Abstract

Background

Depressive disorders often remain undiagnosed or are treated inadequately. Online-based programs may reduce the present treatment gap for depressive disorders and reduce disease-related costs. This study aimed to examine the potential of the internet intervention “deprexis” to reduce the total costs of statutory health insurance. Changes in depression severity, health-related quality of life and impairment in functioning were also examined.

Method

A total of 3805 participants with, at minimum, mild depressive symptoms were randomized to either a 12-week online intervention (deprexis) or a control condition. The primary outcome measure was statutory health insurance costs, estimated using health insurers’ administrative data. Secondary outcomes were: depression severity, health-related quality of life, and impairment in functioning; assessed on patient’s self-report at baseline, post-treatment, and three-months’ and nine-months’ follow-up.

Results

In both groups, total costs of statutory health insurance decreased during the study period, but changes from baseline differed significantly. In the intervention group total costs decreased by 32% from 3139€ per year at baseline to 2119€ in the study year (vs. a mean reduction in total costs of 13% in the control group). In comparison to the control group, the intervention group also showed a significantly greater reduction in depression severity, and impairment in functioning and a significantly greater increase in health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

The study underlines the potential of innovative internet intervention programs in treating depressive disorders. The results suggest that the use of deprexis over a period of 12 weeks leads to a significant improvement in symptoms with a simultaneous reduction in the costs of statutory health insurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental illnesses are responsible for a considerable part of the burden of disease and health care expenditure in Germany and other countries. They account for about 13% of the direct medical costs in Germany (thereof 19% due to depression) and cause considerable indirect costs [1]. The most common form of depressive disorders is major depression. The lifetime prevalence of a major depression is estimated at 11.6% to 13.0% in German adults, with women having nearly twice as high a risk of disease compared to men [2,3,4,5,6]. Aggravatingly, depressive episodes often persist for longer periods of time and become chronic [7]. From a societal perspective, depressive disorders are associated with a substantial loss of resources. Compared to people without depression, patients with depressive disorders report twice as many days of incapacity for work [8]; employees had an average absence of 51.8 days due to depressive episodes in 2014 [9]. In addition to indirect costs due to disease related productivity losses, depressive disorders are associated with high health care costs. Thus, the estimated annual direct treatment costs for Germany range between €686 [10] and €€2073 [11] per patient within different studies. The differences in average patient costs can be traced back to various conceptual issues, different methodological costing procedures and large differences in sample sizes. A recent study by Wagner et al. reports annual depression-related costs of €797, which is far closer to the €686 reported by Friemel et al. than to the €2073 reported by Salize et al., which seem rather overestimated [12, 13]. The total direct costs of depression in Germany were estimated at 5,2 billion Euro for the whole population [6, 14].

Despite differentiated guidelines and a well-developed health care system, depressive episodes are rarely identified early and treated adequately. Only one-third of all clearly clinically relevant depressive disorders are detected [15]. This globally documented treatment gap in the management of mental illnesses [16] may be counteracted by internet-based self-help interventions. This form of intervention is particularly relevant as a treatment for mild to moderate depression [17, 18]. Advantages are low threshold, local and temporal independence, reductions in waiting time for face-to-face treatment, empowerment and anonymity [18, 19].

Different studies along randomized controlled trials and some meta-analyses have provided evidence for the clinical effectiveness of online-based therapy programs for the treatment of depression (especially in the treatment of mild to moderate depressive symptoms). A meta-analysis by Karyotaki et al. found that self-guided internet-based behavioral therapy was significantly more effective with respect to depressive symptom severity and treatment response in comparison to control conditions with a small effect size, on average [20]. Furthermore, Cijpers and colleagues demonstrated that self-guided psychological treatment had a small but statistically significant effect on participants with elevated levels of depressive symptomatology [17].

While there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of web-based treatments for depression, effects on health care costs have been less well researched. Only a few health economic evaluations have been reported, most focusing on guided less on unguided or minimally-guided internet interventions. Whereas most studies indicated that guided web-based interventions have the potential to be cost-effective [21], health economic evaluations of self-guided treatment programs tend to classify these interventions as not cost-effective with respect to the direct costs of health services or productivity losses [22,23,24].

