Abstract

Background

Phoronids, rhynchonelliform and linguliform brachiopods show striking similarities in their embryonic fate maps, in particular in their axis specification and regionalization. However, although brachiopod development has been studied in detail and demonstrated embryonic patterning as a causal factor of the gastrulation mode (protostomy vs deuterostomy), molecular descriptions are still missing in phoronids. To understand whether phoronids display underlying embryonic molecular mechanisms similar to those of brachiopods, here we report the expression patterns of anterior (otx, gsc, six3/6, nk2.1), posterior (cdx, bra) and endomesodermal (foxA, gata4/5/6, twist) markers during the development of the protostomic phoronid Phoronopsis harmeri.

Results

The transcription factors foxA, gata4/5/6 and cdx show conserved expression in patterning the development and regionalization of the phoronid embryonic gut, with foxA expressed in the presumptive foregut, gata4/5/6 demarcating the midgut and cdx confined to the hindgut. Furthermore, six3/6, usually a well-conserved anterior marker, shows a remarkably dynamic expression, demarcating not only the apical organ and the oral ectoderm, but also clusters of cells of the developing midgut and the anterior mesoderm, similar to what has been reported for brachiopods, bryozoans and some deuterostome Bilateria. Surprisingly, brachyury, a transcription factor often associated with gastrulation movements and mouth and hindgut development, seems not to be involved with these patterning events in phoronids.

Conclusions

Our description and comparison of gene expression patterns with other studied Bilateria reveals that the timing of axis determination and cell fate distribution of the phoronid shows highest similarity to that of rhynchonelliform brachiopods, which is likely related to their shared protostomic mode of development. Despite these similarities, the phoronid Ph. harmeri also shows particularities in its development, which hint to divergences in the arrangement of gene regulatory networks responsible for germ layer formation and axis specification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lophophorates (e.g., Ectoprocta, Phoronida and Brachiopoda) are members of the clade Spiralia and besides the common presence of an anterior tentacular feeding device, the lophophore, they also share non-spiral embryological features, such as a radial cleavage [1]. Fate-mapping experiments on the development of Ectoprocta (e.g., Membranipora membranacea) revealed that ectoprocts exhibit a unique stereotypical development [2], whilst phoronids and brachiopods display a typical radial development with important similarities in their embryonic fate maps [3]. Interestingly, molecular studies in rhynchonelliform and craniiform brachiopods demonstrated that the early embryonic patterning is defining the mode of gastrulation as protostomic or deuterostomic [4]. However, with the exception of Hox genes [5], molecular studies on embryonic development of phoronids are still lacking and are therefore important to understand the precise timing of germ layer segregation and cell specification. Furthermore, due to their informative phylogenetic position (as sister group, together with Ectoprocta, to Brachiopoda), phoronids can shed light on whether a similar developmental mode is shaped by conserved molecular mechanisms in closely related taxa.

Phoronids are small, filter-feeding, sessile marine worms that are placed by molecular phylogenetic analyses together with the Brachiopoda and Ectoprocta in a clade called Lophophorata (Fig. 1a) [6,7,8,9,10]. Phoronida is subdivided into two main taxa, Phoronis Wright 1856 and Phoronopsis Gilchrist 1907, among which one species, Phoronis ovalis, forms the sister species (Fig. 1a) [11]. Most phoronids are characterized by a planktotrophic actinotroch larva (Fig. 1b), which undergoes a rapid, catastrophic metamorphosis to give rise to the adult body plan [12, 13].

Gross morphology and phylogenetic position of Phoronopsis harmeri. a Phylogenetic position of phoronids and Phoronopsis harmeri [11]. b Characteristic actinotroch larva with 12 tentacles. c Anterior region of Phoronopsis harmeri with a terminal anterior lophophore, used for collection of food particles and respiration, and a posterior trunk. d Ampulla of a mature female animal with visible oocytes. Anterior is to the top

The development of phoronids has been described by a number of authors and, except for differences in the cleavage pattern and the mode of coelom formation, appears to be similar between species [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Cleavage is holoblastic, and the first two divisions are meridional along the animal–vegetal main axis [14,15,16,17, 21,22,23,24,25, 27, 28]. At the eight-cell stage, the embryo is composed of an animal and a vegetal tier of four cells, but the blastomeres vary in their arrangement between embryos [14,15,16,17, 21,22,23,24,25, 27, 28]. The variability is also seen in the next division rounds and led some authors to describe the phoronid cleavage pattern as radial or biradial [15, 17, 19,20,21,22, 27, 29], spiral [14, 23, 24, 30, 31], or even a transition between a radial and spiral pattern [32, 33]. By the 64-cell stage, the embryo develops into a ciliated blastula [17, 21, 23,24,25, 27,28,29, 33]. Blastulae can be thick walled with a small blastocoel (e.g., Phoronis psammophila) [29] or thin walled with an extensive blastocoel (e.g., Phoronopsis harmeri) [24, 27].

Gastrulation begins with the flattening of the vegetal pole of the embryo and the subsequent invagination of the archenteron, that forms a centrally located blastopore [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33]. In phoronids, the animal–vegetal axis of the early embryo does not correspond to the anterior–posterior axis of the larva [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33]. During gastrulation, both the animal pole and the blastopore shift towards the future anterior end of the larva, whilst the embryo and the developing archenteron elongate in an anterior to posterior direction, establishing the future plane of the bilateral symmetry of the larva [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33]. An anterior ectodermal thickening leads to the formation of the apical organ [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33]. At the end of gastrulation, the blastopore is reduced to a round-shaped anterior remnant that will form the mouth, while the anus will open independently at the posterior end of the larva [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33].

Mesoderm originates in two waves: from an anterior domain of the invaginating archenteron at early gastrula stage and from a posterior ventrolateral domain of the elongated archenteron at larva stage [14,15,16,17,18,19, 24,25,26, 30]. The anterior mesoderm will form the cavity that fills the pre-oral lobe and the muscles of the pre-oral lobe, and the posterior mesoderm will form the trunk coelom (metacoel) [14,15,16,17,18,19, 24,25,26, 30]. The formation of the pre-oral lobe cavity shows variation between species. Mesodermal cells can proliferate and form the lining of a coelom (protocoel) (e.g., Phoronis vancouverensis (referred to as Phoronis ijimai), Phoronis psammophila and Phoronopsis harmeri) [14, 20, 26, 29, 33,34,35], or can form a cell mass that is surrounded by extracellular matrix (e.g., Phoronis muelleri) [36].

Blastomere ablation experiments on Phoronis vancouverensis (referred to as Phoronis ijimai) and Phoronopsis harmeri have demonstrated the large regulative potential of phoronids, since blastomeres isolated at the two-cell stage are able to produce complete, but diminutive embryos [27]. Moreover, fate-mapping experiments in Phoronis vancouverensis have shown that the early animal tier of the eight-cell embryo forms only ectoderm, while the early vegetal tier forms ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm [17]. A later study on the same species suggested that muscles and neurons originate from portions of endoderm and ectoderm, and that the intestine forms by ingression of the posterior ectoderm [18].

