Abstract

Background

DYRK1A maps to the Down syndrome critical region at 21q22. Mutations in this kinase-encoding gene have been reported to cause microcephaly associated with either intellectual disability or autism in humans. Intellectual disability accompanied by microcephaly was recapitulated in a murine model by overexpressing Dyrk1a which mimicked Down syndrome phenotypes. However, given embryonic lethality in homozygous knockout (KO) mice, no murine model studies could present sufficient evidence to link Dyrk1a dysfunction with autism. To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying microcephaly and autism spectrum disorders (ASD), we established an in vivo dyrk1aa KO model using zebrafish.

Methods

We identified a patient with a mutation in the DYRK1A gene using microarray analysis. Circumventing the barrier of murine model studies, we generated a dyrk1aa KO zebrafish using transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN)-mediated genome editing. For social behavioral tests, we have established a social interaction test, shoaling assay, and group behavior assay. For molecular analysis, we examined the neuronal activity in specific brain regions of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish through in situ hybridization with various probes including c-fos and crh which are the molecular markers for stress response.

Results

Microarray detected an intragenic microdeletion of DYRK1A in an individual with microcephaly and autism. From behavioral tests of social interaction and group behavior, dyrk1aa KO zebrafish exhibited social impairments that reproduce human phenotypes of autism in a vertebrate animal model. Social impairment in dyrk1aa KO zebrafish was further confirmed by molecular analysis of c-fos and crh expression. Transcriptional expression of c-fos and crh was lower than that of wild type fish in specific hypothalamic regions, suggesting that KO fish brains are less activated by social context.

Conclusions

In this study, we established a zebrafish model to validate a candidate gene for autism in a vertebrate animal. These results illustrate the functional deficiency of DYRK1A as an underlying disease mechanism for autism. We also propose simple social behavioral assays as a tool for the broader study of autism candidate genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

ASD is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of neurodevelopmental disorders representing various subtypes of altered social communication, unusually restricted interests, or repetitive behavior [1]. Next-generation sequencing approaches have identified additional nonsense, frameshift, and insertion/deletion mutations in ASD or intellectual disability cases [2,3,4].

In humans, DYRK1A is located on chromosome 21q22.13 in the “Down Syndrome Critical Region (DSCR)” at 21q22.1–q22.3 [5]. This gene has been proposed as a major contributor to the pathogenesis of Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntington’s disease [6,7,8]. However, truncation of DYRK1A due to balanced chromosome translocations was previously reported in two unrelated individuals with overlapping phenotypes of developmental delay and microcephaly [9]. Subsequently, mutations in DYRK1A are also associated with primary microcephaly, intellectual disability, and ASD [10,11,12,13]. In this report, we describe a newly affected individual with a heterozygous 21 kb intragenic deletion which involves the last five exons of DYRK1A; the individual exhibits ASD in addition to learning difficulties and microcephaly.

Since these distinct cognitive phenotypes could arise from either increase or decrease of gene dosage, overexpression and KO techniques of DYRK1A were applied to animal models in order to elucidate the underlying mechanism. Intellectual disability coupled with microcephaly was recapitulated in a Dyrk1a overexpressing murine model which mimicked Down syndrome patients who possess an extra copy of chromosome 21 [14, 15]. Dyrk1a null mutants exhibit generalized growth delay, including an overall reduction in the size of the developing brain as well as embryonic lethality during mid-gestation [16,17,18]. Heterozygous mutants show decreased neonatal viability and reduced brain size from birth to adulthood. Neurobehavioral analysis revealed that heterozygous mutants in adulthood are deficient in motor function and learning [18,19,20]; however, none of these murine model studies present sufficient evidence to directly link Dyrk1a dysfunction with autism in the context of social interaction of an ASD animal model.

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying microcephaly and ASD, we established an in vivo KO model using zebrafish. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a tractable vertebrate model in biological research, especially in the fields of neuroscience [21, 22]. Recent scientific reports show conservation of brain structures between zebrafish and humans, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, habenula, and hypothalamus [23]. Moreover, Danio rerio displays broad complex behaviors in aspects of learning, cognition, aggression, anxiety, and social interaction [22]. The zebrafish and human genomes are well conserved with more than 80% of human disease genes represented in the zebrafish model [24]. Thus, the zebrafish is a useful tool in elucidating the function of novel genes involved in head formation or neurogenesis [25, 26] and, more recently, for validating the function of human candidate genes involved in microcephaly, intellectual disability, and ASD [27,28,29,30,31].

We employed targeted KO of the zebrafish DYRK1A orthologue and found that dyrk1aa KO zebrafish exhibits microcephaly and impaired social behavior which is a key representative feature of ASD. Also, we report on the development of two approaches in assessing behavioral phenotypes of the zebrafish ASD model. Since social behavioral analysis in the context of ASD has not been reported on any other DYRK1A animal model, we undertook the analysis of social and group behavioral interactions in the dyrk1aa KO zebrafish. Several social interaction tests have already been addressed which assess the social behavior of zebrafish [32, 33]; however, we have improved upon these social interaction assays by newly developing the shoaling bowl assay in which a flat-round bowl provides a convenient means for assessing group behavior in zebrafish autism models.

Methods

Clinical report

The proband was noted as being small for gestational age according to regular ultrasound scans. The affected female of northern European ancestry, now age 11 and half years, was born at 37-week gestation by emergency Cesarean section due to a drop in heart rate. Her birth weight was 1.9 kg. Due to breathing problems around the time of birth, the subject required suction at birth and did not cry. Afterward, she was administered oxygen and housed in the Special Care Baby Unit. The subject had a computed tomography (CT) brain scan at 1 year 3 months which showed mild cerebral atrophy involving mainly the frontal lobes. At age 3 years 1 month, she had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and microcephaly was noted. Her head circumference has always been at − 5 standard deviations being below the 0.4th percentile. Her MRI showed increased X-ray CLC spaces which is a reflection of a moderate degree of cerebral volume loss, more so in the white matter than in gray. There were also some abnormal subcortical high signals in both temporal lobes; however, no overlaying abnormality was present. Also, there was evidence of thinning in the corpus callosum as well as a degree of volume loss in the medulla oblongata compared to previous scans. In addition, a mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles probably represented white matter loss. There was a small high-signal area seen in the white matter of the right parietal lobe representing gliosis.

Developmentally, the subject could sit alone at 8 months, roll from front to back by 1 year, commando crawl at 14 months, crawl properly around 16 ½ months, pull to stand at 15 months, walk around furniture at 1 year 7 months, and walk alone at 2 years despite having immature gait. She did not require the need of walking aids, but her legs, hips, knees, and ankles have always been very stiff. The subject’s parents approached their doctor when she was 3 years 6 months old, and she was diagnosed, at 6 years of age, with scoliosis of the back, differing leg lengths, inflexibility, and possible cerebral palsy. She has not had any serious head injuries but started having seizures at about 13 months. At the age of 2 ½, she was diagnosed with epilepsy and continues to have four or five serious seizures a year; each lasts over an hour. At 9 years 6 months, she had increasing difficulty in straightening her knees completely and walking, requiring frequent use of a wheelchair. At her latest clinical assessment, she displayed an increase in tone in her upper extremities and continues to be ambulatory. Clinically, her spinal deformity has not worsened as confirmed by full spine X-rays. She has a limb length discrepancy—shorter on the left than the right—with some pelvic obliquity. She also has bilateral valgus ankle joints and recurrent chest infections.

The stiffness in her arms and wrists makes dressing and undressing difficult. She has a combination of diagnoses including global development delay, ASD, learning difficulties, and illiteracy. Also, her level of speech at 9 years 8 months of age was that of a 3- to 4-year-old and required attendance to a special school. She continues to present high levels of challenging behaviors associated with distress and anxiety, continued problems in sociability, and little interest in her peers preferring to play on her own. She does not like crowds and might kick and shout at people if they invade her personal space. While she can be clingy to her parents, she makes very little eye contact and is fixated on particular items such as footballs and goggles; the latter of which she has at least 17 pairs that she wears at home but never at the swimming pool. She flaps her hands when excited, and she continues to have problems with attention and decreased concentration.

