Abstract

This review covers basic aspects of histone modification and the role of posttranslational histone modifications in the development of allergic diseases, including the immune mechanisms underlying this development. Together with DNA methylation, histone modifications (including histone acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, etc.) represent the classical epigenetic mechanisms. However, much less attention has been given to histone modifications than to DNA methylation in the context of allergy. A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to provide an unbiased and comprehensive update on the involvement of histone modifications in allergy and the mechanisms underlying this development. In addition to covering the growing interest in the contribution of histone modifications in regulating the development of allergic diseases, this review summarizes some of the evidence supporting this contribution. There are at least two levels at which the role of histone modifications is manifested. One is the regulation of cells that contribute to the allergic inflammation (T cells and macrophages) and those that participate in airway remodeling [(myo-) fibroblasts]. The other is the direct association between histone modifications and allergic phenotypes. Inhibitors of histone-modifying enzymes may potentially be used as anti-allergic drugs. Furthermore, epigenetic patterns may provide novel tools in the diagnosis of allergic disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the last few decades, there has been a substantial increase in the prevalence of allergic diseases in the industrialized countries [1,2,3]. Since this change could not be explained by a rather stable population genetic profile [2,3,4], increased exposure to harmful and reduced exposure to protective epigenetically-mediated environmental factors have been considered, at least in part, as a possible explanation for this epidemiological phenomenon [5,6,7,8,9]. While DNA methylation has been extensively studied as the epigenetic mechanism involved in the etiopathogenesis of allergic disorders, posttranslational histone modifications, another important classical epigenetic mechanism, have not been as widely investigated and discussed because it is not considered as important as DNA methylation [5,6,7, 10]. The review firstly describes the (bio-) chemical basics of epigenetic histone modifications. This is followed by an assessment of recent evidence that supports a role for histone modifications in the epigenetic regulation of the pathogenesis of allergy and related disorders, together with a description of the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms.

Main text

Histone modifications: the basics

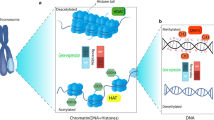

Similarly to DNA methylation, posttranslational histone modifications do not affect DNA nucleotide sequence but can modify its availability to the transcriptional machinery. Although histone modifications play also other roles, such as histone phosphorylation, best known for its contribution to DNA repair in response to cell damage, this review deals primarily with general mechanisms of histone modifications in the context of their role in epigenetic modulation of gene expression. Several types of histone modifications are known, amongst which acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination are the best studied and most important in terms of the regulation of chromatin structure and (transcriptional) activity [11,12,13,14,15]. In general, histone modifications are catalyzed by specific enzymes that act, predominantly, but not exclusively (e.g. some types of histone phosphorylation), at the histone N-terminal tails involving amino acids such as lysine or arginine as well as serine, threonine, tyrosine, etc. Histone acetylation usually leads to higher gene expression. This may not always be the case for histone H4 [16,17,18]. Histone methylation in turn has either transcriptionally permissive or repressive character, depending on the location of targeted amino acid residues in the histone tail and/or the number of modifying (e.g. methyl) groups added [5, 6, 14, 15, 19, 20]. Table 1 summarizes the various forms of histone modifications appearing in this review along with their effects on gene transcriptional activity.

Histone acetylation

Histone acetylation status is regulated by two groups of enzymes exerting opposite effects, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). HATs catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to an amino acid group of the target lysine residues in the histone tails, which leads to the removal of a positive charge on the histones, weakening the interaction between histones and (negatively charged phosphate groups of) DNA. This in turn typically makes the chromatin less compact and thus more accessible to the transcriptional machinery. HDACs remove acetyl groups from histone tail lysine residues and thereby work as repressors of gene expression [5, 14, 21,22,23,24].

HATs are classified into five (or sometimes six) families. The GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) family comprises KAT2A and KAT2B enzymes. They are involved in acetylation of histones and transcription factors and thus cell cycle regulation, and DNA replication and repair [25, 26]. Moreover, these enzymes have been recently identified to be important for centrosome function as well [27]. The MYST family is in turn composed of KAT6A/MOZ/MYST3, KAT6B/MORF/MYST4, KAT7/HBO1/MYST2, KAT8/hMOF/MYST1, and KAT5/Tip60. It contributes to transcription regulation and is also responsible for DNA repair [28,29,30]. Interestingly, autoacetylation of MYST family protein enzymes participates in their regulation, which makes them distinct from other acetyltransferases, drawing at the same time similarities to the phosphoregulation of protein kinases [31, 32]. The other HAT families are much smaller. KAT3A and KAT3B enzymes belong to p300/CBP family, and KAT4/TAF1/TBP and KAT12/TIFIIIC90 are members of the general transcriptional factor-related HAT family [23, 28, 33]. Steroid receptor co-activators family comprises KAT13A/SRC1, KAT13B/SCR3/AIB1/ACTR, KAT13C/p600, and KAT13D/CLOCK [23, 34]. Finally, KAT1/HAT1 and HAT4/NAA60 are cytoplasmic HATs [23].

Eighteen enzymes belonging to the HDAC superfamily have been identified. They are further subdivided into four classes, including class I (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8), class IIa (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7, and HDAC9), class IIb (HDAC6 and HDAC10), class III, so-called sirtuins (SIRTs; SIRT 1–7; enzymes evolutionally and mechanistically different from the other HDACs), and class IV (HDAC11) [35,36,37]. Class I HDACs are characterized by a ubiquitous nuclear expression in all tissues, class IIb HDACs are present both in the nucleus and cytoplasm, and class IIa HDACs show mainly cytosolic localization. Not much is known about HDAC11, and sirtuins which localize in nucleus, cytosol and/or mitochondria [36].

