Abstract

Background

Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors are rare. If tumor growth is extraluminal and involves the head of the pancreas, the diagnosis of a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor is difficult.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old Japanese woman was referred to our hospital with anemia. An enhanced computed tomography scan showed a hypervascular mass 30 mm in diameter, but the origin of the tumor, either the duodenum or the head of the pancreas, was unclear. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed bulging accompanied by erosion and redness in part of the duodenal bulb. Mucosal biopsy was not diagnostic. Endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration was difficult to perform because a pulsating blood vessel was present in the region to be punctured. These findings led to a diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor invasion to the duodenum. The patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Histologically, the tumor was made up of spindle-shaped cells immunohistochemically positive for c-Kit and CD34. The tumor was ultimately diagnosed as a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Conclusion

Extraluminal duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors are rare and mimic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration is useful for preoperative diagnosis, but it is not possible in some cases. Intraoperative diagnosis based on a completely resected specimen of the tumor may be useful for modifying the surgical technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (dGISTs) are extremely rare, and account for < 5% of all gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) cases [1, 2]. A biopsy is considered essential for the diagnosis of GIST, but endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) may not be possible in some situations. dGISTs may develop extramurally, extensively, in a stem-like fashion, or may be embedded in the pancreatic parenchyma, complicating the distinction from duodenal or pancreatic primary hypervascularized enhancing tumors on computed tomography (CT) and the selection of the appropriate surgical technique. We present a case of pancreaticoduodenectomy for a dGIST that was difficult to differentiate from a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET).

Case presentation

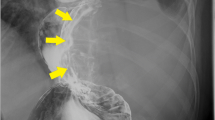

A 44-year-old Japanese woman had anemia identified by a medical examination in the workplace. Six months later, she was hospitalized with lightheadedness. Laboratory data revealed a hemoglobin level of 4.1 g/dL. She was admitted to our hospital after receiving a transfusion and ferrotherapy. Results of all other laboratory studies were within the normal range (Table 1). She had no pregnancies or children. Her father had died of pancreatic cancer. She had no significant past medical history and no smoking history, and she did not consume alcohol. On admission, her heart rate was 60 beats per minute, her blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg, and her temperature was 37.1 °C. There were no other findings on physical and neurological examination. Contrast-enhanced CT showed a 30-mm mass that was heterogeneously enhanced at the margins, and the origin of the tumor, either the duodenum or the head of the pancreas, was unclear (Fig. 1a, b). Positron emission tomography (PET) showed a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 16.7 in the tumor (Fig. 2a, b). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed bulging accompanied by erosion and redness in part of the duodenal bulb (Fig. 3a). A mucosal biopsy was not diagnostic. EUS demonstrated a 40 × 35 mm2 mass with cystic and solid components in the head of the pancreas (Fig. 3b). EUS-FNA was difficult to perform because a pulsating blood vessel was present in the region to be punctured (Fig. 3c). These findings led to the diagnosis of pNET invasion to the duodenum. The patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Macroscopic findings were a 4.0 × 2.3 × 3.9 cm3 mass that occupied the first part of the duodenum, that broke down on the mucosal surface to form an ulcer, and that developed extrusive growth toward the pancreatic head (Fig. 4). Microscopic findings were that the tumor was made up of spindle-shaped cells, including nine mitotic figures per 50 high-power fields, immunohistochemically positive for c-Kit and CD34 (Fig. 5). The tumor was diagnosed as a high-risk dGIST on the basis of the Fletcher classification or modified Fletcher classification. The patient was treated with adjuvant imatinib, and she has not developed a recurrence over a 2-year period.

a Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealing bulging accompanied by erosion and redness in part of the duodenal bulb. b EUS demonstrating a 40 × 35 mm2 mass with cystic and solid components in the head of the pancreas. c EUS fine-needle aspiration (FNA) considered, but was difficult to perform, because of a pulsating blood vessel present in the region to be punctured

Microscopic findings included the tumor being made up of spindle-shaped cells, including nine mitotic figures per 50 high-power fields, immunohistochemically positive for vimentin, C-kit, and DOG-1. The tumor was diagnosed as a high risk dGIST on the basis of the Fletcher classification or the modified Fletcher classification

Discussion

In this case, a hypervascularized tumor in the pancreatic head region was discovered owing to anemia, but biopsy was difficult, and a pancreaticoduodenectomy with lymph node dissection was performed on the basis of suspicion of pNET on CT. Postoperative pathological examination revealed a primary dGIST, and radical surgery with partial resection could be considered.

