrochemical water oxidation: seed layer effects on growth of BiVO4 nanorod array. Electrochim Acta 285:164–171

Chomkitichai W, Pama J, Jaiyen P, Pano S, Ketwaraporn J, Pookmanee P, Phanichphant S, Jansanthea P (2019) Dye mixtures degradation by multi-phase BiVO4 photocatalyst. In: Applied mechanics and materials, Vol 886, Trans Tech Publ, pp 138–145

Devika R, Elumalai S, Manikandan E, Eswaramoorthy D (2012) Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus and their antibacterial activity. Open Access Sci Rep 1:557

Dubal DP, Jayaramulu K, Zboril R, Fischer RA, Gomez-Romero P (2018) Unveiling BiVO 4 nanorods as a novel anode material for high performance lithium ion capacitors: beyond intercalation strategies. J Mater Chem A 6(14):6096–6106

El-Beltagi HS, Mohamed HI, Yousef HN, Fawzi EM (2018) Biological activities of the Doum Palm (Hyphaene thebaica L.) extract and its bioactive components. In: Antioxidants in foods and its applications. IntechOpen

Elegbede J, Lateef A, Azeez M, Asafa T, Yekeen T, Oladipo I, Aina DA, Beukes LS, Gueguim-Kana EB (2018) Biofabrication of gold nanoparticles using xylanases through valorization of corncob by Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma longibrachiatum: antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticoagulant and thrombolytic activities. Waste Biomass Valor. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0540-2

Fatima H, Khan K, Zia M, Ur-Rehman T, Mirza B, Haq I-U (2015) Extraction optimization of medicinally important metabolites from Datura innoxia Mill.: an in vitro biological and phytochemical investigation. BMC Complement Altern Med 15(1):376

Frost RL, Henry DA, Weier ML, Martens W (2006) Raman spectroscopy of three polymorphs of BiVO4: clinobisvanite, dreyerite and pucherite, with comparisons to (VO4)3-bearing minerals: namibite, pottsite and schumacherite. J Raman Spectrosc 37(7):722–732

Gawande SB, Thakare SR (2012) Graphene wrapped BiVO 4 photocatalyst and its enhanced performance under visible light irradiation. Int Nano Lett 2(1):11

Guan D-L, Niu C-G, Wen X-J, Guo H, Deng C-H, Zeng G-M (2018) Enhanced Escherichia coli inactivation and oxytetracycline hydrochloride degradation by a Z-scheme silver iodide decorated bismuth vanadate nanocomposite under visible light irradiation. J Colloid Interface Sci 512:272–281

Hameed S, Khalil AT, Ali M, Numan M, Khamlich S, Shinwari ZK, Maaza M (2019) Greener synthesis of ZnO and Ag–ZnO nanoparticles using Silybum marianum for diverse biomedical applications. Nanomedicine 14(6):655–673

Hassan D, Khalil AT, Saleem J, Diallo A, Khamlich S, Shinwari ZK, Maaza M (2018) Biosynthesis of pure hematite phase magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles using floral extracts of Callistemon viminalis (bottlebrush): their physical properties and novel biological applications. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2018.1434534

Hassan D, Khalil AT, Solangi AR, El-Mallul A, Shinwari ZK, Maaza M (2019) Physiochemical properties and novel biological applications of Callistemon viminalis-mediated α-Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Appl Organomet Chem 33:e5041

Hu Y, Chen W, Fu J, Ba M, Sun F, Zhang P, Zou J (2018) Hydrothermal synthesis of BiVO4/TiO2 composites and their application for degradation of gaseous benzene under visible light irradiation. Appl Surf Sci 436:319–326

Jaihindh DP, Thirumalraj B, Chen S-M, Balasubramanian P, Fu Y-P (2019) Facile synthesis of hierarchically nanostructured bismuth vanadate: an efficient photocatalyst for degradation and detection of hexavalent chromium. J Hazard Mater 367:647–657

Karatoprak GŞ, Aydin G, Altinsoy B, Altinkaynak C, Koşar M, Ocsoy I (2017) The Effect of Pelargonium endlicherianum Fenzl. root extracts on formation of nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activities. Enzyme Microb Technol 97:21–26

Karunakaran G, Suriyaprabha R, Rajendran V, Kannan N (2016) Influence of ZrO2, SiO2, Al2O3 and TiO2 nanoparticles on maize seed germination under different growth conditions. IET Nanobiotechnol 10(4):171–177

Khalil AT, Khan I, Ahmad K, Khan YA, Khan J, Shinwari ZK (2014) Antibacterial activity of honey in north-west Pakistan against select human pathogens. J Tradit Chin Med 34(1):86–89

Khalil AT, Ayaz M, Ovais M, Wadood A, Ali M, Shinwari ZK, Maaza M (2019a) In vitro cholinesterase enzymes inhibitory potential and in silico molecular docking studies of biogenic metal oxides nanoparticles. Inorg Nano-Metal Chem 48:441–448