Histone methylation

Histone methylation is mediated by histone methyltransferases (HMTs), including lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), and histone demethylation by histone demethylases (HDMs).

Whereas acetylation of the histone lysine affects the electrical charge of the histones and thus their interaction with DNA, methylation of histone lysine or arginine does not affect this electrostatic bond, but instead indirectly influences the recruitment and binding of different regulatory proteins to chromatin [19, 38, 39]. HMTs can transfer up to three methyl groups from the cofactor S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) to lysine or arginine residues of the histones [19, 38]. More than 50 human KMTs are known at the moment, which, based on their catalytic domain sequence, can be further subdivided into the SET domain-containing and the DOT1-like protein family, the latter having only one representative in humans, with a catalytic domain structurally more similar to the PRMTs [19, 38, 39]. KMTs are more specific than HATs and they generally target a specific lysine residue. Methylation of H3K4 residue (for the description of histone modifications including their location, character and effect on transcription, please, refer to Table 1) is mediated in mammals by KMTs such as KMT2A/MLL1, KMT2A/MLL2, KMT2F/hSET1A, KMT2G/hSET1B, or KMT2H/ASH1. Examples of KMTs responsible for H3K9 methylation include KMT1A/SUV39H1, KMT1B/SUV39H2, KMT1C/G9a, or KMT1D/EuHMTase/GLP. H3K36 methylation is catalyzed by e.g. KMT3B/NSD1, KMT3C/SMYD2, or KMT3A/SET(D)2. KMT6A/EZH2 methylates H3K27, andKMT4/DOT1L targets H3K79. Etc. [19, 38, 39].

Based on the catalytic mechanism and sequence homology, HDMs can be divided into two classes. Firstly, amine-oxidase type lysine-specific demethylases (LSDs or KDM1 s), including KDM1A/LSD1/AOF2 and KDM1B/LSD2/AOF1. These remove the methyl groups from mono- and dimethylated H3K4. Secondly, the JumonjiC (JMJC) domain-containing HDMs, in turn, catalyze the demethylation of mono-, di-, and trimethylatedlysine residues at various histone amino acid residues. Over thirty members of this group can be further subdivided, based on the JMJC domain homology, into seven/eight subfamilies (KDM2–7/8) [19, 38,39,40,41].

Histone phosphorylation

Histone phosphorylation status is controlled by two types of enzymes having opposing modes of action. While kinases add phosphate groups, phosphatases remove the phosphates [13, 15]. At least three functions of phosphorylated histones are known, DNA damage repair, the control of chromatin compaction associated with mitosis and meiosis, and the regulation of transcriptional activity (similar to histone acetylation) [13, 15]. In comparison to histone acetylation and methylation, histone phosphorylation works in conjunction with other histone modifications, establishing the platform for mutual interactions between them. This cross-talk results in a complex downstream regulation of chromatic status and its consequences [13, 15, 42]. For example, histone H3 phosphorylation (specifically H3S10ph) can directly affect acetylation levels at two amino acid residues of the same histone (H3K9ac and H3K14ac) [43, 44]. Furthermore, H3S10ph can induce transcriptional activation by interaction with H4K16ac [42].

Histone ubiquitination

Protein ubiquitination is an important post-translational modification that regulates almost every aspect of cellular function in many cell signaling pathways in eukaryotes. Ubiquitin is an 8.5 kD protein which is conjugated to substrate proteins by the ubiquitin–proteasome system thereby regulating the stability and turnover of the target proteins. Histone ubiquitination is carried out by histone ubiquitin ligases and can be removed by ubiquitin-specific peptidases, the latter known as deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [45,46,47]. Monoubiquitination has a critical role in protein translocation, DNA damage signaling, and transcriptional regulation. Histone 2A monoubiquitination (H2Aub) is more often associated with gene silencing. Monoubiquitination of histone 2B (H2Bub) is typically correlated with transcription activation. Polyubiquitination marks the protein for degradation or activation in certain signaling pathways [45,46,47,48]. Similarly to histone phosphorylation, there is also cross-talk between histone ubiquitination and other histone modifications [46,47,48]. For instance, monoubiquitination of histone H3 is able to induce acetylation of the same histone [49].

Epigenetic readers

In addition to epigenetic writers, i.e. enzymes adding epigenetic marks on histones (HATs, HMTs/KMTs, PRMTs, kinases, ubiquitin ligases) and epigenetic erasers (HDACs, HDMs/KDMs, phosphatases, DUBs), there are also epigenetic readers, which are the molecules that recognize and bind to the epigenetic marks created by writers, thereby determining their functional consequences. They include proteins containing bromodomains, chromodomains, or Tudor domains [50, 51]. Some enzymes with primary activities different from epigenetic reading possess bromodomains as well, for example certain HATs [51].

Systematic search: methodology

In order to cover the area of interest, a systematic literature search was conducted (Fig. 1). In brief, On January 23, 2017, the PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) was searched by using the input “(allergy OR atopy OR asthma OR dermatitis OR eczema OR food allergy OR rhinitis OR conjunctivitis) AND (histone modifications OR histone modification OR histone acetylation OR histone methylation OR histone phosphorylation OR histone ubiquitination)”, restricting the results with “5 years” (“Publication dates”) and “Humans” (“Species”) filters, which yielded a total of 170 hits. These were subsequently subjected to full text-based screening to exclude articles not reporting original data (reviews, editorials, commentaries, etc.), which resulted in elimination of 54 publications. From the remaining 116 papers, a further 72 were excluded as not being directly or at least indirectly relevant to the topic of the present review (not reporting data on histone modifications, reporting histone modification data but not in the context of allergic or related disorders, or both). The remaining 44 articles were divided into two groups. The group that met the primary selection criterion contained 17 papers reporting the data on the role of histone modifications in allergic diseases obtained in material collected from allergic subjects and thus directly relevant to allergies is presented in Table 2. Another 27 articles of potential interest comprised the additional group (Table 3). These did not necessarily target allergic disorders but allergy-like diseases or related conditions, did not report histone modification data obtained in primary human cells/tissues, or indeed a combination of those. This included also those reporting data on epigenetic mechanisms likely playing a role in allergies but not directly related to/associated with this group of diseases.