In this study, we investigated the embryonic gene expression of the phoronid Phoronopsis harmeri Pixell, 1912. Ph. harmeri occurs in very large numbers in coastal intertidal mudflats of the North Pacific. The body of the adult animal is subdivided into two main compartments, an anterior lophophore and a posterior trunk (Fig. 1c) with a terminal ampulla (Fig. 1d) [37]. Fertilization takes place internally in the coelomic fluid of the female trunk (Fig. 1d) and each gravid adult can release hundreds of eggs. The cleavage pattern of Ph. harmeri is a debated subject; some authors consider it radial [25, 27, 33] and others spiral (referred as Ph. viridis in [24]).

To identify the appearance and segregation of the primary embryonic fates in Ph. harmeri, we identified orthologs of evolutionary conserved developmental genes often associated with anterior (otx, gsc, six3/6, nk2.1) [38,39,40,41,42], posterior (cdx, bra) [43, 44] and endomesodermal identities (foxA, gata4/5/6, twist) [45,46,47,48,49,50], and revealed their spatial expression during embryonic development by whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH). By comparing our findings with brachiopods, the proposed sister group (together with Ectoprocta) to phoronids, we show that Ph. harmeri shares more molecular similarities to rhynchonelliform (e.g., Terebratalia transversa) than craniiform (e.g., Novocrania anomala) brachiopods. We propose that these similarities are associated with their common gastrulation mode (protostomy) and likely reflect the ancestral molecular embryonic patterning of the last common ancestor of brachiopods and phoronids.

Results

Embryological description of the development of Ph. harmeri

To better understand the spatial and temporal expression of the candidate developmental genes, we first analyzed the developmental stages of Ph. harmeri using differential interference contrast (DIC) and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

After fertilization, two polar bodies are formed; the first polar body is formed soon after the release of the eggs into the seawater, and the next about 30 min later, both of which remain associated with the embryo due to the presence of a thick vitelline membrane. The first division is meridional and occurs approximately 2 h after the egg contacts the seawater (Fig. 2a). The second cleavage is also meridional but perpendicular to the preceding division and takes place 1 h after the completion of the previous division (Fig. 2b). The third division starts around 30–60 min later in the equatorial plane, with the blastomeres of the animal quartets oriented directly above the vegetal ones (Fig. 2c). This third cleavage and the next two divisions result in the formation of different blastomere arrangements of spiral-like appearance (Fig. 2c–e). A ciliated blastula with cone-shaped cells is formed at approx. 6–8 h post-fertilization (hpf) (Fig. 2f). Within the next couple of hours, the blastula hatches and starts to swim. Around 10 hpf, a large blastocoel is evident (Figs. 2g, 3a).

The embryonic development of Ph. harmeri. Nomarski images of living embryos of Ph. harmeri at representative stages of development: cleavage (a–e), blastula (f–g), gastrula (h–i) and larva (j–k). The egg undergoes its first radial holoblastic cleavage at 2 hpf (a) and forms a hatching blastula around 6–10 hpf (f). Gastrulation starts at 20 hpf (h) at the vegetal pole of the embryo and results in the flattening of the vegetal surface. At late gastrula stage (30 hpf) (i), the apical organ shifts anteriorly, the archenteron elongates posteriorly and the anterior–posterior axis becomes oblique. At early larva stage (40 hpf) (j), the embryo begins to elongate along the anterior–posterior axis and the blastopore becomes the mouth of the future larva. A thick tissue is formed at the dorsal ectoderm and around the mouth that will form the future pre-oral lobe. The bilateral symmetry is evident. The pre-tentacle actinotroch larva is formed around 60 hpf (k), with a prominent pre-oral lobe, a fully compartmentalized, functional gut and evident tentacle bulbs. h–k depict embryos in lateral view and h′–k′ show embryos in vegetal view. Insets show different focal planes of the embryos. In all panels, anterior is to the left

Immunohistochemistry on blastula (a), gastrula (b–c) and larva stages (d–f) of Ph. harmeri. Immunohistochemistry on blastula, gastrula and larva stages labeled against acetylated tubulin (gray) and DAPI (blue). b–f Depict embryos in lateral view (lv) and b′–f′ show embryos in vegetal view (vv). In panels depicting gastrulae and larvae stages, anterior is to the left. am, anterior mesoderm; an, anus; ar, archenteron; at, apical organ; bc, blastocoel; bp, blastopore; es, esophagus; in, intestine; mo, mouth; ne, nephridium; np, nephridial primordium; pl, pre-oral lobe; pm, posterior mesoderm; st, stomach; tb, tentacle bulb; te, tentacle; tr, tentacular ridge; tt, telotroch; vp, vegetal plate. Scale bar: 25 µm

The onset of gastrulation occurs at approximately 20 hpf (early gastrula stage) with a flattening of the vegetal pole and the formation of a shallow indentation (Figs. 2h, 3b). At 30 hpf (late gastrula stage), cells ingress in the blastocoel and the archenteron epithelium thickens and elongates, due to the axial elongation of the embryo. The ciliated apical organ shifts approximately 90° from its original position and establishes the future anterior end of the larva. A number of mesodermal cells (anterior mesoderm) delaminate from the anterior endodermal–ectodermal boundary (Figs. 2i, 3c).

At early larva stage (40 hpf), the former blastopore is located anterior–ventrally, where it eventually forms the future mouth of the larva. The archenteron then narrows and becomes a posteriorly blind tube. The ectoderm grows and forms the pre-oral lobe, which protrudes anteriorly and ventrally of the mouth. Some mesodermal cells spread into the pre-oral lobe and others migrate posteriorly to form two lateral tiers along both sides of the archenteron. The posterior–ventral region of ectoderm thickens and leads to the formation of the tentacular ridge; which will later give rise to the first pair of tentacles (Figs. 2j, 3d).

At 50–60 hpf, the pre-tentacle actinotrocha larva is almost formed. The pre-oral lobe becomes more prominent. The archenteron differentiates into esophagus (foregut), stomach (midgut) and intestine (hindgut) and the anus opens after the junction of intestinal and ectodermal cells. The tentacle bulbs are evident and the protonephridial primordia are established (Figs. 2k, 3e). At 100 hpf (5 days), the larva has already three pairs of tentacles and a well-defined telotroch around the anus (Fig. 3f). The posterior mesoderm forms at the junction of the stomach and the intestine, the protonephridia are evident and the mid part of the stomach protrudes to develop a stomach diverticulum (Fig. 3f).

Molecular patterning of the endomesoderm of Ph. harmeri

To reveal the spatial and temporal appearance of endodermal and mesodermal fates, we analyzed the expression of evolutionarily conserved molecular markers associated with the development of endomesodermal tissues, foxA, gata4/5/6 and twist, in blastula, gastrula and larva stages of Ph. harmeri.

