Abstract

Staphylococci and streptococci are common causes of intramammary infection in small ruminants, and reliable species identification is crucial for understanding epidemiology and impact on animal health and welfare. We applied MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP to 204 non-aureus staphylococci (NAS) and mammaliicocci (NASM) and to 57 streptococci isolated from the milk of sheep and goats with mastitis. The top identified NAS was Staphylococcus epidermidis (28.9%) followed by Staph. chromogenes (27.9%), haemolyticus (15.7%), caprae, and simulans (6.4% each), according to both methods (agreement rate, AR, 100%). By MALDI-TOF MS, 13.2% were Staph. microti (2.9%), xylosus (2.0%), equorum, petrasii and warneri (1.5% each), Staph. sciuri (now Mammaliicoccus sciuri, 1.0%), arlettae, capitis, cohnii, lentus (now M. lentus), pseudintermedius, succinus (0.5% each), and 3 isolates (1.5%) were not identified. PCR–RFLP showed 100% AR for Staph. equorum, warneri, arlettae, capitis, and pseudintermedius, 50% for Staph. xylosus, and 0% for the remaining NASM. The top identified streptococcus was Streptococcus uberis (89.5%), followed by Strep. dysgalactiae and parauberis (3.5% each) and by Strep. gallolyticus (1.8%) according to both methods (AR 100%). Only one isolate was identified as a different species by MALDI-TOF MS and PCR–RFLP. In conclusion, MALDI-TOF MS and PCR–RFLP showed a high level of agreement in the identification of the most prevalent NAS and streptococci causing small ruminant mastitis. Therefore, gap PCR–RFLP can represent a good identification alternative when MALDI-TOF MS is not available. Nevertheless, some issues remain for Staph. haemolyticus, minor NAS species including Staph. microti, and species of the novel genus Mammaliicoccus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mastitis is one of the most common and costly diseases affecting dairy sheep and goats. Therefore, monitoring and maintaining udder health is critical for small ruminant welfare and dairy production yield and quality [1, 2]. Infectious mastitis outbreaks can be caused by a wide variety of bacterial species, including the genera Staphylococcus (Staph.) and Streptococcus (Strep.) [2, 3]. Among Staphylococcus spp., non-aureus staphylococci (NAS) are the most prevalent and cause mainly subclinical intramammary infection (IMI) in both ewes and goats, leading to significant economic losses and reduced animal welfare [4, 5]. Recently, based on 16S rRNA sequences, five NAS species were reclassified and assigned to the novel genus Mammaliicoccus with Mammaliicoccus sciuri as the type species [6]. These species are collectively indicated by the acronym NASM. The large NASM bacterial group includes numerous species with different prevalence and epidemiology [2, 3, 7]. From studies on bovine subclinical mastitis, it is clear that some species are more associated with IMI, subclinical mastitis and somatic cell count (SCC) increase than others, which are instead more related to the farm environment or the mammary gland microbiota [6, 8,9,10]. Obtaining precise information on the species of NASM causing IMI and mastitis is therefore crucial for understanding the epidemiology and the respective roles in mammary gland health and disease in order to make more appropriate management decisions when these bacteria are isolated from the milk of small ruminants [7, 11].

In the microbiological laboratory, staphylococci and streptococci isolated from milk samples are mainly identified at the species level by means of biochemical tests or commercial biochemical galleries. However, these methods often fail in correctly identifying bacterial species of veterinary interest, also because they have been optimized for the strains associated with human infections [12,13,14,15]. In the last decade, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has emerged as a fast and accurate microbial identification approach [16] and is being successfully applied to bacteria isolated from bovine milk [17,18,19]. However, there are scarce reports of its performance in the identification of bacteria isolated from small ruminant milk, especially concerning staphylococci and sheep. Identification methods based on molecular rather than phenotypic characteristics can also provide a reliable alternative. Accordingly, the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sardegna (IZSSA) has developed, comparatively assessed, and implemented a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) method based on PCR amplification of the gap gene followed by AluI enzyme digestion for the identification of staphylococci and streptococci isolated from routine diagnosis [12, 13, 20].

In this study, we applied MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP for the species identification of staphylococci and streptococci isolated from the milk of sheep and goats with mastitis. Then, we compared their respective results to identify potential issues and solutions. Bacterial isolates were collected in Sardinia, the region with the largest small ruminant population in Italy.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