Systematic search: review

Epigenetic mechanisms are thought to play an important regulatory role in allergic inflammation and the development of allergic disorders. DNA methylation is the classical epigenetic modification that has been most widely studied in this context. However, histone modifications, which contribute to the lineage commitment, differentiation and maturation of immune cells, including those strongly involved in allergic inflammation such as CD4+ T-helper (Th) cells, are likely to play a crucial role in the predisposition to developing atopic diseases as well as in the effector phase of allergic inflammation [5, 6, 10, 52, 53]. Indeed, our systematic search identified a number of recent studies that sought to define the relationships between histone modifications and allergic inflammation or related immune mechanisms, and/or allergic diseases or disorders sharing some of the pathophysiology. The results reported in those 44 original articles are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Several studies investigated the relationships between histone modifications in airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) and the respiratory tract allergic inflammatory disease. For instance, increased binding of bromodomain-containing HATs [E1A binding protein p300 (p300) and p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF)] accompanied by significantly higher H3ac levels (specifically H3K18ac) at the C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) gene (CXCL8) promoter were observed in ASMCs obtained from asthmatics compared to healthy controls [54]. Furthermore, treatment of cultured cells with bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) protein inhibitors reduced CXCL8 secretion [54]. The application of BET bromodomain mimics reduced in turn fetal calf serum plus transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) -induced ASMC proliferation and interleukin 6 (IL-6) gene (IL6) and CXCL8 expression, with the required dose depending on asthma severity of cell donor [55]. On the other hand, no differences in H3ac and H4ac levels at the cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COX2) gene (COX2) between the asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASMCs were detected, regardless of whether they were stimulated with proinflammatory cytokines [56]. Although asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASMCs did not differ in their H3ac or H4ac levels at the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) locus (VEGFA), the cells obtained from affected individuals displayed slightly but consistently higher H3K4me3 and a low H3K9me3 levels [57]. Moreover, treatment with an inhibitor of a HMT (HMTi), euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2 (G9a), increased VEGF expression in non-asthmatic ASMCs to near asthmatic levels [57].

Histone modifications at several of the above-mentioned loci contribute also to the pathophysiology of some other inflammatory disorders of the lung. For example, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 levels at the COX2 promoter were found to be substantially higher in primary human fibroblasts isolated from lung tissue of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients compared to non-IPF fibroblasts. This was accompanied by the recruitment of HMTs, G9a and enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2) [58]. Interestingly, after treatment with G9a or EZH2 inhibitors, the levels of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 markedly decreased and H3ac and H4ac levels increased at the COX2 promoter [58]. Several other studies observed the involvement of histone modifications in the regulation of gene expression in (human) IPF lung (myo-) fibroblasts, the effects of which were sensitive to HDAC inhibitor (HDACi) treatment [59,60,61]. Histone acetylation and/or methylation in (myo-) fibroblasts were also demonstrated to regulate expression of the loci involved in the pathogenesis of nasal chronic rhinosinusitis and polyposis, such as prostaglandin E receptor 2 (EP2) gene (PTGER2) [62]. Furthermore, HDACi treatment influenced HDAC expression and histone acetylation at several loci, thus affecting nasal polyp myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix production [63, 64]. Finally, although no differences in ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 (ADAM33) gene (ADAM33) expression were observed between asthmatic and healthy control bronchial fibroblasts, treatment with TGF-β suppressed ADAM33 mRNA expression through chromatin condensation related to deacetylation of H3ac, demethylation of H3K4, and hypermethylation of H3K9 at the ADAM33 promoter [65]. Asthmatic and non-asthmatic histone acetylation levels were compared also in alveolar epithelial cells [66]. Global H3K18ac and H3K9me3 levels were higher in cells from asthmatics, which was also the case for gene-specific H3K18ac (but not H3K9me3) around transcription start sites of the loci encoding tumor protein p63 (TP63; ∆Np63 isoform), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) [66]. The latter effect was ablated upon HDACi treatment [66].

Several studies were conducted on the biology of monocytes, the mechanisms of epigenetic modulation controlling production of cytokines, and their role in the onset/severity of allergic diseases. H4ac levels at the glucocorticoid response element upstream of the dual specificity phosphatase 1 gene (DUSP1) encoding for MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) substantially increased in dexamethasone-treated cells obtained from both steroid-sensitive and steroid-resistant asthmatics patients [67]. Furthermore, preincubation with calcitriol led to a significant enhancement of the dexamethasone-induced H4ac, with higher H4ac levels observed in monocytes obtained from steroid-sensitive than those from steroid-resistant individuals [67]. The involvement of histone acetylation or phosphorylation in regulation of gene expression in monocytes/macrophages was also demonstrated for C–C motif chemokine ligand 2/17/22 (CCL2/17/22), CXCL8, or IL6 loci [68,69,70,71]. In addition, in monocytes, histone modification changes were susceptible to pharmacological modification ex vivo, demonstrated by the effect of HDACi on CXCL8 H4ac levels [70].