Against this background, the present study was designed to examine, whether the use of the unguided-guided cognitive behavioral internet intervention deprexis over a period of 12 weeks in addition to care as usual leads to a significant reduction in direct health care costs within 12 months of observation.

Methods

Trial design

This prospective, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial compared an online intervention for depression (deprexis) to a control condition. Using an a priori generated list with random numbers, participants were randomized equally (1:1) to either a 12-week internet intervention for depression or a control arrangement (received care as usual and a brochure with general information about depressive disorders). The trial was approved by the ethics committee of the general medical council Westfalen-Lippe and the WWU Münster (Germany), and registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (identifier: DRKS00003564).

Participants

Participants were recruited from a large co-operating sickness fund between February 2010 and May 2014. All insured persons with a confirmed diagnosis of a mild (F32.0) or moderate (F32.1) depressive episode, according to the German version of the International Classification of Diseases, were invited to participate in the trial. To be included, participants had to be at least 18 years old, insured with the co-operating sickness fund for not less than 1 year, to suffer from at least mild depressive symptoms, defined by scores of > 4 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), had to have internet access, and had to be able to communicate in German. Participants with suicidality (PHQ-9: item 9 > 0) were excluded from the study prior to inclusion. Written informed consent of the study procedure, the aims of the trial and the benefits and risks of participation was obtained from all participants online prior to baseline assessment.

Interventions

Following a ‘routine care’ research approach (pragmatic RCT), all participants in the trial were permitted to use any form of treatment, including psychotherapy and antidepressant medication. In addition to care as usual, participants of the intervention group received 12-week access to the internet intervention program deprexis. This program consists of ten modules covering a variety of therapeutic content based on cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques such as problem solving, psycho-education, interpersonal skills of mindfulness and acceptance, plus one introductory and one summary module. All modules are supported by illustrations, audio recordings, or short summary sheets. The program is interactive in nature by engaging its users in exercises and by continuously asking for responses within simulated dialogues in order to tailor subsequent content [25]. It is recommended that one to two sessions of around 30 min per week are undertaken, whereby the duration of use can vary individually [26]. The intervention can be used with or without guidance by a clinician. We used an unguided program version in this trial. A detailed description of the program is given by Meyer et al. [25].

Participants in the control group received care as usual as well as an additional digital brochure with general information on depressive disorders and services for people seeking (self-)help.

Assessments

The primary outcome measure was the costs of statutory health insurance. Health care costs were estimated using health insurers’ administrative data. Cost categories included were medication costs, expenditures for inpatient hospital treatment and for rehabilitation as well as sickness benefits. All costs incurred were taken into account, not only those caused by depression. To ascertain changes in outcomes over time, health care costs were assessed for two time periods: 1 year pre enrollment to the trial and 1 year post enrollment.

The economic evaluation was conducted from a payer perspective according to the methods set out in the German recommendations on health economic evaluation [27]. Thus, indirect costs due to absenteeism or presenteeism, patients’ time and travelling costs, were excluded from the analysis. Program costs were also excluded from the analysis, as these are negotiated individually with clients such as health insurance companies and vary depending on usage circumstances [26]. Information on the amount of the fee is kept secret for competitive reasons and therefore not available for the German health care market. The costs of a single license for private persons (access to the program for 90 days after initial registration) amount to €297.50 including value-added tax [28]. Providing framework contracts with health insurance companies, the program-fees from the payer perspective can be assumed to be significantly lower than those for individuals.

Secondary outcomes were depression severity, health-related quality of life, and impairment in functioning. These outcomes were assessed retrospectively on patients’ self-report at baseline, post-treatment, three-months’ and nine-months follow-up using an online-based questionnaire.

Depression severity was measured, using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a commonly used valid and reliable self-rating inventory for assessing depression diagnoses and monitoring depression severity [29, 30]. PHQ-9 consists of nine items, reflecting the criteria of depression in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Scores range from 0 to 27 points, with a score between 5 and 9 indicating mildly depressive symptoms and scores between 10 and 14 indicating moderate depression [30, 31].