From January 2021 to May 2022, 204 NASM and 57 Streptococcus spp. were isolated from sheep and goat milk samples that routinely arrive at the IZSSA laboratories for identification of the IMI agent. Milk samples are accompanied by a form with a checkbox indicating the presence of clinical mastitis/visible milk alterations to be selected by the farm veterinarian. Only isolates derived from samples with these characteristics were included in the study. Milk samples were cultured following the standard procedures provided by the IZSSA. Briefly, 10 µL of milk were seeded in 5% sheep blood agar, incubated at 37 °C, and evaluated at 24 and 48 h. Upon growth of more than one morphologically different bacterial colony, identifications were not performed, and the sample was classified as “mixed bacterial flora”. Colonies were re-isolated in blood agar and examined with Gram stain, catalase, and coagulase tests to discriminate between staphylococci and streptococci. All isolates were stored at −20 °C in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, Beckton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) containing 20% glycerol, until further investigation. Only one NASM or streptococcus isolate was selected from each farm for identification by MALDI-TOF MS and PCR–RFLP, for a total of 261 non-duplicate isolates. A geographic map indicating the site of collection of each isolate in the different provinces of Sardinia was created with the software Microsoft Power BI using the farm code of each flock. The geo-referenced coordinates were extracted from the Banca Dati Nazionale (BDN) of the Italian Health Ministry. Additional file 1 illustrates the animal species originating the isolates and their geographical distribution.

MALDI-TOF MS for bacterial identification

At the IZSSA, all bacterial isolates were retrieved from the frozen archives, seeded in 5% sheep blood agar, and incubated at 37 °C. All isolates were passaged twice in the solid medium before identification at 24 h of growth. For MALDI-TOF MS analysis, the direct colony transfer protocol was applied. A small amount of an isolated colony was deposited in duplicate wells of disposable target plates using a toothpick, overlaid with 1 µL of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) solution in 50% acetonitrile, 47.5% water, 2.5% trifluoroacetic acid (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany), and left to dry. The target plates were prepared at the IZZSA in the afternoon, placed in an empty disposable target container once dry, and transported at room temperature to the animal infectious diseases laboratory at the University of Milan (MILab). In the morning of the following day, i.e. within 24 h as recommended by the MALDI Biotyper™ (MBT) Bruker user manual, the mass spectra were acquired with the MBT Microflex LT/SH MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH) in the positive mode. Each target plate included two spots of Bacterial Test Standard (Bruker Daltonik GmbH). The obtained spectra were interpreted against the MBT Compass® Library Revision H (2021), covering 3893 species/entries. The Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species included in this library revision are listed in Additional file 2. The two Mammaliicoccus species M. sciuri and M. lentus were still reported as Staph. sciuri and Staph. lentus in the library revision available at the time of this study. The following similarity log score thresholds were considered [16]: a log score ≥ 2.0 indicated a reliable species level identification, while a log score between 1.7 and 2.0 indicated a presumptive species level identification. Identifications with log scores below 1.7 were considered unreliable. All samples producing scores below 1.7 were processed again with the direct transfer, extended direct transfer, and protein extraction procedures. Specifically, for the extended direct transfer procedure, after depositing a small amount of the isolated colony in duplicate wells of the disposable target plate using a toothpick, the sample was overlaid with 1 µL of 70% formic acid and left to dry before adding the HCCA matrix solution. For the protein extraction procedure, bacteria from 4 isolated colonies were deposited into 300 µL of HPLC-grade water and vortexed. Then, 900 µL of ethanol absolute were added, the tube was vortexed again, and centrifuged for 2 min at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was removed carefully, and the pellet was left to dry for 10 min at room temperature. Once dried, the pellet was thoroughly resuspended in 25 µL of 70% formic acid, 25 µL of acetonitrile were added, and the suspension was mixed by pipetting. The sample was centrifuged again as above, and 1 µL of supernatant was deposited on the MALDI target and left to dry before overlaying with the HCCA matrix.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

At the IZSSA, genomic DNA was extracted from all 261 isolates and Type/Reference Strains (T/RS) as described previously [12]. Species identification was based on PCR amplification of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (gap) gene [20, 21]. The primers GF-1 (5’-ATGGTTTTGGTAGAATTGGTCGTTTA-3’) and GR-2 (5’-GACATTTCGTTATCATACCAAGCTG-3’) were used for staphylococci whereas the primers Strept-gap-F (5’-ACTCAAGTGTACGAACAAGT-3’) and Strept-gap-R (5’-GTCTTGCATTCCGTCGTAT-3’) for streptococci. PCR was performed in a reaction mixture containing 2.5 µL 10 × reaction buffer, 1.5 µL dNTPs 1.25 mM, 1 µL of each primer (25 pmol each), 1 µL DNA template, 0.5 µL Fast Taq (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and distilled water up to 25 µL. Reactions were carried out in an automated DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp 9700, Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Amplification conditions: initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 95 °C, 1 min at 50 °C (for staphylococci)/1 min at 54 °C (for streptococci), and 1 min at 72 °C with a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C. The 933-bp (staphylococci) and 945-bp (streptococci) amplicons were examined by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, stained with Sybr® Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and visualized under a UV transilluminator.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis

Fifteen microliters of both PCR amplifications were digested in a 30 µL volume containing 10 × FastDigest Green buffer, 0.25 µL of 20 mg/mL acetylated BSA, and 1 µL of FastDigest AluI enzyme (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min and directly loaded on the precast gels. Twenty microliters of digested gap amplifications were loaded in 12% Bis–Tris NuPAGE™ gels (Invitrogen) and then electrophoresed in a vertical gel apparatus. For staphylococci, the following 14 T/RS were used as reference strains for restriction pattern comparison: Staph. epidermidis ATCC 35983, Staph. xylosus ATCC 29971 T, Staph. saprophyticus ATCC 15305 T, Staph. capitis ATCC 27840 T, Staph. haemolyticus ATCC 29970 T, Staph. simulans ATCC 27848 T, Staph. warneri ATCC 27836 T, Staph. arlettae ATCC 43957 T, Staph. chromogenes ATCC 43764 T, Staph. equorum ATCC 43958 T, Staph. caprae ATCC 35538 T, Staph. sciuri ATCC 29062 T, Staph. hiycus ATCC 11249 T, and Staph. intermedius ATCC 29663 T. The gap PCR–RFLP patterns used for Staphylococcus species assignment are illustrated in Additional file 3. For streptococci, the following 7 T/RS were used as reference strains for restriction pattern comparison: Strep. uberis ATCC 700407, Strep. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae ATCC 43078 T, Strep. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis DSM 23147 T, Strep. agalactiae ATCC 13813 T, Strep. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus ATCC 49475, Strep. equi subsp. zooepidermicus NCTC 6180, and Strep. suis ATCC 43765. The gap PCR–RFLP patterns used for Streptococcus species assignment are illustrated in Additional file 4. All reference strain species identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS.

Amplicon sequencing

The gap gene amplicons of all isolates with PCR–RFLP profiles different from those of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus T/RS were sequenced at BMR Genomics with the Sanger sequencing option. The nucleotide sequences were compared to sequences in the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST).

Comparison of PCR–RFLP and MALDI-TOF MS results

All the data related to MALDI-TOF MS results, log scores, PCR–RFLP identification, gap gene sequencing results, and animal species, were plotted with Microsoft Excel for calculation of agreement ratio (AR), score distribution, and relative percentage values. Plots were generated with Microsoft Excel.

Results

Isolates and geographical distribution.

From January 2021 to May 2022, 204 NASM and 57 streptococci, for a total of 261 isolates, were obtained from sheep and goat milk samples sent to the IZSSA for microbiological analysis with a diagnosis of clinical mastitis/visible milk alterations by the farm veterinarian. Ovine isolates were 246, of which 191 NASM and 55 streptococci. Caprine isolates were 15, of which 13 NASM and 2 streptococci (Additional file 5).

MALDI-TOF MS of NASM isolates

All 204 isolates typed as NASM by culture and primary biochemical tests were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS identification by processing two spots per colony with the direct transfer procedure after 24 h of bacterial growth. This enabled the successful species identification of 201 isolates (98.5%), with log scores ≥ 2.00 in 165 (80.9%) and between 1.70–1.99 in 36 (17.6%). For the remaining 3 isolates (1.5%), log scores were < 1.70 with no identification possible even after a second round of identification with the direct transfer, extended direct transfer, and protein extraction procedures (Table 1).

The most frequently identified species were Staph. epidermidis (59, 28.9%), Staph. chromogenes (57, 27.9%), Staph. haemolyticus (32, 15.7%), Staph. caprae (13, 6.4%), and Staph. simulans (13, 6.4%), accounting for 85.3% of all NASM isolates. The remaining 13.2% was represented by Staph. microti (6, 2.9%), Staph. xylosus (4, 2.0%), Staph. equorum, petrasii, and warneri (3 each, 1.5%), Staph. sciuri (now M. sciuri) (2, 1.0%), and Staph. arlettae, capitis, cohnii, lentus (now M. lentus), pseudintermedius, and succinus (1 each, 0.5%).

MALDI-TOF MS of streptococcus isolates

MALDI-TOF MS identification of the 57 streptococcus isolates included in this study enabled the successful species identification of all isolates (100%) with log scores ≥ 2.00 in 53 (93.0%) and between 1.7–1.99 in 4 (7.0%). The most frequently identified species was Strep. uberis (51, 89.5%), followed by Strep. dysgalactiae and parauberis (2 each, 3.5%), and by Strep. gallolyticus and suis (1 each, 1.8%) (Table 1).

PCR–RFLP of NASM isolates

All 204 isolates typed as NASM by culture and primary biochemical tests were also subjected to species identification by gap PCR–RFLP. A total of 187 (91.7%) isolates showed restriction profiles identical to the reference strains, while 17 (8.3%) isolates showed a different PCR–RFLP pattern (Table 1). Upon gap gene sequencing (Additional file 6), 12 of them were identified as Staph. chromogenes (1), devriesei (1), epidermidis (1), haemolyticus (3) hyicus (1), jettensis (1), muscae (1), pseudintermedius (1), pseudoxylosus (1), and simulans (1), while 5 remaining isolates were classified as Staph. muscae (4) and Staph. devriesei (1) by matching with the isolate classified by gap gene sequencing (Table 2).