Several studies have focused on T-cells. For example, differences in H3ac and H4ac levels at the interleukin 13 (IL-13) gene (IL13) that were observed in CD4+ T-cells from children with allergic asthma and healthy controls correlated with serum IL-13 concentrations [72]. Differential enrichment of H3K4me2 in 200 cis-regulatory/enhancer regions in naïve, Th1, and Th2 CD4+ T-cells was observed between asthmatic and non-asthmatic subjects. Moreover, 163 of those 200 asthma-associated enhancers were Th2-specific and 84 of them contained binding sites for transcription factors involved in T cell differentiation [e.g. GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3), T-box 21 (TBX21) and RUNX3] [73]. Most of the other studies identified by our literature search were also supportive for the importance of histone modifications, such as acetylation and methylation, in (CD4+) T-cell biology and/or related pathophysiology of allergic disorders [74,75,76,77,78].

Some prenatal dietary exposures, previously demonstrated to modulate the infant’s immune responses and/or risk of allergy development in offspring [79,80,81,82], have recently been shown to be associated with the alterations in histone acetylation profiles in neonatal cells. For instance, cord blood (CB) CD4+ T-cells obtained from children born from mothers with highest serum folate levels during pregnancy were characterized by significantly higher histone H3ac and H4ac levels at the GATA3 gene (GATA3) promoter, markedly lower H4ac levels at the analogous region of the interferon gamma (IFNγ) gene (IFNG), and significantly higher interleukin-9 (IL-9) gene (IL9) promoter H4ac levels when compared to the lowest folate level group [83]. In CB CD4+ T-cells obtained from newborns of mothers supplemented with fish oil (ω − 3 fatty acids) during pregnancy in turn, significantly higher H3ac levels were observed at the protein kinase C zeta (PKCζ) gene (PRKCZ) and IFNG locus, and lower H3/H4ac levels at the IL-13 and TBX21 genes (IL13 and TBX21, respectively) [84]. The infants from the fish oil-supplemented women were found to have lower risk of developing allergic diseases [81, 82].

Both passive (prenatal and postnatal) and active tobacco smoke exposures are a well-known extrinsic factors affecting the risk of allergic disorders, especially asthma, and this effect was found to be associated with (and thus is thought to be at least partly mediated by) changes in DNA methylation patterns [5, 6]. Exposure to passive smoking diminished corticosteroid sensitivity of alveolar macrophages obtained from children with severe asthma and was accompanied by lower HDAC2 expression and activity. This possibly explains the unfavorable effect [85] and suggests that histone modifications, specifically histone acetylation, are also involved.

The text in this review has been selective in discussing the field and the reader is advised to consult Tables 2 and 3 for a more comprehensive appreciation of the wider literature review.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The results of our systematic literature assessment demonstrate a growing interest in the contribution of histone modifications in regulating the development of allergic disorders and, at the same time, provide evidence supporting this contribution. The role of histone modification is manifested at least at two levels. One involves the regulation of cells participating in the allergic inflammatory reaction, namely the inflammatory cells, T cells and macrophages, and the local tissue cells, such as (myo-) fibroblasts, which contribute to remodeling of airways. The other is the direct relationships between histone modifications and allergic phenotypes.

Furthermore, experimental observations of effects of histone marks modifying substances, e.g. HDACis or HMTis, suggest the potential application of histone epigenome editing in the treatment of allergies [35, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. Such therapies do not need to be simply restricted to histone-modifying enzyme inhibitors but may also include more targeted approaches based on e.g. CRISPR/dCas9 system [6, 92] or antisense molecules [6, 93,94,95]. Others include nutrients [71] or even bio-physical interventions [96]. Finally, also diagnostic/prognostic tools for allergic traits based on epigenetic patterns/signatures could possibly be developed in future, as suggested by several studies on DNA methylation [6, 97,98,99].

This review provides a systematic update of the current knowledge on the contribution of histone modifications to allergic inflammation and disorders.

Abbreviations

- ADAM33 :

-

ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 (ADAM33) gene

- ASMC:

-

airway smooth muscle cell

- BET (proteins):

-

bromodomain and extra-terminal (proteins)

- CB:

-

cord blood

- CCL2/17/22 :

-

C–C motif chemokine ligand 2/17/22 gene

- COX2 :

-

cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COX2) gene

- CXCL8 :

-

C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) gene

- DOT1L (human KMT):

-

DOT1-like (human KMT)

- DUB:

-

deubiquitinating enzyme

- DUSP1 :

-

dual specificity phosphatase 1 (MAPK phosphatase 1; MKP-1) gene

- EGFR :

-

epidermal growth factor receptor gene

- EZH2:

-

enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit

- FCS:

-

fetal calf serum

- GATA3 :

-

GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) gene

- GNAT (family):

-

GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (family)

- HAT:

-

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC:

-

histone deacetylase

- HDACi:

-

HDAC inhibitor

- HDM:

-

histone demethylase

- HMT:

-

histone methyltransferase

- HMTi:

-

HMT inhibitor

- IL6/9/13 :

-

interleukin 6/9/13 (IL-6/-9/-13) gene

- IFNG :

-

interferon gamma (IFNγ) gene

- IPF:

-

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- JMJC (domain):

-

JumonjiC (domain)

- KMT:

-

lysine methyltransferase

- LSD/KDM1:

-

(amine-oxidase type) lysine-specific demethylase

- PRMT:

-

arginine methyltransferase

- PCAF:

-

p300/CBP-associated factor

- PRKCZ :

-

protein kinase C zeta (PKCζ) gene

- PTGER2 :

-

prostaglandin E receptor 2 (EP2) gene

- p300:

-

E1A binding protein p300

- SAM:

-

S-adenosyl-l-methionine

- STAT6 :

-

signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 gene

- TBX21 :

-

T-box 21 (TBX21) gene

- TGF-β:

-

transforming growth factor beta

- Th (cell):

-

helper T-cells/T-helper (cell)

- TP63 :

-

tumor protein p63 gene

- VEGFA :

-

vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) gene

References

Holgate ST, Wenzel S, Postma DS, Weiss ST, Renz H, Sly PD. Asthma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15025. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.25.

