Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent adult stem cells. MSCs and their potential for use in regenerative medicine have been investigated extensively. Recently, the mechanisms by which MSCs detect mechanical stimuli have been described in detail. As in other cell types, both mechanosensitive channels, such as transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7), and the cytoskeleton, including actin and actomyosin, have been implicated in mechanosensation in MSCs. This review will focus on discussing the precise role of TRPM7 and the cytoskeleton in mechanosensation in MSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

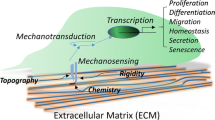

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been explored extensively in regenerative medicine due to their potential for differentiation into multiple tissue types. Recent studies have shown that both chemical and mechanical signals within the microenvironment direct MSC differentiation [1]. Mechanisms of MSC mechanosensation have been described. Putative mediators of MSC mechanosensation include transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7), a mechanosensitive plasma membrane calcium channel, and the cytoskeleton [2–6]. Calcium mobilization has been well defined as a regulator of gene expression and cell behavior [7]. Both TRPM7 and the cytoskeleton were reported to be essential for mechanical stimulus-induced Ca2+ mobilization [2, 6] and subsequent differentiation [2, 5, 8]. The precise role of each subcellular component in mechanosensation and Ca2+ mobilization is, nevertheless, incompletely understood. In this article, we will focus on discussing current understanding of the membrane mechanosensitive channel and the cytoskeleton in the process of mechanosensation in MSCs.

Mechanosensitive channels in MSCs

Mechanosensitive channels are widely reported as sensors of mechanical stimulation in multiple cell types, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and myocardial cells. Transient receptor potential (TRP), a calcium channel, including TRPV1, TRPV4, and TRPA1, are known to be involved in sensory signal transduction in a variety of species from C. elegans to higher vertebrates [9, 10]. In MSCs, there is accumulating evidence that mechanical stimulation regulates MSC behavior via Ca2+ mobilization [5]. We have characterized membrane TRPM7 in human bone marrow-derived MSCs serving as a mechanosensor and conducting calcium influx, which induced osteogenesis [2]. Adjacent to our work, two additional groups also implicated membrane TRPM7 in MSC Ca2+ influx in response to shear stress and stretch [5, 6].

With mechanical stimuli, such as pressure, patch-clamp pipette suction, and patch-clamp pipette stretch, membrane TRPM7 opens and conducts Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. Likewise, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) inositol trisphosphate receptor type 2 (IP3R2) Ca2+ release is also triggered by TRPM7 activation, which amplifies Ca2+ signaling. This increase in intracellular Ca2+ activates a downstream transcription factor, such as NFATc1, to induce osteogenesis [2]. TRPM7 activation appears to be independent of the cytoskeleton since disruption of actin polymerization by cytochalasin D does not abolish suction-induced TRPM7 activation [2]. Furthermore, membrane TRPM7 remains reactive to pipette suction in the absence of the cytoplasm as evidenced by patch clamp inside-out record model data [2]. TRPM7-regulated intracellular Ca2+ release, however, appears to be dependent upon inositol trisphosphate (IP3) since inhibition of cytophospholipase C (PLC), which hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce IP3 upon interaction with TRPM7, abolished TRPM7-triggered ER Ca2+ release [2]. This model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Two different models of the transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) mediation of mechanical stimulation in MSCs. Left: The bilayer lipid model. When mechanical stimulus is applied to the plasma membrane, TRPM7 is activated by membrane tension conducting Ca2+ influx. At the same time, cytophospholipase C (PLC) is activated and may hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce inositol trisphosphate (IP3) which subsequently activates inositol trisphosphate receptor type 2 (IP 3 R2) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) conducting Ca2+ release. Right: The cytoskeleton tether model. When mechanical stimulus is applied to the cytoskeleton, it transmits stress that activates TRPM7-conducting Ca2+ influx, followed by activation of ER-conducting Ca2+ release. The exact linkage mechanism between TRPM7 and ER IP3Rs is still unknown. With mechanical stimulation, transcription factors like NFATc1 translocate to the nucleus and promote the osteogenic gene expression. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMP), Diacylglycerols (DAG), Fibronectin (Fn)

There are two general models that explain channel gating by mechanical stimuli. The bilayer lipid model proposes that force is delivered to the channel by surface tension or bending of the lipid bilayer causing a hydrophobic mismatch that favors channel opening. The tether model proposes that specific accessory proteins such as intracellular cytoskeletal elements or extracellular matrix molecules bind to channel proteins and transmit mechanical stimuli to the channel protein resulting in a channel conformational change and opening [10]. The data discussed above belong to the bilayer lipid model.

The role of the cytoskeleton in mechanosensation in MSCs

The cortical cytoskeleton structurally supports the fluid bilayer which provides the cell membrane with shear rigidity, preserves cell deformability, and allows dramatic changes in cell shape and size. The actin cytoskeleton is a highly dynamic network which senses mechanical stimuli, remodels its own microstructures, and activates associated signaling pathways [11, 12].