FoxA is already expressed at the blastula stage, in few cells of the vegetal pole (Figs. 4a, 5a). At the early gastrula stage, the gene is expressed asymmetrically in the anterior ventrolateral ectoderm and in the whole vegetal plate (Figs. 4b, 5d). Later, at the late gastrula stage, the expression of foxA is retained mostly around the blastopore and faintly in the invaginating archenteron (Fig. 4c). In the early larva, foxA expression is seen around the mouth, and the ventral ectoderm (Fig. 4d), where it remains at the pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Figs. 4e, f, 5j).

Expression of endomesodermal, anterior and posterior markers during the embryonic development of Ph. harmeri. WMISH of otx, gsc, six3/6, nk2.1, cdx, bra, foxA, gata4/5/6 and twist in blastula, early gastrulae, late gastrulae, early larvae, pre-tentacle larvae and 6-tentacle larvae of Ph. harmeri. The panels of the first columns (a–bbb) depict embryos in lateral view and the panels of the second columns show embryos in vegetal view (a′–bbb′). Insets in x′, cc′, jj–jj′, nn′, pp and aaa–aaa′ show different focal planes of the embryos. Black arrow indicates the ectodermal expression of otx at the domain that gives rise to the apical organ. The inset in zz′ and pp′ shows different focal planes and higher magnification of the indicated domains. The row below the matrix depicts enlarged images of the insets in x′, cc′, jj–jj′, nn′, pp–pp′, zz′ and aaa–aaa′. In panels depicting gastrulae and larvae stages, anterior is to the left

Co-expression analysis of marker genes by double fluorescent WMISH during the development of Ph. harmeri. Relative spatial expression of otx and foxA (a), otx and gsc (b, f, l), gata4/5/6 and foxA (c), foxA and twist (d), six3/6 and twist (e, h), cdx and nk2.1 (g), bra and nk2.1 (i), bra and foxA (j) and six3/6 and otx (k). Right insets in d, e, k show embryos in vegetal view. Every picture is a full projection of merged confocal stacks. Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Anterior is to the left

Gata4/5/6 is expressed at the blastula stage, in few cells of the vegetal pole, overlapping with foxA (Figs. 4g, 5c). At the early gastrula stage, gata4/5/6 is expressed in the vegetal plate which will later ingress to form the archenteron (Fig. 4h). At the late gastrula stage, transcripts of the gene are only detected in the invaginating archenteron (Fig. 4i), where they remain at the early, pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Fig. 4j–k). At the six-tentacle larva stage, the expression of gata4/5/6 is restricted to the pyloric sphincter (Fig. 4l).

The mesodermal marker twist starts to be expressed at the early gastrula stage, in an anterior ventrolateral cell population of the vegetal plate, located adjacently to the expression of foxA (Figs. 4n, 5d). At the late gastrula stage, twist expression is detected at the anterior mesoderm (Figs. 4o, 5h). At the early larva stage, as some of these anterior mesodermal cells migrate posteriorly, forming two lateral tiers along both sides of the archenteron, twist is expressed in both the pre-oral mesoderm and these two ventrolateral tiers (Fig. 4p). In the pre-tentacle larva, the expression of twist remains in clusters of cells of the pre-oral and post-oral mesoderm, and the two ventrolateral tiers of mesoderm (Fig. 4q). At the six-tentacle larva stage, twist expression is additionally seen at the posterior and tentacular mesoderm (Fig. 4r).

Anterior–posterior molecular patterning of Ph. harmeri

To identify the segregation of the embryonic fates along the anterior–posterior axis, we analyzed the expression of genes with a conserved anterior expression, such as orthodenticle (otx), goosecoid (gsc), six3/6 and nk2.1, and genes commonly involved in the specification of posterior tissues, such as caudal (cdx) and brachyury (bra), in blastula, gastrula and larva stages of Ph. harmeri.

Otx is expressed broadly at the blastula stage, throughout the vegetal hemisphere into the animal hemisphere, excluding the animal pole (Figs. 4s, 5a, b). By the early gastrula stage, the gene is restricted in the anterior lip of the blastopore and the anterior part of the invaginating archenteron (Figs. 4t, 5f). In the late gastrula, the expression of the gene remains in the anterior blastoporal lip and the anterior domain of the archenteron, and also initiates in few cells of the anterior ectoderm, a region that will form the future apical organ (Fig. 4u). At the early larva stage, the gene is expressed in the most anterior region of the ventral ectoderm of the pre-oral lobe, that will later form the neuronal-rich edge of the pre-oral hood, the mouth, and two cell clusters of the apical organ (Fig. 4v), where it remains at the pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Figs. 4w, x, 5l). Additionally, otx expression is detected in a small cell cluster of the most posterior ventral ectoderm (Fig. 5k).

Gsc expression initiates on one side of the blastula, within the otx-positive domain (Figs. 4y, 5b). Later, at the early gastrula stage, gsc is expressed in an ectodermal domain of the vegetal plate that corresponds to the anterior blastoporal lip (Fig. 4z), overlapping with otx at the most anterior part (Fig. 5f). At the late gastrula stage, the gene remains active around the blastopore (Fig. 4aa). In the early larva, the expression of gsc is restricted in the ventral ectoderm of the pre-oral lobe and the mouth, overlapping with otx (Fig. 4bb), where it remains at the pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Figs. 4cc, dd, 5l).

Six3/6 is expressed in approximate 4–5 cells of the animal pole already at the blastula stage (Fig. 4ee). At the early gastrula stage, the expression of the gene remains in the animal pole, in the region that will give rise to the future apical organ, and an anterior ventrolateral cell population of the vegetal plate, which corresponds to the anterior mesoderm as it overlaps with twist expression (Figs. 4ff, 5e). In the late gastrula, transcripts of the gene are found at the apical organ, the anterior mesoderm and a few scattered cells of the archenteron (Figs. 4gg, 5h). At the early larva stage, six3/6 expression is seen in the apical organ, overlapping partially with otx, clusters of cells of the ventral ectoderm and the developing midgut (Fig. 4hh), and some pre-oral mesodermal cells, where it remains at the pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Figs. 4ii, jj, 5k). At the six-tentacle larva stage, transcripts of six3/6 are also detected in individual cells of the edge of the pre-oral hood, possibly muscles (Fig. 4jj).

Nk2.1 is first expressed in an ectodermal domain of the vegetal plate, where the anterior blastoporal lip will form, at the early gastrula stage (Fig. 4ll). In the late gastrula, the expression of the gene remains in the anterior blastoporal lip and also initiates in the most posterior region of the developing archenteron (Figs. 4mm, 5g, i). At the early larva stage, nk2.1 is expressed at the ventral ectoderm of the pre-oral lobe and the intestine (Fig. 4nn), where it remains at the pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages (Fig. 4oo, pp).