Krämer U, Oppermann H, Ranft U, Schäfer T, Ring J, Behrendt H. Differences in allergy trends between East and West Germany and possible explanations. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:289–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03435.x.

Krämer U, Schmitz R, Ring J, Behrendt H. What can reunification of East and West Germany tell us about the cause of the allergy epidemic? Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:94–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12458.

Renz H, Conrad M, Brand S, Teich R, Garn H, Pfefferle PI. Allergic diseases, gene-environment interactions. Allergy. 2011;66(Suppl 95):10–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02622.x.

Harb H, Alashkar Alhamwe B, Garn H, Renz H, Potaczek DP. Recent developments in epigenetics of pediatric asthma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:754–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000424.

Potaczek DP, Harb H, Michel S, Alaskhar Alhamwe B, Renz H, Tost J. Epigenetics and allergy: from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Epigenomics. 2017;9:539–71. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2016-0162.

Kabesch M. Early origins of asthma (and allergy). Mol Cell Pediatr. 2016;3:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-016-0056-4.

Yang IV, Lozupone CA, Schwartz DA. The environment, epigenome, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.011.

Martino D, Prescott S. Epigenetics and prenatal influences on asthma and allergic airways disease. Chest. 2011;139:640–7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-1800.

Schieck M, Sharma V, Michel S, Toncheva AA, Worth L, Potaczek DP, et al. A polymorphism in the TH 2 locus control region is associated with changes in DNA methylation and gene expression. Allergy. 2014;69:1171–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12450.

Healy S, Khan P, He S, Davie JR. Histone H3 phosphorylation, immediate-early gene expression, and the nucleosomal response: a historical perspective. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90:39–54. https://doi.org/10.1139/o11-092.

Sawicka A, Seiser C. Histone H3 phosphorylation—a versatile chromatin modification for different occasions. Biochimie. 2012;94:2193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.04.018.

Rossetto D, Avvakumov N, Côté J. Histone phosphorylation: a chromatin modification involved in diverse nuclear events. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1098–108. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.21975.

Swygert SG, Peterson CL. Chromatin dynamics: interplay between remodeling enzymes and histone modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:728–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.013.

Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.22.

Gansen A, Tóth K, Schwarz N, Langowski J. Opposing roles of H3- and H4-acetylation in the regulation of nucleosome structure—a FRET study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1433–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1354.

Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression. Cell. 2004;117:721–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.023.

Agricola E, Verdone L, Di Mauro E, Caserta M. H4 acetylation does not replace H3 acetylation in chromatin remodelling and transcription activation of Adr1-dependent genes. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1433–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05451.x.

Morera L, Lübbert M, Jung M. Targeting histone methyltransferases and demethylases in clinical trials for cancer therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-016-0223-4.

Sawicka A, Hartl D, Goiser M, Pusch O, Stocsits RR, Tamir IM, et al. H3S28 phosphorylation is a hallmark of the transcriptional response to cellular stress. Genome Res. 2014;24:1808–20. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.176255.114.

Fierz B, Muir TW. Chromatin as an expansive canvas for chemical biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:417–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.938.

Angiolilli C, Baeten DL, Radstake TR, Reedquist KA. The acetyl code in rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Epigenomics. 2017;9:447–61. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2016-0136.

Wapenaar H, Dekker FJ. Histone acetyltransferases: challenges in targeting bi-substrate enzymes. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-016-0225-2.

Ceccacci E, Minucci S. Inhibition of histone deacetylases in cancer therapy: lessons from leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:605–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.36.

Nagy Z, Tora L. Distinct GCN5/PCAF-containing complexes function as co-activators and are involved in transcription factor and global histone acetylation. Oncogene. 2007;26:5341–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210604.

Cieniewicz AM, Moreland L, Ringel AE, Mackintosh SG, Raman A, Gilbert TM, et al. The bromodomain of Gcn5 regulates site specificity of lysine acetylation on histone H3. Mol Cell Proteom. 2014;13:2896–910. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M114.038174.

Fournier M, Tora L. KAT2-mediated PLK4 acetylation contributes to genomic stability by preserving centrosome number. Mol Cell Oncol. 2017;4:e1270391. https://doi.org/10.1080/23723556.2016.1270391.

Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, Kouzarides T, et al. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell. 2007;131:633–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.039.

Klein BJ, Lalonde M-E, Côté J, Yang X-J, Kutateladze TG. Crosstalk between epigenetic readers regulates the MOZ/MORF HAT complexes. Epigenetics. 2014;9:186–93. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.26792.

Lalonde M-E, Avvakumov N, Glass KC, Joncas F-H, Saksouk N, Holliday M, et al. Exchange of associated factors directs a switch in HBO1 acetyltransferase histone tail specificity. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2009–24. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.223396.113.

McCullough CE, Song S, Shin MH, Johnson FB, Marmorstein R. Structural and functional role of acetyltransferase hMOF K274 autoacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:18190–8. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.736264.

Yuan H, Rossetto D, Mellert H, Dang W, Srinivasan M, Johnson J, et al. MYST protein acetyltransferase activity requires active site lysine autoacetylation. EMBO J. 2012;31:58–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2011.382.

Marmorstein R, Trievel RC. Histone modifying enzymes: structures, mechanisms, and specificities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.07.009.

Sun X-J, Man N, Tan Y, Nimer SD, Wang L. The role of histone acetyltransferases in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Front Oncol. 2015;5:108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00108.

Brook PO, Perry MM, Adcock IM, Durham AL. Epigenome-modifying tools in asthma. Epigenomics. 2015;7:1017–32. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi.15.53.

Hull EE, Montgomery MR, Leyva KJ. HDAC inhibitors as epigenetic regulators of the immune system: impacts on cancer therapy and inflammatory diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:8797206. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8797206.