Microarray analysis

Array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was carried out using a BlueGnome 8x60k International Standard Cytogenomic Array (ISCA) design oligonucleotide microarray. Test DNA was referenced against same-sex control DNA, and data was analyzed in BlueFuse Multi v2.2. This platform should detect the majority of copy number imbalances > 15 kb in 500 disease gene/telomeric regions and > 180 kb in the genomic backbone and may detect smaller imbalances in some instances. The derivative log ratio (DLR) quality score given for this hybridization is 0.21. Probes are mapped to GRCh37/hg19.

Generation of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish

We identified the zebrafish dyrk1aa gene and its exon/intron boundaries by searching the Ensembl database (GRCz10 Ensembl gene ID: ENSDARG00000063570; transcript ID: ENSDART00000100073). The dyrk1aa (7 bp deletion) KO fish was generated using TALEN, as previously reported [34]. A TALEN pair targeting exon 5 of dyrk1aa (left target site: 5′-tgg gtc gcc atc aag atc at-3′; right target site: 5′- gcc ttc ctg aat cag gct ca-3′) was designed and assembled by ToolGen Inc. (http://toolgen.com/). In vitro-transcribed RNA of the TALEN pair (100 ng each) was microinjected into 1~2 cell stage of fertilized zebrafish eggs, which were then grown to 4-month-old adulthood. A stable mutant line, dyrk1aakrb1, was identified and genotyped by direct PCR and sequencing performed using two sets of nested primers: the outer primer pair 5′-cca gca aca aga agg aga gg-3′ (forward) and 5′-agc cct gat ctt tcc agg tt-3′ (reverse) and the inner primer pair 5′-tta caa cga cgg cta tga cg-3′ (forward) and 5′-ttc atc tcg gtg tcg tgc t-3′ (reverse). The PCR amplification conditions were as follows: for primary PCR, 35 cycles of 95 °C, 20 s; 59 °C, 40 s; 72 °C, 1 min; and for secondary PCR, 25 cycles of 95 °C 20 s; 55 °C, 40 s; 72 °C, 30 s. The progeny were propagated through a series of out-crossings with wild type (WT) fish; these animals were eventually in-crossed to obtain homozygous KOs. The KO zebrafish line is deposited in the KCTC (http://biorp.kribb.re.kr/) with deposit number, BP1294898.

Brain histology and expression analysis

To ascertain brain histology, 7-month-old male WT and KO fish were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution overnight, then compared for body length. Among fish of the same size and age, brains were isolated and imaged and sizes were measured using ImageJ software. After dehydration in ethanol and clearing in xylene, brains were infiltrated with paraffin, embedded, and serial-sectioned. The sections (10-um thick) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The total area and ventricle area of the brain in the sections were measured using ImageJ and the ratio (ventricle area/total area ×100) was calculated. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described [35] using the following digoxigenin (DIG RNA labeling kit, Roche)-labeled antisense probes: sox2, neurog1, ccnd1, c-fos, crh, oxt, th1, vglut2.2, and gad1b. For c-fos analysis, 7-month-old male WT and KO zebrafish were fixed in 4% PFA solution immediately after social interaction test. For crh analysis, 7-month-old male WT and KO fish were fixed after social isolation. For oxt, th1, vglut2.2, and gad1b analysis, 7-month-old male WT and KO fish from their home tank were fixed. To detect cell death, 3-week-old zebrafish larvae were fixed in 4% PFA solution for 4 h at room temperature. Fixed larvae were embedded in agar-sucrose solution (1.5% agar, 5% sucrose). The agar blocks containing the larvae were sunk in 30% sucrose solution and processed for transverse cryostat serial-sectioning. The sections (25-um thick) were immuno-stained with an antibody against activated caspase-3 (BD Biosciences), which marks apoptotic cell death.

Behavioral tests for early larval zebrafish

Dark flash test

Dark flash test was performed as previously reported [36]. Free swimming 6 dpf larvae were placed in a 24-well plate (SPL life Sciences— each well contains a single larva— then inserted into the DanioVision Observation Chamber (Noldus). To induce freezing/startle response, dark flash pulses illuminated the plate for 30 s followed by lights off for 30 s (flash-off dark condition). This scheme was repeated five times. Locomotive response to visual stimuli was measured by video-tracking analysis using EthoVision XT7 software (Noldus). For analysis of locomotor activity, raw data was converted into total distance moved (cm) by each larva per 10 s time-bins. After behavioral assay, each zebrafish larva was genotyped using genomic PCR.

Sleep and waking activity

Sleep and waking activity was measured as previously described [37]. dyrk1aa KO embryos and control WT embryos were raised in a light- and temperature-controlled incubator. Five-day-old larvae were placed in a 24-well plate in the observation chamber of Danio Vision tracking system for acclimation under controlled lighting conditions (12 h–12 h light-dark cycles). Starting from 5 dpf, locomotion of each larva during day and night phases were tracked and analyzed by EthoVision XT7 software over a course of 2 days. Locomotor activity was analyzed by converting raw data into the velocity (cm/s) of each larva per 30-min time-bins.

Social and group behavior tests for adult zebrafish

Novel tank assay

Novel tank assay was performed as previously described [38]. Each 7-month-old male WT or KO zebrafish was placed in a transparent tank with dimensions measuring 24 × 15 × 15 cm. We replicated the novel tank assay with eight WT and eight KO fish. The back side of the tank was covered with a white sheet to aid data recording. We used a three-compartment novel tank with top, bottom, and middle virtual zones. All behavior tests were recorded for a period of 10 min from the lateral viewpoint of the tank using a video camera (Sony, HDR-CX190). Fish were returned to their home tanks immediately after completion of the test. The raw data was analyzed using EthoVision XT7 software.

Social interaction assay

The social interaction test was modified and improved upon from a previous study [32]. The tank was divided into two sections by placing a metal mesh or an acrylic plate separator at the first quarter of the tank. To conduct the social interaction test, the first section of the tank was designated as the social cue. The second section was used as the space to investigate the behavior of tester fish. In every experiment, we used different 7-month-old male fish for both the social cue and tester to maintain similar conditions. We replicated this experiment with 30 WT and 30 KO tester fish, in total. The second section was divided further into four equal sub-zones; the zone nearest to the social cue was designated zone “I”, the second nearest zone “II”, the third zone “III”, and the last zone “IV”. The hollow-rectangular pattern of the metal mesh separator (0.3 × 0.3 cm) created a gray shadow, while the acrylic plate was transparent. All behavioral tests were performed between 13:00 and 17:00 h using water from a tank adjusted to the holding room temperature. All experimental fish were raised in a social environment. One day prior to each test, fish were transferred to a different tank in an isolated environment. All behavioral tests were recorded from the lateral viewpoint of the tank, for a period of 15 min using a video camera.

Shoaling bowl assay

Fish form groups in a behavior called shoaling [39,40,41]. To test whether dyrk1aa KO zebrafish show altered shoaling behavior, a group of 7-month-old fish (n = 3–7 fish per group) was placed together and monitored by video tracking. We introduced a unique and simple device to test and quantify shoaling behavior. First, we examined several types of bowls (with different shapes, sizes, depths, and colors) and selected a round, flat bottom, white bowl for further experiments (upper half diameter, 33 cm; bottom diameter, 24 cm; height, 11 cm; and water depth, 3.2 cm). All tests for group behavior were recorded for a period of 15 min using a video camera at a fixed height with a top view of the bowl. The recorded videos were analyzed using 31 screenshots made every 10 s for 10–15 min measuring the distances between individual fish in the group using the ImageJ program.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, comparisons between WT and KO fish were done using a two-tailed, Student’s t test. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In all tests, p < 0.05 was considered to be significant. * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results

Intragenic microdeletion of DYRK1A in an ASD patient

Microarray analysis of a patient with ASD and microcephaly was used to detect a de novo 21 kb microdeletion at 21q22.13, arr [hg 19] (38,865,151–38,885,792)X1 dn, within the DYRK1A gene (Fig. 1).