Health-related quality (HRQoL) of life was assessed simultaneously utilizing the Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12) and the EuroQol questionnaire (EQ-5D-3 L). Both instruments are widely used generic quality of life measures that have been applied in many different settings [32]. EQ-5D-3 L is a standardized instrument for describing and valuing health, consisting of a visual analog scale and a descriptive system which defines health across five dimensions (e.g. mobility, self-care or anxiety/depression), with each dimension specifying three levels of severity. By applying preference-based weights, each health state can be converted into a single summary index. Within this trial only the descriptive system was applied [32].

The SF-12 questionnaire is a reliable and sensitive instrument for measuring HRQoL in people with mental illness, consisting of 12 questions assessing the presence and severity of different aspects of functioning and limitations due to emotional or physical health problems. It can be reported as a physical or a mental component summary scale [33,34,35]. Due to its good to excellent internal consistency and convergent validity it is comparable to its longer version, the SF-36, and is therefore the instrument of choice in longitudinal studies [36].

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) is a simple and short measure of self-reported functional impairment. Psychometric properties, validity and sensitivity to change of the five item-scale have been documented in several studies, including those focusing on the treatment of depression and mental distress [37, 38]. Participants with a score below 10 can be classified as unimpaired in functioning, a score between 10 and 20 is associated with a significant functional impairment and a score above 20 suggests a moderately severe or worse psychopathology [37].

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on an expected difference between the intervention and the control group on the main outcome variable “total costs of statutory health insurance” 12 months after enrollment on the trial. Based on an estimated reduction in total health care expenditure of 20%, a power of 0.80, an alpha level of 0.05 and a drop-out rate of 30%, 1750 participants were needed in each condition. The effect-size calculation was based on an analysis of claims data from the co-operating sickness fund for 2008 and 2009, considering costs for inpatient hospital treatment, outpatient medical care, outpatient paramedical services, rehabilitation, medication costs and sickness benefits.

Data analysis

To assess the comparability between the study groups at baseline we calculated measures of central tendency and measures of variability. To determine the precision of mean values, 95%-confidence intervals were calculated. Chi-square tests and ANOVAs with Tukey’s post hoc test were applied for further examination of group differences.

To check whether the intervention also had an influence on costs independently from baseline costs, we conducted a difference in differences analysis. Hence, the difference in costs between baseline and the study period was calculated. The changes in mean costs were then examined for differences between study groups, using t-tests for independent samples (two-tailed). All costs are presented as mean, 5% trimmed mean, and 95%-CI of the mean for the year previous to study enrollment and for the study year. Furthermore, corresponding p-values are presented.

To describe the assessed secondary outcomes over time and to check the observed values for regularities, time series analyses were conducted. Comparative subgroup-analyses were applied for each of the secondary outcomes using a two-factor mixed-design ANOVA with observed means of the secondary outcomes as the within-subjects factor and the study group as between-subject-factor. To correct for violations of sphericity, the Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment was used when appropriate.

Effect sizes for the secondary outcomes are presented as Cohen’s d, which was calculated as difference between means of intervention and control group, divided by the pooled standard deviation of both groups. Following current standards, all effect sizes were calculated from the observed means of the study groups and defined as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5) and large (d = 0.8) [39, 40].

The statistical analyses were based on all observed data. We did not impute missing values as the statistical methods utilized were robust and valid for missing-at-random data and complete case analysis remains a very common case of handling missing data [41].

We performed our statistical analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 23.0. Review and preparation of claims data was carried out with Microsoft Excel 2016. The final cost variables were then reimported to IBM SPSS-statistics for further analyses.

Results

Participant flow and baseline characteristics

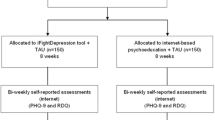

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 7644 applicants signed up for the study and were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. 3811 did not meet the inclusion criteria and thus had to be excluded from the trial. Most common exclusion criteria were the presence of suicidal feelings (53.19%; n = 2027), no insurance affiliation at the co-operating sickness fund (24.5%; n = 933) and a PHQ-9 score > 5 (11.2%; n = 426). Later, 28 participants were excluded from the analyses, because they gained multiple access to the study by applying several times using different pseudonyms. Finally, 3805 participants were randomized to either intervention (n = 1904) or control (n = 1901). The last 9-months follow-up assessment was performed in May 2014, by which time 62.24% (n = 1185) of the intervention group and 59.54% (n = 1132) of the control group had completed all questionnaires. No significant differences in rates of attrition were found between the study groups at post-treatment, three-months or nine-months follow-up. Neither randomization group, nor baseline costs, sex, age, educational status or family status were significantly associated with dropout status. Full information on participant flow is shown on the CONSORT flow chart (Fig. 1).