Cdx starts expressing at the early gastrula stage, in one group of cells of the vegetal plate that correspond to the posterior blastoporal lip (Fig. 4rr). In the late gastrula, transcripts of cdx are detected in the posterior region of the developing archenteron, where they overlap with the expression of nk2.1, and in the posterior ectoderm that will later form the anus (Figs. 4ss, 5g). At the early, pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages, cdx expression is restricted to the intestine (Fig. 4tt–vv).

The expression of bra initiates only at the late gastrula stage, in the posterior blastoporal lip that will give rise to the developing midgut (Figs. 4yy, 5i). At the early larva stage, the expression of the gene shifts to the ventral domain of the midgut and few cells of the posterior ventral ectoderm (Fig. 4zz). At the pre-tentacle larva stage, transcripts of bra are retained in the ventral midgut and expand in more cells of the ventral ectoderm overlapping with foxa expression, as well as the posterior ciliary band (Fig. 4aaa, 5j). In the six-tentacle larva, transcripts of bra are detected also in the most posterior domain of the intestine, similarly to cdx, as well as the ventral ectoderm and the stomach diverticulum (Fig. 4bbb).

A summary of all gene expression patterns described in this study is provided in Fig. 6.

Summary of gene expression during Ph. harmeri embryonic development. Schematic representation of the expression patterns of endomesodermal, anterior and posterior markers during embryonic development of Ph. harmeri. a The endodermal genes foxA and gata4/5/6 are expressed in the vegetal plate in blastula and later on are patterning the formation of the archenteron. FoxA is eventually confined in the foregut, whilst gata4/5/6 is expressed in the midgut. The mesodermal marker twist is labeling the anterior and posterior mesoderm and its derivatives. b The anterior gene six3/6 is expressed in the animal pole in blastula and at the gastrula stage is also activated in the anterior mesoderm and clusters of cells of the future midgut. At the early, pre-tentacle and six-tentacle larva stages six3/6 is restricted in the apical organ, anterior mesoderm and the oral ectoderm. Otx is expressed broadly at the blastula stage, and in gastrula it labels the anterior lip of the blastopore, adjacent to the expression of nk2.1 and gsc. At the gastrula stage, otx, nk2.1 and gsc are labeling the anterior–ventral ectoderm. Otx is also expressed in the future apical organ and the future midgut, and nk2.1 is additionally labeling the future hindgut. Later on, otx and nk2.1 are marking the ventral ectoderm of the pre-oral lobe. Otx together with gsc are demarcating the mouth. Additionally, otx labels the apical organ and nk2.1 is expressed strongly in the intestine and in the cardiac sphincter. c The posterior markers bra and cdx are expressed in the posterior lip of the blastopore at the gastrula stage. Bra is expressed in the ventral midgut, the ventral ectoderm and the posterior ciliary band, whilst cdx is confined in the intestine. At the six-tentacle larva stage, bra is activated in the intestine, the stomach diverticulum and the ventral ectoderm. The depicted expression patterns are for guidance and not necessarily represent exact expression domains. Drawings are not to scale. LV, lateral view; VV, vegetal view

Discussion

Brachyury seems to be unrelated with gastrulation, hindgut and mouth patterning in phoronids

Comparison of embryos from different evolutionary lineages has shown that the molecular interplay of axial and cellular specification is sometimes characterized by a remarkable conservation of expression patterns for many genes, but also by important lineage-specific novelties [51,52,53,54,55]. To better understand the ancestral molecular underpinnings of cellular identities and their variability, more molecular data are needed from understudied embryos, such as the phoronids. Here, we analyzed the expression patterns of the evolutionarily conserved anterior (otx, gsc, six3/6, nk2.1), posterior (cdx, bra) and endomesodermal (foxA, gata4/5/6, twist) markers in the phoronid Ph. harmeri. Our study shows an expected degree of conservation in embryonic molecular patterning, but also highlights a number of unexpected expression profiles.

Conserved examples of gene expression are, for example, foxA, gata4/5/6 and cdx in patterning the development and regionalization of the phoronid embryonic gut, with foxA expressing in the presumptive foregut, gata4/5/6 demarcating the midgut and cdx confining to the hindgut, similar to what is reported in a vast number of bilaterians, such as ecdysozoans [46, 56, 57], echinoderms [47, 58, 59], spiralians [60,61,62], and vertebrates [63,64,65].

Moreover, clusters of cells of the phoronid midgut (as well as the anterior mesoderm) also express the well-conserved anterior marker six3/6 [2, 39, 41, 42, 66,67,68]. Similar domains of six3/6 expression have been reported in the endomesoderm of brachiopods and bryozoans [2, 4], hemichordates [39], the mesenchyme cells of echinoderms [69] and the endoderm of cnidarians [67].

Interestingly, another conserved anterior/CNS marker, nk2.1 [39, 41, 45, 70, 71], labels the hindgut in phoronids, similar to what is reported in some annelids [45], hemichordates [72], and cephalochordates [73]. Nk2.1 also displays a notable difference in the phoronid compared to other animals examined [39, 41, 45, 70, 71], as this gene is not expressed in the future anterior end of the larva, where the apical organ will form, but rather localizes at the edge of the pre-oral hood, likely in developing neurons.

Surprisingly, brachyury, an evolutionary conserved transcription factor often treated as a hallmark for either gastrulation movements or patterning of the mouth and hindgut in protostomes [50, 57, 74,75,76], seems to be unrelated with these embryonic events in phoronids. Bra starts to be expressed only after gastrulation initiates, and exhibits a dynamic expression pattern, labeling the ventral region of the midgut that will form the stomach diverticulum (a distinct structure of the midgut rich in secretory cells with enormous endoplasmic reticulum [77]), the ventral ectoderm, and the posterior ciliary band. Expression of bra in the ventral ectoderm has also been reported in acoels- that corresponds to the site where the mouth will form [66]-, and in the developing ciliated band (velar rudiment) of the mollusc Crepidula [70]. Functional data would further elucidate whether this ‘module’ of bra expression is conserved within these taxa, or has been independently recruited. Another interesting property of bra expression pattern is its late activation (six-tentacle larva stage) in the most posterior part of the intestine, which might be related to the fact that during metamorphosis the larval intestine is kept and transforms into the intestine of the juvenile [20, 77].