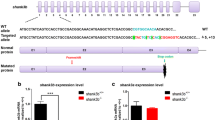

Generation of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish

To model DYRK1A dysfunction in zebrafish, we generated a loss-of-function mutant using TALEN-targeted mutagenesis [34]. Genotyping of F0 adults identified three KO zebrafish out of 65 founder fish, with a targeting efficiency of 4.6%. Finally, one stable KO was established as a dyrk1aa KO zebrafish line, called dyrk1aa krb1. This dyrk1aa KO line harbors an aberrant early stop codon due to a seven base pair (7 bp) deletion in exon 5 of dyrk1aa which likely leads to the truncation of the protein, including most of the kinase domain, and loss of function (Fig. 2a, b).

Generation of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish and microcephaly phenotype analysis. a Schematic representation of the genomic structure of dyrk1aa and a 7 bp deletion generated by gene targeting with TALEN. b Predicted structures of WT and dyrk1aa KO mutant proteins in zebrafish. The 7 bp deletion resulted in a frame-shift mutation and premature termination at the kinase domain. c, d Similar brain size in WT (c) and KO fish (d) is seen at the 2-week-old stage. Fluorescent live neurons are visible in the genetic background of HuC:eGFP transgenic zebrafish. Anterior to the left, dorsal view. Scale bars 0.2 mm. e – j Sections of a 3-week-old zebrafish head region were immuno-stained with an antibody against activated caspase-3. Coronal sections at the level of the eye: bright-field image (e, h) and fluorescent image (f, g, i, and j). g, j Magnification of inset in (f, i). Arrows indicate caspase-3 positive cells in the brain. Scale bars 0.2 mm. k The number of caspase-3 positive cells is increased in the brain of KO fish. Five animals for each WT and KO fish were used for the analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 by Student’s t test. l, m Pictures of adult WT and KO zebrafish. dyrk1aa KO zebrafish were normal in body length and overall morphology except for a reduction of brain size. Arrowheads indicate the position of the brain in the head region. Scale bars 5 mm. n, o Photograph of dissected brains from WT and KO zebrafish, showing microcephaly phenotype in KO zebrafish. Anterior olfactory bulbs were positioned at the left, ventral view. Scale bars 0.4 mm. p, q Confirmation of microcephaly phenotype in KO zebrafish by histological examination. Dashed line in n and o indicates the relative section position used in p and q. Brain sections were stained with H&E. KO zebrafish brain had wider ventricle space than WT zebrafish. Arrows point to TeV. Scale bars 0.4 mm

Characterization of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish at early larval stages

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish showed normal development of gastrulation and morphology at early stages. Since DYRK1A is known to play key roles in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation during neurogenesis in mouse models [16, 42], we tested the expression of the neural stem cell marker, sox2, and the neuronal determination marker, neurog1, by whole-mount in situ hybridization. No significant change of sox2 and neurog1 expression were found in the dyrk1aa KO embryos at early developmental stages, 24 h post-fertilization (hpf), and 48 hpf (Additional file 1: Figure S1A-D). We also examined the expression of cell cycle marker, cyclin D1 but found no detectable changes in dyrk1aa KO embryos compared to WT (Additional file 1: Figure S1E, F).

Next, we tried to identify any behavioral changes in dyrk1aa KO fish at the early larval stage, i.e., 6 days post-fertilization (dpf). Zebrafish eyes begin to detect light by 3.5 dpf, and zebrafish larvae start swimming freely at 5 dpf [36, 43]. We measured the locomotive response to visual stimuli by video-tracking analysis. At 6 dpf, both WT and dyrk1aa KO larvae showed similar patterns of response to visual stimuli (Additional file 1: Figure S1G). Also, we examined circadian rhythms of KO larvae by measuring locomotor activity under day-night cycles over a period of 2 days, between 5 and 7 dpf [37]. The zebrafish pineal gland contains a circadian oscillator which drives rhythms of melatonin synthesis and transduction mechanisms for entrainment by light cycles [44, 45]. Quantitative profiling revealed that KO larvae display similar activity during both day and night when compared to controls (Additional file 1: Figure S1H).

Adult dyrk1aa KO zebrafish display microcephaly

DYRK1A is known to be involved in brain size regulation in different model organisms, as evidenced by a small brain phenotype upon loss-of-function [18, 46]. Since dyrk1aa KO adult zebrafish were not significantly different from WT siblings when assessed for body length and overall morphology (Fig. 2l, m), we examined brain size of dyrk1aa KO fish. dyrk1aa WT and KO brains were dissected, and KO zebrafish brains were found to be significantly smaller than those of WT (Fig. 2n, o). KO zebrafish brains also had pronounced size reduction in specific brain regions, including the telencephalon (Tel), tectum opticum (TeO), and corpus cerebelli (CCe) (Additional file 2: Figure S2A). Examination of brain sections further supported our morphological analyses. In transverse sections, we found that the space of KO brain ventricles was wider than that of WT brains, especially in the tectal ventricle (TeV) (Fig. 2p, q; Additional file 2: Figure S2B). To identify an intermediate developmental time-point in which neurological phenotypes begin to occur, we assessed dyrk1aa KO fish in late larval stages. When brain sections were stained with an antibody against activated caspase-3, known to detect apoptotic cell death [47], we found an increased number of apoptotic cells in the brain of dyrk1aa KO fish at 3 weeks of age compared to that of age-matched WT fish (Fig. 2c–j). Together, these results suggest that the microcephaly phenotype may be attributed to neuronal cell death during brain development, which is consistent with data reported by previous studies [47].

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish display anxiolytic behavior in a novel tank assay

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish are viable and fertile into adulthood. To examine behavioral changes of adult dyrk1aa KO fish, we performed a novel tank assay aimed to measure anxiety. This test is based on the animal’s innate behavior to seek protection in a novel environment by freezing and reducing exploratory behavior [38]. As fish gradually adapt to a novel environment, an increase in exploration usually occurs, which is characterized by (1) increased time spent in the top of the tank, (2) increased entries to the top of the tank, and (3) decreased freezing [48,49,50]. Using a three-compartment novel tank with top, bottom, and middle zones (Fig. 3a–c), we found that KO fish spent significantly more time in the middle or top zones than in the bottom than WT fish (Fig. 3d, e; Additional file 3: Figure S3A, B). In addition, KO fish displayed less freezing time than WT fish (Additional file 3: Figure S3C); however, there were no significant differences for total distance and speed of movement in both WT and KO fish, indicating that this phenotype is not due to motor deficits (Additional file 3: Figure S3D, E). Taken together, these data suggest that dyrk1aa KO zebrafish experience less anxiety than WT fish.