Participants in the intervention group did not significantly differ from those in the control group at baseline on any of the demographic variables or treatment history, indicating that randomization had been well balanced (see Table 1). Briefly, the modal participant was 46 years old, female, had completed middle secondary education (10 years of school, until age 16/17), was employed full-time, suffered from moderate self-reported depressive symptoms (PHQ-9: 12), and reported being in treatment for depression (especially drug therapy).

Health care expenditures

There were no significant differences in direct health care costs between the study conditions at baseline. During the study period total costs of statutory health insurance decreased in both groups, but changes from baseline differed significantly between the groups (tdf = 3803 = 2.05; P = .04; see Table 2). While total costs decreased by 32% from €3143 per year at baseline to €2122 in the study year in the intervention group (tdf = 1903 = 5.47; P < .001), these costs decreased by 13% in the control group (from €3131 to €2695; tdf = 1900 = 2.02; P = .04). The significant difference in total expenditure changes could mainly be attributed to a bigger decrease of sickness benefits in the intervention group (intervention: - €518 vs. control: - €293), and an opposite trend in the development of costs for inpatient hospital treatment. Whereas mean costs for inpatient treatments decreased in the intervention group by €182, they increased slightly in the control group (+€24).

However, on closer examination of sector-specific health care costs, the internet intervention did not have a significant effect on changes in single cost-categories. Medication costs and expenditures for sickness benefits decreased significantly within both study groups, but changes did not significantly differ between groups – neither for medication costs (tdf = 3803 = 1.48; P = .14), nor for sickness benefits (tdf = 3803 = 1.40; P = .16), costs of inpatient hospital treatment (tdf = 3803 = 1.14; P = .25) or rehabilitation tdf = 3803 = 0.60; P = .54).

Psychopathology and functional impairment

Based on mixed-design ANOVAs of the intention to treat sample, the intervention had a significant effect on depression severity, functional impairment, and HRQoL (whether assessed with the SF-12 mental summary scale, or with EQ-5D-3 L). In comparison to the control group, the intervention group showed a significantly greater reduction in PHQ-9 (F2.81, 5602.08 = 41.7; P < .001), a significantly greater decrease of impairment in functioning (F2.77, 5518.60 = 18.64; P < .001) and a significantly greater increase in HRQoL when assessed on the SF-12 mental health summary scale (F2.92, 5819.66 = 26.34; P < .001) and on EQ-5D-3 L (F2.97,6115.28 = 4.97; P = .002).

Across all secondary outcomes the intervention group showed a significantly greater improvement in measured effects at post-treatment assessment than the control group. While effects on the self-rating tools were relatively stable at follow-ups within the intervention group, the values of the control group were slowly approaching those of the intervention group. For detailed information on changes of secondary outcome measures see Fig. 2.

Even though the interaction between time and treatment group reached significance for all secondary outcomes, the between-group effect sizes differed from the small to medium range. Effect sizes for PHQ-9 and the SF-12 mental summary scale were larger than those for the other measures with d = 0.37 for PHQ-9 and d = 0.33 for SF-12 at post-assessment and analogously d = 0.23 and d = 0.22 at three-months’ follow-up. For SF-12 physical summary scale, EQ-5D-3 L and WSAS only small effect sizes could be determined (see Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1 (online supplementary)).

Discussion

Main results

This randomized controlled trial evaluated the potential of an innovative internet intervention program to reduce health care costs within 1 year of after starting the program use. The trial showed that the internet intervention deprexis had a significant effect on the direct costs of health care-utilization, and on measures of depression severity, HRQoL and functional impairment.