As a result, the top three identified species were Staph. epidermidis (61, 29.9%), Staph. chromogenes (58, 28.4%), and Staph. haemolyticus (37, 18.1%), followed by Staph. simulans (14, 6.9%) Staph. caprae (13, 6.4%), Staph. muscae (5, 2.5%), Staph. equorum and warneri (3, 1.5%), Staph. devriesei and xylosus (2 each, 1.0%), and Staph. arlettae, capitis, hyicus, jettensis, pseudintermedius, and pseudoxylosus (1 each, 0.5%).

PCR–RFLP of streptococcus isolates

Out of the 57 isolates typed as Streptococcus sp. by culture and primary biochemical tests, 53 (93.0%) showed gap PCR–RFLP profiles identical to the reference strains, while 4 (7.0%) did not. Upon gap gene sequencing (Additional file 7), these were identified as Strep. parauberis (2), Strep. uberis (1), and Strep. ruminantium (1) (Table 1 and Table 2). As a result, the top identified species was Strep. uberis (51, 89.5%), followed by Strep. dysgalactiae and parauberis (2 each, 3.5%), and by Strep. gallolyticus and ruminantium (1 each, 1.8%).

Comparison of gap PCR–RFLP and MALDI-TOF MS results

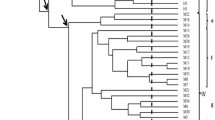

The species identification results obtained by MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP were in general agreement as detailed in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1.

For the 5 most frequently identified NAS (Staph. epidermidis, chromogenes, haemolyticus, caprae, and simulans) the agreement rate (AR) between MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP was 100%. Log scores were mostly ≥ 2.00, although for Staph. haemolyticus only 56.3% of the identifications had log scores ≥ 2.00. The AR between the two identification methods was 100% also for Staph. equorum, warneri, arlettae, capitis, and pseudintermedius. On the other hand, AR was 50% for Staph. xylosus and 0% for Staph. microti, Staph. petrasii, Staph sciuri (now M. sciuri), Staph. cohnii, Staph. lentus (now M. lentus), and Staph. succinus (Table 1).

The discordant species identifications between the two approaches are reported in Table 2. Of note was the case of 6 isolates identified as Staph. microti by MALDI-TOF MS and as Staph. muscae (5 isolates) and Staph. simulans (1 isolate) by gap sequencing. Among less frequently identified NASM species, only gap sequencing provided as identifications Staph. muscae, devriesei, hyicus, jettensis, and pseudoxylosus, while only MALDI-TOF MS provided Staph. microti, Staph. petrasii, Staph. sciuri (now M. sciuri), Staph. lentus (now M. lentus), and Staph. succinus.

For streptococci, the AR between MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP was 98.2% (56 of 57). The AR was 100% for the identification of Strep. uberis, with log scores ≥ 2.00 in 94.1% of cases. The AR was also 100% for Strep. dysgalactiae, parauberis, and gallolyticus. Only one species was identified as Strep suis by MALDI-TOF MS (log score 1.78) and as Strep. ruminantium by gap sequencing (Table 2).

Discussion

NAS and streptococci are the most prevalent etiological agents of small ruminant mastitis [2, 3]. However, NAS, mammaliicocci, and streptococci can also be found in milk as contaminants, as well as components of the mammary gland microbiota [6, 9, 10, 22]. Obtaining a reliable species identification is therefore essential for understanding their epidemiology and roles in mammary gland health and disease in order to make more meaningful management decisions [7, 8, 23].

In the last decade, MALDI-TOF MS has emerged as a dependable method for microbial identification and is being increasingly applied to bacteria and fungi isolated from bovine milk. When MALDI-TOF MS instrumentation is available in the laboratory, this approach is rapid, cost-effective, high-throughput, reliable, and does not require specific knowledge of mass spectrometry or molecular biology. An isolated colony is sufficient for identification and results are available within minutes. Thanks to the short analytical times, a high number of targets can be processed during the day, making it possible to identify thousands of microbial isolates. A further advantage of MALDI-TOF MS is the possibility of creating personalized spectrum libraries including isolates of specific interest, thereby improving bacterial identification reliability [24].

In the last decade, the IZSSA has developed and applied in its diagnostic routine a gap PCR–RFLP method enabling the identification of NAS and streptococci isolated from small ruminant milk [12, 13, 20]. This approach is reliable but moderately expensive in terms of materials and labor as it requires DNA extraction, PCR amplification, amplicon digestion, electrophoresis, and result interpretation by comparison with RFLP profiles from reference strains. The restricted number of reference strains is also a limitation, and it may eventually require gap gene amplicon sequencing for a tentative identification by homology. However, gap PCR–RFLP may represent a valuable alternative when MALDI-TOF instrumentation is not available. In fact, in spite of the low cost per test, the mass spectrometer acquisition costs are still too high for many veterinary diagnostic facilities, especially in low-resource contexts or in peripheral laboratories. As a further consideration, scarce data are available in the literature on the application of MALDI-TOF MS identification to the microorganisms isolated from small ruminant milk, especially concerning NAS and sheep.

