Abstract

Background

Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is a rare but potentially life-threatening disease that causes conduction disturbance, systolic dysfunction, and, most notably, sudden cardiac death. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) plays important roles not only in diagnosing CS but also in evaluating the effects of anti-inflammatory therapy. A volume-based analysis of parameters measured by FDG PET, so-called cardiac metabolic volume (CMV), has emerged as a new assessment tool. CMV is measured as the volume within the boundary determined by a reference tissue such as the liver and the blood pool uptake. However, there is a possibility that oral steroid therapy could lead to variations of the liver and the blood pool uptake. Here, we attempted to evaluate the steroid effects on the liver and the blood pool uptake.

A total of 38 CS patients who underwent FDG PET/CT before and during steroid therapy were retrospectively enrolled. Volumes of interest (VOIs) were placed in the right lobe of the liver and descending aorta (DA). The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), SUVmean, and SUVpeak of the liver and DA were compared between time points before and during steroid therapy.

Results

The SUVmax, SUVmean, and SUVpeak of the liver during steroid therapy significantly increased from the time point before the therapy (SUVmax 3.5 ± 0.4 vs. 3.8 ± 0.6, p = 0.014; SUVmean 2.7 ± 0.3 vs. 3.0 ± 0.5, p = 0.0065; SUVpeak 3.0 ± 0.4 vs. 3.4 ± 0.6, p = 0.006). However, the SUVmax, SUVmean, and SUVpeak in the DA did not significantly change (SUVmax 2.2 ± 0.3 vs. 2.2 ± 0.4, p = 0.46; SUVmean 1.9 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.4, p = 0.56; SUVpeak 2.0 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3, p = 0.70).

Conclusions

We measured FDG uptake in the liver and blood pool before and during steroid therapy. Steroid therapy increased the liver uptake but not the blood pool uptake. Our findings suggested that the DA uptake is a more suitable threshold than liver uptake to evaluate therapeutic effects using volume-based analysis of cardiac FDG PET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease pathologically characterized by non-caseating granuloma [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) occasionally causes cardiac death via congestive heart failure, ventricular tachyarrhythmia, and advanced conduction disturbance [1,2,3,4,5]. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is widely used as a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer to assess malignant and active inflammatory diseases. The main advantage of FDG PET is its ability to visualize metabolic activity to complement anatomic imaging [6, 7]. Previous studies have demonstrated the usefulness of FDG PET in diagnosing CS and monitoring treatment response [1,2,3].

In the context of FDG PET, SUVmax reflects only the value of a single voxel and does not reflect the metabolism of the entire target lesion. Volume-based parameters such as cardiac metabolic volume (CMV) or cardiac metabolic activity (CMA) have emerged as a novel measure, mainly for assessing the metabolism of CS [6, 8, 9]. CMV was defined as the volume of the cardiac FDG accumulation within a given boundary determined using a threshold such as the liver uptake, the blood pool SUV, and the fixed value of SUV [9,10,11].

Oral steroid therapy is the mainstay among treatment options for CS [1, 3]; however, the effect of steroids on background FDG uptake such as that of the liver and blood pool has never been evaluated. The aims of this study were (1) to assess any changes of FDG uptake in the liver and blood pool from time points before and during steroid therapy; (2) to examine the relationships between these reference uptakes and laboratory data such as fasting blood sugar (FBS), aspartate amino transferase (AST), alanine amino transferase (ALT), and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (γ-GTP); and (3) to evaluate the association between the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) and the reference FDG uptakes.

Methods

Study patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hokkaido University Hospital. Electronic medical records were reviewed to obtain laboratory test results. Between January 2010 and July 2017, 238 consecutive patients received an FDG PET/computed tomography (CT) scan for suspected or diagnosed CS. Patients with no abnormal FDG uptake in the heart (n = 153), patients with insufficient clinical evidence for medical intervention (n = 16), patients with abnormal FDG activity in the heart but who had started oral steroid treatment prior to the first PET scan (n = 8), patients who had not yet received a second PET scan (n = 4), patients who showed diffuse uptake in the liver (n = 4), and patients who were not treated with steroid therapy due to either mild symptoms (n = 3), initiation of steroid therapy in another hospital (n = 3), rejection of steroid therapy (n = 1), or diagnosis with malignant lymphoma (n = 1) were excluded. Seven patients were excluded simply because medical records were not available. Finally, 38 CS patients were included in the study. Laboratory testing was performed within an interval of less than 2 weeks of the PET scanning.