During the observation period the total costs of statutory health insurance decreased in both study groups, but changes from baseline did significantly differ between groups. While costs decreased by 32% (€1021) in the intervention group, costs decreased by 13% (€436) in the control group. As mentioned above, program costs were excluded from the analysis, as no price information is available for the German healthcare market (see 2.4). Additional scenario analyses have shown that the difference in total health care costs remains significant up to an amount of €34 per patient. If the fee exceeds an amount of €34, there would be no significant difference in total costs of statutory health insurance between intervention group and control group.

In addition to the effects on costs, the intervention was also showed to be effective in reducing disease-related secondary symptoms. In comparison to the control group, the intervention group gained from a significantly greater improvement of depressive symptoms, a significantly greater decrease of impairment in functioning a significantly greater increase in HRQoL. It is not conclusively proven whether the measured changes in secondary outcomes also represent a minimally important difference (MID). To the best of our knowledge, there is no secured evidence on the MID of the used instruments specifically for patients with depression. As the changes on PHQ-9 and WSAS reached the instruments defined cut-off-points within the intervention group, it can be assumed, that the changes in depression severity (measured with the PHQ-9) and in impairment in functioning seem to be clinically relevant.

In summary, the results on cost differences and effects point in the same direction and do not lead to different conclusions, indicating that the findings of our study are robust.

Strengths and limitations

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the trial results. First, the effect of the online therapy deprexis in gaining savings in health care costs from the payer perspective may have been underestimated, since outpatient health care cost were not available for the analysis. In particular, mild to moderate depressive disorders are commonly treated within the outpatient health care sector. Since the results of this study demonstrated significant differences in the change of total health care costs between the intervention and control group even though outpatient treatment costs were not available for the analyses, it can be assumed that the inclusion of outpatient treatment costs would reinforce the results. Recently published results from another randomized controlled trial on deprexis confirm this assumption. The study by Gräfe et al. suggest that the use of deprexis in combination with care as usual leads to a significant decrease in outpatient treatment costs, especially in those related to different types of psychotherapeutic treatment [42].

In addition to the outpatient treatment costs, the intervention costs could also not be included to the analysis. As described in the method section, program costs are negotiated individually with clients such as health insurance companies and vary depending on usage circumstances. Depending on the license-fees, the statistically significant difference in mean total costs at 12 months post-enrollment could be offset (see also section “main results”).

Another limitation exists with respect to the relatively high attrition rate at nine-months follow up. Only around half of those who had completed the baseline questionnaire and were enrolled to the study also completed the last follow-up questionnaire. Nevertheless, the study results can be assumed to be robust as neither randomization group, nor baseline costs, sex, age, educational status or family status were significantly associated with dropout status. Attrition rates at post treatment and at three-months follow-up are in line with previous trials of this intervention [43,44,45,46].

A final limitation that should be noted is the restricted transferability in terms of sociodemographic aspects. In comparison to the corresponding German general population, participants in our study had a higher educational level and women were overrepresented in the study. These findings are in line with previously published studies [47]. Thus, the higher proportion of women can be explained by a higher prevalence of depression in females. Furthermore, women are more likely to seek help than men. The higher educational level of participants within this trial could be explained by a higher demand for internet interventions by such people, which was shown for users of a web-based computer-tailored intervention promoting heart-healthy behaviors [48].

Along with the limitations mentioned above, our study also benefits from some important strengths. First, this trial used health insurers’ administrative data to estimate direct health care costs. The majority of currently published studies evaluating different e-mental health interventions and calculating their cost-effectiveness have been based on patients’ self-reports. Even though patient self-report questionnaires are a common and approved method to obtain costing data, they suffer from limitations due to recall bias, especially if recall-periods are long. In consequence, results may have been distorted by over- or underreporting [49]. As different studies have demonstrated, administrative data and self-report data provide different estimates of health-related resource-use, and of resulting costs. Particularly among people with mental disorders the discrepancy can be large [50, 51]. Since health-insurers’ administrative data are not biased due to memory failure and are based on expenses incurred, high reliability of results can be assumed.

In comparison to other recently published studies, this study also benefits from the large number of participants enrolled in the trial. To our knowledge, the present health economic evaluation is the largest published study, which was conducted alongside a randomized controlled trial focusing on costs and effects web-based treatment for depression [21]. Furthermore, our study profits from being specially powered to detect differences in costs. Hence, the power calculation for this trial was therefore based on expected savings in health care cost from the payer perspective, and not on an expected clinical outcome as in most other studies within this context.