Lombardi PM, Cole KE, Dowling DP, Christianson DW. Structure, mechanism, and inhibition of histone deacetylases and related metalloenzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:735–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.004.

Kaniskan HÜ, Martini ML, Jin J. Inhibitors of protein methyltransferases and demethylases. Chem Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00801.

Hyun K, Jeon J, Park K, Kim J. Writing, erasing and reading histone lysine methylations. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e324. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.11.

Bennani-Baiti IM. Integration of ERα-PELP1-HER2 signaling by LSD1 (KDM1A/AOF2) offers combinatorial therapeutic opportunities to circumventing hormone resistance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3249.

Fang R, Barbera AJ, Xu Y, Rutenberg M, Leonor T, Bi Q, et al. Human LSD2/KDM1b/AOF1 regulates gene transcription by modulating intragenic H3K4me2 methylation. Mol Cell. 2010;39:222–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.008.

Zippo A, Serafini R, Rocchigiani M, Pennacchini S, Krepelova A, Oliviero S. Histone crosstalk between H3S10ph and H4K16ac generates a histone code that mediates transcription elongation. Cell. 2009;138:1122–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.031.

Edmondson DG, Davie JK, Zhou J, Mirnikjoo B, Tatchell K, Dent SYR. Site-specific loss of acetylation upon phosphorylation of histone H3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29496–502. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M200651200.

Lo WS, Trievel RC, Rojas JR, Duggan L, Hsu JY, Allis CD, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 10 in histone H3 is functionally linked in vitro and in vivo to Gcn5-mediated acetylation at lysine 14. Mol Cell. 2000;5:917–26.

Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2468.

Schwertman P, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:379–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2016.58.

Cao J, Yan Q. Histone ubiquitination and deubiquitination in transcription, DNA damage response, and cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:26. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2012.00026.

Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:653–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.014.

Zhang X, Li B, Rezaeian AH, Xu X, Chou P-C, Jin G, et al. H3 ubiquitination by NEDD4 regulates H3 acetylation and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14799. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14799.

Falkenberg KJ, Johnstone RW. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:673–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4360.

Fujisawa T, Filippakopoulos P. Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their roles in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:246–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2016.143.

Tripathi SK, Lahesmaa R. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of T-helper lineage specification. Immunol Rev. 2014;261:62–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12204.

Suarez-Alvarez B, Rodriguez RM, Fraga MF, López-Larrea C. DNA methylation: a promising landscape for immune system-related diseases. Trends Genet. 2012;28:506–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2012.06.005.

Clifford RL, Patel JK, John AE, Tatler AL, Mazengarb L, Brightling CE, Knox AJ. CXCL8 histone H3 acetylation is dysfunctional in airway smooth muscle in asthma: regulation by BET. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L962–72. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00021.2015.

Perry MM, Durham AL, Austin PJ, Adcock IM, Chung KF. BET bromodomains regulate transforming growth factor-β-induced proliferation and cytokine release in asthmatic airway smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9111–21. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.612671.

Comer BS, Camoretti-Mercado B, Kogut PC, Halayko AJ, Solway J, Gerthoffer WT. Cyclooxygenase-2 and microRNA-155 expression are elevated in asthmatic airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:438–47. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2014-0129OC.

Clifford RL, John AE, Brightling CE, Knox AJ. Abnormal histone methylation is responsible for increased vascular endothelial growth factor 165a secretion from airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. J Immunol. 2012;189:819–31. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1103641.

Coward WR, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Jenkins G, Knox AJ, Pang L. A central role for G9a and EZH2 in the epigenetic silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J. 2014;28:3183–96. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-241760.

Sanders YY, Hagood JS, Liu H, Zhang W, Ambalavanan N, Thannickal VJ. Histone deacetylase inhibition promotes fibroblast apoptosis and ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1448–58. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00095113.

Zhang X, Liu H, Hock T, Thannickal VJ, Sanders YY. Histone deacetylase inhibition downregulates collagen 3A1 in fibrotic lung fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:19605–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141019605.

Liu T, Ullenbruch M, Young Choi Y, Yu H, Ding L, Xaubet A, et al. Telomerase and telomere length in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:260–8. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2012-0514OC.

Cahill KN, Raby BA, Zhou X, Guo F, Thibault D, Baccarelli A, et al. Impaired E prostanoid2 expression and resistance to prostaglandin E2 in nasal polyp fibroblasts from subjects with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2014-0486OC.

Cho JS, Moon YM, Park IH, Um JY, Kang JH, Kim TH, et al. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor on extracellular matrix production in human nasal polyp organ cultures. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:18–23. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3827.

Cho JS, Moon YM, Park IH, Um JY, Moon JH, Park SJ, et al. Epigenetic regulation of myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix production in nasal polyp-derived fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:872–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03931.x.

Yang Y, Wicks J, Haitchi HM, Powell RM, Manuyakorn W, Howarth PH, et al. Regulation of a disintegrin and metalloprotease-33 expression by transforming growth factor-β. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:633–40. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2011-0030OC.

Stefanowicz D, Lee JY, Lee K, Shaheen F, Koo H-K, Booth S, et al. Elevated H3K18 acetylation in airway epithelial cells of asthmatic subjects. Respir Res. 2015;16:95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0254-y.

Zhang Y, Leung DYM, Goleva E. Anti-inflammatory and corticosteroid-enhancing actions of vitamin D in monocytes of patients with steroid-resistant and those with steroid-sensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1744.e1–1752.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.004.

Borriello F, Longo M, Spinelli R, Pecoraro A, Granata F, Staiano RI, et al. IL-3 synergises with basophil-derived IL-4 and IL-13 to promote the alternative activation of human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2042–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201445303.