In this work, we carried out the identification of NASM and streptococci isolated from the milk of small ruminants with mastitis by MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP integrated with amplicon sequencing. As a result, the species most frequently identified in our study were in line with those reported as causing small ruminant IMI worldwide [11, 25], that is Staph. epidermidis, chromogenes, haemolyticus, caprae and simulans for NAS, and Strep. uberis for streptococci. Notably, the two identification approaches showed a very high level of agreement, even for MALDI-TOF MS identifications with log scores ≥ 1.7. A cutoff log score ≥ 1.7 for species identification has been validated by various authors [19, 26, 27] as highly appropriate and accurate for bovine NAS. Han et al. [27] found that the ≥ 1.7 log score threshold enabled to reach a significantly higher level of NAS species identification without sacrificing specificity. Cameron et al. [28] also found that the reduction of the species level cutoff improved method performance from 64 to 92% when classifying bovine-associated NAS isolates. In the more recent study by Conesa et al. [19] the ≥ 1.7 score made it possible to successfully identify 36 more strains, as validated by the comparison with genotypic methods. Based on our results, a log score threshold of ≥ 1.7 could be considered reliable also for the most prevalent small ruminant NAS.

For Staph haemolyticus, however, the log scores were generally lower, as 43.7% of isolates had values < 2.0. Notably, 2 isolates were identified as Staph. haemolyticus by PCR–RFLP and as Staph. petrasii by MALDI-TOF MS with log scores > 2.0. Moreover, the gap gene of three isolates showed a very high sequence identity to Staph. haemolyticus but these were either identified as Staph. cohnii with a very low log score (1.7) or were not identified by MALDI-TOF MS. In our routine work, Staph. haemolyticus isolated from cow milk is also typically identified with lower scores among the most prevalent Staphylococcus spp. (M.F.A., personal communication). Staph. haemolyticus may be more problematic to identify because of a higher genomic variability and similarity of marker genes with other species. Wanecka et al. [14] found that 27 of 33 of their Staph. haemolyticus isolates had 99.5–100% similarity of the 16S rRNA gene with Staph. petrasii subsp. jettensis (now Staph. petrasii subsp. petrasii), Staph. hominis, Staph. epidermidis, or Staph. devriesei. Also recently, some Staph. haemolyticus have been reclassified as Staph. borealis [29]. Therefore, molecular techniques may have limitations including insufficient discriminatory power in the case of closely related species or the lack of quality of sequences deposited in the GenBank [30], as also observed in this work for gap gene sequencing. On the other hand, the absence of reference spectra for these highly similar minor species in the MALDI-TOF MS database might be the reason for their identification as Staph. haemolyticus with lower log scores.

All the 6 isolates identified as Staph. microti by MALDI-TOF MS could not be identified by gap PCR–RFLP. The gap gene sequence showed the highest identity with Staph. muscae (5 out of 6) and Staph. simulans (1 out of 6). Staph. microti has been described for the first time by Novàkovà et al. in 2010 [31] as an isolate from Microtus arvalis, the common vole, with Staph. muscae as the nearest relative. Its report as a staphylococcal species associated with mastitis in bovine and bubaline cows is increasing in association with the implementation of MALDI-TOF MS for NAS identification [18, 32, 33]. However, in consideration of the high similarity between these species, as well as with other closely related species not included in the Bruker spectrum library such as Staph. rostri, this will require further evaluation, possibly followed by spectrum library integration.

An isolate identified as Staph. petrasii by MALDI-TOF MS with log score ≥ 2.00 was identified as Staph. jettensis upon gap gene sequencing. The species description of Staph. petrasii has been emended, and Staph. jettensis should be reclassified as a novel subspecies within Staph. petrasii for which the name Staphylococcus petrasii subsp. jettensis subsp. nov [34]. As discussed above, the identification of this NAS as Staph. jettensis by gap gene sequencing may have resulted from matching with GenBank sequences that were not updated following taxonomic reclassification.

In 2020, five NAS species were proposed to be reassigned to the novel Mammaliicoccus genus, including Staph. sciuri and Staph. lentus, with M. sciuri as the type species [6]. The same authors proposed the reclassification of Staph. cohnii subsp. urealyticus as the novel species Staph. urealyticus. The Mammaliicoccus genus is not included in the current release of the Bruker library. Therefore, this should be considered when these species are identified by MALDI-TOF MS with the MBT System and the commercial spectrum library release available at the time of this study.