Diagnosis

All patients met the widely accepted diagnostic criteria established by the Japanese Society of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (JSSOG) criteria or Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) consensus (Table 1) [12]. Diagnoses of CS were based on a combination of cardiac studies (electrocardiogram and cardiac ultrasound) and positive findings of FDG PET/CT with or without radiological studies including cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and technetium-99m (99mTc) myocardial perfusion imaging.

FDG PET/CT imaging acquisition

FDG PET/CT data were acquired using a Biograph 64 True Point PET scanner with TrueV (Siemens Healthcare, Tokyo). Each patient fasted for at least 18 h before imaging. FBS levels were checked before the FDG injection. Approximately 4.5 MBq/kg of FDG was intravenously administrated under a resting condition. A static PET scan was performed 60 min after the administration of FDG. Intravenous preadministration of UFH was applied in the 25 patients at both the initial scan and the second scan: 5 patients only at the initial scan and 2 patients only at the second scan. Six patients did not receive a UFH injection at any scan.

The acquired datasets were corrected for attenuation by low-dose CT images and were reconstructed using a point-spread function-based iterative algorithm (TrueX; Siemens) with two iterations per 21 subsets, a matrix size of 168 × 168, a voxel size of 4.1 × 4.1 × 2.0 mm, and a Gaussian filter at 4.0 mm full width at half maximum. The transaxial and axial fields of view were 58.5 cm and 21.6 cm, respectively.

Imaging analysis

We measured the SUVs in the liver by two methods as previously proposed: (1) a manual method with a 3-cm-diameter spherical VOI placed on the normal inferior right lobe (RL) of the liver [7] and (2) an automated method for objectively defining the liver VOI in FDG PET/CT [9]. With this automated method, the SUVmean and its standard deviation (SD) inside the VOI were used to determine the threshold value as follows: threshold = SUVmean + 3 × SD. SUVmax, SUVmean, and SUVpeak were estimated to compare the uptake before steroid therapy with that during the therapy. SUVpeak was defined as the average activity concentration within a 1-cm3 spherical VOI centered on the SUVmax voxel. The mean value of the Hounsfield units derived from CT was obtained using the same VOI. For the blood pool SUV, a 1-cm-diameter spherical VOI was set in the descending aorta (DA) so as not to overlap with the blood vessel wall as previously reported [13].

Correlations between the FDG uptake and the preparation protocols

Our institute introduced dietary instructions using low-carbohydrate diet (LCHD) in 2010 to acquire sufficient suppression of physiological FDG uptake in the heart. Briefly, LCHD does not include bread or rice but include a boiled egg, tofu, and grilled chicken [4]. In this study, 23 patients were hospitalized and consumed a dinner < 5 g of carbohydrate the evening prior to FDG-PET scan. Fifteen patients were hospitalized and consumed a dinner not modified. Our institute stopped applying UFH before FDG injections in 2016, because it was deemed that UFH loading might suppress myocardial physiological uptake in patients with suspected CS while providing no extra diagnostic value compared with extended fasting [14]. As a result, our study included patients with different pre-scan protocols. (1) We compared the liver and DA uptakes between those with and without UFH administration to confirm the effect of UFH and, in addition, (2) we compared the liver and DA uptakes between patients with and without LCHD before FDG PET scans.

Correlations between the liver uptake and clinical factors

Laboratory data such as serum AST, ALT, and γ-GTP, which are markers for liver dysfunction, were compared to the FDG uptake and Hounsfield units of the liver.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Pairwise comparisons were performed with a paired t test. p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical calculations were carried out using SAS (JMP ver. 13; SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Multiple regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the effect of UFH on the liver and blood pool uptakes on the basis of patient factors, steroid therapy, and administrated UFH.