Marwick JA, Tudor C, Khorasani N, Michaeloudes C, Bhavsar PK, Chung KF. Oxidants induce a corticosteroid-insensitive phosphorylation of histone 3 at serine 10 in monocytes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124961. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124961.

Castellucci M, Rossato M, Calzetti F, Tamassia N, Zeminian S, Cassatella MA, Bazzoni F. IL-10 disrupts the Brd4-docking sites to inhibit LPS-induced CXCL8 and TNF-α expression in monocytes: implications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(781–791):e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.023.

Hsieh CC, Kuo CH, Kuo HF, Chen YS, Wang SL, Chao D, et al. Sesamin suppresses macrophage-derived chemokine expression in human monocytes via epigenetic regulation. Food Funct. 2014;5:2494–500. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4fo00322e.

Harb H, Raedler D, Ballenberger N, Böck A, Kesper DA, Renz H, Schaub B. Childhood allergic asthma is associated with increased IL-13 and FOXP3 histone acetylation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:200–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.027.

Seumois G, Chavez L, Gerasimova A, Lienhard M, Omran N, Kalinke L, et al. Epigenomic analysis of primary human T cells reveals enhancers associated with TH2 memory cell differentiation and asthma susceptibility. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:777–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2937.

Huber JP, Gonzales-van Horn SR, Roybal KT, Gill MA, Farrar JD. IFN-α suppresses GATA3 transcription from a distal exon and promotes H3K27 trimethylation of the CNS-1 enhancer in human Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:5687–94. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1301908.

Gerasimova A, Chavez L, Li B, Seumois G, Greenbaum J, Rao A, et al. Predicting cell types and genetic variations contributing to disease by combining GWAS and epigenetic data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054359.

C-y Li, Peng J, L-p Ren, Gan L-x Lu, X-j Liu Q, et al. Roles of histone hypoacetylation in LAT expression on T cells and Th2 polarization in allergic asthma. J Transl Med. 2013;11:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-11-26.

Luo S, Liang G, Zhang P, Zhao M, Lu Q. Aberrant histone modifications in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Clin Immunol. 2013;146:165–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2012.12.009.

Han J, Park S-G, Bae J-B, Choi J, Lyu J-M, Park SH, et al. The characteristics of genome-wide DNA methylation in naïve CD4+ T cells of patients with psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:157–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.128.

Dunstan JA, West C, McCarthy S, Metcalfe J, Meldrum S, Oddy WH, et al. The relationship between maternal folate status in pregnancy, cord blood folate levels, and allergic outcomes in early childhood. Allergy. 2012;67:50–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02714.x.

McStay CL, Prescott SL, Bower C, Palmer DJ. Maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and childhood allergic disease outcomes: a question of timing? Nutrients. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020123.

D’Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA, Lee-Pullen TF, Metcalfe J, Holt BJ, et al. Fish oil supplementation in early infancy modulates developing infant immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1206–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04031.x.

Dunstan JA, Mori TA, Barden A, Beilin LJ, Taylor AL, Holt PG, Prescott SL. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal allergen-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes in infants at high risk of atopy: a randomized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1178–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.009.

Harb H, Amarasekera M, Ashley S, Tulic MK, Pfefferle PI, Potaczek DP, et al. Epigenetic regulation in early childhood: a miniaturized and validated method to assess histone acetylation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;168:173–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442158.

Harb H, Irvine J, Amarasekera M, Hii CS, Kesper DA, Ma Y, et al. The role of PKCζ in cord blood T-cell maturation towards Th1 cytokine profile and its epigenetic regulation by fish oil. Biosci Rep. 2017;37:BSR20160485. https://doi.org/10.1042/bsr20160485.

Kobayashi Y, Bossley C, Gupta A, Akashi K, Tsartsali L, Mercado N, et al. Passive smoking impairs histone deacetylase-2 in children with severe asthma. Chest. 2014;145:305–12. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0835.

Kabesch M, Adcock IM. Epigenetics in asthma and COPD. Biochimie. 2012;94:2231–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.07.017.

Kidd CDA, Thompson PJ, Barrett L, Baltic S. Histone modifications and asthma. the interface of the epigenetic and genetic landscapes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0050TR.

Liu R, Leslie KL, Martin KA. Epigenetic regulation of smooth muscle cell plasticity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:448–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.004.

Royce SG, Ververis K, Karagiannis TC. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: can we consider potent anti-neoplastic agents for the treatment of asthma? Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2012;42:338–45.

Salam MT. Asthma epigenetics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;795:183–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8603-9_11.

Tost J, Gay S, Firestein G. Epigenetics of the immune system and alterations in inflammation and autoimmunity. Epigenomics. 2017;9:371–3. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2017-0026.

Tost J. Engineering of the epigenome: synthetic biology to define functional causality and develop innovative therapies. Epigenomics. 2016;8:153–6. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi.15.112.

Potaczek DP, Garn H, Unger SD, Renz H. Antisense molecules: a new class of drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1334–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1344.

Garn H, Renz H. GATA-3-specific DNAzyme—a novel approach for stratified asthma therapy. Eur J Immunol. 2017;47:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201646450.

Krug N, Hohlfeld JM, Kirsten A-M, Kornmann O, Beeh KM, Kappeler D, et al. Allergen-induced asthmatic responses modified by a GATA3-specific DNAzyme. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1987–95. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411776.

Chen CH, Wang CZ, Wang YH, Liao WT, Chen YJ, Kuo CH, et al. Effects of low-level laser therapy on M1-related cytokine expression in monocytes via histone modification. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:625048. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/625048.

Nestor CE, Barrenäs F, Wang H, Lentini A, Zhang H, Bruhn S, et al. DNA methylation changes separate allergic patients from healthy controls and may reflect altered CD4+ T-cell population structure. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004059. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004059.