Concerning the two isolates identified as Staph. devriesei by gap gene sequencing and PCR–RFLP, one was not identified by MALDI-TOF MS, while the other was identified as Staph. xylosus with a score < 2.00. Moreover, one isolate identified as Staph. hyicus by gap gene sequencing was identified as Staph. sciuri by MALDI-TOF MS with score ≥ 2.00. Staph. devriesei falls in the Staph. haemolyticus group [11], and Staph. sciuri is also reported as belonging to a separate group than Staph. hyicus. Nevertheless, Staph. hyicus can be difficult to differentiate from Staph. agnetis [35] and the latter species was not present in the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum database.

An isolate was identified as Staph. xylosus by MALDI-TOF MS after a second round of identification with score 1.81. The same isolate was identified as Staph. pseudoxylosus by gap gene sequencing; however, this species was not included in the spectrum library. Analogously, no Strep. ruminantium spectra were present. However, for this latter species a presumptive identification as Strep. suis was provided, with score ≥ 1.7. Strep. ruminantium is indeed a new species of the suis group. Strep. suis includes 35 serotypes, of which 6 have been re-classified to other bacterial species [36]. Among them, Strep. suis serotype 33 has been recently classified as a new species, Streptococcus ruminantium [37], of which the reference strain was originally isolated from a lamb. As the two species are biochemically very similar, differentiation is difficult and a PCR specific for Strep. ruminantium has recently been described [38]. All other streptococci showed a very high agreement rate; therefore, both MALDI-TOF MS and PCR–RFLP enable to overcome the known difficulties in the identification of Gram-positive, catalase-negative cocci by biochemical reactions [39, 40] also with streptococci isolated from small ruminant milk.

As a further consideration, in this work we carried out microbial cultivation and target preparation at the IZSSA in Sassari, Sardinia, and MALDI-TOF MS identification at the University of Milan in Lodi, Lombardy, on the following day. According to the Bruker MBT User Manual, result reliability is maintained if spectra are generated within 24 h from target preparation. Therefore, this opens the possibility that these may be prepared in one laboratory and sent to a shared core facility for identification within the following day, provided that convenient logistic solutions are in place. This approach would enable to contain instrumental costs while centralizing the mass spectrometry instrumentation and the spectrum library, and it might also represent a reasonable alternative to the gap gene sequencing to integrate the PCR–RFLP identification approach. If planning such a setup, however, it would be advisable to thoroughly assess the impact of target transportation temperatures and conditions on reliability of the MALDI-TOF MS identification results.

In conclusion, our results concerning the species of NASM and streptococci associated with sheep and goat mastitis were in line with those reported as causing small ruminant IMI worldwide [11, 25]. For the most prevalent species, MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP provided comparable results. Therefore, gap PCR–RFLP can offer a reliable identification alternative when MALDI-TOF MS is not available, but restriction profiles differing from the validated reference isolates [12, 13, 20] may not be easily resolved by gap gene sequencing. Concerning MALDI-TOF MS, integrating the spectrum library with small ruminant strains of Staph. haemolyticus as well as of Staph. microti and their closely related species might further improve identification performances and it is advised.

References

Conington J, Cao G, Stott A, Bünger L (2008) Breeding for resistance to mastitis in United Kingdom sheep, a review and economic appraisal. Vet Rec 162:369–376. https://doi.org/10.1136/VR.162.12.369

Gelasakis AI, Mavrogianni VS, Petridis IG, Vasileiou NGC, Fthenakis GC (2015) Mastitis in sheep—the last 10 years and the future of research. Vet Microbiol 181:136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.07.009

Dore S, Liciardi M, Amatiste S, Brgagna S, Bolzoni G, Caligiuri V, Cerrone A, Farina G, Montagna CO, Saletti MA, Scatassa ML, Sotgiu G, Cannas EA (2016) Survey on small ruminant bacterial mastitis in Italy, 2013–2014. Small Rumin Res 141:91–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2016.07.010

Marogna G, Pilo C, Vidili A, Tola S, Schianchi G, Leori SG (2012) Comparison of clinical findings, microbiological results, and farming parameters in goat herds affected by recurrent infectious mastitis. Small Rumin Res 102:74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SMALLRUMRES.2011.08.013

Marogna G, Rolesu S, Lollai S, Tola S, Leori SG (2010) Clinical findings in sheep farms affected by recurrent bacterial mastitis. Small Rumin Res 88:119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2009.12.019

Madhaiyan M, Wirth JS, Saravanan VS (2020) Phylogenomic analyses of the Staphylococcaceae family suggest the reclassification of five species within the genus Staphylococcus as heterotypic synonyms, the promotion of five subspecies to novel species, the taxonomic reassignment of five Staphylococcus species to Mammaliicoccus gen. nov., and the formal assignment of Nosocomiicoccus to the family Staphylococcaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 70:5926–5936. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.004498

Bernier Gosselin V, Dufour S, Calcutt MJ, Adkins PRF, Middleton JR (2019) Staphylococcal intramammary infection dynamics and the relationship with milk quality parameters in dairy goats over the dry period. J Dairy Sci 102:4332–4340. https://doi.org/10.3168/JDS.2018-16030