Results

We identified 38 patients (61.4 ± 9.6 years old, 5 males) who presented with abnormal myocardial FDG uptake due to active CS out of a group of 238 consecutive patients. The clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 2. Four patients were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). FBS before FDG injection was < 150 mg/dl for all patients, in both PET scans. None of the patients were rescheduled for the follow-up owing to a high BS level. The time span between the two scans and the amount of oral steroids at the second scan were 61.5 ± 23.5 days and 26.8 ± 4.3 mg/day, respectively.

Differences in liver FDG uptake between pre- and mid-steroid therapies

Compared with the pre-steroid therapy scan, the liver thresholds during steroid therapy significantly increased in both the manual method (SUVmax 3.5 ± 0.4 vs. 3.8 ± 0.6, p = 0.014; SUVmean 2.7 ± 0.3 vs. 3.0 ± 0.5, p = 0.0065; SUVpeak 3.0 ± 0.4 vs. 3.4 ± 0.6, p = 0.0061) and the semi-automated method (SUVmean + 3SD; 3.5 ± 0.4 vs. 3.8 ± 0.6, p = 0.015).

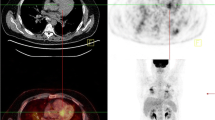

A typical case whose liver uptake was significantly increased during the oral steroid therapy is shown in Fig. 1.

A representative case before and during the oral steroid therapy of CS. 18F-FDG PET/CT images obtained before (a, b) and during (c, d) treatment of CS. Note the profound decline in the myocardial uptake and increase in the liver uptake. The threshold increased from the time point before (a, 3.7) to that during steroid therapy (c, 4.5). The SUV of the DA showed little change from the time point before (b, SUVmax 2.9; SUVmean 2.6) to that during steroid therapy (d, SUVmax 2.8; SUVmean 2.5)

Differences in blood pool FDG uptakes between pre- and mid-steroid therapies

There were no significant differences in the SUVmax (2.2 ± 0.3 vs. 2.2 ± 0.4, p = 0.46), SUVmean (1.9 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.4, p = 0.56), or SUVpeak (2.0 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3, p = 0.70) of the DA between the pre- and during-steroid therapy scans (Table 3). The SUV values assessed by the manual process in the DA did not show an association with the administrated UFH (Table 3).

Correlations between the FDG uptake and the preparation protocols

Before steroid therapy, 30 patients received UFH before FDG injection, whereas the remaining 8 patients did not. During steroid therapy, 27 patients received UFH before FDG injection, whereas the remaining 11 did not. The semi-automated thresholds of the liver were not associated with the use of UFH in patients before steroid therapy (Table 4). The SUVs in the liver during steroid therapy were significantly higher in patients in whom UFH was administrated (Table 4). However, multiple regression analysis showed no effect of UFH on the liver and blood pool uptakes. Both patient factors and steroid therapy had significant effects on the liver uptake (SUVmean + 3SD patient factor: p = 0.002, steroid therapy: p = 0.001, UFH: p = 0.54; SUVmax patient factor: p = 0.06, steroid therapy: p = 0.04, UFH: p = 0.46; SUVmean patient factor: p = 0.03, steroid therapy: p = 0.002, UFH: p = 0.75; SUVpeak patient factor: p = 0.02, steroid therapy: p = 0.001, UFH: p = 0.43). Only patient factor had significant effects on the blood pool uptake (SUVmax patient factor: p < 0.0001, steroid therapy: p = 0.07, UFH: p = 0.54; SUVmean patient factor: p < 0.0001, steroid therapy: p = 0.25, UFH: p = 0.36; SUVpeak patient factor: p < 0.0001, steroid therapy: p = 0.34, UFH: p = 0.88) (Table 5). Among 38 patients, 23 consumed LCHD in the evening both before and during steroid therapy, and the remaining 15 did not. Even when we divided the patients into those with and without LCHD, steroid therapy increased the liver uptake but not the blood pool uptake (Table 6).