In MSCs, actin skeleton, vinculin, and primary cilia are involved in mechanosensation [3, 4, 8, 13]. Primary cilia are made by the cytoskeleton component microtube and vinculin is a membrane-cytoskeletal protein in focal adhesion plaques that is involved in linkage of integrin adhesion molecules to the actin cytoskeleton. Both primary cilia and vinculin are co-localized with TRPM7 or other TRP channels. Kuo et al. reported that F-actin reorganizes in parallel with oscillatory shear stress and directs MSC differentiation by regulating β-catenin [3]. They propose that β-catenin coupling with integrin and cadherin on the membrane forms complexes with actin filaments, and that F-actin depolymerization releases these proteins to either activate downstream signaling pathways or be degraded. A study by Kim et al. further clarified the role of the cytoskeleton by directly applying stretch to integrin via fibronectin-coated beads and laser-tweezer [6]. Due to membrane reservoir compensation and direct linkage of integrin to actin, this model applies stimulus directly to the cytoskeleton rather than the plasma membrane [14, 15]. With this stimulus, membrane TRPM7 quickly activated and conducted extracellular Ca2+ influx (around 20 s after stimulation) faster than ER Ca2+ release (around 100 s after stimulation) [6]. Disruption of cytoskeletal actin by cytochalasin D, disruption of microtubules by nocodazole, or knockdown TRPM7 expression eliminated the force-induced Ca2+ oscillations. They found both activation of TRPM7 and ER Ca2+ release is dependent on the cytoskeleton (Fig. 1), while ER Ca2+ release upon mechanical stimulation was also depend on actomyosin contraction [6]. These results indicate that the cytoskeleton also directs response to mechanical stimulus, and that it can deliver mechanical force to membrane channels such as TRPM7 and the ER Ca2+ release channel.

The coordinated cooperation of subcellular components in mechanosensation

According to current evidence, the membrane TRPM7 channel can be activated by either lipid bilayer tension or tethered cytoskeleton-transmitted mechanical stress to trigger ER IP3Rs Ca2+ release. Mechanosensation is a well-orchestrated process of three steps: mechanical transmission, signal activation, and signal amplification. When mechanical stimulus is applied to the plasma membrane or cytoskeleton, the lipid bilayer or cytoskeleton transmits the mechanical force to the mechanically gated Ca2+ channel TRPM7, resulting in Ca2+ influx. TRPM7 activation also triggers ER IP3R2 Ca2+ release via PLC-derived IP3 [2] or, potentially, by other mechanisms [6]. During this process, the transmission apparatus (lipid bilayer or cytoskeleton) triggers signal effector (mechanosensitive channel TRPM7) and signal amplifiers (ER IP3Rs), which work together as a system to transfer mechanical signals into biological responses. ’The data discussed above suggest that MSCs are unable to respond to mechanical stimulation in the absence of these elements.

Conclusion

TRPM7 appears to play an important role in mechanosensation in MSCs. Since the transmission apparatus can be lipid bilayer or cytoskeleton. And the linkage between TRPM7 and ER IP3Rs can be PLC or another unknown mechanism. But the TRPM7 is indispensable for mechanical stimulus-activated Ca2+ influx and ER Ca2+ release and its downstream biological effects [2, 5, 6].

Abbreviations

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- IP3:

-

Inositol trisphosphate

- IP3R2:

-

Inositol trisphosphate receptor type 2

- MSC:

-

Mesenchymal stem cell

- PIP2:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PLC:

-

Cytophospholipase C

- TRP:

-

Transient receptor potential

- TRPM7:

-

Transient receptor potential melastatin 7

References

Huebsch N, Lippens E, Lee K, Mehta M, Koshy ST, Darnell MC, Desai RM, Madl CM, Xu M, Zhao X, et al. Matrix elasticity of void-forming hydrogels controls transplanted-stem-cell-mediated bone formation. Nat Mater. 2015;14(12):1269–77.

Xiao E, Yang HQ, Gan YH, Duan DH, He LH, Guo Y, Wang SQ, Zhang Y. Brief reports: TRPM7 senses mechanical stimulation inducing osteogenesis in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(2):615–21.

Kuo YC, Chang TH, Hsu WT, Zhou J, Lee HH, Hui-Chun Ho J, Chien S, Kuang-Sheng O. Oscillatory shear stress mediates directional reorganization of actin cytoskeleton and alters differentiation propensity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(2):429–42.

Hoey DA, Tormey S, Ramcharan S, O’Brien FJ, Jacobs CR. Primary cilia-mediated mechanotransduction in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(11):2561–70.

Liu YS, Liu YA, Huang CJ, Yen MH, Tseng CT, Chien S, Lee OK. Mechanosensitive TRPM7 mediates shear stress and modulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells through Osterix pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16522.

Kim TJ, Joo C, Seong J, Vafabakhsh R, Botvinick EL, Berns MW, Palmer AE, Wang N, Ha T, Jakobsson E, et al. Distinct mechanisms regulating mechanical force-induced Ca(2)(+) signals at the plasma membrane and the ER in human MSCs. eLife. 2015;4, e04876.

Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386(6627):855–8.

Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126(4):677–89.

Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426(6966):517–24.

Christensen AP, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(7):510–21.

Ehrlicher AJ, Nakamura F, Hartwig JH, Weitz DA, Stossel TP. Mechanical strain in actin networks regulates FilGAP and integrin binding to filamin A. Nature. 2011;478(7368):260–3.

Chowdhury F, Na S, Li D, Poh YC, Tanaka TS, Wang F, Wang N. Material properties of the cell dictate stress-induced spreading and differentiation in embryonic stem cells. Nat Mater. 2010;9(1):82–8.

Holle AW, Tang X, Vijayraghavan D, Vincent LG, Fuhrmann A, Choi YS, del Alamo JC, Engler AJ. In situ mechanotransduction via vinculin regulates stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2013;31(11):2467–77.

Gauthier NC, Masters TA, Sheetz MP. Mechanical feedback between membrane tension and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(10):527–35.

Maniotis AJ, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(3):849–54.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on research partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81500819).

Authors’ contributions

EX and CC contributed to conception, and drafted the manuscript. YZ contributed to conception and design, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, E., Chen, C. & Zhang, Y. The mechanosensor of mesenchymal stem cells: mechanosensitive channel or cytoskeleton?. Stem Cell Res Ther 7, 140 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0397-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0397-x