Novel tank assay showing anxiolytic behavior in dyrk1aa KO zebrafish. a An illustration of a novel rectangular tank. Dashed lines indicate the boundaries of three vertically different zones (top, middle, and bottom). b, c Representative images of zebrafish behavior in the early time phase (1–5 min). dyrk1aa KO zebrafish display reduced anxiety-like phenotype, swimming more time in middle and top zones. d–f Duration per minute in each zone. Upon introduction to the novel tank, zebrafish display a preference to remain at the bottom zone. dyrk1aa KO fish spent significantly less times in this zone, compared to WT siblings. Black line for WT and gray line for dyrk1aa KO zebrafish. Number of fish used in this assay: n = 8 for WT fish, n = 8 for KO fish, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 by Student’s t test

Establishment of a social interaction assay in WT zebrafish

Social interaction is an essential behavior of zebrafish as they express strong preferences towards conspecifics [32]. We standardized the social interaction test in WT zebrafish and tested the effect of group size of the “social cue” on the behavior of a “tester” fish by increasing the number of fish in a group from one to five (Additional file 4: Figure S4). In most cases, WT tester fish showed a clear preference for the cue fish group by staying in the most proximal zone “I” for a longer period of time than in the more distant zones II, III, and IV. This tendency of social interaction increased gradually according to the group size of the social cue. However, we determined that optimal group size of the social cue was three fish under these experimental conditions. Next, we tested the effect of different separating materials on social interaction. We noted a difference of social interaction between metal mesh and acrylic plate separators (Additional file 4: Figure S4A, C) and speculated better visibility of tester fish towards the social cue with the transparent acrylic plate rather than the metal mesh accounted for the differences. Since metal mesh in the water tank has a dark-gray color (shadow-like) with hole-like patterns, we reasoned that this might interrupt tester fish perception of the social cue. Next, we established a reliable time frame for the measurement of social interaction. After video recording for 15 min, the data corresponding to different time frames were collected for every minute and analyzed. Since animals, including fish, tend to show anxiety-like behavior in new environments and require time for acclimation, we chose the 6–10 min time frame for social interaction analysis. After 10 min, the WT tester fish began to show a diminished degree of social interaction (Additional file 4: Figure S4E, F).

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish show impaired social interaction

DYRK1A has been associated with ASD in humans by previous reports [12, 13]. In our study, we tested whether the dyrk1aa KO zebrafish could be used as an animal model for the study of ASD. After 15 min of video recording (Additional file 5: Figure S5), the 6–10 min time frame (Fig. 4) was analyzed for social interaction of WT and KO tester fish. WT test fish were largely observed in the zone “I”, and minimal time was noted in other zones (Fig. 4b, d; Additional file 6: Movie S1). In contrast, dyrk1aa KO fish spent significantly less time in zone “I” and comparatively more time in the other zones than their WT counterparts (Fig. 4c, d; Additional file 7: Movie S2). In addition, the total number of transit movements between zones was analyzed to reveal further evidence of impaired social interaction of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish (Fig. 4e; Additional file 8: Fig. S6). We hypothesized that the impaired social interaction of dyrk1aa KO fish may be due, at least in part, to reduced neuronal function of the brain. To test this idea, we investigated c-fos expression, a functional marker of neuronal activation [51], and consistent with our prediction, c-fos activation was greatly reduced in the brain of KO fish compared to control WT fish. This reduction was observed in the ventral hypothalamic region (Fig. 5a–d) which is highly activated in the brain of WT zebrafish that are subjected to intense handling stress [51, 52]. Subsequently, we analyzed the expression of various neural markers (Additional file 9: Figure S7) and found a significant change in the expression of crh mRNA in a specific brain region of dyrk1aa KO fish. The WT and dyrk1aa KO fish were subjected to acute social isolation for 24 h before analysis; they had been raised in a group environment. In response to acute social isolation, expression levels of crh in KO fish brains of were found to be reduced in the preoptic area (PO, the homolog of the mammalian paraventricular nucleus) of the hypothalamus compared to WT (Fig. 5e–h) [53]. CRH encodes for the stress hormone, corticotrophin-releasing hormone, and is expressed in and secreted by neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) which links stress-related emotional responses and social interaction behaviors in mammals [54,55,56].

Social interaction assay showing impaired social behavior in dyrk1aa KO zebrafish. a Here, three fish were used as a social cue against a tester fish. Bold dashed line indicates the position of the separator in the water tank. Three narrow dashed lines indicate the boundaries of four different zones (I, II, III, and IV) in the moving space of the tester fish, ranging from the most proximal to the most distal, respectively from the social cue fish group. Arrows indicate the transition of tester fish between zones. b, c Video tracking of 5-min movements of WT or dyrk1aa KO fish, showing the social interaction with the social cue. d Duration time for tester fish in each different zone. Black bars for WT fish and white bars for KO mutant fish. e Number of transit movements of tester fish at each zone boundary; movement from “I” to “II”, “II” to “III”, and “III” to “IV” zone. Number of tester fish used in this assay: n = 30 for WT fish, n = 30 for KO fish, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 by Student’s t test

In situ hybridization of c-fos and crh in the brain of KO and WT fish. a–d Detection of c-fos mRNA expression in the dissected brain of WT (a, b) and KO (c, d) fish. Induction of strong c-fos expression is seen in specific brain regions (white asterisk) in WT fish (b) during social interaction, compared to that in KO fish (d). Higher expression of c-fos is observed in the diffuse nucleus of the inferior lobe (DIL) in the KO fish brain. fb, forebrain; mb, midbrain; hb, hindbrain; hy, hypothalamus. Ten animals for each WT and KO fish analysis were used. e–h Detection of crh expression in the brain of WT (e, f) and KO (g, h) fish. After acute social isolation for 24 h, crh-expressing cells are slightly reduced in preoptic area (PO, black asterisk) in KO fish (h), compared to that of WT fish (f). Eight animals for each WT and KO fish analysis were used. Anterior to the top and ventral view. b, d, f, and h Magnification of the ventral hypothalamic region boxed in a, c, e, and g. Scale bars 0.2 mm (a, c, e, and g), 0.76 mm (b, d), and 0.94 mm (f, h)

Additional file 6: Movie S1. WT fish in social interaction assay. The WT zebrafish shows social interaction with social cues. (AVI 1335 kb)

Additional file 7: Movie S2. KO fish in social interaction assay. The dyrk1aa KO zebrafish has no interest in social cues. (AVI 1367 kb)

Development of a novel shoaling assay in WT zebrafish

Zebrafish actively form shoals which are highly sensitive to various experimental manipulations and thus can be used to quantify social behavior [57, 58]. The distances between individual fish can reveal whether they are socially interactive or experiencing impaired social behavior among conspecifics [32, 33]. The degree of shoaling behavior, i.e., social cohesion, was presented by the mean distance (cm) between the individual fish in a group (Additional file 10: Figure S8A). We tested various shoaling experimental conditions using WT fish: differences in the size of the shoaling group (3–7 fish), water volume (1–4 l), and water depth (1.8–5.6 cm). We determined that a group of three fish and a water depth of 3.2 cm in a round bowl with a 24-cm-inside diameter were optimal conditions for the assay (Additional file 10: Figure S8B, C). Notably, the mean distance was relatively constant with an average of 5.8 cm in the WT fish groups. In addition, we observed that fish mostly moved as a group along the narrow ridge of the round bowl (Fig. 6b–f). Since the shape of this small ridge (4-cm width and 3.2-cm depth with curve) looks similar to that of the natural “shoal”, e.g., in stream, we called this area a “mini shoal”.

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish show impaired social behavior in the shoaling assay. a Schematic description of the “mini shoal” formed at the ridge of water body in a flat and round bowl. b–f Snapshots of shoaling behavior in a group of WT fish, ranging from three to seven fish/group. In most cases, the WT fish group showed “social cohesion” moving together along the narrow space of “mini shoal” in the round bowl. g A snapshot of group behavior during the shoaling assay. Three fish were used as a group in this assay. Arrows indicate individual adult fish. h Mean distance between individuals (cm) was used to show the degree of social cohesion. The dyrk1aa KO fish group showed “loosened” social cohesion, compared to WT fish. Number of trials for this experiment: n = 10. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *** p < 0.001 by Student’s t test

dyrk1aa KO zebrafish show decreased social cohesion

We next tested group behavior of dyrk1aa KO fish using the shoaling bowl assay. Comparison of dyrk1aa KO and WT fish revealed that KO fish group had significantly larger mean distance (10.6 cm, compared to 5.6 cm of WT fish) between each individual fish (Fig. 6g, h; Additional file 11: Movie S3). As a supplemental experiment, we examined group behavior of five fish in a rectangular tank, plotting the path of individual fish after video tracking (Fig. 7a–d; Additional file 12: Movie S4). Social cohesion, aggregation, or shoaling behavior was apparent in the WT fish group; however, the KO fish group showed that individual fish moved independently from one another to suggest deficits in their social interaction.