Correlations between liver uptake and each of the clinical factors and Hounsfield units

Compared to the values before steroid therapy, the FBS and serum ALT during steroid therapy were significantly higher. However, there were no significant differences in AST or γ-GTP between the initial and second scans (Table 7). Also, the mean values of Hounsfield units (HUs) were not significantly different between the two scans (49.9 ± 8.3 HU vs. 52.1 ± 6.8 HU, p = 0.22).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the effect of steroid therapy on FDG uptake of the liver and DA by comparing PET images taken before and during steroid therapy. We assessed both the manual and automated methods of liver uptake analysis because several methods to set the VOI in the liver were reported. Wahl et al. proposed a manual method to set VOI on the normal inferior right lobe (RL) which is a widely used method in accordance with the Positron Emission Tomography Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST) criteria [7]. Hirata et al. proposed an automated method to set the VOI in the liver, which was not always in the inferior RL, with very high inter-operator reproducibility [9]. Similar results were obtained by both methods.

The SUVs obtained from the liver during steroid therapy were significantly higher than those of the pre-therapy scan, whereas the SUVs from DA were not altered by steroid therapy.

CS is increasingly recognized as a cause of heart failure and arrhythmias. FDG PET is a promising tool to assess the activity of CS. The volume-based assessment of FDG uptake is a more precise predictor of cardiac events than SUVmax [1, 8]. An appropriate SUV threshold is important for the identification of the precise CMV. This study is the first to assess the effects of steroid therapy on the FDG thresholds used to estimate the metabolic volume.

CMV is defined as the volume within a given boundary determined using the FDG uptake threshold, such as the liver uptake and the blood pool [8, 10]. However, as our study suggested, the liver uptake in CS patients was significantly increased from the time point before to that during steroid therapy. Glucocorticoids promote changes in body composition that correlate with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and eventual onset of hyperglycemia [15,16,17]. Steroid-induced diabetes mellitus (SIDM) has been recognized as a complication of steroid use. The effect of glucocorticoids on glucose metabolism is likely the result of impairment of multiple pathways including sensitivity to glucose and the ability to release insulin due to the beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in other tissues [17]. One of the etiologies of SIDM is based on the effect of glyceroneogenesis in the liver and adipose tissue [18]. In the adipose tissue, glyceroneogenesis controls the rate of free fatty acid (FFA) release in the blood. On the other hand, glyceroneogenesis is responsible for the synthesis of triacylglycerol (TAG) from FFA and glycerol 3-phosphate (G-3-P) in the liver [18]. The regulation of this process in both the liver and adipose tissue occurs via the enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK). In patients using glucocorticosteroids, PEPCK gene expression in adipose tissue is suppressed, inhibiting glyceroneogenesis [19].

Because FDG uptake increases in the presence of inflammation, the increase of liver uptake may be due to an inflammatory process caused by steroid therapy [20, 21]. In the liver, PEPCK upregulates the synthesis of TAG from FFA and G-3-P, and liver fat increases. Although the HUs on CT did not show a significant difference, the accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes was assumed to have increased. While most fatty liver diffusely involves the whole liver, focal or multi-focal fat deposition in the liver is occasionally encountered and causes a diagnostic challenge. Some regions of the liver are well known as common sites of focal fat deposition [22, 23]. A 30-mm-diameter spherical VOI cannot assess the whole liver fat content and the CT HUs can be affected by focal fat deposition. [22].

Insulin resistance might be another potential reason for the increased liver uptake during steroid administration. In the liver, PEPCK stimulates glycerol production and FFA concentrations increase in the blood. In the end, the amount of FFAs released into the blood increases and the increased FFA level interferes with glucose utilization and results in insulin resistance, especially in skeletal muscle [24]. Though the specific effect of insulin on hepatic glucose uptake remains unclear, insulin stimulates glucose uptake in the liver of both insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant subjects [25]. Iozzo et al., employing the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, confirmed that insulin increases hepatic phosphorylation of FDG to FDG-6-phosphatase (FDG-6-P) [25]. There is a strong evidence to suggest that hepatic steatosis and insulin resistances are driven by obesity-induced adipokines, and the association between insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis has been established [26, 27].