Comparative molecular embryology between Phoronida and Brachiopoda

Previous embryonic comparisons based on fate maps between a number of brachiopod species (T. transversa, Hemithiris sp., Terebratulina sp. and N. anomala) and phoronids (Phoronis vancouverensis) suggested differences in the timing of axis and regional specification [3, 17, 78,79,80]. For instance, in P. vancouverensis and the rhynchonelliform brachiopods T. transversa, Hemithiris sp. and Terebratulina sp, axis formation is related to the movement of cells along the dorsal side of the future anterior–posterior axis of the larva during late gastrulation, whilst in the craniiform brachiopod N. anomala the larval anterior–posterior axis corresponds to the animal–vegetal axis of the egg and that axis is set up already before the blastula stage [3, 17, 78,79,80]. Recent molecular data from T. transversa and N. anomala development also support the notion that an anterior–posterior molecular re-patterning of the blastopore occurs at the gastrula stage in T. transversa, which takes place before axial elongation, unlike in N. anomala, where such a symmetry-breaking event is absent [4].

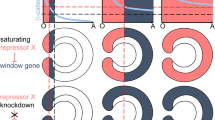

Our molecular comparison of phoronid and brachiopod development confirmed some of the conclusions from the aforementioned studies and revealed some conservation of gene topology between Ph. harmeri, T. transversa and N. anomala. Beside these similarities, we focus here on the differences that seem to correlate with their different developmental modes (Fig. 7).

Comparison of embryonic gene expression patterns in representative developmental stages of Novocrania anomala, Terebratalia transversa and Phoronopsis harmeri. Schematic representation of the expression patterns of endomesodermal, anterior and posterior markers during gastrulation, axial elongation and larva formation of two members of Brachiopoda (N. anomala and T. transversa) and one member of Phoronida (Ph. harmeri). The asterisk is indicating the anterior domain. abl, anterior blastoporal lip; an, anus; bp, blastopore; mo, mouth; pbl, posterior blastoporal lip; vp, vegetal plate

In particular, an interesting difference was observed in the specification of the phoronid mesoderm. In Ph. harmeri, the anterior mesoderm gets specified at the early gastrula stage, as revealed from the expression of the mesodermal marker twist, thus the timing of mesoderm specification is more similar to N. anomala than to T. transversa, where mesoderm is already specified at the blastula stage [4, 48]. In addition to twist, mesoderm development in phoronids is also patterned by six3/6, a conserved anterior marker, in contrast to brachiopods, where six3/6 is solely expressed in the anterior ectoderm and endoderm [4, 41]. However, no expression of six3/6 is observed in the posterior mesoderm of phoronids at the six-tentacle larva stage. This variability in mesodermal patterning might be related to different embryological sources of the anterior and posterior mesoderm [18, 25]. More molecular studies on mesoderm development are needed in phoronids, to clarify whether the formation of posterior mesoderm utilizes different molecular mechanisms from anterior mesoderm.

Other genes that reflect differences in the timing of fate specification are the posterior marker cdx and the anterior markers otx, gsc and nk2.1. In Ph. harmeri, posterior fates seem to be not yet established at the blastula stage, as indicated by the lack of expression of the posterior marker cdx, in contrast to brachiopods, where cdx is localized at the vegetal pole of the blastula and already demarcates the future posterior territory of the embryo [4]. In Ph. harmeri, cdx starts to be expressed at the early gastrula stage only in the posterior blastoporal lip, similar to T. transversa but not to N. anomala, where the gene remains activated around the blastopore until early larva stage [4]. The restriction of cdx in the posterior blastoporal lip in Ph. harmeri is related to different gastrulation modes and blastoporal fates observed between species (Ph. harmeri and T. transversa exhibit protostomy, while N. anomala is deuterostomic). Nevertheless, in all three species, the expression of cdx will eventually be restricted to the posterior region of the larval gut (that corresponds to the intestine in Ph. harmeri) (this study, [4]).

Regarding anterior fate specification, a surprising difference was seen in the early expression of otx, which in brachiopods is detected in the anterior pole [4], whilst in Ph. harmeri otx is expressed broadly, excluding the animal pole. Differences were also observed in the relative position of the future anterior structures and oral ectoderm patterning during gastrulation, since neither nk2.1 nor gsc demarcate the future anterior end of Ph. harmeri larva, as described in brachiopods ([4, 41], this study). The absence of expression of these anterior markers in the future anterior end of Ph. harmeri likely reflects the uncoupling of the animal–vegetal and anterior–posterior axes observed during phoronid development [17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 33]. However, nk2.1 and gsc are exclusively expressed in the anterior lip of the blastopore in Ph. harmeri during gastrulation, similarly to what is reported in T. transversa, but different from N. anomala, where the expression of these genes is seen mainly in the anterior region of the embryo that remains separated from the blastopore throughout development (this study, [4]). The expression of anterior markers in the anterior blastoporal lip in Ph. harmeri suggests a contribution of this region to the oral ectoderm (and mouth) formation. This is, once more, similar to what is reported in the protostomic brachiopod T. transversa [4], and therefore reflects an overall conserved molecular patterning system during gastrulation of both organisms, likely associated to their shared mode of gastrulation and blastoporal fates.

Another intriguing difference is the potential role of nk2.1 in patterning posterior tissues in Ph. harmeri, whilst in brachiopods the orthologous gene is only involved in the specification of the anterior structures [4, 41]. The expression of nk2.1 in posterior patterning and hindgut formation in phoronids, but not in brachiopods, might be attributed to the fact that Ph. harmeri possess a planktotrophic larva with a tripartite, functional gut, whilst T. transversa and N. anomala form lecithotrophic larva with only a gut anlage. The hindgut of the planktotrophic larva of Membranipora membranacea (Ectoprocta) is devoid of nk2.1 [2], and, unfortunately, neither expression nor functional data are available for the planktotrophic larva of linguliform brachiopods, which would elucidate whether nk2.1 has a conserved role in patterning the hindgut of lophophorates, or this expression has been co-opted in phoronids.

In general, with the exception of the timing of mesoderm specification, the rhynchonelliform brachiopod T. transversa and the phoronid Ph. harmeri appear to share more similarities in developmental patterning and the cellular specification than either does with the craniiform brachiopod N. anomala. Similar conclusions emerged from the previous comparative embryonic fate map studies conducted between brachiopods and phoronids [3, 17, 78,79,80], suggesting that the last common ancestor of lophophorates likely shared an early molecular embryonic patterning similar to the extant rhynchonelliform brachiopods and phoronids. To test this hypothesis, functional data are needed to unravel and compare the gene regulatory networks underlying germ layer formation and axis specification in phoronids and different groups of brachiopods.

Conclusions

In this work, we provide a molecular characterization of the embryogenesis of the phoronid Ph. harmeri, with detailed gene expression profiling of marker genes related to cell and axis specification during animal development. We show that the future endodermal and anterior territories appear to be specified by the blastula stage, in contrast to posterior fates that are established later in development. Comparing the embryonic patterning of Ph. harmeri with available data of brachiopods, the proposed sister group to Phoronida (and Ectoprocta), we observe more similarities with rhynchonelliform than with craniiform brachiopods, probably related to their different gastrulation modes. Our findings suggest that the last common ancestor of Lophophorata likely shared an early molecular embryonic patterning similar to the extant rhynchonelliform brachiopods and phoronids, which was secondarily modified in craniiforms brachiopods and ectoprocts.