Tracking of individual fish in a group of five fish show impaired social cohesion in KO fish. a–d Movement of a group of five fish was analyzed after video tracking. The position of individual fish during short periods of 1.5 s at two different time windows (5 and 10 min, respectively) was traced, and their path was presented in different colors (#1 fish in red, #2 fish in green, and so on). Aggregation of WT fish group in a corner of tank is apparent (a, c), compared to independent free swimming of individual KO fish (b, d)

Additional file 11: Movie S3. WT vs KO fish in the shoaling assay. The distance between individual fish in dyrk1aa KO fish group is greater than that of WT fish group. (AVI 1035 kb)

Additional file 12: Movie S4. WT vs KO fish in group behavior. The dyrk1aa KO zebrafish show loose group behavior. (AVI 1141 kb)

Discussion

Although some functional roles of DYRK1A have been implied in mouse studies [19, 20], so far there have been no reported behavioral studies of adult knockout animals with respect to autism. In this study, we generated a KO zebrafish line for dyrk1aa after the discovery of an intragenic microdeletion of DYRK1A in an individual with microcephaly and autism. We demonstrated through social behavioral tests that dyrk1aa KO zebrafish exhibit social impairments reproductive of human ASD phenotypes.

The DYRK1A gene is well conserved in vertebrates, including fish, rodents, and humans. Haploinsufficiency of DYRK1A in humans results in microcephaly and ASD [12], while knockout of Dyrk1a in mice leads to premature death during early development [18]. In the dyrk1aa KO zebrafish, we found similar microcephaly and ASD-like phenotypes, yet the fish were viable without embryonic lethality. This discrepancy may be explained in part by reason of the two orthologous DYRK1A genes in zebrafish, dyrk1aa (NM_001080689) and dyrk1ab (NM_001347831), caused by whole genome duplication of zebrafish [59]. Thus, we can speculate that dyrk1ab may compensate the early lethal phenotype and allow the survival of dyrk1aa KO zebrafish into adulthood. We can confirm this possibility by generating a double KO line of both genes in further studies.

Previous murine model studies have been unable to link altered brain structure of Dyrk1a dysfunction with social behavior as a direct physiological model of ASD. The structural defect in our dyrk1aa zebrafish mutant is reminiscent not only of the Dyrk1a mouse, but also of other zebrafish models of autism candidate genes. They display significant structural abnormalities including microcephaly and cell death in anterior structures. Historically, linking these altered physiological states to behavioral deficits has been hampered by two major limitations. First is the paucity of bona fide genetic models for autism in zebrafish. Secondly, reported tracking programs to investigate adult fish behavior in 3D is subject to extensive variability, in large part due to the speed at which multiple fish are moving in three dimensions.

To overcome these limitations, we introduced two social behavioral tests: the social interaction and shoaling assay. In the social interaction assay, we optimized the (a) number of fish, (b) time window of monitoring, and (c) composition of separator material. Zebrafish are active animals and have a wide range of locomotion moving from side to side or from top to bottom in their tank. We found that a group of three fish, rather than 1–2 fish, was ideal for the social cue to facilitate recognition, provide better cueing effect, and elicit stronger interaction of tester fish. Previous work has shown that the ability to view and recognize others is an important factor of social cueing [60,61,62]. We confirmed these observations by demonstrating that a transparent acrylic plate separator provided better recognition of social cues to tester fish than a metal mesh. Utilizing this assay, we showed that dyrk1aa KO zebrafish have impaired social interaction as seen by frequent movements towards the far zones. Taken together, this newly optimized social interaction assay provides a useful means of investigating social interaction of zebrafish models in neurobehavioral disorders.

Next, we developed a novel shoaling assay, called the “shoaling bowl assay”. Shoaling behavior is considered an adaptive and effective natural anti-predatory response, which has been utilized in behavioral analyses in vertebrates [32, 39]. This behavior mimics the tendency of zebrafish to live together and is a robust tool for measuring social behavior of group animals. We showed that the “mini shoal”, formed at the edge of the round bowl, is a preferred location for zebrafish to move together as a group along the narrow space of the shoal. We tested shoaling behavior in different group sizes (3–7 fish). A minimum group of three fish was used for the shoaling assay given that the fish maintained a constant distance between individuals regardless of the size of the group. With a minimum number of animals and a two-dimensional (2D) approach, analysis of social cohesion in a flat round bowl avoids the complexity of group behavior in a three-dimensional (3D) tank which is the current standard [63, 64]. To our knowledge, the altered social cohesion of dyrk1aa KO is the first experimental demonstration that shoaling behavior of animals can be regulated by a single gene. The interrelationship between anxiety and social cohesion in animal group behavior will be an interesting topic in further studies since collective animal behavior (huddling, flocking, or shoaling) is a defensive strategy employed by many species in response to predatory threat. Our findings open up a new avenue for the study of this evolutionarily important behavior at the molecular and neural circuit levels.

To understand the molecular mechanisms involved in behavioral alterations of KO fish, we analyzed the expression of various neural markers. Among them, we found significant changes in the expression of c-fos and crh mRNAs in specific brain regions of dyrk1aa KO fish. Neuronal activity of KO fish, as indicated by c-fos expression, was lower than that of WT fish in the ventral hypothalamic region during social interaction tests, which suggests that the KO fish brain is less activated by social cues. In addition, crh expression level in the PO area of the hypothalamus of KO fish in the acute social isolation test was found to be lower than that of WT, demonstrating low responsiveness to stress in the context of social isolation. In mammals, the hypothalamic region is a known source of stress hormone secretion, such as CRH, and has been shown to be largely involved in social interaction behaviors [65]. Thus, we can conclude that the reduction in the size of the dyrk1aa KO fish brain exerts structural changes in the neural circuitry involved in executing of proper behavioral responses to external stress signals which is a vital decision-making aspect of social interactions. In future studies, we plan to examine in further detail the neural circuitry directly involved in dyrk1aa function and autism.

In this paper, we have optimized a widely used social interaction test and newly developed the shoaling bowl assay as a convenient method to study group behavior. Furthermore, we showed that these tests can be effectively applied to the study of disease model animals in zebrafish. Together, these data demonstrate that dyrk1aa KO zebrafish not only recapitulate the neuroanatomical defects of humans with DYRK1A mutations but also exhibit similar hallmarks of impairments in social behavior.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified a patient with an intragenic deletion in DYRK1A exhibiting microcephaly and autism. To validate DYRK1A as an autism candidate gene, we generated and characterized a dyrk1aa KO zebrafish model using behavioral tests and molecular techniques. dyrk1aa KO zebrafish displayed microcephaly with social impairments reproductive of human phenotypes of autism. These results indicate a functional deficiency of DYRK1A as an underlying disease mechanism for autism. Our tractable and cost-effective approach provides a useful alternative to the utilization of rodent behavioral models in validating ASD candidate genes; especially, this approach can be used to increase the throughput of much-needed functional modeling for the other candidate autism loci that are being identified by large-scale human genetic studies.

Abbreviations

- 2D:

-

Two-dimension

- 3D:

-

Three-dimension

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorders

- CCe:

-

Corpus cerebelli

- CGH:

-

Comparative genomic hybridization

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DIL:

-

Diffuse nucleus of the inferior lobe

- DLR:

-

Derivative log ratio

- dpf:

-

Days post-fertilization

- DSCR:

-

Down syndrome critical region

- Fb:

-

Forebrain

- Hb:

-

Hindbrain

- hpf:

-

Hours post-fertilization

- Hy:

-

Hypothalamus

- ISCA:

-

International standard cytogenomic array

- KO:

-

Knockout

- LD:

-

Light-dark

- Mb:

-

Midbrain

- mpf:

-

Months post-fertilization

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- PO:

-

Preoptic area

- PVN:

-

Paraventricular nucleus

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- TALEN:

-

Transcription activator-like effector nuclease

- Tel:

-

Telencephalon

- TeO:

-

Tectum opticum

- TeV:

-

Tectal ventricle

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383:896–910.