De Buck J, Ha V, Naushad S, Nobrega DB, Luby C, Middleton JR, De Vliegher S, Barkema HW (2021) Non-aureus staphylococci and bovine udder health: current understanding and knowledge gaps. Front Vet Sci 8:360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.658031

Oikonomou G, Addis MF, Chassard C, Nader-Macias MEF, Grant I, Delbès C, Bogni CI, Le Loir Y, Even S (2020) Milk microbiota: what are we exactly talking about? Front Microbiol 11:60. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00060

Derakhshani H, Fehr KB, Sepehri S, Francoz D, De Buck J, Barkema HW, Plaizier JC, Khafipour E (2018) Invited review: microbiota of the bovine udder: contributing factors and potential implications for udder health and mastitis susceptibility. J Dairy Sci 101:10605–10625. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14860

Vasileiou NGC, Chatzopoulos DC, Sarrou S, Fragkou IA, Katsafadou AI, Mavrogianni VS, Petinaki E, Fthenakis GC (2019) Role of staphylococci in mastitis in sheep. J Dairy Res 86:254–266. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029919000591

Onni T, Sanna G, Cubeddu GP, Marogna G, Lollai S, Leori S, Tola S (2010) Identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from ovine milk samples by PCR-RFLP of 16S rRNA and gap genes. Vet Microbiol 144:347–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.01.016

Onni T, Vidili A, Bandino E, Marogna G, Schianchi S, Tola S (2012) Identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from caprine milk samples by PCR-RFLP of groEL gene. Small Rumin Res 104:185–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.10.004

Wanecka A, Król J, Twardoń J, Mrowiec J, Korzeniowska-Kowal A, Wzorek A (2019) Efficacy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as well as genotypic and phenotypic methods in identification of staphylococci other than Staphylococcus aureus isolated from intramammary infections in dairy cows in Poland. J Vet Diagn Invest 31:523–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638719845423

Vanderhaeghen W, Piepers S, Leroy F, Van Coillie E, Haesebrouck F, De Vliegher S (2015) Identification, typing, ecology and epidemiology of coagulase negative staphylococci associated with ruminants. Vet J 203:44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.11.001

Seng P, Rolain J-M, Fournier PE, La Scola B, Drancourt M, Raoult D (2010) MALDI-TOF-mass spectrometry applications in clinical microbiology. Future Microbiol 5:1733–1754. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.10.127

Nonnemann B, Lyhs U, Svennesen L, Kristensen KA, Klaas IC, Pedersen K (2019) Bovine mastitis bacteria resolved by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J Dairy Sci 102:2515–2524. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-15424

Hamel J, Zhang Y, Wente N, Krömker V (2020) Non-S aureus staphylococci (NAS) in milk samples: Infection or contamination? Vet Microbiol 242:108594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108594

Conesa A, Dieser S, Barberis C, Bonetto C, Lasagno M, Vay C, Odierno L, Porporatto C, Raspanti C (2020) Differentiation of non-aureus staphylococci species isolated from bovine mastitis by PCR-RFLP of groEL and gap genes in comparison to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Microb Pathog 149:104489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104489

Rosa NM, Agnoletti F, Lollai S, Tola S (2019) Comparison of PCR-RFLP, API® 20 Strep and MALDI-TOF MS for identification of Streptococcus spp. collected from sheep and goat milk samples. Small Rumin Res 180:35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2019.09.023

Yugueros J, Temprano A, Berzal B, Sánchez M, Hernanz C, Luengo JM, Naharro G (2000) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding gene as a useful taxonomic tool for Staphylococcus spp. J Clin Microbiol 38:4351–4355. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.38.12.4351-4355.2000

Addis MF, Tanca A, Uzzau S, Oikonomou G, Bicalho RC, Moroni P (2016) The bovine milk microbiota: insights and perspectives from -omics studies. Mol Biosyst 12:2359–2372. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6MB00217J

Gosselin VB, Lovstad J, Dufour S, Adkins PRF, Middleton JR (2018) Use of MALDI-TOF to characterize staphylococcal intramammary infections in dairy goats. J Dairy Sci 101:6262–6270. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14224

Kostrzewa M, Schubert S (2016) MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry in Microbiology. Caister Academic Press, UK

Vanderhaeghen W, Piepers S, Leroy F, Van Coillie E, Haesebrouck F, De Vliegher S (2014) Invited review: effect, persistence, and virulence of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species associated with ruminant udder health. J Dairy Sci 97:5275–5293. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-7775

Mahmmod YS, Nonnemann B, Svennesen L, Pedersen K, Klaas IK (2018) Typeability of MALDI-TOF assay for identification of non-aureus staphylococci associated with bovine intramammary infections and teat apex colonization. J Dairy Sci 101:9430–9438. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14579