Martino D, Joo JE, Sexton-Oates A, Dang T, Allen K, Saffery R, Prescott S. Epigenome-wide association study reveals longitudinally stable DNA methylation differences in CD4+ T cells from children with IgE-mediated food allergy. Epigenetics. 2014;9:998–1006. https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.28945.

Martino D, Dang T, Sexton-Oates A, Prescott S, Tang MLK, Dharmage S, et al. Blood DNA methylation biomarkers predict clinical reactivity in food-sensitized infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1319.e1-12–1328.e1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1933.

Cell signaling technology. Histone modification table. https://www.cellsignal.com/contents/resources-reference-tables/histone-modification-table/science-tables-histone. Accessed 21 July 2017.

Kuo CH, Lin CH, Yang SN, Huang MY, Chen HL, Kuo PL, et al. Effect of prostaglandin I2 analogs on cytokine expression in human myeloid dendritic cells via epigenetic regulation. Mol Med. 2012;18:433–44. https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2011.00193.

Zhong F, Zhou N, Wu K, Guo Y, Tan W, Zhang H, et al. A SnoRNA-derived piRNA interacts with human interleukin-4 pre-mRNA and induces its decay in nuclear exosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10474–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv954.

Zheng J, van de Veerdonk FL, Crossland KL, Smeekens SP, Chan CM, Al Shehri T, et al. Gain-of-function STAT1 mutations impair STAT3 activity in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2834–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201445344.

Vicente CT, Edwards SL, Hillman KM, Kaufmann S, Mitchell H, Bain L, et al. Long-range modulation of PAG1 expression by 8q21 allergy risk variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:329–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.010.

Naranbhai V, Fairfax BP, Makino S, Humburg P, Wong D, Ng E, et al. Genomic modulators of gene expression in human neutrophils. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7545. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8545.

Lin CC, Lin WN, Hou WC, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. Endothelin-1 induces VCAM-1 expression-mediated inflammation via receptor tyrosine kinases and Elk/p300 in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L211–25. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00232.2014.

Sharma S, Zhou X, Thibault DM, Himes BE, Liu A, Szefler SJ, et al. A genome-wide survey of CD4(+) lymphocyte regulatory genetic variants identifies novel asthma genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1153–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.011.

Escobar TM, Kanellopoulou C, Kugler DG, Kilaru G, Nguyen CK, Nagarajan V, et al. miR-155 activates cytokine gene expression in Th17 cells by regulating the DNA-binding protein Jarid2 to relieve polycomb-mediated repression. Immunity. 2014;40:865–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.014.

Gschwandtner M, Zhong S, Tschachler A, Mlitz V, Karner S, Elbe-Bürger A, Mildner M. Fetal human keratinocytes produce large amounts of antimicrobial peptides: involvement of histone-methylation processes. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2192–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.165.

Han H, Xu D, Liu C, Claesson H-E, Björkholm M, Sjöberg J. Interleukin-4-mediated 15-lipoxygenase-1 trans-activation requires UTX recruitment and H3K27me3 demethylation at the promoter in A549 cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085085.

Lakshmi SP, Reddy AT, Zhang Y, Sciurba FC, Mallampalli RK, Duncan SR, Reddy RC. Down-regulated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in lung epithelial cells promotes a PPARγ agonist-reversible proinflammatory phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6383–93. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.536805.

Wiegman CH, Li F, Clarke CJ, Jazrawi E, Kirkham P, Barnes PJ, et al. A comprehensive analysis of oxidative stress in the ozone-induced lung inflammation mouse model. Clin Sci. 2014;126:425–40. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20130039.

Che W, Parmentier J, Seidel P, Manetsch M, Ramsay EE, Alkhouri H, et al. Corticosteroids inhibit sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced interleukin-6 secretion from human airway smooth muscle via mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1-mediated repression of mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase 1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:358–68. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2013-0208OC.

Kallsen K, Andresen E, Heine H. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1 controls the expression of beta defensin 1 in human lung epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050000.

Robertson ED, Weir L, Romanowska M, Leigh IM, Panteleyev AA. ARNT controls the expression of epidermal differentiation genes through HDAC- and EGFR-dependent pathways. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3320–32. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.095125.

Vazquez BN, Laguna T, Notario L, Lauzurica P. Evidence for an intronic cis-regulatory element within CD69 gene. Genes Immun. 2012;13:356–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/gene.2012.4.

Zijlstra GJ, ten Hacken NHT, Hoffmann RF, van Oosterhout AJM, Heijink IH. Interleukin-17A induces glucocorticoid insensitivity in human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:439–45. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00017911.

Authors’ contributions

BAA, RK, and JW drafted the first version of the manuscript. VvB, HH, FA, CSH, and SLP contributed to the specific parts of the first draft. DPP, HG, BAA, and HR developed the design of this work. DPP and RK conducted the systematic search. DPP, HG, AF, and HR wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final mansucript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mrs. Inge Schmidt and Mrs. Jorun Braun for their secretarial assistance.

For Abbreviations used in plain text, please refer to “Abbreviations” section; for histone modification code, please, refer to Table 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data is sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current work.

Consent for publication

All authors provided consent for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (review article with no original data reported)

Funding

This work was supported by the German Center for Lung Research (DZL; 82DZL00502/A2), the Universities Giessen and Marburg Lung Centre (UGMLC), the Von Behring-Röntgen-Foundation (Von Behring-Röntgen-Stiftung), and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (Grant Numbers: 353555, 513709). BAA is the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) fellow (personal reference number: 91559386). FA is supported by HessenFonds, World University Service (WUS), the Hessen State Ministry for Higher Education, Research and the Arts (HMWK).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Alaskhar Alhamwe, B., Khalaila, R., Wolf, J. et al. Histone modifications and their role in epigenetics of atopy and allergic diseases. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 14, 39 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0259-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0259-4