O’ Roak BJ, Vives L, Fu W, Egertson JD, Stanaway IB, Phelps IG, Carvill G, Kumar A, Lee C, Ankenman K, Munson J, Hiatt JB, Turner EH, Levy R, ODay DR, Krumm N, Coe BP, Martin BK, Borenstein E, Nickerson DA, Mefford HC, Doherty D, Akey JM, Bernier R, Eichler EE, Shendure J. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science. 2012;338:1619–22.

Krumm N, ORoak BJ, Shendure J, Eichler EE. A de novo convergence of autism genetics and molecular neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:95–105.

CYuen RK, Merico D, Bookman M, L Howe J, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Patel RV, Whitney J, Deflaux N, Bingham J, Wang Z, Pellecchia G, Buchanan JA, Walker S, Marshall CR, Uddin M, Zarrei M, Deneault E, D Abate L, AJS C, Koyanagi S, Paton T, Pereira SL, Hoang N, Engchuan W, Higginbotham EJ, Ho K, Lamoureux S, Li W, JR MD, Nalpathamkalam T, et al. Whole genome sequencing resource identifies 18 new candidate genes for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:602–11.

Jiang X, Liu C, Yu T, Zhang L, Meng K, Xing Z, Belichenko PV, Kleschevnikov AM, Pao A, Peresie J, Wie S, Mobley WC, Yu YE. Genetic dissection of the Down syndrome critical region. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:6540–51.

Kang JE, Choi SA, Park JB, Chung KC. Regulation of the proapoptotic activity of huntingtin interacting protein 1 by Dyrk1 and caspase-3 in hippocampal neuroprogenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:62–72.

Ryoo SR, Jeong HK, Radnaabazar C, Yoo JJ, Cho HJ, Lee HW, Kim IS, Cheon YH, Ahn YS, Chung SH, Song WJ. DYRK1A-mediated hyperphosphorylation of Tau. A functional link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34850–7.

Song WJ, Sternberg LR, Kasten-Sportès C, Keuren ML, Chung SH, Slack AC, Miller DE, Glover TW, Chiang PW, Lou L, Kurnit DM. Isolation of human and murine homologues of the Drosophila minibrain gene: human homologue maps to 21q22.2 in the Down syndrome “critical region”. Genomics. 1996;38:331–9.

Møller RS, Kübart S, Hoeltzenbein M, Heye B, Vogel I, Hansen CP, Menzel C, Ullmann R, Tommerup N, Ropers HH, Tümer Z, Kalscheuer VM. Truncation of the Down syndrome candidate gene DYRK1A in two unrelated patients with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1165–70.

Van Bon BW, Hoischen A, Hehir-Kwa J, de Brouwer AP, Ruivenkamp C, Gijsbers AC, Marcelis CL, de Leeuw N, Veltman JA, Brunner HG, de Vries BB. Intragenic deletion in DYRK1A leads to mental retardation and primary microcephaly. Clin Genet. 2011;79:296–9.

Ruaud L, Mignot C, Guët A, Ohl C, Nava C, Héron D, Keren B, Depienne C, Benoit V, Maystadt I, Lederer D, Amsallem D, Piard J. DYRK1A mutations in two unrelated patients. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58:168–74.

Bronicki LM, Redin C, Drunat S, Piton A, Lyons M, Passemard S, Baumann C, Faivre L, Thevenon J, Rivière JB, Isidor B, Gan G, Francannet C, Willems M, Gunel M, Jones JR, Gleeson JG, Mandel JL, Stevenson RE, Friez MJ, Aylsworth AS. Ten new cases further delineate the syndromic intellectual disability phenotype caused by mutations in DYRK1A. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1482–7.

Van Bon BW, Coe BP, Bernier R, Green C, Gerdts J, Witherspoon K, Kleefstra T, Willemsen MH, Kumar R, Bosco P, Fichera M, Li D, Amaral D, Cristofoli F, Peeters H, Haan E, Romano C, Mefford HC, Scheffer I, Gecz J, de Vries BB, Eichler EE. Disruptive de novo mutations of DYRK1A lead to a syndromic form of autism and ID. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:126–32.

Thomazeau A, Lassalle O, Iafrati J, Souchet B, Guedj F, Janel N, Chavis P, Delabar J, Manzoni OJ. Prefrontal deficits in a murine model overexpressing the down syndrome candidate gene dyrk1a. J Neurosci. 2014;34:1138–47.

Altafaj X, Dierssen M, Baamonde C, Martí E, Visa J, Guimerà J, Oset M, González JR, Flórez J, Fillat C, Estivill X. Neurodevelopmental delay, motor abnormalities and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice overexpressing Dyrk1A (minibrain), a murine model of Down’s syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1915–23.

Dierssen M, de Lagrán MM. DYRK1A (dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylated and -regulated kinase 1A): a gene with dosage effect during development and neurogenesis. Sci World J. 2006;6:1911–22.

Guedj F, Pereira PL, Najas S, Barallobre MJ, Chabert C, Souchet B, Sebrie C, Verney C, Herault Y, Arbones M, Delabar JM. DYRK1A: a master regulatory protein controlling brain growth. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:190–203.

Fotaki V, Dierssen M, Alcántara S, Martínez S, Martí E, Casas C, Visa J, Soriano E, Estivill X, Arbonés ML. Dyrk1A haploinsufficiency affects viability and causes developmental delay and abnormal brain morphology in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6636–47.

Arqué G, de Lagrán MM, Arbonés ML, Dierssen M. Age-associated motor and visuo-spatial learning phenotype in Dyrk1A heterozygous mutant mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:312–9.

Arqué G, Fotaki V, Fernández D, Martínez de Lagrán M, Arbonés ML, Dierssen M. Impaired spatial learning strategies and novel object recognition in mice haploinsufficient for the dual specificity tyrosine-regulated kinase-1A (Dyrk1A). PLoS One. 2008;3:e2575.

Stewart AM, Nguyen M, Wong K, Poudel MK, Kalueff AV. Developing zebrafish models of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;50:27–36.

Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Gerlai R. Zebrafish as an emerging model for studying complex brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:63–75.

Parker MO, Brock AJ, Walton RT, Brennan CH. The role of zebrafish (Danio rerio) in dissecting the genetics and neural circuits of executive function. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:63.

Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, Collins JE, Humphray S, McLaren K, Matthews L, McLaren S, Sealy I, Caccamo M, Churcher C, Scott C, Barrett JC, Koch R, Rauch GJ, White S, Chow W, Kilian B, Quintais LT, Guerra-Assunção JA, Zhou Y, Gu Y, Yen J, Vogel JH, Eyre T, Redmond S, Banerjee R, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496:498–503.

Kim CH, Oda T, Itoh M, Jiang D, Artinger KB, Chandrasekharappa SC, Driever W, Chitnis AB. Repressor activity of Headless/Tcf3 is essential for vertebrate head formation. Nature. 2000;407:913–6.

Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, Oda T, Jiang YJ, Maust D, Yeo SY, Lorick K, Wright GJ, Ariza-McNaughton L, Weissman AM, Lewis J, Chandrasekharappa SC, Chitnis AB. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4:67–82.

Kim HG, Ahn JW, Kurth I, Ullmann R, Kim HT, Kulharya A, Ha KS, Itokawa Y, Meliciani I, Wenzel W, Lee D, Rosenberger G, Ozata M, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Nagase T, Tekin M, Kim SH, Kim CH, Ropers HH, Gusella JF, Kalscheuer V, Choi CY, Layman LC. WDR11, a WD protein that interacts with transcription factor EMX1, is mutated in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:465–79.