GISTs are relatively common mesenchymal tumors that occur predominantly in the stomach (60–70%) and small intestine (25–35%) [3]. dGISTs are rare lesions, constituting 30% of primary duodenal tumors and less than 5% of all GISTs [4]. On CT, dGISTs appear as heterogeneously enhanced hypervascularized masses [5, 6]. When extraluminal dGIST growth extends to the head of the pancreas, the tumor is difficult to differentiate from other well-vascularized tumors. pNETs appear as circumscribed solid masses that displace surrounding structures and are often hyperattenuating on arterial and venous phase images [7]. Since dGISTs and pNETs may have similar features on imaging, these two lesions may be misdiagnosed. After searching the PubMed database with the search terms “duodenal GIST” and “pancreas tumor,” we found 13 cases of dGIST that were difficult to differentiate from pancreatic tumors preoperatively, including our case [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. In four cases, EUS-FNA was performed, three of which were diagnosed as GIST [10, 14, 15, 17]. EUS-FNA is the only way to obtain a preoperative pathological diagnosis. Generally, the specificity of EUS-FNA is reported to be 100%, and the sensitivity is 84% [20,21,22]. However, the rate of adverse events related to the EUS-FNA procedure is reportedly 0.98–3.4%, with events including acute pancreatitis, bleeding, infection, and duodenal perforation [23,24,25,26]. Among the previous reports, 6 of the 13 cases had symptoms associated with gastrointestinal bleeding [8, 11, 13, 18]. These included the cases for which EUS-FNA was not performed because of concerns about possible recurrent bleeding [8], and surgery was performed immediately after blood transfusion [19].

In our case, the tumor contained a pulsatile artery, and the risk of bleeding from EUS-FNA was high. Popivanov et al. [27] reported 549 cases of resected dGIST, and their analysis revealed that in contrast to the other localizations, dGIST has upper gastrointestinal bleeding as the most frequent manifestation. In such cases, pancreatoduodenectomy was performed in an emergency setting due to life-threatening bleeding. For GISTs, R0 resection with 1–2 cm clear margins is a sufficient treatment, and lymph node dissection is not recommended owing to the low incidence of lymphatic metastases [28]. On the other hand, surgical resection with regional lymph node dissection is the only curative treatment for pNETs [29]. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis before surgery. There was one case report in which the diagnosis of dGIST was made from intraoperative frozen tissue [11]. Although biopsy of the intraperitoneal cavity has a high risk of peritoneal dissemination and is contraindicated, intraoperative histology was assessed after complete tumor resection in this report. This method may be useful when a change in surgical technique is considered. Yanming et al. reported that the postoperative prognosis of dGIST is promising and is affected mainly by tumor factors, and the choice of surgical approach should depend on the anatomical location and tumor size [30]. If a case shows detachment around the tumor, partial resection of the duodenum and intraoperative histological diagnosis is considered possible. In our case, the tumor was misdiagnosed as a pNET preoperatively, and the patient therefore underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy with lymph node dissection. Even if a dGIST had been diagnosed before surgery, because detachment of the boundary between the dGIST in the first portion of the duodenum and the pancreas head had a higher risk of pancreatic juice leakage and peritoneal dissemination, pancreaticoduodenectomy would have been considered appropriate. However, lymph node dissection would not have been necessary.

Conclusion

Extraluminal dGISTs are rare and mimic pNETs. EUS-FNA is useful for preoperative diagnosis, but it is not applicable in some cases. When resecting a mass in the pancreatic head region, intraoperative diagnosis based on a completely resected specimen of the tumor may be useful for modifying the surgical technique, considering the possibility of dGIST.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Agaimy A, Wunsch PH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a regular origin in the muscularis propria, but an extremely diverse gross presentation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:322–9.