Although serum ALT levels are often used as a surrogate marker for liver inflammation, ALT is typically elevated in only 50% of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cases [20, 28]. In our patients, neither AST nor γ-GTP levels showed a statistically significant difference between time points before and during steroid therapy. Our results thus suggested that ALT alone was a poor marker for the presence of hepatic steatosis. Previous studies reported that patients with advanced fibrosis had significantly lower ALT levels than those with no/mild fibrosis and that ALT had no role in identifying patients with advanced disease [29, 30].

Our results showed that oral steroid therapy and individual patient factors showed significant effect on the blood pool and liver uptakes and UFH administration before FDG injection did not affect the liver or blood pool SUV [14]. UFH increases plasma FFA levels due to activation of lipoprotein and hepatic lipases [4]. As mentioned above, increased FFA interferes with glucose utilization and results in insulin resistance [24]. However, preadministration of UFH is just before FDG injection and the assessment of effect on liver uptake is difficult.

Oral steroid therapy showed no effect on the SUV obtained from the blood pool. Our group previously reported that individual FDG uptake thresholds from the DA were preferable to those from the liver, due to the high inter-operator reliability and non-dependence on dietary relations [13]. Our present findings show further evidence that the threshold for the evaluation of a therapy response should be determined by DA rather than liver values.

Limitations

This study had some methodological limitations. First, the study was retrospective from a single center and the sample size was relatively small, partly because the study focus was patients with active cardiac sarcoidosis. Second, while all patients in our study underwent PET imaging, other tests, such as Holter monitoring and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were not routinely performed. Third, four patients with T2DM, who might have higher liver fat content compared with healthy subjects, were included in this study [26]. Fourth, we measured CT HUs using non-diagnostic low-dose CT as a tool of attenuation correction in PET/CT imaging. Compared to unenhanced diagnostic CT, a low-dose CT scan can be reliably used to exclude NAFLD, if neither liver attenuation of < 40 HU nor a liver-to-spleen ratio < 1.1 is present [31]. However, chemical shift images on MRI are desirable for the diagnosis of diffuse hepatic steatosis because they can demonstrate suppression of the signal from mixtures of microscopic lipids and water at the cellular level [20, 22]. Finally, we assessed the liver and the blood pool FDG uptake in patients using medium-dose steroids (29.7 ± 1.6 mg/day of prednisolone) but did not investigate whether the dose of the steroid affected the results. Oral steroid treatment for CS is generally initiated with 30 mg and is tapered down to 15–25 mg in most patients by the 3-month follow-up visit [1]. Further assessment of patients with tapered-down steroid use is warranted.

Conclusions

We conducted a quantitative analysis of the liver and blood pool FDG uptake in patients diagnosed with CS. The liver FDG uptake was shown to significantly increase during steroid therapy. Thus, individual FDG uptake thresholds to assess the metabolic volume difference between time points before and during steroid therapy should be determined from the DA rather than liver uptake. Our results suggested that the DA is a more suitable threshold than liver uptake to evaluate cardiac metabolic volume.

References

Ishiyama M, Soine LA, Vesselle HJ. Semi-quantitative metabolic values on FDG PET/CT including extracardiac sites of disease as a predictor of treatment course in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2017;7:67.

Mostard RL, Van Kuijk SM, Verschakelen JA, et al. A predictive tool for an effective use of F18-FDG PET in assessing activity of sarcoidosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:57.

Mostard RL, Voo S, van Kroonenburgh MJ, et al. Inflammatory activity assessment by F18 FDG-PET/CT in persistent symptomatic sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105:1917–24.

Ohira H, Tsujino I, Yoshinaga K. (1)(8)F-Fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1773–83.

Blankstein R, Osborne M, Naya M, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:329–36.

Manabe O, Ohira H, Yoshinaga K, Naya M, Oyama-Manabe N, Tamaki N. Qualitative and quantitative assessments of cardiac sarcoidosis using 18F-FDG PET. Ann Nucl Cardiol. 2017;3:117–20.

Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122S–50S.

Ahmadian A, Brogan A, Berman J, et al. Quantitative interpretation of FDG PET/CT with myocardial perfusion imaging increases diagnostic information in the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:925–39.