Methods

Animal systems

Adult specimens of Phoronopsis harmeri Pixell, 1912 were collected at the sand flat of Gaffney point, close to the main channel, at low tide, in Bodega Bay, California, USA (38° 18′ 51.9012″ N 123° 3′ 12.3012″ W), in April. We follow the suggestion of Marsden, who reports that Phoronopsis harmeri is synonymous to Phoronopsis viridis [81]. Eggs were obtained from gravid female animals by puncturing the posterior body wall. Fertilization occurred instantly, due to the presence of sperm in the coelom [34]. The embryos were kept in clean seawater at 9 °C and were fed with concentrated Rhodomonas algae from the pre-tentacle larva stage onwards.

Gene cloning and orthology assignment

Putative orthologous sequences of genes of interest were identified by tBLASTx search against the transcriptome of Phoronopsis harmeri. The transcriptome was made using a mix of early developmental stages and larva stages and is available at https://doi.org/10.18710/89HNMI. Gene orthology was tested by reciprocal BLAST against NCBI Genbank. Amino acid alignments were made with MUSCLE. RAxML (version 8.2.9) was used to conduct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis (Additional file 1). Fragments of the genes of interest were amplified from cDNA of Ph. harmeri by PCR using gene-specific primers. PCR products were purified and cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and the identity of inserts was confirmed by sequencing.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Embryos were manually collected, fixed, and processed for in situ hybridization as described in [82]. Labeled antisense RNA probes were transcribed from linearized DNA using digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Whole mount immunohistochemistry

Animals were collected manually, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in SW for 60 min, washed 3 times in PBT and incubated in 4% sheep serum in PBT for 30 min. The animals were then incubated with commercially available primary antibodies (anti-acetylated and anti-tyrosinated tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody, dilution 1:250 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) overnight at 4 °C, washed 10 times in PBT, and followed by incubation in 4% sheep serum in PBT for 30 min. Specimens were then incubated with a secondary antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by 5 washes in PTW. Nuclei were stained with DAPI.

Documentation

Colorimetric WMISH specimens were imaged with a Zeiss AxioCam HRc mounted on a Zeiss Axioscope A1 equipped with Nomarski optics and processed through Photoshop CS6 (Adobe). Fluorescent-labeled specimens were analyzed with a SP5 confocal laser microscope (Leica, Germany) and processed by the ImageJ software version 2.0.0-rc-42/1.50d (Wayne Rasband, NIH) [83]. Figure plates were arranged with Illustrator CS6 (Adobe).

Availability of data and materials

All newly determined sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MN431422–MN431430.

References

Zimmer RL. Phoronids, Brachiopods, and Bryozoans, the Lophophorates. In: Gilbert SF, Raunio AM, editors. Embryology: constructing the organism. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1997.

Vellutini BC, Martín-Durán JM, Hejnol A. Cleavage modification did not alter blastomere fates during bryozoan evolution. BMC Biol. 2017;15(1):33.

Freeman G. A developmental basis for the Cambrian radiation. Zool Sci. 2007;24(2):113–22.

Martín-Durán J, Passamaneck YJ, Martindale MQ, Hejnol A. The developmental basis for the recurrent evolution of deuterostomy and protostomy. Nat Ecol Evol. 2016;1(1):5.

Gąsiorowski L, Hejnol A. Hox gene expression during the development of the phoronid Phoronopsis harmeri. Biorxiv. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1101/799056.

Giribet G, Dunn CW, Edgecombe GD, Hejnol A, Martindale MQ, Rouse GW. Assembling the spiralian tree of life. In: Telford MJ, Littlewood DTJ, editors. Animal evolution: genes, genomes, fossils and trees. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 52–64.

Kocot KM, Struck TH, Merkel J, Waits DS, Todt C, Brannock PM, Weese DA, Cannon JT, Moroz LL, Lieb B, et al. Phylogenomics of lophotrochozoa with consideration of systematic error. Syst Biol. 2017;66(2):256–82.

Laumer CE, Bekkouche N, Kerbl A, Goetz F, Neves RC, Sorensen MV, Kristensen RM, Hejnol A, Dunn CW, Giribet G, et al. Spiralian phylogeny informs the evolution of microscopic lineages. Curr Biol. 2015;25(15):2000–6.

Laumer CE, Fernandez R, Lemer S, Combosch D, Kocot KM, Riesgo A, Andrade SCS, Sterrer W, Sorensen MV, Giribet G. Revisiting metazoan phylogeny with genomic sampling of all phyla. Proc Biol Sci. 2019;286(1906):20190831.

Marletaz F, Peijnenburg K, Goto T, Satoh N, Rokhsar DS. A new spiralian phylogeny places the enigmatic arrow worms among gnathiferans. Curr Biol. 2019;29(2):312–8.

Santagata S, Cohen BL. Phoronid phylogenetics (Brachiopoda; Phoronata): evidence from morphological cladistics, small and large subunit rDNA sequences, and mitochondrial cox1. Zool J Linnean Soc. 2009;157(1):34–50.

Kowalevsky A. Anatomy and developmental history of Phoronis. Mém Acad Imp Sci St-Pétersbourg. 1867;11:1–41.

Silén L. Developmental biology of Phoronidea of the Gullmar fiord area (west coast of Sweden). Acta Zool. 1954;35(3):215–57.

Brooks WK, Cowles RP. Phoronis architecta: its life history, anatomy, and breeding habits. Washington: National Academy of Sciences; 1905.

de Selys-Longchamps MAG. Recherches sur le developpement des Phoronis. Arch Biol. 1902;18:495–597.

Emig CC. Embryology of phoronida. Am Zool. 1977;17(1):21–37.

Freeman G. The bases for and timing of regional specification during larval development in Phoronis. Dev Biol. 1991;147(1):157–73.

Freeman G, Martindale MQ. The origin of mesoderm in phoronids. Dev Biol. 2002;252(2):301–11.

Herrmann K. Ontogenesis of Phoronis muelleri (Tentaculata) with a special sight for differentiation of mesoderm and phylogenesis of coelom. Zool Jb Anat. 1986;114(4):441–63.

Ikeda I. Observations on the development: structure and metamorphosis of Actinotrocha. J Coll Sci Teach. 1901;13:507–91.

Malakhov VV, Temereva EN. Embryonic development of the phoronid Phoronis ijimai. Russ J Mar Biol. 2000;26(6):412–21.

Masterman A. On the diplochorda. J Cell Sci. 1898;40:281–366.

Pennerstorfer M, Scholtz G. Early cleavage in Phoronis muelleri (Phoronida) displays spiral features. Evol Devel. 2012;14(6):484–500.

Rattenbury JC. The embryology of Phoronopsis viridis. J Morph. 1954;95(2):289–349.