Winfield RD, Hochwald SN, Vogel SB, et al. Presentation and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 2006;72:719–22.

Liu Q, Kong F, Zhou J, Dong M, Dong Q. Management of hemorrhage in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a review. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:735–43.

Buchs NC, Bucher P, Gervaz P, Ostermann S, Pugin F, Morel P. Segmental duodenectomy for gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(22):2788–92.

Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the pre-Imatinib mesylate era—a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–9.

Sawaki A. Rare gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): omentum and retroperitoneum. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:116.

Lewis RB, Lattin GE Jr, Paal E. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: radiologic clinicopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1445–64.

Futo Y, Saito S, Miyato H, et al. Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors appear similar to pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a case report. Int Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:358–61.

Bormann F, Wild W, Aksoy H, et al. A pancreatic head tumor arising as a duodenal GIST: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014: 420295.

Ueda K, Hijioka M, Lee L, et al. A synchronous pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Intern Med. 2014;53(21):2483–8.

Vasile DT, Iancu G, Iancu RC, et al. Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as pancreatic head mass—a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58(1):255–9.

Uchida H, Sasaki A, Iwaki K, et al. An extramural gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum mimicking a pancreatic head tumor. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12(4):324–7.

Aziret M, Çetinkünar S, Aktaş E, et al. Pancreatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor after upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and performance of Whipple procedure: a case report and literature review. Am J Case Rep. 2015;3(16):509–13.

Singh S, Paul S, Khandelwal P, et al. Duodenal GIST presenting as large pancreatic head mass: an uncommon presentation. JOP. 2012;13(6):696–9.

Hayashi K, Kamimura K, Hosaka K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for diagnosing a rare extraluminal duodenal gastrointestinal tumor. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9(12):583–9.

Kwon SH, Cha HJ, Jung SW, et al. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum masquerading as a pancreatic head tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(24):3396–9.

Graur F, Nechita VI, Bolboaca SD, et al. EPCephalic duodenopancreatectomy for neurofibromatosis associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. A case report. Ann Ital Chir. 2019;8:S2239253X19030482.

Cavallini C, Cecera A, Ciardi A, Caterino S, et al. Small periampullary duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated by local excision: report of a case. Tumori. 2005;91(3):264–6.

Sakakima Y, Inoue S, Fujii T, et al. Emergency pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy followed by second-stage pancreatojejunostomy for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum with an intratumoral gas figure: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34(8):701–5.

Liang X, Yu H, Zhu LH, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum: surgical management and survival results. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6000–10.

Săftoiu A, Vilmann P, Hassan H. Utility of colour Doppler endoscopic ultrasound evaluation and guided therapy of submucosal tumours of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Ultraschall Med. 2005;26:487–95.

Yamashita S, Sakamoto Y, Saiura A, et al. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Am J Surg. 2014;207:578–83.

Wang KX, Ben QW, Jin ZD, et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:283–90.

Katanuma A, Maguchi H, Yane K, et al. Factors predictive of adverse events associated with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic solid lesions. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2093–9.

Yoon WJ, Daglilar ES, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Mino-Kenudson M, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Peritoneal seeding in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas patients who underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: the PIPE Study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:382–7.

Tsutsumi H, Hara K, Mizuno N, et al. Clinical impact of preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:94–100.

Popivanov G, Tabakov M, Mantese G, Cirocchi R, Piccinini I, D’Andrea V, Covarelli P, Boselli C, Barberini F, Tabola R, Pietro U, Cavaliere D. Surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum: a literature review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:71.

Joo MK, Park JJ, Kim H, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical resection of GI stromal tumors in the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:318–26.

Ohmoto A, Rokutan H, Yachida S. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: basic biology, current treatment strategies and prospects for the future. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(1):143.

Zhou Y, Wang X, Si X, et al. Surgery for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pancreaticoduodenectomy versus local resection. Asian J Surg. 2020;43(1):1–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MI wrote the manuscript. MI and IO designed the study. AW, RK, RK, HS, KM, MI, KT, SS, and TT proofread the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Inoue, M., Ohmori, I., Watanabe, A. et al. A duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor mimicking a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: a case report. J Med Case Reports 16, 308 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03468-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03468-7