Conclusion

This study underlines the potential of innovative e-mental-health programs in treating depressive disorders. The results suggest that the use of deprexis over a period of 12 weeks in comparison to care as usual leads to a significant reduction in costs of statutory health insurance with a simultaneous reduction of depressive symptoms, an increase in health-related quality of life and a decrease of impairment in functioning. From a health-economic perspective, the use of the program can be recommended, as cost-savings from the payer perspective are in line with the clinical benefits gained.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings are not publicly available, as the publication of the collected primary data is not covered by the informed consent.

Change history

30 July 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- EQ-5D-3 L:

-

EuroQol questionnaire

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Items

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SF-12:

-

Short Form Health Survey-12

References

GBE-Bund: Krankheitskosten. [http://www.gbe-bund.de/oowa921-install/servlet/oowa/aw92/dboowasys921.xwdevkit/xwd_init?gbe.isgbetol/xs_start_neu/&p_aid=i&p_aid=62622391&nummer=63&p_sprache=D&p_indsp=-&p_aid=46786904]. [Last accessed 16 Feb 2020].

Busch MA, Maske UE, Ryl L, Schlack R, Hapke U. Prävalenz von depressiver Symptomatik und diagnostizierter Depression bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5–6):733–9.

Klesse C, Bermejo I, Härter M. Neue Versorgungsmodelle in der Depressionsbehandlung. Nervenarzt. 2007;78(Suppl 3):585–94 quiz 595.

Pietsch B, Härter M, Nolting A, Nocon M, Kulig M, Gruber S, Rüther A, Siering U, Perleth M. Verbesserte Versorgungsorientierung am Beispiel Depression - Ergebnisse aus dem Pilotprojekt des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses (G-BA). In: Gerste B, Robra B-P, Günster C, Klauber J, Schmacke N, editors. Versorgungs-Report 2013/2014. Schwerpunkt: Depression - Mit Online-Zugang zum Internet-Portal, vol. 2014. Stuttgart: Schattauer GmbH. p. 55–75. www.versorgungs-report-online.de.

Müters S, Hoebel J, Lange C. Diagnose Depression: Unterschiede bei Frauen und Männern. GBE kompakt. 2013;4(2):1–10.

Wittchen H-U. Depressive Erkrankungen. Berlin: Robert-Koch-Inst; 2010.

Wagner CJ, Dintsios CM, Metzger FG, L'Hoest H, Marschall U, Stollenwerk B, Stock S. Longterm persistence and nonrecurrence of depression treatment in Germany. A four-year retrospective follow-up using linked claims data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27(2):e1607.

Jacobi F, Klose M, Wittchen H-U. Psychische Störungen in der deutschen Allgemeinbevölkerung. Inanspruchnahme von Gesundheitsleistungen und Ausfalltage. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz. 2004;47(8):736–44.

Knieps F, Pfaff H, editors. Gesundheit und Arbeit. Zahlen, Daten, Fakten ; mit Gastbeiträgen aus Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis. Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2016.

Friemel S, Bernert S, Angermeyer MC, König H-H. Die direkten Kosten von depressiven Erkrankungen in Deutschland -- Ergebnisse aus dem European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) Projekt. Psychiatr Prax. 2005;32(3):113–21.

Salize HJ, Stamm K, Schubert M, Bergmann F, Härter M, Berger M, Gaebel W, Schneider F. Behandlungskosten von Patienten mit Depressionsdiagnose in haus- und fachärztlicher Versorgung in Deutschland. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31(3):147–56.

Dintsios C-M, Wagner CJ. Letter to the editor of the journal of affective disorders. Supporting the guideline's quest for real direct costs of depression care. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:101–2.

Wagner CJ, Metzger FG, Sievers C, Marschall U, L'Hoest H, Stollenwerk B, Stock S. Depression-related treatment and costs in Germany. Do they change with comorbidity? A claims data analysis. J Affective Disord. 2016;193:257–66.

Statistisches Bundesamt: Krankheitskosten. Deutschland, Jahre, Krankheitsdiagnosen (ICD-10). [https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online;jsessionid=6107D1CD35C7658B3D2AFF7932F33DAE.tomcat_GO_1_3?operation=previous&levelindex=2&levelid=1506025077390&step=2]. [Last Accessed 03 May 2017].