Kim HG, Kim HT, Leach NT, Lan F, Ullmann R, Silahtaroglu A, Kurth I, Nowka A, Seong IS, Shen Y, Talkowski ME, Ruderfer D, Lee JH, Glotzbach C, Ha K, Kjaergaard S, Levin AV, Romeike BF, Kleefstra T, Bartsch O, Elsea SH, Jabs EW, ME MD, Harris DJ, Quade BJ, Ropers HH, Shaffer LG, Kutsche K, Layman LC, Tommerup N, et al. Translocations disrupting PHF21A in the Potocki-Shaffer-syndrome region are associated with intellectual disability and craniofacial anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:56–72.

May M, Hwang KS, Miles J, Williams C, Niranjan T, Kahler SG, Chiurazzi P, Steindl K, Van Der Spek PJ, Swagemakers S, Mueller J, Stefl S, Alexov E, Ryu JI, Choi JH, Kim HT, Tarpey P, Neri G, Holloway L, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Dorsky RI, Wang T, Schwartz CE, Kim CH. ZC4H2, an XLID gene, is required for the generation of a specific subset of CNS interneurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:4848–61.

Labonne JD, Lee KH, Iwase S, Kong IK, Diamond MP, Layman LC, Kim CH, Kim HG. An atypical 12q24.31 microdeletion implicates six genes including a histone demethylase KDM2B and a histone methyltransferase SETD1B in syndromic intellectual disability. Hum Genet. 2016;135:757–71.

Golzio C, Willer J, Talkowski ME, Oh EC, Taniguchi Y, Jacquemont S, Reymond A, Sun M, Sawa A, Gusella JF, Kamiya A, Beckmann JS, Katsanis N. KCTD13 is a major driver of mirrored neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 copy number variant. Nature. 2012;485:363–7.

Green J, Collins C, Kyzar EJ, Pham M, Roth A, Gaikwad S, Cachat J, Stewart AM, Landsman S, Grieco F, Tegelenbosch R, Noldus LP, Kalueff AV. Automated high-throughput neurophenotyping of zebrafish social behavior. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;210:266–71.

Saverino C, Gerlai R. The social zebrafish: behavioral responses to conspecific, heterospecific, and computer animated fish. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:77–87.

Bedell VM, Wang Y, Campbell JM, Poshusta TL, Starker CG, Krug RG, Tan W, Penheiter SG, Ma AC, Leung AY, Fahrenkrug SC, Carlson DF, Voytas DF, Clark KJ, Essner JJ, Ekker SC. In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system. Nature. 2012;491:114–8.

Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69.

Burgess HA, Granato M. Modulation of locomotor activity in larval zebrafish during light adaptation. J Exp Biol. 2007;210(Pt 14):2526–39.

Rihel J, Prober DA, Schier AF. Monitoring sleep and arousal in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 2010;100:281–94.

Cachat J, Stewart A, Grossman L, Gaikwad S, Kadri F, Chung KM, Wu N, Wong K, Roy S, Suciu C, Goodspeed J, Elegante M, Bartels B, Elkhayat S, Tien D, Tan J, Denmark A, Gilder T, Kyzar E, Dileo J, Frank K, Chang K, Utterback E, Hart P, Kalueff AV. Measuring behavioral and endocrine responses to novelty stress in adult zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1786–99.

Miller N, Gerlai R. Quantification of shoaling behaviour in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Behav Brain Res. 2007;184:157–66.

Wright D, Krause J. Repeated measures of shoaling tendency in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and other small teleost fishes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1828–31.

Buske C, Gerlai R. Shoaling develops with age in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1409–15.

Soppa U, Schumacher J, Florencio Ortiz V, Pasqualon T, Tejedor FJ, Becker W. The Down syndrome-related protein kinase DYRK1A phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and Cyclin D1 and induces cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:2084–100.

Park JS, Ryu JH, Choi TI, Bae YK, Lee S, Kang HJ, Kim CH. Innate color preference of zebrafish and its use in behavioral analyses. Mol Cells. 2016;39:750–5.

Cahill GM, Hurd MW, Batchelor MM. Circadian rhythmicity in the locomotor activity of larval zebrafish. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3445–9.

Ben-Moshe Livne Z, Alon S, Vallone D, Bayleyen Y, Tovin A, Shainer I, Nisembaum LG, Aviram I, Smadja-Storz S, Fuentes M, Falcón J, Eisenberg E, Klein DC, Burgess HA, Foulkes NS, Gothilf Y. Genetically blocking the zebrafish pineal clock affects circadian behavior. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006445.

Tejedor F, Zhu XR, Kaltenbach E, Ackermann A, Baumann A, Canal I, Heisenberg M, Fischbach KF, Pongs O. Minibrain: a new protein kinase family involved in postembryonic neurogenesis in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;14:287–301.

Barallobre MJ, Perier C, Bové J, Laguna A, Delabar JM, Vila M, Arbonés ML. DYRK1A promotes dopaminergic neuron survival in the developing brain and in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1289.

Wong K, Elegante M, Bartels B, Elkhayat S, Tien D, Roy S, Goodspeed J, Suciu C, Tan J, Grimes C, Chung A, Rosenberg M, Gaikwad S, Denmark A, Jackson A, Kadri F, Chung KM, Stewart A, Gilder T, Beeson E, Zapolsky I, Wu N, Cachat J, Kalueff AV. Analyzing habituation responses to novelty in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Behav Brain Res. 2010;208:450–7.

Sackerman J, Donegan JJ, Cunningham CS, Nguyen NN, Lawless K, Long A, Benno RH, Gould GG. Zebrafish behavior in novel environments: effects of acute exposure to anxiolytic compounds and choice of Danio rerio line. Int J Comp Psychol. 2010;23:43–61.

Egan RJ, Bergner CL, Hart PC, Cachat JM, Canavello PR, Elegante MF, Elkhayat SI, Bartels BK, Tien AK, Tien DH, Mohnot S, Beeson E, Glasgow E, Amri H, Zukowska Z, Kalueff AV. Understanding behavioral and physiological phenotypes of stress and anxiety in zebrafish. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205:38–44.

Lau BY, Mathur P, Gould GG, Guo S. Identification of a brain center whose activity discriminates a choice behavior in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2581–6.

DeVries AC. Interaction among social environment, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and behavior. Horm Behav. 2002;41:405–13.

Herget U, Wolf A, Wullimann MF, Ryu S. Molecular neuroanatomy and chemoarchitecture of the neurosecretory preoptic-hypothalamic area in zebrafish larvae. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:1542–64.

Murakami G, Hunter RG, Fontaine C, Ribeiro A, Pfaff D. Relationships among estrogen receptor, oxytocin and vasopressin gene expression and social interaction in male mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:469–77.

Elliott E, Ezra-Nevo G, Regev L, Neufeld-Cohen A, Chen A. Resilience to social stress coincides with functional DNA methylation of the Crf gene in adult mice. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1351–3.

Ziv L, Muto A, Schoonheim PJ, Meijsing SH, Strasser D, Ingraham HA, Schaaf MJ, Yamamoto KR, Baier H. An affective disorder in zebrafish with mutation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:681–91.

Reyhanian N, Volkova K, Hallgren S, Bollner T, Olsson PE, Olsén H, Hällström IP. 17α-Ethinyl estradiol affects anxiety and shoaling behavior in adult male zebra fish (Danio rerio). Aquat Toxicol. 2011;105:41–8.

Miller N, Greene K, Dydinski A, Gerlai R. Effects of nicotine and alcohol on zebrafish (Danio rerio) shoaling. Behav Brain Res. 2013;240:192–6.

Meyer A, Schartl M. Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:699–704.

Dreosti E, Lopes G, Kampff AR, Wilson SW. Development of social behavior in young zebrafish. Front Neural Circuits. 2015;9:39.