Hirata K, Kobayashi K, Wong KP, et al. A semi-automated technique determining the liver standardized uptake value reference for tumor delineation in FDG PET-CT. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105682.

Blomberg BA, Bashyam A, Ramachandran A, et al. Quantifying [(1)(8)F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the arterial wall: the effects of dual time-point imaging and partial volume effect correction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1414–22.

Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Ohira H, et al. The effects of 18-h fasting with low-carbohydrate diet preparation on suppressed physiological myocardial (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and possible minimal effects of unfractionated heparin use in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23:244–52.

Ishida Y, Yoshinaga K, Miyagawa M, et al. Recommendations for (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for cardiac sarcoidosis: Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology recommendations. Ann Nucl Med. 2014;28:393–403.

Manabe O, Kroenke M, Aikawa T, et al. Volume-based glucose metabolic analysis of FDG PET/CT: The optimum threshold and conditions to suppress physiological myocardial uptake. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-017-1122-6.

Gormsen LC, Christensen NL, Bendstrup E, Tolbod LP, Nielsen SS. Complete somatostatin-induced insulin suppression combined with heparin loading does not significantly suppress myocardial 18F-FDG uptake in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:1108–15.

Siddiqui A, Madhu SV, Sharma SB, Desai NG. Endocrine stress responses and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Stress. 2015;18:498–506.

Burke SJ, Batdorf HM, Eder AE, et al. Oral corticosterone administration reduces insulitis but promotes insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in male nonobese diabetic mice. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:614–26.

Hwang JL, Weiss RE. Steroid-induced diabetes: a clinical and molecular approach to understanding and treatment. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30:96–102.

Cadoudal T, Leroyer S, Reis AF, et al. Proposed involvement of adipocyte glyceroneogenesis and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in the metabolic syndrome. Biochimie. 2005;87:27–32.

Taybi T, Nimmo HG, Borland AM. Expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase kinase genes. Implications for genotypic capacity and phenotypic plasticity in the expression of crassulacean acid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:587–98.

Bural GG, Torigian DA, Burke A, et al. Quantitative assessment of the hepatic metabolic volume product in patients with diffuse hepatic steatosis and normal controls through use of FDG-PET and MR imaging: a novel concept. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:233–9.

Borra R, Lautamaki R, Parkkola R, et al. Inverse association between liver fat content and hepatic glucose uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57:1445–51.

Jang JK, Jang HJ, Kim JS, Kim TK. Focal fat deposition in the liver: diagnostic challenges on imaging. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42:1667–78.

Yoshikawa J, Matsui O, Takashima T, et al. Focal fatty change of the liver adjacent to the falciform ligament: CT and sonographic findings in five surgically confirmed cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(3):491–4.

Cadoudal T, Blouin JM, Collinet M, et al. Acute and selective regulation of glyceroneogenesis and cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in adipose tissue by thiazolidinediones in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:666–75.

Iozzo P, Geisler F, Oikonen V, et al. Insulin stimulates liver glucose uptake in humans: an 18F-FDG PET study. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(5):682–9.

Keramida G, Hunter J, Peters AM. Hepatic glucose utilisation in hepatic steatosis and obesity. Biosci Rep. 2016;36(6).

Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1494–505.

Burke A, Lucey MR. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:686–93.

Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57:1441–7.

McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59:1265–9.

Ahmed AM, Ebid ME, Ajlan AM, Al-Mallah MH. Low-dose attenuation correction in diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42:2454–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eriko Suzuki for her support of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SF collected and analyzed data and contributed to the manuscript preparation. OM designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. KH provided a semi-automated technique and contributed to the design of the study. HO, TA, MN, IT, and KK conducted examinations and patient follow-up. TA, NO-NM, and TS critically contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures in studies involving humans were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Institutional Review Board of Hokkaido University Hospital is the local ethics committee that reviewed and approved the protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Furuya, S., Manabe, O., Ohira, H. et al. Which is the proper reference tissue for measuring the change in FDG PET metabolic volume of cardiac sarcoidosis before and after steroid therapy?. EJNMMI Res 8, 94 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-018-0447-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-018-0447-8