Pieper L, Schulz H, Klotsche J, Eichler T, Wittchen H-U. Depression als komorbide Störung in der primärärztlichen Versorgung. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz. 2008;51(4):411–21.

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–66.

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R, Mohr DC, van Straten A, Andersson G. Self-guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms. A meta-analysis. PloS one. 2011;6(6):e21274.

Ebert DD, Erbe D, Berking M. Rief: Internetbasierte psychologische Interventionen (PSYNDEXshort). In: Berking M, Rief W, editors. Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie für Bachelor. Band II: Therapieverfahren Lesen, Hören, Lernen im Web. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. p. 131–40.

Laux G. Online−/Internet-Programme zur Psychotherapie bei Depression eine Zwischenbilanz. J Neurol Neurochir Psychiatr. 2017;18(1):16–24.

Karyotaki E, Riper H, Twisk J, Hoogendoorn A, Kleiboer A, Mira A, Mackinnon A, Meyer B, Botella C, Littlewood E, Andersson G, Christensen H, Klein JP, Schröder J, Bretón-López J, Scheider J, Griffiths K, Farrer L, Huibers MJH, Phillips R, Gilbody S, Moritz S, Berger T, Pop V, Spek V, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms. A meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(4):351–9.

Paganini S, Teigelkötter W, Buntrock C, Baumeister H. Economic evaluations of internet- and mobile-based interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression. A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:733–55.

Bolier L, Majo C, Smit F, Westerhof GJ, Haverman M, Walburg JA, Riper H, Bohlmeijer E. Cost-effectiveness of online positive psychology. Randomized controlled trial. J Posit Psychol. 2014;9(5):460–71.

Gerhards SAH, Graaf LE d, Jacobs LE, Severens JL, Huibers MJH, Arntz A, Riper H. Widdershoven G, Metsemakers JFM, Evers SMAA: economic evaluation of online computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy without support for depression in primary care. Randomised trial. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2010;196(4):310–8.

Phillips R, Schneider J, Molosankwe I, Leese M, Foroushani PS, Grime P, McCrone P, Morriss R, Thornicroft G. Randomized controlled trial of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy for depressive symptoms. Effectiveness and costs of a workplace intervention. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):741–52.

Meyer B, Berger T, Caspar F, Beevers CG, Andersson G, Weiss M. Effectiveness of a novel integrative online treatment for depression (Deprexis). Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(2):e15.

Twomey C, O'Reilly G, Meyer B. Effectiveness of an individually-tailored computerised CBT programme (Deprexis) for depression. A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:371–7.

von der Schulenburg J-M G, Greiner W, Jost F, Klusen N, Kubin M, Leidl R, Mittendorf T, Rebscher H, Schöffski O, Vauth C, Volmer T, Wahler S, Wasem J, Weber C. Deutsche Empfehlungen zur gesundheitsökonomischen Evaluation - dritte und aktualisierte Fassung des Hannoveraner Konsens. Gesundh ökon Qual manag. 2007;12(5):285–90.

SERVIER Deutschland GmbH: deprexis 24 - Ihr Online-Therapieprogramm bei Depressionen. [https://deprexis24-shop.servier.de/]. [Last Accessed 25 Jun 2018].

Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales. A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, Buxton M, Dolan P, Kind P, Krabbe P, Ohinmaa A, Parkin D, Roset M, Sintonen H, Tsuchiya A, Charro F d. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4(3):222–31.

Melville MR. Quality of life assessment using the short form 12 questionnaire is as reliable and sensitive as the short form 36 in distinguishing symptom severity in myocardial infarction survivors. Heart. 2003;89(12):1445–6.

Salyers MP, Bosworth HB, Swanson JW, Lamb-Pagone J, Osher FC. Reliability and validity of the SF-12 health survey among people with severe mental illness. Med Care. 2000;38(11):1141–50.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey. Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, Stradling J. A shorter form health survey. Can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med. 1997;19(2):179–86.

Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale. A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British J Psychiat. 2002;180:461–4.