Han HW, Chang HC, Hunag AH, Chang TC (2015) Optimization of the score cutoff value for routine identification of Staphylococcus species by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 83:349–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.08.003

Cameron M, Perry J, Middleton JR, Chaffer M, Lewis J, Keefe GP (2018) Short communication: evaluation of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and a custom reference spectra expanded database for the identification of bovine-associated coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Dairy Sci 101:590–595. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-13226

Pain M, Wolden R, Jaén-Luchoro D, Salvà-Serra F, Piñeiro Iglesias B, Karlsson R, Klingenberg C, Cavanagh JP (2020) Staphylococcus borealis sp. nov., isolated from human skin and blood. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 70:6067–6068. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.004499

Heikens E, Fleer A, Paauw A, Florijn A, Fluit AC (2005) Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic methods for species-level identification of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol 43:2286–2290. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.5.2286-2290.2005

Nováková D, Pantůček R, Hubálek Z, Falsen E, Busse HJ, Schumann P, Sedláček I (2010) Staphylococcus microti sp. nov., isolated from the common vole (Microtus arvalis). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:566–573. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.011429-0

Król J, Wanecka A, Twardoń J, Mrowiec J, Dropińska A, Bania J, Podkowik M, Korzeniowska-Kowal A, Paściak M (2016) Isolation of Staphylococcus microti from milk of dairy cows with mastitis. Vet Microbiol 182:163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.11.018

Addis MF, Maffioli EM, Penati M, Albertini M, Bronzo V, Piccinini R, Tangorra F, Tedeschi G, Cappelli G, Di Vuolo G, Vecchio D, De Carlo E, Ceciliani F (2022) Peptidomic changes in the milk of water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) with intramammary infection by non-aureus staphylococci. Sci Rep 12:8371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12297-z

De Bel A, Švec P, Petráš P, Sedláček I, Pantůček R, Echahidi F, Vandamme DP (2014) Reclassification of Staphylococcus jettensis De Bel, et al 2013 as Staphylococcus petrasii subsp. jettensis subsp. nov. and emended description of Staphylococcus petrasii Pantucek et al. 2013. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:4198–4201. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.064758-0

Adkins PRF, Middleton JR, Calcutt MJ, Stewart GC, Fox LK (2017) Species identification and strain typing of Staphylococcus agnetis and Staphylococcus hyicus isolates from bovine milk by use of a novel multiplex PCR assay and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol 55:1778–1788. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02239-16

Gottschalk M, Lacouture S, Fecteau G, Desrochers A, Boa A, Saab ME, Okura M (2020) Canada: Isolation of Streptococcus ruminantium (Streptococcus suis-like) from diseased ruminants in Canada. Can Vet J 61:473

Tohya M, Sekizaki T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T (2018) Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus ruminantium sp. nov. GUT-187T (=DSM 104980T =JCM 31869T), the type strain of S. ruminantium, and comparison with genome sequences of Streptococcus suis strains. Genome Biol Evol 10:1180–1184. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evy078

Okura M, Maruyama F, Ota A, Tanaka T, Matoba Y, Osawa A, Sadaat SM, Osaki M, Toyoda A, Ogura Y, Hayashi T, Takamatsu D (2019) Genotypic diversity of Streptococcus suis and the S suis-like bacterium Streptococcus ruminantium in ruminants. Vet Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-019-0708-1

Scillieri Smith JC, Moroni P, Santisteban CG, Rauch BJ, Ospina PS, Nydam VD (2020) Distribution of Lactococcus spp. in New York State dairy farms and the association of somatic cell count resolution and bacteriological cure in clinical mastitis samples. J Dairy Sci 103:1785–1794. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-16199

Fortin M, Messier S, Paré J, Higgins R (2003) Identification of catalase-negative, non-beta-hemolytic, gram-positive cocci isolated from milk samples. J Clin Microbiol 41:106–109

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Scrugli for the map of Sardinia including all isolates analyzed in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by funds from the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sardegna and from the University of Milan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NMR, MP, and SF-P performed the laboratory experiments. MFA and ST designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

13567_2022_1102_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Additional file 3: Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) pattern of PCR products of the gap gene obtained after digestion with Alu I and used for Staphylococcus species assignment.

13567_2022_1102_MOESM4_ESM.docx

Additional file 4: Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) pattern of PCR products of the gap gene obtained after digestion with Alu I and used for Streptococcus species assignment.

13567_2022_1102_MOESM5_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 5: Excel file detailing PCR–RFLP identification, gap gene sequencing information where obtained, MALDI-TOF MS identification, best log score, and animal species.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosa, N.M., Penati, M., Fusar-Poli, S. et al. Species identification by MALDI-TOF MS and gap PCR–RFLP of non-aureus Staphylococcus, Mammaliicoccus, and Streptococcus spp. associated with sheep and goat mastitis. Vet Res 53, 84 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01102-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-022-01102-4