Khalil O, Ibrahim R, Youssef M (2019b) A comparative assessment of phenotypic and molecular diversity in Doum (Hyphaene thebaica L.). Mol Biol Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-019-05130-w

Khamlich S, Manikandan E, Ngom B, Sithole J, Nemraoui O, Zorkani I, McCrindle R, Cingo N, Maaza M (2011) Synthesis, characterization, and growth mechanism of α-Cr2O3 monodispersed particles. J Phys Chem Solids 72(6):714–718

Khan I, Ali S, Mansha M, Qurashi A (2017) Sonochemical assisted hydrothermal synthesis of pseudo-flower shaped Bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) and their solar-driven water splitting application. Ultrason Sonochem 36:386–392

Lichterman MF, Shaner MR, Handler SG, Brunschwig BS, Gray HB, Lewis NS, Spurgeon JM (2013) Enhanced stability and activity for water oxidation in alkaline media with bismuth vanadate photoelectrodes modified with a cobalt oxide catalytic layer produced by atomic layer deposition. J Phys Chem Lett 4(23):4188–4191

Lin X, Huang Y, Fang M, Wang J, Zheng Z, Su W (2005) Cytotoxic and antimicrobial metabolites from marine lignicolous fungi, Diaporthe sp. FEMS Microbiol Lett 251(1):53–58

Liu C, Zhou J, Su J, Guo L (2019) Turning the unwanted surface bismuth enrichment to favourable BiVO4/BiOCl heterojunction for enhanced photoelectrochemical performance. Appl Catal B 241:506–513

Ma J-S, Lin L-Y, Chen Y-S (2019) Facile solid-state synthesis for producing molybdenum and tungsten co-doped monoclinic BiVO4 as the photocatalyst for photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Int J Hydrogen Energy 44:7905–7914

Magudieshwaran R, Ishii J, Raja KCN, Terashima C, Venkatachalam R, Fujishima A, Pitchaimuthu S (2019) Green and chemical synthesized CeO2 nanoparticles for photocatalytic indoor air pollutant degradation. Mater Lett 239:40–44

Malagoli D (2007) A full-length protocol to test hemolytic activity of palytoxin on human erythrocytes. Invertebr Surviv J 4(2):92–94

Manikandan A, Manikandan E, Meenatchi B, Vadivel S, Jaganathan S, Ladchumananandasivam R, Henini M, Maaza M, Aanand JS (2017) Rare earth element (REE) lanthanum doped zinc oxide (La:ZnO) nanomaterials: synthesis structural optical and antibacterial studies. J Alloy Compd 723:1155–1161

Mohamed H, Sone B, Dhlamini M, Maaza M (2018) Bio-synthesis of BiVO4 nanorods using extracts of Callistemon viminalis. MRS Adv 3(42–43):2479–2486

Mohamed HEA, Afridi S, Khalil AT, Zia D, Iqbal J, Ullah I, Shinwari ZK, Maaza M (2019) Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Hyphaene thebaica fruits and their in vitro pharmacognostic potential. Mater Res Express 6:1050c9

Mwakikunga B, Forbes A, Sideras-Haddad E, Scriba M, Manikandan E (2010) Self assembly and properties of C: WO 3 nano-platelets and C: VO2/V2O5 triangular capsules produced by laser solution photolysis. Nanoscale Res Lett 5(2):389

Nasar MQ, Khalil AT, Ali M, Shah M, Ayaz M, Shinwari ZK (2019) Phytochemical analysis, Ephedra Procera CA Mey. Mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles, their cytotoxic and antimicrobial potentials. Medicina 55(7):369

Nikam S, Joshi S (2016) Irreversible phase transition in BiVO4 nanostructures synthesized by a polyol method and enhancement in photo degradation of methylene blue. RSC Adv 6(109):107463–107474

Ovais M, Ahmad I, Khalil AT, Mukherjee S, Javed R, Ayaz M, Raza A, Shinwari ZK (2018a) Wound healing applications of biogenic colloidal silver and gold nanoparticles: recent trends and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:4305–4318

Ovais M, Khalil A, Ayaz M, Ahmad I, Nethi S, Mukherjee S (2018b) Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles via microbial enzymes: a mechanistic approach. Int J Mol Sci 19(12):4100

Ovais M, Khalil AT, Islam NU, Ahmad I, Ayaz M, Saravanan M, Shinwari ZK, Mukherjee S (2018c) Role of plant phytochemicals and microbial enzymes in biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(16):6799–6814

Prado TM, Carrico A, Cincotto FH, Fatibello-Filho O, Moraes FC (2019) Bismuth vanadate/graphene quantum dot: a new nanocomposite for photoelectrochemical determination of dopamine. Sens Actuators B Chem 285:248–253

Regmi C, Kshetri YK, Kim T-H, Pandey RP, Ray SK, Lee SW (2017) Fabrication of Ni-doped BiVO4 semiconductors with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performances for wastewater treatment. Appl Surf Sci 413:253–265