Pedersen G, Kvarstein EH, Wilberg T. The work and social adjustment scale. Psychometric properties and validity among males and females, and outpatients with and without personality disorders. Personal Ment Health. 2017;11(4):215–28.

Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J Graduate Med Educ. 2012;4(3):279–82.

Leppink J, O'Sullivan P, Winston K. Effect size - large, medium, and small. Perspectives Med Educ. 2016;5(6):347–9.

Bell ML, Fiero M, Horton NJ, Hsu C-H. Handling missing data in RCTs; a review of the top medical journals. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:118.

Gräfe V, Berger T, Hautzinger M, Hohagen F, Lutz W, Meyer B, Moritz S, Rose M, Schröder J, Späth C, Klein JP, Greiner W. Health economic evaluation of a web-based intervention for depression. The EVIDENT-trial, a randomized controlled study. Health Econ Rev. 2019;9(1):16.

Klein JP, Berger T, Schröder J, Späth C, Meyer B, Caspar F, Lutz W, Arndt A, Greiner W, Gräfe V, Hautzinger M, Fuhr K, Rose M, Nolte S, Löwe B, Anderssoni G, Vettorazzi E, Moritz S, Hohagen F. Effects of a psychological internet intervention in the treatment of mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Results of the EVIDENT study, a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(4):218–28.

Berger T, Hämmerli K, Gubser N, Andersson G, Caspar F. Internet-based treatment of depression. A randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(4):251–66.

Moritz S, Schilling L, Hauschildt M, Schröder J, Treszl A. A randomized controlled trial of internet-based therapy in depression. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(7–8):513–21.

Meyer B, Bierbrodt J, Schröder J, Berger T, Beevers CG, Weiss M, Jacob G, Späth C, Andersson G, Lutz W, Hautzinger M, Löwe B, Rose M, Hohagen F, Caspar F, Greiner W, Moritz S, Klein JP. Effects of an internet intervention (Deprexis) on severe depression symptoms. Randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2015;2(1):48–59.

Späth C, Hapke U, Maske U, Schröder J, Moritz S, Berger T, Meyer B, Rose M, Nolte S, Klein JP. Characteristics of participants in a randomized trial of an internet intervention for depression (EVIDENT) in comparison to a national sample (DEGS1). Internet Interv. 2017;9:46–50.

Brouwer W, Oenema A, Raat H, Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, de Vries NK, Brug J. Characteristics of visitors and revisitors to an internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle intervention implemented for use by the general public. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(4):585–95.

Leggett LE, Khadaroo RG, Holroyd-Leduc J, Lorenzetti DL, Hanson H, Wagg A, Padwal R, Clement F. Measuring resource utilization. A systematic review of validated self-reported questionnaires. Medicine. 2016;95(10):e2759.

Palin JL, Goldner EM, Koehoorn M, Hertzman C. Primary mental health care visits in self-reported data versus provincial administrative records. Health Rep. 2011;22(2):41–7.

Goossens ME, Mölken MP-v, Vlaeyen JW, van der Linden SM. The cost diary. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(7):688–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank GAIA AG (Hamburg, Germany), which gave technical support and made the Internet intervention (deprexis) available at no cost to the participants in the trial.

We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University.

Funding

This study was funded by the DAK Gesundheit. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The results of the present manuscript are based on a large study conducted by the Bielefeld University (Department of Health Economics and Health Care Management). Steffen Moritz supported the study team during the planning process (sample size calculation and randomization). Viola Gräfe collected the data, performed the data analyses and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors provided their intellectual inputs. Viola Gräfe edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial was approved by the ethics committee of the general medical council Westfalen-Lippe and the WWU Münster (Germany), and registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (identifier: DRKS00003564).

Written informed consent of the study procedure, the aims of the trial and the benefits and risks of participation was obtained from all participants online prior to baseline assessment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the authors reported an error in their paper after publication that the supplementary table was captured as Table 3 while Table 3 was used as the supplementary file.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Secondary outcomes by study condition and time.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gräfe, V., Moritz, S. & Greiner, W. Health economic evaluation of an internet intervention for depression (deprexis), a randomized controlled trial. Health Econ Rev 10, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-020-00273-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-020-00273-0