Temereva EN, Malakhov VV. Embryogenesis and larval development of Phoronopsis harmeri Pixell, 1912 (Phoronida): dual origin of the coelomic mesoderm. Invert Rep Dev. 2007;50(2):57–66.

Zimmer RL. Mesoderm proliferation and formation of the protocoel and metacoel in early embryos of Phoronis vancouverensis (Phoronida). Zool Jb Anat. 1980;103:219–33.

Zimmer RL. Reproductive biology and development of Phoronida. Ann Arbor: University of Washington; 1964.

Herrmann K. Phoronis muelleri (Tentaculata)-Embryonalentwicklung. Göttingen: Publikationen zu Wissenschaftlichen Filmen; 1981.

Emig CC. Observations et discussions sur le developpement embryonnaire des Phoronida. Z Morph Tiere. 1974;77(4):317–35.

Foettinger A. Note sur la formation du mesoderme dans la larve de Phoronis hippocrepia. Arch Biol Paris. 1882;3:679.

Siewing R. Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Entwicklungsgeschichte der Tiere. Hamburg: Paul Parey; 1969.

Cori CJ. Phoronidea. In: Bronns Klassen und Ordnungen des Tierreichs 4. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft; 1939.

Temereva EN, Malakhov VV. Embryogenesis in phoronids. Invert Zool. 2012;9(1):1–39.

Emig CC. The biology of Phoronida. Adv Mar Biol. 1982;19:1–89.

Zimmer RL. Morphological and developmental affinities of the lophophorates. In: Larwood GP, editor. Living and fossil Bryozoa. London: Academic Press; 1973. p. 593–9.

Bartolomaeus T. Ultrastructure and formation of the body cavity lining in Phoronis muelleri (Phoronida, Lophophorata). Zoomorphology. 2001;120(3):135–48.

Temereva EN, Malakhov VV. The morphology of the Phoronid Phoronopsis harmeri. Russ J Mar Biol. 2001;27(1):21–30.

Arendt D, Technau U, Wittbrodt J. Evolution of the bilaterian larval foregut. Nature. 2001;409(6816):81.

Lowe CJ, Wu M, Salic A, Evans L, Lander E, Stange-Thomann N, Gruber CE, Gerhart J, Kirschner M. Anteroposterior patterning in hemichordates and the origins of the chordate nervous system. Cell. 2003;113(7):853–65.

Marlow H, Tosches MA, Tomer R, Steinmetz PRH, Lauri A, Larsson T, Arendt D. Larval body patterning and apical organs are conserved in animal evolution. BMC Biol. 2014;12(1):7.

Santagata S, Resh C, Hejnol A, Martindale MQ, Passamaneck YJ. Development of the larval anterior neurogenic domains of Terebratalia transversa (Brachiopoda) provides insights into the diversification of larval apical organs and the spiralian nervous system. EvoDevo. 2012;3(1):3.

Steinmetz PRH, Urbach R, Posnien N, Eriksson J, Kostyuchenko RP, Brena C, Guy K, Akam M, Bucher G, Arendt D. Six3 demarcates the anterior-most developing brain region in bilaterian animals. EvoDevo. 2010;1(1):14.

Annunziata R, Perillo M, Andrikou C, Cole AG, Martinez P, Arnone MI. Pattern and process during sea urchin gut morphogenesis: the regulatory landscape. Genesis. 2014;52(3):251–68.

Hejnol A, Martín-Durán JM. Getting to the bottom of anal evolution. Zool Anz. 2015;256:61–74.

Boyle MJ, Yamaguchi E, Seaver EC. Molecular conservation of metazoan gut formation: evidence from expression of endomesoderm genes in Capitella teleta (Annelida). EvoDevo. 2014;5(1):39.

Martín-Durán J, Janssen R, Wennberg S, Budd GE, Hejnol A. Deuterostomic development in the protostome Priapulus caudatus. Curr Biol. 2012;22(22):2161–6.

Oliveri P, Walton KD, Davidson EH, McClay DR. Repression of mesodermal fate by foxa, a key endoderm regulator of the sea urchin embryo. Development. 2006;133(21):4173–81.

Passamaneck YJ, Hejnol A, Martindale MQ. Mesodermal gene expression during the embryonic and larval development of the articulate brachiopod Terebratalia transversa. EvoDevo. 2015;6:10.

Patient RK, McGhee JD. The GATA family (vertebrates and invertebrates). Curr Opin Gen Dev. 2002;12(4):416–22.

Technau U, Scholz CB. Origin and evolution of endoderm and mesoderm. Int J Dev Biol. 2003;47(7–8):531–9.

Cho S-J, Vallès Y, Giani VC Jr, Seaver EC, Weisblat DA. Evolutionary dynamics of the wnt gene family: a lophotrochozoan perspective. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(7):1645–58.

Jackson DJ, Meyer NP, Seaver E, Pang K, McDougall C, Moy VN, Gordon K, Degnan BM, Martindale MQ, Burke RD. Developmental expression of COE across the Metazoa supports a conserved role in neuronal cell-type specification and mesodermal development. Dev Genes Evol. 2010;220(7–8):221–34.

Layden MJ, Meyer NP, Pang K, Seaver EC, Martindale MQ. Expression and phylogenetic analysis of the zic gene family in the evolution and development of metazoans. EvoDevo. 2010;1(1):12.

Martín-Durán JM, Pang K, Børve A, Semmler Lê H, Furu A, Cannon JT, Jondelius U, Hejnol A. Convergent evolution of bilaterian nerve cords. Nature. 2018;553(7686):45.

Martín-Durán JM, Vellutini BC, Hejnol A. Embryonic chirality and the evolution of spiralian left–right asymmetries. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2016;371(1710):20150411.

Campbell K, Whissell G, Franch-Marro X, Batlle E, Casanova J. Specific GATA factors act as conserved inducers of an endodermal-EMT. Dev Cell. 2011;21(6):1051–61.

Wu LH, Lengyel JA. Role of caudal in hindgut specification and gastrulation suggests homology between Drosophila amnioproctodeal invagination and vertebrate blastopore. Development. 1998;125(13):2433–42.

Cole AG, Rizzo F, Martinez P, Fernandez-Serra M, Arnone MI. Two ParaHox genes, SpLox and SpCdx, interact to partition the posterior endoderm in the formation of a functional gut. Development. 2009;136(4):541–9.

Lee PY, Davidson EH. Expression of Spgatae, the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus ortholog of vertebrate GATA4/5/6 factors. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;5(2):161–5.

Boyle MJ, Seaver EC. Expression of FoxA and GATA transcription factors correlates with regionalized gut development in two lophotrochozoan marine worms: Chaetopterus (Annelida) and Themiste lageniformis (Sipuncula). EvoDevo. 2010;1(1):2.

de Rosa R, Prud’homme B, Balavoine G. Caudal and even-skipped in the annelid Platynereis dumerilii and the ancestry of posterior growth. Evol Dev. 2005;7(6):574–87.