Gerlai R. Social behavior of zebrafish: from synthetic images to biological mechanisms of shoaling. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;234:59–65.

Qin M, Wong A, Seguin D, Gerlai R. Induction of social behavior in zebrafish: live versus computer animated fish as stimuli. Zebrafish. 2014;11:185–97.

Cachat J, Stewart A, Utterback E, Hart P, Gaikwad S, Wong K, Kyzar E, Wu N, Kalueff AV. Three-dimensional neurophenotyping of adult zebrafish behavior. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17597.

Maaswinkel H, Le X, He L, Zhu L, Weng W. Dissociating the effects of habituation, black walls, buspirone and ethanol on anxiety-like behavioral responses in shoaling zebrafish—a 3D approach to social behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;108:16–27.

Senst L, Baimoukhametova D, Sterley TL, Bains JS. Sexually dimorphic neuronal responses to social isolation. Elife. 2016;5

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient, who kindly consented to participate in our study.

Funding

C.-H.K. was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grants (2014R1A2A1A11053562 and 2015M3A9A8029261) and the research fund of Chungnam National University; J.-S.L. was supported by the KRIBB Research Initiative Program and the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) grant (CRC-15-04-KIST); D.-S.P. was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant (2016M3A9A5919255); E.E.D. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 MH106826.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H-GK, J-SL, and C-HK designed the experiments; O-HK and H-JC performed the main experiments with the help of EH, KA, K-SH, and Y-MJ; J-HC and S-YY created the dyrk1aa KO zebrafish; O-HK, H-GK, and C-HK wrote the manuscript with the help of TIH, KY, EED, and CES; D-SP and H-WO performed the microarray analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study on “11 and a half years female of northern European ancestry” was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Augusta University, and written informed consent was obtained from the parent of the child for the publication of this report and accompanying images. All experiments using zebrafish were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Chungnam National University (CNU-00620).

Consent for publication

Consents to publish findings and data were provided in the consent form, which was signed by 11 and a half-year-old female and her parent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Characterization of early neural development and larval behavioral tests in WT and dyrk1aa KO fish. (A-F) Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis with various molecular markers at 24 hpf (A, B, lateral view) and 48 hpf (C-F, rostral dorsal view): sox2, neural stem cell marker; neurog1, neuronal determination marker; and cyclin D1, cell proliferation marker. Anterior is to the left. Number of fish used for the analysis: 1) after sox2 staining and photography, each embryo was genotyped for WT (5/19) and KO homozygote (3/19); 2) for neurog1, it was WT (6/16) and KO homozygote (4/16); and 3) for cyclin D1, WT (3/16) and KO homozygote (5/16), respectively. (G) Locomotion response to dark flashes in WT and dyrk1aa KO larvae at 6 dpf. Movement distance was measured by video tracking analysis (cm per every 10 s). With light-on in 30 s-intervals, zebrafish larvae showed a freezing response (yellow box in the graph). However, they showed a startle response to light-off dark condition (gray box). The number of fish used for this assay: n = 14 for WT (+/+), n = 25 for heterozygote (+/−), and n = 9 for KO homozygote (−/−). (H) Circadian rhythms in WT and dyrk1aa KO larvae between 5 and 7 dpf. Circadian rhythms of locomotor activity under LD (day-night) cycles were measured. Both WT and dyrk1aa KO larvae display a similar pattern of locomotor activity in daytime or nighttime. The number of fish used for this assay: n = 11 for control heterozygote (+/−), and n = 13 for KO homozygote (−/−). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (PDF 1219 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Comparison of brain size in WT and dyrk1aa KO fish. (A) Relative size of brain compartments in KO fish brain was shown as a ratio, compared to those in WT fish brain. Also, body length (cm) of WT and KO fish used for this analysis was constant. Tel, Telencephalon; TeO, Tectum Opticum; CCe, Corpus Cerebelli. Number of dissected brains: n = 13 for WT fish and n = 13 for KO fish. (B) Percent of TeV space in the total brain. Mean value for the TeV sizes was measured in relative sections of multiple brain samples. Number of fish used for this assay: n = 6 for WT fish and n = 5 for KO fish. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 by Student’s t test. (PDF 1033 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Analysis of various parameters in the novel tank test. (A, B) Number of entries to the middle or top zone of the tank. (C) Freezing duration. Duration of freezing time (seconds) was measured in every minute. KO zebrafish show reduced freezing behavior, compared to that of WT zebrafish. (D, E) Total distance moved (cm) and mean velocity (cm/s). No significant difference was detected between WT and KO fish. Number of fish used in this assay: n = 8 for WT fish, n = 8 for KO fish, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 by Student’s t test. (PDF 1031 kb)

Additional file 4: Figure S4.

Schematic illustration of the social interaction assay with different separation materials. (A-F) Two kinds of materials were used for the separator: metal mesh (A, B, and E) and a clear acrylic plate (C, D, and F). (B, D) Changes of duration time for tester fish, when added to a different number of fish (1–5 fish) as the social cue group, was analyzed in 4 different zones between 6 and 10 min. Multiple trials (n = 5) were performed for each group size. (E, F) Detailed information for duration time for tester fish in different zones over the course of 15 min. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (PDF 1033 kb)

Additional file 5: Figure S5.

Analysis of various parameters in social interaction assay. (A, B) Video tracking of WT and dyrk1aa KO zebrafish in the social interaction assay. Dashed lines indicate position of a separator and a transparent acrylic plate was used in this experiment. Red lines show tracking of swim movement of WT and KO zebrafish. Fish were tracked every minute for 15 min during the social interaction assay. In this experiment, 3 fish were used as the social cue group in left side and 1 tester fish in right side. (C-F) Duration time for WT and dyrk1aa KO zebrafish in each zone; very close zone “I” (C), close zone “II” (D), far zone “III” (E), and very far zone “IV” (F). (G, H) Total distance moved (cm) and mean velocity (cm/s) are no different in both WT and KO fish during the test. Data were collected from video tracking for 15 min and every minute was analyzed. Number of tester fish used in the assay: n = 30 for WT and n = 30 for KO. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 by Student’s t test. (PDF 1029 kb)

Additional file 8: Figure S6.

Number of transit movements of tester fish at each zone boundary. (A-C) 3 cases of each transit movements were analyzed: movement “I” to “II” (A), “II” to “III” (B), and “III” to “IV” zone (C). Number of tester fish used in this assay: n = 30 for WT and n = 30 for KO. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 by Student’s t test. (PDF 1954 kb)

Additional file 9: Figure S7.

Presence of neuromodulator producing cells in the brain of WT and dyrk1aa KO zebrafish. (A-H) Expression of oxt, th, vglut2.2, and gad1b in the brain of WT and dyrk1aa KO zebrafish at adult stages. In situ hybridization revealed dyrk1aa KO fish show unchanged neuromodulator-producing cells in the brain. (A, B) oxt, oxytocinergic marker. (C, D) vglut2.2, glutamatergic marker. (E, F) th1, dopaminergic marker. (G, H) gad1b, GABAergic marker. Anterior to the top and ventral view. Scale bars: 0.2 mm. (PDF 1051 kb)

Additional file 10: Figure S8.

Social cohesion in different group sizes and water depths in the shoaling assay. (A) Schematic illustrations of the method to measure the distances between individual fish in the shoaling assay. Different numbers of fish were used as a group, ranging from 3 to 7. Social cohesion was represented as a mean distance of individual fish in the group. (B, C) Mean distance between individuals (cm) in a fish group represents the degree of social cohesion. The mean distance for social cohesion was analyzed in 2 different conditions; 1) different group sizes (B) and 2) water depths and volume (C). Number of trials for each experiment: n = 7. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (PDF 1086 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, OH., Cho, HJ., Han, E. et al. Zebrafish knockout of Down syndrome gene, DYRK1A, shows social impairments relevant to autism. Molecular Autism 8, 50 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0168-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0168-2