Regmi C, Dhakal D, Lee SW (2018) Visible-light-induced Ag/BiVO4 semiconductor with enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial performance. Nanotechnology 29(6):064001

Sarkar S, Chattopadhyay K (2012) Size-dependent optical and dielectric properties of BiVO4 nanocrystals. Physica E 44(7–8):1742–1746

Sathiyavimal S, Vasantharaj S, Bharathi D, Saravanan M, Manikandan E, Kumar SS, Pugazhendhi A (2018) Biogenesis of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs) using Sida acuta and their incorporation over cotton fabrics to prevent the pathogenicity of Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria. J Photochem Photobiol B 188:126–134

Shah A, Lutfullah G, Ahmad K, Khalil AT, Maaza M (2018) Daphne mucronata-mediated phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their novel biological applications, compatibility and toxicity studies. Green Chem Lett Rev 11(3):318–333

Sharma R, Singh S, Verma A, Khanuja M (2016) Visible light induced bactericidal and photocatalytic activity of hydrothermally synthesized BiVO4 nano-octahedrals. J Photochem Photobiol B 162:266–272

Sivakumar V, Suresh R, Giribabu K, Narayanan V (2015) BiVO4 nanoparticles: preparation, characterization and photocatalytic activity. Cogent Chem 1(1):1074647

Soto KM, Quezada-Cervantes CT, Hernández-Iturriaga M, Luna-Bárcenas G, Vazquez-Duhalt R, Mendoza S (2019) Fruit peels waste for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens. LWT 103:293–300

Tao X, Shao L, Wang R, Xiang H, Li B (2019) Synthesis of BiVO4 nanoflakes decorated with AuPd nanoparticles as selective oxidation photocatalysts. J Colloid Interface Sci 541:300–311

Thema F, Manikandan E, Gurib-Fakim A, Maaza M (2016) Single phase Bunsenite NiO nanoparticles green synthesis by Agathosma betulina natural extract. J Alloy Compd 657:655–661

Thuy NT, Huy TQ, Nga PT, Morita K, Dunia I, Benedetti L (2013) A new nidovirus (NamDinh virus NDiV): its ultrastructural characterization in the C6/36 mosquito cell line. Virology 444(1–2):337–342

Venugopal K, Rather H, Rajagopal K, Shanthi M, Sheriff K, Illiyas M, Rather RA, Manikandan E, Uvarajan S, Bhaskar M, Maaza M (2017) Synthesis of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) for anticancer activities (MCF 7 breast and A549 lung cell lines) of the crude extract of Syzygium aromaticum. J Photochem Photobiol B 167:282–289

Vo T-G, Tai Y, Chiang C-Y (2019) Multifunctional ternary hydrotalcite-like nanosheet arrays as an efficient co-catalyst for vastly improved water splitting performance on bismuth vanadate photoanode. J Catal 370:1–10

Xu X, Sun Y, Fan Z, Zhao D, Xiong S, Zhang B, Zhou S, Liu G (2018) Mechanisms for ·O2− and· OH production on flowerlike BiVO4 photocatalysis based on electron spin resonance. Front Chem 6:64

Zhang X-F, Liu Z-G, Shen W, Gurunathan S (2016) Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, applications, and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci 17(9):1534

Zhang X, Zhang J, Yu J, Zhang Y, Yu F, Jia L, Tan Y, Zhu Y, Hou B (2019) Enhancement in the photocatalytic antifouling efficiency over cherimoya-like InVO4/BiVO4 with a new vanadium source. J Colloid Interface Sci 533:358–368

Zhao Z, Li Z, Zou Z (2011) Structure and energetics of low-index stoichiometric monoclinic clinobisvanite BiVO4 surfaces. RSC Adv 1(5):874–883

Zhao J, Biswas MRUD, Oh W-C (2019) A novel BiVO4-GO-TiO2-PANI composite for upgraded photocatalytic performance under visible light and its non-toxicity. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:11888–11904

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the UNESCO-UNISA Africa Chair in Nanosciences and Nanotechnology, and the National Research Foundation of South Africa, Abdul Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) via the Nanosciences African Network to whom we are all grateful. Assistance in HR-SEM, HR-TEM, SAED etc. by the staff of Electron Microscopy Unit of the University of Western Cape is highly acknowledged. Support and assistance from the Molecular Systematics and Applied Ethnobotany Lab of the Department of Biotechnology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, is acknowledged.

Funding

UNESCO-UNISA Africa Chair in Nanosciences and Nanotechnology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HEAM, SK and TZ performed the experimental procedures. ATK, AA, ZKS and MM conceived and designed the work. MMA, ATK, HEAM, SK drafted the manuscript. MM, AA and ZKS reviewed and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

All authors agrees for publishing this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, H.E.A., Afridi, S., Khalil, A.T. et al. Phytosynthesis of BiVO4 nanorods using Hyphaene thebaica for diverse biomedical applications. AMB Expr 9, 200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0923-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0923-1