Martín-Durán J, Vellutini BC, Hejnol A. Evolution and development of the adelphophagic, intracapsular Schmidt’s larva of the nemertean Lineus ruber. EvoDevo. 2015;6:28.

Ayanbule F, Belaguli NS, Berger DH. GATA factors in gastrointestinal malignancy. World J Surg. 2011;35(8):1757–65.

Besnard V, Wert SE, Hull WM, Whitsett JA. Immunohistochemical localization of Foxa1 and Foxa2 in mouse embryos and adult tissues. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;5(2):193–208.

Zorn AM, Wells JM. Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:221–51.

Hejnol A, Martindale MQ. Acoel development indicates the independent evolution of the bilaterian mouth and anus. Nature. 2008;456(7220):382.

Sinigaglia C, Busengdal H, Leclere L, Technau U, Rentzsch F. The bilaterian head patterning gene six3/6 controls aboral domain development in a cnidarian. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(2):e1001488.

Wei Z, Yaguchi J, Yaguchi S, Angerer RC, Angerer LM. The sea urchin animal pole domain is a Six3-dependent neurogenic patterning center. Development. 2009;136(7):1179–89.

Poustka AJ, Kühn A, Groth D, Weise V, Yaguchi S, Burke RD, Herwig R, Lehrach H, Panopoulou G. A global view of gene expression in lithium and zinc treated sea urchin embryos: new components of gene regulatory networks. Genome Biol. 2007;8(5):R85.

Perry KJ, Lyons DC, Truchado-Garcia M, Fischer AH, Helfrich LW, Johansson KB, Diamond JC, Grande C, Henry JQ. Deployment of regulatory genes during gastrulation and germ layer specification in a model spiralian mollusc Crepidula. Dev Dyn. 2015;244(10):1215–48.

Zaffran S, Das G, Frasch M. The NK-2 homeobox gene scarecrow (scro) is expressed in pharynx, ventral nerve cord and brain of Drosophila embryos. Mech Dev. 2000;94(1–2):237–41.

Takacs CM, Moy VN, Peterson KJ. Testing putative hemichordate homologues of the chordate dorsal nervous system and endostyle: expression of NK2. 1 (TTF-1) in the acorn worm Ptychodera flava (Hemichordata, Ptychoderidae). Evol Dev. 2002;4(6):405–17.

Venkatesh TV, Holland ND, Holland LZ, Su M-T, Bodmer R. Sequence and developmental expression of amphioxus AmphiNk2-1: insights into the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate thyroid gland and forebrain. Dev Genes Evol. 1999;209(4):254–9.

Holland LZ. Body-plan evolution in the Bilateria: early antero-posterior patterning and the deuterostome–protostome dichotomy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10(4):434–42.

Lengyel JA, Iwaki DD. It takes guts: the Drosophila hindgut as a model system for organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;243(1):1–19.

McGhee JD. Homologous tails? Or tales of homology? BioEssays. 2000;22(9):781–5.

Temereva EN. The digestive tract of actinotroch larvae (Lophotrochozoa, Phoronida): anatomy, ultrastructure, innervations, and some observations of metamorphosis. Can J Zool. 2010;88(12):1149–68.

Freeman G. Regional specification during embryogenesis in the articulate brachiopod Terebratalia. Dev Biol. 1993;160(1):196–213.

Freeman G. Regional specification during embryogenesis in the craniiform brachiopod Crania anomala. Dev Biol. 2000;227(1):219–38.

Freeman G. Regional specification during embryogenesis in Rhynchonelliform brachiopods. Dev Biol. 2003;261(1):268–87.

Marsden JR. Phoronidea from the Pacific coast of North America. Can J Zool. 1959;37(2):87–111.

Hejnol A. In situ protocol for embryos and juveniles of Convolutriloba longifissura. Protocol Exch. 2008;7:20.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Orus Alcalde and Ludwik Gasiorowski from the Hejnol group for contributing to animal collection and spawning. We also thank Kevin Uhlinger for his help with rearing larvae, and Paul Bump from the Lowe lab and Karl Menard from Bodega Bay Marine Lab for their help with collecting adults. We thank Chema Martin-Duran for reading the manuscript. We also gratefully thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sars Centre core budget and the European Research Council Community’s Framework Program Horizon 2020 (2014–2020) ERC Grant Agreement 648861 to AH and an NSF Grant 0531558 to MQM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA, CL, MQM and AH designed the study. CL made and provided the transcriptome. YP and CA performed the collections and CA conducted the experiments. CA, CL, MQM and AH analyzed the data. CA and AH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Studies of phoronids do not require ethics approval or consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Orthology analysis. Putative orthologous sequences of genes of interest were identified by tBLASTx search against the transcriptome of Ph. harmeri. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is supporting orthology. Names of genes or proteins, if available, follow the name of organism(s). Ph. harmeri sequences are highlighted in red. Ph, Phoronopsis harmeri; Na, Novocrania anomala; Tt, Terebratalia transversa; Mm, Membranipora membranacea; Hs, Homo sapiens; Xl, Xenopus laevis; Xt, Xenopus tropicalis; Dr, Danio rerio; Mm, mus musculus; Gg, Gallu gallus; Sk, Saccoglossus kowalevskii; Pf, Ptychodera flava; Sp, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus; Pl, Paracentrotus lividus; Lv, Lytechinus variegatus; Am, Asterina miniata; At, Archaster typicus; Ci, Ciona intestinalis; Hl, Halocynthia roretzi; Od, Oikopleura dioica; Bf, Branchiostoma floridae; Sm, Strigamia maritima; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Tc, Tribolium castaneum; Lg, Lottia gigantea; Euprymna; Cf, Crepidula fornicata; Ml, Macrostomum lignano; Sm, Schmidtea mediterranea; Spoly, Schmidtea polychroa; Pv, Prostheceraeus vittatus; Gt, Girardia tigrina; Ct, Capitella teleta; Of, Owenia fusiformis; Pd, Platynereis dumerilii; He, Hydroides elegans; Tt, Tubifex tubifex; Chaetopterus; Phascolion; Ap, Apis mellifera; Pc, Priapulus caudatus; Achaearanea; Bm, Bombyx mori; Ha, Helicoverpa armigera; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Hydractinia; Hydra; Cr, Cladonema radiatum; Aa, Aurelia aurita; Pc, Podocoryna carnea; Ms, Meara stichopi; Cm, Convolutriloba macropyga; Ta, Trichoplax adhaerens; Sc, Sycon ciliatum; Pb, Pleurobrachia bachei; Diplosoma.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrikou, C., Passamaneck, Y.J., Lowe, C.J. et al. Molecular patterning during the development of Phoronopsis harmeri reveals similarities to rhynchonelliform brachiopods. EvoDevo 10, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-019-0146-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-019-0146-1